-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yeela Talmor-Barkan, Nancy-Sarah Yacovzada, Hagai Rossman, Guy Witberg, Iris Kalka, Ran Kornowski, Eran Segal, Head-to-head efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran in an observational nationwide targeted trial, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy, Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 26–37, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvac063

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

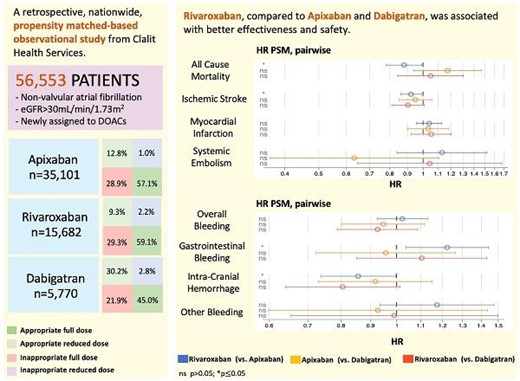

The advantages of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) over warfarin are well established in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients, however, studies that can guide the selection between different DOACs are limited. The aim was to compare the clinical outcomes of treatment with apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran in patients with AF.

We conducted a retrospective, nationwide, propensity score-matched-based observational study from Clalit Health Services. Data from 141 992 individuals with AF was used to emulate a target trial for head-to-head comparison of DOACs therapy. Three-matched cohorts of patients assigned to DOACs, from January-2014 through January-2020, were created. One-to-one propensity score matching was performed. Efficacy/safety outcomes were compared using KaplanMeier survival estimates and Cox proportional hazards models. The trial included 56 553 patients (apixaban, n = 35 101; rivaroxaban, n = 15 682; dabigatran, n = 5 770). Mortality and ischaemic stroke rates in patients treated with rivaroxaban were lower compared with apixaban (HR,0.88; 95% CI,0.78–0.99; P,0.037 and HR 0.92; 95% CI,0.86–0.99; P,0.024, respectively). No significant differences in the rates of myocardial infarction, systemic embolism, and overall bleeding were noticed between the different DOACs groups. Patients treated with rivaroxaban demonstrated lower rate of intracranial haemorrhage compared with apixaban (HR,0.86; 95% CI,0.74–1.0; P,0.044). The rate of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with rivaroxaban was higher compared with apixaban (HR, 1.22; 95% CI,1.01–1.44; P, 0.016).

We demonstrated significant differences in outcomes between the three studied DOACs. The results emphasize the need for randomized controlled trials that will compare rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran in order to better guide the selection among them.

Six-years follow-up of 56,553 patients who were treated with apixaban, rivaroxaban or dabigatran for non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

Key questions

What are the differences in efficacy and safety outcomes between rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran?

Key findings

Treatment with rivaroxaban was associated with decreased rates of all-cause mortality, ischaemic stroke, and intracranial bleeding compared with apixaban.

Rivaroxaban compared with dabigatran demonstrated decreased rate of all-cause mortality and ischaemic stroke in patients under the age of 70 years, and decreased rate of intracranial haemorrhage in patients aged 80 years or above.

Rivaroxaban was associated with increased gastrointestinal bleeding compared with apixaban.

Take-home message

The differences in efficacy and safety outcomes between rivaroxaban, apixaban and dabigatran warrant further randomized controlled trials.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common heart arrhythmia that is associated with an increased risk of mortality and embolic events, mainly stroke.1 The prevention of stroke in patients with AF is obtained by anticoagulant treatment.2 Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have several advantages over warfarin including fewer drug interactions, more predictable pharmacological profiles, and an absence of major dietary effects. In addition, data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that DOACs were non-inferior to warfarin with respect to the risk of thromboembolic and bleeding events in AF patients.3–5 Therefore, treatment with DOACs has become widespread in clinical practice.6–8

Currently, there are limited data to guide the selection between rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran. To date, the comparison between the different DOACs for the treatment of AF was not examined under RCTs and the data is based on retrospective analysis from different cohorts.7–11 The majority of studies demonstrate similar efficacy and safety among agents. For example, in a nationwide cohort of patients with AF from Denmark, no overall statistically significant differences were observed in stroke, systemic embolism or major bleeding in apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran.12 Additionally, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran appear to have similar effectiveness, although apixaban may be associated with lower bleeding risk and rivaroxaban may be associated with elevated bleeding risk.13 A recent study from Iceland showed that rivaroxaban was associated with higher gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding rates than apixaban and dabigatran regardless of treatment indication.14

Larger and more representative observational data sets with longer follow-up may add important information to guide the selection between the different DOACs in patients suffering from AF. Therefore, by using observational data from the largest Health Care Organization (HCO) in Israel, we designed a target trial15,16 and then emulated its protocol to compare the effectiveness and safety between apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran in patients with AF.

Methods

Data source

The study was based on the database of Clalit Health Services (CHS), the largest HCO in Israel, encompassing over 19 years of full administrative and clinical data. This health care system provides care for 4.7 million patients, with a membership that is approximately representative of the Israeli population with respect to both socioeconomic status and prevalence of coexisting diseases.17 The database that we used in this study has been described previously.18 Medical records include International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes, and ICD-9 procedure codes. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Clalit Health Services approval number 0195–17-COM2, and by the Ethics Committee of Rabin Medical Center, approval number 0096–20-RMC. Since the study was based on retrospective data, it was exempt from the provision of patients’ written informed consent.

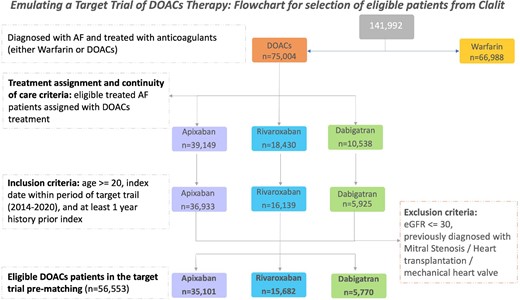

Study design

An observational study was designed to emulate a target trial of the effect of different DOACs treatment on the outcomes of patients with AF.15,16,19 Participant's time zero is determined when the participants meet the eligibility criteria and are assigned to a treatment strategy (as enforced in randomized trials). Eligibility criteria included individuals between the age of 20 and 100 years, with a diagnosis of AF that issued a prescription for apixaban, rivaroxaban or dabigatran from 1 January 2014 to 1 January 2020, and being a member of the HCO during the previous 12 months. Additionally, only patients fulfilling the continuity of care criteria were eligible in the study (see online methods; Study Exposures). Exclusion criteria included previous heart transplantation, mitral stenosis, mechanical valve, and renal failure with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or below.

