-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ashley Macleod, Lucy Busija, Marita McCabe, Mapping the Perceived Sexuality of Heterosexual Men and Women in Mid- and Later Life: A Mixed-Methods Study, Sexual Medicine, Volume 8, Issue 1, March 2020, Pages 84–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2019.10.001

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

There is currently limited research that examines the meaning of sexuality at midlife and later life.

This study investigates how heterosexual men and women in mid- and later life perceive their sexuality and the factors that influence it.

Group concept mapping was used to produce a conceptual map of the experience of sexuality for heterosexual adults ages 45 years and above. Group concept mapping data were collected using 6 open-ended survey questions that asked about sexuality, intimacy, and desire. Thematic analysis was used to examine how participants perceived their sexuality to have changed as they aged. Thematic analysis data were collected using a single open-ended survey question.

Statements generated from 6 of the open-ended survey questions were rated by participants using a 5-point Likert scale for how important participants felt that each statement was to themselves personally. Participants responses to the seventh open-ended survey question were examined using thematic analysis to understand whether participants felt that their sexual experiences had changed over time and, if so, how they had changed.

Eight themes were identified across the different phases of group concept mapping. These were, in order of importance, partner compatibility, intimacy and pleasure, determinants of sexual desire, sexual expression, determinants of sexual expression, barriers to intimacy, sexual urges, and barriers to sexual expression. Seven areas of change were identified in terms of perceived changes to sexuality with age. These included changes to perspective, relationship dynamics, environment, behavior, body/function, sexual interest/desire, and sexual enjoyment.

The results highlight the prioritization of interrelationship dynamics in mid- and later life sexuality over sexual functioning and sexual urges. These findings may facilitate the development of new perspectives on how sexuality is experienced in the later years and provide new avenues for intervention in situations where sexual problems arise.

Introduction

Sexuality is an integral and constantly changing part of human experience.1–4 Research indicates that sexual expression is still desired by older adults and that they still consider themselves to be sexual beings.5–7 However, as people age, the quality of sexual experiences becomes increasingly more important than their frequency.8–10 This change indicates that the current emphasis of research and medicine on the maintenance or re-establishment of “youthful” sexual functioning and frequency of sexual behavior in later life may not accurately reflect the sexual priorities of older adults.11 The absence of a clear and consistent definition of sexuality in mid- and later life, however, makes it difficult to determine the actual sexual wants, needs, and experiences of older adults.

Current approaches to understanding sexuality in the later years often imply that declines in sexual activity frequency and sexual functioning are problematic side-effects of the aging process.12–14 In line with this assumption, much of the quantitative later-life sexuality research has focused on sexual activity frequency,15–17 sexual dysfunction prevalence,15,18 and the impact that changes in sexual functioning have on the sex lives of older adults.19–21 This research has been valuable in advancing our understanding of sexual dysfunction and for identifying how sexuality in mid- and later life correlates with a broad range of biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors. However, this approach may promote an overly biomedical view of sexuality to the exclusion of other data and risks influencing the interpretation of results so that the presence of sexual dysfunction and decreases in penile-vaginal intercourse frequency become evidence of an unsatisfactory sex life, despite evidence to the contrary.2,3,9–11,22

In contrast, qualitative studies often highlight the importance of intimacy, warmth, and closeness between partners as part of older adults’ sexual experiences.2,3,9–11 For example, a study by Ménard et al22 asked men and women over the age of 60 in long-term relationships to describe their experiences of “great sex.” In their descriptions, participants focused on the role of relationship dynamics, partner availability, openness to new experiences, and overcoming learned ageism in their experiences, as opposed to sexual activity frequency, intercourse duration, or sexual functioning capacity in a sexual encounter. These results suggest that the current tendency to pathologize any decrease in penile-vaginal intercourse (thus equating optimal sexual functioning with the presence of a satisfying sex life23–25) may not accurately reflect the way that adults in mid- and later life perceive their own sexual experiences.

Despite evidence that the quality of sexual experiences is increasingly important to individuals as they age, there is still little research that explores what this means in terms of how sexuality is conceptualized by adults in the late stages of life.26,27 This suggests that crucial pieces of the sexuality puzzle may be missing in terms of how we understand sexuality in both mid- and later life and how we treat sexual and/or relationship problems. These gaps in our understanding have significant implications for understanding healthy sexuality in later life, the topics that researchers choose to focus on, and how researchers and health professionals understand the role of intimacy and non-penetrative sexual expressions in the sex lives of older adults.

To better understand how sexuality is conceptualized by heterosexual men and women in mid- and later life, it would be helpful to examine the sexual experiences of these adults in a broad, open-ended way. Because the experience of sexuality is highly personal, giving individuals the chance to describe these experiences in their own words allows for a greater depth of understanding of those experiences than a yes/no answer. Qualitative and mixed-method approaches, such as thematic analysis (TA) and group concept mapping (GCM), are often used to better understand the experiences or perspectives of individuals.28

Group concept mapping is a mixed-methods, multiphase approach to understanding complex social phenomena and generating a conceptual framework of a topic by engaging directly with the population under investigation.29 GCM is an approach that can integrate differing viewpoints from individuals with various attitudes, experiences, and characteristics.29 As such, GCM is well suited to examine heterogeneous populations such as heterosexual men and women over the age of 45.

Thematic analysis is a qualitative methodology that can be used to examine whether any underlying patterns are present in how a population discusses a topic of interest.30 Because GCM produces a conceptual map of how ideas interrelate rather than identifying thematic patterns in responses across a sample population, TA is a more appropriate methodological approach to uncovering similarities within groups.

This paper aims to use the voices of heterosexual adults ages 45 years and above to obtain a high-level understanding of how sexuality is conceptualized in mid- and later life, identify the level of importance placed on the different themes contained within this conceptualization, and provide further clarity with regard to whether adults in midlife and later life have perceived any changes to their sexual experiences as they have aged. In this study, GCM was used to produce a conceptual map reflecting the lived experiences of sexuality for heterosexual adults in mid- and later life, and TA was used to examine how heterosexual men and women in mid- and later life perceived changes to their sexuality over time. For this study, it was decided that individuals who do not identify as heterosexual would not be included and that sample subgroups (ie, men/women, midlife/later life) would not be examined separately, despite the presence of recognized differences in the sexual experiences for these cohorts. These investigations are currently beyond the scope of this study; however, it is hoped that the results of this study can help to provide a framework for future research in these areas in a way that helps improve the way that comparisons are made between different cohorts.

Methods

This study was divided into 2 parts: a GCM exercise and a TA of perceived changes to sexuality with increasing age. The GCM utilized the thoughts and experiences of heterosexual adults age 45 and above to develop an overarching conceptual “map” of sexuality in mid- and later life that identifies

The major themes that describe the sexual experiences of heterosexual adults 45 years and older and the determinants that influence these experiences

The interrelationships among the themes found above

How these themes are prioritized by heterosexual adults in mid- and later life

In the TA, patterns of perceived changes to sexuality and sexual experiences of heterosexual men and women in mid- and later life were investigated. The group mapping exercise is discussed first, followed by a discussion of the TA. Because GCM is not a widely used methodology, an overview of the methodological approach is presented before presenting a description of the study methods.

Group Concept Mapping

Group concept mapping methodology was used to develop a conceptual model of sexuality in midlife and beyond. Because GCM is an iterative and intensive process of identifying similarities in how a concept is understood by a group of individuals,29,30 a decision was made to produce an overarching conceptual map of sexuality for both men and women across mid- and later life cohorts, with the expectation that further research would be needed to more closely examine differences between these cohorts. The process of GCM is comprised of 3 major phases: data collection, data structuring (sorting) and rating, and data analysis.29 It is not necessary for the same participants to take part in all 3 phases nor is it problematic for the same participants to participate in all phases of the study,31 as the 3 phases are structured and analyzed independently of each other while remaining interconnected.

