-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marcus Deschauer, Holger Hengel, Katrin Rupprich, Martina Kreiß, Beate Schlotter-Weigel, Mona Grimmel, Jakob Admard, Ilka Schneider, Bader Alhaddad, Anastasia Gazou, Marc Sturm, Matthias Vorgerd, Ghassan Balousha, Osama Balousha, Mohammed Falna, Jan S Kirschke, Cornelia Kornblum, Berit Jordan, Torsten Kraya, Tim M Strom, Joachim Weis, Ludger Schöls, Ulrike Schara, Stephan Zierz, Olaf Riess, Thomas Meitinger, Tobias B Haack, Bi-allelic truncating mutations in VWA1 cause neuromyopathy, Brain, Volume 144, Issue 2, February 2021, Pages 574–583, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa418

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The von Willebrand Factor A domain containing 1 protein, encoded by VWA1, is an extracellular matrix protein expressed in muscle and peripheral nerve. It interacts with collagen VI and perlecan, two proteins that are affected in hereditary neuromuscular disorders. Lack of VWA1 is known to compromise peripheral nerves in a Vwa1 knock-out mouse model. Exome sequencing led us to identify bi-allelic loss of function variants in VWA1 as the molecular cause underlying a so far genetically undefined neuromuscular disorder. We detected six different truncating variants in 15 affected individuals from six families of German, Arabic, and Roma descent. Disease manifested in childhood or adulthood with proximal and distal muscle weakness predominantly of the lower limbs. Myopathological and neurophysiological findings were indicative of combined neurogenic and myopathic pathology. Early childhood foot deformity was frequent, but no sensory signs were observed. Our findings establish VWA1 as a new disease gene confidently implicated in this autosomal recessive neuromyopathic condition presenting with child-/adult-onset muscle weakness as a key clinical feature.

See Arribat (doi.10.1093/brain/awaa464) for a scientific commentary on this article.

Introduction

Neuromuscular disorders are characterized by progressive muscle weakness arising from damage to anterior horn cells, peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junction or muscle itself. The majority of pathologies have a genetic aetiology with more than 150 loci being associated with muscle disorders and approximately 100 loci with neurogenic weakness (Benarroch et al., 2020). Some gene defects can result in myopathic and neurogenic weakness in the same patient. These disorders were named neuromyopathy (Milone and Liewluck, 2019).

The implementation of next generation sequencing-based genetic testing such as gene panel or whole exome sequencing has proven a powerful tool to address the diagnostic challenge associated with the extreme genetic heterogeneity and phenotypic variability of neuromuscular disorders (Kuhn et al., 2016; Krenn et al., 2020). However, it is estimated that at least half of the affected individuals and their families remain without a definitive molecular diagnosis partly due to technical limitations, e.g. targeted short-read sequencing approaches or incomplete annotation of detected variants. This diagnostic gap is commonly believed to be addressed in the nearby future by full genome datasets augmented with long-read sequences and/or RNA sequencing (Cummings et al., 2017). Another major challenge in rare disease diagnosis as well as research is that although the putatively disease-causal defect might be readily detected, it might take years to establish statistical evidence supporting the association of a given variant or potential disease gene with a specific phenotype.

Here, we report results of an exome sequencing study in six families comprising 15 individuals clinically diagnosed with a neuromuscular disorder without a molecular diagnosis. Bi-allelic truncating variants in VWA1 (encoding for the von Willebrand Factor A domain containing 1 protein) were detected. This protein is a component of basement membranes particularly in muscle and peripheral/central nervous system. Thus, a novel candidate gene for a neuromyopathy was identified.

Material and methods

Patients and exome sequencing

Exome sequencing was performed at two centres in Munich (Families F1 and F2) and Tübingen (Families F3, F4, F5, and F6) on genomic DNA from affected Patients F1-II.2, F2-II.1, F3-II.3, F3-II.4, F4-II.2, F5-II.2, and F6-II.1, as previously described (Haack et al., 2012; Fritzen et al., 2018). Families F1 and F2 were initially investigated in the context of a follow-up research study on a clinically preselected cohort of 10 individuals remaining without a diagnosis after diagnostic panel analysis of myopathy-associated disease genes (Kuhn et al., 2016). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals or their guardians. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the Technical University of Munich. Genetic findings are summarized in Table 1.

