-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joakim Ölmestig, Ida R Marlet, Rasmus H Hansen, Shazia Rehman, Rikke Steen Krawcyk, Egill Rostrup, Kate L Lambertsen, Christina Kruuse, Tadalafil may improve cerebral perfusion in small-vessel occlusion stroke—a pilot study, Brain Communications, Volume 2, Issue 1, 2020, fcaa020, https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcaa020

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

New treatments for cerebral small-vessel disease are needed to reduce the risk of small-vessel occlusion stroke and vascular cognitive impairment. We investigated an approach targeted to the signalling molecule cyclic guanosine monophosphate, using the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor tadalafil, to explore if it improves cerebral blood flow and endothelial function in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease and stroke. In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot trial (NCT02801032), we included patients who had a previous (>6 months) small-vessel occlusion stroke. They received a single dose of either 20 mg tadalafil or placebo on 2 separate days at least 1 week apart. We measured the following: baseline MRI for lesion load, repeated measurements of blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery by transcranial Doppler, blood oxygen saturation in the cortical microvasculature by near-infrared spectroscopy, peripheral endothelial response by EndoPAT and endothelial-specific blood biomarkers. Twenty patients with cerebral small-vessel disease stroke (3 women, 17 men), mean age 67.1 ± 9.6, were included. The baseline mean values ± standard deviations were as follows: blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery, 57.4 ± 10.8 cm/s; blood oxygen saturation in the cortical microvasculature, 67.0 ± 8.2%; systolic blood pressure, 145.8 ± 19.5 mmHg; and diastolic blood pressure, 81.3 ± 9.1 mmHg. We found that tadalafil significantly increased blood oxygen saturation in the cortical microvasculature at 180 min post-administration with a mean difference of 1.57 ± 3.02%. However, we saw no significant differences in transcranial Doppler measurements over time. Tadalafil had no effects on peripheral endothelial function assessed by EndoPAT and endothelial biomarker results conflicted. Our findings suggest that tadalafil may improve vascular parameters in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease stroke, although the effect size was small. Increased oxygenation of cerebral microvasculature during tadalafil treatment indicated improved perfusion in the cerebral microvasculature, theoretically presenting an attractive new therapeutic target in cerebral small-vessel disease. Future studies of the effect of long-term tadalafil treatment on cerebrovascular reactivity and endothelial function are needed to evaluate general microvascular changes and effects in cerebral small-vessel disease and stroke.

Introduction

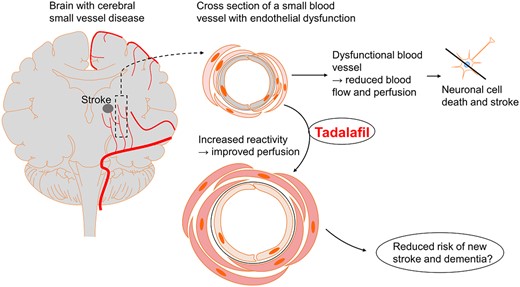

Cellular dysfunction of the endothelial lining of blood vessels may contribute to cerebral small-vessel disease and stroke (Cooke, 2000; Shi and Wardlaw, 2016). Cerebral small-vessel disease is involved in 25% of ischaemic strokes (Sacco et al., 2006). The clinical syndromes of cerebral small-vessel occlusion stroke (lacunar stroke syndrome) (Fisher and Minematsu, 1992) are divided into the following clinical presentations with approximate percentages stated: pure motor stroke (50%), pure sensory stroke (18%), sensorimotor stroke (13%), ataxic hemiparesis (4%), dysarthria–clumsy hand (6%) and atypical lacunar syndrome (9%) (Arboix et al., 2001; Arboix and Marti-Vilalta, 2009). Patients with cerebral small-vessel disease-associated small-vessel occlusion stroke usually have short-term minor symptoms. However, progressive cerebral small-vessel disease and the risk of recurrent stroke can lead to vascular cognitive impairment, severe disability and vascular dementia, even with optimal secondary prevention (Steinke and Ley, 2002; Roh and Lee, 2014). Identifying a treatment that targets cerebrovascular disorder with endothelial dysfunction may have a great impact on mortality and morbidity worldwide.

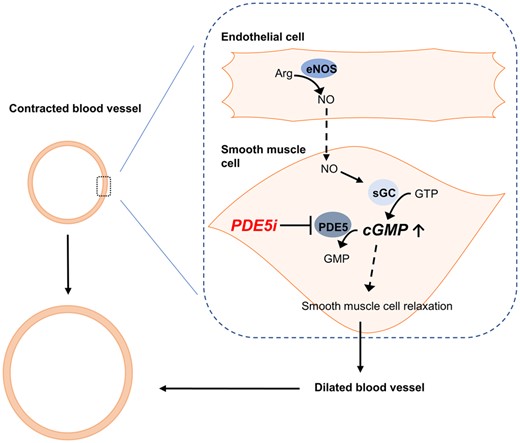

Endothelial dysfunction involves several cellular processes. Reduced production of the signalling molecule nitric oxide (NO) by endothelial NO synthase (Davignon and Ganz, 2004) may be an important mechanism. NO release to the smooth muscle cells mediates relaxation, blood vessel dilation and increased blood flow due to augmentation of the second messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in the smooth muscle cells (Davignon and Ganz, 2004). The enzyme phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is key (Kruuse et al., 2005) for modulating the cGMP response in the smooth muscle cells as it hydrolyses cGMP to inactive guanosine monophosphate (Arnold et al., 1977; Francis et al., 1980; Bender and Beavo, 2006). Blood flow to the brain and most peripheral organs is partly regulated through this mechanism (Cosentino et al., 1993; Kruuse et al., 2001). Dysfunction of the NO–cGMP signalling system may cause impaired cerebral perfusion and cerebrovascular reactivity (Hainsworth et al., 2015). Studies show that patients with cerebral small-vessel disease have reduced cerebral blood flow (CBF) (Markus et al., 2000; O’Sullivan et al., 2002; Schuff et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2016; Arba et al., 2017), potentially explaining why improved blood flow in the deep white and grey matter could be a useful approach to slowing cerebral small-vessel disease pathology and the risk of stroke. Currently, there is no treatment targeting endothelial dysfunction in cerebral small-vessel disease and stroke (Pantoni, 2010; O’Brien and Thomas, 2015).

