-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shih-Yi Lin, Shu-Woei Ju, Cheng-Li Lin, Cheng-Chieh Lin, Wu-Huei Hsu, Chia-Hui Chou, Chih-Yu Chi, Chung-Y Hsu, Chia-Hung Kao, Risk of Viral Infection in Patients Using Either Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors or Angiotensin Receptor Blockers: A Nationwide Population-based Propensity Score Matching Study, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 71, Issue 10, 15 November 2020, Pages 2695–2701, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa734

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We hypothesized that renin–angiotensin system (RAS) blockers have systemic protective effects beyond the respiratory tract and could reduce the risk of viral infections.

We used the National Health Insurance Research Database and identified 2 study cohorts: the angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) cohort and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) cohort. Propensity score matching was applied at a 1:1 ratio by all associated variables to select 2 independent control cohorts for the ARB and ACEI cohorts. A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to assess the end outcome of viral infection.

The number of ARB and ACEI users was 20 207 and 18 029, respectively. The median age of ARB users and nonusers was 53.7 and 53.8 years, respectively. The median follow-up duration of ARB users and nonusers was 7.96 and 7.08 years; the median follow-up duration of ACEI users and nonusers was 8.70 and 8.98 years, respectively. The incidence rates of viral infections in ARB users and nonusers were 4.95 and 8.59 per 1000 person-years, respectively, and ARB users had a lower risk of viral infection than nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.53 [95% confidence interval {CI}, .48–.58]). The incidence rates of viral infections in ACEI users and nonusers were 6.10 per 1000 person-years and 7.72 per 1000 person-years, respectively, and ACEI users had a lower risk of viral infection than nonusers (aHR, 0.81 [95% CI, .74–.88]).

Hypertensive patients using either ARBs or ACEIs exhibit a lower risk of viral infection than nonusers.

A virus, defined as a microorganism consisting of only a nucleic acid and protein coat, causes many pathological diseases in humans, animals, and plants [1, 2]. Host factors and infective characteristics of a virus are the 2 major determinants of whether the virus is infectious to humans [3]. With advances in vaccine development, several viral diseases have become preventable and have been even eradicated [4–7]. Some studies have reported that in addition to vaccines, medications can modify the symptoms and invasiveness of viral infections [8–10]. Beasley et al indicated that acetaminophen use is an important risk factor for the development and/or maintenance of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in adolescents [10]. Graham et al also demonstrated that aspirin and acetaminophen use is associated with a longer duration of virus shedding in rhinovirus-infected people [8]. Antihypertensive medications of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are reported to show protective effects against the invasiveness, acute lung injury, and mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infection, although evidence is insufficient [11]. Meng et al have showed that using ACEIs or ARBs can potentially contribute to the improvement of clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients with hypertension [12]. Moreover, Perlot and Penninger reported that the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) could modulate innate immunity in the gut, of which ACE2 is necessary for the surface expression of the amino acid transporter; absence of ACE2 will cause inability absorption of amino acid, thus altered microbiota, which confers susceptibility to inflammation of the large intestine [13]. In addition, Li et al indicated that ACE2 and angiotensin (1-7) would cross-talk and inhibit JNK/NF-κB pathways to provide innate immunity and prevent infections [14]. ACEIs or ARBs may have systemic effects on innate immunity and viral infection risk. ACEI users were previously reported to show a low risk of pneumonia [15, 16]. However, large-scale population-based studies on the association between the use of either ACEIs or ARBs and the risk of viral infections affecting the whole body, except the lungs, are lacking. Therefore, we performed a nationwide population-based cohort study, in which we hypothesized that the use of ACEIs or ARBs demonstrates protective effects against viral infections beyond the lungs, and we applied propensity matching to test our hypothesis.

METHODS

Data Source

In 1995, Taiwan implemented the single-payer National Health Insurance program, and all deidentified claims data of this system were encrypted and released as the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). In this study, the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database, which comprises the data of 1 million beneficiaries randomly sampled from the NHIRD, was used. The Longitudinal Health Insurance Database contains medical information on ambulatory visits, inpatient hospitalizations, prescriptions, surgeries, and investigations. All diagnoses were coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital in Taiwan (CMUH104-REC2-115[CR4]).

Study Population

We enrolled patients with hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405). Four groups were identified, and the association between the use of ARBs or ACEIs and the risk of viral infections (ICD-9-CM codes 045–049, 055–056, 060–066, 071–079, and 460)(Appendix table 1), that is, ARB users and nonusers and ACEI users and nonusers—was assessed. The index date was defined as the date of the first diagnosis of hypertension. Patients diagnosed with viral infections before the index date and aged < 18 years old were excluded from the study. For comparison of ARB and ACEI users with the corresponding nonusers, propensity score through nearest neighbor matching (initially to the eighth digit and then as required to the first digit) was applied at a 1:1 ratio with those who did not use ARB and ACEI, by index year, age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications [17]. Therefore, matches were first made within a caliper width of 0.0000001, and then the caliper width was increased for unmatched cases to 0.1. We reconsidered the matching criteria and performed a rematch (greedy algorithm). For each hypertension patient on ARB and ACEI use, the corresponding comparisons were selected based on the nearest propensity score. The follow-up time ended when patients either developed a viral infection, died, withdrew from the National Health Insurance program, or 31 December 2013.

Comorbidities and Medications

Effects of comorbidities and medications were also considered. Comorbidities included hyperlipidemia, diabetes, rheumatoid disease, alcohol-related disease, asthma, transplantation, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease, congestive heart failure, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cancer, and stroke (Appendix table 1). Medications included prednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, azathioprine, α-blockers, β-blockers, potassium-sparing diuretics, thiazides, loop diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and other oral antihypertensive drugs.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of demographics, comorbidities, and medications are summarized by counts, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs) between the 4 groups. The χ 2 and Mann-Whitney tests were used to examine the differences in baseline distributions between ARB and ACEI users and nonusers. To calculate the cumulative incidence of viral infection as well as hospitalization due to viral infection and intubation due to viral infection, the Kaplan-Meier method was applied. The effect of frequency variation in drug use was considered as a time-dependent covariate, which was quantified every 6 months as a binary variable in the Cox proportional hazards model. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of viral infections were estimated in ARB and ACEI users compared with ARB and ACEI nonusers. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% CIs were estimated after adjusting for age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). The analyses were conducted with R programming. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The number of users of ARBs and ACEIs was 20 207 and 18 029, respectively. The median age of ARB users and nonusers was 53.7 (IQR, 45.9–63.9) years and 53.8 (IQR, 46.1–63.7) years, respectively, and that of ACEI users and nonusers was 53.3 (IQR, 45.7–63.8) years and 53.3 (IQR, 45.5–63.4) years, respectively. Approximately 39% of women and 61% of men used either ARBs or ACEIs. The distributions of urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications were not significantly different between ARB and ACEI users and nonusers (Table 1).