Follow-up started at first eligible DOACs prescription and ended at an outcome event including death, treatment discontinuation, disenrollment from Clalit HCO, end of follow-up (6 years after index event), or the end of the study (May 1, 2020), whichever occurs first. All DOACs recipients were matched in a 1:1 ratio for the following variables: age, sex, creatinine, eGFR, haemoglobin (Hb), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), c A1C (HbA1C), CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores, hypertension, previous overall bleeding, previous ischaemic stroke, previous myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery disease (CAD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), diabetes mellitus (DM), congestive heart failure (CHF), previous venous thromboembolism (VTE), cirrhosis and use of antiplatelet drugs (aspirin/plavix/effient/brilinta). Dabigatran was the first DOAC to be introduced into clinical practice in Israel followed by rivaroxaban, and apixaban. Edoxaban is not marked in Israel and therefore, was not included in the study. Therefore, treatment assignment was identified by index prescription only after January 2014, when the use of all three drugs was available (Supplementary eFigure 20). The target trial emulation protocol is described in Supplementary eTable 1, as accepted in other observational emulation frameworks.20

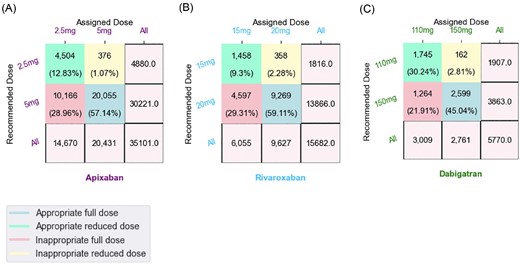

DOACs dosage

AF treatment guidelines recommend using the lower dose of DOACs in certain clinical conditions.8 For apixaban, a low dose is recommended for patients with at least 2 of the following characteristics: age ≥80 years, body weight ≤60 kg or serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL. For rivaroxaban low dose is recommended for patients with eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m2. For dabigatran, a low dose is recommended for patients with at least 1 of the following characteristics: age > 80 years, concomitant treatment with verapamil, or eGFR 15-30 mL/min/1.73m2.8,21–23 Patients prescribed 20 mg of rivaroxaban, 5 mg of apixaban bid, or 150 mg of dabigatran bid were considered to be receiving a standard dose; Rivaroxaban 15 mg, apixaban 2.5 mg bid and dabigatran 110 mg bid were considered as reduced doses. We considered patients as receiving an appropriate dose when they received the recommended dose according to current guidelines. We considered patients as receiving inappropriate low doses while according to current guidelines they should have received a full dose, but in practice, they received a low dose. Finally, we considered patients as receiving an inappropriate full dose when patients should have received a low dose but in practice received a full dose (see Supplementary material).

Evaluated outcomes

The efficacy outcomes were mortality, ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or systemic embolism. The safety outcomes were gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, intracranial haemorrhage (ICH), bleeding from other sites, and overall bleeding (GI bleeding, ICH, and bleeding from other sites). Regarding ICH, we included bleeding events that were not triggered by trauma or by ischaemic stroke, to exclude haemorrhagic transformation of ischaemic stroke. The ICD-9 codes used are listed in Supplementary eTable 3 (see Supplementary material).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed two sensitivity analyses: (1) According to 3 different age groups (<70 years, 7080 years, 80 years and above), (Supplementary eFigures 4–10); (2) according to renal function (eGFR between 30 to 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, eGFR|$\ge $|50 mL/min/1.73 m2), (Supplementary eFigures 11–17).

Negative controls

The validity of the observational associations and detection of unmeasured confounding was examined by a falsification hypothesis (negative control) by using the same observational matched cohorts and replicating the analytic approach. The prerequisite to proper falsification analyses was satisfied by identifying a hypothesis that tests a putative mechanism of potential bias.24 Propensity Score Matching (PSM) based cohorts were tested for a potential mechanism of confounding, by running the analysis on a herpes zoster outcome (Supplementary eFigure 3), a relatively common diagnosis in adults unrelated to DOACs treatment, providing additional confidence that selection bias is not reflected among DOACs groups.

Statistical analysis

Study cohorts were generated following a PSM strategy (see online methods). The matched covariate distributions across each pair of treatment groups are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary eFigure 19. KaplanMeier survival analysis of the three comparator DOACs cohorts was used to estimate the cumulative survival and time-to-event curves. Significance of the difference between survival functions was assessed using a log-rank test. We estimate the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) on several cardiac morbidities and mortality. Cox Proportional Hazards models were used to compare the outcome event risk of the comparator DOACs in each of the three matched cohorts. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each outcome of interest were calculated. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Baseline Characteristics of 1:1 Propensity Score-based Matched Cohorts (a) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (b) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (c) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban

| . | Apixaban (n = 15 668) . | Rivaroxaban (n = 15 668) . | SMD . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban . | |||

| Age, yrs | 76.2 (9.6) | 76.2 (9.6) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 7 547 (48.2%) | 7 523 (48.0%) | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.8 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | −0.017 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.0 (1.7) | 13.0 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (14.4) | 23.5 (12.8) | 0.022 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.1 (20.0) | 20.4 (15.7) | 0.039 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.5 (39.7) | 84.5 (41.6) | 0.025 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.9 (76.9) | 228.6 (73.4) | 0.017 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 90.3 (31.6) | 90.8 (30.7) | −0.016 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 76.3 (23.1) | 76.2 (23.2) | 0.004 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 4.1 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 7 537 (48.1%) | 7 521 (48.0%) | 0.002 |

| Previous hypertension (%) | 14 067 (89.8%) | 14 005 (89.4%) | 0.013 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 1 508 (9.6%) | 1 517 (9.7%) | −0.003 |

| Previous GI-bleeding (%) | 581 (3.7%) | 567 (3.6%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 723 (4.6%) | 700 (4.5%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 273 (1.7%) | 317 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 2 546 (16.2%) | 2 539 (16.2%) | 0 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 2 698 (17.2%) | 2 559 (16.3%) | 0.024 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 1 193 (7.6%) | 1 163 (7.4%) | 0.008 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 93 (0.6%) | 52 (0.3%) | 0.045 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 442 (2.8%) | 303 (1.9%) | 0.059 |

| CHF (%) | 4 701 (30.0%) | 4 768 (30.4%) | −0.009 |

| PAD (%) | 2 509 (16.0%) | 2 399 (15.3%) | 0.019 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 127 (0.8%) | 123 (0.8%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 822 (5.2%) | 867 (5.5%) | −0.013 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 94 (0.6%) | 97 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 6 509 (41.5%) | 8 127 (51.9%) | −0.21 |

| Statins use (%) | 13 367 (85.3%) | 13 234 (84.5%) | 0.022 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 0 |

| PPIs use (%) | 12 386 (79.1%) | 12 223 (78.0%) | 0.027 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 7 757 (49.5%) | 8 144 (52.0%) | −0.05 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 4 430 (28.3%) | 4 451 (28.4%) | −0.002 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 10 165 (0.6%) | 9256 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1406 (0.1%) | 1458 (0.1%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 142 (0.0%) | 358 (0.0%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 3955 (0.3%) | 4596 (0.3%) | 0 |

| Apixaban (n = 5 767) | Dabigatran (n = 5 767) | SMD | |

| (b) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban | |||

| Age, yrs | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 887 (50.1%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (6.0) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.7) | 13.1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.9 (12.1) | 23.8 (11.7) | 0.008 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.6 (19.2) | 21.5 (22.9) | 0.005 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.4 (39.7) | 83.9 (35.6) | 0.04 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 231.9 (79.7) | 229.0 (72.5) | 0.038 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.4 (31.9) | 89.6 (30.9) | −0.006 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.0) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.1 (22.3) | 79.3 (22.9) | −0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 721 (47.2%) | 2 659 (46.1%) | 0.022 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 049 (87.5%) | 5 018 (87.0%) | 0.015 |

