-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David P Serota, Tyler S Bartholomew, Hansel E Tookes, Evaluating Differences in Opioid and Stimulant Use-associated Infectious Disease Hospitalizations in Florida, 2016–2017, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 73, Issue 7, 1 October 2021, Pages e1649–e1657, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1278

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The opioid epidemic has led to increases in injection drug use (IDU)-associated infectious diseases; however, little is known about how more recent increases in stimulant use have affected the incidence and outcomes of hospitalizations for infections among people who inject drugs (PWID).

All hospitalizations of PWID for IDU-associated infections in Florida were identified using administrative diagnostic codes and were grouped by substance used (opioids, stimulants, or both) and site of infection. We evaluated the association between substance used and the outcomes: patient-directed discharge (PDD, or “against medical advice”) and in-hospital mortality.

There were 22 856 hospitalizations for infections among PWID. Opioid use was present in 73%, any stimulants in 43%, and stimulants-only in 27%. Skin and soft tissue infection was present in 50%, sepsis/bacteremia in 52%, osteomyelitis in 10%, and endocarditis in 10%. PWID using opioids/stimulants were youngest, most uninsured, and had the highest rates of endocarditis (16%) and hepatitis C (44%). Additionally, 25% of patients with opioid/stimulant use had PDD versus 12% for those using opioids-only. In adjusted models, opioid/stimulant use was associated with PDD compared to opioid-only use (aRR 1.28, 95% CI 1.17–1.40). Younger age and endocarditis were also associated with PDD. Compared to opioid-only use, stimulant-only use had higher risk of in-hospital mortality (aRR 1.26, 95% CI 1.03–1.46).

While opioid use contributed to most IDU-associated infections, many hospitalizations also involved stimulants. Increasing access to harm reduction interventions could help prevent these infections, while further research on the acute management of stimulant use disorder-associated infections is needed.

Increasing injection of opioids over the last decade has led to an epidemic of injection drug use (IDU)-associated infectious diseases, including increasing incidence of chronic viral infections (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] and hepatitis C virus [HCV]) [1–3] and invasive bacterial infections, such as skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI), endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis [4, 5]. Hospitalizations for IDU-associated infections are characterized by long lengths of stay [6], high readmission rates [7], increased patient-directed discharge (PDD, also known as “against medical advice”) [6], and high intermediate to long-term mortality [8]. In a cohort of people who inject drugs (PWID) with IDU-associated endocarditis, 5-year mortality was 42% with median age of 37 years at the time of diagnosis [8]. Beyond the toll on the healthcare system and patient mortality, hospitalizations for IDU-associated infections are often traumatic experiences for PWID, characterized by stigmatization, untreated withdrawal, and undertreated pain [9]. Frequently, the underlying substance use disorder (SUD) goes untreated [10, 11], with only 6% of patients receiving life-saving medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) after a diagnosis of IDU-associated endocarditis [12]. This lack of SUD treatment contributes to posthospital mortality, which is most often due to overdose or recurrent or persistent infection [13].

To date, most discussion of IDU-associated infections has focused on infections due to opioid use disorder (OUD) or SUD in general. More recently, there has been recognition of rising rates of methamphetamine and cocaine use disorders (together, stimulant use disorder) and their involvement in drug-related mortality; the “fourth wave” of the United States (US) drug overdose crisis. Cocaine-associated overdoses among black men have neared the rate of opioid-related overdose among white men for many years, but has not garnered as much public attention [14]. Overdose deaths involving stimulants doubled between 2015 and 2017, with a majority also including opioids [15]. Among people presenting for SUD treatment there was a 70% increase in the rate of reporting methamphetamine use between 2010 and 2017 [16]. Little is known about how stimulant use or opioid/stimulant use (use of both opioids and stimulants) impact IDU-associated infectious disease incidence, presentation, and outcomes. Yet, emerging evidence identifies people with stimulant use and opioid/stimulant use as having distinct characteristics compared to those with opioid-only use that might impact infectious diseases among PWID [17–19]. People who overdosed with polysubstance by toxicology were more likely to have experienced homelessness and were more likely to be non-Hispanic black race; both are social determinants of health that can impact infection outcomes [18].

People with opioid/stimulant use and stimulant use may have different sociodemographic factors impacting their mortality, access to care, homelessness, and ability to engage in care. These factors could lead PWID who use stimulants to present later with more advanced and disseminated disease, such as endocarditis. Based on differences in frequency of injection, method of drug preparation, and pharmacology, stimulant use may predispose to different infectious syndromes and a potentially different spectrum of microbiology. Based on these factors, stimulant use is especially strongly associated with HIV and HCV infection [20]. Because no highly effective medication for stimulant use disorder exists, as it does for OUD, patients with stimulant use disorder require a unique approach to treatment. In order to understand how increasing stimulant use is contributing to the epidemic of IDU-associated infectious diseases, we evaluated all hospitalizations of PWID for IDU-associated infections in the state of Florida and compared characteristics between those with opioid, stimulant, and opioid/stimulant-associated infections. Because fewer effective treatments for stimulant use disorder exist, we hypothesized that hospitalizations for stimulant and opioid/stimulant-associated infections would result in more frequent patient-directed discharge. We also suspected that PWID using stimulants would have higher rates of endocarditis, a hallmark of advanced infection.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Data Source

This was a retrospective cohort study of PWID hospitalized with IDU-associated infections. Data were collected from the Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA) Hospital Inpatient Limited Data Set from the Florida Center for Health Information and Transparency. AHCA disclaims responsibility for analysis, interpretations, and conclusions.

AHCA collects administrative data on all hospitalizations in the state at public and private hospitals, excluding federal hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, and long-term acute care facilities. Data collected included demographic information, diagnostic codes using international classification of disease 10 (ICD-10), procedure codes, facility location, and discharge disposition. All personal identifiers were removed prior to data analysis. Because this study included the entire population of all PWID hospitalizations for infection in Florida, no sampling technique was used. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami (IRB 20191019).

Participants

PWID hospitalizations were identified out of the data set of all hospitalizations in the state of Florida. We defined “PWID” as a patient with an inpatient admission involving an ICD-10 drug use diagnosis code and an infection code typical of IDU-associated infections (bacteremia, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, or SSTI). Individual ICD-10 drug and infection codes can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Each hospitalization in Florida for a PWID with an IDU-associated infection was considered an individual case. We made the assumption that identification of a hospitalized PWID with SSTI, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, or bacteremia/sepsis was an injection-associated infection, based on studies validating this approach [21, 22]. The algorithm used in this study was previously validated externally [23] against a data set of known PWID in Canada [24]. Because data were deidentified, repeat hospitalizations for the same person were recorded as separate cases. For these analyses, only patients with opioid or stimulant use drug codes were included.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures for this study were patient-directed discharge (coded as “against medical advice” in the data set) and in-hospital mortality, both coded as binary outcomes. Both are mandatory measures reported in the limited AHCA dataset. Secondary outcomes examined were IDU-associated infectious diseases, including SSTI, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and bacteremia/sepsis, determined by ICD-10 codes (Supplementary Table 1).

