-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alireza Haghighi, Mohamed Al-Hamed, Safa Al-Hissi, Ann-Marie Hynes, Maryam Sharifian, Jamshid Roozbeh, Nasrollah Saleh-Gohari, John A. Sayer, Senior-Loken syndrome secondary to NPHP5/IQCB1 mutation in an Iranian family, NDT Plus, Volume 4, Issue 6, December 2011, Pages 421–423, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndtplus/sfr096

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Senior-Loken syndrome (SLS) is a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by nephronophthisis and early-onset retinal degeneration. We used a large Iranian family with SLS to establish a molecular genetic diagnosis. Following clinical evaluation, we undertook homozygosity mapping in two affected family members and mutational analysis in known SLS genes coinciding with regions of homozygosity. In a region of homozygosity coinciding with a known SLS locus on chromosome 3q21.1, we found a homozygous non-sense mutation R332X in NPHP5/IQCB1. This is the first report of a molecular genetic diagnosis in an Iranian kindred with SLS.

Background

Senior-Loken syndrome (SLS) is a rare renal ocular condition with autosomal recessive inheritance [1,2]. The main features of this disease include nephronophthisis (NPHP) leading to end-stage renal failure and early-onset retinal degeneration [3]. Recent molecular genetics have identified mutations in several NPHP genes that lead to SLS. Mutations in genes NPHP1-6 and NPHP10 (alias SDCCAG8) have been associated with disease variants SLS Types 1–7, respectively [4–10].

Case report

We identified an extended consanguineous family with five affected members with SLS. The family was from Iran with a Persian ethnical background. The male proband presented at the age of 26 years with established renal failure and blindness. He was born to consanguineous (first cousins) parents. His health was relatively normal until his teenage years, when his vision started deteriorating. He became almost blind by the age of 17 years. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed retinitis pigmentosa and cataracts. Reviewing his presentation, his family reported a longstanding history (since childhood) of polyuria and polydipsia. At the age of 18 years, he developed lower limb oedema. Laboratory investigations confirmed advanced renal failure (serum creatinine; 11.3 mg/dL). On ultrasonography of the abdomen, both kidneys were of normal size with a hyperechogenic cortex and mild hydronephrosis. There was a 28-mm small cyst in the upper pole of the right kidney. A percutaneous renal biopsy showed medullary cystic changes and was consistent with a diagnosis of NPHP. He subsequently underwent successful renal transplantation.

Other family members were similarly affected. The proband’s elder sister and one of his younger brothers were also affected by SLS (see Figure 1). The proband’s elder sister presented with decreased vision during her teenage years that resulted in complete blindness at 20 years of age. She developed severe peripheral oedema at 26 years of age and died due to complications of end-stage renal failure. The proband’s younger brother became blind at 17 years of age and end-stage renal failure occurred 2 years later. He underwent renal transplantation and is currently in good health.

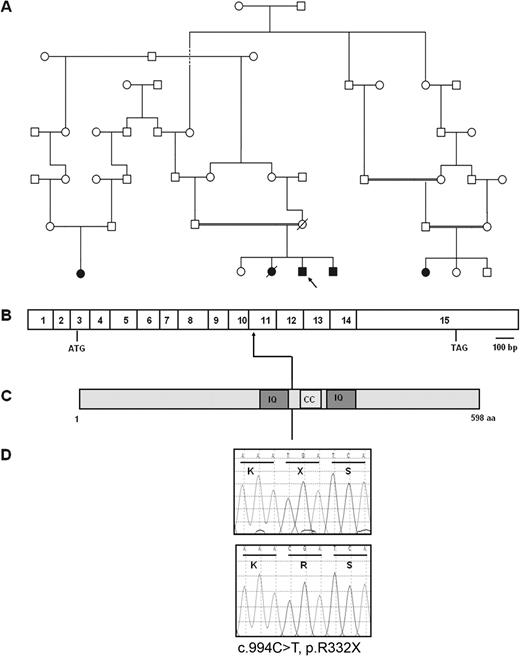

Molecular genetic diagnosis of NPHP5/IQCB1 mutation in a consanguineous Iranian family with SLS. (A) The consanguineous Iranian pedigree with SLS is shown. Circles represent females, whereas squares represent males. The index case is arrowed. Filled symbols denote presence of SLS. (B) Exon structure of NPHP5/IQCB1 drawn relative to scale bar with ATG start codon and TAG stop codon marked. (C) Representation of protein motifs of nephrocystin-5 with predicted protein domains IQ and coiled-coil (marked CC). (D) Sequence traces (nucleotides and respective codons) are shown for affected individuals (top) and healthy controls (bottom). The homozygous mutation c.994C>T results in the non-sense mutation p.R332X.

Genetic analysis was performed in this family in order to obtain a molecular diagnosis and to allow for screening of siblings and other family members. Genetic analysis was performed in two affected siblings and both parents. To identify chromosome aberrations and regions of homozygosity and the likely disease locus within this consanguineous family, we carried out a genome-wide scan search using Affymetrix Cytogenetics Whole-Genome 2.7M Arrays (http://www.affymetrix.com). The data were analysed using the Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) software. A region of homozygosity on chromosome 3q21.1 that contained the NPHP5/IQCB1 gene was noted. This gene was screened by direct sequencing of polymerase chain reaction products of coding regions.

In Exon 11 of the NPHP5/IQCB1 gene, we found a known mutation c.994C>T predicted to cause a truncating mutation p.R332X within the IQ motif containing protein B1 (alias nephrocystin-5) [8]. The affected siblings were (as expected) homozygous for the mutation (Figure 1), while both parents were heterozygous for the mutation. The unaffected sibling was homozygous for the wild-type allele.

Discussion

The proband was diagnosed with SLS, based on end-stage renal failure and retinitis pigmentosa, that resulted in blindness in the second decade of life. The renal biopsy confirmed nephronophthisis with medullary cyst formation. Other members of the extended family had presented with similar clinical features consistent with SLS and clinical details have been previously reported [11]. This is the first SLS kindred from Iran where a molecular diagnosis has been established.

The identified mutation c.994C>T, p.R332X in NPHP5/IQCB1 has been previously reported in other kindreds with SLS [8]. Otto et al. [8] reported two families with SLS from Italy and Germany who had children with the p.R332X mutation. Reviewing their clinical details, the Italian child presented with retinitis pigmentosa before 6 months of age, whereas the onset age of retinitis pigementosa for the German patient was unknown, while end-stage renal failure occurred at 9 and <13 years of age, respectively [8]. In the Iranian family we report, both retinal and renal features had a delayed age of onset in comparison. These differences highlight the variable onset of disease for this particular mutation. Other families with NPHP5/IQCB1 mutations originated from Turkey, Germany, North Africa, Belgium and Switzerland and all had a retinal renal phenotype [8].

In a worldwide cohort of patients with NPHP, NPHP5/IQCB1 mutations account for ∼3% of cases [12]. However, NPHP5/IQCB1 mutations may be a common cause of SLS, given that all reported individuals with a mutation in this gene displayed retinitis pigmentosa [8]. The subcellular localization of the nephrocystin-5 protein to the connecting cilium of the photoreceptor cells and the primary cilium of renal epithelial cells [8] implicates this protein as a key regulator of ciliary function.

We thank Marziye Mohamadi Anaie for assistance with DNA extraction. A.-M.H is funded by Newcastle Hospitals Charities and the Northern Counties Kidney Research Fund. J.A.S. is a GlaxoSmithKline clinician scientist.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Comments