| Previous Total-Bleeding (%) | 590 (10.2%) | 602 (10.4%) | −0.007 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 218 (3.8%) | 225 (3.9%) | −0.005 |

| Previous Bleeding-ICH (%) | 287 (5.0%) | 301 (5.2%) | −0.009 |

| Previous Bleeding-Other (%) | 115 (2.0%) | 99 (1.7%) | 0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 0.008 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 075 (18.6%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 0.026 |

| Previous Stroke (%) | 512 (8.9%) | 535 (9.3%) | −0.014 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 28 (0.5%) | 27 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 157 (2.7%) | 131 (2.3%) | 0.026 |

| CHF (%) | 1 591 (27.6%) | 1 549 (26.9%) | 0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 851 (14.8%) | 805 (14.0%) | 0.023 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 43 (0.7%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 176 (3.1%) | 190 (3.3%) | −0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 49 (0.8%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 308 (40.0%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | −0.176 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 959 (86.0%) | 4 921 (85.3%) | 0.02 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 458 (94.6%) | 5 446 (94.4%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 534 (78.6%) | 4 481 (77.7%) | 0.022 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 825 (49.0%) | 2 689 (46.6%) | 0.048 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 789 (31.0%) | 1 739 (30.2%) | 0.017 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 4097 (0.7%) | 2597 (0.5%) | 0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 381 (0.1%) | 1745 (0.3%) | −0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 47 (0.0%) | 162 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1242 (0.2%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 0 |

| Dabigatran (n = 5 766) | Rivaroxaban (n = 5 766) | SMD | |

| (c) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban | |||

| Age, years | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | 2 946 (51.1%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.6) | 13.1 (1.7) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (11.7) | 23.5 (9.9) | 0.028 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.3 (14.7) | 21.0 (14.0) | 0.021 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 83.9 (35.7) | 84.0 (35.6) | −0.003 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.0 (72.5) | 228.3 (72.9) | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.6 (30.9) | 90.7 (30.6) | −0.036 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.3 (22.9) | 79.1 (22.2) | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.6) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 657 (46.1%) | 2 663 (46.2%) | −0.002 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 016 (87.0%) | 5 038 (87.4%) | −0.012 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 602 (10.4%) | 595 (10.3%) | 0.003 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 225 (3.9%) | 213 (3.7%) | 0.01 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 301 (5.2%) | 292 (5.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 99 (1.7%) | 116 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 987 (17.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 013 (17.6%) | 957 (16.6%) | 0.027 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 535 (9.3%) | 536 (9.3%) | 0 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 27 (0.5%) | 19 (0.3%) | 0.032 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 131 (2.3%) | 110 (1.9%) | 0.028 |

| CHF (%) | 1 548 (26.8%) | 1 585 (27.5%) | −0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 805 (14.0%) | 841 (14.6%) | −0.017 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 40 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 189 (3.3%) | 177 (3.1%) | 0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 48 (0.8%) | −0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | 2 921 (50.7%) | −0.04 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 919 (85.3%) | 4 849 (84.1%) | 0.033 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 445 (94.4%) | 5 434 (94.2%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 479 (77.7%) | 4 496 (78.0%) | −0.007 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 688 (46.6%) | 2 907 (50.4%) | −0.076 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 738 (30.1%) | 1 693 (29.4%) | 0.015 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 2596 (0.5%) | 3791 (0.7%) | −0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1745 (0.3%) | 360 (0.1%) | 0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 162 (0.0%) | 88 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 1527 (0.3%) | −0.232 |

| . | Apixaban (n = 15 668) . | Rivaroxaban (n = 15 668) . | SMD . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban . | |||

| Age, yrs | 76.2 (9.6) | 76.2 (9.6) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 7 547 (48.2%) | 7 523 (48.0%) | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.8 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | −0.017 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.0 (1.7) | 13.0 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (14.4) | 23.5 (12.8) | 0.022 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.1 (20.0) | 20.4 (15.7) | 0.039 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.5 (39.7) | 84.5 (41.6) | 0.025 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.9 (76.9) | 228.6 (73.4) | 0.017 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 90.3 (31.6) | 90.8 (30.7) | −0.016 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 76.3 (23.1) | 76.2 (23.2) | 0.004 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 4.1 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 7 537 (48.1%) | 7 521 (48.0%) | 0.002 |

| Previous hypertension (%) | 14 067 (89.8%) | 14 005 (89.4%) | 0.013 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 1 508 (9.6%) | 1 517 (9.7%) | −0.003 |

| Previous GI-bleeding (%) | 581 (3.7%) | 567 (3.6%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 723 (4.6%) | 700 (4.5%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 273 (1.7%) | 317 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 2 546 (16.2%) | 2 539 (16.2%) | 0 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 2 698 (17.2%) | 2 559 (16.3%) | 0.024 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 1 193 (7.6%) | 1 163 (7.4%) | 0.008 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 93 (0.6%) | 52 (0.3%) | 0.045 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 442 (2.8%) | 303 (1.9%) | 0.059 |

| CHF (%) | 4 701 (30.0%) | 4 768 (30.4%) | −0.009 |

| PAD (%) | 2 509 (16.0%) | 2 399 (15.3%) | 0.019 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 127 (0.8%) | 123 (0.8%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 822 (5.2%) | 867 (5.5%) | −0.013 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 94 (0.6%) | 97 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 6 509 (41.5%) | 8 127 (51.9%) | −0.21 |

| Statins use (%) | 13 367 (85.3%) | 13 234 (84.5%) | 0.022 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 0 |

| PPIs use (%) | 12 386 (79.1%) | 12 223 (78.0%) | 0.027 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 7 757 (49.5%) | 8 144 (52.0%) | −0.05 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 4 430 (28.3%) | 4 451 (28.4%) | −0.002 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 10 165 (0.6%) | 9256 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1406 (0.1%) | 1458 (0.1%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 142 (0.0%) | 358 (0.0%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 3955 (0.3%) | 4596 (0.3%) | 0 |

| Apixaban (n = 5 767) | Dabigatran (n = 5 767) | SMD | |

| (b) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban | |||

| Age, yrs | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 887 (50.1%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (6.0) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.7) | 13.1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.9 (12.1) | 23.8 (11.7) | 0.008 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.6 (19.2) | 21.5 (22.9) | 0.005 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.4 (39.7) | 83.9 (35.6) | 0.04 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 231.9 (79.7) | 229.0 (72.5) | 0.038 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.4 (31.9) | 89.6 (30.9) | −0.006 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.0) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.1 (22.3) | 79.3 (22.9) | −0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 721 (47.2%) | 2 659 (46.1%) | 0.022 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 049 (87.5%) | 5 018 (87.0%) | 0.015 |

| Previous Total-Bleeding (%) | 590 (10.2%) | 602 (10.4%) | −0.007 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 218 (3.8%) | 225 (3.9%) | −0.005 |

| Previous Bleeding-ICH (%) | 287 (5.0%) | 301 (5.2%) | −0.009 |

| Previous Bleeding-Other (%) | 115 (2.0%) | 99 (1.7%) | 0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 0.008 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 075 (18.6%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 0.026 |

| Previous Stroke (%) | 512 (8.9%) | 535 (9.3%) | −0.014 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 28 (0.5%) | 27 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 157 (2.7%) | 131 (2.3%) | 0.026 |

