-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Maia Osborne-Grinter, Sian Cousins, Jozel Ramirez, James R Price, Luca Lancerotto, Matthew Gardiner, Ronelle Mouton, Robert Hinchliffe, Guidance for delivering surgical procedures outside operating theatres: scoping review, BJS Open, Volume 8, Issue 6, December 2024, zrae104, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrae104

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This review aimed to examine in-depth the extent and content of guidance related to the delivery of surgical procedures outside of the operating theatre.

Documents concerning the delivery of surgical procedures in non-operating theatre settings were eligible for inclusion. Guidance documents were identified from three sources: electronic databases (MEDLINE and Embase), professional organization websites and expert knowledge. No time limits were imposed. Endoscopic, interventional radiology/cardiology, dental and obstetric procedures were excluded. Eligible documents were included if specifications on the setting and descriptions of procedures were provided. Study titles, abstracts and full texts were screened for relevance. A standardized data extraction form was developed, focusing on: document type, surgical specialty, rationale for developing the guidance, setting specifications, staffing requirements, patient information and safety; descriptive statistics summarized data where appropriate. Verbatim text extracted was summarized descriptively.

Of 375 documents identified, 173 full manuscripts were reviewed and 17 were included in the scoping review, published between 1992 and 2022. Guidance provided by documents was limited. They typically included information about general procedures, setting specifications and equipment that may be required to deliver appropriate procedures in the non-operating theatre setting. There was significant heterogeneity in the terminology used to describe the non-operating theatre setting. Appropriate procedures were commonly minor procedures performed under local or topical anaesthesia. The non-theatre setting was recommended to be of adequate size for all appropriate equipment and personnel, with considerations for lighting, waste disposal, ventilation and emergency equipment. Documents also described appropriate training for staff and requirements for personal protective equipment, surgical record keeping, and occupational health and safety guidelines.

This scoping review has demonstrated there is significant heterogeneity in guidance documents concerning the delivery of surgical procedures in the non-theatre setting. Standardization of terminology and definitions is required to help inform stakeholders about the development of non-theatre setting practices.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed unprecedented pressure on the National Health Service (NHS)1. The need to prioritize urgent COVID-19-related care has resulted in a backlog across non-COVID-19 services, and the number of patients waiting for hospital treatment in England reached a record level of over 7 million in December 20222. Closure and reallocation of operating theatres to treat patients with COVID-19 and the redeployment of surgical staff meant elective surgical procedures across specialties have been delayed or cancelled during the pandemic3–7. It is unclear how long this backlog will take to clear but estimates suggest that it may remain for years, rather than months8–10. The ongoing and worsening NHS workforce shortages impact further on service delivery11. This can mean a worsening of symptoms, deterioration of conditions6 and increased healthcare costs4 as patients continue to face long waiting lists.

There is a need to provide strategies to meet this rise in demand and clear the backlog safely1. In the UK, innovations in response to increased waiting lists across specialties have been developed, including cancer hubs, and the utilization of extra capacity in the independent sector. The acute drop in operating capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic has led to innovation in the way surgeons deliver their service, with some surgical procedures traditionally delivered in operating theatres being delivered in procedure and outpatient clinic settings. Although the delivery of ‘out-of-theatre’ surgery during COVID-19 has been seen predominantly for trauma procedures (due to the cancellation of elective procedures), this is not a new concept. Invasive procedures such as treatment of varicose veins in vascular surgery and fistula creation for renal replacement therapy have been historically delivered outside of the operating theatre. More recently, in the field of hand surgery, there is a rising trend internationally for some moderate complexity procedures traditionally delivered in operating theatres, such as carpal tunnel decompression, to be delivered in procedure and clinic room settings12.

However, the movement to out-of-theatre surgery has not been seen more widely in the NHS, and most surgical procedures in all specialties are delivered in standard operating theatres, with over 1.72 million procedures performed in standard operating theatres in 201713. This has been highlighted by NHS Improvement as an opportunity for reducing waiting lists by freeing up operating theatres for more complex cases13. In addition, operating theatres generate approximately 50–70% of total hospital waste14,15 and a non-operating theatre setting allows patients to be treated efficiently with smaller surgical teams, a reduced carbon footprint and less waste16. The NHS defines an operating theatre as ‘a room in a hospital site… containing one or two operating tables (…) the facilities needed for the bulk of the work available for all patients shall permit: positioning of the patient(s) on the table(s) or the device(s) so as to render the operative treatment possible or convenient, adjustable illumination of sufficient power to permit fine or delicate work, the operative treatment to take place in aseptic conditions which shall include the provision of sterile instruments and facilities for all staff to change clothing and the provision of pain relief during the operative treatment more elaborate than basal sedation administered on the ward, self-administered inhalation or infiltration with local anaesthetic’17. NHS Estates recommend that the standard operating theatre should be a minimum of 55 m2, should have an anaesthetic room of 19 m2 minimum, a dedicated scrub area, prep room and postoperative recovery room, have standardized equipment and positive pressure ventilation of an appropriate standard18.