In the data collection phase, qualitative methods are used to understand experiences in relation to the topic of interest. The information is then consolidated to identify unique statements describing the concept of interest. In the second phase, the statements are presented back to participants, who are asked to sort the statements into themes by grouping the statements together in a way that they feel makes sense. Rosas and Kane32 recommended using between 20 and 30 sorters for optimal results in the statistical analysis phase. When the sorting task has been completed, participants are asked to reflect on the meaning of statements in each grouping and to suggest a short descriptive label that captures the essence of the grouping. Participants are then asked to rate the relative importance of each statement on a Likert-type scale. In the final phase, the data from the sorting and rating tasks are subjected to multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis to identify clusters of related statements and to calculate the average importance of different clusters. The results of the quantitative analysis are then presented as a pictorial concept map of major themes (clusters) that describe the concept of interest and show interrelationships between the themes. Details of the GCM process utilized in the current study are presented in the following sections.

Phase 1. Data Collection

Participants

Forty participants took part in the data collection phase (43% men, 57% women; mean age = 65 years; SD = 7.97) (Table 1 ). Eligible participants were community-dwelling men and women 45 years of age or older who identified as heterosexual, who lived in Australia currently, and who could read and write English competently. The age cutoff was set at 45 years to align with cutoff points for midlife in the guidelines set by the United Nations.33 No restrictions were set for current relationship status, ethnicity, or the presence of any chronic health conditions. This was done so that a broad range of perspectives from the population of interest could be sampled, thus increasing the likelihood that the resultant model would be as broadly inclusive of the wider population.

| . | Phase 1 . | Phase 2 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | |

| Men | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 1 (14) | 3 (30) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 6 (86) | 6 (60) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Australia | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Women | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 3 (21) | 6 (67) | 9 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 9 (64) | 3 (33) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Country | ||||||

| Australia | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| . | Phase 1 . | Phase 2 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | |

| Men | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 1 (14) | 3 (30) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 6 (86) | 6 (60) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Australia | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Women | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 3 (21) | 6 (67) | 9 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 9 (64) | 3 (33) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Country | ||||||

| Australia | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| . | Phase 1 . | Phase 2 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | |

| Men | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 1 (14) | 3 (30) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 6 (86) | 6 (60) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Australia | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Women | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 3 (21) | 6 (67) | 9 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 9 (64) | 3 (33) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Country | ||||||

| Australia | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| . | Phase 1 . | Phase 2 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | 45–64 y of age, n (%) . | 65+ y of age, n (%) . | Total . | |

| Men | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 1 (14) | 3 (30) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 6 (86) | 6 (60) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Australia | 6 (86) | 10 (100) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 |

| Women | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married without children | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Married with children | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Divorced | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Separated | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Widowed | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living alone | 3 (21) | 6 (67) | 9 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with partner | 9 (64) | 3 (33) | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Living with children and/or parents | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Shared accommodation with non-family | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

| Country | ||||||

| Australia | 8 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Netherlands | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| New Zealand | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Spain | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| United States | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mauritius | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Data unavailable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 15 |

Materials

Participants were asked to complete a survey that contained 7 open-ended focus questions (Table 1). The first 6 open-ended focus questions of this survey were used in phase 1 of the study. These 6 questions asked participants about their views on what sexuality, intimacy, and sexual desire meant to them currently; whether they felt that anything currently prevented them from being able to express their sexuality and what these obstacles were; what they felt was of particular importance to their own sexual expressions at present; and what they currently perceived to be erotic (Table 1). The questions were developed using the current literature on sexuality in mid- and later life as well as existing later life sexuality scales (eg, Geriatric Sexuality Inventory,34 Senior Adult Sexuality Scales35), the input of 2 psychologists with experience in the areas of sexuality and aging, and a biostatistician experienced in GCM. The 6 questions were designed to gather information about the way that individuals thought, felt, and interacted with their sexuality currently, including the experiences of desire and intimacy. No limits were set on the type or length of responses that participants could give in response to the focus questions. A comments section was included to allow participants to provide additional notes about topics of sexuality that they felt were not captured by the focus questions.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained for all phases of the study from the University Human Research Ethics Committee prior to phase 1 data collection. Informed consent for phase 1 was obtained prior to the start of the study. Prior to data collection, participants were provided with an informative letter that outlined the nature of the study, including information about the type of sensitive information collected, preservation of participant anonymity, data storage procedures, and how participants could withdraw from or raise concerns about the study. Participants were recruited from across Australia using a promotional strategy that relied predominantly on radio interviews, as well as media coverage in the form of news articles in printed news publications and online media. No incentives or tokens of appreciation were offered to participants for this study. Interested individuals were invited to contact the researchers directly, who then assessed the prospective participants against the eligibility criteria. During this initial assessment, participants were also queried about the preference for data collection method (online or via a postal pack). Participants who opted for the online data collection option were referred to the online survey tool Qualtrics software, Version 10.2016 (Qualtrics; Provo, UT). Participants who expressed a preference for a pen-and-paper format were sent a data collection pack that included instructions for how to complete the data collection task, a data collection sheet, and a self-addressed reply-paid envelope. At the end of the survey, participants were provided with the contact details of relevant help organizations in case they found the experience of reflecting on their sexuality distressing.

The data were collected via open-ended survey responses. Responses from all participants across all questions were consolidated in a single Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA). When multiple ideas were present in a response, these ideas were separated into single-idea statements. For example, a participant could have listed multiple things as being important in response to the question, “What kinds of things are most important to you in terms of sexual expression?” Each point listed was separated into a single-idea statement for coding. Each single-idea statement was then summarized using a single word by the first author (A.M.) to capture the core meaning of the statement. Each single statement summary was then used to produce a list of overarching themes. When a theme had been assigned to each item, all items were sorted using the identified themes and examined collectively by the 3 authors to identify redundancies within the themes. Redundancies were identified as any statement that shared the same meaning as another statement, as agreed upon by all 3 authors. After consolidation and removal of redundancies, the remaining unique statements were reviewed by the first author for correct spelling and grammar, and, where necessary, minor changes were made to improve readability prior to using the statements in the next phase.

Phase 2. Sorting and Rating

Participants

Twenty-five individuals took part in phase 2 (40% men, 60% women; Table 1). Because of an error in collection of demographic data, only sex and age cohort data were available for phase 2. Participants from phase 1 that wished to be contacted about future recruitment for the study were invited to take part in phase 2 via email, and new participants were recruited using radio and other media outlets. Due to the anonymous nature of the study, no information is available on how many participants from phase 1 also took part in phase 2. All eligibility criteria and recruitment approaches used in phase 1 were repeated in phase 2 (see phase 1 participants discussion, above).

Materials

Participants who chose to participate using a post pack were provided with a participant information letter, an instruction sheet, a set of statement cards (one card for each unique statement from the brainstorming phase), a set of blank envelopes, a rating task activity sheet, and a self-addressed reply-paid envelope. For online participants, the same information and tasks were presented in electronic form using the online survey tool Qualtrics software, Version 10.2016.