| CHF (%) | 1 591 (27.6%) | 1 549 (26.9%) | 0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 851 (14.8%) | 805 (14.0%) | 0.023 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 43 (0.7%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 176 (3.1%) | 190 (3.3%) | −0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 49 (0.8%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 308 (40.0%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | −0.176 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 959 (86.0%) | 4 921 (85.3%) | 0.02 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 458 (94.6%) | 5 446 (94.4%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 534 (78.6%) | 4 481 (77.7%) | 0.022 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 825 (49.0%) | 2 689 (46.6%) | 0.048 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 789 (31.0%) | 1 739 (30.2%) | 0.017 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 4097 (0.7%) | 2597 (0.5%) | 0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 381 (0.1%) | 1745 (0.3%) | −0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 47 (0.0%) | 162 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1242 (0.2%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 0 |

| Dabigatran (n = 5 766) | Rivaroxaban (n = 5 766) | SMD | |

| (c) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban | |||

| Age, years | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | 2 946 (51.1%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.6) | 13.1 (1.7) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (11.7) | 23.5 (9.9) | 0.028 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.3 (14.7) | 21.0 (14.0) | 0.021 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 83.9 (35.7) | 84.0 (35.6) | −0.003 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.0 (72.5) | 228.3 (72.9) | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.6 (30.9) | 90.7 (30.6) | −0.036 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.3 (22.9) | 79.1 (22.2) | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.6) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 657 (46.1%) | 2 663 (46.2%) | −0.002 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 016 (87.0%) | 5 038 (87.4%) | −0.012 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 602 (10.4%) | 595 (10.3%) | 0.003 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 225 (3.9%) | 213 (3.7%) | 0.01 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 301 (5.2%) | 292 (5.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 99 (1.7%) | 116 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 987 (17.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 013 (17.6%) | 957 (16.6%) | 0.027 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 535 (9.3%) | 536 (9.3%) | 0 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 27 (0.5%) | 19 (0.3%) | 0.032 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 131 (2.3%) | 110 (1.9%) | 0.028 |

| CHF (%) | 1 548 (26.8%) | 1 585 (27.5%) | −0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 805 (14.0%) | 841 (14.6%) | −0.017 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 40 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 189 (3.3%) | 177 (3.1%) | 0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 48 (0.8%) | −0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | 2 921 (50.7%) | −0.04 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 919 (85.3%) | 4 849 (84.1%) | 0.033 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 445 (94.4%) | 5 434 (94.2%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 479 (77.7%) | 4 496 (78.0%) | −0.007 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 688 (46.6%) | 2 907 (50.4%) | −0.076 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 738 (30.1%) | 1 693 (29.4%) | 0.015 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 2596 (0.5%) | 3791 (0.7%) | −0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1745 (0.3%) | 360 (0.1%) | 0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 162 (0.0%) | 88 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 1527 (0.3%) | −0.232 |

Values are mean (±SD) or n (%). BMI, body mass index; Hb, haemoglobin; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PLTs, platelets; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GI, gastrointestinal; ICH, intra cranial haemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; CHF, congestive heart failure; PAD, peripheral artery disease; VTE, venous thromboembolism; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPIs, proton-pump inhibitors.

Baseline Characteristics of 1:1 Propensity Score-based Matched Cohorts (a) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (b) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (c) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban

| . | Apixaban (n = 15 668) . | Rivaroxaban (n = 15 668) . | SMD . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban . | |||

| Age, yrs | 76.2 (9.6) | 76.2 (9.6) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 7 547 (48.2%) | 7 523 (48.0%) | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.8 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | −0.017 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.0 (1.7) | 13.0 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (14.4) | 23.5 (12.8) | 0.022 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.1 (20.0) | 20.4 (15.7) | 0.039 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.5 (39.7) | 84.5 (41.6) | 0.025 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.9 (76.9) | 228.6 (73.4) | 0.017 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 90.3 (31.6) | 90.8 (30.7) | −0.016 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 76.3 (23.1) | 76.2 (23.2) | 0.004 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 4.1 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 7 537 (48.1%) | 7 521 (48.0%) | 0.002 |

| Previous hypertension (%) | 14 067 (89.8%) | 14 005 (89.4%) | 0.013 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 1 508 (9.6%) | 1 517 (9.7%) | −0.003 |

| Previous GI-bleeding (%) | 581 (3.7%) | 567 (3.6%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 723 (4.6%) | 700 (4.5%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 273 (1.7%) | 317 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 2 546 (16.2%) | 2 539 (16.2%) | 0 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 2 698 (17.2%) | 2 559 (16.3%) | 0.024 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 1 193 (7.6%) | 1 163 (7.4%) | 0.008 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 93 (0.6%) | 52 (0.3%) | 0.045 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 442 (2.8%) | 303 (1.9%) | 0.059 |

| CHF (%) | 4 701 (30.0%) | 4 768 (30.4%) | −0.009 |

| PAD (%) | 2 509 (16.0%) | 2 399 (15.3%) | 0.019 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 127 (0.8%) | 123 (0.8%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 822 (5.2%) | 867 (5.5%) | −0.013 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 94 (0.6%) | 97 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 6 509 (41.5%) | 8 127 (51.9%) | −0.21 |

| Statins use (%) | 13 367 (85.3%) | 13 234 (84.5%) | 0.022 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 0 |

| PPIs use (%) | 12 386 (79.1%) | 12 223 (78.0%) | 0.027 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 7 757 (49.5%) | 8 144 (52.0%) | −0.05 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 4 430 (28.3%) | 4 451 (28.4%) | −0.002 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 10 165 (0.6%) | 9256 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1406 (0.1%) | 1458 (0.1%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 142 (0.0%) | 358 (0.0%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 3955 (0.3%) | 4596 (0.3%) | 0 |

| Apixaban (n = 5 767) | Dabigatran (n = 5 767) | SMD | |

| (b) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban | |||

| Age, yrs | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 887 (50.1%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (6.0) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.7) | 13.1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.9 (12.1) | 23.8 (11.7) | 0.008 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.6 (19.2) | 21.5 (22.9) | 0.005 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.4 (39.7) | 83.9 (35.6) | 0.04 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 231.9 (79.7) | 229.0 (72.5) | 0.038 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.4 (31.9) | 89.6 (30.9) | −0.006 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.0) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.1 (22.3) | 79.3 (22.9) | −0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 721 (47.2%) | 2 659 (46.1%) | 0.022 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 049 (87.5%) | 5 018 (87.0%) | 0.015 |

| Previous Total-Bleeding (%) | 590 (10.2%) | 602 (10.4%) | −0.007 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 218 (3.8%) | 225 (3.9%) | −0.005 |

| Previous Bleeding-ICH (%) | 287 (5.0%) | 301 (5.2%) | −0.009 |

| Previous Bleeding-Other (%) | 115 (2.0%) | 99 (1.7%) | 0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 0.008 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 075 (18.6%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 0.026 |

| Previous Stroke (%) | 512 (8.9%) | 535 (9.3%) | −0.014 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 28 (0.5%) | 27 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 157 (2.7%) | 131 (2.3%) | 0.026 |