The movement of appropriate procedures from these resource-intensive environments to procedure or clinic rooms may be an attractive option to patients, surgeons, healthcare management teams and commissioners, given the reduced time, space, personnel and equipment required16. However, there are potential issues, including, but not limited to, safety and potential increased rates of infection, re-organization costs and the availability of equipment necessary to perform the procedure. Prospective studies have found low incidences of postoperative wound infection following carpal tunnel decompressions performed outside of the operating theatre in Canada, where over 70% of these procedures are performed in this setting12. Major invasive procedures utilizing general anaesthesia will still require delivery in operating theatres, however, less invasive, more minor procedures that require local or no anaesthesia may be suitable for delivery out of the operating theatre.

Currently, there is a lack of guidance in this area, and so the existence, extent and content of any guidance is hitherto unknown. Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to examine in-depth the extent and content of guidance related to the delivery of surgical procedures outside of the operating theatre.

Methods

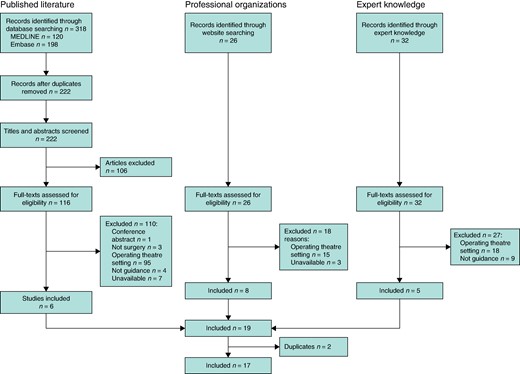

All results from this work are presented using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines19 and checklist and the review was registered prospectively on the international prospective register of systematic reviews, PROSPERO (CRD42021274998).

Eligibility criteria

Guidance documents related to the delivery of surgical procedures in non-operating theatre settings were eligible for inclusion. This is defined as any documents including any advice or recommendations for the delivery of surgery outside of the operating theatre, outlining steps for the movement of surgery to outside the operating theatre, standards describing the required quality or characteristics of out-of-theatre settings and/or surgical procedures, and formal policies.

Surgical procedures were defined as any procedure where access to the body is gained via an incision delivered within any surgical specialty. If documents referred only to endoscopic, interventional radiology/cardiology, dental or obstetric procedures they were excluded as these are routinely delivered in specialist, non-operating theatre settings. Guidance related to the delivery of surgical co-interventions such as anaesthesia was also included.

Non-operating theatre settings include any setting where procedures take place that are not operating theatres17, including procedure, treatment, clinic or outpatient rooms, with multipurpose or dedicated functions, with no or natural ventilation. Primary care surgeries were included within this remit for the purposes of this review. Documents providing guidance for ‘ambulatory’, ‘day’, ‘office-based’ or ‘clinic-based’ surgery were only included if these specified the surgical setting to be outside of a formal operating theatre in a procedure or clinic room. Where definitions were not provided or used unclear terminology, they were excluded due to probable lack of relevance. This is because the use of these terms is not standardized and may include the delivery of surgery in operating theatres within and outside of inpatient hospital settings.

Eligible documents included details related to: specifications of non-operating theatre settings where procedures may be performed (for example procedure/outpatient rooms), including guidance for health facilities planning and management or requirements for accreditation of facilities delivering procedures in non-operating theatre settings; and descriptions of procedures that may be delivered in non-operating theatre settings, including guidance related to the delivery of specific procedures in non-operating theatre settings (for example carpal tunnel decompression).

Eligible document types included published literature (including original articles, commentaries, reviews, opinion pieces, editorials, responses, reviews) and publicly available documents/web pages produced by the government, royal colleges and professional organizations. Conference abstracts were excluded due to probable lack of sufficient detail. Non-English language documents were also excluded.

Identifying documents and searches

Documents were identified from three main sources.

Electronic databases

To ensure contemporary relevance of articles, articles published since 2010 were identified by systematic searches in MEDLINE (Ovid SP) and Embase electronic databases. Search strategies tailored to each database combined keywords and subject headings related to three concepts: surgical procedures, non-operating theatre setting and guidance/guidelines (Supplementary materials, Table S1). Retrieved articles were exported into an Endnote database and deduplicated.

Screening was conducted by at least two independent authors. Titles and abstracts were screened, and ineligible articles excluded. Full texts of the remaining articles were retrieved and screened against eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Reverse and forward snowball searches identified potentially relevant documents cited by included documents.

Professional organization websites

Relevant professional organizations and royal colleges worldwide were identified by expert knowledge and preliminary web searches (Supplementary materials, Table S2). Professional organizations were likely to include those related to surgery and anaesthesia, healthcare delivery and oversight, and healthcare facilities design, management and accreditation. Guidance included was that related to surgical specialties likely to perform minor procedures that may be suitable for delivery outside of the operating theatre (for example hand surgery). Websites of identified organizations were searched by one member of the research team and any potentially eligible documents were screened by a second author. Where search functions allowed, key words such as ‘procedure’/‘outpatient’ rooms, ‘surgery’, ‘procedures’, ‘guidelines’ were used. No time limits were imposed.

Expert knowledge

Eligible articles identified by expert knowledge were included. Experts were senior researchers and consultants in their field. All potentially eligible documents identified were screened by two authors. No time limits were imposed.