PDE5 inhibitors (PDE5i) are used to treat erectile dysfunction, benign prostatic hyperplasia and pulmonary hypertension. The most commonly used are sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis) and vardenafil (Levitra). PDE5i reduce cGMP degradation and act as vasodilators by enhancing and prolonging the effect of the NO–cGMP pathway (Maurice et al., 2014) (see Fig. 1 for cellular mechanisms). In addition to dilating peripheral blood vessels, PDE5i reduce platelet aggregation (Gresele et al., 2011). Other PDEi (dipyridamole and cilostazol), not specific to PDE5, have anti-platelet activity and are used as secondary prevention in stroke (Gresele et al., 2011). In general, secondary stroke prevention targets platelets but not the progressive endothelial damage that occurs with cerebral small-vessel disease. In animal studies, PDE5i reduce neuronal apoptosis, oxidative stress and inflammation in the brain after stroke. Furthermore, PDE5i increase angiogenesis and CBF to ischaemic areas of the brain, improve functional outcome and, in some studies, reduce stroke lesion volume (Olmestig et al., 2017).

Proposed model of PDE5i on cerebral blood vessels with endothelial dysfunction. The figure shows a cross-section of a contracted and dilated blood vessel. The dashed box demonstrates the interaction between the endothelial cell and the vascular smooth muscle cell. In endothelial dysfunction, a reduced amount of NO is produced by endothelial cells, leading to reduced cGMP concentration in the vascular smooth muscle cell. PDE5i limit the breakdown of cGMP and, therefore, increase cGMP concentration within the smooth muscle cell and further lead to smooth muscle cell relaxation, dilation of the blood vessel and increased blood flow. The following graphic explanations apply: stimulates (line with arrow  ), inhibits (line with bar

), inhibits (line with bar  ) and stimulates indirectly (dashed line with arrow

) and stimulates indirectly (dashed line with arrow  ). Arg: arginine; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GMP: guanosine monophosphate; GTP: guanosine triphosphate; sGC: soluble guanylyl cyclase.

). Arg: arginine; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GMP: guanosine monophosphate; GTP: guanosine triphosphate; sGC: soluble guanylyl cyclase.

We hypothesized that a single 20-mg dose of tadalafil would temporarily dilate vessels and thus lower blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery (VMCA) and increase blood oxygen saturation in the cortical microvasculature in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease and small-vessel occlusion stroke. We also hypothesized that tadalafil would improve peripheral endothelial function measured by EndoPAT and improve values for endothelial and inflammatory blood markers. Tadalafil was chosen because of its long plasma half-life (17 h) (Forgue et al., 2006) and documented blood–brain barrier penetration in rodents (Garcia-Barroso et al., 2013).

Materials and methods

The trial followed good clinical practice and was monitored by the good clinical practice unit in the Capital Region, Denmark. The Ethics Committee in the capital region of Denmark (H-16020836), the Danish Medicines Agency (EudraCT-number: 2016-000896-26) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (j.nr.: 2012-58-0004) approved this study. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02801032) with the title ‘Effect of Tadalafil on Cerebral Large Arteries in Stroke (ETLAS)’. We obtained informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964, as revised in 2008.

Subjects

We included patients aged 50 years or older, with clinical and radiological evidence of cerebral small-vessel disease and small-vessel occlusion stroke, defined as lacunar stroke, according to the TOAST criteria (Adams et al., 1993). All patients had been admitted to the Department of Neurology, Stroke Unit, Herlev Gentofte Hospital, Denmark, with acute stroke at least 6 months prior to the first trial day. Patients were recruited during hospital admission or through our out-patient clinic. We recruited patients in 2016 and 2017, during which all trial days occurred (see Supplementary material 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Design and experimental protocol

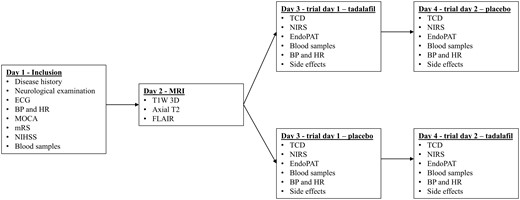

This pilot study was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial (Fig. 2). Trial eligibility was determined using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We performed a neurological examination that included blood pressure measurement (Microlife BP A100, Taipei, Taiwan) and an electrocardiogram (GE Healthcare MAC 5500 HD, Chicago, IL, USA), as well as a basic blood screening with same-day standard analysis. We applied the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale and modified Rankin Scale screening. Prior to the trial, we evaluated the extent of cerebral small-vessel disease and stroke lesions in the brain using cerebral MRI. The MRI scans were evaluated by an experienced neuroradiologist using STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging criteria (Wardlaw et al., 2013). On the trial days, patients were asked to refrain from food and drink starting midnight the day before. Essential medication was allowed.

Study protocol flowchart. BP: blood pressure; ECG: electrocardiogram; FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; HR: heart rate; MOCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; T1W 3D: T1-weighted 3D.

