-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marie-Laure Charpignon, Shauna Onofrey, Yea-Hung Chen, Alex Rewegan, Medellena Maria Glymour, R Monina Klevens, Maimuna Shahnaz Majumder, Association between social vulnerability and place of death during the first 2 years of COVID-19 in Massachusetts, Age and Ageing, Volume 53, Issue 2, February 2024, afae018, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afae018

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We investigated the relationship between individual-level social vulnerability and place of death during the infectious disease emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic in Massachusetts. Our research represents a unique contribution by matching individual-level death certificates with COVID-19 test data to analyse differences in distributions of place of death.

Key Points

A person’s place of death depends on multiple factors, e.g. end-of-life wishes, urgency of illness, socio-economic status.

This research brief aims to generate hypotheses on the relationship between social vulnerability and place of death.

We investigated the relationship between individual-level social vulnerability and place of death during COVID-19 in MA, USA.

Our work represents a unique contribution by matching death certificates with test data to assess differences in place of death.

Differing odds of inpatient death by vulnerability suggest that dedicated training of clinical staff for emergencies is needed.

A person’s place of death depends on multiple factors, including end-of-life wishes, urgency of illness, socio-economic status and relative access to quality care [1]. While many people express a preference for dying at home [2], such a preference becomes secondary during emergencies, whereby different distributions of death locations across sociodemographic subgroups may indicate a need for resource reallocation.

Introduction

Studies regarding the relationship between social vulnerability and COVID-19 testing, incidence and mortality show that highly vulnerable individuals have suffered disproportionate pandemic-period morbidity and mortality [3, 4]; however, none investigated place of death. Here, for the first time, we assess the association between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) and place of death with more granular geographical resolution, by linking individual-level surveillance records and death certificates and further stratifying by residential zipcode. This descriptive research brief aims to generate hypotheses on the relationship between SVI and place of death.

Methods

Among decedents who tested positive for COVID-19, we quantified the crude and adjusted association between zipcode-level SVI and place of death through four logistic regressions, contrasting each setting of death (inpatient, congregate setting, home and outpatient) with all others. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health MAVEN (Massachusetts Virtual Epidemiological Network) surveillance system provided COVID-19 case data from February 2020 to January 2022, inclusive. Death records obtained from the Division of Vital Statistics were matched with individual case-level data via six sociodemographic variables. Census tract-level SVI values obtained from the 2020 CDC data release were aggregated by zipcode. Census tracts were mapped to corresponding zipcodes utilising the 2020 crosswalk from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (Supplementary Material). To account for potential confounding in the place of death–SVI relationship, we controlled each logistic regression for sex, age at death, ethnicity, race, educational attainment, recency of the last positive COVID-19 test (binary variable: 1 if within a 30-day window preceding death, 0 otherwise) and temporal pandemic factors (binary indicators for each of four epidemic waves; Supplementary Material). The main analysis included all Massachusetts deaths, irrespective of residential status and cause of death. Three sensitivity analyses were conducted: the first was restricted to individuals whose death certificate had COVID-19 listed as the underlying cause, the second was restricted to state residents and the third considered state residents who died from COVID-19 as the underlying cause. We repeated similar analyses among individuals aged 65+ at the time of death (Supplementary Material). To assess the extent of heterogeneity in the evolution of testing rates both within and across SVI categories, we characterised the temporal evolution of testing rates in Massachusetts over the study period—at the state level, by city and town, and by area deprivation (Supplementary Material).