Outcomes of interest and analysis

A standardized data extraction form was developed. Areas for data extraction were initially identified by the team, and the form was then piloted to ensure that no potentially relevant information was missed; the form was then iterated between the team and finalized. The following data was extracted into the Redcap (11.0.3; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) data capture software: document type (for example published paper, website, country of origin), specialty and surgical procedure (for example anaesthetics, plastic surgery), rationale for developing the guidance, procedures specified as being suitable for delivery in a non-operating theatre setting, including any named procedures, terms used to describe groups of procedures (for example minor) and definitions and procedure characteristics, non-operating theatre setting specifications and equipment, staffing requirements, including necessary training, patient information provision and consent, and patient safety specifications. Data extraction was done by one reviewer, with data extracted from 20% of included articles by a second reviewer to identify any potential systematic discrepancies to ensure accuracy and standardization. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Descriptive statistics summarized data where appropriate. Verbatim text extracted was summarized descriptively.

Results

Searches retrieved 375 documents. After deduplication, 279 were screened and 17 included in the final synthesis (Fig. 1).

Document type

Sixteen documents were dedicated guidance documents, and one paper was a commentary, including guidance (Table 1). All but three papers were produced by a professional organization. Publication dates ranged between 1992 and 2022. Seven papers each were published in the UK and USA and one each in South Africa, Ireland and Australia (Table 1).

| First author . | Country . | Source . | Professional organization . | Specialty . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Yates et al.21 | USA | Published literature | American Society of Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgical Facilities | None |

| Sterling et al.22 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Dermatology |

| Grobler et al.23 | Africa | Expert knowledge | N/A | Anaesthetics |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence24 | UK | Professional bodies | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | None |

| Humphreys et al.25 | UK | Expert knowledge | Healthcare Infection Society | Multiple |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Australia | Professional bodies | Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) | Anaesthetics |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | UK | Professional bodies | British Association of Day Surgery | Multiple |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand28 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | USA | Expert knowledge | American Society of Anesthesiologists | Anaesthetics |

| Van Demark et al.30 | USA | Published literature | American Association for Hand Surgery | Plastic surgery |

| Zimmerman et al.31 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Urology |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | UK | Professional bodies | Royal College of Anaesthetists | Anaesthetics |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand33 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | UK | Expert knowledge | British Society for Surgery of the Hand; British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons | Plastic surgery |

| National Clinical Programme in Surgery34 | Ireland | Professional bodies | National Clinical Programme in Surgery | None |

| First author . | Country . | Source . | Professional organization . | Specialty . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Yates et al.21 | USA | Published literature | American Society of Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgical Facilities | None |

| Sterling et al.22 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Dermatology |

| Grobler et al.23 | Africa | Expert knowledge | N/A | Anaesthetics |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence24 | UK | Professional bodies | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | None |

| Humphreys et al.25 | UK | Expert knowledge | Healthcare Infection Society | Multiple |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Australia | Professional bodies | Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) | Anaesthetics |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | UK | Professional bodies | British Association of Day Surgery | Multiple |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand28 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | USA | Expert knowledge | American Society of Anesthesiologists | Anaesthetics |

| Van Demark et al.30 | USA | Published literature | American Association for Hand Surgery | Plastic surgery |

| Zimmerman et al.31 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Urology |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | UK | Professional bodies | Royal College of Anaesthetists | Anaesthetics |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand33 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | UK | Expert knowledge | British Society for Surgery of the Hand; British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons | Plastic surgery |

| National Clinical Programme in Surgery34 | Ireland | Professional bodies | National Clinical Programme in Surgery | None |

N/A, not applicable.

| First author . | Country . | Source . | Professional organization . | Specialty . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Yates et al.21 | USA | Published literature | American Society of Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgical Facilities | None |

| Sterling et al.22 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Dermatology |

| Grobler et al.23 | Africa | Expert knowledge | N/A | Anaesthetics |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence24 | UK | Professional bodies | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | None |

| Humphreys et al.25 | UK | Expert knowledge | Healthcare Infection Society | Multiple |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Australia | Professional bodies | Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) | Anaesthetics |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | UK | Professional bodies | British Association of Day Surgery | Multiple |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand28 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | USA | Expert knowledge | American Society of Anesthesiologists | Anaesthetics |

| Van Demark et al.30 | USA | Published literature | American Association for Hand Surgery | Plastic surgery |

| Zimmerman et al.31 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Urology |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | UK | Professional bodies | Royal College of Anaesthetists | Anaesthetics |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand33 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | UK | Expert knowledge | British Society for Surgery of the Hand; British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons | Plastic surgery |

| National Clinical Programme in Surgery34 | Ireland | Professional bodies | National Clinical Programme in Surgery | None |

| First author . | Country . | Source . | Professional organization . | Specialty . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Drake et al.20 | USA | Published literature | American Academy of Dermatology | Dermatology |

| Yates et al.21 | USA | Published literature | American Society of Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgical Facilities | None |

| Sterling et al.22 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Dermatology |

| Grobler et al.23 | Africa | Expert knowledge | N/A | Anaesthetics |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence24 | UK | Professional bodies | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | None |