Procedure

Informed consent for phase 2 was obtained prior to commencement of the study. Participants were asked to complete a sorting task followed by a rating task. In the sorting task, participants were presented with the unique statements identified in phase 1 and asked to arrange statements into groups of items that they felt were similar in meaning. Participants were directed to create between 3 and 15 groups of statements and were advised that no group should contain only 1 statement, and no group should be made up of items deemed “miscellaneous.” The decision to request between 3 and 15 groups was made to optimize nuanced representation of sexuality in midlife and beyond while keeping group numbers manageable for participants. Participants were requested to have more than 1 item in each group to encourage them to think about the similarities and differences in the ideas captured in statements. The decision to request that no group contain only a single item was made to encourage participants to think about how each statement interconnected with others. No other instructions were provided to participants in terms of how to sort the statements. After participants had sorted all statements into groups, they were directed to name each of the groups. Participants were asked to provide names that best represented the overall theme of statements in each of the groups, but no further direction was given in terms of naming conventions. The participants who completed the sorting task by post were instructed to place each group of statements into a separate envelope, seal the envelope, and write the label describing the group of statements on the envelope before posting the results back to researchers. After completing the sorting task, participants were asked to rate each statement on how important they felt that statement was to themselves personally on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, and 5 = extremely important). Again, no token of appreciation or financial incentive was offered to participants.

Phase 3. Statistical Analyses

The sorted data were used to produce individual sort matrices for each participant in a Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet. The sort matrices had the number of rows and columns equal to the number of statements used in the sorting task and had a 1 for any pair of items that were sorted in the same group by a given participant and 0 for any pair of items that were sorted into separate groups. The individual sort matrices were then combined to produce a composite dissimilarity matrix for the entire sample. A dissimilarity matrix calculates a numerical value that represents the amount of (dis)similarity between each statement using the chi-square test of equality for 2 sets of frequencies. In a dissimilarity matrix, smaller numbers indicate that statements appear together in sort groups more often, and larger numbers indicate that statements do not often appear together in sort groups.

The composite dissimilarity matrix was then imported into SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM; Armonk, NY) and used to perform multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis. This produced a set of Euclidean distances that provided coordinate information about the relative spatial distance on a 2-dimensional plane between statements based on how often the statements were sorted together by the study participants. Results of the MDS were represented as a bivariate point map that showed the frequency with which statements were sorted together by participants. Items that were sorted together more often were distributed more closely together on the bivariate point map and produced smaller squared Euclidean distances. Thus, similar items appeared closer together on the point map, and less similar items appeared farther apart on the point map.

The MDS distances were used as input into a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) conducted using Ward’s algorithm in SPSS Statistics 23. HCA is preferred in GCM over other common clustering approaches (eg, principal component analysis or exploratory factor analysis) because it aligns more readily to the results of MDS and is less likely to produce overlapping themes or clusters.36 The goodness of fit of MDS solutions was assessed with Kruskal’s stress formula 1. Stress values represent how well the distances generated in MDS correspond to the values present in the dissimilarity matrix. A fair correspondence between the derived MDS solution and the initial dissimilarity matrix is consistent with stress values equal to .10 or lower, and a good correspondence is consistent with stress values equal to .05 or lower.37

The objective was to group items into clusters of conceptually similar statements. By using HCA, statement clusters that are most reflective of the groupings formed by participants are mathematically identified, thus minimizing researcher bias in the identification of themes. Cluster solutions with the number of clusters ranging from 3 to 15 were examined for how well items within a cluster appeared to represent a single theme. The decision to examine only solutions with 3 to 15 clusters was made to align with directions given to participants during the sorting task to sort statements into between 3 and 15 groups. Each solution was examined jointly by the authors to determine whether the clustering of statements produced meaningful themes. Solutions were discarded if one or more of the following conditions were met: (i) 1 or more clusters within the solution contained only a single item, (ii) the solution contained conceptually overlapping clusters, or (iii) items within at least 1 cluster did not form a conceptually cohesive theme. The preferred cluster solution was the solution that optimally identified nuanced groupings of interpretable statements without repetition or redundancies among the identified clusters, as determined by the authors. A final cluster name was chosen using cluster names suggested by participants during the sorting task in conjunction with discussion of identified themes within each cluster by the author team. Once a cluster name was chosen, theme definitions were developed for each cluster that were representative of the type of statements captured within the cluster and other statements that would be considered conceptually similar.

Data collected from the rating task were used to calculate mean rating scores for each statement across all participants. The statement ratings were then used to produce mean importance ratings for each cluster. Following this, the final named cluster map, cluster definitions, and cluster importance ratings were presented to participants for review via the project newsletter. Participants were encouraged to contact the research team via e-mail to provide feedback on whether they felt that the results represented their own experiences of sexuality. No participants chose to return written feedback; however, 4 participants returned feedback via phone. The responses from participants confirmed that the themes and ratings presented were a good representation of their own thoughts and experiences in relation to sexuality in midlife and beyond. For example, a female participant age 74, commented that the model “covered most areas well.”

Thematic Analysis of Perceived Change to Sexual Experience with Increasing Age

Thematic analysis was used to examine whether participants perceived a change in their sexual experiences as they aged. TA allows researchers to use a systematic and iterative approach to identify patterns or repeating themes within the collected data.30,38 In this study, an inductive approach to TA was used whereby the identification of themes was data driven rather than theory driven.30

Participants

Refer to participant data in the earlier section on phase 1 of GCM.

Materials

Data were collected using a single open-ended question included in the survey during the GCM phase (“Do you feel that your sexuality has changed over time, and if yes, how is it different?”). This question was designed to allow participants to describe changes to their sexuality over time in their own words. No instructions were provided in terms of how participants should respond to this question.

Procedure

The data were collected via open-ended survey responses. Responses from all participants were consolidated in a single Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet. Responses were first examined for whether participants identified a perceived change in their sexual experiences compared to their earlier years. Where changes were detailed by participants, each idea was separated into a single-idea statement. These statements were then read and re-read (A.M.), and a code list was developed using an axial approach that reflected the main themes discussed in the statements. Statements were then re-examined using the code list, and final coding of the data was agreed upon by the author team. When the key themes relating to any changes to the sexual experiences of participants had been identified, responses in their original form were re-examined (A.M.) to develop a table of themes. Emergent themes were reviewed by the author team in meetings at regular intervals throughout the thematic analysis process and again at the end of the TA to ensure agreement on the identified themes and confirm that all pertinent topics were captured.

Results

Group Concept Mapping

A total of 708 single-idea statements were generated using the responses to the focus questions. After removing repeated ideas, 75 unique statements were identified. These statements represented both attitudes and experiences relating to sexuality, as well as determinants that influence sexual experiences. Statements encompassed a range of sexual behaviors, sexual attitudes, sexual and relational preferences, and barriers to sexual expression. A full list of unique statements can be found in Table 2 . The 75 unique statements formed the basis of the sorting and rating tasks in phase 2. Sorting data were combined in a dissimilarity matrix and a set of Euclidean distances was generated using multidimensional scaling (Kruskal’s stress value = .07). Kruskal’s stress values indicated a fair correspondence between the raw data and distances between points on the bivariate point map.

