-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tineke H Pinxterhuis, Eline H Ploumen, Carine J M Doggen, Marc Hartmann, Carl E Schotborgh, Rutger L Anthonio, Ariel Roguin, Peter W Danse, Edouard Benit, Adel Aminian, Gerard C M Linssen, Clemens von Birgelen, First myocardial infarction in patients with premature coronary artery disease: insights into patient characteristics and outcome after treatment with contemporary stents, European Heart Journal. Acute Cardiovascular Care, Volume 12, Issue 11, November 2023, Pages 774–781, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuad098

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patients with premature coronary artery disease (CAD) have a higher incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) than patients with non-premature CAD. The aim of the present study is to asess differences in clinical outcome after a first acute MI, percutaneously treated with new-generation drug-eluting stents between patients with premature and non-premature CAD.

We pooled and analysed the characteristics and clinical outcome of all patients with a first MI (and no previous coronary revascularization) at time of enrolment, in four large-scale drug-eluting stent trials. Coronary artery disease was classified premature in men aged <50 and women <55 years. Myocardial infarction patients with premature and non-premature CAD were compared. The main endpoint was major adverse cardiac events (MACE): all-cause mortality, any MI, emergent coronary artery bypass surgery, or clinically indicated target lesion revascularization. Of 3323 patients with a first MI, 582 (17.5%) had premature CAD. These patients had lower risk profiles and underwent less complex interventional procedures than patients with non-premature CAD. At 30-day follow-up, the rates of MACE [hazard ratio (HR): 0.22, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.07–0.71; P = 0.005), MI (HR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.05–0.89; P = 0.020), and target vessel failure (HR: 0.30, 95% CI: 0.11–0.82; P = 0.012) were lower in patients with premature CAD. At 1 year, premature CAD was independently associated with lower rates of MACE (adjusted HR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.26–0.96; P = 0.037) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR: 0.24, 95% CI: 0.06–0.98; P = 0.046). At 2 years, premature CAD was independently associated with lower mortality (adjusted HR: 0.16, 95% CI: 0.05–0.50; P = 0.002).

First MI patients with premature CAD, treated with contemporary stents, showed lower rates of MACE and all-cause mortality than patients with non-premature CAD, which is most likely related to differences in cardiovascular risk profile.

TWENTE trials: TWENTE I, clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01066650), DUTCH PEERS (TWENTE II, NCT01331707), BIO-RESORT (TWENTE III, NCT01674803), and BIONYX (TWENTE IV, NCT02508714)

Comparison of patients with premature and non-premature coronary artery disease. CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is an important cause of cardiac mortality and can result in serious morbidity, even in young adults.1 A substantial proportion of all patients, who present with an acute MI and undergo acute percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), are relatively young and have premature coronary artery disease (CAD).2,3 Over time, the incidence of an acute MI has decreased in middle-aged and older patients, while in young patients, the incidence rate remained stable or has increased.2,4–6 Various potential reasons for this divergence in trends between both age groups have been suggested, including dissimilarities in the main pathophysiological mechanism of MI, differences in the patients’ risk profiles,2,4–6 and alterations in the definition of ‘premature’ CAD.2,7–10

In previous research, mortality was lower in young MI patients than in both middle-aged and older MI patients. Furthermore, young MI patients had a lower incidence of recurrent MI than older patients.11 Notably, most previous data on the outcome of MI patients with premature CAD were derived from pooling studies and from clinical registries that assessed patients after non-invasive or invasive treatment, including the implantation of different generations of coronary stents.8,11,12

It is greatly unknown whether the clinical outcome after PCI with contemporary drug-eluting stents (DES) differs between MI patients with premature CAD and those with non-premature CAD. In addition, information about potential differences between patients with premature and non-premature CAD in modifiable risk factors, and in treatment options, is scarce. To compare the risk profile and 2-year clinical outcome after PCI for acute MI in patients with premature or non-premature CAD, we assessed clinical data of participants in four randomized DES trials, who at the time of enrolment were treated for their first MI and had no history of coronary revascularization.

Patients and methods

Study design

The present pooled data analysis was performed in all-comer participants of the TWENTE (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01066650), DUTCH PEERS (TWENTE II, NCT01331707), BIO-RESORT (TWENTE III, NCT01674803), and BIONYX (TWENTE IV, NCT02508714) trials. Details of the original trials have been reported previously.13–16

Briefly, the four investigator-initiated, patient-blinded, randomized trials included 9204 patients who underwent PCI in six Dutch centres, two Belgian centres, and one Israeli centre. In all trials, inclusion criteria were broad, and patients were eligible for participation if they were aged 18 years or older, capable of providing informed consent, and required PCI with DES implantation. The DUTCH PEERS, BIO-RESORT, and BIONYX trials enrolled all-comer patients with any clinical syndrome, while TWENTE enrolled patients with any clinical syndrome, except for ST-segment elevation MI during the last 48 h. Randomization was performed in a 1:1 fashion in the TWENTE, DUTCH PEERS, and BIONYX trials, whereas the three-arm BIO-RESORT trial had a 1:1:1 randomization. Randomization in BIO-RESORT and BIONYX was stratified for diabetes, and in TWENTE and BIONYX, randomization was stratified for sex. The Medical Ethics Committee Twente and the Institutional Review Boards of all participating centres approved the original trials. In addition, the four trials complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

In the present analysis, we pooled data on demographic, clinical, and angiographic characteristics (at time of the index procedure) as well as clinical outcome of all trial participants who were enrolled at the time of their first acute MI and had no history of coronary revascularization. Then, we compared the patient, lesion, and procedure characteristics as well as the clinical outcome of patients with premature and non-premature CAD. Premature CAD was defined as CAD in men aged <50 years and women <55 years.