| ID . | Sex . | Ethnicity . | cDNA (NM_022834.4) . | Protein (NP_073745.2) . | Consanguinity of parents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | Roma | c.252del homozygous | p.(Glu85Serfs*58) | First cousins | |

| F1-II.2 | Male | ||||

| F1-II.4 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.6 | Male | ||||

| Family 2 | German | c.62_71dup c.94C>T compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg32*) | No | |

| F2-II.1 | Male | ||||

| Family 3 | Arab | c.62_71del homozygous | p.(Gly21Alafs*12) | First cousins | |

| F3-II.3 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.4 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.7 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.9 | Female | ||||

| Family 4 | German | c.62_71dup c.879del compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg293Serfs *58) | No | |

| F4-II.1 | Female | ||||

| F4-II.2 | Female | ||||

| Family 5 | German | c.186_209del homozygous | p.(Pro63_Ala 70del) | No | |

| F5-II.1 | Male | ||||

| F5-II.2 | Male | ||||

| Family 6 | German | c.62_71dup homozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) | No | |

| F6-II.1 | Male |

| ID . | Sex . | Ethnicity . | cDNA (NM_022834.4) . | Protein (NP_073745.2) . | Consanguinity of parents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | Roma | c.252del homozygous | p.(Glu85Serfs*58) | First cousins | |

| F1-II.2 | Male | ||||

| F1-II.4 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.6 | Male | ||||

| Family 2 | German | c.62_71dup c.94C>T compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg32*) | No | |

| F2-II.1 | Male | ||||

| Family 3 | Arab | c.62_71del homozygous | p.(Gly21Alafs*12) | First cousins | |

| F3-II.3 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.4 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.7 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.9 | Female | ||||

| Family 4 | German | c.62_71dup c.879del compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg293Serfs *58) | No | |

| F4-II.1 | Female | ||||

| F4-II.2 | Female | ||||

| Family 5 | German | c.186_209del homozygous | p.(Pro63_Ala 70del) | No | |

| F5-II.1 | Male | ||||

| F5-II.2 | Male | ||||

| Family 6 | German | c.62_71dup homozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) | No | |

| F6-II.1 | Male |

| ID . | Sex . | Ethnicity . | cDNA (NM_022834.4) . | Protein (NP_073745.2) . | Consanguinity of parents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | Roma | c.252del homozygous | p.(Glu85Serfs*58) | First cousins | |

| F1-II.2 | Male | ||||

| F1-II.4 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.6 | Male | ||||

| Family 2 | German | c.62_71dup c.94C>T compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg32*) | No | |

| F2-II.1 | Male | ||||

| Family 3 | Arab | c.62_71del homozygous | p.(Gly21Alafs*12) | First cousins | |

| F3-II.3 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.4 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.7 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.9 | Female | ||||

| Family 4 | German | c.62_71dup c.879del compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg293Serfs *58) | No | |

| F4-II.1 | Female | ||||

| F4-II.2 | Female | ||||

| Family 5 | German | c.186_209del homozygous | p.(Pro63_Ala 70del) | No | |

| F5-II.1 | Male | ||||

| F5-II.2 | Male | ||||

| Family 6 | German | c.62_71dup homozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) | No | |

| F6-II.1 | Male |

| ID . | Sex . | Ethnicity . | cDNA (NM_022834.4) . | Protein (NP_073745.2) . | Consanguinity of parents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | Roma | c.252del homozygous | p.(Glu85Serfs*58) | First cousins | |

| F1-II.2 | Male | ||||

| F1-II.4 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F1-II.6 | Male | ||||

| Family 2 | German | c.62_71dup c.94C>T compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg32*) | No | |

| F2-II.1 | Male | ||||

| Family 3 | Arab | c.62_71del homozygous | p.(Gly21Alafs*12) | First cousins | |

| F3-II.3 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.4 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.5 | Female | ||||

| F3-II.7 | Male | ||||

| F3-II.9 | Female | ||||

| Family 4 | German | c.62_71dup c.879del compound heterozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) p.(Arg293Serfs *58) | No | |