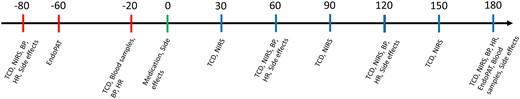

Patients received a single oral dose of either 20 mg tadalafil (Cialis Eli Lilly) or placebo on 2 separate days at least 1 week apart. The Capital Region Hospital Pharmacy, Denmark, performed the blinding and randomization. Medication was blinded by packing tadalafil and the corresponding placebo in opaque unidentifiable capsules. We recorded several measurements at baseline and up to 3 h after medication. These included repeated measurements of mean VMCA by transcranial Doppler (TCD), blood oxygen saturation in the cortical microvasculature (ScO2) on the forehead bilaterally using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), blood pressure and heart rate, peripheral endothelial response by EndoPAT2000 and endothelial and inflammatory biomarkers in peripheral blood samples from a peripheral cubital venous catheter. Figure 3 shows the trial day flowchart. We performed measurements with the patient in supine position on a comfortable bed in a quiet and dimly lit room at 21–24°C. A trial day lasted ∼5 h.

Trial day flowchart. Flowchart over trial day with the described methods. Time shown in minutes with medication time point set to 0 min. Red bars indicate pre-medication methods, green bar indicates medication time point and blue bars indicate post-medication methods. BP: blood pressure; HR: heart rate.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI was performed with a 3-T MRI scanner (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands), applying the following sequences: T1-weighted 3D, axial T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery. MRI scans from the index stroke during hospitalization included T2, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, T2* or susceptibility-weighted imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient sequences.

Transcranial Doppler

A time-averaged VMCA (cm/s) was determined by TCD (2 MHz, Multidop X Doppler, DWL; Lübech & Sipplingen, Germany) with concomitant bilateral measurements taken using handheld probes according to published methods (Kruuse et al., 2002). We calculated the average of four measurements, covering approximately four cardiac cycles, each over a 30-s interval. Furthermore, we calculated a mean VMCA from the right and left VMCA average. To measure VMCA, we chose a fixed point along the middle cerebral artery as close as possible to the bifurcation between the middle cerebral artery and the anterior cerebral artery. This fixed point was used in each individual throughout the study, and each measurement was taken after optimizing the signal from this point. We noted orbitomeatal fix points for reapplication on the second trial day. We took baseline measurements 80 and 20 min before medication administration and took post-medication measurements every 30 min for up to 3 h.

Near-infrared spectroscopy

We measured continuous blood oxygen saturation (%) in the cortical microvasculature (ScO2) using NIRS (INVOS 5100C, Somanetics, Troy, MI, USA) at the wavelengths of 730 and 808 nm and an emitter–detector separation of 3 and 4 cm (Olesen et al., 2018). The two optodes were placed bilaterally on the forehead over each cerebral hemisphere. We placed the centre of each optode on the scalp ∼3 cm above the supraorbital edge to reduce interference from the frontal and sagittal sinuses and supraorbital cutaneous blood vessels (Kishi et al., 2003). Optodes were covered and fixed with tape. Baseline values were defined by a 15-min recording prior to medication administration. Post-medication measurements (5-min duration) were done every 30 min for 3 h, concomitant to TCD measurements. We calculated a mean ScO2 from the right and left ScO2 for each measurement.

EndoPAT

We assessed endothelial function and arterial stiffness by peripheral arterial tonometry, non-invasively using finger plethysmography (EndoPAT2000; Itamar Medical Ltd, Caesarea, Israel) according to the published methods (Hansen et al., 2017; Butt et al., 2018). Peripheral endothelial function was evaluated by measuring the pulse wave amplitude on the index finger via pneumatic finger probes during a reactive hyperaemia phase of the forearm vascular bed (Kuvin et al., 2003). The measurement consisted of a 6-min baseline, 5-min occlusion and 4-min reactive hyperaemia phase. We calculated a reactive hyperaemia index using baseline and reactive hyperaemia pulse wave amplitude values, by a computerized, automated algorithm provided by the EndoPAT2000 software. Reactive hyperaemia index values were automatically normalized to the simultaneous signal from the control arm to reduce potential systemic effects. Arterial stiffness, expressed as an augmentation index, was measured by a computerized, automated analysis of the arterial waveform and averaged from the pulse wave amplitude during the baseline period. The augmentation index was defined as the difference between the second and first systolic peaks in the arterial waveform, expressed as a percentage of the central pulse pressure. Due to the influence of heartrate on augmentation index, the values were automatically normalized to a heart rate of 75 beats per minute (AI@75) by the EndoPAT2000 software. We took EndoPAT recordings at baseline and 3 h post-medication.

Blood sample analysis

A peripheral cubital venous catheter (BD Venflon Pro, NJ, USA) was placed in the dominant arm, and the patient was left resting for 30 min. We drew baseline blood samples immediately prior to administering medication/placebo and sampled again at the end of the trial day. Using multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in commercially available kits (Mesoscale, MD, USA), we analysed the following biomarkers: E-selectin, tumour necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Butt et al., 2018). We diluted samples 2-fold in Diluent 41 prior to measurements and ran enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in duplex. Samples were analysed using the MSD Discovery Workbench software. The concentration for the lower limit of detection was calculated based on a signal 2.5 SD above the blank (zero) calibration value. We accepted a coefficient of variation (CV) value cut-off of 25%.

Blood pressure, heart rate and side effect registration

We measured blood pressure (Microlife BP A100, Taipei, Taiwan), heart rate and side effects twice at baseline and once every hour post-medication for the rest of the trial day. Participants reported side effects on a specific questionnaire for up to 3 days after each trial day. Three days was chosen for side effects reporting because of tadalafil’s long T1/2 (17 h). The questionnaire included prefilled common side effects for tadalafil, as well as blanks to report other experienced side effects.