Demographic Characteristics and Comorbidities in the Propensity Score–Matched Cohorts With and Without Angiotensin Receptor Blockers or With and Without Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors Used in Patients With Hypertension

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | . | ACEI . | . | ||

| Variable . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n =20 207) . | P Valuea . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | P Valuea . |

| Age, y | .65 | .11 | ||||

| ≤ 49 | 7580 (37.5) | 7626 (37.7) | 7102 (39.4) | 7001 (38.8) | ||

| 50–64 | 8105 (40.1) | 8014 (39.7) | 7027 (39.0) | 6962 (38.6) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 4522 (22.4) | 4567 (22.6) | 3900 (21.6) | 4066 (22.3) | ||

| Median (IQR)b | 53.8 (46.1–63.7) | 53.7 (45.9–63.9) | .29 | 53.3 (45.5–63.4) | 53.3 (45.7–63.8) | .16 |

| Sex | .74 | .73 | ||||

| Female | 7912 (39.2) | 7879 (39.0) | 7023 (39.0) | 7055 (39.1) | ||

| Male | 12 295 (60.9) | 12 328 (61.0) | 11 006 (61.1) | 10 974 (60.9) | ||

| Urbanization levelc | .63 | .99 | ||||

| 1 (highest) | 6590 (32.6) | 6518 (32.3) | 5068 (28.1) | 5065 (28.1) | ||

| 2 | 5977 (29.6) | 5939 (29.4) | 5423 (30.0) | 5433 (30.1) | ||

| 3 | 3309 (16.4) | 3397 (16.8) | 3167 (17.6) | 3148 (17.5) | ||

| 4 (lowest) | 4331 (21.4) | 4353 (21.5) | 4371 (24.2) | 4383 (24.3) | ||

| Monthly income (NTD)d | .96 | .77 | ||||

| < 14 400 | 4471 (22.1) | 4509 (22.3) | 3884 (21.5) | 3962 (22.0) | ||

| 14 400–18 300 | 3766 (18.6) | 3743 (18.5) | 3270 (18.1) | 3267 (18.1) | ||

| 18 301–21 000 | 3674 (18.2) | 3684 (18.2) | 3356 (18.6) | 3354 (18.6) | ||

| > 21 000 | 8296 (41.1) | 8271 (40.9) | 7519 (41.7) | 7446 (41.3) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 9832 (48.7) | 9862 (48.8) | .77 | 8864 (49.2) | 8894 (49.3) | .75 |

| Diabetes | 3214 (15.9) | 3233 (16.0) | .80 | 3112 (17.3) | 3145 (17.4) | .65 |

| Rheumatoid disease | 61 (0.30) | 61 (0.30) | .99 | 59 (0.33) | 55 (0.31) | .71 |

| Alcohol-related disease | 1736 (8.59) | 1817 (8.99) | .15 | 1617 (8.97) | 1639 (9.09) | .69 |

| Asthma | 1777 (8.79) | 1790 (8.86) | .82 | 1547 (8.58) | 1597 (8.86) | .35 |

| Transplantation | 29 (0.14) | 25 (0.12) | .59 | 26 (0.14) | 21 (0.12) | .47 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4999 (24.7) | 5012 (24.8) | .88 | 4659 (25.8) | 4715 (26.2) | .50 |

| CKD or ESRD | 1380 (6.83) | 1416 (7.01) | .48 | 1293 (7.17) | 1294 (7.18) | .98 |

| COPD | 2793 (13.8) | 2854 (14.1) | .38 | 2558 (14.2) | 2599 (14.4) | .54 |

| HIV | 10 (0.05) | 11 (0.05) | .83 | 7 (0.04) | 7 (0.04) | .99 |

| Cancer | 1372 (6.79) | 1422 (7.04) | .33 | 1243 (6.89) | 1297 (7.19) | .27 |

| CHF | 1392 (6.89) | 1407 (6.96) | .77 | 1207 (6.69) | 1248 (6.92) | .39 |

| Stroke | 2226 (11.0) | 2177 (10.8) | .43 | 1833 (10.2) | 1934 (10.7) | .08 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Prednisolone | 13 985 (69.2) | 13 987 (69.2) | .98 | 12 452 (69.1) | 12 519 (69.4) | .44 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 36 (0.18) | 33 (0.16) | .72 | 29 (0.16) | 24 (0.13) | .49 |

| Cyclosporine | 49 (0.24) | 52 (0.26) | .77 | 54 (0.30) | 44 (0.24) | .31 |

| Tacrolimus | 28 (0.14) | 26 (0.13) | .79 | 26 (0.14) | 20 (0.11) | .38 |

| Azathioprine | 63 (0.31) | 70 (0.35) | .54 | 58 (0.32) | 54 (0.30) | .71 |

| Oral antihypertensive drugs | ||||||

| α-blockers | 4070 (20.1) | 4179 (20.7) | .18 | 3815 (21.2) | 3928 (21.8) | .15 |

| β-blockers | 13 256 (65.6) | 13 357 (66.1) | .29 | 12 109 (67.2) | 12 249 (67.9) | .12 |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 3479 (17.2) | 3450 (17.1) | .70 | 3208 (17.8) | 3284 (18.2) | .30 |

| Thiazides | 12 225 (60.5) | 12 337 (61.1) | .25 | 11 172 (62.0) | 11 203 (62.1) | .74 |

| Loop diuretics | 6656 (32.9) | 6658 (33.0) | .98 | 6005 (33.3) | 6177 (34.3) | .06 |

| CCB (non-DHP or DHP) | 17 631 (87.3) | 17 548 (86.8) | .22 | 15 572 (86.4) | 15 582 (86.4) | .88 |

| ACEI | 6765 (33.5) | 6908 (34.2) | .13 | |||

| ARB | 9608 (53.3) | 9712 (53.9) | .27 | |||

| Others | 3589 (17.8) | 3534 (17.5) | .47 | 3461 (19.2) | 3471 (19.3) | .89 |

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | . | ACEI . | . | ||

| Variable . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n =20 207) . | P Valuea . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | P Valuea . |

| Age, y | .65 | .11 | ||||

| ≤ 49 | 7580 (37.5) | 7626 (37.7) | 7102 (39.4) | 7001 (38.8) | ||

| 50–64 | 8105 (40.1) | 8014 (39.7) | 7027 (39.0) | 6962 (38.6) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 4522 (22.4) | 4567 (22.6) | 3900 (21.6) | 4066 (22.3) | ||

| Median (IQR)b | 53.8 (46.1–63.7) | 53.7 (45.9–63.9) | .29 | 53.3 (45.5–63.4) | 53.3 (45.7–63.8) | .16 |