| F4-II.1 | Female | ||||

| F4-II.2 | Female | ||||

| Family 5 | German | c.186_209del homozygous | p.(Pro63_Ala 70del) | No | |

| F5-II.1 | Male | ||||

| F5-II.2 | Male | ||||

| Family 6 | German | c.62_71dup homozygous | p.(Gly25Argfs*74) | No | |

| F6-II.1 | Male |

RNA sequencing

Fibroblasts for RNA extraction were available from two patients (Patients F1-II.2 and F5.II.1). RNA was isolated using QIAGEN RNeasy® Mini Kit. RNA quality was assessed with the Agilent 2100 Fragment Analyzer total RNA kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). All samples had high RNA integrity numbers (RIN >9). Using the NEBNext® Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep kit with 100 ng of total RNA input for each sequencing library, poly(A)-selected sequencing libraries were generated according to the manufacturer’s manual. All libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform as 2 × 100 bp paired-end reads and to a depth of ∼50 million clusters each. Quality of raw RNA-seq data in FASTQ files was assessed using ReadQC (version 2020_03) to identify potential sequencing cycles with low average quality and base distribution bias. Reads were preprocessed with SeqPurge (version 2020_03) and aligned using STAR (version 2.7.3a) allowing spliced read alignment to the human reference genome (build GRCh37). Alignment quality was analysed using MappingQC (ngs-bits version 2020_03) and visually inspected with Broad Integrative Genome Viewer (version 2.8.2). Based on the Ensembl genome annotation (GRCh37, Ensembl release 97), read counts for all genes were obtained using subread (version 2.0.0). For comparative gene expression analysis, we used in-house transcriptome datasets from 50 fibroblast cell lines derived from individuals with unrelated phenotypes as controls. Raw gene counts were normalized by weighted trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) normalization and modelled with a generalized linear model following the method implemented in edgeR (version 3.26.8) (Robinson et al., 2010; McCarthy et al., 2012). Z-scores were calculated based on log2-transformed normalized expression values.

Clinical examinations

Muscle MRI scans of seven patients were performed in different centres with different protocols but grading of fatty infiltration and oedema of all scans was performed by a single radiologist (J.S.K.). For grading of fatty infiltration a modified Mercuri scale was used (1: no fatty atrophy to 4: >60% fatty atrophy; Schlaeger et al., 2018). For grading of oedema the Morrow scale was used (1: no oedema to 4: severe intramuscular oedema; Morrow et al., 2013). Brain MRIs performed at different centres were available from three patients. Muscle biopsies were available from three patients. Cryosectioning and staining were performed according to standard protocols. Evaluation was performed by two co-authors who are experts in histological examination of muscle biopsies (M.V. and I.S.). Transmission electron microscopy of glutaraldehyde-fixed, resin-embedded muscle tissue of one individual was performed as described previously (Goswami et al., 2015). EMG was performed in seven patients and nerve conduction studies in 10 patients in different centres using standard methods.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request. Human variants and phenotypes have been deposited in the ClinVar database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar) under the submission reference SUB6915912.

Results

Exome analysis

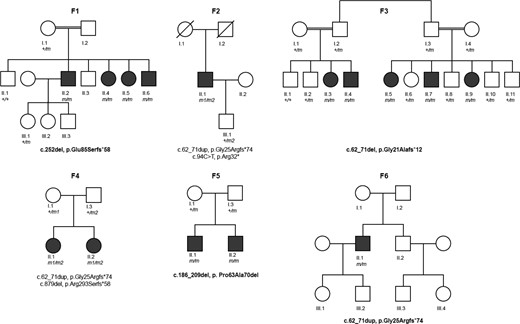

In Patient F1-II.2, based on the reported consanguinity of the parents and autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, we prioritized homozygous non-synonymous variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.1% in the Genome Aggregation Database [gnomAD (11/2019)] and our in-house databases containing ∼19 700 exomes. The homozygous deletion c.252del [p.Glu85Serfs58*] (GeneBank: NM_022834.4) in VWA1 (MIM: 611901) was considered a good candidate because of its predicted truncating nature and expression in peripheral nerve and muscle tissue. Moreover, the same filtering strategy lead us to the identification of compound heterozygous truncating variants (c.62_71dup; c.94C>T, [p.Gly25Argfs*74]; [p.Arg32*]) in another similarly affected individual (Patient F2-II.1). A subsequent search for bi-allelic VWA1 variants in a cohort of individuals with neuromuscular disorders unsolved after exome sequencing based on scientific collaboration (Family F3) or diagnostic routine exome sequencing (Families F4–F6) identified different pathogenic variants in an additional 10 affected individuals from four families. No additional candidate variants in genes known to be associated with neurological or muscular disorders (either recessive or dominant) were identified in the exome datasets of investigated individuals. Sanger sequencing showed full segregation in all available healthy and affected family members and that variants were bi-allelic (Fig. 1).

Pedigrees of investigated families. Pedigrees of six families with bi-allelic variants in VWA1 in affected individuals. Filled black symbols = affected individuals; crossed symbols = deceased individual. Variants in VWA1 are presented below pedigrees. Homozygous variants are presented in bold (m in the pedigrees). Compound heterozygous mutations are presented in two rows (first row, m1 in the pedigrees and second row, m2 in the pedigrees).

All six identified variants are either absent or very rare (MAF < 0.001) in gnomAD (Supplementary Table 1). None of the variants have been reported in a homozygous state in gnomAD or our in-house databases containing >19 700 exome datasets of individuals with unrelated phenotypes. Furthermore, no homozygous loss-of-function VWA1 variants were observed in gnomAD (v.2.1.1 and v.3).