Procedures, follow-up, and monitoring

Coronary interventions and concomitant pharmacological treatment were performed according to standard techniques, international medical guidelines, and operator’s judgment. Generally, dual antiplatelet therapy was prescribed for 12 months in case of acute coronary syndrome. Questionnaires, patient visits to outpatient clinics, and telephone-based follow-up were used to obtain follow-up information. Adverse events were externally adjudicated by independent, blinded clinical event committees.

Definitions

The main endpoint of this study was major adverse cardiac events (MACE), a composite of all-cause mortality, any MI, emergent coronary artery bypass surgery, or clinically indicated target lesion revascularization. Several secondary endpoints were assessed, including target vessel failure (TVF) (cardiac death, target vessel MI, or clinically indicated target vessel revascularization), the individual components of the composite endpoints, and stent thrombosis. All clinical endpoints were pre-specified according to recommendations of the Academic Research Consortium.17,18

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and differences were assessed with the Wilcoxon rank sum test or Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Dichotomous and categorical variables were reported as frequencies with percentages, and differences were assessed with the chi-square test. Kaplan–Meier statistics were used to assess time to endpoints, and the log-rank test was applied for between-group comparisons. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and provided a two-sided confidence interval (CI). Potential confounders were identified if in univariate analysis a P-value of <0.15 was found. These potential confounders were diabetes, smoking, renal insufficiency, stroke, reduced left ventricular function, treatment of severely calcified lesion, treatment of ostial lesion, multi-vessel treatment, treatment of a chronic total occlusion, and inclusion period (i.e. trial). The potential confounders were included in the first multivariate Cox regression model. Other variables such as age, gender, body mass index, hypertension, peripheral arterial disease, family history of CAD, and clinical syndrome at presentation were found not to be potential confounders. Stepwise backward selection was used to exclude variables with a non-significant association with the main endpoint, and only the true confounders [diabetes, stroke, renal insufficiency, treatment of severely calcified lesion, and inclusion period (trial)] were kept in the model. To assess the goodness of fit of the multivariable model, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test was applied, revealing a (favourable) P-value for MACE and TVF (1-year MACE P = 0.51; 2-year MACE P = 0.73; 1-year TVF P = 0.39; 2-year TVF P = 0.70). P-values and confidence intervals were two sided, and P-values of <0.05 were considered significant. SPSS version 28 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

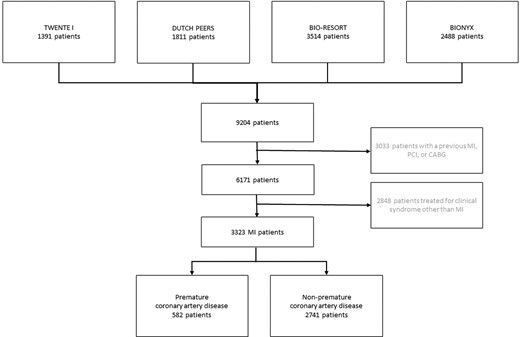

Of all 9204 trial participants, 3323 study patients presented with an acute MI and had no history of MI, coronary artery bypass surgery, or PCI. Of this study population, 582 (17.5%) patients had premature CAD (Figure 1).

Flowchart. The number of patients who presented with an acute myocardial infarction, stratified by premature coronary artery disease. CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Patients with premature CAD had fewer risk factors and co-morbidities than patients with non-premature CAD, including diabetes, hypertension, peripheral arterial disease, and renal failure. Yet, patients with premature CAD were more often smokers and had on average a higher body mass index and more often a family history of CAD. The procedural characteristics also differed between patients with premature and non-premature CAD: patients with premature CAD were less often treated in multiple vessels and in calcified or bifurcated lesions, and they had a lower total length of implanted stents (Table 1). During the first 30 days after PCI, patients with premature CAD had lower rates of various clinical endpoints, including MACE (HR: 0.11, 95% CI: 0.02–0.79; P = 0.008), and TVF (HR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.05–0.92; P = 0.023) (Table 2). Yet, definite or probable stent thrombosis (0.2% vs. 0.2%; HR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.09–6.52; P = 0.82) and definite stent thrombosis (0.2% vs. 0.2%; HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.13–10.53; P = 0.88) showed no significant difference between the groups.