Risk Factor Measures (or Covariate Measures)

Sociodemographic variables included age (categorized into 18–34, 35–54, 55–64, 65–75 years), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic), sex (male/female), insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, Private, Uninsured), length of hospital stay (in days), and hospital facility. Comorbidities were derived using ICD-10 codes adapted from the method created by Elixhauser and colleagues and can be found in Supplementary Table 1 [25]. The primary exposure of interest was substance used as defined by ICD-10 codes for opioid use, cocaine use, and amphetamine (including other stimulant/psychostimulant) use in Supplementary Table 1. Cases were classified into three categories; opioid-only use, stimulant-only use (either amphetamine or cocaine with no opioid use), and opioid/stimulant use (presenting with an opioid use code and a co-occurring stimulant use code).

Statistical Methods

Based on the validated algorithm, the cohort was compromised of all hospital admissions of PWID in Florida between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2017. Those who were diagnosed with “other psychoactive substance use” and no opioid or stimulant use codes were excluded. We described characteristics of the cohort, stratified by drug use category, using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and medians and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables.

Multivariable Poisson regression models were used to evaluate the association between substance use category and different types of infection. We estimated the adjusted relative risk (aRR) with 95% CI controlling for socio-demographics, HIV/HCV status, and comorbidities. To account for clustering at the hospital-level, we used a mixed-effects model with random intercept. Robust standard errors were calculated using an unstructured covariance matrix. Euler diagrams were generated to present the overlap in infectious sequelae within each drug category. Mixed-effects Poisson regression models were similarly used to examine the association between drug category and the outcomes of patient-directed discharge and in-hospital mortality, controlling for socio-demographics, HIV/HCV infection, comorbidities, and infection type. In the analysis for predictors of patient-directed discharge, people who died in the hospital were excluded. Due to the exploratory and hypothesis-generating nature of these analyses, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. All regression analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) and Euler diagrams were created in the R environment for statistical computing, version 4.0.0.

RESULTS

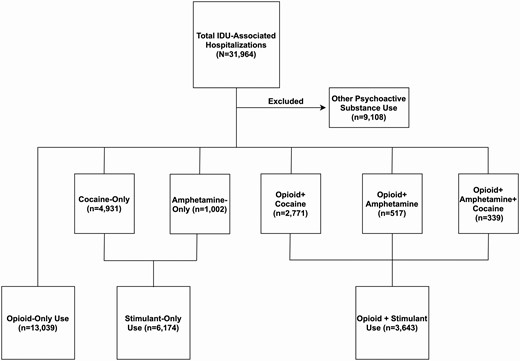

During the study period, there were 31 964 hospitalizations of PWID for IDU-associated infectious diseases in Florida (Figure 1). The study cohort of 22 856 hospitalizations included diagnostic codes for opioids or stimulants. Opioid use was present in 73% of cases (opioid-only + opioid/stimulant) while stimulant use was present in 43% (stimulant-only + opioid/stimulant) (Table 1). Stimulants-only were present in 27% of PWID hospitalizations for IDU-associated infections. The median age of the cohort was 44 years (IQR 33–56), half female (46%), and mostly non-Hispanic white (80%). SSTI and sepsis/bacteremia were each present in about half of hospitalizations. The in-hospital mortality was 4%, and 15% had patient-directed discharge. Compared to opioid-only and opioid/stimulant, the group of people who used stimulants-only had more males (62%), more non-Hispanic black race (25%), the highest HIV rate (11%), and the most alcohol use diagnoses (20%). Supplementary Table 2 provides these data for people who use stimulants broken down by cocaine versus amphetamine use. The opioid/stimulant group was youngest, most uninsured (51%), with lower burden of comorbidities. In addition, the opioid/stimulant group had the most endocarditis diagnoses (16%), highest burden of HCV infection (44%) and the most patient-directed discharge (25%).

Flow diagram of IDU-associated infections in Florida. Abbreviation: IDU, injection drug use.

Characteristics of People Who Inject Drugs Hospitalized for Injection Drug Use-associated Infections in Florida, 2016–2017, Stratified by Substance Used

| Characteristic . | Overall, n (%) N = 22 856 . | Opioids-only, n (%) n = 13 039 . | Stimulant-only, N (%) n = 6174 . | Opioid/Stimulant, N (%) n = 3643 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 6665 (31.1) | 3310 (27.1) | 1645 (28.4) | 1710 (49.5) |

| 35–54 | 9347 (43.6) | 4882 (40.0) | 2971 (51.3) | 1494 (43.2) |

| 55–64 | 3896 (18.2) | 2648 (21.7) | 1018 (17.6) | 230 (6.7) |

| 65–75 | 1554 (7.3) | 1375 (11.3) | 155 (2.7) | 24 (0.7) |

| Age (median, IQR) | 44 (33–56) | 47 (34–58) | 44 (34–54) | 35 (29–44) |

| Male | 12 266 (53.7) | 6675 (51.2) | 3812 (61.7) | 1779 (49.1) |

| Female | 10 574 (46.3) | 6364 (48.8) | 2362 (38.3) | 1848 (50.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 17 654 (79.6) | 10 832 (85.4) | 3869 (64.6) | 2953 (84.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2619 (11.8) | 892 (7.0) | 1511 (25.2) | 216 (6.2) |

| Hispanic | 1914 (8.6) | 958 (7.6) | 614 (10.2) | 342 (9.7) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 6968 (30.5) | 5187 (39.8) | 1324 (21.4) | 457 (12.6) |

| Medicaid | 5964 (26.1) | 3030 (23.2) | 1998 (32.4) | 936 (25.8) |

| Private | 2610 (11.4) | 1682 (12.9) | 545 (8.8) | 383 (10.6) |

| Uninsured | 7298 (32.0) | 3140 (24.1) | 2307 (37.4) | 1851 (51.0) |

| Infection | ||||

| Endocarditis | 2207 (9.7) | 1238 (9.5) | 388 (6.3) | 581 (16.0) |

| SSTI | 11 302 (49.5) | 6081 (46.6) | 3199 (51.8) | 2022 (55.8) |

| Osteomyelitis | 3240 (14.2) | 2084 (16.0) | 709 (11.5) | 447 (12.3) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 11 915 (52.2) | 7062 (54.2) | 3069 (49.7) | 1784 (49.2) |