Five of the six identified variants are predicted loss of function variants due to a premature termination of protein translation. One variant c.186_209del [p.Pro63Ala70del] is an in-frame deletion resulting in a deletion of eight amino acids within the VWA1 domain. One of these amino acids, the glycine at position 67, is highly conserved across different species including Xenopus tropica and Danio rerio (Fig. 2).

![Variants in VWA1. Structure of VWA1 (top) and VWA1 (bottom) with protein domains and motifs (predicted by PFAM; El-Gebali et al., 2019) of the gene product and position of the identified variants. Conservation of the amino acids across different species that are deleted due to the c.186_209del [p.Pro63Ala70del] variant.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/brain/144/2/10.1093_brain_awaa418/2/m_awaa418f2.jpeg?Expires=1749766804&Signature=rhls~6ZlVEySb7MoKx5qaRDtquzQC0OrFLkUmCyq5dGQgZ4U0V~h-7lpoD0BRI4JvGwj4odGLKKLhS~BNiquWQ32xUETGVsrgPkUttmb8y2S1A1rfcu2A~ZFiaWNtleeL7FJKNNLQtDPHbFyUDb7CaD~WNYDklpEbQxTda-PmJ83RnyuxjIazwuW4IAfPhR3iinMonYWpHICYFSt0TQWfnQRGveTr1-qH9Xio2H-3M1iA~6VHGBsE1GoX~VVH9HghuRWq6juva-ff16-fIOmuqaRAuR2ikBdABACxDGn6ZeBvDJzL0vVvX0pv9SiSCEeswhsVqmtytAOuIwEg959Vw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Variants in VWA1. Structure of VWA1 (top) and VWA1 (bottom) with protein domains and motifs (predicted by PFAM; El-Gebali et al., 2019) of the gene product and position of the identified variants. Conservation of the amino acids across different species that are deleted due to the c.186_209del [p.Pro63Ala70del] variant.

A 10-bp tandem repeat is located in exon 1 of VWA1. This repeat is duplicated in one variant (c.62_71dup [p.Gly25Argfs*74]) and deleted in another variant (c.62_71del [p.Gly21Alafs*12]). Interestingly, the duplication was detected in three independent German families, either in homozygous state (Family F6) or in compound heterozygosity with other loss of function variants (Families F2 and F4), which initially raised the possibility of a founder mutation. However, analysis of the respective exomes did not reveal shared rare variants in direct proximity to the duplication. Among the identified VWA1 variants the duplication is the most frequent variant in gnomAD v.3.0 (11/2019) with a MAF of 0.06%. Both, the duplication and the deletion are present in different populations (European, Latino, African, South Asian, Ashkenazi Jewish). We therefore hypothesize that this tandem repeat is prone to de novo alterations and that the variants have occurred independently of one another.

The parents of the affected individuals of Families 1 and 3 were reportedly consanguineous resulting in homozygous state of the VWA1 variant in the affected family members. In Family 5 the homozygous VWA1 variant c.186_209del, which was not present in gnomAD, is located within a 5.6 Mb run of homozygosity indicative for a distant relatedness of the parents.

RNA sequencing

Analysis of VWA1 mRNA in RNA-seq data from Patient F5-II.1 showed the presence of the in-frame deletion c.186_209del in the transcript. No significant changes (z = 0.8) were observed in overall VWA1 transcript expression levels compared to controls. In contrast, the position of the frameshift variant c.252del was not covered in the RNA-seq data of Patient F1-II.2 due to significantly reduced (z = −1.7) expression level of the VWA1 transcript. This observation is in line with a partial nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (Supplementary Fig. 1). Differential expression analyses did not reveal transcriptome-wide significant changes pointing towards pathway-specific alterations or changes in the expression levels of postulated interaction partners of the VWA1 protein.

Clinical characteristics

Neurological examination

Fifteen affected individuals from six independent families of German, Arabic, and Roma origin were identified. Phenotypic details are summarized in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2. Clinical onset varied substantially ranging from age 2 years to 54 years with weakness in the lower limbs affecting proximal and distal muscles as first symptom. There was prominent weakness of foot extension with difficulties of standing on heels in all patients. In addition, three individuals showed proximal arm muscle weakness. Muscle atrophy was prominent in lower legs in four individuals only (illustrated in Patient F5-II.2 in Fig. 3). Congenital or early childhood foot deformities were reported in 11 of 15 cases (illustrated in six individuals in Fig. 3). Three individuals received operative extensions of the Achilles tendon (illustrated in Patients F4-II.2 and F3-II.7 in Fig. 3). Sensory symptoms or signs were absent. No clinical signs of CNS involvement were observed.

