-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lasse Folke Henriksen, Leonard Seabrooke, Kevin L Young, Intellectual rivalry in American economics: intergenerational social cohesion and the rise of the Chicago school, Socio-Economic Review, Volume 20, Issue 3, July 2022, Pages 989–1013, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwac024

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Neoliberal economics has reshaped societies. How did this doctrine ascend? While existing explanations emphasize a variety of factors, one neglected aspect is intellectual rivalry within the US economics profession. Neoliberalism had to attain prestige against the grain of the intelligentsia prior to becoming a force to organize political power. Using qualitative and quantitative evidence, we examine key rivals in US economics from 1960 to 1985: the Chicago School of Economics, neoliberal pioneers and the ‘Charles River Group’ (Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), the mainstream Keynesian stronghold. We identify socialization mechanisms from historical accounts, which suggest forms of social cohesion between elite professors and their students. We measure social cohesion and network structure from salient relations within and between generations, using a new a dataset focused on elite economics professors and their graduate students. What differentiated the Chicago School from Charles River was its fostering of social cohesion and its effective transmission of value orientations across generations.

1. Introduction

The ascendance of neoliberal economic thought is one of the most wide-reaching intellectual trends of the last half-century. From a relatively marginal and radical position in the 1950s and 1960s, neoliberal economics became the prevailing operational ideology not just of the economics discipline but of much economic policy by the mid-1980s (Kogut and MacPherson, 2011). The common sense of economic theory and policy was profoundly transformed to favor market competition as a solution to socio-economic problems and the governing of societies (Mudge, 2018). Numerous accounts have documented the rise of neoliberal thought within economics, within policy making and within intellectual environments at large (Fourcade-Gourinchas and Babb, 2002; Backhouse, 2005; Gibbon and Henriksen, 2012; Reay, 2012; Mandelkern, 2021). Our account focuses on the neoliberal rise and related decline of Keynesian economics in the US by focusing on the intellectual rivalry between the two elite communities contending to define mainstream economics.

Historical accounts have emphasized a wide variety of factors contributing to the rise of neoliberal economics in the US, ranging from the role of particular think tanks and foundations (Mirowski and Plehwe, 2009; Hirschman and Berman, 2014), orchestration within the business community (Kotz, 2015; Van Horn, 2018), the center-left’s embrace of economic reforms for white collar and business constituencies (Mudge, 2018), intergovernmental organizations (Kentikelenis and Babb, 2019) and changes to the global economic environment (Slobodian, 2018). Most of these accounts suggest selection pressures in the environment as the key explanation for the emergence of neoliberal economics. Some refer to direct resource dependencies in the Chicago School’s institution-building process, while others point to more diffuse factors such as shifting demand for ideas favoring neoliberal economic solutions.

An alternate strand of scholarship on the rise of neoliberal economics has pointed to more strategic considerations related to the professional environment when accounting for the rise of the Chicago School. These historical accounts suggest that the founding fathers at Chicago promoted and enforced a strong collective culture around a professoriate throughout the 1960s (Van Overtveldt, 2007; Emmet, 2011). From this view, Chicago professors were aware that to challenge the dominance of Keynesian ideas, they would have to work not just on producing alternative economic ideas but also organize a cadre of scholars that could disseminate them. Existing accounts do not pay sufficient attention to how Chicago organized vis-à-vis the core community of what was then mainstream economics: varieties of Keynesianism.1 We undertake such a systematic comparison, focusing on the two most prominent elite communities vying for dominance in US economics during the 1960s and 1970s. The first is the Chicago-based Chicago School of Economics. The second is the community of economics scholars based in Cambridge, MA, that included both Harvard and MIT, and sometimes referred to as the ‘Charles River Group’.

The term ‘Charles River Group’ of economists refers colloquially to economists at both Harvard and MIT that represented the mainstream Keynesian–Neoclassical synthesis of its heyday during the 1960s and early 1970s. The term has been used in a variety of historical depictions of the era, especially with reference to governmental policy advising by economists. The ‘Charles River approach’ was promoted by social scientists, mainly economists, from MIT and Harvard, directly influenced Kennedy and had a distinct set of messages (Packenham, 1973, pp. 61–62). Reference to the ‘Charles River school of economics’ has also been made in retrospective histories of the 1960s (Karaagac, 2002).2 We use this term here for convenience, to refer to the collection of economists at both Harvard and MIT, which represented the group of established intellectuals that Chicago had to surmount in order to ascend.

While many sophisticated accounts exist on the drivers behind the rise of neoliberal economics, the puzzle remains how such a rapid shift from Keynesian to neoliberal ideas could occur. Previous scholarship has demonstrated how changing socio-economic and political conditions—notably the oil crises, stagflation and the rise of Reagan and Thatcher—contributed to this development. We argue that to understand the timing and speed of this transition, it is not sufficient to only account for selection pressures in the institutional environment in which economics operates. Prior to the development of an institutional environment conducive to neoliberal policies, intellectual development to foment the neoliberal revolution was already taking place, among academics. While the existence of important neoliberal ideas has been recognized in extant work, what we argue is that the Chicago School tradition possessed a social dynamic that outcompeted their entrenched rivals among the more Keynesian mainstream of American economics. Chicagoans were not only intellectually vociferous, but they also fostered strong solidarity and tight intergenerational cohesion.

To make sense of the neoliberal ascent, we need to understand that the intellectual advocates for what became neoliberalism had to professionally compete with a mainstream wedded to an opposing set of ideas. While the institutional environment in favor of neoliberal ideas surged from the mid-1970 onwards, the social networks of competing groups within American economics started to change in favor of the neoliberals as early as 1965. The resilience of neoliberal ideas, in terms of their embedding in an elite intellectual community, was on the rise a decade before key institutional shifts. This, in turn, compounded the simultaneous fracturing of the Keynesian elite community as the resilience of their ideas was increasingly tested. We agree that the institutional shifts emphasized by existing scholarship are key to explaining the ascent of neoliberal ideas, but these shifts arrived when Chicagoans were primed and ready to exploit and cement a new common sense (Forder, 2014).3 Neoliberals were not only able to compete in this context but they were also able to endure, intergenerationally. The two contending groups’ preparedness to adapt to institutional shifts was shaped by the underlying social networks between professors and students. A significant historical divergence in these social networks suggests they played a role in speeding up ideational change, making neoliberal ideas more readily matched to an emerging institutional context than their Keynesian counterparts.

2. Theoretical motivation

Our study builds on previous work in the sociology of science and empirical historical work on intergroup dynamics. To identify community structures tied to schools of thought, scholars have studied collaboration and citation networks at the level of entire scientific disciplines (Price, 1965; Crane, 1972; Lievrouw, 1989), and linked such communities to scientific paradigms (Small, 1980; McMahan and McFarland, 2021). Moody (2004), in particular, stresses network cohesion as the key structural property of community strength.