Results

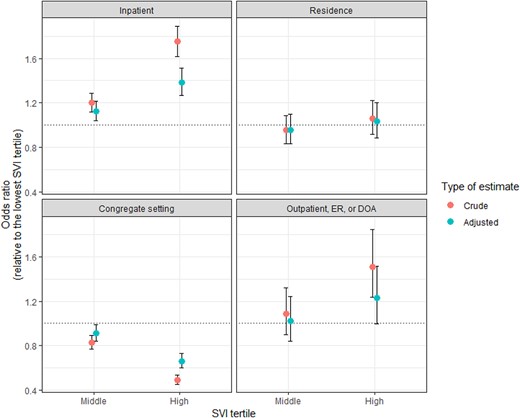

Between 1 March 2020 and 31 January 2022, 21,826 individuals with recent COVID-19 infection documented by testing or autopsy (Supplementary Material) died in Massachusetts (98.0% were residents); COVID-19 was the underlying cause for n = 14,409 (66.0%). Mortality patterns by SVI contrasted with the spatial distribution of the broader Massachusetts population: decedents with documentation of recent COVID-19 infection were more likely than Massachusetts residents overall to live in zipcodes with moderate SVI (51.1 versus 33.1% of living residents) and less likely to live in zipcodes with high SVI (29.2 versus 33.2%). After adjustment, odds that the death of a person recently infected with COVID-19 occurred in an inpatient setting (versus all others) were 1.12 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.04–1.22) and 1.39 (1.27–1.52) times higher among individuals residing in zipcodes of moderate and high SVI, respectively, than among their low-SVI counterparts. Adjusted odds of death in a congregate setting (e.g. nursing home, hospice) were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.84–0.99) and 0.66 (0.60–0.73) times lower among individuals living in zipcodes of moderate and high SVI, respectively (Figure 1). Notably, no statistically significant association between SVI and at-home or outpatient death appeared. Sensitivity analyses yielded similar results (Supplementary Material). Although the testing rate trajectories in cities and towns of the moderate SVI category were more heterogeneous than those of locations in the low or high SVI category, they generally followed that of Massachusetts as a whole (Supplementary Material).

Relationship between the SVI and place of death in Massachusetts, among decedents who previously tested positive to COVID-19. Each panel corresponds with a distinct setting of death: inpatient; home or residence; congregate setting; outpatient, emergency room (ER) or dead on arrival (DOA). Each panel captures the crude (red, left) and adjusted (blue, right) odds ratio associated with the two upper SVI tertiles (middle and high), relative to the lower tertile (reference), as measured through a logistic regression model with the setting of death as a binary outcome. The horizontal dashed line indicates an odds ratio of 1. Values below 1 (respectively, above 1) indicate a negative (respectively, positive) association, i.e. greater social vulnerability is related to a lower (respectively, higher) risk of death in the considered setting. Error bars represent the 95% CI for the estimated odds ratio.

Discussion

Beyond individual-level health and sociodemographic factors, differences in the odds of inpatient death may arise from delayed care-seeking and/or diagnosis, resulting in late admission to hospitals among individuals living in socially vulnerable communities. One likely explanation for the lower odds of congregate-setting death among individuals residing in zipcodes of high SVI is the geospatial distribution of nursing homes and long-term care facilities in Massachusetts; only 9.2% are in high SVI zipcodes (Supplementary Material). Differing odds of inpatient death by SVI suggest that dedicated training of clinical staff for emergencies [5] and reorganisation of healthcare services during recovery are needed [6]. Future research should explore differences in place of death and SVI over time to inform public health efforts for improved end-of-life care, especially among our most vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgements

M.-L.C., S.O. and R.M.K. had full access to all the data in the study. Thus, they take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. None of the authors has a conflict of interest to report.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

M.S.M. was supported in part by grant SES2200228 from the National Science Foundation. M.L.C. was supported in part by a doctoral fellowship from the MIT Harvard Broad Institute Eric & Wendy Schmidt Center. The CompEpi Dispersed Volunteer Research Network is sponsored in part by grant R35GM146974 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All analyses were run using R 4.2.1. Aggregated datasets mentioned in the Supplementary Material can be found on the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/CharpignonML/SocialVulnerability_MA/. Individual-level data can be obtained from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health upon request.

References

Author notes

R. Monina Klevens and Maimuna Shahnaz Majumder Senior Authors

Comments