| CHF (%) | 1 591 (27.6%) | 1 549 (26.9%) | 0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 851 (14.8%) | 805 (14.0%) | 0.023 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 43 (0.7%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 176 (3.1%) | 190 (3.3%) | −0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 49 (0.8%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 308 (40.0%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | −0.176 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 959 (86.0%) | 4 921 (85.3%) | 0.02 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 458 (94.6%) | 5 446 (94.4%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 534 (78.6%) | 4 481 (77.7%) | 0.022 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 825 (49.0%) | 2 689 (46.6%) | 0.048 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 789 (31.0%) | 1 739 (30.2%) | 0.017 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 4097 (0.7%) | 2597 (0.5%) | 0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 381 (0.1%) | 1745 (0.3%) | −0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 47 (0.0%) | 162 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1242 (0.2%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 0 |

| Dabigatran (n = 5 766) | Rivaroxaban (n = 5 766) | SMD | |

| (c) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban | |||

| Age, years | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | 2 946 (51.1%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.6) | 13.1 (1.7) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (11.7) | 23.5 (9.9) | 0.028 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.3 (14.7) | 21.0 (14.0) | 0.021 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 83.9 (35.7) | 84.0 (35.6) | −0.003 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.0 (72.5) | 228.3 (72.9) | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.6 (30.9) | 90.7 (30.6) | −0.036 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.3 (22.9) | 79.1 (22.2) | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.6) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 657 (46.1%) | 2 663 (46.2%) | −0.002 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 016 (87.0%) | 5 038 (87.4%) | −0.012 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 602 (10.4%) | 595 (10.3%) | 0.003 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 225 (3.9%) | 213 (3.7%) | 0.01 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 301 (5.2%) | 292 (5.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 99 (1.7%) | 116 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 987 (17.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 013 (17.6%) | 957 (16.6%) | 0.027 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 535 (9.3%) | 536 (9.3%) | 0 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 27 (0.5%) | 19 (0.3%) | 0.032 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 131 (2.3%) | 110 (1.9%) | 0.028 |

| CHF (%) | 1 548 (26.8%) | 1 585 (27.5%) | −0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 805 (14.0%) | 841 (14.6%) | −0.017 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 40 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 189 (3.3%) | 177 (3.1%) | 0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 48 (0.8%) | −0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | 2 921 (50.7%) | −0.04 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 919 (85.3%) | 4 849 (84.1%) | 0.033 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 445 (94.4%) | 5 434 (94.2%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 479 (77.7%) | 4 496 (78.0%) | −0.007 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 688 (46.6%) | 2 907 (50.4%) | −0.076 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 738 (30.1%) | 1 693 (29.4%) | 0.015 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 2596 (0.5%) | 3791 (0.7%) | −0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1745 (0.3%) | 360 (0.1%) | 0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 162 (0.0%) | 88 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 1527 (0.3%) | −0.232 |

| . | Apixaban (n = 15 668) . | Rivaroxaban (n = 15 668) . | SMD . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban . | |||

| Age, yrs | 76.2 (9.6) | 76.2 (9.6) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 7 547 (48.2%) | 7 523 (48.0%) | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.8 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | −0.017 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.0 (1.7) | 13.0 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (14.4) | 23.5 (12.8) | 0.022 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.1 (20.0) | 20.4 (15.7) | 0.039 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.5 (39.7) | 84.5 (41.6) | 0.025 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.9 (76.9) | 228.6 (73.4) | 0.017 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 90.3 (31.6) | 90.8 (30.7) | −0.016 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 76.3 (23.1) | 76.2 (23.2) | 0.004 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 4.1 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 7 537 (48.1%) | 7 521 (48.0%) | 0.002 |

| Previous hypertension (%) | 14 067 (89.8%) | 14 005 (89.4%) | 0.013 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 1 508 (9.6%) | 1 517 (9.7%) | −0.003 |

| Previous GI-bleeding (%) | 581 (3.7%) | 567 (3.6%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 723 (4.6%) | 700 (4.5%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 273 (1.7%) | 317 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 2 546 (16.2%) | 2 539 (16.2%) | 0 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 2 698 (17.2%) | 2 559 (16.3%) | 0.024 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 1 193 (7.6%) | 1 163 (7.4%) | 0.008 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 93 (0.6%) | 52 (0.3%) | 0.045 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 442 (2.8%) | 303 (1.9%) | 0.059 |

| CHF (%) | 4 701 (30.0%) | 4 768 (30.4%) | −0.009 |

| PAD (%) | 2 509 (16.0%) | 2 399 (15.3%) | 0.019 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 127 (0.8%) | 123 (0.8%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 822 (5.2%) | 867 (5.5%) | −0.013 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 94 (0.6%) | 97 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 6 509 (41.5%) | 8 127 (51.9%) | −0.21 |

| Statins use (%) | 13 367 (85.3%) | 13 234 (84.5%) | 0.022 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 14 729 (94.0%) | 0 |

| PPIs use (%) | 12 386 (79.1%) | 12 223 (78.0%) | 0.027 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 7 757 (49.5%) | 8 144 (52.0%) | −0.05 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 4 430 (28.3%) | 4 451 (28.4%) | −0.002 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 10 165 (0.6%) | 9256 (0.6%) | 0 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1406 (0.1%) | 1458 (0.1%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 142 (0.0%) | 358 (0.0%) | 0 |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 3955 (0.3%) | 4596 (0.3%) | 0 |

| Apixaban (n = 5 767) | Dabigatran (n = 5 767) | SMD | |

| (b) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban | |||

| Age, yrs | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 887 (50.1%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (6.0) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.7) | 13.1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.9 (12.1) | 23.8 (11.7) | 0.008 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.6 (19.2) | 21.5 (22.9) | 0.005 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 85.4 (39.7) | 83.9 (35.6) | 0.04 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 231.9 (79.7) | 229.0 (72.5) | 0.038 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.4 (31.9) | 89.6 (30.9) | −0.006 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.0) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.1 (22.3) | 79.3 (22.9) | −0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.5) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 721 (47.2%) | 2 659 (46.1%) | 0.022 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 049 (87.5%) | 5 018 (87.0%) | 0.015 |

| Previous Total-Bleeding (%) | 590 (10.2%) | 602 (10.4%) | −0.007 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 218 (3.8%) | 225 (3.9%) | −0.005 |

| Previous Bleeding-ICH (%) | 287 (5.0%) | 301 (5.2%) | −0.009 |

| Previous Bleeding-Other (%) | 115 (2.0%) | 99 (1.7%) | 0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 0.008 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 075 (18.6%) | 1 014 (17.6%) | 0.026 |

| Previous Stroke (%) | 512 (8.9%) | 535 (9.3%) | −0.014 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 28 (0.5%) | 27 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 157 (2.7%) | 131 (2.3%) | 0.026 |

| CHF (%) | 1 591 (27.6%) | 1 549 (26.9%) | 0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 851 (14.8%) | 805 (14.0%) | 0.023 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 43 (0.7%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 176 (3.1%) | 190 (3.3%) | −0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 49 (0.8%) | 38 (0.7%) | 0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 308 (40.0%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | −0.176 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 959 (86.0%) | 4 921 (85.3%) | 0.02 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 458 (94.6%) | 5 446 (94.4%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 534 (78.6%) | 4 481 (77.7%) | 0.022 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 825 (49.0%) | 2 689 (46.6%) | 0.048 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 789 (31.0%) | 1 739 (30.2%) | 0.017 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 4097 (0.7%) | 2597 (0.5%) | 0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 381 (0.1%) | 1745 (0.3%) | −0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 47 (0.0%) | 162 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1242 (0.2%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 0 |