| Sex | .74 | .73 | ||||

| Female | 7912 (39.2) | 7879 (39.0) | 7023 (39.0) | 7055 (39.1) | ||

| Male | 12 295 (60.9) | 12 328 (61.0) | 11 006 (61.1) | 10 974 (60.9) | ||

| Urbanization levelc | .63 | .99 | ||||

| 1 (highest) | 6590 (32.6) | 6518 (32.3) | 5068 (28.1) | 5065 (28.1) | ||

| 2 | 5977 (29.6) | 5939 (29.4) | 5423 (30.0) | 5433 (30.1) | ||

| 3 | 3309 (16.4) | 3397 (16.8) | 3167 (17.6) | 3148 (17.5) | ||

| 4 (lowest) | 4331 (21.4) | 4353 (21.5) | 4371 (24.2) | 4383 (24.3) | ||

| Monthly income (NTD)d | .96 | .77 | ||||

| < 14 400 | 4471 (22.1) | 4509 (22.3) | 3884 (21.5) | 3962 (22.0) | ||

| 14 400–18 300 | 3766 (18.6) | 3743 (18.5) | 3270 (18.1) | 3267 (18.1) | ||

| 18 301–21 000 | 3674 (18.2) | 3684 (18.2) | 3356 (18.6) | 3354 (18.6) | ||

| > 21 000 | 8296 (41.1) | 8271 (40.9) | 7519 (41.7) | 7446 (41.3) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 9832 (48.7) | 9862 (48.8) | .77 | 8864 (49.2) | 8894 (49.3) | .75 |

| Diabetes | 3214 (15.9) | 3233 (16.0) | .80 | 3112 (17.3) | 3145 (17.4) | .65 |

| Rheumatoid disease | 61 (0.30) | 61 (0.30) | .99 | 59 (0.33) | 55 (0.31) | .71 |

| Alcohol-related disease | 1736 (8.59) | 1817 (8.99) | .15 | 1617 (8.97) | 1639 (9.09) | .69 |

| Asthma | 1777 (8.79) | 1790 (8.86) | .82 | 1547 (8.58) | 1597 (8.86) | .35 |

| Transplantation | 29 (0.14) | 25 (0.12) | .59 | 26 (0.14) | 21 (0.12) | .47 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4999 (24.7) | 5012 (24.8) | .88 | 4659 (25.8) | 4715 (26.2) | .50 |

| CKD or ESRD | 1380 (6.83) | 1416 (7.01) | .48 | 1293 (7.17) | 1294 (7.18) | .98 |

| COPD | 2793 (13.8) | 2854 (14.1) | .38 | 2558 (14.2) | 2599 (14.4) | .54 |

| HIV | 10 (0.05) | 11 (0.05) | .83 | 7 (0.04) | 7 (0.04) | .99 |

| Cancer | 1372 (6.79) | 1422 (7.04) | .33 | 1243 (6.89) | 1297 (7.19) | .27 |

| CHF | 1392 (6.89) | 1407 (6.96) | .77 | 1207 (6.69) | 1248 (6.92) | .39 |

| Stroke | 2226 (11.0) | 2177 (10.8) | .43 | 1833 (10.2) | 1934 (10.7) | .08 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Prednisolone | 13 985 (69.2) | 13 987 (69.2) | .98 | 12 452 (69.1) | 12 519 (69.4) | .44 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 36 (0.18) | 33 (0.16) | .72 | 29 (0.16) | 24 (0.13) | .49 |

| Cyclosporine | 49 (0.24) | 52 (0.26) | .77 | 54 (0.30) | 44 (0.24) | .31 |

| Tacrolimus | 28 (0.14) | 26 (0.13) | .79 | 26 (0.14) | 20 (0.11) | .38 |

| Azathioprine | 63 (0.31) | 70 (0.35) | .54 | 58 (0.32) | 54 (0.30) | .71 |

| Oral antihypertensive drugs | ||||||

| α-blockers | 4070 (20.1) | 4179 (20.7) | .18 | 3815 (21.2) | 3928 (21.8) | .15 |

| β-blockers | 13 256 (65.6) | 13 357 (66.1) | .29 | 12 109 (67.2) | 12 249 (67.9) | .12 |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 3479 (17.2) | 3450 (17.1) | .70 | 3208 (17.8) | 3284 (18.2) | .30 |

| Thiazides | 12 225 (60.5) | 12 337 (61.1) | .25 | 11 172 (62.0) | 11 203 (62.1) | .74 |

| Loop diuretics | 6656 (32.9) | 6658 (33.0) | .98 | 6005 (33.3) | 6177 (34.3) | .06 |

| CCB (non-DHP or DHP) | 17 631 (87.3) | 17 548 (86.8) | .22 | 15 572 (86.4) | 15 582 (86.4) | .88 |

| ACEI | 6765 (33.5) | 6908 (34.2) | .13 | |||

| ARB | 9608 (53.3) | 9712 (53.9) | .27 | |||

| Others | 3589 (17.8) | 3534 (17.5) | .47 | 3461 (19.2) | 3471 (19.3) | .89 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney diseases; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHP, dihydropyridine; ESRD, end stage renal disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; NTD, new Taiwan dollar.

aP Value means χ 2 test.

bMann-Whitney test.

cUrbanization level was categorized by the population density of the residential area into 4 levels, with level 1 as the most urbanized and level 4 as the least urbanized.

dOne NTD is equal to 0.03 United States dollars.

Demographic Characteristics and Comorbidities in the Propensity Score–Matched Cohorts With and Without Angiotensin Receptor Blockers or With and Without Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors Used in Patients With Hypertension

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | . | ACEI . | . | ||

| Variable . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n =20 207) . | P Valuea . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | P Valuea . |

| Age, y | .65 | .11 | ||||

| ≤ 49 | 7580 (37.5) | 7626 (37.7) | 7102 (39.4) | 7001 (38.8) | ||

| 50–64 | 8105 (40.1) | 8014 (39.7) | 7027 (39.0) | 6962 (38.6) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 4522 (22.4) | 4567 (22.6) | 3900 (21.6) | 4066 (22.3) | ||

| Median (IQR)b | 53.8 (46.1–63.7) | 53.7 (45.9–63.9) | .29 | 53.3 (45.5–63.4) | 53.3 (45.7–63.8) | .16 |