Within intellectual communities, social cohesion occurs through shared ideas and interpersonal relationships (Friedkin, 1978; Moody, 2004), which can be maintained across generations. Randall Collins’ work on the ‘sociology of philosophies’ points to how the driving force behind intellectual networks is ‘divergent factions that make it go’, and that intergenerational social cohesion between teachers and pupils is especially important in propelling groups forward (Collins, 1989, pp. 112, 115). It is the personal relationships among professors and students that affirm what is considered an intellectual innovation and what should be esteemed (Collins, 1989, 1998; Polillo, 2020). Such ‘academic familism’ fosters intellectual momentum (Bandelj, 2019). Specifically, Collins suggests that cohesion within intellectual movements can be studied through citation networks, vertical (teacher–pupil) and horizontal networks (generational peers), and organizational memberships (Collins, 1989, p. 115). Ties within these networks should include ‘both friends and foes’ where the groups involved have physical presence (Collins, 2004, pp. 191–192). Intellectual rivalries in these networks are common since key groups ‘depend tacitly upon each other, and structure each other’s direction of thought’ as they compete for the same ‘attention space’ (Collins, 1998, p. 790, 2004, p. 194).

We draw on Collins’ work on intellectual networks to explain how the Chicago School of Economics fostered cohesion across scholarly generations in the 1960s and 1970s. We contrast the Chicago School to their nearest rivals in elite US economics, the Charles River Group composed of Harvard and MIT. Compared to Chicago, this group, especially Harvard, produced less social cohesion within and across generations. The Chicago School’s fostering of cohesion over generations allowed it to become an entrenched group that could effectively promote its professional, political and economic interests and alliances.

To conduct this comparison, we locate an elite set of professors who were associated with, respectively, the Chicago School and the Charles River Group environments, and then trace the hundreds of graduate students that they trained and socialized. As Collins (1998, p. 78) reminds us, to ‘say that the community of creative intellectuals is small is really to say that the networks are focused at a few peaks’. To understand the relationship between the elite professoriate and the broader intellectual network, we study the intellectual networks among the professors, and between the professors and their students. As such, we investigate the role of doctoral training programs and the mentorship of doctoral dissertation supervisors, as these act as critical staging environments affecting social cohesion across generations, enabling the promotion and reproduction of particular intellectual traditions (Collins, 1989, p. 115). We assemble data on the intellectual networks of the professors and students from 1960 to 1985, a period of heightened intellectual struggle. We show that group reproduction is stronger when social cohesion within and in-between generations is actively fostered.

We contribute to scholarship in the sociology of science, including that on the rise of particular economic ideas (Van Gunten et al., 2016; Polillo, 2020), by linking changes in the level of social cohesion among elite scientists and their students to the timing of when certain ideas become resilient enough to be perceived as mainstream scientific knowledge. We also contribute to the scholarship on the history of economics that combines qualitative and quantitative methods (Cherrier and Svorenčík, 2018), including the use of prosopographic methods to trace groups of economists and their shared biographical characteristics (Svorenčík, 2018; Rossier, 2020). Such methods can identify ‘hidden hierarchies’ that are obscured if one focuses only on the known leading stars (Svorenčík, 2014, p. 110). We show empirically that a peculiar divergence in how elite intellectual rivals organized socially played a significant role in how the Chicago School could rapidly become mainstream (Helgadóttir, 2021), after having been considered radical outsiders for decades.

3. The context for rivalry among elite American economists

The US economics profession is characterized by high levels of hierarchy and centrality in decision making, which is protected by elite status and prestige (Fourcade et al., 2015). This hierarchy affords elite professors an extraordinary amount of control over knowledge production and what is considered prestigious work. This context means that toppling an entrenched group is no easy feat. While Chicago was clearly an elite department among US economics departments, with Harvard and MIT, its self-identity reflected an underdog status that contributed to their social cohesiveness (Reder, 1982).4

Relative to Harvard, in particular, the professoriate associated with Chicago was less prestigious and much less integrated into the economic policy establishment at the onset of our observation period. Keynesian economics dominated textbooks, classroom discussion and policymaking forums in the 1950s and 1960s, in addition to policy (Frazer, 1988, pp. 436–437). Buchanan (1987, p. 131) remarked that ‘…by the middle of the 1940s, economists almost everywhere had become ‘Keynesians’ in their conceptualization of the macroeconomy. They had quickly learned to look at their world through the Keynesian window.’ As Samuelson noted in 1946, ‘Keynesian analysis has begun to filter down into the elementary textbooks; and, as everybody knows, once an idea gets into these, however bad it may be, it becomes practically immortal’ (Samuelson, 1946, p. 189).

The 1960s were a high point for the professoriate associated with the Charles River Group, especially for those identifying as Keynesian economists. There was strong confidence in the Keynesian-Neoclassical synthesis from the Kennedy and Johnson administrations at the time (see Frazer, 1988, pp. 436–437). The ‘Charles River approach’ to development economics, from MIT and Harvard economists, directly influenced Kennedy and had a distinct set of messages (see Packenham, 1973, pp. 61–62). By the early 1960s overtures by the US Federal government were seen as evidence that ‘the American Government, a generation after the General Theory, had accepted the Keynesian revolution’ (Schlesinger, Jr, 1964 , p. 769). Scholars at Harvard and MIT were ensconced within the architecture of US economic policymaking.

In this environment, there was social stigma attached to being associated with the body of knowledge coming out of the Chicago School. Duke University refused to carry Milton Friedman’s books, for example (Skousen, 2005, p. 73). As another former Chicago student wrote, ‘The phrase Chicago Economics was often uttered with the same contempt that commonly characterized unsavory ethnic and religious epithets’ (Manne, 2005, pp. 311–312). In his memoirs, Milton Friedman describes the social environment outside Chicago as inhospitable:

Those of us who were deeply concerned about the danger to freedom and prosperity from the growth of government, from the triumph of the welfare state and Keynesian ideas, were a small beleaguered minority regarded as eccentrics by the great majority of our fellow intellectuals. (Friedman, 1982, p. vi)

Not only Friedman but also other scholars were questioned about their Chicago School affiliations. Exchanges in the archival record reveal a real sensitivity to labels such as the Chicago School, because it was seen as ideological. Important for our intergenerational approach is the fact that the particular costs of a Chicago reputation followed recent PhD graduates around at the time (Bronfenbrenner, 1962, p. 72). What Chicagoans later referred to as ‘the dark ages of Keynesian despotism’ was eventually overturned to a considerable degree (Johnson 2003, p. 170). The professoriate associated with the Chicago School required particular forms of socialization to challenge the Charles River Group’s dominance.