| Comorbidity Present | ||||

| HIV-positive | 1085 (4.8) | 295 (2.3) | 649 (10.5) | 141 (3.9) |

| HCV-positive | 5925 (25.9) | 2962 (22.7) | 1350 (21.9) | 1613 (44.3) |

| Heart Failure | 2268 (9.9) | 1443 (11.1) | 655 (10.6) | 170 (4.7) |

| Hypertension | 8844 (38.7) | 5638 (43.2) | 2424 (39.3) | 782 (21.5) |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 4277 (18.7) | 2926 (22.4) | 1045 (16.9) | 306 (8.4) |

| Diabetes | 4620 (20.2) | 3103 (23.8) | 1217 (19.7) | 300 (8.2) |

| Renal Disease | 2577 (11.3) | 1733 (13.3) | 688 (11.1) | 156 (4.3) |

| Alcohol | 2726 (11.9) | 1092 (8.4) | 1204 (19.5) | 430 (11.8) |

| Psychoses | 994 (4.4) | 290 (2.2) | 537 (8.7) | 167 (4.6) |

| Depression | 4879 (21.4) | 3066 (23.5) | 1088 (17.6) | 725 (19.9) |

| Overdose | 1563 (6.8) | 963 (7.4) | 293 (4.8) | 307 (8.5) |

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 6.0 (3–12) | 6.0 (3–13) | 5.0 (3–10) | 5.0 (2–11) |

| Disposition | ||||

| Discharged | 18 572 (81.3) | 10 962 (84.1) | 4978 (80.6) | 2632 (72.3) |

| In-hospital mortality | 823 (3.6) | 458 (3.5) | 264 (4.3) | 101 (2.8) |

| Patient-directed discharge | 3461 (15.1) | 1619 (12.4) | 932 (15.1) | 910 (25.0) |

| Characteristic . | Overall, n (%) N = 22 856 . | Opioids-only, n (%) n = 13 039 . | Stimulant-only, N (%) n = 6174 . | Opioid/Stimulant, N (%) n = 3643 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 6665 (31.1) | 3310 (27.1) | 1645 (28.4) | 1710 (49.5) |

| 35–54 | 9347 (43.6) | 4882 (40.0) | 2971 (51.3) | 1494 (43.2) |

| 55–64 | 3896 (18.2) | 2648 (21.7) | 1018 (17.6) | 230 (6.7) |

| 65–75 | 1554 (7.3) | 1375 (11.3) | 155 (2.7) | 24 (0.7) |

| Age (median, IQR) | 44 (33–56) | 47 (34–58) | 44 (34–54) | 35 (29–44) |

| Male | 12 266 (53.7) | 6675 (51.2) | 3812 (61.7) | 1779 (49.1) |

| Female | 10 574 (46.3) | 6364 (48.8) | 2362 (38.3) | 1848 (50.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 17 654 (79.6) | 10 832 (85.4) | 3869 (64.6) | 2953 (84.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2619 (11.8) | 892 (7.0) | 1511 (25.2) | 216 (6.2) |

| Hispanic | 1914 (8.6) | 958 (7.6) | 614 (10.2) | 342 (9.7) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 6968 (30.5) | 5187 (39.8) | 1324 (21.4) | 457 (12.6) |

| Medicaid | 5964 (26.1) | 3030 (23.2) | 1998 (32.4) | 936 (25.8) |

| Private | 2610 (11.4) | 1682 (12.9) | 545 (8.8) | 383 (10.6) |

| Uninsured | 7298 (32.0) | 3140 (24.1) | 2307 (37.4) | 1851 (51.0) |

| Infection | ||||

| Endocarditis | 2207 (9.7) | 1238 (9.5) | 388 (6.3) | 581 (16.0) |

| SSTI | 11 302 (49.5) | 6081 (46.6) | 3199 (51.8) | 2022 (55.8) |

| Osteomyelitis | 3240 (14.2) | 2084 (16.0) | 709 (11.5) | 447 (12.3) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 11 915 (52.2) | 7062 (54.2) | 3069 (49.7) | 1784 (49.2) |

| Comorbidity Present | ||||

| HIV-positive | 1085 (4.8) | 295 (2.3) | 649 (10.5) | 141 (3.9) |

| HCV-positive | 5925 (25.9) | 2962 (22.7) | 1350 (21.9) | 1613 (44.3) |

| Heart Failure | 2268 (9.9) | 1443 (11.1) | 655 (10.6) | 170 (4.7) |

| Hypertension | 8844 (38.7) | 5638 (43.2) | 2424 (39.3) | 782 (21.5) |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 4277 (18.7) | 2926 (22.4) | 1045 (16.9) | 306 (8.4) |

| Diabetes | 4620 (20.2) | 3103 (23.8) | 1217 (19.7) | 300 (8.2) |

| Renal Disease | 2577 (11.3) | 1733 (13.3) | 688 (11.1) | 156 (4.3) |

| Alcohol | 2726 (11.9) | 1092 (8.4) | 1204 (19.5) | 430 (11.8) |

| Psychoses | 994 (4.4) | 290 (2.2) | 537 (8.7) | 167 (4.6) |

| Depression | 4879 (21.4) | 3066 (23.5) | 1088 (17.6) | 725 (19.9) |

| Overdose | 1563 (6.8) | 963 (7.4) | 293 (4.8) | 307 (8.5) |

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 6.0 (3–12) | 6.0 (3–13) | 5.0 (3–10) | 5.0 (2–11) |

| Disposition | ||||

| Discharged | 18 572 (81.3) | 10 962 (84.1) | 4978 (80.6) | 2632 (72.3) |

| In-hospital mortality | 823 (3.6) | 458 (3.5) | 264 (4.3) | 101 (2.8) |

| Patient-directed discharge | 3461 (15.1) | 1619 (12.4) | 932 (15.1) | 910 (25.0) |

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

Characteristics of People Who Inject Drugs Hospitalized for Injection Drug Use-associated Infections in Florida, 2016–2017, Stratified by Substance Used

| Characteristic . | Overall, n (%) N = 22 856 . | Opioids-only, n (%) n = 13 039 . | Stimulant-only, N (%) n = 6174 . | Opioid/Stimulant, N (%) n = 3643 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 6665 (31.1) | 3310 (27.1) | 1645 (28.4) | 1710 (49.5) |

| 35–54 | 9347 (43.6) | 4882 (40.0) | 2971 (51.3) | 1494 (43.2) |

| 55–64 | 3896 (18.2) | 2648 (21.7) | 1018 (17.6) | 230 (6.7) |

| 65–75 | 1554 (7.3) | 1375 (11.3) | 155 (2.7) | 24 (0.7) |

| Age (median, IQR) | 44 (33–56) | 47 (34–58) | 44 (34–54) | 35 (29–44) |

| Male | 12 266 (53.7) | 6675 (51.2) | 3812 (61.7) | 1779 (49.1) |

| Female | 10 574 (46.3) | 6364 (48.8) | 2362 (38.3) | 1848 (50.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 17 654 (79.6) | 10 832 (85.4) | 3869 (64.6) | 2953 (84.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2619 (11.8) | 892 (7.0) | 1511 (25.2) | 216 (6.2) |