Baseline and procedural characteristics for myocardial infarction patients with premature or non-premature coronary artery disease

| General characteristics . | Premature coronary artery disease . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | ||

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 4.9 | 65.0 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Women | 177 (30.4) | 746 (27.2) | 0.12 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 4.8 | 27.3 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 402/577 (69.7) | 915/2685 (34.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (9.5) | 398 (14.5) | 0.001 |

| Renal failurea | 6 (1.0) | 85 (3.1) | 0.005 |

| Hypertension | 152/581 (26.2) | 1194/2727 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 162/577 (28.2) | 821/2713 (30.3) | 0.34 |

| Previous stroke | 7 (1.2) | 123 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| PADsb | 8 (1.4) | 137 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| LVEF < 30% | 1 (0.2) | 10 (0.4) | 0.46 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 321/573 (56.0) | 1093/2664 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| Clinical syndrome at presentation | <0.001 | ||

| STEMI | 358 (61.5) | 1464 (53.4) | |

| Non-STEMI | 224 (38.5) | 1277 (46.6) | |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| Multi-vessel treatment | 58 (10.0) | 464 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Target vessel | |||

| Left main | 2 (0.3) | 27 (1.0) | 0.13 |

| Right coronary artery | 228 (39.2) | 1068 (39.0) | 0.92 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 277 (47.6) | 1377 (50.2) | 0.25 |

| Left circumflex artery | 135 (23.2) | 784 (28.6) | 0.008 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 32.6 ± 20.2 | 36.4 ± 24.3 | 0.001 |

| Calcified lesion treatment | 55 (9.5) | 476 (17.4) | <0.001 |

| Ostial lesion treatment | 22 (3.8) | 121 (4.4) | 0.49 |

| Bifurcated lesion treatmentc | 152 (26.1) | 916 (33.4) | 0.001 |

| Chronic total occlusion treatment | 12 (2.1) | 37 (1.9) | 0.20 |

| General characteristics . | Premature coronary artery disease . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | ||

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 4.9 | 65.0 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Women | 177 (30.4) | 746 (27.2) | 0.12 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 4.8 | 27.3 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 402/577 (69.7) | 915/2685 (34.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (9.5) | 398 (14.5) | 0.001 |

| Renal failurea | 6 (1.0) | 85 (3.1) | 0.005 |

| Hypertension | 152/581 (26.2) | 1194/2727 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 162/577 (28.2) | 821/2713 (30.3) | 0.34 |

| Previous stroke | 7 (1.2) | 123 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| PADsb | 8 (1.4) | 137 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| LVEF < 30% | 1 (0.2) | 10 (0.4) | 0.46 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 321/573 (56.0) | 1093/2664 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| Clinical syndrome at presentation | <0.001 | ||

| STEMI | 358 (61.5) | 1464 (53.4) | |

| Non-STEMI | 224 (38.5) | 1277 (46.6) | |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| Multi-vessel treatment | 58 (10.0) | 464 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Target vessel | |||

| Left main | 2 (0.3) | 27 (1.0) | 0.13 |

| Right coronary artery | 228 (39.2) | 1068 (39.0) | 0.92 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 277 (47.6) | 1377 (50.2) | 0.25 |

| Left circumflex artery | 135 (23.2) | 784 (28.6) | 0.008 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 32.6 ± 20.2 | 36.4 ± 24.3 | 0.001 |

| Calcified lesion treatment | 55 (9.5) | 476 (17.4) | <0.001 |

| Ostial lesion treatment | 22 (3.8) | 121 (4.4) | 0.49 |

| Bifurcated lesion treatmentc | 152 (26.1) | 916 (33.4) | 0.001 |

| Chronic total occlusion treatment | 12 (2.1) | 37 (1.9) | 0.20 |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%) or n/N (%). Procedures present patient-level data.

Italic values are statistically significant.

aDefined as previous renal failure, creatinine ≥ 130 μmol/L, or the need for dialysis.

bDefined as a history of symptomatic atherosclerotic lesion in the lower or upper extremities, atherosclerotic lesion in the aorta-causing symptoms or requiring treatment, atherosclerotic lesion in the carotid or vertebral arteries related to a non-embolic ischaemic cerebrovascular event, or symptomatic atherosclerotic lesion in a mesenteric artery.

cTarget lesions were classified as bifurcated if a side branch ≥ 1.5 mm originated from them.

LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; non-STEMI, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PADs, peripheral arterial disease; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Baseline and procedural characteristics for myocardial infarction patients with premature or non-premature coronary artery disease

| General characteristics . | Premature coronary artery disease . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | ||

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 4.9 | 65.0 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Women | 177 (30.4) | 746 (27.2) | 0.12 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 4.8 | 27.3 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 402/577 (69.7) | 915/2685 (34.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (9.5) | 398 (14.5) | 0.001 |

| Renal failurea | 6 (1.0) | 85 (3.1) | 0.005 |

| Hypertension | 152/581 (26.2) | 1194/2727 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 162/577 (28.2) | 821/2713 (30.3) | 0.34 |

| Previous stroke | 7 (1.2) | 123 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| PADsb | 8 (1.4) | 137 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| LVEF < 30% | 1 (0.2) | 10 (0.4) | 0.46 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 321/573 (56.0) | 1093/2664 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| Clinical syndrome at presentation | <0.001 | ||

| STEMI | 358 (61.5) | 1464 (53.4) | |

| Non-STEMI | 224 (38.5) | 1277 (46.6) | |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| Multi-vessel treatment | 58 (10.0) | 464 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Target vessel | |||

| Left main | 2 (0.3) | 27 (1.0) | 0.13 |

| Right coronary artery | 228 (39.2) | 1068 (39.0) | 0.92 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 277 (47.6) | 1377 (50.2) | 0.25 |

| Left circumflex artery | 135 (23.2) | 784 (28.6) | 0.008 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 32.6 ± 20.2 | 36.4 ± 24.3 | 0.001 |

| Calcified lesion treatment | 55 (9.5) | 476 (17.4) | <0.001 |

| Ostial lesion treatment | 22 (3.8) | 121 (4.4) | 0.49 |

| Bifurcated lesion treatmentc | 152 (26.1) | 916 (33.4) | 0.001 |

| Chronic total occlusion treatment | 12 (2.1) | 37 (1.9) | 0.20 |

| General characteristics . | Premature coronary artery disease . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | ||