| Humphreys et al.25 | UK | Expert knowledge | Healthcare Infection Society | Multiple |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Australia | Professional bodies | Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) | Anaesthetics |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | UK | Professional bodies | British Association of Day Surgery | Multiple |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand28 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | USA | Expert knowledge | American Society of Anesthesiologists | Anaesthetics |

| Van Demark et al.30 | USA | Published literature | American Association for Hand Surgery | Plastic surgery |

| Zimmerman et al.31 | USA | Published literature | N/A | Urology |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | UK | Professional bodies | Royal College of Anaesthetists | Anaesthetics |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand33 | UK | Professional bodies | British Society for Surgery of the Hand | Plastic surgery |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | UK | Expert knowledge | British Society for Surgery of the Hand; British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons | Plastic surgery |

| National Clinical Programme in Surgery34 | Ireland | Professional bodies | National Clinical Programme in Surgery | None |

N/A, not applicable.

Specialty and surgical procedure

Papers related to a range of specialties including: anaesthetics, gastrointestinal surgery, gynaecology, breast surgery, ophthalmology, trauma and orthopaedics, plastic surgery, ears, nose and throat (ENT) surgery, vascular surgery, urology, dermatology, maxillofacial surgery, endoscopy and emergency surgery. Four papers produced guidance specific to dermatology, three papers trauma and orthopaedics, two for plastic surgery and one for urology. Four papers focused on the provision of anaesthetics in the non-operating theatre setting.

Four documents focused on the delivery of specific procedures. These included open hand fractures (not tuft fractures)31, lacerations with extensor tendon involvement33, transperineal prostate biopsy31 and excision of low-risk basal cell carcinoma (BCC)24. Six papers listed some example procedures that may be appropriate to be performed in the non-operating theatre setting (Supplementary materials, Table S3).

Rationale for development of guidance

Eleven documents provided a rationale for publication of the guidance. Five aimed to provide general guidance for personnel delivering procedures outside an operating theatre, four provided guidance specifically regarding the accreditation or design of facilities and two aimed to improve the quality of the delivery of procedures in the non-operating theatre setting. For example, ‘(it is) hoped that implementation of this guidance will lead to improvements in the quality of the management of low-risk BCC in the community’24 and ‘(the guidance authors) hope that these guidelines will inspire and encourage hand surgeons everywhere to make the case for change in their own services, striving for efficient, resilient, safe and effective hand surgery for the benefit of our patients’33.

Procedures recommended for delivery in a non-operating theatre setting

General terms or phrases that were used to describe procedures that may be suitable for the non-operating theatre setting included ‘minor surgery performed under topical or local anaesthesia not involving drug-induced alteration of consciousness other than minimal preoperative antianxiety medication’23, ‘wide awake local anaesthesia and no tourniquet’30, ‘cutaneous surgical procedures’20 and ‘minimal access interventions’25.

Seven documents gave general guidance on the delivery of procedures in a variety of specialties and reported examples of procedures that would be appropriate for the non-operative theatre setting (Table 2). These included excision of skin lesions22–24,34, carpal tunnel release18,20,22,30,35 and vasectomies27,31. Guidance from the American Academy of Dermatology suggested ‘cutaneous surgical procedures with local, topical or regional anaesthesia… performed with additional administration of sedative or analgesic drugs, particularly intravenous administration’20 were suitable for the non-operating theatre setting.

List of terms and definitions used to describe non-operating theatre settings

| Document . | List of terms for the non-operating theatre setting . | List of verbatim text definitions of the non-operating theatre setting . |

|---|---|---|

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | Non-operating room anaesthetizing locations | Locations outside an operating room |

| Humphreys et al.25 | Procedure rooms Treatment rooms | Outside a ventilated operating theatre Outside the conventional operating theatre Areas without specialist ventilation |

| Grobler et al.23 | Procedure room Individual examination room Office-based surgery Medical practitioner's office | Location where an operation or procedure carried out in a medical practitioner's office or outpatient department, other than a service normally included in a consultation, which does not require treatment or observation in a day surgery or procedure centre (facility) or unit, or as a hospital inpatient. The procedure room should be situated in an area away from the flow of heavy traffic to contain contaminated areas and ensure privacy |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | Procedure room | An operation that can be performed in a suitably clean area outside an operating theatre. The varying complexity of such procedures may require the commissioning of a specific environment and equipment beyond the expectation of a standard outpatient room (for example endoscopy or patient hysteroscopy suites) |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | Non-theatre environment Non-theatre settings Procedure rooms Non-operating room facilities delivering anaesthesia and sedation | Non-theatre settings within the hospital in which anaesthesia services are provided |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Facility | Wherever procedural sedation and/or analgesia for diagnostic and interventional medical, dental and surgical procedures are administered |

| Van Demark et al.30 | Minor procedure room Office procedure room In-office procedure room | Class A: local anaesthesia, Class B: minor/major surgery with sedation, Class C: general/regional anaesthesia; a Class A case in South Dakota requires a minimum of 15 ACH and a Class C case requires 20 ACH |