| Hispanic | 1914 (8.6) | 958 (7.6) | 614 (10.2) | 342 (9.7) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 6968 (30.5) | 5187 (39.8) | 1324 (21.4) | 457 (12.6) |

| Medicaid | 5964 (26.1) | 3030 (23.2) | 1998 (32.4) | 936 (25.8) |

| Private | 2610 (11.4) | 1682 (12.9) | 545 (8.8) | 383 (10.6) |

| Uninsured | 7298 (32.0) | 3140 (24.1) | 2307 (37.4) | 1851 (51.0) |

| Infection | ||||

| Endocarditis | 2207 (9.7) | 1238 (9.5) | 388 (6.3) | 581 (16.0) |

| SSTI | 11 302 (49.5) | 6081 (46.6) | 3199 (51.8) | 2022 (55.8) |

| Osteomyelitis | 3240 (14.2) | 2084 (16.0) | 709 (11.5) | 447 (12.3) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 11 915 (52.2) | 7062 (54.2) | 3069 (49.7) | 1784 (49.2) |

| Comorbidity Present | ||||

| HIV-positive | 1085 (4.8) | 295 (2.3) | 649 (10.5) | 141 (3.9) |

| HCV-positive | 5925 (25.9) | 2962 (22.7) | 1350 (21.9) | 1613 (44.3) |

| Heart Failure | 2268 (9.9) | 1443 (11.1) | 655 (10.6) | 170 (4.7) |

| Hypertension | 8844 (38.7) | 5638 (43.2) | 2424 (39.3) | 782 (21.5) |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 4277 (18.7) | 2926 (22.4) | 1045 (16.9) | 306 (8.4) |

| Diabetes | 4620 (20.2) | 3103 (23.8) | 1217 (19.7) | 300 (8.2) |

| Renal Disease | 2577 (11.3) | 1733 (13.3) | 688 (11.1) | 156 (4.3) |

| Alcohol | 2726 (11.9) | 1092 (8.4) | 1204 (19.5) | 430 (11.8) |

| Psychoses | 994 (4.4) | 290 (2.2) | 537 (8.7) | 167 (4.6) |

| Depression | 4879 (21.4) | 3066 (23.5) | 1088 (17.6) | 725 (19.9) |

| Overdose | 1563 (6.8) | 963 (7.4) | 293 (4.8) | 307 (8.5) |

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 6.0 (3–12) | 6.0 (3–13) | 5.0 (3–10) | 5.0 (2–11) |

| Disposition | ||||

| Discharged | 18 572 (81.3) | 10 962 (84.1) | 4978 (80.6) | 2632 (72.3) |

| In-hospital mortality | 823 (3.6) | 458 (3.5) | 264 (4.3) | 101 (2.8) |

| Patient-directed discharge | 3461 (15.1) | 1619 (12.4) | 932 (15.1) | 910 (25.0) |

| Characteristic . | Overall, n (%) N = 22 856 . | Opioids-only, n (%) n = 13 039 . | Stimulant-only, N (%) n = 6174 . | Opioid/Stimulant, N (%) n = 3643 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 6665 (31.1) | 3310 (27.1) | 1645 (28.4) | 1710 (49.5) |

| 35–54 | 9347 (43.6) | 4882 (40.0) | 2971 (51.3) | 1494 (43.2) |

| 55–64 | 3896 (18.2) | 2648 (21.7) | 1018 (17.6) | 230 (6.7) |

| 65–75 | 1554 (7.3) | 1375 (11.3) | 155 (2.7) | 24 (0.7) |

| Age (median, IQR) | 44 (33–56) | 47 (34–58) | 44 (34–54) | 35 (29–44) |

| Male | 12 266 (53.7) | 6675 (51.2) | 3812 (61.7) | 1779 (49.1) |

| Female | 10 574 (46.3) | 6364 (48.8) | 2362 (38.3) | 1848 (50.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 17 654 (79.6) | 10 832 (85.4) | 3869 (64.6) | 2953 (84.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2619 (11.8) | 892 (7.0) | 1511 (25.2) | 216 (6.2) |

| Hispanic | 1914 (8.6) | 958 (7.6) | 614 (10.2) | 342 (9.7) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 6968 (30.5) | 5187 (39.8) | 1324 (21.4) | 457 (12.6) |

| Medicaid | 5964 (26.1) | 3030 (23.2) | 1998 (32.4) | 936 (25.8) |

| Private | 2610 (11.4) | 1682 (12.9) | 545 (8.8) | 383 (10.6) |

| Uninsured | 7298 (32.0) | 3140 (24.1) | 2307 (37.4) | 1851 (51.0) |

| Infection | ||||

| Endocarditis | 2207 (9.7) | 1238 (9.5) | 388 (6.3) | 581 (16.0) |

| SSTI | 11 302 (49.5) | 6081 (46.6) | 3199 (51.8) | 2022 (55.8) |

| Osteomyelitis | 3240 (14.2) | 2084 (16.0) | 709 (11.5) | 447 (12.3) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 11 915 (52.2) | 7062 (54.2) | 3069 (49.7) | 1784 (49.2) |

| Comorbidity Present | ||||

| HIV-positive | 1085 (4.8) | 295 (2.3) | 649 (10.5) | 141 (3.9) |

| HCV-positive | 5925 (25.9) | 2962 (22.7) | 1350 (21.9) | 1613 (44.3) |

| Heart Failure | 2268 (9.9) | 1443 (11.1) | 655 (10.6) | 170 (4.7) |

| Hypertension | 8844 (38.7) | 5638 (43.2) | 2424 (39.3) | 782 (21.5) |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 4277 (18.7) | 2926 (22.4) | 1045 (16.9) | 306 (8.4) |

| Diabetes | 4620 (20.2) | 3103 (23.8) | 1217 (19.7) | 300 (8.2) |

| Renal Disease | 2577 (11.3) | 1733 (13.3) | 688 (11.1) | 156 (4.3) |

| Alcohol | 2726 (11.9) | 1092 (8.4) | 1204 (19.5) | 430 (11.8) |

| Psychoses | 994 (4.4) | 290 (2.2) | 537 (8.7) | 167 (4.6) |

| Depression | 4879 (21.4) | 3066 (23.5) | 1088 (17.6) | 725 (19.9) |

| Overdose | 1563 (6.8) | 963 (7.4) | 293 (4.8) | 307 (8.5) |

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 6.0 (3–12) | 6.0 (3–13) | 5.0 (3–10) | 5.0 (2–11) |

| Disposition | ||||

| Discharged | 18 572 (81.3) | 10 962 (84.1) | 4978 (80.6) | 2632 (72.3) |

| In-hospital mortality | 823 (3.6) | 458 (3.5) | 264 (4.3) | 101 (2.8) |

| Patient-directed discharge | 3461 (15.1) | 1619 (12.4) | 932 (15.1) | 910 (25.0) |