| Dabigatran (n = 5 766) | Rivaroxaban (n = 5 766) | SMD | |

| (c) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban | |||

| Age, years | 74.5 (9.8) | 74.5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Male (%) | 2 916 (50.6%) | 2 946 (51.1%) | −0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (1.6) | 13.1 (1.7) | 0 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 (11.7) | 23.5 (9.9) | 0.028 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.3 (14.7) | 21.0 (14.0) | 0.021 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 83.9 (35.7) | 84.0 (35.6) | −0.003 |

| PLTs (mcL) | 229.0 (72.5) | 228.3 (72.9) | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89.6 (30.9) | 90.7 (30.6) | −0.036 |

| Creatinine (|$\mu $|mol/L) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 79.3 (22.9) | 79.1 (22.2) | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.6) | 0 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diabetic (%) | 2 657 (46.1%) | 2 663 (46.2%) | −0.002 |

| Previous Hypertension (%) | 5 016 (87.0%) | 5 038 (87.4%) | −0.012 |

| Previous total-bleeding (%) | 602 (10.4%) | 595 (10.3%) | 0.003 |

| Previous GI-Bleeding (%) | 225 (3.9%) | 213 (3.7%) | 0.01 |

| Previous bleeding-ICH (%) | 301 (5.2%) | 292 (5.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous bleeding-other (%) | 99 (1.7%) | 116 (2.0%) | −0.022 |

| Previous MI (%) | 1 000 (17.3%) | 987 (17.1%) | 0.005 |

| Previous CAD (%) | 1 013 (17.6%) | 957 (16.6%) | 0.027 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 535 (9.3%) | 536 (9.3%) | 0 |

| Previous TAVI (%) | 27 (0.5%) | 19 (0.3%) | 0.032 |

| Previous prosthetic valve (%) | 131 (2.3%) | 110 (1.9%) | 0.028 |

| CHF (%) | 1 548 (26.8%) | 1 585 (27.5%) | −0.016 |

| PAD (%) | 805 (14.0%) | 841 (14.6%) | −0.017 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 40 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Previous VTE (%) | 189 (3.3%) | 177 (3.1%) | 0.011 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 38 (0.7%) | 48 (0.8%) | −0.012 |

| Coumadin use (%) | 2 809 (48.7%) | 2 921 (50.7%) | −0.04 |

| Statins use (%) | 4 919 (85.3%) | 4 849 (84.1%) | 0.033 |

| NSAIDs use (%) | 5 445 (94.4%) | 5 434 (94.2%) | 0.009 |

| PPIs use (%) | 4 479 (77.7%) | 4 496 (78.0%) | −0.007 |

| H2 Blockers use (%) | 2 688 (46.6%) | 2 907 (50.4%) | −0.076 |

| antiplatelets use (%) | 1 738 (30.1%) | 1 693 (29.4%) | 0.015 |

| Appropriate full dose (%) | 2596 (0.5%) | 3791 (0.7%) | −0.417 |

| Appropriate reduced dose (%) | 1745 (0.3%) | 360 (0.1%) | 0.516 |

| Inappropriate full dose (%) | 162 (0.0%) | 88 (0.0%) | |

| Inappropriate reduced dose (%) | 1263 (0.2%) | 1527 (0.3%) | −0.232 |

Values are mean (±SD) or n (%). BMI, body mass index; Hb, haemoglobin; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PLTs, platelets; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GI, gastrointestinal; ICH, intra cranial haemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; CHF, congestive heart failure; PAD, peripheral artery disease; VTE, venous thromboembolism; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPIs, proton-pump inhibitors.

Data extraction, pre-processing, and analytical approach were implemented using Python (version 3.63), Lifelines package,25 (version 0.27.0), and causallib package (version 0.8.1).26

Results

Study population

Between 2010 and 2020, a total of 141 992 CHS members were treated with anticoagulants due to AF (Figure 1, Supplementary eTable 2). Of them, 68 450 patients were prescribed DOACs and 68 117 were assigned with an approved DOACs dosage for AF and therefore were eligible for the study. A total of 10 120 patients were excluded due to the target trial period, age, and an insufficient history of Clalit membership. Additionally, patients with a diagnosis of mitral stenosis (n = 874), heart transplantation (n = 12), insertion of mechanical valve (n = 418) or eGFR ≤ 30 (n = 1 222) were excluded. Finally, 56 553 patients who received DOACs were eligible for the study (Figure 1). Protocol for Target Trial Emulation is presented in Supplementary eTable 1.20

Flowchart for cohort selection. AF, atrial fibrillation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants.

Apixaban is more widely used in Israel, and is being prescribed for older patients with lower eGFR and higher CHA2DS2-VASc score (Supplementary eTable 2). Following a 1:1 propensity score matching of the treatment groups, a total of 31 336 (mean age 76.2 years), 11 534 (mean age 74.5 years), and 11 532 (mean age 74.5 years) patients were included in the apixaban/rivaroxaban, dabigatran/apixaban, and rivaroxaban/dabigatran comparison analyses, respectively. Baseline characteristics following 1:1 propensity score matching of the study groups are presented in Table 1.

Seventy-five percent of the patients assigned for dabigatran received appropriate doses (full/reduced) compared with lower rates of appropriate doses of 68.4 and 69.9% in both apixaban and dabigatran groups, respectively (Figure 2). The rates of inappropriate reduced doses were found to be higher than the rates of inappropriate full doses in all the studied groups. Inappropriate full doses of apixaban were lower (1%) compared with both rivaroxaban (2.2%) and dabigatran (2.8%) (Figure 2).

Recommended DOACs doses versus assigned doses. A contingency matrix of (A) apixaban, (B) rivaroxaban and (C) dabigatran treatment groups, displaying (x-axis) the frequency of patients by the dose they received (‘assigned’) and (y-axis) the distribution of patients by the recommended dose (as if dose assignment was according to guidelines). Patients prescribed 20 mg of rivaroxaban, 5 mg of apixaban, or 150 mg of dabigatran were considered to be receiving a ‘full dose’; Rivaroxaban 15 mg, apixaban 2.5 mg and dabigatran 110 mg were considered as ‘reduced doses’. Diagonal values showing the proportion of patients that received an ‘appropriate dose’ (full/reduced dose). Off diagonal values showing the percentage of patients receiving an ‘inappropriate dose’. Patients that should have received a full dose, but in practice they received a low dose, are considered as ‘inappropriate reduced dose’. Inappropriate full dose—when patients should have received a low dose but in practice received a full dose. Blue—appropriate full dose. Green—appropriate reduced dose. Pink—inappropriate full dose. Green—inappropriate reduced dose.