| ID . | Age of weakness onset, years . | Current age, years . | First symptoma . | Muscle weaknessb . | Foot deformities . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper legs . | Lower legs . | Arms . | . | |||||||

| Ant. . | Post. . | Ant. . | Post. . | Prox. . | Dist. . | |||||

| Family 1 | ||||||||||

| F1-II.2 | 43 | 64 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 2–3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | No |

| F1-II.4 | 54 | 60 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.5 | 46 | 53 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.6 | 41 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | No |

| Family 2 | ||||||||||

| F2-II.1 | 13 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 0/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 3 | ||||||||||

| F3-II.3 | 3 | 11 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.4 | 6 | 9 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.5 | 3 | 34 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.7 | 2 | 30 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.9 | 18 | 25 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral pes cavus | |||||

| Family 4 | ||||||||||

| F4-II.1 | 2 | 17 | Delayed start of walking | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus |

| F4-II.2 | 3 | 13 | Gait difficulty | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes equinus |

| Family 5 | ||||||||||

| F5-II.1 | School age | 45 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F5-II.2 | School age | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1–2/5 | 2–3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 6 | ||||||||||

| F6-II.1 | 40 | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5R, 5/5L | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes cavus |

| ID . | Age of weakness onset, years . | Current age, years . | First symptoma . | Muscle weaknessb . | Foot deformities . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper legs . | Lower legs . | Arms . | . | |||||||

| Ant. . | Post. . | Ant. . | Post. . | Prox. . | Dist. . | |||||

| Family 1 | ||||||||||

| F1-II.2 | 43 | 64 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 2–3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | No |

| F1-II.4 | 54 | 60 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.5 | 46 | 53 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.6 | 41 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | No |

| Family 2 | ||||||||||

| F2-II.1 | 13 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 0/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 3 | ||||||||||

| F3-II.3 | 3 | 11 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.4 | 6 | 9 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.5 | 3 | 34 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.7 | 2 | 30 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.9 | 18 | 25 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral pes cavus | |||||

| Family 4 | ||||||||||

| F4-II.1 | 2 | 17 | Delayed start of walking | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus |

| F4-II.2 | 3 | 13 | Gait difficulty | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes equinus |

| Family 5 | ||||||||||

| F5-II.1 | School age | 45 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F5-II.2 | School age | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1–2/5 | 2–3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 6 | ||||||||||

| F6-II.1 | 40 | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5R, 5/5L | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes cavus |

Additional phenotypic features and results of instrumental examinations are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Ant. = anterior; Dist. = distal; ND = not done; Post. = posterior; Prox. = proximal.

Apart from foot deformities.

Medical research council (MRC) scale.

| ID . | Age of weakness onset, years . | Current age, years . | First symptoma . | Muscle weaknessb . | Foot deformities . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper legs . | Lower legs . | Arms . | . | |||||||

| Ant. . | Post. . | Ant. . | Post. . | Prox. . | Dist. . | |||||

| Family 1 | ||||||||||

| F1-II.2 | 43 | 64 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 2–3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | No |

| F1-II.4 | 54 | 60 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.5 | 46 | 53 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.6 | 41 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | No |

| Family 2 | ||||||||||

| F2-II.1 | 13 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 0/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 3 | ||||||||||

| F3-II.3 | 3 | 11 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.4 | 6 | 9 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.5 | 3 | 34 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.7 | 2 | 30 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.9 | 18 | 25 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral pes cavus | |||||

| Family 4 | ||||||||||

| F4-II.1 | 2 | 17 | Delayed start of walking | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus |

| F4-II.2 | 3 | 13 | Gait difficulty | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes equinus |

| Family 5 | ||||||||||

| F5-II.1 | School age | 45 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F5-II.2 | School age | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1–2/5 | 2–3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 6 | ||||||||||

| F6-II.1 | 40 | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5R, 5/5L | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes cavus |

| ID . | Age of weakness onset, years . | Current age, years . | First symptoma . | Muscle weaknessb . | Foot deformities . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper legs . | Lower legs . | Arms . | . | |||||||

| Ant. . | Post. . | Ant. . | Post. . | Prox. . | Dist. . | |||||

| Family 1 | ||||||||||

| F1-II.2 | 43 | 64 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 2–3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | No |

| F1-II.4 | 54 | 60 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.5 | 46 | 53 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | No |

| F1-II.6 | 41 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | No |

| Family 2 | ||||||||||

| F2-II.1 | 13 | 46 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 0/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 3 | ||||||||||

| F3-II.3 | 3 | 11 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.4 | 6 | 9 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F3-II.5 | 3 | 34 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.7 | 2 | 30 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus | |||||

| F3-II.9 | 18 | 25 | Leg weakness | ND | Bilateral pes cavus | |||||

| Family 4 | ||||||||||

| F4-II.1 | 2 | 17 | Delayed start of walking | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes equinovarus |

| F4-II.2 | 3 | 13 | Gait difficulty | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes equinus |

| Family 5 | ||||||||||

| F5-II.1 | School age | 45 | Leg weakness | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| F5-II.2 | School age | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1–2/5 | 2–3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral pes cavus |

| Family 6 | ||||||||||

| F6-II.1 | 40 | 44 | Leg weakness | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5R, 5/5L | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | Bilateral congenital pes cavus |

Additional phenotypic features and results of instrumental examinations are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Ant. = anterior; Dist. = distal; ND = not done; Post. = posterior; Prox. = proximal.