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

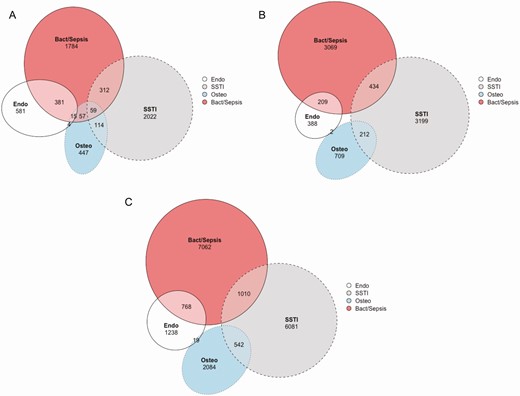

Table 2 shows the association between patient characteristics and the adjusted risk of particular infections. Compared to opioid-only users, those with opioid/stimulant use were more likely to have endocarditis (aRR = 1.12, 95% CI 1.01–1.24) and stimulant-only users were less likely (aRR = 0.68, 95% CI .60–.77). People who used opioids-only had the highest risk of osteomyelitis. The Euler diagrams in Figure 2 demonstrate overlapping infection diagnoses among PWID in each substance use group. SSTI with bacteremia/sepsis was the most common combination of infections among people who used opioids-only and stimulants-only, whereas endocarditis with bacteremia/sepsis was the most common combination among those using opioids/stimulants.

Factors Associated With Endocarditis, SSTIs, Osteomyelitis, and Bacteremia/Sepsis Among People Who Inject Drugs Hospitalized in Florida (n = 22 856)

| . | Endocarditis . | SSTI . | Osteomyelitis . | Bacteremia/Sepsis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Drug Use | ||||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.15) | 0.86 (.77, .96) | 0.97 (.92, 1.02) |

| Stimulant-only | 0.68 (.60, .77) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.16) | 0.70 (.64, .77) | 0.92 (.87, .96) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 4.29 (3.00, 6.12) | 1.24 (1.13, 1.37) | 0.95 (.80, 1.14) | 0.89 (.82, .96) |

| 35–54 | 3.24 (2.29, 4.60) | 1.23 (1.13, 1.35) | 1.60 (1.37, 1.87) | 0.84 (.78, .91) |

| 55–64 | 1.49 (1.03, 2.15) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | 1.37 (1.17, 1.60) | 0.90 (.83, .97) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.77 (.70, .84) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) | 1.50 (1.39, 1.61) | 0.85 (.82, .88) |

| Female | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Race | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.87 (.72, 1.03) | 0.94 (.87,1.01) | 0.78 (.68, .90) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.68 (.56, .83) | 0.71 (.66, .76) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.26) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 0.71 (.58, .85) | 1.03 (.96, 1.10) | 1.11 (.97, 1.27) | 0.98 (.91, 1.05) |

| Medicaid | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) | 1.03 (.96, 1.11) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.47) | 0.96 (.90, 1.03) |

| Uninsured | 1.12 (.96, 1.30) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | 0.96 (.84, 1.10) | 0.88 (.82, .94) |

| Private | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| HIV-positive | 0.73 (.56, .94) | 0.91 (.82, 1.00) | 0.57 (.46, .71) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.26) |

| HCV-positive | 2.14 (1.96, 2.34) | 0.98 (.94, 1.03) | 1.26 (1.16, 1.37) | 1.02 (.98, 1.07) |

| Diabetes | 0.53 (.45, .63) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.17) | 1.77 (1.63, 1.92) | 0.87 (.83, .91) |

| Heart Failure | 2.70 (2.37, 3.07) | 0.68 (.63, .74) | 0.55 (.48, .64) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) |

| Alcohol | 0.74 (.63, .87) | 0.98 (.92, 1.04) | 0.83 (.75, .94) | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) |

| . | Endocarditis . | SSTI . | Osteomyelitis . | Bacteremia/Sepsis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Drug Use | ||||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.15) | 0.86 (.77, .96) | 0.97 (.92, 1.02) |

| Stimulant-only | 0.68 (.60, .77) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.16) | 0.70 (.64, .77) | 0.92 (.87, .96) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 4.29 (3.00, 6.12) | 1.24 (1.13, 1.37) | 0.95 (.80, 1.14) | 0.89 (.82, .96) |

| 35–54 | 3.24 (2.29, 4.60) | 1.23 (1.13, 1.35) | 1.60 (1.37, 1.87) | 0.84 (.78, .91) |

| 55–64 | 1.49 (1.03, 2.15) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | 1.37 (1.17, 1.60) | 0.90 (.83, .97) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.77 (.70, .84) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) | 1.50 (1.39, 1.61) | 0.85 (.82, .88) |

| Female | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Race | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.87 (.72, 1.03) | 0.94 (.87,1.01) | 0.78 (.68, .90) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.68 (.56, .83) | 0.71 (.66, .76) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.26) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 0.71 (.58, .85) | 1.03 (.96, 1.10) | 1.11 (.97, 1.27) | 0.98 (.91, 1.05) |

| Medicaid | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) | 1.03 (.96, 1.11) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.47) | 0.96 (.90, 1.03) |

| Uninsured | 1.12 (.96, 1.30) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | 0.96 (.84, 1.10) | 0.88 (.82, .94) |

| Private | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| HIV-positive | 0.73 (.56, .94) | 0.91 (.82, 1.00) | 0.57 (.46, .71) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.26) |

| HCV-positive | 2.14 (1.96, 2.34) | 0.98 (.94, 1.03) | 1.26 (1.16, 1.37) | 1.02 (.98, 1.07) |

| Diabetes | 0.53 (.45, .63) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.17) | 1.77 (1.63, 1.92) | 0.87 (.83, .91) |

| Heart Failure | 2.70 (2.37, 3.07) | 0.68 (.63, .74) | 0.55 (.48, .64) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) |

| Alcohol | 0.74 (.63, .87) | 0.98 (.92, 1.04) | 0.83 (.75, .94) | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) |

Note: Bolded values represented P values < .05.

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

aAnalyses adjusted for all variables presented.