| Sex | .74 | .73 | ||||

| Female | 7912 (39.2) | 7879 (39.0) | 7023 (39.0) | 7055 (39.1) | ||

| Male | 12 295 (60.9) | 12 328 (61.0) | 11 006 (61.1) | 10 974 (60.9) | ||

| Urbanization levelc | .63 | .99 | ||||

| 1 (highest) | 6590 (32.6) | 6518 (32.3) | 5068 (28.1) | 5065 (28.1) | ||

| 2 | 5977 (29.6) | 5939 (29.4) | 5423 (30.0) | 5433 (30.1) | ||

| 3 | 3309 (16.4) | 3397 (16.8) | 3167 (17.6) | 3148 (17.5) | ||

| 4 (lowest) | 4331 (21.4) | 4353 (21.5) | 4371 (24.2) | 4383 (24.3) | ||

| Monthly income (NTD)d | .96 | .77 | ||||

| < 14 400 | 4471 (22.1) | 4509 (22.3) | 3884 (21.5) | 3962 (22.0) | ||

| 14 400–18 300 | 3766 (18.6) | 3743 (18.5) | 3270 (18.1) | 3267 (18.1) | ||

| 18 301–21 000 | 3674 (18.2) | 3684 (18.2) | 3356 (18.6) | 3354 (18.6) | ||

| > 21 000 | 8296 (41.1) | 8271 (40.9) | 7519 (41.7) | 7446 (41.3) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 9832 (48.7) | 9862 (48.8) | .77 | 8864 (49.2) | 8894 (49.3) | .75 |

| Diabetes | 3214 (15.9) | 3233 (16.0) | .80 | 3112 (17.3) | 3145 (17.4) | .65 |

| Rheumatoid disease | 61 (0.30) | 61 (0.30) | .99 | 59 (0.33) | 55 (0.31) | .71 |

| Alcohol-related disease | 1736 (8.59) | 1817 (8.99) | .15 | 1617 (8.97) | 1639 (9.09) | .69 |

| Asthma | 1777 (8.79) | 1790 (8.86) | .82 | 1547 (8.58) | 1597 (8.86) | .35 |

| Transplantation | 29 (0.14) | 25 (0.12) | .59 | 26 (0.14) | 21 (0.12) | .47 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4999 (24.7) | 5012 (24.8) | .88 | 4659 (25.8) | 4715 (26.2) | .50 |

| CKD or ESRD | 1380 (6.83) | 1416 (7.01) | .48 | 1293 (7.17) | 1294 (7.18) | .98 |

| COPD | 2793 (13.8) | 2854 (14.1) | .38 | 2558 (14.2) | 2599 (14.4) | .54 |

| HIV | 10 (0.05) | 11 (0.05) | .83 | 7 (0.04) | 7 (0.04) | .99 |

| Cancer | 1372 (6.79) | 1422 (7.04) | .33 | 1243 (6.89) | 1297 (7.19) | .27 |

| CHF | 1392 (6.89) | 1407 (6.96) | .77 | 1207 (6.69) | 1248 (6.92) | .39 |

| Stroke | 2226 (11.0) | 2177 (10.8) | .43 | 1833 (10.2) | 1934 (10.7) | .08 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Prednisolone | 13 985 (69.2) | 13 987 (69.2) | .98 | 12 452 (69.1) | 12 519 (69.4) | .44 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 36 (0.18) | 33 (0.16) | .72 | 29 (0.16) | 24 (0.13) | .49 |

| Cyclosporine | 49 (0.24) | 52 (0.26) | .77 | 54 (0.30) | 44 (0.24) | .31 |

| Tacrolimus | 28 (0.14) | 26 (0.13) | .79 | 26 (0.14) | 20 (0.11) | .38 |

| Azathioprine | 63 (0.31) | 70 (0.35) | .54 | 58 (0.32) | 54 (0.30) | .71 |

| Oral antihypertensive drugs | ||||||

| α-blockers | 4070 (20.1) | 4179 (20.7) | .18 | 3815 (21.2) | 3928 (21.8) | .15 |

| β-blockers | 13 256 (65.6) | 13 357 (66.1) | .29 | 12 109 (67.2) | 12 249 (67.9) | .12 |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 3479 (17.2) | 3450 (17.1) | .70 | 3208 (17.8) | 3284 (18.2) | .30 |

| Thiazides | 12 225 (60.5) | 12 337 (61.1) | .25 | 11 172 (62.0) | 11 203 (62.1) | .74 |

| Loop diuretics | 6656 (32.9) | 6658 (33.0) | .98 | 6005 (33.3) | 6177 (34.3) | .06 |

| CCB (non-DHP or DHP) | 17 631 (87.3) | 17 548 (86.8) | .22 | 15 572 (86.4) | 15 582 (86.4) | .88 |

| ACEI | 6765 (33.5) | 6908 (34.2) | .13 | |||

| ARB | 9608 (53.3) | 9712 (53.9) | .27 | |||

| Others | 3589 (17.8) | 3534 (17.5) | .47 | 3461 (19.2) | 3471 (19.3) | .89 |

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | Propensity Score Matched . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | . | ACEI . | . | ||

| Variable . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n =20 207) . | P Valuea . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | P Valuea . |

| Age, y | .65 | .11 | ||||

| ≤ 49 | 7580 (37.5) | 7626 (37.7) | 7102 (39.4) | 7001 (38.8) | ||

| 50–64 | 8105 (40.1) | 8014 (39.7) | 7027 (39.0) | 6962 (38.6) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 4522 (22.4) | 4567 (22.6) | 3900 (21.6) | 4066 (22.3) | ||

| Median (IQR)b | 53.8 (46.1–63.7) | 53.7 (45.9–63.9) | .29 | 53.3 (45.5–63.4) | 53.3 (45.7–63.8) | .16 |

| Sex | .74 | .73 | ||||

| Female | 7912 (39.2) | 7879 (39.0) | 7023 (39.0) | 7055 (39.1) | ||

| Male | 12 295 (60.9) | 12 328 (61.0) | 11 006 (61.1) | 10 974 (60.9) | ||

| Urbanization levelc | .63 | .99 | ||||

| 1 (highest) | 6590 (32.6) | 6518 (32.3) | 5068 (28.1) | 5065 (28.1) | ||

| 2 | 5977 (29.6) | 5939 (29.4) | 5423 (30.0) | 5433 (30.1) | ||

| 3 | 3309 (16.4) | 3397 (16.8) | 3167 (17.6) | 3148 (17.5) | ||

| 4 (lowest) | 4331 (21.4) | 4353 (21.5) | 4371 (24.2) | 4383 (24.3) | ||

| Monthly income (NTD)d | .96 | .77 | ||||

| < 14 400 | 4471 (22.1) | 4509 (22.3) | 3884 (21.5) | 3962 (22.0) | ||

| 14 400–18 300 | 3766 (18.6) | 3743 (18.5) | 3270 (18.1) | 3267 (18.1) | ||

| 18 301–21 000 | 3674 (18.2) | 3684 (18.2) | 3356 (18.6) | 3354 (18.6) | ||

| > 21 000 | 8296 (41.1) | 8271 (40.9) | 7519 (41.7) | 7446 (41.3) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 9832 (48.7) | 9862 (48.8) | .77 | 8864 (49.2) | 8894 (49.3) | .75 |

| Diabetes | 3214 (15.9) | 3233 (16.0) | .80 | 3112 (17.3) | 3145 (17.4) | .65 |

| Rheumatoid disease | 61 (0.30) | 61 (0.30) | .99 | 59 (0.33) | 55 (0.31) | .71 |