| Drake et al.20 | Office surgical facilities Class I facilities Class II facilities | An office or facility in which surgical procedures are performed; A. Class I facilities are those in which surgical procedures are performed with the patient under topical, local or regional anaesthesia. Oral or intramuscular sedatives or analgesics may supplement the anaesthesia. B. Class II facilities are those that offer the additional administration of intravenous sedative or analgesic drugs. Class II facilities require a higher level of safety, and resuscitation equipment is required |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | Non-main theatre sites Minor procedure room | Non-main theatre sites are other surgical settings that do not meet the criteria of: high rate of air exchange, typically ranging between 15 air exchanges per hour and laminar flow, a positive pressure system, with vents as required, and protocols around entry and exit of staff during procedures. Non-main theatre sites may be adapted clinical spaces or rooms, rather than purpose built, and may be staffed by non-theatre staff, such as outpatient nurses with appropriate training. Such facilities may be at sites remote from main hospitals, such as local care centres, community hospitals or primary care practices |

| Document . | List of terms for the non-operating theatre setting . | List of verbatim text definitions of the non-operating theatre setting . |

|---|---|---|

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | Non-operating room anaesthetizing locations | Locations outside an operating room |

| Humphreys et al.25 | Procedure rooms Treatment rooms | Outside a ventilated operating theatre Outside the conventional operating theatre Areas without specialist ventilation |

| Grobler et al.23 | Procedure room Individual examination room Office-based surgery Medical practitioner's office | Location where an operation or procedure carried out in a medical practitioner's office or outpatient department, other than a service normally included in a consultation, which does not require treatment or observation in a day surgery or procedure centre (facility) or unit, or as a hospital inpatient. The procedure room should be situated in an area away from the flow of heavy traffic to contain contaminated areas and ensure privacy |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | Procedure room | An operation that can be performed in a suitably clean area outside an operating theatre. The varying complexity of such procedures may require the commissioning of a specific environment and equipment beyond the expectation of a standard outpatient room (for example endoscopy or patient hysteroscopy suites) |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | Non-theatre environment Non-theatre settings Procedure rooms Non-operating room facilities delivering anaesthesia and sedation | Non-theatre settings within the hospital in which anaesthesia services are provided |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Facility | Wherever procedural sedation and/or analgesia for diagnostic and interventional medical, dental and surgical procedures are administered |

| Van Demark et al.30 | Minor procedure room Office procedure room In-office procedure room | Class A: local anaesthesia, Class B: minor/major surgery with sedation, Class C: general/regional anaesthesia; a Class A case in South Dakota requires a minimum of 15 ACH and a Class C case requires 20 ACH |

| Drake et al.20 | Office surgical facilities Class I facilities Class II facilities | An office or facility in which surgical procedures are performed; A. Class I facilities are those in which surgical procedures are performed with the patient under topical, local or regional anaesthesia. Oral or intramuscular sedatives or analgesics may supplement the anaesthesia. B. Class II facilities are those that offer the additional administration of intravenous sedative or analgesic drugs. Class II facilities require a higher level of safety, and resuscitation equipment is required |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | Non-main theatre sites Minor procedure room | Non-main theatre sites are other surgical settings that do not meet the criteria of: high rate of air exchange, typically ranging between 15 air exchanges per hour and laminar flow, a positive pressure system, with vents as required, and protocols around entry and exit of staff during procedures. Non-main theatre sites may be adapted clinical spaces or rooms, rather than purpose built, and may be staffed by non-theatre staff, such as outpatient nurses with appropriate training. Such facilities may be at sites remote from main hospitals, such as local care centres, community hospitals or primary care practices |

ACH, air changes per hour.

List of terms and definitions used to describe non-operating theatre settings

| Document . | List of terms for the non-operating theatre setting . | List of verbatim text definitions of the non-operating theatre setting . |

|---|---|---|

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | Non-operating room anaesthetizing locations | Locations outside an operating room |

| Humphreys et al.25 | Procedure rooms Treatment rooms | Outside a ventilated operating theatre Outside the conventional operating theatre Areas without specialist ventilation |

| Grobler et al.23 | Procedure room Individual examination room Office-based surgery Medical practitioner's office | Location where an operation or procedure carried out in a medical practitioner's office or outpatient department, other than a service normally included in a consultation, which does not require treatment or observation in a day surgery or procedure centre (facility) or unit, or as a hospital inpatient. The procedure room should be situated in an area away from the flow of heavy traffic to contain contaminated areas and ensure privacy |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | Procedure room | An operation that can be performed in a suitably clean area outside an operating theatre. The varying complexity of such procedures may require the commissioning of a specific environment and equipment beyond the expectation of a standard outpatient room (for example endoscopy or patient hysteroscopy suites) |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | Non-theatre environment Non-theatre settings Procedure rooms Non-operating room facilities delivering anaesthesia and sedation | Non-theatre settings within the hospital in which anaesthesia services are provided |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Facility | Wherever procedural sedation and/or analgesia for diagnostic and interventional medical, dental and surgical procedures are administered |

| Van Demark et al.30 | Minor procedure room Office procedure room In-office procedure room | Class A: local anaesthesia, Class B: minor/major surgery with sedation, Class C: general/regional anaesthesia; a Class A case in South Dakota requires a minimum of 15 ACH and a Class C case requires 20 ACH |