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 4.9 | 65.0 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Women | 177 (30.4) | 746 (27.2) | 0.12 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 4.8 | 27.3 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 402/577 (69.7) | 915/2685 (34.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (9.5) | 398 (14.5) | 0.001 |

| Renal failurea | 6 (1.0) | 85 (3.1) | 0.005 |

| Hypertension | 152/581 (26.2) | 1194/2727 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 162/577 (28.2) | 821/2713 (30.3) | 0.34 |

| Previous stroke | 7 (1.2) | 123 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| PADsb | 8 (1.4) | 137 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| LVEF < 30% | 1 (0.2) | 10 (0.4) | 0.46 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 321/573 (56.0) | 1093/2664 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| Clinical syndrome at presentation | <0.001 | ||

| STEMI | 358 (61.5) | 1464 (53.4) | |

| Non-STEMI | 224 (38.5) | 1277 (46.6) | |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| Multi-vessel treatment | 58 (10.0) | 464 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Target vessel | |||

| Left main | 2 (0.3) | 27 (1.0) | 0.13 |

| Right coronary artery | 228 (39.2) | 1068 (39.0) | 0.92 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 277 (47.6) | 1377 (50.2) | 0.25 |

| Left circumflex artery | 135 (23.2) | 784 (28.6) | 0.008 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 32.6 ± 20.2 | 36.4 ± 24.3 | 0.001 |

| Calcified lesion treatment | 55 (9.5) | 476 (17.4) | <0.001 |

| Ostial lesion treatment | 22 (3.8) | 121 (4.4) | 0.49 |

| Bifurcated lesion treatmentc | 152 (26.1) | 916 (33.4) | 0.001 |

| Chronic total occlusion treatment | 12 (2.1) | 37 (1.9) | 0.20 |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%) or n/N (%). Procedures present patient-level data.

Italic values are statistically significant.

aDefined as previous renal failure, creatinine ≥ 130 μmol/L, or the need for dialysis.

bDefined as a history of symptomatic atherosclerotic lesion in the lower or upper extremities, atherosclerotic lesion in the aorta-causing symptoms or requiring treatment, atherosclerotic lesion in the carotid or vertebral arteries related to a non-embolic ischaemic cerebrovascular event, or symptomatic atherosclerotic lesion in a mesenteric artery.

cTarget lesions were classified as bifurcated if a side branch ≥ 1.5 mm originated from them.

LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; non-STEMI, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PADs, peripheral arterial disease; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

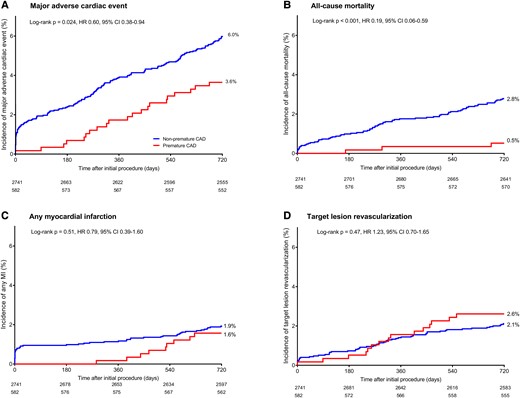

The 1-year rates of MACE (HR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.23–0.83; P = 0.010), TVF (HR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.27–0.95; P = 0.003), all-cause mortality (HR: 0.20, 95% CI: 0.05–0.80; P = 0.012), and any (recurrent) MI (HR: 0.15, 95% CI: 0.02–1.11; P = 0.031) were lower in patients with premature CAD. Definite or probable stent thrombosis (0.5% vs. 0.3%; HR: 2.01, 95% CI: 0.52–7.79; P = 0.30) and definite stent thrombosis (0.5% vs. 0.2%; HR: 2.82, 95% CI: 0.67–11.80; P = 0.14) showed no between-group differences. After adjustment for confounders, premature CAD was found to be associated with lower rates of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR: 0.24, 95% CI: 0.06–0.98; P = 0.046) and MACE (adjusted HR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.26–0.96; P = 0.037) at 1-year follow-up. No statistically significant association was found between premature CAD and the secondary endpoints TVF (adjusted HR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.30–1.05; P = 0.07) and any (recurrent) MI (adjusted HR: 0.17, 95% CI: 0.02–1.28; P = 0.08) at 1 year.

At 2-year follow-up, the rates of MACE (HR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.38–0.94; P = 0.024), all-cause mortality (HR: 0.19, 95% CI: 0.06–0.59; P < 0.001), and cardiac mortality (HR: 0.14, 95% CI: 0.02–1.04; P = 0.025) were lower in patients with premature CAD. Yet, definite or probable stent thrombosis (0.9% vs. 0.5%; HR: 1.68, 95% CI: 0.60–4.65; P = 0.32) and definite stent thrombosis (0.9% vs. 0.4%; HR: 2.35, 95% CI: 0.80–6.86; P = 0.11) showed no significant difference between patients with premature and non-premature CAD. After adjustment for confounders, premature CAD was an independent predictor of lower all-cause mortality (adjusted HR: 0.16, 95% CI: 0.05–0.50; P = 0.002) and cardiac mortality (adjusted HR: 0.13, 95% CI: 0.02–0.97; P = 0.047) after 2 years, but not of MACE (adjusted HR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.49–1.06; P = 0.10) (Figure 2).