| Alcohol-related disease | 1736 (8.59) | 1817 (8.99) | .15 | 1617 (8.97) | 1639 (9.09) | .69 |

| Asthma | 1777 (8.79) | 1790 (8.86) | .82 | 1547 (8.58) | 1597 (8.86) | .35 |

| Transplantation | 29 (0.14) | 25 (0.12) | .59 | 26 (0.14) | 21 (0.12) | .47 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4999 (24.7) | 5012 (24.8) | .88 | 4659 (25.8) | 4715 (26.2) | .50 |

| CKD or ESRD | 1380 (6.83) | 1416 (7.01) | .48 | 1293 (7.17) | 1294 (7.18) | .98 |

| COPD | 2793 (13.8) | 2854 (14.1) | .38 | 2558 (14.2) | 2599 (14.4) | .54 |

| HIV | 10 (0.05) | 11 (0.05) | .83 | 7 (0.04) | 7 (0.04) | .99 |

| Cancer | 1372 (6.79) | 1422 (7.04) | .33 | 1243 (6.89) | 1297 (7.19) | .27 |

| CHF | 1392 (6.89) | 1407 (6.96) | .77 | 1207 (6.69) | 1248 (6.92) | .39 |

| Stroke | 2226 (11.0) | 2177 (10.8) | .43 | 1833 (10.2) | 1934 (10.7) | .08 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Prednisolone | 13 985 (69.2) | 13 987 (69.2) | .98 | 12 452 (69.1) | 12 519 (69.4) | .44 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 36 (0.18) | 33 (0.16) | .72 | 29 (0.16) | 24 (0.13) | .49 |

| Cyclosporine | 49 (0.24) | 52 (0.26) | .77 | 54 (0.30) | 44 (0.24) | .31 |

| Tacrolimus | 28 (0.14) | 26 (0.13) | .79 | 26 (0.14) | 20 (0.11) | .38 |

| Azathioprine | 63 (0.31) | 70 (0.35) | .54 | 58 (0.32) | 54 (0.30) | .71 |

| Oral antihypertensive drugs | ||||||

| α-blockers | 4070 (20.1) | 4179 (20.7) | .18 | 3815 (21.2) | 3928 (21.8) | .15 |

| β-blockers | 13 256 (65.6) | 13 357 (66.1) | .29 | 12 109 (67.2) | 12 249 (67.9) | .12 |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 3479 (17.2) | 3450 (17.1) | .70 | 3208 (17.8) | 3284 (18.2) | .30 |

| Thiazides | 12 225 (60.5) | 12 337 (61.1) | .25 | 11 172 (62.0) | 11 203 (62.1) | .74 |

| Loop diuretics | 6656 (32.9) | 6658 (33.0) | .98 | 6005 (33.3) | 6177 (34.3) | .06 |

| CCB (non-DHP or DHP) | 17 631 (87.3) | 17 548 (86.8) | .22 | 15 572 (86.4) | 15 582 (86.4) | .88 |

| ACEI | 6765 (33.5) | 6908 (34.2) | .13 | |||

| ARB | 9608 (53.3) | 9712 (53.9) | .27 | |||

| Others | 3589 (17.8) | 3534 (17.5) | .47 | 3461 (19.2) | 3471 (19.3) | .89 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney diseases; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHP, dihydropyridine; ESRD, end stage renal disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; NTD, new Taiwan dollar.

aP Value means χ 2 test.

bMann-Whitney test.

cUrbanization level was categorized by the population density of the residential area into 4 levels, with level 1 as the most urbanized and level 4 as the least urbanized.

dOne NTD is equal to 0.03 United States dollars.

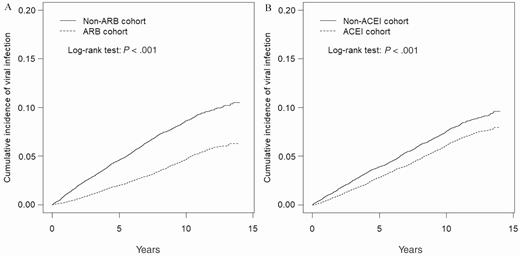

The cumulative incidence of viral infections in ARB and ACEI users was significantly lower than that in the nonusers (ARB, P < .001; ACEI, P < .001; Figure 1A and 1B). The median follow-up duration in ARB users and nonusers was 7.96 (IQR, 4.70–11.0) years and 7.08 (IQR, 3.87–10.4) years, respectively, and that in ACEI users and nonusers was 8.70 (IQR, 5.07–11.5) years and 8.98 (IQR, 5.77–11.6) years, respectively. The incidence rate of viral infections in ARB users and nonusers was 4.59 per 1000 person-years and 8.95 per 1000 person-years, respectively, and ARB users had a lower risk of viral infections than ARB nonusers (aHR, 0.53 [95% CI, .48–.58]); the incidence rate of viral infections in ACEI users and nonusers was 6.10 per 1000 person-years and 7.72 per 1000 person-years, respectively, and ACEI users had a lower risk of viral infections than ACEI nonusers (aHR, 0.81 [95% CI, .74–.88]) (Table 2). ARB users had a lower risk of hospitalization due to viral infection than ARB nonusers (aHR, 0.59 [95% CI, .42–.83]).

Cumulative incidence curves of viral infection for angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) users and ARB nonusers (A) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) users and ACEI nonusers (B) by propensity score matching.

Incidence (per 1000 Person-years) and Hazard Ratios of Viral Infection in the Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) or Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI) Cohorts Compared With Those in the Non-ARB or Non-ACEI Cohorts by Cox Proportional Hazard Models With Time-dependent Exposure Covariates in Patients With Hypertension

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||

| Characteristic . | No (N = 20 207) . | Yes (N = 20 207) . | No (N = 18 029) . | Yes (N = 18 029) . |

| Person-years | ||||

| Follow-up time, y, median (IQR) | 7.08 (3.87–10.4) | 7.96 (4.70–11.0) | 8.70 (5.07–11.5) | 8.98 (5.77–11.6) |

| Viral infection | ||||

| Event | 1301 | 723 | 1142 | 937 |

| Ratea | 8.95 | 4.59 | 7.72 | 6.10 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.51 (.47–.56)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.79 (.72–.86)*** |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.53 (.48–.58)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.74–.88)*** |

| Hospitalization due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 84 | 55 | 71 | 65 |

| Ratea | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.42 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.61 (.43–.86)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.88 (.63–1.24) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.59 (.42–.83)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.89 (.63–1.25) |

| Intubation due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 10 | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| Ratea | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.37 (.12–1.18) | 1 (Reference) | 0.87 (.35–2.13) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.32 (.10–1.07) | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.32–2.03) |

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||

| Characteristic . | No (N = 20 207) . | Yes (N = 20 207) . | No (N = 18 029) . | Yes (N = 18 029) . |

| Person-years | ||||

| Follow-up time, y, median (IQR) | 7.08 (3.87–10.4) | 7.96 (4.70–11.0) | 8.70 (5.07–11.5) | 8.98 (5.77–11.6) |

| Viral infection | ||||

| Event | 1301 | 723 | 1142 | 937 |

| Ratea | 8.95 | 4.59 | 7.72 | 6.10 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.51 (.47–.56)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.79 (.72–.86)*** |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.53 (.48–.58)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.74–.88)*** |

| Hospitalization due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 84 | 55 | 71 | 65 |

| Ratea | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.42 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.61 (.43–.86)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.88 (.63–1.24) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.59 (.42–.83)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.89 (.63–1.25) |

| Intubation due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 10 | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| Ratea | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.37 (.12–1.18) | 1 (Reference) | 0.87 (.35–2.13) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.32 (.10–1.07) | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.32–2.03) |

Crude HR, relative; adjusted HR, multivariable analysis including age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications.