| Drake et al.20 | Office surgical facilities Class I facilities Class II facilities | An office or facility in which surgical procedures are performed; A. Class I facilities are those in which surgical procedures are performed with the patient under topical, local or regional anaesthesia. Oral or intramuscular sedatives or analgesics may supplement the anaesthesia. B. Class II facilities are those that offer the additional administration of intravenous sedative or analgesic drugs. Class II facilities require a higher level of safety, and resuscitation equipment is required |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | Non-main theatre sites Minor procedure room | Non-main theatre sites are other surgical settings that do not meet the criteria of: high rate of air exchange, typically ranging between 15 air exchanges per hour and laminar flow, a positive pressure system, with vents as required, and protocols around entry and exit of staff during procedures. Non-main theatre sites may be adapted clinical spaces or rooms, rather than purpose built, and may be staffed by non-theatre staff, such as outpatient nurses with appropriate training. Such facilities may be at sites remote from main hospitals, such as local care centres, community hospitals or primary care practices |

| Document . | List of terms for the non-operating theatre setting . | List of verbatim text definitions of the non-operating theatre setting . |

|---|---|---|

| American Society of Anesthesiologists29 | Non-operating room anaesthetizing locations | Locations outside an operating room |

| Humphreys et al.25 | Procedure rooms Treatment rooms | Outside a ventilated operating theatre Outside the conventional operating theatre Areas without specialist ventilation |

| Grobler et al.23 | Procedure room Individual examination room Office-based surgery Medical practitioner's office | Location where an operation or procedure carried out in a medical practitioner's office or outpatient department, other than a service normally included in a consultation, which does not require treatment or observation in a day surgery or procedure centre (facility) or unit, or as a hospital inpatient. The procedure room should be situated in an area away from the flow of heavy traffic to contain contaminated areas and ensure privacy |

| British Association of Day Surgery27 | Procedure room | An operation that can be performed in a suitably clean area outside an operating theatre. The varying complexity of such procedures may require the commissioning of a specific environment and equipment beyond the expectation of a standard outpatient room (for example endoscopy or patient hysteroscopy suites) |

| Royal College of Anaesthetists32 | Non-theatre environment Non-theatre settings Procedure rooms Non-operating room facilities delivering anaesthesia and sedation | Non-theatre settings within the hospital in which anaesthesia services are provided |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists26 | Facility | Wherever procedural sedation and/or analgesia for diagnostic and interventional medical, dental and surgical procedures are administered |

| Van Demark et al.30 | Minor procedure room Office procedure room In-office procedure room | Class A: local anaesthesia, Class B: minor/major surgery with sedation, Class C: general/regional anaesthesia; a Class A case in South Dakota requires a minimum of 15 ACH and a Class C case requires 20 ACH |

| Drake et al.20 | Office surgical facilities Class I facilities Class II facilities | An office or facility in which surgical procedures are performed; A. Class I facilities are those in which surgical procedures are performed with the patient under topical, local or regional anaesthesia. Oral or intramuscular sedatives or analgesics may supplement the anaesthesia. B. Class II facilities are those that offer the additional administration of intravenous sedative or analgesic drugs. Class II facilities require a higher level of safety, and resuscitation equipment is required |

| British Society for Surgery of the Hand16 | Non-main theatre sites Minor procedure room | Non-main theatre sites are other surgical settings that do not meet the criteria of: high rate of air exchange, typically ranging between 15 air exchanges per hour and laminar flow, a positive pressure system, with vents as required, and protocols around entry and exit of staff during procedures. Non-main theatre sites may be adapted clinical spaces or rooms, rather than purpose built, and may be staffed by non-theatre staff, such as outpatient nurses with appropriate training. Such facilities may be at sites remote from main hospitals, such as local care centres, community hospitals or primary care practices |

ACH, air changes per hour.

Four papers discussed wholly the delivery of specific procedures in the non-operating theatre setting including, wound washout and closure with splinting of the fracture28, BCC excision or biopsy24, repair of lacerations with extensor tendon involvement33 and transperineal prostate biopsy28. The British Society of Surgery for the Hand (BSSH) classified a ‘minimal procedure’28 as being suitable for the non-operating theatre setting.

Six documents made recommendations that the delivery of surgery or anaesthesia in the non-theatre setting was not suitable for all patients. All documents (n = 6)16,20,25,28,32,36 recommended consideration of individual patient or operative factors. Three papers recommended that the ultimate decision to operate in the non-theatre setting lies with the surgeon following consideration of these factors20,32,36. Three papers stressed the importance that more complex operations, such as those involving implantation or metalwork, should stay in the conventional operating theatre setting16,25,28.

Setting specifications

Twenty different terms were used across the 17 included documents to describe settings outside of the operating theatre. These included ‘area without specialist ventilation’25, ‘minor procedure room’16,30 and ‘office surgical facilities’20,36. Eight documents did not provide a definition for non-operating theatre terms21,23,25,26.

Fourteen documents gave some guidance about setting specifications. The most frequent recommendation was (n = 11)16,20,23,25,26,29,30,32–34,36 the need for lighting, with five specifying ‘sufficient’20,36, ‘adequate’25,29 or ‘appropriate’ lighting20,26. Of the 11, three also recommended a back-up lighting system20,29,36.