Kaplan–Meier cumulative adverse event curves at 2-year follow-up in myocardial infarction patients with premature and non-premature coronary artery disease. Kaplan–Meier cumulative incidence curves for (A) the primary endpoint major adverse cardiac events, (B) all-cause mortality, (C) any myocardial infarction, and (D) target lesion revascularization. CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction.

Discussion

Main findings

One out of six patients who presented with their first acute MI and were treated with PCI had premature CAD. These young MI patients had less complex cardiovascular risk profiles, including lower rates of diabetes, hypertension, renal failure, and peripheral arterial disease. Yet, they had more often a family history of CAD and were more often smokers and overweight. Furthermore, patients with premature CAD had less complex target lesions and were less often treated in multiple vessels and in calcified or bifurcated lesions. During follow-up, premature CAD was independently associated with lower MACE and mortality risks, but the incidence of another MI and the rates of repeated revascularization did not differ between patients with premature and non-premature CAD.

Incidence of premature coronary artery disease

In patients aged 40–59 years, treated from 2015 to 2018, the American Heart Association reported the prevalence of acute MI to be 3.2% in men and 1.9% in women.19 Among all MI patients undergoing PCI in the USA, the incidence of premature CAD has been reported to be 20% to 30%.2,3 In the present analysis in mostly Western European patients with a first acute MI but no previous coronary revascularization, the proportion of patients with premature CAD was only slightly lower (18%). In young individuals, over the years, a stabilization or even an increase in the incidence of MI and in the prevalence of premature CAD has been observed.2,3,19,20 Changes in cardiovascular risk profile may explain the generally higher incidence of MI among young patients.21 The increase in the incidence of MI has been seen particularly in young women who now represent about a quarter up to a third of all women with an MI, while among all men with an MI the proportion of the young remained similar.2,3 In the current analysis, 30% of the MI patients with premature CAD were female, which is comparable with the findings of previous reports.2,3

The between-study difference in the incidence of premature CAD may partly be explained by differences in the definition of ‘premature’ (i.e. age threshold) and study population (i.e. any acute coronary syndrome, all MI, or only ST-segment–elevated MI).2,7–9 Furthermore, some studies used the same age threshold for both sexes, while others applied different cut-off points in women and men, as women generally develop atherosclerosis somewhat later than men.10 Differences in age threshold and patient population are likely to have some impact on the results of studies reporting clinical outcomes after PCI, which renders between-study comparisons difficult (Table 2).

Clinical outcomes at 30 days and 1- and 2-years for myocardial infarction patients with premature or non-premature coronary artery disease

| . | Premature coronary artery disease . | . | . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | HR (95% CI) . | Plog-rank . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)c . | Plog-rank . |

| 30 days | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 1 (0.2) | 43 (1.6) | 0.11 (0.02–0.79) | 0.008 | — | — |

| Target vessel failureb | 2 (0.3) | 42 (1.5) | 0.22 (0.05–0.92) | 0.023 | — | — |

| All-cause death | 0 | 12 (0.5) | — | — | — | — |

| Cardiac death | 0 | 9 (0.3) | — | — | — | — |

| Any myocardial infarction | 0 | 26 (1.0) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 0 | 23 (0.8) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel revascularization | 2 (0.3) | 16 (0.6) | 0.59 (0.14–2.56) | 0.47 | — | — |

| Target lesion revascularization | 1 (0.2) | 11 (0.4) | 0.43 (0.06–3.31) | 0.40 | — | — |

| 1 year | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 10 (1.7) | 107 (3.9) | 0.44 (0.23–0.83) | 0.010 | 0.50 (0.26–0.96) | 0.037 |

| Target vessel failureb | 11 (1.9) | 101 (3.7) | 0.51 (0.27–0.95) | 0.003 | 0.56 (0.30–1.05) | 0.07 |

| All-cause death | 2 (0.3) | 48 (1.8) | 0.20 (0.05–0.80) | 0.012 | 0.24 (0.06–0.98) | 0.046 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.22 (0.03–1.60) | 0.13 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 31 (1.1) | 0.15 (0.02–1.11) | 0.031 | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.08 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.21 (0.03–1.54) | 0.12 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 11 (1.9) | 60 (2.2) | 0.86 (0.45–1.63) | 0.64 | 0.90 (0.47–1.73) | 0.76 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 9 (1.6) | 38 (1.4) | 1.10 (0.54–2.30) | 0.78 | 1.27 (0.61–2.66) | 0.53 |

| 2 years | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 21 (3.6) | 164 (6.0) | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.024 | 0.72 (0.49–1.06) | 0.10 |

| Target vessel failureb | 21 (3.6) | 136 (5.0) | 0.72 (0.45–1.14) | 0.20 | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | 0.81 |