Statistical analyses

All values in text are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated. This trial was a pilot study, and the outcomes and treatment have never previously been investigated in this patient group. We chose sample size based on previous studies with a similar number of patients who investigated TCD as endpoint in patients with migraine and healthy individuals (Kruuse et al., 2002; Kruuse et al., 2003; Birk et al., 2004; Kruuse et al., 2005). For TCD and NIRS, the mean values for each time point were used for further statistical analyses. All data were corrected by subtracting the mean of pre-medication baseline values. We performed a repeated-measures ANOVA for TCD, NIRS, blood pressure and heart rate. A paired-sample t-test was used to analyse EndoPAT and blood samples. These statistical analyses were used to determine differences between tadalafil and placebo groups before and after treatment. To directly compare the two treatment arms, we calculated delta values by subtracting measurements of corresponding time points from placebo and active treatment. Raw baseline-subtracted data and delta values were analysed using repeated-measures ANOVA. When we found a significant effect of time, we performed further post hoc analyses using paired-sample t-tests. ANOVA was performed using STATA v. 13.1. A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Fully anonymous data used for the findings of this trial are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

Results

Twenty patients were included in this trial. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The patients were distributed according to the relevant lacunar stroke syndrome with 40% with pure motor stroke, 20% with pure sensory stroke, 10% with sensorimotor stroke, 10% with ataxic hemiparesis, 0% with dysarthria–clumsy hand and 20% with atypical lacunar syndrome. One participant dropped out after the first trial day due to side effects (placebo day). This patient was not replaced and not included in further statistical analysis for primary and secondary outcomes. Baseline data for all measurements and index stroke localization are shown in Table 2. We observed no new ischaemic events in any patient from index stroke to inclusion evaluated with MRI post-inclusion. cerebral small-vessel disease extent was assessed using the STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging criteria (Table 3).

| Age (years) | 67.1 ± 9.3 |

| Male gender | 17 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 4.6 |

| Hypertension | 14 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2 |

| Smoking status | |

| Current | 4 |

| Previous | 10 |

| Never | 6 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | |

| Total | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| LDL | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

| HDL | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 37.4 ± 6.4 |

| NIHSS (score range 0–42) | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| mRS (score range 0–6) | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

| MOCA (score range 0–30) | 26.7 ± 2.9 |

| Index stroke localization | |

| Internal capsule/lentiform | 4 |

| Internal border zone | 3 |

| Centrum semiovale | 4 |

| Thalamus/hypothalamus | 6 |

| Brainstem, incl. pons | 4 |

| Anterior border zone | 0 |

| Posterior border zone | 0 |

| Age (years) | 67.1 ± 9.3 |

| Male gender | 17 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 4.6 |

| Hypertension | 14 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2 |

| Smoking status | |

| Current | 4 |

| Previous | 10 |

| Never | 6 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | |

| Total | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| LDL | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

| HDL | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 37.4 ± 6.4 |

| NIHSS (score range 0–42) | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| mRS (score range 0–6) | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

| MOCA (score range 0–30) | 26.7 ± 2.9 |

| Index stroke localization | |

| Internal capsule/lentiform | 4 |

| Internal border zone | 3 |

| Centrum semiovale | 4 |

| Thalamus/hypothalamus | 6 |

| Brainstem, incl. pons | 4 |

| Anterior border zone | 0 |

| Posterior border zone | 0 |

Results shown as mean ± SD or an amount (n). Index stroke localization was determined from an MRI scan (index scan) upon patient admittance to the stroke department.

BMI: body mass index; HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; MOCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

| Age (years) | 67.1 ± 9.3 |

| Male gender | 17 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 4.6 |

| Hypertension | 14 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2 |

| Smoking status | |

| Current | 4 |

| Previous | 10 |

| Never | 6 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | |

| Total | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| LDL | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

| HDL | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 37.4 ± 6.4 |

| NIHSS (score range 0–42) | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| mRS (score range 0–6) | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

| MOCA (score range 0–30) | 26.7 ± 2.9 |

| Index stroke localization | |

| Internal capsule/lentiform | 4 |

| Internal border zone | 3 |

| Centrum semiovale | 4 |

| Thalamus/hypothalamus | 6 |

| Brainstem, incl. pons | 4 |

| Anterior border zone | 0 |

| Posterior border zone | 0 |

| Age (years) | 67.1 ± 9.3 |

| Male gender | 17 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 4.6 |

| Hypertension | 14 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2 |

| Smoking status | |

| Current | 4 |

| Previous | 10 |

| Never | 6 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | |

| Total | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| LDL | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

| HDL | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 37.4 ± 6.4 |

| NIHSS (score range 0–42) | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| mRS (score range 0–6) | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

| MOCA (score range 0–30) | 26.7 ± 2.9 |

| Index stroke localization | |

| Internal capsule/lentiform | 4 |

| Internal border zone | 3 |

| Centrum semiovale | 4 |

| Thalamus/hypothalamus | 6 |

| Brainstem, incl. pons | 4 |

| Anterior border zone | 0 |

| Posterior border zone | 0 |

Results shown as mean ± SD or an amount (n). Index stroke localization was determined from an MRI scan (index scan) upon patient admittance to the stroke department.

BMI: body mass index; HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; MOCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

| TCD (cm/s) | 57.4 ± 10.8 |

| NIRS (ScO2) (%) | 67.0 ± 8.2 |

| DiaBP (mmHg) | 81.3 ± 9.1 |

| SysBP (mmHg) | 145.8 ± 19.5 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 62.4 ± 12.2 |

| EndoPAT | |

| RHI | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| AI | 23.1 ± 16.7 |

| AI@75 | 14.7 ± 14.8 |

| Biomarkers (pg/ml) | |

| E-selectin | 4730 ± 2510 |

| TNF-α | 2.12 ± 0.816 |

| IL-6 | 0.998 ± 0.474 |

| IL-1beta | 0.139 ± 0.104 |

| VCAM-1 | 705 000 ± 27 600 |

| ICAM-1 | 407 000 ± 182 000 |

| VEGF | 22.8 ± 9.01 |

| TCD (cm/s) | 57.4 ± 10.8 |

| NIRS (ScO2) (%) | 67.0 ± 8.2 |

| DiaBP (mmHg) | 81.3 ± 9.1 |

| SysBP (mmHg) | 145.8 ± 19.5 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 62.4 ± 12.2 |

| EndoPAT | |

| RHI | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| AI | 23.1 ± 16.7 |

| AI@75 | 14.7 ± 14.8 |

| Biomarkers (pg/ml) | |

| E-selectin | 4730 ± 2510 |

| TNF-α | 2.12 ± 0.816 |

| IL-6 | 0.998 ± 0.474 |

| IL-1beta | 0.139 ± 0.104 |

| VCAM-1 | 705 000 ± 27 600 |

| ICAM-1 | 407 000 ± 182 000 |

| VEGF | 22.8 ± 9.01 |

Results shown as mean ± SD. Baseline data calculated as a mean of the baseline recording from Visits 1 and 2.

