-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Xavier Bossuyt, DFS70 Autoantibodies: Clinical Utility in Antinuclear Antibody Testing, Clinical Chemistry, Volume 70, Issue 2, February 2024, Pages 374–381, https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvad181

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Screening for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) on HEp-2 cells is helpful for the diagnosis and classification of ANA-associated rheumatic diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease, systemic sclerosis, and inflammatory myopathies. The dense fine speckled (DFS) pattern is a special HEp-2 IIF pattern (produced by anti-DFS70 antibodies) because it is not associated with a specific medical condition and therefore can obfuscate interpretation.

In this paper, detection methods for and clinical associations of anti-DFS70 antibodies are reviewed.

The target antigen of the antibodies that cause the DFS pattern is a 70 kDa protein (DFS70). Commercial methods that detect antibodies to full-length or truncated DFS70 are available for use in clinical laboratories (ELISA, chemiluminescence, dot/line blot). Anti-DFS70 can be found in (apparently) healthy individuals (with a higher frequency in young individuals and in females), in several (inflammatory) conditions and in malignancy. There is no clinical association that is well-established. Special attention (and critical reflection) is given to the observation that monospecific anti-DFS70 (i.e., in the absence of antibodies that are linked to ANA-associated rheumatic diseases) is rarely found in ANA-associated rheumatic diseases.

Introduction: Clinical Context

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are helpful laboratory markers to support the diagnosis of ANA-associated rheumatic diseases (AARD), including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren syndrome (SS), systemic sclerosis (SSc), mixed connective tissue disease, and inflammatory myopathies (IIM) [reviewed in (1)]. Classically, ANA are screened for by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) using human epithelial cells (HEp-2 IIF). If there is a positive signal, the titer and pattern are reported. The main clinically relevant nuclear patterns include centromere, homogeneous, speckled, and nucleolar patterns; the main cytoplasmic patterns include (fine) speckled and reticular patterns (1). The centromere pattern is highly associated with anticentromere protein B antibodies. Other patterns are also associated with certain antibodies, albeit it to a lesser extent than the centromere pattern. The homogeneous pattern is associated with antidouble stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies, the nuclear speckled pattern with antibodies to Sjögren syndrome antigen A2 (SSA), Sjögren syndrome type B antigen (SSB), U1-small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (RNP), Smith (Sm), Mi-2 autoantigen, ribonucleid acid RNA polymerase-III, Ku antigen, RuvBL1/2 autoantigens, the nucleolar pattern with antibodies to fibrillarin, polymyositis/scleroderma (PM-Scl) autoantigen, Th/To autoantigen, the cytoplasmic (fine) speckled pattern with antisynthetase antibodies, antiribosomal-P and antisignal recognition particle, and the cytoplasmic reticular pattern with antimitochondrial antibodies (1). If there is a positive HEp-2 IIF result, specific antibodies are searched for. Specific antibodies have a high clinical relevance as they are associated with particular diseases, such as anti-dsDNA, anti-SSA and antiribosomal-P with SLE, anti-SSA and anti-SSB with SS, anti-U1-RNP with mixed connective tissue disease, anti-CENP-B, antiscl-70, antipolymerase-III, antipolymyositis/scleroderma and antifibrillarin with SSc, antisynthetase and anti-Mi-2 with IIM, and anti-Ku and anti-RuvBL1/2 with overlap syndromes (1).

There is a particular HEp-2 IIF pattern, the dense fine speckled (DFS) pattern (associated with antibodies to DFS70), that cannot be linked to a specific disease and that can therefore complicate interpretation of HEp-2 IIF results. In this paper (a narrative mini-review), the current understanding of DFS70 autoantibodies in clinical ANA testing is reviewed.

The DFS70 Autoantigen

The DFS pattern was first described in 1994 in individuals with interstitial cystitis (2). As the antibodies reacted with a 70 kilodalton (kDa) protein in western blot, the target antigen was termed DFS70 (2, 3). Immunoscreening of a complementary DNA (cDNA) library using serum from a patient with atopic dermatitis showed that the cDNA encoding DFS70 was identical to a transcription coactivator called p75, which is required for RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription (3, 4). In that study, antibodies to DFS70 were found in sera from patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma, and interstitial cystitis (3). Singh et al. identified and isolated lens epithelium-derived growth factor of 75 kD (LEDGF/p75) from a lens epithelial cell library by immunoscreening with serum from a patient with age-related cataract (5, 6). DFS70, transcription coactivator p75, and LEDGF/p75 share identical amino acid sequences and are the same protein.