Apart from foot deformities.

Medical research council (MRC) scale.

Phenotypic findings illustrated by photos of patients. Images of affected individuals showing foot deformities with pes cavus in Patients F2-II.1, F4-II.2, F5-II.1 and F6-II.1, pes equinovarus in Patient F3-II.5, surgically corrected pes equinovarus in Patient F3-II.7 and Achilles tendon lengthening in Patients F4-II.2 and F3-II.7. Lower leg atrophy can be clearly seen in Patient F5-II.2.

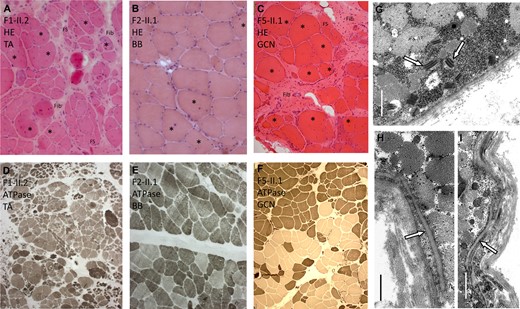

Histological examination of muscle biopsies

Muscle biopsies of three individuals (Patients F1-II.2, F2-II.1, and F5-II.1) revealed myopathic changes (increased fibre size variation and increase of internalized nuclei) in tibialis anterior, biceps brachii and gastrocnemius muscle, respectively (illustrated in haematoxylin and eosin staining in Fig. 4A–C). In the biopsy of Patients F1-II.2 and F5.II.1, neurogenic changes were also observed (ATPase staining Fig. 4D and F). A report of an additional biopsy of the quadriceps muscle of Patient F2-II.1 also revealed a mixture of myopathic and neurogenic changes. Electron microscopy of the muscle biopsy of Patient F1-II.2 revealed groups of mitochondria with paracrystalline osmiophilic inclusions in several muscle fibres (Fig. 4G). There were no disruptions of the continuity of muscle fibre basal laminae or other overt alterations of the endomysial extracellular matrix (Fig. 4I). However, several muscle fibres showed invaginations of the sarcolemma that were not associated with myotendinous junctions (Fig. 4I).

Muscle biopsy findings. (A–C) Haematoxylin and eosin stainingand (D–F) ATPase stainingof muscle biopsies in Patients F1-II.2, F2.II.1 and F5-II.1 are shown. (G–I) Electron microscopy of the muscle biopsy in Patient F1-II.2 is demonstrated. (A) Patient F1-II.2: tibialis anterior muscle (TA) showing severely increased fibre size variation, increase of internalized nuclei (asterisk), regenerative changes with whorled fibres (WF), fibre splitting (FS) and increased endomysial and perimysial fibrosis (Fib). (B) Patient F2-II.1: biceps brachii muscle (BB) showing mild increase of fibre size variation and of internalized nuclei (asterisk). (C) Patient F5-II.1: Gastrocnemius muscle (GCN) showing severely increased fibre size variation, increase of internalized nuclei (asterisk) and increased endomysial and perimysial fibrosis (Fib). (D) Patient F1-II.2: ATPase staining demonstrating grouping of atrophic fibres and fibre types indicating neurogenic changes. (E) Patient F2-II.1: ATPase staining demonstrating only mild fibre type grouping. (F) Patient F5-II.1: ATPase staining demonstrating fibre type grouping. (G) Electron microscopy shows osmiophilic paracrystalline inclusions (arrows) in several muscle fibre mitochondria (Scale bar = 1.5 µm). (H) No apparent focal disruptions of muscle fibre basal lamina (arrow) integrity was observed (Scale bar = 0.8 µm), but (I) invaginations of the sarcolemma (arrow) are seen (Scale bar = 1.5 µm).