| All-cause death | 3 (0.5) | 76 (2.8) | 0.19 (0.06–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.05–0.50) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 33 (1.2) | 0.14 (0.02–1.04) | 0.025 | 0.13 (0.02–0.97) | 0.047 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 9 (1.6) | 53 (1.9) | 0.79 (0.39–1.60) | 0.51 | 1.03 (0.56–1.87) | 0.94 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 6 (1.0) | 40 (1.5) | 0.70 (0.30–1.65) | 0.41 | 0.78 (0.35–1.74) | 0.55 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 20 (3.5) | 85 (3.2) | 1.10 (0.68–1.79) | 0.71 | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.14 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 15 (2.6) | 57 (2.1) | 1.23 (0.70–2.18) | 0.47 | 1.48 (0.90–2.46) | 0.12 |

| . | Premature coronary artery disease . | . | . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | HR (95% CI) . | Plog-rank . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)c . | Plog-rank . |

| 30 days | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 1 (0.2) | 43 (1.6) | 0.11 (0.02–0.79) | 0.008 | — | — |

| Target vessel failureb | 2 (0.3) | 42 (1.5) | 0.22 (0.05–0.92) | 0.023 | — | — |

| All-cause death | 0 | 12 (0.5) | — | — | — | — |

| Cardiac death | 0 | 9 (0.3) | — | — | — | — |

| Any myocardial infarction | 0 | 26 (1.0) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 0 | 23 (0.8) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel revascularization | 2 (0.3) | 16 (0.6) | 0.59 (0.14–2.56) | 0.47 | — | — |

| Target lesion revascularization | 1 (0.2) | 11 (0.4) | 0.43 (0.06–3.31) | 0.40 | — | — |

| 1 year | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 10 (1.7) | 107 (3.9) | 0.44 (0.23–0.83) | 0.010 | 0.50 (0.26–0.96) | 0.037 |

| Target vessel failureb | 11 (1.9) | 101 (3.7) | 0.51 (0.27–0.95) | 0.003 | 0.56 (0.30–1.05) | 0.07 |

| All-cause death | 2 (0.3) | 48 (1.8) | 0.20 (0.05–0.80) | 0.012 | 0.24 (0.06–0.98) | 0.046 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.22 (0.03–1.60) | 0.13 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 31 (1.1) | 0.15 (0.02–1.11) | 0.031 | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.08 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.21 (0.03–1.54) | 0.12 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 11 (1.9) | 60 (2.2) | 0.86 (0.45–1.63) | 0.64 | 0.90 (0.47–1.73) | 0.76 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 9 (1.6) | 38 (1.4) | 1.10 (0.54–2.30) | 0.78 | 1.27 (0.61–2.66) | 0.53 |

| 2 years | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 21 (3.6) | 164 (6.0) | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.024 | 0.72 (0.49–1.06) | 0.10 |

| Target vessel failureb | 21 (3.6) | 136 (5.0) | 0.72 (0.45–1.14) | 0.20 | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | 0.81 |

| All-cause death | 3 (0.5) | 76 (2.8) | 0.19 (0.06–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.05–0.50) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 33 (1.2) | 0.14 (0.02–1.04) | 0.025 | 0.13 (0.02–0.97) | 0.047 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 9 (1.6) | 53 (1.9) | 0.79 (0.39–1.60) | 0.51 | 1.03 (0.56–1.87) | 0.94 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 6 (1.0) | 40 (1.5) | 0.70 (0.30–1.65) | 0.41 | 0.78 (0.35–1.74) | 0.55 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 20 (3.5) | 85 (3.2) | 1.10 (0.68–1.79) | 0.71 | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.14 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 15 (2.6) | 57 (2.1) | 1.23 (0.70–2.18) | 0.47 | 1.48 (0.90–2.46) | 0.12 |

Data are n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Italic values are statistically significant.

aMajor adverse cardiac events is a composite of all-cause death, any myocardial infarction, emergent coronary artery bypass surgery, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization.

bTarget vessel failure is a composite of cardiac death, target vessel–related myocardial infarction, and clinically indicated target vessel revascularization.

cAt 30-days, no multivariable analysis was performed as the number of events was low.

Clinical outcomes at 30 days and 1- and 2-years for myocardial infarction patients with premature or non-premature coronary artery disease

| . | Premature coronary artery disease . | . | . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | HR (95% CI) . | Plog-rank . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)c . | Plog-rank . |

| 30 days | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 1 (0.2) | 43 (1.6) | 0.11 (0.02–0.79) | 0.008 | — | — |

| Target vessel failureb | 2 (0.3) | 42 (1.5) | 0.22 (0.05–0.92) | 0.023 | — | — |

| All-cause death | 0 | 12 (0.5) | — | — | — | — |

| Cardiac death | 0 | 9 (0.3) | — | — | — | — |

| Any myocardial infarction | 0 | 26 (1.0) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 0 | 23 (0.8) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel revascularization | 2 (0.3) | 16 (0.6) | 0.59 (0.14–2.56) | 0.47 | — | — |

| Target lesion revascularization | 1 (0.2) | 11 (0.4) | 0.43 (0.06–3.31) | 0.40 | — | — |

| 1 year | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 10 (1.7) | 107 (3.9) | 0.44 (0.23–0.83) | 0.010 | 0.50 (0.26–0.96) | 0.037 |

| Target vessel failureb | 11 (1.9) | 101 (3.7) | 0.51 (0.27–0.95) | 0.003 | 0.56 (0.30–1.05) | 0.07 |