LEDGF/p75 is a DNA-binding polypeptide that acts as a (stress-activated) transcriptional coactivator (4, 6, 7). It is assumed that cellular stress upregulates LEDGF/p75, which will then reinforce a cellular protective response against stress [reviewed in (8)].

LEDGF/p75 plays an important role in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-biology. It is the host protein that is used by HIV as a co-factor for HIV-integrase and is crucial for the integration of the viral genome into the host chromatin (9). It is also a stress oncoprotein that is upregulated in cancers. Elevated LEDGF/p75 transcript expression has been reported in prostate, colon, thyroid, and breast cancers, and elevated protein expression in prostate, colon, thyroid, liver, and uterine tumors (10).

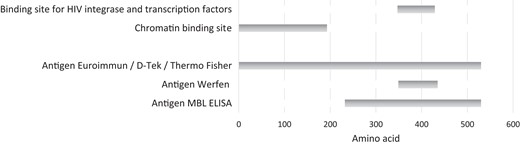

LEDGF/p75 is a 530 amino acid (aa) long protein. The N-terminal PWWP (defined by Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro motif/Pro: proline, Trp: tryptophan) domain (aa 1–93) is critical for chromatin binding. The C-terminal integrase binding domain domain (aa 347–429) is the binding site for the HIV-1 integrase and transcription factors linked to cell survival signaling and oncogenesis [reviewed in (8)] and corresponds to the epitope of the autoantibodies (11). Figure 1 shows the LEDGF/p75 (DFS70) domains and the DFS70 antigens used in commercial assays.

Domains in LEDGF/p75 (DFS70) and DFS70 antigens used in commercial assays.

The gene name of DFS70, LEDGF/p75 or transcriptional coactivator p75/p52 is PSIP1 and the protein name recommended by Uniprot is “PC4 and SRSF1-interacting protein” (12). Proprotein convertase 4 (PC4) is a transcription coactivator component of RNA pol II complex and serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) is involved in splicing (7).

Detection of Anti-DFS70 Antibodies

DFS70 Pattern by HEp-2 Immunofluorescence

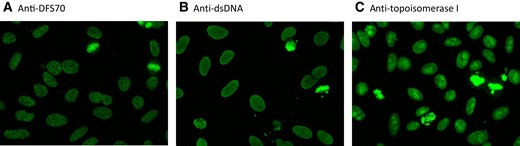

The DFS HEp-2 cell IIF pattern is described by International Consensus on Antinuclear Antibody (ANA) Patterns (ICAP) as follows: “Speckled pattern distributed throughout the interphase nucleus with characteristic heterogeneity in the size, brightness, and distribution of the speckles. Throughout the interphase nucleus, there are some denser and looser areas of speckles (very characteristic feature). The metaphase plate depicts strong speckled pattern with some coarse speckles standing out.” (13). The DFS pattern is coded as Anti-Cell 2 (AC-2) pattern by ICAP. Even though the description of the pattern by ICAP is evocative, detection of the DFS pattern can be difficult, especially if the technologist is not well-habituated with the pattern. An internet-based survey to assess how accurately the DFS IIF pattern was recognized by technologists (n = 230) revealed that the AC-2 DFS IFA pattern was difficult to detect (correct identification by roughly 50% of respondents), particularly when other ANA patterns co-occurred in the same serum sample (correct identification by roughly 10% of respondents) (14). Figure 2 exemplifies the DFS IIF pattern (Fig. 2A) as well as the pattern associated with anti-dsDNA (Fig. 2B) and antitopoisomerase I (Fig. 2C) antibodies.

IIF of selected samples. IIF images of sera with anti-DFS70 antibodies (A), anti-dsDNA antibodies (B), and antitopoisomerase antibodies (C). The IIF substrate used was NOVA Lite DAPI ANA Kit, Werfen) on NOVA View (Werfen). The assay for anti- DFS70/LEDGFp75 antibodies was QUANTA-Flash DFS70 CLIA.

The typical DFS IIF pattern is best observed in cases of monospecific anti-DFS70. The pattern is much less clear when other antibodies (which can mask the anti-DFS70 antibodies) are also present (concomitant presence of several ANAs) (15). Differences in DFS detection between commercial HEp-2 assays have been described (15).