Eight documents made limited recommendations on venue size. These were largely for the room to be of adequate size (n = 7)21–23,26,29,32,36. For example, describing the need for ‘sufficient space to accommodate necessary equipment and personnel and to allow expeditious access to the patient, anaesthesia machine (when present) and monitoring equipment’29 and being ‘large enough to allow easy access to the patient and storage for supplies and other equipment’23. One document went further, and suggested specific measurements: ‘a minimum of 250 sq. ft’30.

Sterility or sanitation recommendations were made in seven guidance documents. These included recommendations about where rooms should be situated in one document (for example: the ‘procedure room should be situated in an area away from the flow of heavy traffic to contain contaminated areas’23). Some general guidance was given for levels of cleanliness in four documents (for example ‘a level of cleanliness appropriate for the type of procedure performed’36). Guidance in five documents discussed appropriate features of ‘scrub-up’ facilities, including their location25, and the need for hands-free taps25,36 and disposable towels20,25,36. One document specified that it was appropriate for patients to wear their own clothes16.

Four documents gave recommendations regarding room ventilation. Of these, most (n = 3) specified requirements for natural ventilation with protective coverings to prevent the entry of insects20,25,36. Only one provided further detail. Humphreys et al. recommended ‘where minimal access interventions with general anaesthesia are undertaken, 15 air changes per hour are required, similar to that specified for anaesthetic rooms in conventionally ventilated theatre suites, to minimize staff exposure to anaesthetic gases’25.

Other recommendations about setting included, the need for back-up power (n = 5)20–22,25,36, recovery areas (n = 5)20–22,26,32, appropriate waste disposal (n = 6)20,23,25,26,29,36, occupational health guidelines (n = 5)1,3,16,17,21, use of surgical checklists (n = 3)16,34 and emergency protocols (n = 6)20,21,23,26,32,36.

Equipment

Fourteen documents specifically outlined what equipment should be present in non-operating theatre settings. Ten discussed surgical instruments, although this was not specifically related to the out-of-theatre settings, rather guidance applicable to any context in which surgical instruments are used16. Four documents recommended specific haemostasis equipment20,23,29,34,36. Other equipment recommended by documents included patient warming devices32, access to X-rays intraoperatively28, suction23,26 and personal protective equipment (n = 4)16,23,25,36. Five documents made recommendations for resuscitation equipment including advanced airway equipment (n = 4)20,26,32,36, defibrillator (n = 4)26,29,32,36 and source of oxygen (n = 5)20,26,29,32,36.

Staffing requirements

Five documents specified staffing requirements, including (n = 4) minimum number of staff members from two21,28 to three26,34, or ‘depending on complexity of the surgery’16. Six documents described qualifications or training required to deliver procedures in the non-operating theatre setting. Four said that surgeons should have appropriate training and evidence of ongoing professional development22–25 and one recommended that the surgeon should be allowed to perform the procedure by law22. Two documents required specific training or supervision by a competent surgeon for the performance of named procedures28,33. In guidance related to anaesthesia, documents talked about need for competency, understanding26,32 and sufficient training32. Guidance about the wider team was given in 10 documents and focused on the provision of basic cardiopulmonary support and emergency support16,20,21,23,26,29,32,36, occupational hazards and exposure20,23,32,36, and understanding of facilities21,23,25,28,32.

Patient consent and information provision

Seven documents provided information or recommendations regarding patient information provision and consent. Guidance emphasized the importance of informed consent and the principles of shared decision-making. For example, ‘when informed consent is obtained, the patient (and family where appropriate) is given information about his or her condition, proposed treatment, procedure's potential benefit and drawbacks, alternative treatments’21 and ‘all patients (and relatives where appropriate and relevant) should be fully informed about the planned procedure and be encouraged to be active participants in decisions about their care’32.

Patient safety

Twelve papers provided guidance regarding patient safety for procedures in the non-operating theatre. Twelve documents talked about essential medications that should be available, including a full range of emergency medicine, for example reversal agents26,32,36, intravenous fluids20,36 and procedure-specific medication, for example for manipulating coagulation32. Guidance focused on the maintenance of an adequate anaesthetic and surgical record (n = 5)20,23,26,32,34 with regular or rolling audits of postoperative outcomes (n = 5)25,26,28,32,33 and the implementation of an established response plan in case of medical emergency (n = 6)20,21,23,26,32,36. Three papers stressed the importance of the use of surgical checklists16,32,34.

Discussion

Despite the need to provide innovative strategies to help clear the backlog of procedures in the NHS1, the delivery of appropriate surgical procedures outside of traditional operating theatres within the NHS is limited. This scoping review provides an analysis of contemporary clinical guidance documents for the provision of surgery outside of standard operating theatres, including the procedures that may be suitable and the requirements for such settings including staffing, equipment and patient consent. Overall, the guidance provided was limited. Documents provided information about some procedures suitable for delivery and broad setting specifications/equipment. Procedures appropriate for the non-operating theatre setting were commonly minor procedures to be performed under topical or local anaesthesia and not requiring general anaesthesia. Documents specified that settings should be of adequate size for all appropriate equipment and personnel, with considerations for lighting, waste disposal, ventilation and emergency equipment made. Staff should be appropriately trained and wear appropriate personal protective equipment. There should be maintenance of good surgical records and implementation of appropriate occupational health and safety guidelines. However, guidance lacked specificity, and used heterogenous terminology to describe these settings. It is evident that further guidance with clear standardized terminology is required to inform development of guidance for delivery of suitable procedures in non-operating theatre settings. The optimum parameters for various forms of healthcare delivery are defined by the Health Technical Memoranda in the UK. These describe national standards for issues such as ventilation, sterile pack storage facilities and surgical waste disposal that must be considered when designing surgical and operative facilities35,37–40. Future guidance must consider how the Health Technical Memoranda might be met in the non-operating theatre setting.