Factors Associated With Endocarditis, SSTIs, Osteomyelitis, and Bacteremia/Sepsis Among People Who Inject Drugs Hospitalized in Florida (n = 22 856)

| . | Endocarditis . | SSTI . | Osteomyelitis . | Bacteremia/Sepsis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Drug Use | ||||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.15) | 0.86 (.77, .96) | 0.97 (.92, 1.02) |

| Stimulant-only | 0.68 (.60, .77) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.16) | 0.70 (.64, .77) | 0.92 (.87, .96) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 4.29 (3.00, 6.12) | 1.24 (1.13, 1.37) | 0.95 (.80, 1.14) | 0.89 (.82, .96) |

| 35–54 | 3.24 (2.29, 4.60) | 1.23 (1.13, 1.35) | 1.60 (1.37, 1.87) | 0.84 (.78, .91) |

| 55–64 | 1.49 (1.03, 2.15) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | 1.37 (1.17, 1.60) | 0.90 (.83, .97) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.77 (.70, .84) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) | 1.50 (1.39, 1.61) | 0.85 (.82, .88) |

| Female | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Race | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.87 (.72, 1.03) | 0.94 (.87,1.01) | 0.78 (.68, .90) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.68 (.56, .83) | 0.71 (.66, .76) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.26) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 0.71 (.58, .85) | 1.03 (.96, 1.10) | 1.11 (.97, 1.27) | 0.98 (.91, 1.05) |

| Medicaid | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) | 1.03 (.96, 1.11) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.47) | 0.96 (.90, 1.03) |

| Uninsured | 1.12 (.96, 1.30) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | 0.96 (.84, 1.10) | 0.88 (.82, .94) |

| Private | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| HIV-positive | 0.73 (.56, .94) | 0.91 (.82, 1.00) | 0.57 (.46, .71) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.26) |

| HCV-positive | 2.14 (1.96, 2.34) | 0.98 (.94, 1.03) | 1.26 (1.16, 1.37) | 1.02 (.98, 1.07) |

| Diabetes | 0.53 (.45, .63) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.17) | 1.77 (1.63, 1.92) | 0.87 (.83, .91) |

| Heart Failure | 2.70 (2.37, 3.07) | 0.68 (.63, .74) | 0.55 (.48, .64) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) |

| Alcohol | 0.74 (.63, .87) | 0.98 (.92, 1.04) | 0.83 (.75, .94) | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) |

| . | Endocarditis . | SSTI . | Osteomyelitis . | Bacteremia/Sepsis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Drug Use | ||||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.15) | 0.86 (.77, .96) | 0.97 (.92, 1.02) |

| Stimulant-only | 0.68 (.60, .77) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.16) | 0.70 (.64, .77) | 0.92 (.87, .96) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 4.29 (3.00, 6.12) | 1.24 (1.13, 1.37) | 0.95 (.80, 1.14) | 0.89 (.82, .96) |

| 35–54 | 3.24 (2.29, 4.60) | 1.23 (1.13, 1.35) | 1.60 (1.37, 1.87) | 0.84 (.78, .91) |

| 55–64 | 1.49 (1.03, 2.15) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | 1.37 (1.17, 1.60) | 0.90 (.83, .97) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.77 (.70, .84) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) | 1.50 (1.39, 1.61) | 0.85 (.82, .88) |

| Female | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Race | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.87 (.72, 1.03) | 0.94 (.87,1.01) | 0.78 (.68, .90) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.68 (.56, .83) | 0.71 (.66, .76) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.26) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 0.71 (.58, .85) | 1.03 (.96, 1.10) | 1.11 (.97, 1.27) | 0.98 (.91, 1.05) |

| Medicaid | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) | 1.03 (.96, 1.11) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.47) | 0.96 (.90, 1.03) |

| Uninsured | 1.12 (.96, 1.30) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | 0.96 (.84, 1.10) | 0.88 (.82, .94) |

| Private | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| HIV-positive | 0.73 (.56, .94) | 0.91 (.82, 1.00) | 0.57 (.46, .71) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.26) |

| HCV-positive | 2.14 (1.96, 2.34) | 0.98 (.94, 1.03) | 1.26 (1.16, 1.37) | 1.02 (.98, 1.07) |

| Diabetes | 0.53 (.45, .63) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.17) | 1.77 (1.63, 1.92) | 0.87 (.83, .91) |

| Heart Failure | 2.70 (2.37, 3.07) | 0.68 (.63, .74) | 0.55 (.48, .64) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) |

| Alcohol | 0.74 (.63, .87) | 0.98 (.92, 1.04) | 0.83 (.75, .94) | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) |

Note: Bolded values represented P values < .05.

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

aAnalyses adjusted for all variables presented.

Euler diagrams of infection distribution among people who inject drugs hospitalized in Florida, stratified by substance used. A, Opioid/Stimulant, B, Stimulant-only, and C, Opioid-only use. Ellipses represent the proportional frequency of each infection diagnosis with areas of overlap representing people with multiple infection diagnoses. Cases with all 4 diagnoses present are not graphically represented, their frequency is: opioid-only 25, stimulant-only 6, opioid/stimulant 17. Abbreviations: Bact/sepsis, bacteremia/sepsis; endo, endocarditis; osteo, osteomyelitis; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

In adjusted regression models, opioid/stimulant use was associated with patient-directed discharge compared to opioid-only use (aRR 1.28, 95% CI 1.17–1.4) (Table 3). Younger age, female sex, and uninsured status were also associated with patient-directed discharge. Among the different infections, having endocarditis was a risk factor for patient-directed discharge. Compared to opioid-only use, those who used stimulants-only were 26% more likely to experience in-hospital mortality. Sepsis/bacteremia and endocarditis were associated with increased risk of death, whereas presence of SSTI or osteomyelitis was associated with decreased in-hospital mortality.

Factors Associated With Patient-directed Discharge and In-hospital Mortality Among People Who Inject Drugs Hospitalized With Injection Drug Use-associated Infections in Florida

| . | Patient-directed Discharge . | In-hospital Mortality . |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Substance Use | ||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.28 (1.17, 1.40) | 0.99 (.78, 1.25) |

| Stimulant-only | 1.09 (1.00, 1.19) | 1.26 (1.03, 1.46) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF |

| Age | ||

| 18–34 | 4.87 (3.41, 6.96) | 0.41 (.30, .56) |

| 35–54 | 3.97 (2.79, 5.63) | 0.62 (.48, .81) |

| 55–64 | 2.20 (1.53, 3.15) | 0.90 (.70, 1.15) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||

| Male | 0.86 (.80, .92) | 1.09 (.95, 1.27) |

| Female | REF | REF |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 0.97 (.85, 1.10) | 1.27 (1.01, 1.61) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.75 (.65, .86) | 0.85 (.68, 1.07) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 1.09 (.93, 1.29) | 0.96 (.74, 1.25) |

| Medicaid | 1.49 (1.29, 1.72) | 1.41 (1.09, 1.82) |

| Uninsured | 2.07 (1.81, 2.38) | 0.74 (.55, .98) |

| Private | REF | REF |

| Infection | ||

| Endocarditis | 1.36 (1.23, 1.51) | 1.80 (1.46, 2.21) |

| SSTI | 0.97 (.89, 1.06) | 0.46 (.35, .59) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1.05 (.94, 1.17) | 0.48 (.32, .71) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 1.07 (.98, 1.17) | 9.44 (6.43, 13.85) |

| HIV-positive | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40) | 1.24 (.94, 1.64) |