Modifications of the HEp-2 assay have been developed to eliminate interference of anti-DFS70 antibodies. IMMCO Diagnostics developed a modified HEp-2 assay that uses PSIP1−/− HEp-2 cells that do not express the 70 kDa protein (HEp-2 ELITE DFS70-knock out substrate). These cells detect all nuclear antibodies except anti-DFS70. Werfen offers a variation of the HEp-2 assay in which immunoabsorption of sera against recombinant DFS70/LEDGF protein is performed (NOVA Lite HEp-2 Select, Werfen).

Antibodies that produce a HEp-2 IFA pattern that resembles the genuine DFS pattern but that do not react with DFS70/LEDGFp75 have been described (16). Antibodies that generate such a “DFS-like” or “pseudo-DFS” IFA pattern have been reported to produce weaker metaphase staining and less heterogeneous fine speckles (17). Attempts to identify the target antigens of the pseudo-DFS or DFS-like pattern have been unsuccessful so far (16, 18). Given the subjectivity of HEp-2 IFA, the difficulty of correctly identifying the DFS70 pattern and the existence of pseudo-DFS autoantibodies, confirmatory testing by a solid phase assay (e.g., an ELISA) is recommended when a presumed DFS HEp-2 IIF pattern is found in a clinical setting. Future studies are needed to define the potential diagnostic utility and the target antigens of the pseudo-DFS pattern.

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies by Solid Phase Assays

Several commercial immunoassay platforms for detection of anti-DFS70 antibodies are available. The nature of the antigen (truncated vs full-length) might differ between assays (Fig. 1). The antigen used in the CLIA (QUANTA-Flash DFS70, Werfen) (first commercial assay) consists of a recombinant DFS70 fragment expressed in Escherichia coli, spanning from amino acid 349 to 435. The antigen used in the fluoroenzyme immunoassay from Thermo Fisher (EliA DFS70) is a full-length human DFS70 antigen expressed in an insect cell/baculovirus system. The antigen used in the ELISA from Euroimmun is human full-length recombinant DFS70 expressed in mammalian cells, whereas the ELISA from MBL uses antigen from an insect cell expression system into which cDNA encoding the region from amino acid 232 to 530 has been inserted (19). The DFS70 antigen used in the D-Tek dot blot method and the Euroimmun line blot method is full-length (aa 1–530) recombinant protein.

Although concordance between assays is high, (small) differences between assays that use full-length and truncated antigen have been described (20, 21). Cutoffs proposed by the manufacturer might be suboptimal and should be locally verified and adjusted (22, 23). A study that compared 6 different assays concluded that there is substantial interassay variability between commercially available assays. The most concordant results have been found with CLIA, MBL-ELISA, and Euroimmun line blot assays (23).

A reference anti-DFS70 standard is available through the Autoantibody Standardization Committee (www.autoab.org), which is part of the International Union of Immunology Societies (24). The standard has been developed based on stepwise controlled pooling of serum samples from hundreds of individuals with anti-DFS70 antibodies (24). The standard can be useful for assay validation and/or for interpretation of (education on) the DFS70 pattern (24).

Clinical Conditions in Which Anti-DFS70 Antibodies Have Been Described

Initial studies identified anti-DFS70 antibodies in interstitial cystitis and atopic dermatitis (2, 3). Since then, many studies have reported anti-DFS70 antibodies in various conditions. Previous review papers have extensively summarized literature on clinical associations of anti-DFS70 antibodies. We refer to these reviews (that contain summary tables) (8, 25) for more information. None of the clinical associations is generally accepted or clinically used. Early studies need to be corroborated (in multicenter, international studies) using validated assays to definitively document clinical associations (7).

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in Inflammatory Conditions

The conditions in which anti-DFS70 antibodies have been described include various inflammatory diseases. Studies suggest associations with eye diseases (cataract, atypical retinal degeneration), atopic diseases (dermatitis), skin diseases (alopecia), thyroiditis, and systemic rheumatic diseases (see next) [reviewed in (7, 8, 25)]. A cytotoxic effect of anti-DFS70 on lens epithelial cells in patients with atopic dermatitis has been suggested (26).