AI: augmentation index; AI@75: augmentation index standardized to a heart rate of 75; DiaBP: diastolic blood pressure; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL: interleukin; RHI: regional hyperaemia index; SysBP: systolic blood pressure; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor alpha; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

| TCD (cm/s) | 57.4 ± 10.8 |

| NIRS (ScO2) (%) | 67.0 ± 8.2 |

| DiaBP (mmHg) | 81.3 ± 9.1 |

| SysBP (mmHg) | 145.8 ± 19.5 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 62.4 ± 12.2 |

| EndoPAT | |

| RHI | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| AI | 23.1 ± 16.7 |

| AI@75 | 14.7 ± 14.8 |

| Biomarkers (pg/ml) | |

| E-selectin | 4730 ± 2510 |

| TNF-α | 2.12 ± 0.816 |

| IL-6 | 0.998 ± 0.474 |

| IL-1beta | 0.139 ± 0.104 |

| VCAM-1 | 705 000 ± 27 600 |

| ICAM-1 | 407 000 ± 182 000 |

| VEGF | 22.8 ± 9.01 |

| TCD (cm/s) | 57.4 ± 10.8 |

| NIRS (ScO2) (%) | 67.0 ± 8.2 |

| DiaBP (mmHg) | 81.3 ± 9.1 |

| SysBP (mmHg) | 145.8 ± 19.5 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 62.4 ± 12.2 |

| EndoPAT | |

| RHI | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| AI | 23.1 ± 16.7 |

| AI@75 | 14.7 ± 14.8 |

| Biomarkers (pg/ml) | |

| E-selectin | 4730 ± 2510 |

| TNF-α | 2.12 ± 0.816 |

| IL-6 | 0.998 ± 0.474 |

| IL-1beta | 0.139 ± 0.104 |

| VCAM-1 | 705 000 ± 27 600 |

| ICAM-1 | 407 000 ± 182 000 |

| VEGF | 22.8 ± 9.01 |

Results shown as mean ± SD. Baseline data calculated as a mean of the baseline recording from Visits 1 and 2.

AI: augmentation index; AI@75: augmentation index standardized to a heart rate of 75; DiaBP: diastolic blood pressure; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL: interleukin; RHI: regional hyperaemia index; SysBP: systolic blood pressure; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor alpha; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

| STRIVE . | Mean ± SD . |

|---|---|

| WMH | |

| Periventricular WMH (0–3) | 2.05 ± 0.83 |

| Deep WMH (0–3) | 1.65 ± 0.93 |

| Microhaemorrhage (n) | 1.45 ± 2.95 |

| Enlarged perivascular space | |

| Basal ganglia (0–4) | 1.25 ± 0.55 |

| Centrum semiovale (0–4) | 1.50 ± 0.76 |

| Midbrain (0–1) | 0.35 ± 0.49 |

| STRIVE . | Mean ± SD . |

|---|---|

| WMH | |

| Periventricular WMH (0–3) | 2.05 ± 0.83 |

| Deep WMH (0–3) | 1.65 ± 0.93 |

| Microhaemorrhage (n) | 1.45 ± 2.95 |

| Enlarged perivascular space | |

| Basal ganglia (0–4) | 1.25 ± 0.55 |

| Centrum semiovale (0–4) | 1.50 ± 0.76 |

| Midbrain (0–1) | 0.35 ± 0.49 |

Evaluated according to ‘STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging’ (STRIVE). White matter hyperintensities are graded according to the Fazekas’s score (Fazekas et al., 1987). Microhaemorrhage presented as mean numbers of microhaemorrhage for all patients included. EPVS for basal ganglia and centrum semiovale is graded from 0 to 4 (Doubal et al., 2010). 0: no EPVS; 1: 1–10 EPVS (mild); 2: 11–20 EPVS (moderate); 3: 21–40 EPVS (frequent); and 4: >40 EPVS (severe). Enlarged perivascular space for midbrain is graded from 0 to 1. 0: no EPVS visible and 1: EPVS visible.

EPVS: enlarged perivascular space; WMH: white matter hyperintensity.

| STRIVE . | Mean ± SD . |

|---|---|

| WMH | |

| Periventricular WMH (0–3) | 2.05 ± 0.83 |

| Deep WMH (0–3) | 1.65 ± 0.93 |

| Microhaemorrhage (n) | 1.45 ± 2.95 |

| Enlarged perivascular space | |

| Basal ganglia (0–4) | 1.25 ± 0.55 |

| Centrum semiovale (0–4) | 1.50 ± 0.76 |

| Midbrain (0–1) | 0.35 ± 0.49 |

| STRIVE . | Mean ± SD . |

|---|---|

| WMH | |

| Periventricular WMH (0–3) | 2.05 ± 0.83 |

| Deep WMH (0–3) | 1.65 ± 0.93 |

| Microhaemorrhage (n) | 1.45 ± 2.95 |

| Enlarged perivascular space | |

| Basal ganglia (0–4) | 1.25 ± 0.55 |

| Centrum semiovale (0–4) | 1.50 ± 0.76 |

| Midbrain (0–1) | 0.35 ± 0.49 |

Evaluated according to ‘STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging’ (STRIVE). White matter hyperintensities are graded according to the Fazekas’s score (Fazekas et al., 1987). Microhaemorrhage presented as mean numbers of microhaemorrhage for all patients included. EPVS for basal ganglia and centrum semiovale is graded from 0 to 4 (Doubal et al., 2010). 0: no EPVS; 1: 1–10 EPVS (mild); 2: 11–20 EPVS (moderate); 3: 21–40 EPVS (frequent); and 4: >40 EPVS (severe). Enlarged perivascular space for midbrain is graded from 0 to 1. 0: no EPVS visible and 1: EPVS visible.