Distribution of clustered statements and mean importance scores across identified clusters

| Cluster . | ID . | Statement . | Importance rating . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating . | Range . | Mean . | SD . | Cluster mean (SD) . | |||

| Partner compatibility | S2 | A sense of freedom of expression and appreciation of our differences | V | 2–5 | 4.00 | 0.83 | 4.37 (0.24) |

| S6 | Being able to communicate openly | V | 3–5 | 4.62 | 0.56 | ||

| S9 | Compatibility with each other | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.14 | ||

| S17 | Feeling cared for and valued | V | 2–5 | 4.37 | 0.83 | ||

| S18 | Feeling safe | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.87 | ||

| S21 | Freedom to be myself | V | 2–5 | 4.22 | 0.93 | ||

| S22 | Friendship/positive regard for you and your partner | V | 3–5 | 4.48 | 0.70 | ||

| S54 | Respect is important | V | 3–5 | 4.70 | 0.54 | ||

| S60 | Someone whose mind and personality are attractive | V | 3–5 | 4.55 | 0.57 | ||

| Intimacy and pleasure | S4 | An emotional response to a physical need of touch | V | 3–5 | 4.11 | 0.64 | 4.22 (0.31) |

| S5 | Anticipation for when we share those special moments together | V | 3–5 | 4.07 | 0.72 | ||

| S7 | Being able to hold and be held | V | 3–5 | 4.59 | 0.57 | ||

| S11 | Enjoying each other’s bodies | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S13 | Expression of desire or interest | M | 3–5 | 3.92 | 0.82 | ||

| S24 | General petting and intimacy | V | 2–5 | 4.11 | 0.80 | ||

| S25 | Giving and receiving pleasure | V | 3–5 | 4.37 | 0.68 | ||

| S34 | Knowing that my partner finds me attractive | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 0.95 | ||

| S43 | Mutual attraction and satisfaction | V | 3–5 | 4.51 | 0.64 | ||

| S44 | Mutual trust and understanding | V | 3–5 | 4.81 | 0.55 | ||

| S50 | Partner’s smile | V | 1–5 | 4.14 | 1.13 | ||

| S51 | Physical contact of some sort, hugging, holding hands, kissing | V | 2–5 | 4.55 | 0.80 | ||

| S53 | Playful activities leading up to being intimate (eg, pats and hugs throughout the day) | V | 3–5 | 4.25 | 0.81 | ||

| S55 | Romance | V | 3–5 | 4.14 | 0.71 | ||

| S56 | Sensuality | V | 3–5 | 4.18 | 0.68 | ||

| S59 | Sharing the things that are the most personal part of you | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S61 | Something that brings emotional satisfaction | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.73 | ||

| S63 | Speaking softly to each other is an important part of intimacy | M | 1–5 | 3.44 | 1.21 | ||

| S64 | The ability to enjoy sexual activity | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S68 | To be appreciated as a whole person is important to my sexual expression | V | 2–5 | 4.18 | 1.00 | ||

| S69 | To be intimate with a particular person, with or without actual intercourse | V | 3–5 | 4.29 | 0.66 | ||

| S70 | To explore my sexuality with a particular person | M | 1–5 | 3.59 | 1.30 | ||

| S71 | Touching, kissing, and being attentive to the other person | V | 2–5 | 4.40 | 0.79 | ||

| Determinants of sexual desire | S1 | A feeling I have when I get a certain look, touch, or conversation from someone I find attractive | M | 1–5 | 3.74 | 1.02 | 3.87 (0.26) |

| S19 | Finding another person attractive and physically appealing | M | 1–5 | 3.81 | 0.96 | ||

| S29 | How comfortable in my body or how attractive I feel | V | 2–5 | 4.03 | 0.80 | ||

| S30 | How I relate to someone in terms of making eye contact, touching them, how I speak to them and the words I use | V | 3–5 | 4.22 | 0.69 | ||

| S65 | The atmosphere and surrounds | M | 2–5 | 3.55 | 0.84 | ||

| Sexual expression | S27 | Having intercourse | M | 1–5 | 3.62 | 1.07 | 3.42 (0.35) |

| S38 | Massage | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S45 | Nakedness | M | 1–5 | 3.66 | 1.03 | ||

| S47 | Oral sex | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.40 | ||

| S57 | Sensual body movements | M | 1–5 | 3.85 | 0.98 | ||

| S73 | Visual stimulation | M | 1–5 | 3.51 | 1.08 | ||

| S75 | Watching my partner in the shower | S | 1–5 | 2.88 | 1.25 | ||

| Determinants of sexual expression | S8 | It is important that my partner is clean when expecting me to respond | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.44 | 3.22 (0.64) |

| S23 | Gender is important in terms of sexual expression | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.65 | ||

| S26 | Going along because of the other person's needs at the time | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.10 | ||

| S28 | Health and wellbeing | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.91 | ||

| S31 | I tend to “fly solo” | S | 1–5 | 2.11 | 1.52 | ||

| S42 | Moral and privacy standards (eg, there is a time and a place to express your sexuality that is acceptable in our society) | S | 1–5 | 2.70 | 1.32 | ||

| S58 | Sexual orientation and how you express or act upon your sexual feelings | M | 1–5 | 3.14 | 1.56 | ||

| S66 | Through behavior and the way in which I present myself particularly in the company of the opposite sex | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.11 | ||

| S67 | Time and opportunity for sex | M | 2–5 | 3.96 | 0.93 | ||

| Barriers to intimacy | S10 | Energy levels | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 0.92 | 2.84 (0.63) |

| S15 | Fear of being hurt | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.45 | ||

| S16 | Fear of forming a new relationship | S | 1–4 | 2.11 | 1.12 | ||

| S41 | Mood or mental state | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 1.44 | ||

| Sexual urges | S12 | Enjoying erotic print and film media alone or with a partner | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.31 | 2.72 (0.31) |

| S14 | Fantasizing and thoughts | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.30 | ||

| S20 | Flirting | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.14 | ||

| S33 | It is an underlying driving force that never goes away | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.55 | ||

| S37 | Manual orgasm | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.39 | ||

| S72 | Urge for physical release of body fluids | S | 1–5 | 2.62 | 1.47 | ||

| S74 | Voyeurism | S | 1–5 | 2.25 | 1.31 | ||

| Barriers to sexual expression | S3 | Alcohol or drug use prevents me from expressing my sexuality | N | 1–5 | 1.55 | 1.31 | 2.36 (0.55) |

| S32 | Illness or pain interferes with sexual expression | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.67 | ||

| S35 | Lack of opportunity | S | 1–5 | 2.33 | 1.35 | ||

| S36 | Lack of suitable company | N | 1–5 | 1.70 | 1.23 | ||

| S39 | Medications | N | 1–4 | 1.88 | 1.18 | ||

| S40 | Mismatched libido with my partner | N | 1–5 | 1.92 | 1.38 | ||

| S46 | Not feeling the urge | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.28 | ||

| S48 | Partner’s illness and medical treatment | S | 1–5 | 2.85 | 1.72 | ||

| S49 | Partner’s lack of interest or tiredness | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.51 | ||

| S52 | Physical disabilities | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.57 | ||

| S62 | Sometimes I do not want to express my sexuality | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.38 | ||

| Cluster . | ID . | Statement . | Importance rating . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating . | Range . | Mean . | SD . | Cluster mean (SD) . | |||

| Partner compatibility | S2 | A sense of freedom of expression and appreciation of our differences | V | 2–5 | 4.00 | 0.83 | 4.37 (0.24) |

| S6 | Being able to communicate openly | V | 3–5 | 4.62 | 0.56 | ||

| S9 | Compatibility with each other | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.14 | ||

| S17 | Feeling cared for and valued | V | 2–5 | 4.37 | 0.83 | ||

| S18 | Feeling safe | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.87 | ||

| S21 | Freedom to be myself | V | 2–5 | 4.22 | 0.93 | ||

| S22 | Friendship/positive regard for you and your partner | V | 3–5 | 4.48 | 0.70 | ||

| S54 | Respect is important | V | 3–5 | 4.70 | 0.54 | ||

| S60 | Someone whose mind and personality are attractive | V | 3–5 | 4.55 | 0.57 | ||