| All-cause death | 2 (0.3) | 48 (1.8) | 0.20 (0.05–0.80) | 0.012 | 0.24 (0.06–0.98) | 0.046 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.22 (0.03–1.60) | 0.13 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 31 (1.1) | 0.15 (0.02–1.11) | 0.031 | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.08 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.21 (0.03–1.54) | 0.12 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 11 (1.9) | 60 (2.2) | 0.86 (0.45–1.63) | 0.64 | 0.90 (0.47–1.73) | 0.76 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 9 (1.6) | 38 (1.4) | 1.10 (0.54–2.30) | 0.78 | 1.27 (0.61–2.66) | 0.53 |

| 2 years | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 21 (3.6) | 164 (6.0) | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.024 | 0.72 (0.49–1.06) | 0.10 |

| Target vessel failureb | 21 (3.6) | 136 (5.0) | 0.72 (0.45–1.14) | 0.20 | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | 0.81 |

| All-cause death | 3 (0.5) | 76 (2.8) | 0.19 (0.06–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.05–0.50) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 33 (1.2) | 0.14 (0.02–1.04) | 0.025 | 0.13 (0.02–0.97) | 0.047 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 9 (1.6) | 53 (1.9) | 0.79 (0.39–1.60) | 0.51 | 1.03 (0.56–1.87) | 0.94 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 6 (1.0) | 40 (1.5) | 0.70 (0.30–1.65) | 0.41 | 0.78 (0.35–1.74) | 0.55 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 20 (3.5) | 85 (3.2) | 1.10 (0.68–1.79) | 0.71 | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.14 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 15 (2.6) | 57 (2.1) | 1.23 (0.70–2.18) | 0.47 | 1.48 (0.90–2.46) | 0.12 |

| . | Premature coronary artery disease . | . | . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Yes (n = 582) . | No (n = 2741) . | HR (95% CI) . | Plog-rank . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)c . | Plog-rank . |

| 30 days | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 1 (0.2) | 43 (1.6) | 0.11 (0.02–0.79) | 0.008 | — | — |

| Target vessel failureb | 2 (0.3) | 42 (1.5) | 0.22 (0.05–0.92) | 0.023 | — | — |

| All-cause death | 0 | 12 (0.5) | — | — | — | — |

| Cardiac death | 0 | 9 (0.3) | — | — | — | — |

| Any myocardial infarction | 0 | 26 (1.0) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 0 | 23 (0.8) | — | — | — | — |

| Target vessel revascularization | 2 (0.3) | 16 (0.6) | 0.59 (0.14–2.56) | 0.47 | — | — |

| Target lesion revascularization | 1 (0.2) | 11 (0.4) | 0.43 (0.06–3.31) | 0.40 | — | — |

| 1 year | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 10 (1.7) | 107 (3.9) | 0.44 (0.23–0.83) | 0.010 | 0.50 (0.26–0.96) | 0.037 |

| Target vessel failureb | 11 (1.9) | 101 (3.7) | 0.51 (0.27–0.95) | 0.003 | 0.56 (0.30–1.05) | 0.07 |

| All-cause death | 2 (0.3) | 48 (1.8) | 0.20 (0.05–0.80) | 0.012 | 0.24 (0.06–0.98) | 0.046 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.22 (0.03–1.60) | 0.13 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 31 (1.1) | 0.15 (0.02–1.11) | 0.031 | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.08 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.0) | 0.17 (0.02–1.28) | 0.051 | 0.21 (0.03–1.54) | 0.12 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 11 (1.9) | 60 (2.2) | 0.86 (0.45–1.63) | 0.64 | 0.90 (0.47–1.73) | 0.76 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 9 (1.6) | 38 (1.4) | 1.10 (0.54–2.30) | 0.78 | 1.27 (0.61–2.66) | 0.53 |

| 2 years | ||||||

| Major adverse cardiac eventsa | 21 (3.6) | 164 (6.0) | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.024 | 0.72 (0.49–1.06) | 0.10 |

| Target vessel failureb | 21 (3.6) | 136 (5.0) | 0.72 (0.45–1.14) | 0.20 | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | 0.81 |

| All-cause death | 3 (0.5) | 76 (2.8) | 0.19 (0.06–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.05–0.50) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.2) | 33 (1.2) | 0.14 (0.02–1.04) | 0.025 | 0.13 (0.02–0.97) | 0.047 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 9 (1.6) | 53 (1.9) | 0.79 (0.39–1.60) | 0.51 | 1.03 (0.56–1.87) | 0.94 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 6 (1.0) | 40 (1.5) | 0.70 (0.30–1.65) | 0.41 | 0.78 (0.35–1.74) | 0.55 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 20 (3.5) | 85 (3.2) | 1.10 (0.68–1.79) | 0.71 | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.14 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 15 (2.6) | 57 (2.1) | 1.23 (0.70–2.18) | 0.47 | 1.48 (0.90–2.46) | 0.12 |

Data are n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Italic values are statistically significant.

aMajor adverse cardiac events is a composite of all-cause death, any myocardial infarction, emergent coronary artery bypass surgery, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization.

bTarget vessel failure is a composite of cardiac death, target vessel–related myocardial infarction, and clinically indicated target vessel revascularization.

cAt 30-days, no multivariable analysis was performed as the number of events was low.

The present analysis assessed PCI-naïve patients who underwent PCI for their first MI. We did this focus on patients without any previous coronary revascularization, as before laboratory tests for measuring troponin levels became generally available and applied, some PCI patients treated for non–ST-segment elevation MI, according to current definitions, were (falsely) classified as unstable angina. If such patients develop another MI later on, they might be considered as having their first MI and being premature CAD patients. To prevent such error that could have clouded the findings of our analysis, we considered only patients without previous PCI.