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

aIncidence rate per 1000 person-years.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Incidence (per 1000 Person-years) and Hazard Ratios of Viral Infection in the Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) or Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI) Cohorts Compared With Those in the Non-ARB or Non-ACEI Cohorts by Cox Proportional Hazard Models With Time-dependent Exposure Covariates in Patients With Hypertension

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||

| Characteristic . | No (N = 20 207) . | Yes (N = 20 207) . | No (N = 18 029) . | Yes (N = 18 029) . |

| Person-years | ||||

| Follow-up time, y, median (IQR) | 7.08 (3.87–10.4) | 7.96 (4.70–11.0) | 8.70 (5.07–11.5) | 8.98 (5.77–11.6) |

| Viral infection | ||||

| Event | 1301 | 723 | 1142 | 937 |

| Ratea | 8.95 | 4.59 | 7.72 | 6.10 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.51 (.47–.56)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.79 (.72–.86)*** |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.53 (.48–.58)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.74–.88)*** |

| Hospitalization due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 84 | 55 | 71 | 65 |

| Ratea | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.42 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.61 (.43–.86)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.88 (.63–1.24) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.59 (.42–.83)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.89 (.63–1.25) |

| Intubation due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 10 | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| Ratea | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.37 (.12–1.18) | 1 (Reference) | 0.87 (.35–2.13) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.32 (.10–1.07) | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.32–2.03) |

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||

| Characteristic . | No (N = 20 207) . | Yes (N = 20 207) . | No (N = 18 029) . | Yes (N = 18 029) . |

| Person-years | ||||

| Follow-up time, y, median (IQR) | 7.08 (3.87–10.4) | 7.96 (4.70–11.0) | 8.70 (5.07–11.5) | 8.98 (5.77–11.6) |

| Viral infection | ||||

| Event | 1301 | 723 | 1142 | 937 |

| Ratea | 8.95 | 4.59 | 7.72 | 6.10 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.51 (.47–.56)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.79 (.72–.86)*** |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.53 (.48–.58)*** | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.74–.88)*** |

| Hospitalization due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 84 | 55 | 71 | 65 |

| Ratea | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.42 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.61 (.43–.86)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.88 (.63–1.24) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.59 (.42–.83)** | 1 (Reference) | 0.89 (.63–1.25) |

| Intubation due to viral infection | ||||

| Event | 10 | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| Ratea | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.37 (.12–1.18) | 1 (Reference) | 0.87 (.35–2.13) |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (Reference) | 0.32 (.10–1.07) | 1 (Reference) | 0.81 (.32–2.03) |

Crude HR, relative; adjusted HR, multivariable analysis including age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications.

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

aIncidence rate per 1000 person-years.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

In subgroup analyses, ARB users had a significantly decreased incidence of viral infections compared with ARB nonusers at any subgroup level (aHR, 0.54 [95% CI, .47–.62] in age ≤ 49 years; aHR, 0.53 [95% CI, .46–.61] in age 50–64 years; aHR, 0.52 [95% CI, .42–.64] in age ≥ 65 years; aHR, 0.49 [95% CI, .43–.57] in women; aHR, 0.56 [95% CI, .50–.63] in men). ACEI users also had a significantly decreased incidence of viral infection compared with ACEI nonusers at any subgroup level (aHR, 0.80 [95% CI, .70–.91] in age ≤ 49 years; aHR, 0.82 [95% CI, .71–.94] in age 50–64 years; aHR, 0.81 [95% CI, .66–.99] in age ≥ 65 years; aHR, 0.77 [95% CI, .67–.89] in women; aHR, 0.83 [95% CI, .74–.93] in men) (Table 3).

Incidence and Hazard Ratios of Viral Infection Measured by Age, Sex, and Comorbidity in the Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) or Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI) Cohorts Compared With Those in the Non-ARB or Non-ACEI Cohorts by Cox Proportional Hazard Models With Time-dependent Exposure Covariates in Patients With Hypertension

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||||||||

| . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n = 20 207) . | . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | . | ||||

| Variable . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| ≤ 49 | 545 | 9.43 | 297 | 4.88 | 0.54 (.47–.62)*** | 498 | 8.20 | 395 | 6.44 | 0.80 (.70–.91)*** |

| 50–64 | 513 | 8.87 | 281 | 4.57 | 0.53 (.46–.61)*** | 442 | 7.64 | 359 | 6.10 | 0.82 (.71–.94)** |

| ≥ 65 | 243 | 8.21 | 145 | 4.15 | 0.52 (.42–.64)*** | 202 | 6.90 | 183 | 5.47 | 0.81 (.66–.99)* |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 548 | 9.18 | 278 | 4.32 | 0.49 (.43–.57)*** | 562 | 9.49 | 269 | 4.19 | 0.77 (.67–.89)*** |

| Male | 753 | 8.79 | 445 | 4.78 | 0.56 (.50–.63)*** | 782 | 9.97 | 466 | 4.67 | 0.83 (.74–.93)** |

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||||||||

| . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n = 20 207) . | . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | . | ||||

| Variable . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| ≤ 49 | 545 | 9.43 | 297 | 4.88 | 0.54 (.47–.62)*** | 498 | 8.20 | 395 | 6.44 | 0.80 (.70–.91)*** |

| 50–64 | 513 | 8.87 | 281 | 4.57 | 0.53 (.46–.61)*** | 442 | 7.64 | 359 | 6.10 | 0.82 (.71–.94)** |

| ≥ 65 | 243 | 8.21 | 145 | 4.15 | 0.52 (.42–.64)*** | 202 | 6.90 | 183 | 5.47 | 0.81 (.66–.99)* |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 548 | 9.18 | 278 | 4.32 | 0.49 (.43–.57)*** | 562 | 9.49 | 269 | 4.19 | 0.77 (.67–.89)*** |

| Male | 753 | 8.79 | 445 | 4.78 | 0.56 (.50–.63)*** | 782 | 9.97 | 466 | 4.67 | 0.83 (.74–.93)** |

Rate is incidence rate per 1000 person-years; crude HR, relative; adjusted HR, multivariable analysis including age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications.