Neurophysiological examination

EMG revealed abnormal motor unit action potentials in six of seven patients showing a mixed myopathic and neurogenic pattern. Myopathic changes were prominent in proximal muscles whereas chronic neurogenic changes were dominant in distal muscles. Fibrillations were present in six of seven patients. Nerve conduction studies revealed diminished motor amplitudes at the legs in 6 of 10 patients with normal or mildly reduced velocities (Supplementary Table 2). Sensory potentials of sural nerves were normal in four of seven patients. In two patients, amplitudes were mildly reduced and in Patient F2-II.1 who suffered from insulin-dependent diabetes for many years no stimulus response was observed (Supplementary Table 2).

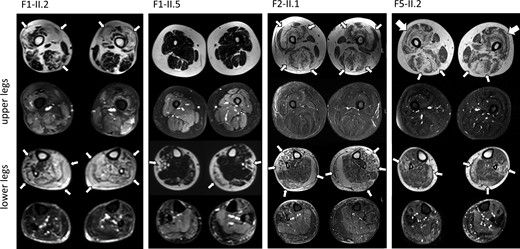

Magnetic resonance examination

Fatty degeneration in upper and lower legs was observed in all seven investigated individuals. Intriguingly, muscle MRI of lower limbs showed a rather uniform pattern with predominant affection of the vastus (medialis/lateralis/intermedius) and the gastrocnemius (medial more than lateral head) as well as the peroneal muscles. In more advanced stages, also the tibialis anterior, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris muscles were severely affected. All patients showed a relative sparing of the gracilis, sartorius, and soleus muscles (Supplementary Table 2). In Patient F5-II.2 a sandwich sign in the vastus laterals muscles was observed (Fig. 5). Brain MRI was performed in three individuals (Patients F2-II.1, F4-II.2 and F6-II.1) and was normal.

Muscle MRI findings. MRI of the legs demonstrates fatty degeneration (thin arrows) of muscle in Patients F1-II.2, F1-II.5, F2-II.1, and F5-II.2. There is predominant affection of the vastus and the medial head of the gastrocnemius as well as the peroneal muscles. A ‘sandwich sign’ (thick arrows) in the vastus lateralis muscles was present in Patient F5-II.2.

Discussion

We have identified truncating bi-allelic variants in VWA1 in six families with a so far genetically unidentified neuromuscular disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance. All variants are very rare in control data bases and they segregated with the disease in our families.

VWA1 is located on chromosome 1p36.33 and codes for the 445 amino acids of the VWA1 protein (also known as WARP) which is a member of the von Willebrand factor A domain (VWFA) protein superfamily containing a VWA-domain followed by two fibronectin III repeats (Fitzgerald et al., 2002) (Fig. 1B). Human VWA1 (NP_073745.2) and mouse (NP_680085.3) protein are 75.3% identical. A reporter gene knock-in mouse model showed that VWA1 is a component of basement membranes in several tissues including muscle and vasculature of CNS and endoneurium of peripheral nerves. Interaction of VWA1 with collagen VI and perlecan was identified leading to the hypothesis that VWA1 functions in establishing or maintaining the blood–brain barrier and blood–neural barrier (Allen et al., 2008). Pathogenic variants in collagen genes (COL6A1, COL6A2, COL6A3, and COL12A1) (Mohassel et al., 2018) and in the perlecan gene HSPG2 (Nicole et al., 2000) cause well-known neuromuscular disorders such as congenital myopathies type Bethlem/Ullrich and Schwarz-Jampel syndrome, indicating this pathway as highly relevant for neuromuscular diseases. Electron microscopy of muscle performed in one of our patients showed paracrystalline inclusions in the mitochondria, a finding that can also be observed in collagen VI-related myopathies (Mohassel et al., 2018). However, no changes of muscle fibre basal laminae were observed. A sandwich sign that is typically observed in collagen VI myopathies in muscle MRI (Mohassel et al., 2018) was present in one of our patients only. Our first RNA-seq-based studies performed on patient-derived fibroblast cell lines established from two patients did not indicate a significant alteration of the proteins that a relevant in the basement membranes. However, these preliminary results are of limited significance because of the small sample size (n = 2) and the fact that fibroblast cell lines might not represent a suitable model system for a disease phenotype predominantly affecting neuronal and/or muscle cells.

In another mouse model with VWA1-null mutation motor function and behavioural testing showed significantly delayed response to acute painful stimulus and impaired fine motor coordination suggesting compromised peripheral nerve function. Immunostaining of VWA1-interacting ligands showed that collagen VI microfibrillar matrix was severely reduced and mislocalized in peripheral nerves. Ultrastructural analysis revealed reduced fibrillar collagen deposition within the peripheral nerve extracellular matrix and abnormal partial fusing of adjacent Schwann-cell basement membranes. However, there were no abnormalities reported in muscle (Allen et al., 2009).