| HCV-positive | 1.07 (.99, 1.15) | 0.90 (.75, 1.08) |

| Depression | 0.71 (.64, .78) | 0.71 (.58, .86) |

| Psychoses | 1.02 (.85, 1.23) | 0.65 (.42, 1.00) |

| Overdose | 0.87 (.74, 1.01) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.59) |

| . | Patient-directed Discharge . | In-hospital Mortality . |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Substance Use | ||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.28 (1.17, 1.40) | 0.99 (.78, 1.25) |

| Stimulant-only | 1.09 (1.00, 1.19) | 1.26 (1.03, 1.46) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF |

| Age | ||

| 18–34 | 4.87 (3.41, 6.96) | 0.41 (.30, .56) |

| 35–54 | 3.97 (2.79, 5.63) | 0.62 (.48, .81) |

| 55–64 | 2.20 (1.53, 3.15) | 0.90 (.70, 1.15) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||

| Male | 0.86 (.80, .92) | 1.09 (.95, 1.27) |

| Female | REF | REF |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 0.97 (.85, 1.10) | 1.27 (1.01, 1.61) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.75 (.65, .86) | 0.85 (.68, 1.07) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 1.09 (.93, 1.29) | 0.96 (.74, 1.25) |

| Medicaid | 1.49 (1.29, 1.72) | 1.41 (1.09, 1.82) |

| Uninsured | 2.07 (1.81, 2.38) | 0.74 (.55, .98) |

| Private | REF | REF |

| Infection | ||

| Endocarditis | 1.36 (1.23, 1.51) | 1.80 (1.46, 2.21) |

| SSTI | 0.97 (.89, 1.06) | 0.46 (.35, .59) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1.05 (.94, 1.17) | 0.48 (.32, .71) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 1.07 (.98, 1.17) | 9.44 (6.43, 13.85) |

| HIV-positive | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40) | 1.24 (.94, 1.64) |

| HCV-positive | 1.07 (.99, 1.15) | 0.90 (.75, 1.08) |

| Depression | 0.71 (.64, .78) | 0.71 (.58, .86) |

| Psychoses | 1.02 (.85, 1.23) | 0.65 (.42, 1.00) |

| Overdose | 0.87 (.74, 1.01) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.59) |

Note: Bolded values represented P values < .05.

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

aAnalyses adjusted for all variables presented as well as all other comorbidities in Table 1.

Factors Associated With Patient-directed Discharge and In-hospital Mortality Among People Who Inject Drugs Hospitalized With Injection Drug Use-associated Infections in Florida

| . | Patient-directed Discharge . | In-hospital Mortality . |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Substance Use | ||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.28 (1.17, 1.40) | 0.99 (.78, 1.25) |

| Stimulant-only | 1.09 (1.00, 1.19) | 1.26 (1.03, 1.46) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF |

| Age | ||

| 18–34 | 4.87 (3.41, 6.96) | 0.41 (.30, .56) |

| 35–54 | 3.97 (2.79, 5.63) | 0.62 (.48, .81) |

| 55–64 | 2.20 (1.53, 3.15) | 0.90 (.70, 1.15) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||

| Male | 0.86 (.80, .92) | 1.09 (.95, 1.27) |

| Female | REF | REF |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 0.97 (.85, 1.10) | 1.27 (1.01, 1.61) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.75 (.65, .86) | 0.85 (.68, 1.07) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 1.09 (.93, 1.29) | 0.96 (.74, 1.25) |

| Medicaid | 1.49 (1.29, 1.72) | 1.41 (1.09, 1.82) |

| Uninsured | 2.07 (1.81, 2.38) | 0.74 (.55, .98) |

| Private | REF | REF |

| Infection | ||

| Endocarditis | 1.36 (1.23, 1.51) | 1.80 (1.46, 2.21) |

| SSTI | 0.97 (.89, 1.06) | 0.46 (.35, .59) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1.05 (.94, 1.17) | 0.48 (.32, .71) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 1.07 (.98, 1.17) | 9.44 (6.43, 13.85) |

| HIV-positive | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40) | 1.24 (.94, 1.64) |

| HCV-positive | 1.07 (.99, 1.15) | 0.90 (.75, 1.08) |

| Depression | 0.71 (.64, .78) | 0.71 (.58, .86) |

| Psychoses | 1.02 (.85, 1.23) | 0.65 (.42, 1.00) |

| Overdose | 0.87 (.74, 1.01) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.59) |

| . | Patient-directed Discharge . | In-hospital Mortality . |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | aRR (95% CI)a . | aRR (95% CI) . |

| Substance Use | ||

| Opioid/Stimulant | 1.28 (1.17, 1.40) | 0.99 (.78, 1.25) |

| Stimulant-only | 1.09 (1.00, 1.19) | 1.26 (1.03, 1.46) |

| Opioid-only | REF | REF |

| Age | ||

| 18–34 | 4.87 (3.41, 6.96) | 0.41 (.30, .56) |

| 35–54 | 3.97 (2.79, 5.63) | 0.62 (.48, .81) |

| 55–64 | 2.20 (1.53, 3.15) | 0.90 (.70, 1.15) |

| 65–75 | REF | REF |

| Biological Sex | ||

| Male | 0.86 (.80, .92) | 1.09 (.95, 1.27) |

| Female | REF | REF |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 0.97 (.85, 1.10) | 1.27 (1.01, 1.61) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.75 (.65, .86) | 0.85 (.68, 1.07) |

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 1.09 (.93, 1.29) | 0.96 (.74, 1.25) |

| Medicaid | 1.49 (1.29, 1.72) | 1.41 (1.09, 1.82) |

| Uninsured | 2.07 (1.81, 2.38) | 0.74 (.55, .98) |

| Private | REF | REF |

| Infection | ||

| Endocarditis | 1.36 (1.23, 1.51) | 1.80 (1.46, 2.21) |

| SSTI | 0.97 (.89, 1.06) | 0.46 (.35, .59) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1.05 (.94, 1.17) | 0.48 (.32, .71) |

| Sepsis/Bacteremia | 1.07 (.98, 1.17) | 9.44 (6.43, 13.85) |

| HIV-positive | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40) | 1.24 (.94, 1.64) |

| HCV-positive | 1.07 (.99, 1.15) | 0.90 (.75, 1.08) |

| Depression | 0.71 (.64, .78) | 0.71 (.58, .86) |

| Psychoses | 1.02 (.85, 1.23) | 0.65 (.42, 1.00) |

| Overdose | 0.87 (.74, 1.01) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.59) |

Note: Bolded values represented P values < .05.