Study outcomes

The all-cause mortality rate in the rivaroxaban group was lower compared with apixaban (15.7 vs. 17.5 events per 1000 person-years; HR,0.88; 95% CI, 0.78–0.99; P,0.037; Supplementary eFigure 1, Figure 3A). The differences in the mortality rate, in favor of rivaroxaban, commenced in the third year of follow-up and was more pronounced in the younger subgroup (<70 years) (P,0.018; Supplementary eFigure 4A). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality while comparing dabigatran with apixaban (12.3 vs. 14.0 events per 1000 person-years; HR,1.18; 95% CI, 0.94 − 1.48; P,0.158; Supplementary eFigure 1, Figure 3B) and dabigatran to rivaroxaban (13.0 vs. 12.3 events per 1000 person-years; HR,1.05; 95% CI, 0.84–1.31; P,0.654; Supplementary eFigure 1, Figure 3C).

![Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (B) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (C) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ehjcvp/9/1/10.1093_ehjcvp_pvac063/1/m_pvac063fig3.jpeg?Expires=1748891437&Signature=OVs2YvXqSuwLPXdzNZBkS08WV0pyDzJ2jQ71nCkwzsd82edPlnjsm8BUwBf0doLaevmM1Uc7hsQkNIGCKRM0nUJQafa4o4eOuWD8Jj3pqZVKfD632lIdlXNUqMVkQZ9CG27VqHCkKi0ulct2hjCCKc8BfIYgQd1NsH4ppwA4bEHt7qw-AI7sC5FWasG5nmdy0kq5NDtQO5EknHBVOiKPNieyW0Qpincwts9lH6iroJtimIKWP3FaccoNYyNIRQGXYJFAePRr6XD5c9Yh8huAtMJaWmF~RUz8E3wBRixgo0gcy8vPiko1nV5VqPjO81Usva7fYYR6HukL30HYs5FvmQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (B) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (C) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.

Treatment with rivaroxaban compared with apixaban presented a lower rate of ischaemic stroke events (49.3 vs. 55.8 events per 1000 person-years; HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86–0.99; P,0.024; Supplementary eFigure 1, Figure 4A). In subgroup analysis according to age, the results were significant in the age group of 70–80 years (P,0.002; Supplementary eFigure 5A). In addition, subgroup analysis according to eGFR demonstrated significant differences in favor of rivaroxaban in patients with eGFR|$\ge $|50 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P,0.027; Supplementary eFigure 12A). The results in patients with eGFR between 30 to 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 were not significant (P,0.7; Supplementary eFigure 12A). In patients below the age of 70 years, similar superiority of rivaroxaban was noted compared with dabigatran (P,0.037; Supplementary eFigure 12C). The differences are overt even at short term follow-up (Supplementary eFigure 12C).

![Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for ischaemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (B) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (C) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring in the event of death, upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ehjcvp/9/1/10.1093_ehjcvp_pvac063/1/m_pvac063fig4.jpeg?Expires=1748891437&Signature=04MQjqFvChws5~VNoxV89e-ZdaF2xL~u03fn05WpJYJ0k0u~lxO9DLgLxVtjRvxt9-I7k0S3Xa~UGXzj7rkKCZZ-UYXEU2fjdxxvTL23zCvXUC7RcYzOuARx~~QLIZBNhTIUymESXgvMHsY2Jj5HVG3oRVBtKX9GKGWMcLN73Bkp24hGyQK9zuErnu0HAu5nYk9iyQBmA~~Y1mYBC9Vfw1XoDgyzt15qxYpNPOT2rAvnX6zu-V5EgTXbmuACGSAnGSfW5UeXyXWMi-i7mX7zmxoIhjXh28HZ7iZUsCcvplYNBvoPWk43o-X-fruyT55E67BjwOdTlu1tIeEHJALJDA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for ischaemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (B) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (C) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring in the event of death, upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.

No significant differences in the rates of MI and systemic embolism were noticed between the different DOACs groups (Figure 5, Supplementary eFigure 1).

![Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (B) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (C) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring in the event of death, upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ehjcvp/9/1/10.1093_ehjcvp_pvac063/1/m_pvac063fig5.jpeg?Expires=1748891437&Signature=qfont0eP7WQUStsW5cf-ECa3QnUeMnHivw74n3lDf5sdJK7kGh3lG8gPQ58sC7YplpGUcrIkvQ36tifugG~vZ4BjRBRumdynM-5m~2b9Bv7yEC7~GeFvmZpLJR41jbjZ4Dw3KNCWZzKm-HBEnjuXbKvO2~DhmEYGVNPsCxyvuAgUwSGxuXDOQQsb9rqSUxHlZpX4ZzRzAotGSi1ulIZJKxDpJ3ZDbXdSS2dSrLz6YwOzhWAr-mHt~jW9MBVFX7S0b6bxg0TkccEdk1RP-tRxcUncGK8RmoFJekIEWFM9hQVwtUnSHL0aVMOSGIvtgo0GkMEXCLOVLFVt01P3vRcZyg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (B) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (C) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring in the event of death, upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.

During six years of follow-up, no significant differences were observed in the rates of overall bleeding (Figure 6A, E, I). However, in subgroup analysis according to eGFR, in patients with impaired renal function with eGFR between 30 to 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, the rate of overall bleeding events was higher in the dabigatran group compared with both apixaban and rivaroxaban (P < 0.001, Supplementary eFigure 14B, P = 0.039, Supplementary eFigure 14C; respectively).

![Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for total bleeding, intra-cranial haemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding and other bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A, B, C, D) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (E, F, G, H) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (I, J, K, L) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring in the event of death, upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ehjcvp/9/1/10.1093_ehjcvp_pvac063/1/m_pvac063fig6.jpeg?Expires=1748891437&Signature=A83xLjJ1J4Ul6WyUff5EcL78vHUEOvtrjNEuudxN3rUaeUDNMrLrB~n2AY5B4PsFkV~bsq8rbOBC32O4Kidvyb1XqA4OBCdoHk0NbvMxDwwzt9CXbQZu2S0FzfztrNi2-EDjtIjNcs4zhALVypKXkCUti8Vke4c4AOifjBD9qAf2ceDC6fre6qHOnTK7d8n3gif29lu~wI-sxsV8TrHgM8AkpcEL~3hBKgq4dl-11LiYKU0bSD~9e7VKPWpoHQ8gbtv7XU9cmnDVScBV6NsQ4aIhCIJt2iQiUWw-gqZJuFmlLUoDKwDqdGqUANeAOQsxcN~5mKEYYkOVrYW3x-~Nzg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Propensity score matched KaplanMeier curves for total bleeding, intra-cranial haemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding and other bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with DOACs. A six-year follow-up of (A, B, C, D) Apixaban vs. Rivaroxaban (E, F, G, H) Dabigatran vs. Apixaban (I, J, K, L) Dabigatran vs. Rivaroxaban. Right-censoring in the event of death, upon treatment discontinuation or due to loss to follow-up. Cohort size, proportion of outcomes and censor events reported in the target trial are detailed. RMST represents the average survival time from baseline to time t = 3 (years). Hazard ratio [95% CI] estimated by univariate cox modeling (significance assessed using log rank test). Green line—Dabigatran, purple line—Apixaban, blue line—Rivaroxaban. RMST, restricted mean survival time.