Risk factors

Differences in risk profiles have been reported when comparing MI patients with premature and non-premature CAD. Patients with premature CAD were more often men and obese, and they had a lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension.22–25 In addition, patients with premature CAD more often had a family history of (premature) CAD, suffered from dyslipidaemia or hypercholesterolaemia, and were smokers.22–25 The results of the present analysis in patients presenting with a first acute MI confirmed most of the previous findings. The prevalence of diabetes and hypertension was lower, while more premature CAD patients had a family history of CAD. Furthermore, in accordance with the literature, we found in patients with premature CAD a higher rate of current smokers and, on average, a higher body mass index. Yet, between patients with premature and non-premature CAD of our analysis, there was no difference in sex or hypercholesterolaemia. In this context, dissimilarities in the genetic and socio-cultural background of study populations from different countries and even continents may have played a role.

Outcome

A few previous studies evaluated the clinical outcome of young patients with MI. One study that compared the outcome between MI patients younger than 40 years and MI patients aged 41–50 years revealed no difference in 1-year outcome and long-term mortality,4 while most other researchers found patients with premature CAD to have lower adverse event rates.8,11,12,26 A study in patients who required PCI found the 6-month and 1-year mortality rates to be lower in premature CAD patients.12 In addition, a study in MI patients found lower 2-year rates for all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death in patients aged <45 years.26 In the current analysis, premature CAD was associated with lower 2-year rates of MACE and both all-cause and cardiac mortalities.

The findings of observational studies were similar to the results of the controlled clinical studies, showing lower mortality rates in patients with premature CAD.8,11 For instance, the prospective Dresden Myocardial Infarction Registry, which compared patients aged <40 years with older patients, observed lower in-hospital and 2-year mortality rates in the younger patient group.8 During follow-up of 2.4 years, the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry, which compared young MI patients <45 years with MI patients aged between 45 and 59 years, found a lower risk of all-cause mortality in the young patient group, but there was no statistically significant between-group difference in non-fatal stroke and MI.11 Considering the overall higher life expectancy of young individuals, the lower (all-cause and cardiac) mortality rates in young individuals with premature CAD do not surprise.

Limitations

The result of the present analysis might be transferred to a non-randomized setting as the current study was performed with data of four trials with broad inclusion criteria that aimed at replicating day-to-day clinical practice. Yet, this study has some limitations. The findings of this post hoc analysis of patient-level pooled data from four large-scale randomized all-comer trials should be considered hypothesis generating. In addition, as in most studies, we cannot exclude the presence of undetected or unmeasured confounders. As in the present analysis, the number of adverse events is relatively low, the impact of some risk factors may be overestimated, and the difference between the two groups might partly be explained by chance. In addition, in the present analysis overfitting may have occurred for the model, as too many variables may have been included, and some variables may not be validated in previous data sets but entered by chance. The study’s focus on PCI patients with a first MI ‘but no previous coronary revascularization’ might have resulted in the exclusion of some non-premature MI patients with extensive atherosclerotic burden. Yet, the criterion above was prudently chosen in order to prevent that patients of an older age, who previously met the criteria of premature CAD, might accidentally be classified as non-premature CAD. Better outcome found with new-generation DES might have resulted from a combination of refinement of DES, use of advanced interventional devices, refined concomitant pharmacological therapy, and increased awareness of and more aggressive goals for secondary prevention. In addition, detailed information about risk factors, co-morbidities, and medical therapy other than anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs were collected at the time of study enrolment only. For that reason, the impact of secondary prevention could not be assessed.

Conclusion

First MI patients with premature CAD, treated with contemporary stents, showed lower rates of MACE and all-cause mortality than those with non-premature CAD, which is most likely related to differences in cardiovascular risk profile. Patients with premature CAD were (by definition) younger and had lower rates of diabetes, hypertension, renal failure, and peripheral arterial disease than non-premature CAD patients. Yet, the premature CAD patients had more often a positive family history for CAD and were more often current smokers and overweight. Our findings suggest that in patients with a family history of (premature) CAD, it may be particularly useful to address these modifiable risk factors.

Funding

The present analysis was not externally funded. The TWENTE I trials was funded by Abbott Vascular and Medtronic. The DUTCH PEERS was funded by Boston Scientific Corporation and Medtronic. The BIO-RESORT trial was equally funded by Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. The BIONYX trial was equally funded by Biotronik and Medtronic.

Data availability

Given the privacy of the participants, data will not be shared publically. Researchers with a specific research question can send it to the corresponding author. The request will be assessed individually by a group of searchers consisting of members of the steering committees of the original trials.

References

Author notes

Conflict of interest: C.v.B. reports that the research department of Thoraxcentrum Twente has received research grants provided by Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. R.L.A. reports a teaching grant from Biotronik, a license from Sanofi, a speaking fee from Abiomed and support from Amgen for attending a meeting, all outside the submitted work. All other authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

- myocardial infarction, acute

- myocardial infarction

- stents

- coronary artery bypass surgery

- coronary arteriosclerosis

- coronary revascularization

- heart disease risk factors

- cardiac event

- follow-up

- peer group

- mortality

- treatment outcome

- drug-eluting stents

- revascularization

- premature coronary artery disease

Comments