4. What was so special about the Chicago school of economics?

The importance of the University of Chicago to the advance of neoliberal thought is well established in the extensive literature on the history and sociology of economics (van Overtveldt, 2007; van Horn et al., 2011). This literature has been concerned with the external as well as the internal conditions for success. Amadae (2003) and Van Horn (2007) view the Chicago School as ‘rationalizing agents’, responding to the emerging institutional conditions of a new postwar democratic capitalism. Several of these accounts stress the instrumental role that Chicago had in building a coherent intellectual project around neoliberalism, as well as enrolling a transnational network based on a perception of marginalized outsider status—the Mont Pèlerin Society in particular—to promote their doctrine (Van Horn and Mirowski, 2010; Mudge, 2018, pp. 60–61, 241–242; Van Horn, 2018).

There are several existing qualitative accounts of a unique organizational culture at Chicago fostered in the 1950s and 1960s (Bronfenbrenner, 1962, p. 72; Hammond, 1999). In the early 1960s, Miller asserted that ‘Chicagoans do in fact form an interconnected group with a set of common attitudes and interest which distinguishes them from the rest of the economics profession’ (Miller, 1962, p. 64). Van Overtveldt (2007) points to a distinct organizational culture centered on: a strong work ethic; a strong belief in economics as a true, positive science; academic excellence as the only criterion for advancement; a fierce debating culture designed to cultivate disciplined thinkers around a doctrine; and the University of Chicago’s physical isolation from other elite universities (see also Shils, 1991; Fand, 1999, p. 12). It is worth elaborating on intensive training, debate within a doctrine and selective isolation as key socialization mechanisms that encouraged vertical and horizontal cohesion within the Chicago School.

First, on intensive training, the Chicago Economics Department had a very strong commitment to graduate student training and support (Patinkin, 1981, pp. 10–11) and focused intensely on its graduate student cohorts (Rossi, 1989, p. 290). Early on in his tenure, Friedman made a series of critical changes to the graduate curriculum and to PhD examination processes, and remained a pivotal figure in graduate training (see Reder, 1982, p. 10). All Chicago graduate students were steeped in price theory to forge a common foundation of knowledge. Emmet (2011) discusses how graduate students were trained in the core courses by star professors and then placed into a battery of intensive workshops. The system, emerging in the mid-1950 and fully developed by the mid-1960s, developed a collective sense of belonging among the students. The business school was also kept intentionally close to social sciences, most notably to economics (cf. Fourcade and Khurana 2017).

Second, on debate within a doctrine, Van Horn and Mirowski (2009) point to the role played by institutional entrepreneurs such as Aaron Director, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman in developing collective doctrine development projects such as the ‘Free Market Project’ and the ‘Antitrust Project’ as a way of working together toward a common doctrine. Within the bounds of the doctrine intense debating was strongly encouraged. Weekly seminars were a unique contribution to the field at the time (McCloskey, 1992, p. 19) and regarded as extremely ‘bloodthirsty’ (see Van Overtveldt, 2007, p. 39–41). Faculty and graduate students met in professors’ homes to vote on the validity of theoretical discussions and applications to economic policy (Medema, 2009, p. 104).

Third, on selective isolation, those in the Chicago School worked ‘more or less independently’ of the ‘intellectual academic setting elsewhere’ (Fand, 1999, p. 11). This was in part due to geography, being isolated from the large and prestigious incumbent universities, and also even within the city of Chicago itself (on the poor South Side) (Peck, 2010, pp. 84–85, 107–108). But isolation was also encouraged, with selective ties to allies in academia and industry. By one account the economics department ‘provided a relatively insular and protected atmosphere similar to that of a seminary’ (Fand, 1999, p. 12). At the same time, the department developed ties to Chicago’s financial sector provided them with alternative intellectual sparring partners with a common free market purpose. The combination of these various unique conditions culminated in both faculty and students being a unique, disciplined and coherent group with an ‘anti-Keynesian professional identity’ married to rational expectations and a belief in the positive capacities of the free market (Van Gunten, 2015, p. 334).

Established accounts of the Charles River Group suggest that intensive training, debate within a doctrinal culture and selective isolation were less intensively fostered. On intensive training, Harvard had the most prestigious graduate training program in the country in the 1950s and 1960s. The courses were embedded in the dominant Keynesian thinking of the time. Integration with the postwar policymaking establishment meant that professors were often occupying key government positions and advising roles. While this enhanced the reputation of the department in the short term, it did introduce costs to the graduate curriculum. Correspondingly, some of the star professors, such as Galbraith, had little time for graduate student supervision and did not supervise many graduate students. While graduate students were exposed to the Keynesian cutting edge in economics, there was not a robust culture of debate within a doctrine, and this was not a prominent feature of professor–student interactions (See Gintis in Colander et al., 2004; Parker, 2005).

During the 1950s and 1960s, MIT focused on ascending in the ranks for graduate training prestige by maintaining intensive training within a relatively smaller cohort (Cherrier, 2014, p. 85). MIT produced fewer graduate students than its rivals until the 1970s, with figures like Solow and Dornbusch fostering the early generation of students, followed by Kindleberger (Svorenčík, 2014, pp. 113, 120). MIT worked to inculcate a distinctive brand of economics that emphasized macroeconomics, growth models, mathematical training and the application of simple models to real-world problems. Debate was encouraged within this broader focus rather than a concentrated doctrine. While MIT prided itself on focusing on real-world economic problems as part of its curricula, by the late 1960s, MIT ‘was perceived as too theoretically oriented and remote from real world issues’ (Fischer, 2004, p. 249).

On selective isolation, faculty at both Harvard and MIT were thoroughly involved in the world of policymaking, from the Council of Economic Advisors to presidential advisory roles and special government committee assignments. The Kennedy and Johnson administrations featured a great degree of Harvard faculty involvement, in particular. Unlike Chicago, due to its isolation, Harvard and MIT were institutionally shaken up by the civil rights and anti-war protests of the late 1960s. At Harvard, the late 1960s protests further fomented divisions already brewing among faculty, putting them in different camps based on alignment with anti-war protesters (Galbraith, 1981; Parker, 2005). This led to prominent disagreements among key Harvard Faculty, such as between Galbraith and Gershenkron (Davidoff, 2002, pp. 306–309). MIT economics was under political strain when it was disclosed that they did extensive work for the Central Intelligence Agency and the US defense department. This led not only to social agitation and protests (occupation of buildings where the economics department was located, suspension of classes) but also to MIT failing to recruit several targeted faculty at the time (Cherrier, 2014, pp. 38–39). The rise of the New Left also saw demands for radical political economy courses. At both Harvard and MIT, the Union of Radical Political Economics had a presence and connected the protest movements to curricular reform, as well as the politicization of tenure and promotion cases (Katzner, 2011). Given these external pressures, graduate students in the Charles River Group were enmeshed in larger ideological struggles in which their professors did not coordinate to offer a unified position.

Informed by this qualitative evidence, we ask if institutionally embedded socialization mechanisms contributed to cohesion in network structures in the Chicago School and the Charles River Group.