EPVS: enlarged perivascular space; WMH: white matter hyperintensity.

Transcranial Doppler

Repeated measurement analyses showed no significant difference in ΔVMCA between tadalafil and placebo from baseline to 3 h post-medication (P = 0.37). However, when we compared the two treatments using a paired-sample t-test for all time points, we observed significant differences. Thirty minutes post-medication, ΔVMCA was significantly lower in the tadalafil group than in the placebo group with a mean difference of 2.39 ± 4.01 cm/s (P = 0.009). After 90 min, the mean difference between groups was 2.54 ± 4.60 cm/s (P = 0.013). We found no significant difference in ΔVMCA at the remaining time points.

Near-infrared spectroscopy

We observed a significant difference from baseline to 3 h post-medication in ScO2 levels between the treatments (P = 0.0014), and post hoc analyses showed an increase in ScO2 in the tadalafil group with a mean difference of 1.57 ± 3.02% at 180 min post-medication (P = 0.018). We found no significant difference in ScO2 at earlier time points (see Fig. 4).

Result graphs. Results shown as mean ± SD. Delta values between measurements at a specific time point compared with the baseline value. Blue data series represents the tadalafil group, and red represents the placebo group. Graph A shows transcranial Doppler, graph B shows near-infrared spectroscopy, graph C shows diastolic blood pressure and graph D shows systolic blood pressure. For visual purposes, the baseline recordings are set to time −80 and 0 min for the TCD graph, −80 and 0 min for the blood pressure graphs and 0 min for the NIRS graph. A reduced cerebral blood flow is well known in cerebral small-vessel disease. In this pilot trial, we found that tadalafil may increase cerebral microperfusion in small-vessel occlusion stroke. This is interesting, since it suggests a new target in treating this cerebrovascular disease. A larger clinical trial is planned.

EndoPAT

We found no significant differences in peripheral endothelial function between tadalafil and placebo groups when comparing all measurements from baseline to 180 min post-medication: reactive hyperaemia index (P = 0.45), augmentation index (P = 0.19) and AI@75 (P = 0.19).

Blood pressure and heart rate

Diastolic blood pressure significantly decreased over time in the tadalafil group compared to the placebo group (P = 0.0011). Tadalafil treatment reduced the diastolic blood pressure relative to the placebo group at 60, 120 and 180 min post-medication. The mean difference after 60 min was 5.26 ± 8.40 mmHg (P = 0.007), the mean difference after 120 min was 4.74 ± 9.85 mmHg (P = 0.025) and the mean difference after 180 min was 7.89 ± 7.34 mmHg (P = 0.0001). There was no significant difference in systolic blood pressure (P = 0.125) or heart rate (P = 0.718) over time.

Endothelial and inflammatory biomarkers

Levels of IL-1β were significantly lower in the tadalafil group than in the placebo group at 180 min post-medication, with a mean difference between groups of 0.0870 ± 0.139 pg/ml (P = 0.014). Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 levels were significantly higher in the tadalafil group, with a mean difference between groups of 217 ± 209 ng/ml (P = 0.0089). Likewise, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 levels were significantly higher in the tadalafil group, with a mean difference between groups of 125 ± 329 ng/ml (P = 0.021). We found no significant differences between tadalafil and placebo groups for levels of E-selectin (P = 0.39), tumour necrosis factor alpha (P = 0.31), IL-6 (P = 0.42) or VEGF (P = 0.47).

Side effects

We noted few side effects from medication and placebo treatment. After the trial days, 28 out of 39 side effect handouts were returned. All registered side effects were self-limited within 1 day (see Table 4 for registered side effects).

| Side effects . | Tadalafil . | Placebo . |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | 2 | 1 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 1 |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 |

| Nasal congestion | 1 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 |

| Sleeping problem | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 |

| Side effects . | Tadalafil . | Placebo . |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | 2 | 1 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 1 |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 |

| Nasal congestion | 1 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 |

| Sleeping problem | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 |

The side effects shown in the table were registered. Results shown as the number of subjects who experienced side effects after tadalafil and placebo administration.

| Side effects . | Tadalafil . | Placebo . |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | 2 | 1 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 1 |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 |

| Nasal congestion | 1 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 |

| Sleeping problem | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 |

| Side effects . | Tadalafil . | Placebo . |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | 2 | 1 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 1 |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 |

| Nasal congestion | 1 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 |

| Sleeping problem | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 |

The side effects shown in the table were registered. Results shown as the number of subjects who experienced side effects after tadalafil and placebo administration.