| Intimacy and pleasure | S4 | An emotional response to a physical need of touch | V | 3–5 | 4.11 | 0.64 | 4.22 (0.31) |

| S5 | Anticipation for when we share those special moments together | V | 3–5 | 4.07 | 0.72 | ||

| S7 | Being able to hold and be held | V | 3–5 | 4.59 | 0.57 | ||

| S11 | Enjoying each other’s bodies | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S13 | Expression of desire or interest | M | 3–5 | 3.92 | 0.82 | ||

| S24 | General petting and intimacy | V | 2–5 | 4.11 | 0.80 | ||

| S25 | Giving and receiving pleasure | V | 3–5 | 4.37 | 0.68 | ||

| S34 | Knowing that my partner finds me attractive | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 0.95 | ||

| S43 | Mutual attraction and satisfaction | V | 3–5 | 4.51 | 0.64 | ||

| S44 | Mutual trust and understanding | V | 3–5 | 4.81 | 0.55 | ||

| S50 | Partner’s smile | V | 1–5 | 4.14 | 1.13 | ||

| S51 | Physical contact of some sort, hugging, holding hands, kissing | V | 2–5 | 4.55 | 0.80 | ||

| S53 | Playful activities leading up to being intimate (eg, pats and hugs throughout the day) | V | 3–5 | 4.25 | 0.81 | ||

| S55 | Romance | V | 3–5 | 4.14 | 0.71 | ||

| S56 | Sensuality | V | 3–5 | 4.18 | 0.68 | ||

| S59 | Sharing the things that are the most personal part of you | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S61 | Something that brings emotional satisfaction | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.73 | ||

| S63 | Speaking softly to each other is an important part of intimacy | M | 1–5 | 3.44 | 1.21 | ||

| S64 | The ability to enjoy sexual activity | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S68 | To be appreciated as a whole person is important to my sexual expression | V | 2–5 | 4.18 | 1.00 | ||

| S69 | To be intimate with a particular person, with or without actual intercourse | V | 3–5 | 4.29 | 0.66 | ||

| S70 | To explore my sexuality with a particular person | M | 1–5 | 3.59 | 1.30 | ||

| S71 | Touching, kissing, and being attentive to the other person | V | 2–5 | 4.40 | 0.79 | ||

| Determinants of sexual desire | S1 | A feeling I have when I get a certain look, touch, or conversation from someone I find attractive | M | 1–5 | 3.74 | 1.02 | 3.87 (0.26) |

| S19 | Finding another person attractive and physically appealing | M | 1–5 | 3.81 | 0.96 | ||

| S29 | How comfortable in my body or how attractive I feel | V | 2–5 | 4.03 | 0.80 | ||

| S30 | How I relate to someone in terms of making eye contact, touching them, how I speak to them and the words I use | V | 3–5 | 4.22 | 0.69 | ||

| S65 | The atmosphere and surrounds | M | 2–5 | 3.55 | 0.84 | ||

| Sexual expression | S27 | Having intercourse | M | 1–5 | 3.62 | 1.07 | 3.42 (0.35) |

| S38 | Massage | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S45 | Nakedness | M | 1–5 | 3.66 | 1.03 | ||

| S47 | Oral sex | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.40 | ||

| S57 | Sensual body movements | M | 1–5 | 3.85 | 0.98 | ||

| S73 | Visual stimulation | M | 1–5 | 3.51 | 1.08 | ||

| S75 | Watching my partner in the shower | S | 1–5 | 2.88 | 1.25 | ||

| Determinants of sexual expression | S8 | It is important that my partner is clean when expecting me to respond | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.44 | 3.22 (0.64) |

| S23 | Gender is important in terms of sexual expression | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.65 | ||

| S26 | Going along because of the other person's needs at the time | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.10 | ||

| S28 | Health and wellbeing | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.91 | ||

| S31 | I tend to “fly solo” | S | 1–5 | 2.11 | 1.52 | ||

| S42 | Moral and privacy standards (eg, there is a time and a place to express your sexuality that is acceptable in our society) | S | 1–5 | 2.70 | 1.32 | ||

| S58 | Sexual orientation and how you express or act upon your sexual feelings | M | 1–5 | 3.14 | 1.56 | ||

| S66 | Through behavior and the way in which I present myself particularly in the company of the opposite sex | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.11 | ||

| S67 | Time and opportunity for sex | M | 2–5 | 3.96 | 0.93 | ||

| Barriers to intimacy | S10 | Energy levels | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 0.92 | 2.84 (0.63) |

| S15 | Fear of being hurt | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.45 | ||

| S16 | Fear of forming a new relationship | S | 1–4 | 2.11 | 1.12 | ||

| S41 | Mood or mental state | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 1.44 | ||

| Sexual urges | S12 | Enjoying erotic print and film media alone or with a partner | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.31 | 2.72 (0.31) |

| S14 | Fantasizing and thoughts | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.30 | ||

| S20 | Flirting | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.14 | ||

| S33 | It is an underlying driving force that never goes away | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.55 | ||

| S37 | Manual orgasm | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.39 | ||

| S72 | Urge for physical release of body fluids | S | 1–5 | 2.62 | 1.47 | ||

| S74 | Voyeurism | S | 1–5 | 2.25 | 1.31 | ||

| Barriers to sexual expression | S3 | Alcohol or drug use prevents me from expressing my sexuality | N | 1–5 | 1.55 | 1.31 | 2.36 (0.55) |

| S32 | Illness or pain interferes with sexual expression | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.67 | ||

| S35 | Lack of opportunity | S | 1–5 | 2.33 | 1.35 | ||

| S36 | Lack of suitable company | N | 1–5 | 1.70 | 1.23 | ||

| S39 | Medications | N | 1–4 | 1.88 | 1.18 | ||

| S40 | Mismatched libido with my partner | N | 1–5 | 1.92 | 1.38 | ||

| S46 | Not feeling the urge | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.28 | ||

| S48 | Partner’s illness and medical treatment | S | 1–5 | 2.85 | 1.72 | ||

| S49 | Partner’s lack of interest or tiredness | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.51 | ||

| S52 | Physical disabilities | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.57 | ||

| S62 | Sometimes I do not want to express my sexuality | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.38 | ||

M = moderately important; N = not at all important; S = slightly important; V = very important.

Distribution of clustered statements and mean importance scores across identified clusters

| Cluster . | ID . | Statement . | Importance rating . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating . | Range . | Mean . | SD . | Cluster mean (SD) . | |||

| Partner compatibility | S2 | A sense of freedom of expression and appreciation of our differences | V | 2–5 | 4.00 | 0.83 | 4.37 (0.24) |

| S6 | Being able to communicate openly | V | 3–5 | 4.62 | 0.56 | ||

| S9 | Compatibility with each other | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.14 | ||

| S17 | Feeling cared for and valued | V | 2–5 | 4.37 | 0.83 | ||

| S18 | Feeling safe | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.87 | ||

| S21 | Freedom to be myself | V | 2–5 | 4.22 | 0.93 | ||

| S22 | Friendship/positive regard for you and your partner | V | 3–5 | 4.48 | 0.70 | ||

| S54 | Respect is important | V | 3–5 | 4.70 | 0.54 | ||

| S60 | Someone whose mind and personality are attractive | V | 3–5 | 4.55 | 0.57 | ||

| Intimacy and pleasure | S4 | An emotional response to a physical need of touch | V | 3–5 | 4.11 | 0.64 | 4.22 (0.31) |