5. Data and network measures

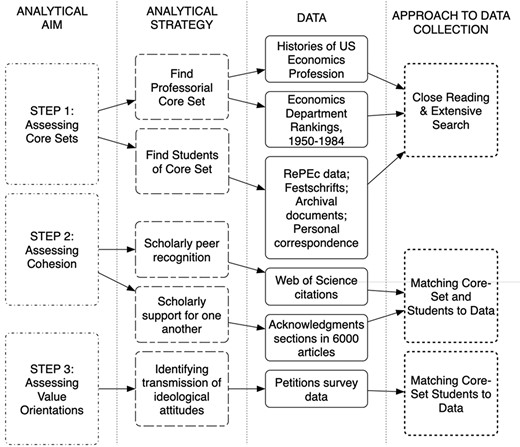

Our data and analysis proceeds in three empirical steps, and uses a wide range of data sources and methods, as summarized in Figure 1 below. Empirical step 1 establishes how we identified the core-set professors and their students. Empirical step 2 analyzes network cohesion within and between the two rival groups. We focus on network measures associated with group cohesion. We construct the network measures drawing on bibliometric data. Empirical step 3 compares value orientations among the professors and students using petition data. The logic here is that if socialization mechanisms in intensive training, doctrine and debate and selective isolation are present they should be reflected through scholarly peer recognition in citations, in peer support through acknowledgements, and in enduring value orientations associated with policy doctrines. We track the historical evolution of these measures during a period of intellectual rivalry in US economics.

5.1 Sample population

Our initial analytical task was to establish two populations, which are by no means taken for granted or already established. First, the prominent scholarly proponents associated with the Chicago School and the Charles River Group were located. Second, a population of their doctoral students was identified to establish the intellectual lineage from the professors. Although our archival work extended beyond these years, we focus on the period from 1960 to 1985, when rivalry among these groups was most intense. It is clear that during this period Chicago challenged the place of two key departments which shuffled for elite supremacy in US economics, Harvard and MIT. As communities of professors and their students, the Chicagoans and the Charles River Group sought to occupy similar attention space, vied for elite status and informed each other’s work.

We document the logic behind this matching, which entailed a wide range of historical data on university and department prestige, as well as the perceived caliber of graduate training.5 Choosing Harvard and MIT as a contrast to Chicago is also appealing because they form a geographically proximate community of scholars, and the professors we select from each were both part of a similar intellectual milieu at the time and recognized each other as peers involved in the production of next generation scholars. This minimizes variation in propinquity, which is strongly associated with network formation and intellectual production (Jaffe et al., 1993). Harvard and MIT were known for being strongholds of the Keynesian–Neoclassical synthesis and institutional economics, theoretical paradigms that the Chicagoans were explicitly attacking.

To obtain our cast of prominent scholarly proponents, we collected and coded 100 different texts that described either the neoliberal transition in economics or the professional lives of economists linked to the intellectual environments of interest. We call these ‘memoire’ texts, as they are usually backward-looking retrospectives on professional developments within the field, most often centered around one individual economist. These include book chapters, published articles commemorating a career, festschrifts and many published interviews. By coding each of the economists that was mentioned in these texts, we generated a large network of mutual regard, wherein we could establish lists of key individuals who should be included in our study. Thus, in contrast to an approach that identifies common biographical attributes of individuals (cf. Svorenčík, 2018), we opted to utilize the relational structure of narratives—provided by economists themselves—that identify individual’s mutual regard for one another, thus allowing us to assess which economists showed regard and esteem toward each other (Brennan and Pettit, 2004).

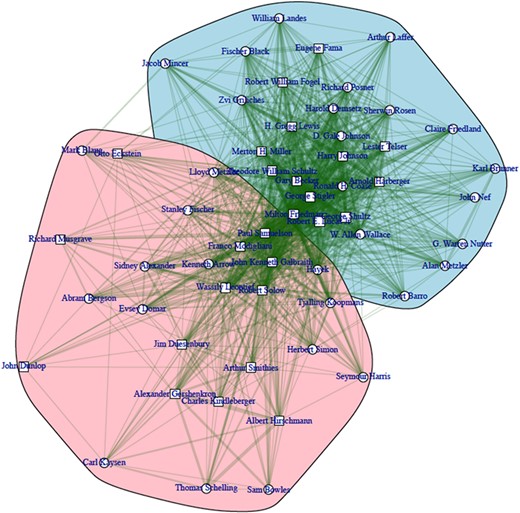

We coded our 100 texts in a large matrix, locating memoir texts on one axis and individual economist names on the other. Of the 543 economists found in the memoires, we located 142 that were mentioned at least three times. We then conducted professional profiles on each to ascertain inclusion criteria regarding whether the economist was professionally active or retired in the period under study and whether or not they had moved through Chicago, Harvard and MIT in their careers, a process that left 57 economists and their ties to one another through memoire texts. From a two-mode bipartite network of memoire texts and economists, we generated a one-mode network consisting of only economists connected through their co-presence in memoire texts, illustrated in Figure 2 below. The resultant network provides important information on three aspects. First, it establishes a list of key economists which we can then sample from. Second, it allows us to check whether economists selected are close to the core of this network, or dispersed throughout. Third, it allows us to visualize the relational space of intellectual rivalry within the network as an emergent structure, through community detection. Figure 2 provides the output of our network following community detection, using the Louvain community detection algorithm (previously used in Seabrooke and Young, 2017). It shows two distinct groups: the Chicago School (blue, at top) and the Charles River Group (red, at bottom).6

Community detection of core-set economists from memoire network.