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in Malignancy

Some studies found anti-DFS70 antibodies in malignant diseases, mainly prostate cancer, whereas other studies reported no increased prevalence of anti-DFS70 in malignant disease [recently reviewed in (7)]. Thus, the question whether there is an increased prevalence of anti-DFS70 in malignancy remains unsettled.

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in a Routine Cohort of Patients Tested for ANA

Duran et al. recently documented the clinical conditions of 281 individuals with a DFS70 pattern on HEp-2 IIF (HEp-2010, Euroimmun) confirmed by line blot (Euroimmun) (27). In this study, 61% of the individuals had no specific diagnosis, 15.3% had a rheumatologic disease, 10% an allergic disease, 5% a hematological abnormality, 3.6% a thyroid disease, 1.8% a gastroenterological disease, 1.4% malignancy, and 1.1% an infection (27). This illustrates that anti-DFS70 antibodies can be found in various medical conditions.

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in Apparently Healthy Individuals and in the General Population

In a study in which sera from healthy blood donors (n ≥ 300 per site) was collected in 7 countries (USA, Italy, Spain, Germany, UK, Belgium, Brazil), the prevalence of anti-DFS70 (measured by CLIA) varied from 1.2% (Italy) to 8.5% (USA) (28). Overall, the prevalence was higher in young blood donors (<35 years old; 5% vs 2.7%) and among females (4.5% vs 3%) (28).

Analysis of anti-DFS70 antibodies in a civilian noninstitutionalized US population (n = 13 519) sampled from 3 time periods (1988–1991/1999–2004/2011–2012) showed that: (a) women were more likely than men, black people less likely than white people, and active smokers less likely than nonsmokers to have anti-DFS70 antibodies; and (b) the prevalence of anti-DFS70 antibodies increased from 1.6% in 1988–1991 to 4.0% in 2011–2012 (18). In this study, age was not associated with anti-DFS70 antibodies (18). ANA-positive samples with the AC-2 pattern were tested for anti-DFS70 antibodies by MBL-ELISA (18).

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies and Environmental Exposure

Tobacco smoke exposure is negatively associated with anti-DFS70 antibodies and an increase in prevalence of anti-DFS70 antibodies has been noticed over a 25-year time period (18). This might point toward environmental factors affecting anti-DFS70 antibody induction.

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in Systemic Rheumatic Diseases

In early studies, it was reported that anti-DFS70 antibody positivity was more prevalent in healthy individuals than in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Consequently, it was considered that anti-DFS70 antibodies could be used to rule out systemic autoimmune diseases in ANA-positive persons.

Watanabe et al. (29) reported that 11% of 597 healthy individuals working in a hospital (142 men, 455 women) tested positive for anti-DFS70 (tested by home-made ELISA), which was higher than the prevalence (1.5%) of anti-DFS70 in 200 individuals with various systemic rheumatic diseases [2% in SLE, 7% in SS, 0% in SSc, IIM and rheumatoid arthritis (RA)].

Mahler et al. (30) reported that the prevalence of anti-DFS70 (tested by CLIA) was significantly higher in apparently healthy individuals (8.9%) than in different pathologies including SLE (2.8%), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (6%), interstitial cystitis (5%), asthma (4%), RA (2.8%), Grave’s disease (1.7%), malignancy (0%), atopic disease (0%), SS (0%) infections (0%), and multiple sclerosis (0%).

Mariz et al. (31) found the DFS pattern by HEp-2 IIF in healthy individuals (39/918) (4.2%) but not in individuals with an autoimmune rheumatic disease (n = 153). They also reported that the nuclear HEp-2 IIF DFS pattern in healthy individuals tended to appear at high titer and to be stable over the years (retested after a period of 3.6–5 years) (31). The authors suggested that the DFS pattern enhanced the ability to discriminate ANA-positive healthy individuals from patients with AARDs.

When more studies became available, it became apparent that study outcomes were not consistent between studies and it emerged that the difference in occurrence of anti-DFS70 antibodies between healthy individuals and individuals with systemic rheumatic diseases might not be as pronounced as initially found (7). The idea that the prevalence of anti-DFS70 antibodies in systemic rheumatic diseases is lower than the prevalence in healthy individuals has been questioned (7). A distinctive feature that emerged, however, was that the prevalence of monospecific anti-DFS70 (i.e., anti-DFS70 in the absence of other disease-specific/associated ANA) is considered more prevalent in healthy individuals than in AARD.