Countries such as the USA and Canada have been utilizing these settings for several years. In 2005, 10 million office-based procedures were performed23. There are significant benefits to the use of the non-operating theatre setting for minor procedures. The experience of a plastic surgery unit in Saint John, Canada, is that the non-operating theatre setting is more cost-efficient, minimizes unnecessary use of the main theatres and is more environmentally friendly, reducing the amount of clinical waste produced16. A study of carpal tunnel releases demonstrated that operations performed in main theatres were four times as expensive and half as efficient as the non-operating theatre setting41. This was reflected in the documents included in this scoping review, which emphasized the cost-effectiveness of the non-theatre setting. The National Clinical Programme for Surgery reported their projected operation cost per procedure in the non-operating theatre setting as 154.4 euros34. Moreover, Van Demark et al. remarked that ‘patient satisfaction has been high: 95% of the patients rate their experience the same or better than the dentist, 99% would do wide-awake anaesthesia again in the office and 99% would recommend to a friend or family member’30. Undoubtedly, there remains a requirement for certain patient groups and types of surgery, particularly operations with increased complexity, to remain in standard operating theatres16. However, consideration of patients and procedures that may be appropriate for out-of-theatre delivery may be a much-needed opportunity to increase operating theatre capacity and reduce waiting lists.

There are several perceived disadvantages associated with the non-theatre setting including, but not limited to, safety, potential increased infection risks and re-organization costs. Guidance documents largely felt that the non-operating theatre setting posed a low risk of healthcare-related infections12,16,30 and emphasized guidance to reduce rates of infection16,25,28,30,33. This reflects the current literature, for example, a multicentre study of carpal tunnel releases performed in the non-operating theatre setting reported 0.4% superficial infections and no deep infections12. To minimize hospital-related infections, documents made recommendations for the non-operating theatre setting to be suitably clean and have an area for sterile set-up. Moreover, documents recommended staff should wear appropriate PPE, perform a surgical scrub before surgery, and use surgical safety checklists and single-use surgical instruments. Specifically designed areas for the performance of surgery in the non-operating theatre setting would be ideal. However, it is likely that areas not originally designed to undertake operations will be repurposed and considerations must be made to minimize these safety and infection control risks. Such areas will be required to meet the national standard requirements for operating theatres35,37–40. Future guidance should make recommendations for how repurposed or specifically designed rooms may or may not meet these standards. Moreover, further challenges, such as the balance between single-use and reusable surgical instruments, will need to be overcome to ensure that the carbon footprint is minimized.

This review is timely due to rising interest in the movement of procedures to the out-of-theatre setting in response to COVID and increasing waiting lists. To ensure relevance, a cut-off of 2010 was used in the electronic database search. The professional organization search and expert knowledge identified documents did not have a time limit and could have identified documents missed due to this cut-off.

However, there are a number of limitations to this scoping review. Primarily, the quality of guidance documents included in the review was limited. These ranged from publications devised through the experience of a single institution23 through to the guidance produced in collaboration with stakeholders including surgeons, anaesthetists, microbiologists, infection control experts, nurse practitioners, general practitioners and patient representatives16. Moreover, documents were published in disparate countries, with different legal standards and ethical interpretations, and focused on different specialties, both within surgery and from anaesthesia. This made synthesis of the results challenging, and conclusions must be drawn contextually. It is evident that the guidance is unclear and requires improved standardization and defined terminology to help inform stakeholders about the development of out-of-theatre surgical practices.

This scoping review documented significant heterogeneity in papers providing guidance regarding the non-theatre setting. It is evident that guidance requires standardization of terminology and definitions to help inform stakeholders about the development of non-theatre setting practices. The non-operating theatre setting may be a cost-effective and safe way to deliver essential minor surgical procedures under local or topical anaesthetic to appropriate patients, freeing up space in main theatres for the delivery of more complex operations, reducing waiting list times and optimizing sustainability issues. Further research should focus on the development of recommendations to guide NHS managers and clinicians about when this is appropriate and include guidance as to how non-theatre settings may be facilitated.

Funding

The authors have no funding to declare.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS Open online.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no data sets were generated and/or analysed for this study. This is a scoping review, and all the data used are taken from previously published material.

Author contributions

Maia Osborne-Grinter (Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Sian Cousins (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing), Jozel Ramirez (Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), James R. Price (Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing), Luca Lancerotto (Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing—review & editing), Matthew Gardiner (Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing—review & editing), Ronelle Mouton (Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—review & editing) and Robert Hinchliffe (Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—review & editing).