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Incidence and Hazard Ratios of Viral Infection Measured by Age, Sex, and Comorbidity in the Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) or Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI) Cohorts Compared With Those in the Non-ARB or Non-ACEI Cohorts by Cox Proportional Hazard Models With Time-dependent Exposure Covariates in Patients With Hypertension

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||||||||

| . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n = 20 207) . | . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | . | ||||

| Variable . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| ≤ 49 | 545 | 9.43 | 297 | 4.88 | 0.54 (.47–.62)*** | 498 | 8.20 | 395 | 6.44 | 0.80 (.70–.91)*** |

| 50–64 | 513 | 8.87 | 281 | 4.57 | 0.53 (.46–.61)*** | 442 | 7.64 | 359 | 6.10 | 0.82 (.71–.94)** |

| ≥ 65 | 243 | 8.21 | 145 | 4.15 | 0.52 (.42–.64)*** | 202 | 6.90 | 183 | 5.47 | 0.81 (.66–.99)* |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 548 | 9.18 | 278 | 4.32 | 0.49 (.43–.57)*** | 562 | 9.49 | 269 | 4.19 | 0.77 (.67–.89)*** |

| Male | 753 | 8.79 | 445 | 4.78 | 0.56 (.50–.63)*** | 782 | 9.97 | 466 | 4.67 | 0.83 (.74–.93)** |

| . | Propensity Score Matched . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | ARB . | ACEI . | ||||||||

| . | No (n = 20 207) . | Yes (n = 20 207) . | . | No (n = 18 029) . | Yes (n = 18 029) . | . | ||||

| Variable . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . | Event . | Rate . | Event . | Rate . | Adjusted HR (95% CI) . |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| ≤ 49 | 545 | 9.43 | 297 | 4.88 | 0.54 (.47–.62)*** | 498 | 8.20 | 395 | 6.44 | 0.80 (.70–.91)*** |

| 50–64 | 513 | 8.87 | 281 | 4.57 | 0.53 (.46–.61)*** | 442 | 7.64 | 359 | 6.10 | 0.82 (.71–.94)** |

| ≥ 65 | 243 | 8.21 | 145 | 4.15 | 0.52 (.42–.64)*** | 202 | 6.90 | 183 | 5.47 | 0.81 (.66–.99)* |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 548 | 9.18 | 278 | 4.32 | 0.49 (.43–.57)*** | 562 | 9.49 | 269 | 4.19 | 0.77 (.67–.89)*** |

| Male | 753 | 8.79 | 445 | 4.78 | 0.56 (.50–.63)*** | 782 | 9.97 | 466 | 4.67 | 0.83 (.74–.93)** |

Rate is incidence rate per 1000 person-years; crude HR, relative; adjusted HR, multivariable analysis including age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications.

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Compared with ARB nonusers, hypertensive patients using ARBs for a longer duration were at a lower risk of viral infections (aHR, 0.82 [95% CI, .70–.96] for ≤ 120 days; aHR, 0.70 [95% CI, .61–.80] for 121–500 days; aHR, 0.47 [95% CI, .40–.55] for 501–1200 days; aHR, 0.31 [95% CI, .26–.37] for > 1200 days). Compared with ACEI nonusers, hypertensive patients using ACEIs for a longer duration were also at a lower risk of viral infections (aHR, 0.87 [95% CI, .76–1.00] for 151–550 days; aHR, 0.50 [95% CI, .43–.59] for > 550 days) (Table 4).

Incidence and Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Viral Infection Stratified by Duration of Angiotensin Receptor Blocker or Angiotensin-converting-Enzyme Inhibitor Therapy in Patients With Hypertension

| Medication Exposed . | No. . | Event . | Person-years . | Ratea . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARBc | |||||

| Non-ARB | 20 207 | 1301 | 145 307 | 8.95 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 120 d | 3792 | 192 | 26 017 | 7.38 | 0.82 (.70–.96)* |

| 121–500 d | 5499 | 225 | 37 708 | 5.97 | 0.70 (.61–.80)*** |

| 500–1200 d | 5315 | 158 | 39 873 | 3.96 | 0.47 (.40–.55)*** |

| > 1200 d | 5601 | 148 | 53 809 | 2.75 | 0.31 (.26–.37)*** |

| ACEIc | |||||

| Non-ACEI | 18 029 | 1142 | 147 866 | 7.72 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 50 d | 2535 | 195 | 20 430 | 9.54 | 1.23 (1.05–1.43)** |

| 51–150 d | 5254 | 293 | 42 918 | 6.83 | 0.92 (.81–1.04) |

| 151–550 d | 5091 | 259 | 42 409 | 6.11 | 0.87 (.76–1.00)* |

| > 550 d | 5149 | 190 | 47 880 | 3.97 | 0.50 (.43–.59)*** |

| Medication Exposed . | No. . | Event . | Person-years . | Ratea . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARBc | |||||

| Non-ARB | 20 207 | 1301 | 145 307 | 8.95 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 120 d | 3792 | 192 | 26 017 | 7.38 | 0.82 (.70–.96)* |

| 121–500 d | 5499 | 225 | 37 708 | 5.97 | 0.70 (.61–.80)*** |

| 500–1200 d | 5315 | 158 | 39 873 | 3.96 | 0.47 (.40–.55)*** |

| > 1200 d | 5601 | 148 | 53 809 | 2.75 | 0.31 (.26–.37)*** |

| ACEIc | |||||

| Non-ACEI | 18 029 | 1142 | 147 866 | 7.72 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 50 d | 2535 | 195 | 20 430 | 9.54 | 1.23 (1.05–1.43)** |

| 51–150 d | 5254 | 293 | 42 918 | 6.83 | 0.92 (.81–1.04) |

| 151–550 d | 5091 | 259 | 42 409 | 6.11 | 0.87 (.76–1.00)* |

| > 550 d | 5149 | 190 | 47 880 | 3.97 | 0.50 (.43–.59)*** |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

aRate is incidence rate per 1000 person-years.

bMultivariable analysis including age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications.