| S5 | Anticipation for when we share those special moments together | V | 3–5 | 4.07 | 0.72 | ||

| S7 | Being able to hold and be held | V | 3–5 | 4.59 | 0.57 | ||

| S11 | Enjoying each other’s bodies | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S13 | Expression of desire or interest | M | 3–5 | 3.92 | 0.82 | ||

| S24 | General petting and intimacy | V | 2–5 | 4.11 | 0.80 | ||

| S25 | Giving and receiving pleasure | V | 3–5 | 4.37 | 0.68 | ||

| S34 | Knowing that my partner finds me attractive | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 0.95 | ||

| S43 | Mutual attraction and satisfaction | V | 3–5 | 4.51 | 0.64 | ||

| S44 | Mutual trust and understanding | V | 3–5 | 4.81 | 0.55 | ||

| S50 | Partner’s smile | V | 1–5 | 4.14 | 1.13 | ||

| S51 | Physical contact of some sort, hugging, holding hands, kissing | V | 2–5 | 4.55 | 0.80 | ||

| S53 | Playful activities leading up to being intimate (eg, pats and hugs throughout the day) | V | 3–5 | 4.25 | 0.81 | ||

| S55 | Romance | V | 3–5 | 4.14 | 0.71 | ||

| S56 | Sensuality | V | 3–5 | 4.18 | 0.68 | ||

| S59 | Sharing the things that are the most personal part of you | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S61 | Something that brings emotional satisfaction | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.73 | ||

| S63 | Speaking softly to each other is an important part of intimacy | M | 1–5 | 3.44 | 1.21 | ||

| S64 | The ability to enjoy sexual activity | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S68 | To be appreciated as a whole person is important to my sexual expression | V | 2–5 | 4.18 | 1.00 | ||

| S69 | To be intimate with a particular person, with or without actual intercourse | V | 3–5 | 4.29 | 0.66 | ||

| S70 | To explore my sexuality with a particular person | M | 1–5 | 3.59 | 1.30 | ||

| S71 | Touching, kissing, and being attentive to the other person | V | 2–5 | 4.40 | 0.79 | ||

| Determinants of sexual desire | S1 | A feeling I have when I get a certain look, touch, or conversation from someone I find attractive | M | 1–5 | 3.74 | 1.02 | 3.87 (0.26) |

| S19 | Finding another person attractive and physically appealing | M | 1–5 | 3.81 | 0.96 | ||

| S29 | How comfortable in my body or how attractive I feel | V | 2–5 | 4.03 | 0.80 | ||

| S30 | How I relate to someone in terms of making eye contact, touching them, how I speak to them and the words I use | V | 3–5 | 4.22 | 0.69 | ||

| S65 | The atmosphere and surrounds | M | 2–5 | 3.55 | 0.84 | ||

| Sexual expression | S27 | Having intercourse | M | 1–5 | 3.62 | 1.07 | 3.42 (0.35) |

| S38 | Massage | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S45 | Nakedness | M | 1–5 | 3.66 | 1.03 | ||

| S47 | Oral sex | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.40 | ||

| S57 | Sensual body movements | M | 1–5 | 3.85 | 0.98 | ||

| S73 | Visual stimulation | M | 1–5 | 3.51 | 1.08 | ||

| S75 | Watching my partner in the shower | S | 1–5 | 2.88 | 1.25 | ||

| Determinants of sexual expression | S8 | It is important that my partner is clean when expecting me to respond | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.44 | 3.22 (0.64) |

| S23 | Gender is important in terms of sexual expression | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.65 | ||

| S26 | Going along because of the other person's needs at the time | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.10 | ||

| S28 | Health and wellbeing | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.91 | ||

| S31 | I tend to “fly solo” | S | 1–5 | 2.11 | 1.52 | ||

| S42 | Moral and privacy standards (eg, there is a time and a place to express your sexuality that is acceptable in our society) | S | 1–5 | 2.70 | 1.32 | ||

| S58 | Sexual orientation and how you express or act upon your sexual feelings | M | 1–5 | 3.14 | 1.56 | ||

| S66 | Through behavior and the way in which I present myself particularly in the company of the opposite sex | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.11 | ||

| S67 | Time and opportunity for sex | M | 2–5 | 3.96 | 0.93 | ||

| Barriers to intimacy | S10 | Energy levels | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 0.92 | 2.84 (0.63) |

| S15 | Fear of being hurt | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.45 | ||

| S16 | Fear of forming a new relationship | S | 1–4 | 2.11 | 1.12 | ||

| S41 | Mood or mental state | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 1.44 | ||

| Sexual urges | S12 | Enjoying erotic print and film media alone or with a partner | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.31 | 2.72 (0.31) |

| S14 | Fantasizing and thoughts | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.30 | ||

| S20 | Flirting | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.14 | ||

| S33 | It is an underlying driving force that never goes away | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.55 | ||

| S37 | Manual orgasm | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.39 | ||

| S72 | Urge for physical release of body fluids | S | 1–5 | 2.62 | 1.47 | ||

| S74 | Voyeurism | S | 1–5 | 2.25 | 1.31 | ||

| Barriers to sexual expression | S3 | Alcohol or drug use prevents me from expressing my sexuality | N | 1–5 | 1.55 | 1.31 | 2.36 (0.55) |

| S32 | Illness or pain interferes with sexual expression | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.67 | ||

| S35 | Lack of opportunity | S | 1–5 | 2.33 | 1.35 | ||

| S36 | Lack of suitable company | N | 1–5 | 1.70 | 1.23 | ||

| S39 | Medications | N | 1–4 | 1.88 | 1.18 | ||

| S40 | Mismatched libido with my partner | N | 1–5 | 1.92 | 1.38 | ||

| S46 | Not feeling the urge | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.28 | ||

| S48 | Partner’s illness and medical treatment | S | 1–5 | 2.85 | 1.72 | ||

| S49 | Partner’s lack of interest or tiredness | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.51 | ||

| S52 | Physical disabilities | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.57 | ||

| S62 | Sometimes I do not want to express my sexuality | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.38 | ||

| Cluster . | ID . | Statement . | Importance rating . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating . | Range . | Mean . | SD . | Cluster mean (SD) . | |||

| Partner compatibility | S2 | A sense of freedom of expression and appreciation of our differences | V | 2–5 | 4.00 | 0.83 | 4.37 (0.24) |

| S6 | Being able to communicate openly | V | 3–5 | 4.62 | 0.56 | ||

| S9 | Compatibility with each other | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.14 | ||

| S17 | Feeling cared for and valued | V | 2–5 | 4.37 | 0.83 | ||

| S18 | Feeling safe | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.87 | ||

| S21 | Freedom to be myself | V | 2–5 | 4.22 | 0.93 | ||

| S22 | Friendship/positive regard for you and your partner | V | 3–5 | 4.48 | 0.70 | ||

| S54 | Respect is important | V | 3–5 | 4.70 | 0.54 | ||

| S60 | Someone whose mind and personality are attractive | V | 3–5 | 4.55 | 0.57 | ||

| Intimacy and pleasure | S4 | An emotional response to a physical need of touch | V | 3–5 | 4.11 | 0.64 | 4.22 (0.31) |

| S5 | Anticipation for when we share those special moments together | V | 3–5 | 4.07 | 0.72 | ||

| S7 | Being able to hold and be held | V | 3–5 | 4.59 | 0.57 | ||

| S11 | Enjoying each other’s bodies | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S13 | Expression of desire or interest | M | 3–5 | 3.92 | 0.82 | ||