| Chicago . | Charles River . |

|---|---|

| Becker, G. S. (Chicago) | Duesenberry, J.S. (Harvard) |

| Fama, E. F. (Chicago) | Dunlop, J.T. (Harvard) |

| Fogel, R. W. (Chicago) | Eckstein, O. (Harvard) |

| Friedman, M. (Chicago) | Galbraith, J.K. (Harvard) |

| Harberger, A. (Chicago) | Gerschenkron, A. (Harvard) |

| Johnson, H.G. (Chicago) | Hirschman, A. (Harvard) |

| Lewis, H.G. (Chicago) | Leontief, W. (Harvard) |

| Lucas, R. E. Jr. (Chicago) | Musgrave, R. A. (Harvard) |

| Miller, M. H. (Chicago) | Smithies, A. (Harvard) |

| Shultz, G. (Chicago) | Kindleberger, C. P. (MIT) |

| Schultz, T. W. (Chicago) | Modigliani, F. (MIT) |

| Stigler, G. J. (Chicago) | Samuelson: A. (MIT) |

| Telser, L. G. (Chicago) | Solow, R. M. (MIT) |

| Students found = 276 | Students found = 308 |

| Chicago . | Charles River . |

|---|---|

| Becker, G. S. (Chicago) | Duesenberry, J.S. (Harvard) |

| Fama, E. F. (Chicago) | Dunlop, J.T. (Harvard) |

| Fogel, R. W. (Chicago) | Eckstein, O. (Harvard) |

| Friedman, M. (Chicago) | Galbraith, J.K. (Harvard) |

| Harberger, A. (Chicago) | Gerschenkron, A. (Harvard) |

| Johnson, H.G. (Chicago) | Hirschman, A. (Harvard) |

| Lewis, H.G. (Chicago) | Leontief, W. (Harvard) |

| Lucas, R. E. Jr. (Chicago) | Musgrave, R. A. (Harvard) |

| Miller, M. H. (Chicago) | Smithies, A. (Harvard) |

| Shultz, G. (Chicago) | Kindleberger, C. P. (MIT) |

| Schultz, T. W. (Chicago) | Modigliani, F. (MIT) |

| Stigler, G. J. (Chicago) | Samuelson: A. (MIT) |

| Telser, L. G. (Chicago) | Solow, R. M. (MIT) |

| Students found = 276 | Students found = 308 |

| Chicago . | Charles River . |

|---|---|

| Becker, G. S. (Chicago) | Duesenberry, J.S. (Harvard) |

| Fama, E. F. (Chicago) | Dunlop, J.T. (Harvard) |

| Fogel, R. W. (Chicago) | Eckstein, O. (Harvard) |

| Friedman, M. (Chicago) | Galbraith, J.K. (Harvard) |

| Harberger, A. (Chicago) | Gerschenkron, A. (Harvard) |

| Johnson, H.G. (Chicago) | Hirschman, A. (Harvard) |

| Lewis, H.G. (Chicago) | Leontief, W. (Harvard) |

| Lucas, R. E. Jr. (Chicago) | Musgrave, R. A. (Harvard) |

| Miller, M. H. (Chicago) | Smithies, A. (Harvard) |

| Shultz, G. (Chicago) | Kindleberger, C. P. (MIT) |

| Schultz, T. W. (Chicago) | Modigliani, F. (MIT) |

| Stigler, G. J. (Chicago) | Samuelson: A. (MIT) |

| Telser, L. G. (Chicago) | Solow, R. M. (MIT) |

| Students found = 276 | Students found = 308 |

| Chicago . | Charles River . |

|---|---|

| Becker, G. S. (Chicago) | Duesenberry, J.S. (Harvard) |

| Fama, E. F. (Chicago) | Dunlop, J.T. (Harvard) |

| Fogel, R. W. (Chicago) | Eckstein, O. (Harvard) |

| Friedman, M. (Chicago) | Galbraith, J.K. (Harvard) |

| Harberger, A. (Chicago) | Gerschenkron, A. (Harvard) |

| Johnson, H.G. (Chicago) | Hirschman, A. (Harvard) |

| Lewis, H.G. (Chicago) | Leontief, W. (Harvard) |

| Lucas, R. E. Jr. (Chicago) | Musgrave, R. A. (Harvard) |

| Miller, M. H. (Chicago) | Smithies, A. (Harvard) |

| Shultz, G. (Chicago) | Kindleberger, C. P. (MIT) |

| Schultz, T. W. (Chicago) | Modigliani, F. (MIT) |

| Stigler, G. J. (Chicago) | Samuelson: A. (MIT) |

| Telser, L. G. (Chicago) | Solow, R. M. (MIT) |

| Students found = 276 | Students found = 308 |

Our prosopographic approach helps to establish key actors among elite economists during their day, rather than those that achieved recognition later in their careers. Our method is thus an alternative to using professional achievement or formal recognition, such as lists of Nobel Laureates or John Bates Clark medal holders, as has been done in other recent scholarship (see Bjork et al., 2014; Cherrier and Svorenčík, 2020).

Table 1 sets out the academic economists selected for our study, 13 from each group. All of these individuals contributed significantly to debates in US economics during the period of analysis and, importantly, are key figures within their respective intellectual tradition. These economists are marked with square rather than circular nodes in Figure 2 below. Existing scholarship usually emphasizes only a subset of the figures in our list, such as Friedman and Stigler (Van Horn et al.. 2011; Nik-Khah and Van Horn, 2016, p. 27). Our selection follows Collins’ view that it is not a particular individual who determines an intellectual network, but the ‘action of the entire network across generations that determines how much attention is paid to the ideas that are formulated at any particular point in it’ (Collins, 2004, p. 191).

To obtain student–supervisory lineages from 1960 to 1980 we followed a multi-faceted procedure. We consulted online repositories such as RepEc and Mathematics Genealogy, festschrifts, memorial dedications, transcripts of oral histories, student lists from department archives, extensive library searches for PhD theses and American Economics Association student member biographies. Historical archives were also consulted. These archival materials offered more than just additional raw data on supervisor–student name links, but were a rich source of contextual information about local institutional environments, professional strategies, and intergenerational relationships. For Chicago we found 276 students and for Charles River Group 308 students.

Despite this exhaustive and multi-faceted approach, we knew that our sample could potentially still have unknown selection bias issues. Some selection bias was certainly mitigated by the use of multiple sources, but we also pursued additional strategies involving the sampling of large student cohorts, as well as verifying that we had obtained a good sample based on the numbers of PhD graduates from each department.7

5.2 Measuring network cohesion

Having established 26 supervisors and 584 students from the rival groups, we set out to identify salient social ties within the population. The aim is to measure the respective level of group cohesion within and between supervisors and students of each group over time, using common network analytic measures. We focus on two types of social ties: citations and acknowledgements.

We collected data from Web of Science (WoS) on citations among the professors and their students, focusing on the citation network from 1960 to 1985. Citations are explicitly directed social acts that tie together papers and scholars through overlaps in substantive research interests (Hummon and Doreian, 1989). They also function as social rewards (Merton, 1968), as well as indicating where scientific ideas flow (Lynn, 2014). All the professors were identified in the data. 218 of the 276 total Chicago School students found were identified in the WoS data, and 240 of the total 308 Charles River Group students. We included articles, letters, and notes in our sample of citing works, matching the author names in our sample to citing works. We then extracted the reference lists from the citing work and matched author names in the reference lists to our sample names, combining string matching with manual quality checking and coding. This gave us a total of 426 unique authors, 404 of which were citing authors and 359 of which were cited authors. Self-citations were excluded. The resulting citation network consisted of all the professors from both groups and the matched students, and record all ties between the entire population of professor and students.

We focused on horizontal citation (within professors and students) as well as vertical citations (between professors and students) in the entire intellectual network. Within this network, we measured the relative share of in-group and out-group citations. Given that we observed all citations between professors and students in our population, the share of in-group citations out of the total number of citations a group send is our first indicator of in-group cohesion.