The risk of ICH with rivaroxaban was lower compared with apixaban (9.4 vs. 11.6 events per 1000 person-years; HR,0.86; 95% CI, 0.74–1.0; P,0.044; Figure 6B). While comparing the rate of ICH events between rivaroxaban and dabigatran there was a trend in favor of rivaroxaban, however the results were not significant (10.25 vs. 13.3 events per 1000 person-years; HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.64–1.02; P, 0.06; Supplementary eFigure 2, Figure 6J). Nevertheless, in subgroup analysis according to age, the superiority of rivaroxaban was demonstrated compared with dabigatran, in the age group of 80 years and above (P,0.05; Supplementary eFigure 8C). The risk of GI bleeding was higher in the rivaroxaban group compared with the apixaban group (7.9 vs. 9.5 per 1000 person-years; HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.03–1.44; P, 0.016; Supplementary eFigure 2, Figure 6C). The results were significant even at a shorter follow-up period of 2 years (HR(t = 2), 1.34; P < 0.005), similar to a previous study by Ingason et al.14 The differences in GI bleeding were pronounced in the older subgroup of patients, aged 80 years and above (P,0.036; Supplementary eFigure 9A) as well as in patients with eGFR|$\ge $|50 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P,0.023; Supplementary eFigure 9A). The risk of GI bleeding did not differ in a comparison between rivaroxaban and dabigatran (Supplementary eFigure 2, Figure 6K) and dabigatran vs. apixaban (Supplementary eFigure 2, Figure 6G). However, in subgroup analysis according to renal function, a favorable effect of apixaban compared with dabigatran was observed in patients with eGFR between 30 and 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P,0.006; Supplementary eFigure 16B).

Negative control analysis showed a similar rate of herpes zoster infection in all three different DOACs groups (Supplementary eFigure 3).

Discussion

The current nationwide retrospective study, which included a total of 56 553/141 992 (39.8%) of patients treated with anticoagulants for AF, demonstrated significant differences in outcomes between the three different DOACs, rivaroxaban, apixaban and dabigatran, in the present cohort from Clalit database, as emphasized by the following main findings: (a) All-cause mortality risk was decreased in the rivaroxaban group compared with apixaban. We note that differences in survival were apparent after 3 years of follow-up. In age subgroup analysis, the reduced mortality risk of rivaroxaban compared with apixaban was significant at the younger age group of <70 years. (b) Ischaemic stroke risk in the rivaroxaban group was lower compared with apixaban. The risk for ischaemic stroke in the rivaroxaban group was also lower compared with dabigatran in the younger subgroup of patients <70 years. (c) Overall bleeding rate was higher in the dabigatran group, compared with both rivaroxaban and apixaban, in patients with impaired renal function (eGFR between 30 to 50 mL/min/1.73 m2). (d) The risk for ICH among patients in the rivaroxaban group was significantly lower compared to apixaban. Decreased rate of ICH in the rivaroxaban group compared with dabigatran, was observed in age group of 80 years and above. (e) The risk for GI bleeding was lower in the apixaban group compared with the rivaroxaban group. The differences were pronounced at the older subgroup of patients (|$\ge $|80 years). In addition, in patients with impaired renal function (eGFR between 30 and 50 mL/min/1.73 m2), lower rate of GI bleeding was observed in apixaban compared with dabigatran.

Additionally, the present study showed that in the real world, >24% of AF patients are treated with DOACs off-label doses, with the majority being under-dosed. Patients treated with dabigatran demonstrated better dose adherence to guidelines compared with both apixaban and rivaroxaban. Dose adherence to the guideline was found to be associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with AF, compared with off-label dosing which is expressed by under/overtreatment and associated with increased rate of adverse outcomes.27,28 Therefore, this finding may have a favorable effect on both efficacy and safety outcomes rates in the dabigatran group.

Even though several previous retrospective cohort studies have already examined the comparative effectiveness and safety of DOACs in AF, the present study has several strengths and thus adds important evidence and some conflicting results that justify the need for future RCTs, in order to better guide the selection of different DOACs in clinical practice. First, we used the Clalit database, which is the largest of four health organizations in Israel. Clalit provides medical services to ∼52% of Israel's highly diverse population (4.7 million) and routinely digitizes curated health records to a single database. It maintains a community network of ∼1600 clinics located throughout the country and also owns and operates a third of Israel's general hospital beds.29 Previous studies that provided comparison assessment of the available DOACs often used an administrative claims database, which indeed included larger numbers of patients, yet the information per patient was limited in terms of confounders and follow-up data.30 Second, the prescription entries in the database indicate medications dispensed by the patient de facto, which may proxy adherence of treatment and allow more accurate estimation of treatment effect. Third, the long follow-up period of 6 years revealed differences in mortality rates that are associated with prolonged use of the drugs, and probably therefore were not demonstrated in previous studies.7–11 Fourth, we implemented a robust search technique, on the entire database of AF patients (hospitalized and outpatient clinic), to identify relevant ICD-9 codes of cardiovascular and bleeding events, and identified mortality events by integrating with the national death registry data.

Finally, we used the target trial framework to explicitly emulate an observational trial while taking into account lack of randomization (by propensity score matching) and confounding (via falsification endpoint study). To overcome adherence issues, we synchronized study ‘time zero’, eligibility criteria specification, and the treatment assignment by estimating analog of the per-protocol effect.31 Such strategy also aims to reduce common biases such as selection and immortal time bias in the effect estimates.16

Our study has several limitations. The main limitation is the observational nature of the study, even though we used the target trial framework, and as such might still experience residual confounding even after adjustment for key patient covariates. Furthermore, the dabigatran group was significantly smaller compared with the rivaroxaban and apixaban groups, causing the head-to-head matched population with dabigatran to be smaller and less representative. The differences in cohort sizes may also reflect the natural bias of clinicians in Israel towards a specific drug. Finally, a recent observational study among Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older with AF showed that treatment with rivaroxaban compared with apixaban was associated with a significantly increased risk of major ischaemic or haemorrhagic events in the apixaban group in a 4 years follow-up;32 Seemingly, these findings are inconsistent with the present study, however, our results showed that both age and follow-up period may affect the risk for ischaemic stroke and bleeding, respectively, and our cohort is not aligned with the Medicare cohort accordingly. In addition, unlike the present study, Ray et al. combined both efficacy and safety outcomes.32

To conclude, the present study from Clalit database demonstrated differences in outcomes between all available DOACs in Israel (apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran). The long follow-up data of 6 years may reveal differences in mortality risk in favor of rivaroxaban that were not demonstrated in previous studies in which the follow-up period was shorter. We showed that the differences in mortality and ischaemic stroke are age-related. In addition, the bleeding rates were higher in the dabigatran group in patients with impaired renal function and in elderly (80 years and above). A comparison between apixaban and rivaroxaban revealed decreased GI bleeding in the apixaban group, and on the other hand, decreased ICH in the rivaroxaban group. We believe that the present study emphasizes the need for future RCTs that will compare apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran in order to better guide the use of the different DOACs in clinical practice.

Funding

N.S.Y is partially supported by the Israeli Council for Higher Education (CHE) via the Weizmann Data Science Research Center.

Conflict of interest: The authors have nothing to declare.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study originate from Clalit Healthcare Services. All data analyses were conducted on a secured, de-identified dedicated server within the Clalit Healthcare environment. Requests for access to all of parts of the Clalit datasets should be addressed to Clalit Healthcare Services, via the Clalit Research Institute.

References

Author notes

These authors contributed equally to this work.

These authors jointly supervised this work.