In 2017, Conrad et al. (25) summarized published studies available at that time and reported an overall prevalence of anti-DFS70 antibodies in systemic rheumatic diseases (AARD and RA) of 2.8% (frequency of monospecific anti-DFS70: 0.5%). The prevalence was 0.8% in RA (n = 122; 0% monospecific), 2.7% in SLE (n = 1396; 0.7% monospecific), 1.5% in SSc (n = 331, 0% monospecific), 9.7% in SS (n = 144; 1% monospecific), and 3.5% in IIM (n = 231, 0.9% monospecific). The frequency of anti-DFS70 antibodies in apparently healthy individuals varied between 0% and 21.6%, with a median/mean frequency of 5.5%/6.8% (25).

Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in SLE

In an international SLE inception cohort (SLICC), the frequency of anti-DFS70 (tested by CLIA) was 7.1% (15). SLE patients with musculoskeletal activity or with anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 were more likely and SLE patients with anti-dsDNA or anti-SSB/La were less likely to have anti-DFS70 (15). In a Chinese study, the prevalence of anti-DFS70 was higher in SLE (20.7%) than in healthy individuals (9.5%) and other systemic rheumatic diseases (10.8%) (tested by in-house ELISA) (32). Anti-DFS70 antibodies were associated with anti-dsDNA, proliferative lupus nephritis, and renal activity index (32, 33). The inconsistencies between the Chinese study and the study on the SLICC cohort need to be clarified in future studies. It will be important to address whether there are ethnic differences in anti-DFS70 expression in SLE.

Monospecific Anti-DFS70 in AARD

Several studies indicate that while the overall prevalence of anti-DFS70 might be comparable between healthy individuals and individuals with systemic rheumatic diseases, the prevalence of monospecific anti-DFS70 is lower in systemic rheumatic diseases than in healthy individuals (19, 20, 34–39). Based on such studies (summarized in Table 1) it has been proposed that monospecific anti-DFS70 is useful in excluding AARD.

Summaries of studies on monospecific anti-DFS70 in systemic rheumatic diseases.

|

|

Summaries of studies on monospecific anti-DFS70 in systemic rheumatic diseases.

|

|

The conclusions drawn from different studies vary. Some investigators stress that monospecific anti-DFS70 has the potential to distinguish individuals with AARD from ANA-positive individuals with non-AARD conditions or healthy individuals and argue that monospecific anti-DFS70 autoantibodies should not be considered as a criterion for classification or diagnosis (15). Other investigators note that the presence of monospecific anti-DFS70 antibodies does not exclude AARD with certainty and suggest that it is the absence of AARD-associated ANA and clinical symptoms that contribute to the exclusion of AARD rather than the presence of anti-DFS70 (20). Still other investigators stress that disease-associated antibodies may be hidden behind a DFS HEp-2 IIF pattern and argue that specific tests to detect CTD-related autoantibodies should be performed instead of anti-DFS70 confirmation tests when a DFS pattern is observed by HEp-2 IIF (40, 41). Kang et al. (40) reported that among cases with the DFS IIF pattern, 68% had anti-DFS70 antibodies and 11.5% had CTD-related autoantibodies.

As it is apparent that the prevalence of monospecific anti-DFS70 in AARD is lower than the prevalence of anti-DFS70 in AARD it would be interesting to evaluate the prevalence of monospecific anti-DFS70 in AARD patients that lack AARD-specific/associated antibodies. Such information could further advance our understanding of the clinical value of monospecific anti-DFS70 in ruling out AARD.

Anti-DFS70 in Clinical Routine Antinuclear Antibody Testing

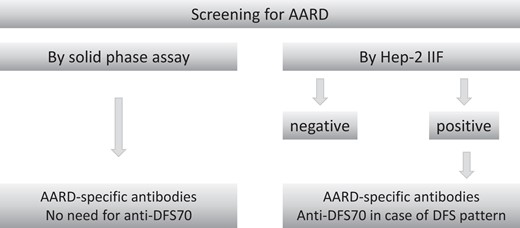

The indications for anti-DFS70 testing in clinical laboratories may depend on the setting, the experience of the laboratory with HEp-2 IIF, the diagnostic strategies used, and the individual situation of the patient. Hereunder, some scenarios are considered (Fig. 3).

Strategies for anti-DFS70 antibody detection in a clinical laboratory.