In addition to citations we also measured reciprocity and transitivity via scholarly support networks, detected through article acknowledgements. Social Exchange Theory suggests that people invest in those they perceive as friends and expect rewards from these investments (Emerson, 1976). In the context of friendship, ‘reciprocity entails responding to other people’s friendly gestures in kind’ (Block, 2015, p. 164). When exchange parties deem the balance between investment and returns satisfying, the friendship can continue. This logic extends to transitive triads where support is received indirectly from a friend of a friend (Newcomb, 1961). Acknowledgements are a common way of listing the peers that have been directly involved in providing feedback on a paper through participation in workshops or through direct dyadic involvement in the paper writing process. These directed ties indicate support in intellectual production. To gather acknowledgement ties, we took the publication records collected for the citation networks and coded the individuals listed in the acknowledgements section of these articles, when these were available. Treating each article author i and their acknowledged peers j as directed ties, we generated an ‘acknowledgement network’ from these data. From this data we measured levels of reciprocity and transitivity within the groups. 260 Chicago students and 302 Charles River students were identified and acknowledgement coded. All of the listed professors were identified and coded.

5.3 Assessing value orientations

We suggest that when strong socialization mechanisms are at play, being trained in the same school of thought produces similar value orientations which, in turn, is associated with tighter in-group network cohesion.8 We used data from Hedengren et al. (2010), who gathered 35 petitions and their signatories, from 1994 to 2009—a period in which Chicago School-style neoliberal economics was dominant in US economics (Reay, 2012)—and classified each petition according to left versus right value orientations. Importantly, these data not only have face validity but have been used in other scholarship and corroborated with other measures of ideology. Jelveh et al. (2018) have used these petition data and show that they accord well with two other sources of data: campaign contributions to either Republicans or Democrats on the one hand and, on the other hand, the kinds of language used in the publications of these authors. We found 5 professors and 64 of their students from the Charles River Group in the petition data, and 6 professors and 61 of students from the Chicago School. To compare value orientations, we focused on the relationship between professors and students, tracing the reproduction of value orientations across generations.

6. Results

6.1 In-group versus out-group citations

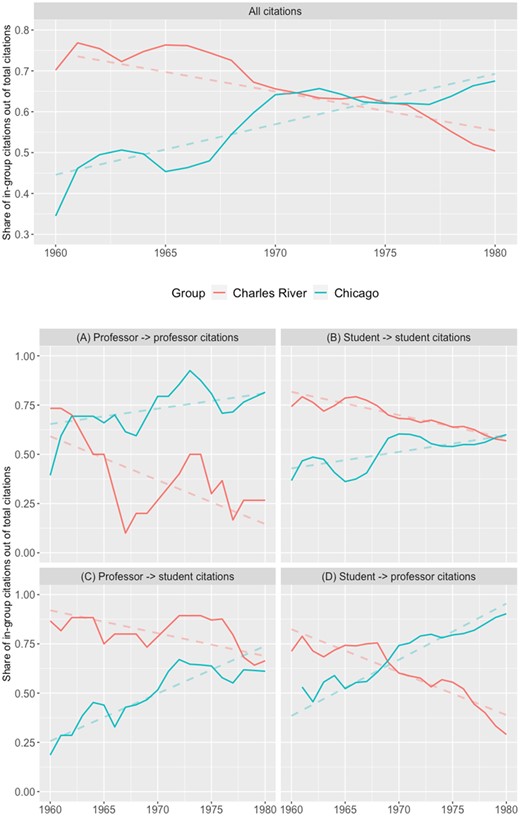

Figure 3 below presents the share of in-group ties in the citation network. The top panel illustrates the total share of in-group citations for each group. Note that in our analysis we observe only citations sent to the sampled professors and students. The share of in-group ties in the total sample of professors and students is relatively constant, hovering around 0.65 throughout the period. Breaking down the distribution by groups reveals a striking development. Whereas the share of in-group citations for the Charles River Group in the early 1960s—a period still associated with Keynesian dominance—was high and stable just above 0.7, this steeply decreased and dropped from 0.76 to 0.5 in the period 1965–1980. In contrast, the Chicago School group share of in-group ties increased from 0.35 to 0.67 during the same period. If we interpret this as one form of social cohesion, the two groups experienced a profound change in their overall levels of cohesion. The Charles River Group moved from being highly cohesive in the early 1960s (which also confirms that they were a cohesive intellectual collective despite their location at two different institutions within the same city) to being much less cohesive from the mid-1960s onwards. An important point to stress here is that the network of citations is made up of professors and students from two rival groups, which makes it likely that an out-group citation from i→j is a significant social act, suggesting that not only is a low share of in-group citations an indication of little social cohesion but also an indication of a strong orientation towards the out-group.

Subpanel (A) in Figure 3 displays the share of in-group citations among professors citing other professors. On this measure of cohesion within the professorial groups only, the Chicago School and Charles River Group professors steadily diverged with the Chicago School becoming more cohesive over time and the Charles River Group less so. At the outset of our observation period, the Charles River professors had a share of in-group citations around 0.75, a number which drops to below 0.25 by the late 1960s and remained well below .5 until 1980. The opposite is true for the Chicago School professors, which rose from 0.4 to 0.8 between 1960 and 1980.

Share of within group citations out of the total citations made by the group (dashed line is fitted using a simple linear regression).

Subpanel (B) shows the share of in-group citations among students citing other students, and illustrates an initially lower but ultimately growing social cohesion among the Chicago School students. Again, the opposite pattern repeats for the Charles River Group students, who in the early period were far more likely to cite their fellow students than in the later period. On this measure of cohesion within the junior generation the trend is clear but the difference toward the end of the observation period is less significant. Subpanel (C) illustrates a similar pattern but for professors citing students. Subpanel (D) shows the perhaps most noticable divergence of all: the share of in-group citations among the Charles River Group students were high during most of the 1960s but dropped from 0.75 to 0.27 from 1968 to 1980. Although the student to professor cohesion in the Charles River Group was very high at the outset, the Chicago School quickly outpaced them by the end of the 1960s. The Chicago students share of in-group citations when citing professors rose from 0.48 in 1962 to 0.9 in 1980. Given this analysis is of citations within the overall sample, subpanel (D) shows that after 1976 Charles River Group students were more likely to cite Chicago School professors than their own.

Focusing on panels (A) and (D) reveals that by the end of the period 68% of the citations sent by Chicago School faculty and students were addressed to scholars within the group, representing the apex of an ever-growing amount of social cohesion. At the same time the Charles River professors, while highly cohesive in the early 1960s, failed to reproduce their initial high levels of cohesion and by 1980 only 50% of citations were in-group. The fact that these trends occur before neoliberal economics truly takes off suggests that social cohesion is a one of several causes, and not just a consequence, of the neoliberal ascent.