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

aAnalyses adjusted for all variables presented as well as all other comorbidities in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Between 2016 and 2017, there were over 20 000 hospitalizations for IDU-associated infectious diseases in Florida among people who use opioids or stimulants. While opioid use was involved in the majority of these infections, we found that stimulant use contributed to 43% of infections and was the sole substance used in over a quarter of infections. Categorizing IDU-associated infections by the contributing substance used revealed distinct demographics, comorbidities, infections, and hospitalization outcomes between opioid-only, stimulant-only, and opioid/stimulant-associated infections. Hospitalized PWID using opioids/stimulants were more likely to present with endocarditis and more likely to have patient-directed discharge, while stimulant-only use hospitalizations had the highest in-hospital mortality. These findings demonstrate substance-specific heterogeneity in hospitalizations for IDU-associated infections, which has important implications for both public health and clinical approaches to infection prevention and treatment.

The use of both opioids/stimulants was an important risk factor for negative outcomes, including endocarditis and patient-directed discharge. Additionally, people with opioid/stimulant use were youngest, more likely to have HCV infection, and had the highest rate of uninsured status. These results are concordant with our previous work showing that among clients at our syringe services program (SSP) in Miami, Florida, those who used opioids/cocaine were more likely to share syringes and to have HCV infection [17]. Syringe sharing is a risk factor for invasive bacterial infections [26] and presence of HCV is a direct surrogate of future HIV infection [27], highlighting the need for access to low barrier harm reduction services for this population. People with polysubstance use had markers of lower socioeconomic status: most uninsured status in this study and most likely to experience homelessness in our SSP cohort. Addressing these social determinants of health by expanded access to health insurance and affordable housing is critical to preventing drug and infection-related morbidity and mortality.

The high rate of stimulant use among patients hospitalized with IDU-associated infections poses unique challenges in treatment versus opioid-only drug use-associated infections. Successful treatment of IDU-associated infections hinges upon treatment of the underlying SUD. Evidence suggests that use of MOUD for OUD-associated infections is associated with improved infection and addiction-related outcomes [12, 28]; however, the best treatment for infections involving stimulant use—for which no highly effective medication exists—is unknown. Effective evidence-based behavioral interventions for stimulant use disorders include cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management, but little is known about how these approaches might work in the acute care setting [29]. MOUD has been shown to decrease concomitant stimulant use among people with opioid/stimulant use disorders [30], but stimulant use is also a risk factor for ongoing opioid use and disengagement from addiction treatment [31, 32]. While acute opioid withdrawal can be effectively treated with methadone or buprenorphine, managing stimulant withdrawal and cravings is more difficult in the inpatient setting and can interfere with receipt of medical care. This could have contributed the higher rates of patient-directed discharge seen in this study and described by others [33].

Injection of stimulants is hypothesized mechanistically to predispose to endocarditis more than opioids based on increased thrombogenicity and valve tissue ischemia from vasoconstriction [34]. Cocaine injection, as well as cocaine/heroin injection, have both been associated with increased risk for SSTI and endocarditis [35–37]. We found that stimulant-only use was associated with the lowest risk of endocarditis and polysubstance use with the highest risk. We suspect these differences are more related to socio-demographics and injection practices, such as reusing syringes and increased frequency of injection, rather than a pathophysiologic predisposition to infection. Crushed opioids are associated with increased rates of endocarditis compared to heroin, so it is also possible that the opioids injected by people with polysubstance use were different than those in the opioid-only group [38]. Multiple factors play into the risk of developing IDU-associated infections, including drug, socio-behavioral, and medical factors. Many of the preventive interventions provided by SSPs can help mitigate the risk of infection.

Patients with endocarditis, considered to be the most complicated infection of those evaluated—and universally fatal if untreated, were also most likely to leave the hospital prior to completing treatment. Many patients with IDU-associated infections and patient-directed discharge do not receive oral antibiotics to complete their treatment [11]; in one study, those who did not receive oral antibiotics upon patient-directed discharge had a 90-day readmission rate more than double of those with patient-directed discharge who did have an antibiotic prescribed (69% versus 33%) [39]. Avoidance of patient-directed discharge should be a top priority for patients with IDU-associated infections. A 9-point risk assessment tool has been shown to predict patients at risk for patient-directed discharge [40]. These data can be used to inform targeted interventions and focus on mitigating the factors that lead an individual patient to leave the hospital early. Treatment strategies should focus on implementing patient-centered care, informed by harm reduction principles, with a variety of treatment locations and modalities, including utilization of partial oral therapy for severe infections [39]. Additionally, integration of infectious disease and addiction treatment has the potential to address care that is often fragmented, by providing longitudinal support across the care continuum [41].

LIMITATIONS

Although we controlled for within-hospital correlation of subjects, prevalence of different substances used has geographically distinct patterns, which might explain the differences in outcomes identified. For example, as evidenced by the Florida Medical Examiner’s Report, there is considerable geographical variation in the state in terms of drugs found in decedents [42]. Thus, differences in demographics and outcomes could be explained by differences in local hospital and practice patterns, rather than being caused by the different substances injected themselves. Future investigations should evaluate IDU-associated infection differences in rural versus urban municipalities, which might explain the differences identified in this study and help to target SSP and addiction treatment resources to the regions with the most need.

Using ICD-10 codes has inherent limitations: there is no code specifically for IDU, so injection of drugs identified in the codes was an assumption. When multiple substances were present, the codes cannot account for which was injected. The ICD-10 code algorithm used in this study was previously validated and was 63% sensitive and 100% specific for identifying PWID among hospitalized patients, so the numbers in this study are likely an underestimate of the burden these infections in Florida [23]. As a retrospective cohort study based on administrative data, we cannot prove causality between different substances used and the outcomes evaluated. While we used statistical adjustments to address differences in demographic, comorbidity, and infections between the three substance use groups, we cannot rule out residual confounding. Additionally, due to the deidentified nature of the data, the same person may be represented multiple times in the cohort for different hospitalizations. Finally, other studies suggest that in-hospital mortality for IDU-associated infections is relatively low, but that intermediate to longer-term mortality is high [8, 43]. In this study, we were not able to link patients with posthospital mortality or readmission records.

CONCLUSIONS

In this retrospective cohort of all hospitalizations of PWID with IDU-associated infectious diseases over 2 years in Florida, we found notable differences in infectious complications and hospitalization outcomes when comparing opioid, stimulant, and opioid/stimulant use-associated infections. When categorized by substance used, those with opioid/stimulant use were younger, uninsured, more likely to have endocarditis, and most likely to have patient-directed discharge. The group who used stimulants only were most likely to experience in-hospital mortality. While many recent interventions have focused on mitigating the harms of injection opioid use by distributing naloxone and increasing access to MOUD, these data suggest that people who inject stimulants hospitalized with injection-related infections face unique challenges. Research investigating approaches to treating stimulant-associated infections, including medications for stimulant use disorder, is a high priority.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the clients and staff of the IDEA Exchange SSP who continuously inspire us to work to improve the wellbeing of people who use drugs. We also thank the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration for collection of this important data and for allowing the study team to access and analyze the data.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30CA240139. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.