The phenotype of the affected individuals reported in this study was characterized by muscle weakness affecting primary foot extension in nearly all individuals, a finding compatible with motor neuropathy. Foot deformities were frequently present, a typical sign in hereditary neuromuscular disorders. Some patients showed pes cavus typically observed in hereditary neuropathies. Other patients showed pes equinovarus that can be observed in certain neuropathies (e.g. TRPV4 and GDAP1 related) and myopathies (e.g. GMPPB and LMNA related), sometimes with congenital onset overlapping with distal arthrogryposis (Senderek et al., 2003; Quijano-Roy et al., 2008; Evangelista et al., 2015; Astrea et al., 2018). Additionally, proximal muscle weakness was observed in most individuals being a typical myopathic sign. EMG showed mixed myopathic and neurogenic changes. Reduced amplitudes in motor nerve conduction studies correlated with neurogenic changes in EMG indicating axonal neuropathy or motor neuron affection. Muscle biopsies of affected individuals demonstrated myopathic changes and also neurogenic changes in two individuals. Together, our observations argue that the muscular phenotype associated with loss of VWA1 function likely arises from neurogenic as well as myopathic damage and can be accordingly designated as neuromyopathy.

Several other examples for neurogenic and myopathic changes being present in the same affected individual have been reported rendering hereditary neuromyopathies an increasingly recognized disease entity. Mutations in the bicaudal Drosophila homologue 2 [BICD2 (MIM: 609797)] were first described in autosomal dominant spinal muscular atrophy with predominant lower limb weakness and hereditary spastic paraplegia (MIM: 61529). In some individuals myopathic changes were observed in EMG in addition to myohistologically confirmed neurogenic and myopathic changes (Unger et al., 2016; Bugiardini et al., 2019). Mutations in the genes coding small heat-shock 27-kD protein 1 and 8 [HSPB1 (MIM: 602195) and HSPB8 (MIM: 608014)] were initially identified in individuals with autosomal dominant distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN). Subsequently individuals with HSPB1 and HSPB8 mutations were found to have a coexisting neuropathy and distal myopathy (Ghaoui et al., 2016; Lewis-Smith et al., 2016; Bugiardini et al., 2017; Cortese et al., 2018). Furthermore, a pathogenic variant in mitofusin 2 [MFN2 (MIM: 608507)] was identified in an individual with neuromyopathy (Bugiardini et al., 2019). There is the remaining possibility that secondary myopathic changes are observed in a neurogenic process, and vice versa EMG can appear neurogenic in a chronic end-stage myopathy. However, in the affected individuals reported in this manuscript coexisting myopathic and neurogenic changes were observed early in the disease course. Our findings support the notion that separation of clinical entities into either nerve or muscle damage may not be appropriate in certain neuromuscular disorders.

There is striking variability of age of onset of the affected individuals not only between the families but also within family F3. Onset in childhood was present in Families F2–F5 whereas adult-onset was observed in Families F1 and F6. In hereditary neuromuscular disorders variable age of onset not explained by the gene defect is sometimes observed. For example, in patients with late-onset Pompe disease bearing similar acid α-glucosidase genotypes onset can range from <1 year to 52 years (Kroos et al., 2007). In our families we did not identify additional variants that are likely to act as disease modifiers in other genes such as collagen VI genes that are known to interact with VWA1.

In conclusion, we provide compelling evidence that bi-allelic truncating VWA1 variants are the disease-causing molecular defect of a neuromuscular disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance. Findings of muscle biopsies and needle EMG revealed neurogenic and myopathic changes indicating a neuromyopathy. Genetic testing of VWA1 should be included in the diagnostic work-up of individuals presenting with progressive muscle weakness primarily affecting proximal and distal muscles of the legs, and also in neuromuscular disorders with foot deformities.

Web resources

The URLs for the data presented herein are: gnomAD server, https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), https://omim.org/

Acknowledgements

We thank all the families for their participation. We thank Dr Sarah Bublitz for support with the clinical examination, Prof. Gisela Stoltenburg-Didinger for help with myopathological investigations, and Dr Leila Scholle for providing fibroblasts of one patient. We thank Melanie Kraft, Claudia Bauer, Karin Hamann and Beate Kootz for excellent technical assistance. We thank Mrs E. Beck and Dr I. Katona for support with electron microscopy.

Funding

H.H. was supported by the intramural fortüne program (#2554-0-0). T.B.H. was supported by the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) through the Juniorverbund in der Systemmedizin “mitOmics” (FKZ 01ZX1405C to T.B.H.), the intramural fortüne program (#2435-0-0) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation – Projektnummer 418081722). C.K., H.H., and L.S. are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases (ERN-RND), project ID 739510.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

References

Author notes

Marcus Deschauer and Holger Hengel contributed equally to this work.