Testing for Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in Isolation

As there is no established, widely confirmed association of anti-DFS70 antibodies with a particular medical condition, testing for anti-DFS70 antibodies in isolation is not recommended.

Testing for Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in Context of AARD Screening by Solid Phase Assays

If AARD are screened for by specific (solid phase) assays, there is no need to include anti-DFS70 (as anti-DFS70 is not associated with a particular AARD).

Testing for Anti-DFS70 Antibodies in Context of AARD Screening by HEp-2 IIF

If HEp-2 IIF reveals a positive result, AARD-specific/associated autoantibodies should be identified by solid phase assays. If no AARD-specific/associated antibodies are identified and HEp-2 IIF reveals a (pseudo) DFS pattern or an alike pattern, monospecific anti-DFS70 antibodies can be confirmed by a specific assay. This will help to accurately identify anti-DFS70 antibodies and to clarify the observed HEp-2 IIF pattern.

There is no international consensus on which specific antibodies should be tested to define “monospecificity” of anti-DFS70. The most prevalent AARD-specific/associated antibodies (dsDNA, SSA, SSB, U1-RNP, Sm, Jo-1, anticentromere protein B, Scl-70) should be considered, but the optimal set of antibodies to be tested is situation-dependent. For example, in case of a clinical suspicion of IIM, myositis-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-MDA-5, Mi-2, TIF-1γ, NXP-2, SAE, SRP, HMGCR, and antisynthetase antibodies) should be considered and in case of a clinical suspicion of SSc, SSc-specific antibodies should be considered.

Taken together, in the presence of anti-DFS70 antibodies, exclusion of AARD should be based on absence of AARD-specific/associated antibodies and clinical presentation. Monospecific anti-DFS70 is infrequently found in AARD (+/−1% of cases).

Conclusion

Laboratories that screen ANA by HEp-2 IIF should be proficient in recognition of the DFS pattern. Solid phase assays should be used to verify that anti-DFS70 antibodies underlie the DFS pattern. Anti-DFS70 antibodies can be found in (apparently) healthy individuals with a higher frequency in young individuals and in females, in various (inflammatory) conditions and in malignancy. There is no clinical association that is well-established and confirmed in different studies. Because monospecific anti-DFS70 is rarely found in AARD, it has been proposed that monospecific anti-DFS70 (i.e., anti-DFS70 in the absence of AARD-specific/associated antibodies) is helpful in ruling out AARD. The absence of AARD-specific antibodies is probably the main driver of this negative association. Despite the many studies that have been performed on anti-DFS70 antibodies there is still a need to better understand the clinical associations, the changes over time of the antibody levels, the pathogenic and/or protective role of the antibodies and the factors (geographic, ethnic, age, sex, environmental) that may affect antibody expression. Cutoff values of commercially available solid phase assays for anti-DFS70 antibodies should be aligned and the target antigens and clinical associations of the pseudo-DFS pattern need to be defined.

Nonstandard Abbreviations

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; DFS, dense fine speckled; AARD, ANA-associated rheumatic diseases; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SS, Sjögren syndrome; SSc, systemic sclerosis; IIM, inflammatory myopathies; HEp-2, human epithelial; dsDNA, double stranded DNA; SSA, Sjögren syndrome antigen A2; SSB, Sjögren syndrome type B antigen; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; Sm, Smith; cDNA, complementary DNA; LEDGF/p75, lens epithelium-derived growth factor of 75 kD; ICAP, International Consensus on Antinuclear Antibody Patterns.

Author Contributions

The corresponding author takes full responsibility that all authors on this publication have met the following required criteria of eligibility for authorship: (a) significant contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (b) drafting or revising the article for intellectual content; (c) final approval of the published article; and (d) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the article thus ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the article are appropriately investigated and resolved. Nobody who qualifies for authorship has been omitted from the list.

Authors’ Disclosures or Potential Conflicts of Interest

Upon manuscript submission, all authors completed the author disclosure form.

Research Funding

None declared.

Disclosures

X. Bossuyt reports consultancy and/or speakers fees from Werfen and Thermo Fisher Scientific and has filed a patent for detection of anti-THO autoantibodies.

References

UniProt. O75475·PSIP1_HUMAN function.

ICAP. AC-2 – Nuclear dense fine speckled.

(Accessed 25 April 2023).