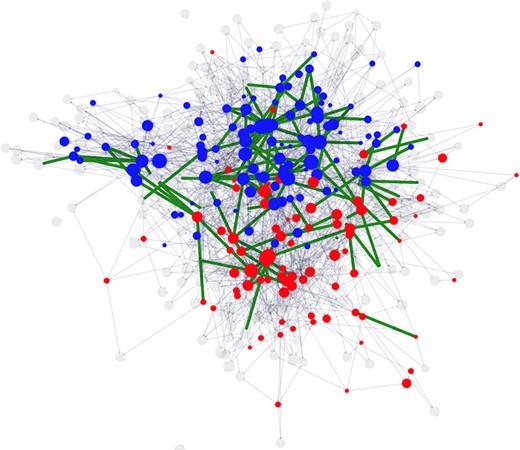

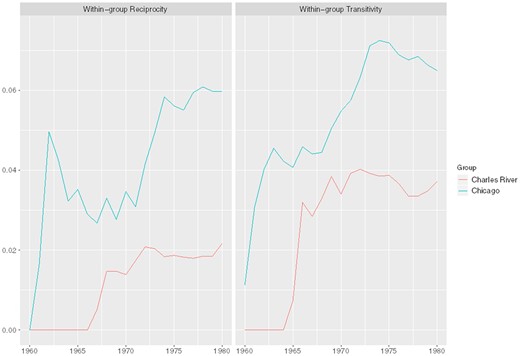

6.2 Reciprocity and transitivity in scholarly support

We also calculate reciprocity and transitivity, dividing the overall acknowledgement network into separate networks for the Chicago School and the Charles River Group. These generate unique networks cumulated over time from 1960 to 1980, including the professors and their students. Figure 4 presents our acknowledgement network. The green highlighted ties are acknowledgement ties that were reciprocated, which predominated among the blue (Chicago) nodes. Figure 5 presents the cumulated reciprocity and transitivity in the acknowledgement network, tracing the prevalence of each mechanism across the period.

Acknowledgement network, with Chicago in Blue and Charles River in Red.

Reciprocity and Transitivity in Acknowledgement Networks over time, 1960–1980.

In the leftmost panel of Figure 5, we observe cumulative reciprocity. In this case, it literally means ‘I thank you, you thank me’ dynamics within the journal publications of the time. The Chicago School was more frequently engaging in reciprocation, and their share of reciprocated ties increased over the period. In the beginning of the observation window, reciprocity was rare for both groups since a set of directed ties needs to be established before they can be reciprocated. For the Charles River Group, it took 6 years before a tie had been reciprocated, whereas for the Chicago School it took only 3 years. After their first reciprocation, the Charles River Group’s share of reciprocated ties remained just below 2%. For Chicago, the share was 0.05 in the early 1960s, then dropping to ca. 0.03 but in the early 1970s increasing to 0.06—three times higher than the Charles River Group—and staying there throughout the 1970s. This lends credence to the idea that mutual support was an important aspect in building social cohesion within the group. This is also exemplified in the different venues that Chicago School professors and students published in during this period, such as Journal of Political Economy—itself based at the University of Chicago—rather than in establishment journals such as the American Economic Review.

We also measured transitivity in acknowledgments, indicating closed triadic triplets where i→j→h→i. This is a measure of in-group mutual support in that it measures the extent of clique formation when it comes to helping one another with scientific production. As the right-hand panel of Figure 5 illustrates, the transitivity scores were significantly higher for the Chicago School economists than for their Charles River Group rivals. Transitivity increased for both groups over the observation period, with a peak in the mid-1970s for both groups—the Charles River Group at 0.04 and the Chicago School at 0.07.

The fact that the Chicago School had higher scores of both reciprocity and transitivity throughout this period, including in the 1960s before their triumph by the late 1970s, lends credence to the idea that these social cohesion dynamics played a causal role, rather than the acceptance of neoliberal economics in the US economics profession then making Chicagoans more cohesive.

6.3 Value orientations

Our analysis above stresses the differences in social cohesion, which we argue was important for neoliberal economists’ ascent. But social cohesion in the form of scholarly citations and acknowledgements does not necessarily entail a shared normative understanding about the future governance of the economy and instead could be driven by other factors, such as differences in methodological style. The collective intellectual project known as Chicago School was about changing the shared understanding of how economies are governed, which was at the heart of socialization processes at Chicago (Van Overtveldt, 2007; Mirowski and Plehwe, 2009). We propose that such value orientation was also an important feature in which the Chicago School stood out, with a higher degree of shared value among the professors, and between the professors and their students. This further strengthened social cohesion and produced a core doctrine that anchored the Chicago School as a collective agent in the academy and beyond (Mudge, 2018).

Figure 6, below, illustrates the result of mean left-right scores for all the economists in our sample that matched with the petitions data described above. Because Hedengren et al. (2010) and Jelveh et al. (2018) represent different scorings, we included both to see if any results would be sensitive to different scorings of left-right. We first generated simple counts using - and + values for the number of left or right-coded petitions a given economist signed. In Figure 6 below, we show the percentage score, whereby the left-right count is compared to the total number of petitions signed by a given economist. The error bars represent the standard deviation in each set of values, oriented about the mean. We observe these value orientations within the group much later than our other network data, which means that selection and survivor bias could skew our indicators. On the other hand, this is a powerful indicator of generational transfer of attitudes and its endurance into several decades after these economists received their training.

We compared each set of professors for the Chicago School and the Charles River Group, with their corresponding student group, to compare differences in value orientations across generations. To facilitate a baseline, we included the mean score for all economists who signed petitions in these data, which represents approximately 6000 economists, showing a slightly right-leaning orientation in general.

These results show the rightward orientation of the Chicago School professors, which conforms with our knowledge of this group. Notably, however, Chicago School students are relatively close in their orientation to their professors, across all scoring methods. The situation for Harvard and MIT is largely the opposite—these professors were more left-leaning in their petition-signing and this orientation did not translate over to their students as clearly, who gravitated closer to the center with a wide variation among the center indicating large differences in value orientations across generations.

One potential objection to this analysis is that students self-selected into different graduate programs based on their ideological proclivities. Yet, there are several important historical facts about how top graduate programs in economics operated that suggest that such selection effects are ameliorated. One is that economics during this period was seen as a highly technical subject, not dissimilar to how mainstream representations of the profession operate today. While there were important debates and dividing lines within economics from the postwar period to the 1970s, there was also a strong general confidence, related to the Keynesian–Neoclassical synthesis prevailing at the time, that technical fixes to economic problems were both possible and technocratic in nature (Fourcade-Gourinchas and Babb, 2002; Helgadóttir, 2021).

Second, top US economics departments clearly competed for graduate students and the terrain of competition was funding. Archival evidence from Harvard in the 1950s reveals how its economics department competed with Chicago and many other schools. While Harvard was more prestigious at the time, there was grave concern, from scholars like Galbraith, that Harvard would lose ground because of less generous funding packages. Many students were recruited into the MIT program though their interests in mathematics and physics, reflecting the cultural milieu of the school (Cherrier, 2014).

The third piece of evidence that supports the notion that ideological selection into economics programs was ameliorated has to do with biographical accounts of individuals’ ideology at the beginning of the program versus the end. Several prominent Chicago School graduates entered the program as leftists but did not leave the program that way (Stoller, 2018, p. 230). Accounts of the Chicago School environment in the 1950s suggest that most incoming students did not come to study for ideological motivations. According to Fand (1999), when it comes to the big questions of free enterprise and government planning, most students entered the program as social democrats.