cThe cumulative use days are partitioned in to 4 segments by quartile.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Incidence and Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Viral Infection Stratified by Duration of Angiotensin Receptor Blocker or Angiotensin-converting-Enzyme Inhibitor Therapy in Patients With Hypertension

| Medication Exposed . | No. . | Event . | Person-years . | Ratea . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARBc | |||||

| Non-ARB | 20 207 | 1301 | 145 307 | 8.95 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 120 d | 3792 | 192 | 26 017 | 7.38 | 0.82 (.70–.96)* |

| 121–500 d | 5499 | 225 | 37 708 | 5.97 | 0.70 (.61–.80)*** |

| 500–1200 d | 5315 | 158 | 39 873 | 3.96 | 0.47 (.40–.55)*** |

| > 1200 d | 5601 | 148 | 53 809 | 2.75 | 0.31 (.26–.37)*** |

| ACEIc | |||||

| Non-ACEI | 18 029 | 1142 | 147 866 | 7.72 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 50 d | 2535 | 195 | 20 430 | 9.54 | 1.23 (1.05–1.43)** |

| 51–150 d | 5254 | 293 | 42 918 | 6.83 | 0.92 (.81–1.04) |

| 151–550 d | 5091 | 259 | 42 409 | 6.11 | 0.87 (.76–1.00)* |

| > 550 d | 5149 | 190 | 47 880 | 3.97 | 0.50 (.43–.59)*** |

| Medication Exposed . | No. . | Event . | Person-years . | Ratea . | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARBc | |||||

| Non-ARB | 20 207 | 1301 | 145 307 | 8.95 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 120 d | 3792 | 192 | 26 017 | 7.38 | 0.82 (.70–.96)* |

| 121–500 d | 5499 | 225 | 37 708 | 5.97 | 0.70 (.61–.80)*** |

| 500–1200 d | 5315 | 158 | 39 873 | 3.96 | 0.47 (.40–.55)*** |

| > 1200 d | 5601 | 148 | 53 809 | 2.75 | 0.31 (.26–.37)*** |

| ACEIc | |||||

| Non-ACEI | 18 029 | 1142 | 147 866 | 7.72 | 1.00 |

| ≤ 50 d | 2535 | 195 | 20 430 | 9.54 | 1.23 (1.05–1.43)** |

| 51–150 d | 5254 | 293 | 42 918 | 6.83 | 0.92 (.81–1.04) |

| 151–550 d | 5091 | 259 | 42 409 | 6.11 | 0.87 (.76–1.00)* |

| > 550 d | 5149 | 190 | 47 880 | 3.97 | 0.50 (.43–.59)*** |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

aRate is incidence rate per 1000 person-years.

bMultivariable analysis including age, sex, urbanization level, monthly income, comorbidities, and medications.

cThe cumulative use days are partitioned in to 4 segments by quartile.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that hypertensive patients taking either ARBs or ACEIs were at a lower risk of viral infections than nonusers. This protective influence of ARBs and ACEIs was observed in the ARB and ACEI cohorts across all ages and in both sexes. Moreover, a dose-response relationship was observed, in that the longer the duration of ARB or ACEI use, the lower the risk of viral infections. This is the first study assessing the association between the risk of viral infections and the use of RAS blockers.

Thus far, no precise basic science data are available that can prove that ACEIs or ARBs could interfere with viral shedding, attachment factors, or co-receptors of viruses [18]. Therefore, the proposed possible mechanism for the lower risk of viral infections among ACEI and ARB users might be that ACEIs and ARBs interfere with the local RAS in the body tissues, thus modulating the body’s immune response to the virus. The RAS regulates blood pressure and fluid and electrolyte balance throughout the body and affects many organs including the heart, kidney, brain, eyes, vascular system, liver, nervous system, reproductive system, and digestive system [19]. Along the RAS axis, angiotensin I (Ang I) and angiotensin II (Ang II) can be converted into Ang (1-7), angiotensin III (Ang III), and angiotensin IV (Ang IV), among which Ang (1-7) was reported to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [20]. Wang et al reported that ACEI or ARB use can inhibit local Ang II levels in the heart and upregulate the expression of ACE2, Ang (1-7), and the Mas receptor axis, thus attenuating myocardial fibrosis after myocardial infarction. Moreover, major transmission routes of viral infections include inhalation of air droplets, direct contact, fecal–oral routes, and blood- and vector-borne disease, which directly affect organs including the lungs, eyes, digestive system, and vasculature, respectively. However, the peripheral RAS is present in all the target organs [21–23]. Therefore, an altered dynamic balance between Ang (1-7), Ang II, Ang III, and Ang IV in these target organs among ACEI or ARB users could cause them to have a lower risk of viral infections compared with nonusers.

Furthermore, although the immunomodulating ability of ACEIs or ARBs has not been clearly elucidated, Cockfield et al discovered that ACEI/ARB users showed decreased interstitial fibrosis/tubule atrophy progression and delayed rejection of renal grafts compared with those using non-RAS blockers [24]. Further studies are needed to clarify the immunomodulating mechanisms of ACEIs and ARBs.

This study has several limitations. First, detailed laboratory information including white cell counts, differential counts, lymphocyte counts, staging of hematological malignancy, and even results of blood smear interpretation are unavailable in the NHIRD. However, we considered variables, which indicate an immunocompromised status including chronic disease, HIV, and transplantation. Second, although we considered many important and common immunosuppressive medications, NHIRD does not contain any information on self-pay target therapy such as rituximab or anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy. Third, NHIRD does not contain personal information on individual hygiene, occupation types that cause exposure to crowds or animals, exercise habits, diet preference, emotional stress, or body mass index. Fourth, this study was conducted on the basis of the ICD-9 registration database. Therefore, if the patients directly took over-the-counter drugs, such as eye drops and cough medications, for their discomforts, these viral infections would be missed. Lack of detailed laboratory data, such as viral culture or polymerase chain reaction of each patient to calculate the type of viral infections for each cohort would also be one inherent limitation of this study. Finally, this study focused on the association between RAS blocker use and risk of viral infections. Therefore, to alleviate surveillance, performance bias, or detection bias, we did not investigate several viral infections such as common viral infections; infections for which children are vaccinated in Taiwan, such as varicella zoster virus or herpes simplex; and viral infections that only occurred in infants such as erythema infectiosum. Finally, because the association between viral infections of the lower respiratory tract (eg, pneumonia) and ACEI use has been widely discussed in previous reports [25–27], lower respiratory tract infections were not considered as an outcome measure to avoid overlap. We also did not consider influenza because annual influenza vaccination rates differed among our study participants, and the flu vaccine is approximately 50%–70% effective [28]; therefore we considered that the above 2 invalid factors would lead to more confounding.

In conclusion, this study revealed that ARB or ACEI users had a lower risk of viral infections than nonusers. Our results should be verified in further studies investigating the underlying mechanisms of these medications. A blinded randomized controlled trial is required, but our data do not suggest a change in clinical practice until more rigorous trial data are available.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. Conception/design: S.-Y. L., C.-H. K. Provision of study materials: C.-H. K. Collection and/or assembly of data: S.-Y. L., C.-L. L., C.-H. K. Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Disclaimer. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding was received for this study.

Financial support. This study is supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (grant number MOHW109-TDU-B-212-114004); China Medical University Hospital (CMU107-ASIA-19, DMR-109–231); MOST Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke (MOST 108-2321-B-039-003-); and the Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.