Discussion

In this randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study, we investigated whether tadalafil treatment had vascular effects in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease and previous small-vessel occlusion stroke. The patients also had additional signs of cerebral small-vessel disease, including higher Fazekas scores, enlarged perivascular space and microbleeds, as determined by the STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging criteria (Table 3). Previous studies of patients with migraine and healthy young subjects showed that PDE5i, such as sildenafil, do not change VMCA (Kruuse et al., 2002; Kruuse et al., 2003). However, we hypothesized different findings in patients with altered endothelial function. Here, we found that tadalafil treatment significantly increased blood oxygen saturation in the cortical microvasculature as measured by NIRS 180 min after administration of tadalafil compared to placebo. Using repeated-measures ANOVAs, we found no difference in TCD results between treatments over time. However, when using a paired-sample t-test to compare individual time points for tadalafil and placebo treatments, we noted a significant decrease in VMCA in the tadalafil group. Thus, our TCD results warrant further studies because these results are ambiguous. In addition, effects of tadalafil treatment on the size of various cerebral vessels should be tested in larger trials. We saw that the tadalafil group had significantly lower diastolic blood pressure than the placebo group. There was no effect on peripheral endothelial function measured with EndoPAT. Interestingly, the tadalafil group had lower levels of circulating inflammatory marker IL-1β and higher levels of the adhesion molecules vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 compared to the placebo group. These findings indicate endothelial involvement, but further studies are needed to fully understand these implications.

Stroke is not based on just one disease pathology but encompasses a range of cerebro- or cardiovascular changes and causes. Anti-platelet therapy is used for most subgroups of ischaemic stroke, but it does not target the underlying vascular pathology of most patients with cerebral small-vessel disease. Some patients with small-vessel occlusion stroke secondary to occlusion or stenosis at the origin of a deep penetrating artery by a microatheroma or a plaque (branch atheromatous disease) have a high risk of recurrent stroke. These patients may reduce the risk of recurrent stroke if treated with anti-platelet therapy due to the atheromatous component (Arboix et al., 2014).

Endothelial dysfunction with reduced NO–cGMP signalling in the vessel wall is a likely component in mediating cerebral small-vessel disease and small-vessel occlusion stroke (Horsburgh et al., 2018), as well as a contributor to reduced CBF in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease (Shi et al., 2016). Therefore, cGMP degradation inhibitors, specifically the PDE5i, could increase either local or general CBF in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease, thus presenting a potential new treatment target for cerebral small-vessel disease. This mechanism is of particular interest because PDE5 expression does not appear to diminish with age (Vasita et al., 2019), unlike endothelial NO synthase (Seals et al., 2011). Studies evaluating CBF or surrogate markers of CBF in healthy subjects found no change in CBF or VMCA after PDE5i treatment (Kruuse et al., 2002; Arnavaz et al., 2003; Kruuse et al., 2009). However, NO–cGMP signalling should be intact in healthy subjects. It is proposed that PDE5i treatment only increases CBF in cases of a dysfunctional NO–cGMP signalling (Diomedi et al., 2005; Rosengarten et al., 2006; Al-Amran et al., 2012), as seen in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease and endothelial dysfunction (Knottnerus et al., 2009; Hainsworth et al., 2015). Our findings after a single dose of tadalafil support this theory.

NIRS makes it possible to measure blood oxygen saturation in the microvasculature of the cerebral cortex, which can serve as a surrogate for regional cerebral tissue perfusion and regional CBF (Reinhard et al., 2006; Oldag et al., 2016). An increase in ScO2 signal is considered to correlate to an increase in CBF and perfusion (Vernieri et al., 2004; Taussky et al., 2012). In this study, TCD sonography was used to assess vascular conditions by measuring blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral arteries (D’Andrea et al., 2016). Combining NIRS and TCD makes it possible to assess cerebrovascular reactivity and CBF, though studies using the two methods simultaneously are scarce (D’Andrea et al., 2016; Oldag et al., 2016).

We found that a single dose of tadalafil significantly increased ScO2 at 180 min post-medication compared to placebo. Starting at 60 min post-medication, we observed a non-significant increase in ScO2 (see Fig. 4). These results suggest that tadalafil improved superficial regional cerebral tissue perfusion and regional CBF by affecting cerebral microvasculature. These findings are consistent with previous results of studies of elderly subjects where sildenafil improved muscle perfusion in peripheral small arteries (Nyberg et al., 2015). In the TCD data, we detected a non-significant trend towards a lower VMCA in the tadalafil group compared to placebo. Dilation of cerebral blood vessels may lead to a decrease in VMCA if the flow is kept constant according to the principles of F = πr2 × V (flow = blood vessel cross-section area × blood flow velocity) (Dahl et al., 1989). Thus, our results could indicate minor vasodilatory response to tadalafil. Since the results are non-significant, we cannot conclude on this based on our data. In previous studies on healthy subjects, the PDE5i sildenafil did not alter CBF or dilate normal appearing large cerebral arteries (Kruuse et al., 2002). The trend in velocity change detected in the present study may reflect an altered NO–cGMP pathway related to endothelial dysfunction.

Another interesting, but novel view on cerebral small-vessel disease concerns capillary dysfunction. Neuronal tissue with capillary dysfunction has reduced CBF and perfusion. To accompany a reduced blood supply, an increase in blood oxygen extraction is seen (Ostergaard et al., 2016), which theoretically could correspond to a reduced ScO2. We found an increase in ScO2 after tadalafil, which should be seen in cerebral tissue with increased perfusion. The issue of capillary dysfunction in cerebral small-vessel disease requires further investigation.

Few studies have assessed the effect of PDE5i in human cerebral stroke (Lorberboym et al., 2010; Lorberboym et al., 2014; Di Cesare et al., 2016). Two studies of sildenafil or tadalafil use measured CBF using single-photon emission computed tomography before and after treatment (Lorberboym et al., 2010; Lorberboym et al., 2014). Both PDE5i reduced regional CBF in areas peripheral to the prior stroke; however, other areas mostly contralateral to the stroke showed increased regional CBF, indicating a steal phenomenon that shunted blood from the affected area (Lorberboym et al., 2010; Lorberboym et al., 2014). However, these general stroke studies were not specific for patients with cerebral small-vessel disease. The effects of a PDE5i (PF-03049423) on functional outcome in patients with acute stroke were the focus of a single study. The authors found no effect using several tests, including the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale, modified Rankin Scale and different neuropsychological tests; however, the study indicated a good tolerability profile (Di Cesare et al., 2016). Moreover, another study tested the tolerability of 25 mg sildenafil in subacute stroke and revealed a good safety profile in this patient group (Silver et al., 2009).