| S24 | General petting and intimacy | V | 2–5 | 4.11 | 0.80 | ||

| S25 | Giving and receiving pleasure | V | 3–5 | 4.37 | 0.68 | ||

| S34 | Knowing that my partner finds me attractive | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 0.95 | ||

| S43 | Mutual attraction and satisfaction | V | 3–5 | 4.51 | 0.64 | ||

| S44 | Mutual trust and understanding | V | 3–5 | 4.81 | 0.55 | ||

| S50 | Partner’s smile | V | 1–5 | 4.14 | 1.13 | ||

| S51 | Physical contact of some sort, hugging, holding hands, kissing | V | 2–5 | 4.55 | 0.80 | ||

| S53 | Playful activities leading up to being intimate (eg, pats and hugs throughout the day) | V | 3–5 | 4.25 | 0.81 | ||

| S55 | Romance | V | 3–5 | 4.14 | 0.71 | ||

| S56 | Sensuality | V | 3–5 | 4.18 | 0.68 | ||

| S59 | Sharing the things that are the most personal part of you | V | 1–5 | 4.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S61 | Something that brings emotional satisfaction | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.73 | ||

| S63 | Speaking softly to each other is an important part of intimacy | M | 1–5 | 3.44 | 1.21 | ||

| S64 | The ability to enjoy sexual activity | V | 3–5 | 4.44 | 0.64 | ||

| S68 | To be appreciated as a whole person is important to my sexual expression | V | 2–5 | 4.18 | 1.00 | ||

| S69 | To be intimate with a particular person, with or without actual intercourse | V | 3–5 | 4.29 | 0.66 | ||

| S70 | To explore my sexuality with a particular person | M | 1–5 | 3.59 | 1.30 | ||

| S71 | Touching, kissing, and being attentive to the other person | V | 2–5 | 4.40 | 0.79 | ||

| Determinants of sexual desire | S1 | A feeling I have when I get a certain look, touch, or conversation from someone I find attractive | M | 1–5 | 3.74 | 1.02 | 3.87 (0.26) |

| S19 | Finding another person attractive and physically appealing | M | 1–5 | 3.81 | 0.96 | ||

| S29 | How comfortable in my body or how attractive I feel | V | 2–5 | 4.03 | 0.80 | ||

| S30 | How I relate to someone in terms of making eye contact, touching them, how I speak to them and the words I use | V | 3–5 | 4.22 | 0.69 | ||

| S65 | The atmosphere and surrounds | M | 2–5 | 3.55 | 0.84 | ||

| Sexual expression | S27 | Having intercourse | M | 1–5 | 3.62 | 1.07 | 3.42 (0.35) |

| S38 | Massage | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.07 | ||

| S45 | Nakedness | M | 1–5 | 3.66 | 1.03 | ||

| S47 | Oral sex | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.40 | ||

| S57 | Sensual body movements | M | 1–5 | 3.85 | 0.98 | ||

| S73 | Visual stimulation | M | 1–5 | 3.51 | 1.08 | ||

| S75 | Watching my partner in the shower | S | 1–5 | 2.88 | 1.25 | ||

| Determinants of sexual expression | S8 | It is important that my partner is clean when expecting me to respond | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.44 | 3.22 (0.64) |

| S23 | Gender is important in terms of sexual expression | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.65 | ||

| S26 | Going along because of the other person's needs at the time | M | 1–5 | 3.07 | 1.10 | ||

| S28 | Health and wellbeing | V | 2–5 | 4.33 | 0.91 | ||

| S31 | I tend to “fly solo” | S | 1–5 | 2.11 | 1.52 | ||

| S42 | Moral and privacy standards (eg, there is a time and a place to express your sexuality that is acceptable in our society) | S | 1–5 | 2.70 | 1.32 | ||

| S58 | Sexual orientation and how you express or act upon your sexual feelings | M | 1–5 | 3.14 | 1.56 | ||

| S66 | Through behavior and the way in which I present myself particularly in the company of the opposite sex | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.11 | ||

| S67 | Time and opportunity for sex | M | 2–5 | 3.96 | 0.93 | ||

| Barriers to intimacy | S10 | Energy levels | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 0.92 | 2.84 (0.63) |

| S15 | Fear of being hurt | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.45 | ||

| S16 | Fear of forming a new relationship | S | 1–4 | 2.11 | 1.12 | ||

| S41 | Mood or mental state | M | 1–5 | 3.37 | 1.44 | ||

| Sexual urges | S12 | Enjoying erotic print and film media alone or with a partner | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.31 | 2.72 (0.31) |

| S14 | Fantasizing and thoughts | M | 1–5 | 3.18 | 1.30 | ||

| S20 | Flirting | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.14 | ||

| S33 | It is an underlying driving force that never goes away | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.55 | ||

| S37 | Manual orgasm | S | 1–5 | 2.77 | 1.39 | ||

| S72 | Urge for physical release of body fluids | S | 1–5 | 2.62 | 1.47 | ||

| S74 | Voyeurism | S | 1–5 | 2.25 | 1.31 | ||

| Barriers to sexual expression | S3 | Alcohol or drug use prevents me from expressing my sexuality | N | 1–5 | 1.55 | 1.31 | 2.36 (0.55) |

| S32 | Illness or pain interferes with sexual expression | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.67 | ||

| S35 | Lack of opportunity | S | 1–5 | 2.33 | 1.35 | ||

| S36 | Lack of suitable company | N | 1–5 | 1.70 | 1.23 | ||

| S39 | Medications | N | 1–4 | 1.88 | 1.18 | ||

| S40 | Mismatched libido with my partner | N | 1–5 | 1.92 | 1.38 | ||

| S46 | Not feeling the urge | S | 1–5 | 2.51 | 1.28 | ||

| S48 | Partner’s illness and medical treatment | S | 1–5 | 2.85 | 1.72 | ||

| S49 | Partner’s lack of interest or tiredness | M | 1–5 | 3.29 | 1.51 | ||

| S52 | Physical disabilities | S | 1–5 | 2.44 | 1.57 | ||

| S62 | Sometimes I do not want to express my sexuality | S | 1–5 | 2.92 | 1.38 | ||

M = moderately important; N = not at all important; S = slightly important; V = very important.

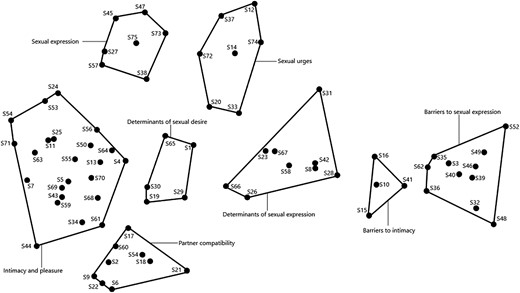

Hierarchical cluster analysis produced a shortlist of cluster solutions that contained 7, 8, or 9 clusters for examination. Solutions with more than 9 clusters were discarded because they contained conceptually redundant clusters or included at least 1 cluster with only 1 item. Solutions with fewer than 7 clusters were discarded due to a lack of conceptually cohesive themes in some of the clusters. After examination of shortlisted solutions, the 7-cluster solution was also rejected because it contained a cluster that was not clearly interpretable. Consequently, the preferred cluster solution was identified as the 8-cluster solution because it contained no single-item clusters and had no conceptually overlapping clusters, and statements in each cluster formed cohesive, interpretable themes. A cluster map of the 8-cluster solution can be found in Figure 1 . The 8 clusters were named based on identified themes within each cluster: partner compatibility, intimacy and pleasure, determinants of sexual desire, sexual expression, determinants of sexual expression, barriers to intimacy, sexual urges, and barriers to sexual expression.