We found no significant change in peripheral endothelial function as measured by EndoPAT2000. However, we previously found that same-day measurements were moderately reliable in healthy individuals and patients with stroke, which limits the use of these results (Hansen et al., 2017). As expected, tadalafil significantly reduced diastolic blood pressure compared to placebo, a well-documented effect (Kruuse et al., 2002; Prisant, 2006).

Tissue inflammation may be involved in cerebral small-vessel disease pathophysiology because activation of inflammatory cytokines and recruitment of inflammatory cells are believed to induce neuronal cell damage (Yilmaz and Granger, 2008; Rouhl et al., 2012; Wiseman et al., 2014). Activation of these inflammatory pathways is thought to be associated with blood–brain barrier dysfunction, but more evidence is needed (Shi and Wardlaw, 2016). Our study showed that tadalafil caused a significant decrease in IL-1β, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, known to worsen cell damage post-stroke (Dinarello, 2010; Lopez-Castejon and Brough, 2011). Levels of tumour necrosis factor alpha and IL-6 were not affected by tadalafil treatment, though these inflammatory markers are more active in the acute inflammatory response post-stroke and probably not the chronic inflammation seen in cerebral small-vessel disease (Waje-Andreassen et al., 2005; Bokhari et al., 2014). VEGF, a neuroprotective growth factor involved in neurovascular remodelling post-stroke (Ma et al., 2012), was not affected by tadalafil treatment. Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and E-selectin are involved in inflammatory cells adhesion to the endothelium and transport across the blood–brain barrier to the ischaemic area (Yilmaz and Granger, 2008). We observed that tadalafil had no significant effect on E-selectin levels but increased plasma levels of both vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. This increase was unexpected based on our hypothesis that tadalafil would decrease the inflammatory response, based on previous findings where sildenafil treatment lowered these markers in patients with type 2 diabetes (Aversa et al., 2008). The extent and role of these inflammatory and endothelial markers role in cerebral small-vessel disease remains unclear.

This trial indicates that PDE5i have positive effects on cerebrovascular reactivity and cerebral blood perfusion in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease stroke. Our results generate hypotheses for future larger studies. A parallel clinical trial was conducted in a similar population group as our study, which applied a single dose of tadalafil and used arterial spin labelling MRI (clinical trial number: NCT02450253) (Pauls et al., 2017). This study aimed to detect regional CBF changes in deep brain areas, but results are not yet published.

The possible role of brain atrophy in cerebral small-vessel disease and cognitive impairment is highly interesting. It is well known that patients with cerebral small-vessel disease have more abundant brain atrophy compared to age-matched controls; however, the mechanisms involved remain to be found (Wardlaw et al., 2013). One study found that only patients with cerebral small-vessel disease with brain atrophy showed signs of cognitive impairment (Grau-Olivares et al., 2010). Another study on patients with cerebral small-vessel disease with recurrent stroke found that brain atrophy was caused by the small-vessel occlusion strokes (Duering et al., 2012). These findings suggest that cognitive impairment in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease is related to brain atrophy following small-vessel occlusion stroke. The role of non-symptomatic covert small-vessel occlusion stroke on cognition may be an important target to investigate, since it has been found that these patients have increased the risk of neuropsychological deficits and cognitive impairment (Blanco-Rojas et al., 2013).

We propose that additional studies should investigate long-term effects of daily tadalafil administration in combination with CBF measurements. Further studies on patients with cerebral small-vessel disease should also include evaluations of brain atrophy and extended neuropsychological evaluations to understand this disease better.

Limitations

The study was designed as a pilot to detect if tadalafil improved vascular parameters in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease with previous stroke. The small number of patients in this pilot study limits the possibility of detecting significant differences between the measured variables but indicates trends for further investigation. Although we aimed to recruit both sexes, few women participated in the study, resulting in a selection bias. In addition, TCD measurements meant that only large vessels were detected and NIRS measurements were only localized to the frontal lobes. Future studies should apply methods to assess global CBF and regional or deep brain area blood flow, such as arterial spin labelling MRI or PET. When doing TCD, we did not assess end-tidal PCO2, which is a variable known to influence VMCA (Cencetti et al., 1997). However, previous studies found that PCO2 did not change after sildenafil treatment (Kruuse et al., 2003). Finally, NIRS measurements might be influenced by extracranial vasculature or venous sinuses and results could be biased by optode replacement between trial days (Kishi et al., 2003). We addressed this concern by measuring and noting the position of the optodes.

Conclusion

This pilot study found that a single dose of tadalafil (20 mg) improved some vascular measurements in patients with radiological and clinical evidence of cerebral small-vessel disease stroke. Tadalafil increased regional blood oxygen saturation in the microvasculature of the brain 180 min post-medication, indicating improved perfusion of the cerebral microvasculature. Tadalafil treatment also decreased diastolic blood pressure. These effects were minor but significant. Future studies need to further investigate the effects of PDE5i on CBF and perfusion in patients with cerebral small-vessel disease stroke, ideally using MRI or PET techniques.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Ulla Damgaard Munk for her assistance with blood sample analysis.

Funding

This study was financed from a scholarship from the University of Copenhagen. Medical expenses were funded by AP Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Sciences and the Foundation for Neurological Research. C.K. was funded by Borregaard Stipend, Novo Nordic Foundation, Grant number NNF18OC0031840.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

References

Abbreviations

- CBF =

cerebral blood flow

- cGMP =

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- IL =

interleukin

- NIRS =

near-infrared spectroscopy

- NO =

nitric oxide

- PDE5 =

phosphodiesterase 5

- PDE5i =

PDE5 inhibitors

- TCD =

transcranial Doppler

- VMCA =

velocity in the middle cerebral artery