Map of 8 thematic clusters identified by group concept mapping.

Cluster Definitions

Sexual Expression

Seven statements formed the sexual expression cluster and reflected the different ways individuals may express their sexuality. This cluster encompassed statements that referred more specifically to physical acts or partnered activities as a way of engaging with and expressing sexuality. Statements captured in this cluster included “[other than sexual intercourse, I also express my sexuality through] visual stimulation” and “[to me, sexuality means] having intercourse.”

Sexual Urges

Seven statements formed the sexual urges cluster and reflected the urges that underlie sexual expressions. This cluster included statements relating to sexual desires, physical sexual urges, and other forms of sexual expression. Statements captured in this cluster included “[other than sexual intercourse, I also express my sexuality through] fantasizing” and “[sexuality] is an underlying driving force that never goes away.”

Intimacy and Pleasure

The intimacy and pleasure cluster encompassed 23 statements and was the largest cluster of statements. Eighteen of these statements reflected the sexual experiences related to how an individual is intimate with others, and experiences of pleasure. Five statements within the intimacy and pleasure cluster reflected determinants that influence how an individual is intimate with others and their experiences of pleasure. Alternative solutions failed to separate this cluster into smaller clusters while retaining meaning in other clusters. The experiences captured in the intimacy and pleasure cluster encompassed both the ability and the need for affectionate, intimate, and some sexual behaviors, whereas statements that reflected determinants that influence sexual expression emphasized the quality of the intimate relationship and partner engagements, mutual trust, and mutual attraction. Statements captured in this cluster included “to be appreciated as a whole person is important to my sexual expression,” “[to me, sexuality and intimacy] are giving and receiving pleasure,” and “intimacy is sharing the things that are the most personal part of you.”

Partner Compatibility

Nine statements were grouped together to form the partner compatibility cluster. Statements in this cluster encompassed the determinants associated with feeling comfortable with and cared for by a romantic partner. It also included statements about being able to communicate with a partner and the acceptance and mutual respect between partners. Statements captured in this cluster included “feeling cared for and valued [is important to me in terms of sexual expression]” and “a sense of freedom of expression and appreciation of our differences [is important to me in terms of sexual expression].”

Determinants of Sexual Desire

Five statements were grouped together to form the determinants of sexual desire cluster, and they referred to factors associated with the experience or onset of sexual desire. Statements captured in this cluster included “[I can express my sexuality through] how I relate to someone in terms of making eye contact, touching them, how I speak to them and the words I use” and “finding another person attractive and physically appealing [is important to me in terms of how I express my sexuality].”

Determinants of Sexual Expression

Nine statements were included in the determinants of sexual expression cluster. These referred to the factors that influenced the way people thought about and expressed themselves sexually, their sexual standards, and the ways they engaged with others sexually. Statements captured in this cluster included “it is important that my partner is clean when expecting me to respond” and “moral and privacy standards [can prevent me from expressing my sexuality].”

Barriers to Intimacy

Four statements were grouped together to form the barriers to intimacy cluster. This cluster related to determinants that impinged upon an individual’s willingness to engage with another person on an intimate and/or sexual level. Statements captured in this cluster included “a fear of being hurt [prevents me from being able to express my sexuality]” and “energy levels [can prevent me from being able to express my sexuality].”

Barriers to Sexual Expression

Eleven statements were grouped together to form the barriers to sexual expression cluster. These related primarily to physical, medical, or social factors that act as barriers to sexual expression. Statements captured in this cluster included “illness or pain interferes with sexual expression” and “sometimes I do not want to express my sexuality.”

Cluster Proximity

Clusters were arranged on the bivariate point map as determined by MDS and HCA (see Figure 1). Clusters that were most proximal to each other included the partner compatibility and intimacy and pleasure clusters, the sexual expression and sexual urges clusters, and the barriers to intimacy and barriers to sexual expression clusters. Proximal clusters could be seen to share similar ideas. For example, the item “freedom to be myself” from the partner compatibility cluster is similar to, yet still distinct from, the item “to be appreciated as a whole person is important to my sexual expression” in the intimacy and pleasure cluster. Clusters that were located farther apart on the cluster map were less likely to share similar themes. For example, the barriers to sexual expression cluster had few similarities with the partner compatibility cluster, and these two clusters were found on opposite sides of the cluster map.

Cluster Importance

An overall importance rating for each cluster was produced by using the mean importance rating scores of all statements included within the cluster (Table 2). The partner compatibility and intimacy and pleasure clusters produced average importance ratings above 4 (very important); the determinants of sexual desire, sexual expressions, and determinants of sexual expression clusters produced average importance ratings above 3 (moderately important); and the barriers to intimacy, sexual urges, and barriers to sexual expression clusters produced average importance ratings above 2 (slightly important) overall by participants. No clusters produced average importance ratings equal to 5 (extremely important) or below 2 (not important at all).

Thematic Analysis of Perceived Change to Sexual Experience with Increasing Age

Twenty-two participants stated that they had experienced changes to their sexuality over time, and 7 participants stated that they had not experienced any changes to their sexuality over time. Most participants that reported no change to their sexuality were women (71% women), and all participants that reported no change to their sexuality were in midlife. Eleven participants chose to not provide a response to this question. The changes discussed by participants encompassed 7 themes: changes to perspective, changes to relationship dynamics, environmental changes, behavior changes, physical changes, changes to sexual interest/desire, and increased sexual enjoyment. A summary of themes identified by age cohort and gender can be found in Table 3 .

Sum totals of described changes to the experience of sexuality with age across gender and age cohorts

| Theme . | Midlife (M/F) . | Later life (M/F) . | Total (M/F) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No change | 7 (2/5) | 0 (0/0) | 7 (2/5) |

| Changes to perspective | 7 (3/4) | 15 (8/7) | 22 (11/11) |

| Changes to relationship dynamics | 7 (2/5) | 7 (4/3) | 14 (6/8) |

| Environmental changes | 3 (0/3) | 3 (1/2) | 6 (1/5) |

| Behavioral changes | 2 (0/2) | 11 (5/6) | 13 (5/8) |

| Physical changes | 4 (1/3) | 12 (8/4) | 16 (9/7) |

| Changes to interest/desire | 7 (2/5) | 9 (4/5) | 16 (6/10) |

| Increased enjoyment | 2 (0/2) | 7 (2/5) | 9 (2/7) |

| Theme . | Midlife (M/F) . | Later life (M/F) . | Total (M/F) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No change | 7 (2/5) | 0 (0/0) | 7 (2/5) |

| Changes to perspective | 7 (3/4) | 15 (8/7) | 22 (11/11) |

| Changes to relationship dynamics | 7 (2/5) | 7 (4/3) | 14 (6/8) |

| Environmental changes | 3 (0/3) | 3 (1/2) | 6 (1/5) |

| Behavioral changes | 2 (0/2) | 11 (5/6) | 13 (5/8) |

| Physical changes | 4 (1/3) | 12 (8/4) | 16 (9/7) |

| Changes to interest/desire | 7 (2/5) | 9 (4/5) | 16 (6/10) |

| Increased enjoyment | 2 (0/2) | 7 (2/5) | 9 (2/7) |

F = female; M = male.

Sum totals of described changes to the experience of sexuality with age across gender and age cohorts

| Theme . | Midlife (M/F) . | Later life (M/F) . | Total (M/F) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No change | 7 (2/5) | 0 (0/0) | 7 (2/5) |

| Changes to perspective | 7 (3/4) | 15 (8/7) | 22 (11/11) |