7. Discussion

This article argues that the group identified with Chicago was more successful in reproducing social cohesion, even when the main rivals at Harvard and MIT were more initially prominent in the US economics profession. Cohesion in the Chicago group carried across generations, supporting the rise of neoliberal economics. Our analysis demonstrates that social cohesion in the Chicago School was quite limited during the early 1960s, when the Charles River Group was highly cohesive and mainstream. This relative distribution of social cohesion then flipped during the 1960s and 1970s. We posit that respective increases and declines in social cohesion was a central enabling factor in the tectonic epistemic shift from Keynesian dominance to the mainstreaming of neoliberal ideas during the 1970s and 1980s.

The Chicago School started from a position as self-perceived underdog, needing to build cohesion within their own peer group with heavily concerted action from key figures like Friedman and Stigler. Extant qualitative accounts stress how the Chicago School fostered socialization through intensive training, an organized system of debate within a doctrine, and selective isolation from other university environments while creating ties to the finance community. Chicago economists established close bonds with their students and a national reputation for their bloodlust and ambition. Over time the group became more cohesive both within its professoriate and in relations between professors and students. Value orientations of Chicago students also resembled their professors to a great extent. The label ‘Chicago School’, initially rejected as ideological slander, was later embraced as a marker of scientific rigor, conceptual clarity, and policy relevance. Textbooks were produced that propagated neoliberal economics and replicated myths about the failures of Keynesian economics (Forder, 2014). This is how neoliberal knowledge was supported in US economics, from which they entered into governments and corporations to promote economic reforms.

In contrast, the Charles River Group during the 1960 to 1985 period moved from a position of strong social cohesion and intellectual dominance to one where supportive relationships among the professoriate and between professors and students were less frequent. Compared to their Chicagoan peers, Harvard and MIT professors were more distant from their students and not known for maintaining ideological coherence. Their students increasingly cited Chicago professors more than their own and the value orientations of the students did not resemble their professors and were highly dispersed. Charles River Group professors and students also displayed far lower levels of reciprocal acknowledgement. While Keynesian economic models were modified, the lack of social cohesion to support their propagation is likely to have weakened their position in US economics. Importantly, these effects preceded the rise of the Chicago School. As such, they are not reducible to being merely a consequence of professional ascent but a cause of it.

While the rise of neoliberal economics is a causal process involving multiple factors, our evidence suggests that the Chicago School’s process of building a cohesive community of senior and junior scholars that could propagate the neoliberal gospel was not simply an effect of broader institutional developments: their cohesion was clearly on the rise in the 1960s when Keynesian thinking was still dominant. Our analysis contributes to, rather than competes with, existing accounts of the rise of neoliberal economics. Focusing attention on the group-level dynamics within the economics profession itself is valuable because of the importance of neoliberal ideas, which were generated and fostered within economics departments. The neoliberal turn was not only championed by politicians—but also forged in the academy—and its continued development was guided by leading figures who could propagate the simplicity and scientific character of neoliberal economic ideas (Reay, 2012; Mandelkern, 2021).

Our study of intellectual networks and how they foster social cohesion, within and across generations, provides new evidence on the rise of the Chicago School and contributes to our understanding of neoliberalism’s rise. Not only do we show that the Chicago School became more cohesive, but that their main rival lost cohesion. This ‘origin story’ is important to understand given the wide-reaching effects of the Chicago School. Research has shown how US economists’ opinions on issues like the diffusion of privatization converged among Chicago-trained economists in the 1990s (Macpherson, 2006, p. 196). Such convergence was important in propagating neoliberal economic reforms in Central and South American countries (Babb, 2001; Louçã and Ash, 2018), as well as in former communist Eastern European countries (Bockman and Eyal, 2002; Bandelj, 2008; Ban, 2016). Neoliberal economic thought has also been important in altering the policy direction of international organizations away from their original more Keynesian mandates (Ban, 2015; Kentikelenis and Seabrooke, 2017; Kentikelenis and Babb, 2019).

Such outcomes have a deeply social origin in how professors organized themselves and socialized their students to give to their intellectual network momentum. Studying how intellectual currents are sustained over generations is important in understanding what forms of science are valued over others, as well as how mentor–mentee networks affirm power asymmetries, including methodological and gender hierarchies within scholarly fields (Bandelj, 2019). In the context of an intellectual rivalry with the Charles River Group, the Chicago School of Economics developed institutionally embedded socialization mechanisms that supported high levels of social cohesion over generations. These social foundations are important in explaining the rise of neoliberal economics in the US, which then transformed the rest of the world.

Footnotes

Often contained within the neoclassical synthesis of its day, post-WWII US economics was, by the 1960s, dominated by a Keynesian orientation that is clearly distinguished from what later became to be known as neoliberalism, especially in its orientation around government intervention and the operation of markets. We say ‘varieties’ here because there were different levels to which Keynesian ideas were adopted, some more 'synthesized' with neoclassical ideas and models, and some more institutionalist than others.

In addition, in reviewing the fading of Keynesian dominance, Barraclough (1977) refers to ‘the bright boys along the Charles river’. ‘Charles River economists’ are also referred to colloquially by critiques of mainstream economists coming out of the area into the early 1990s (Clark, 1994).

Keynesians arguably did the same thing in the 1940s and the 1950s.

We justify the selection of Harvard and MIT specifically as rivals to Chicago drawing on range of historical prestige and training metrics (see Data and Network Measures below, and Supplementary Appendix A).

For details see Supplementary Appendix A.

Stanley Fischer is in the blue community, although it cannot be seen here. Further details are explained in Supplementary Appendix B. Full details and the methodological considerations can be found in Young et al., 2022.

These additional strategies are explained in Supplementary Appendix C.

Similarly, Ash et al. (2022) study the consequences of training judges through the Manne economics training program, which leads to stronger use of economics language in sentencing and harsher sentences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacob Lunding, Elizabeth Sullivan-Hasson, Eric Winkler, Elliot Jerry and Pamela Eisner, who all worked as research assistants on different parts of this project. We also acknowledge Jenny Andersson, Michael Ash, Cornel Ban, Jens Beckert, Bruce Carruthers, Carol Heim, Oddný Helgadóttir, Larry King, Elisa Klüger, Francisco Louçã, Doug McAdam, Mathieu Dufour, Elsa Massoc, David Stark, Mitchell Stevens and Marc Ventresca for their comments. Our special thanks also go to Thomas Ferguson for generative discussions about the project. Previous versions of this paper were presented at seminars at the Copenhagen Business School, Columbia University, Stanford University and at SASE conferences in 2016 and 2019. We are grateful to staff at the Hoover Institute archive, the JFK Memorial Library archives, the Harvard University Archives, the Duke University Rosenstein Library Archive, as well as staff in the Harvard and Chicago economics departments for assistance with historical PhD graduation data.

Funding

This project received funding from the Velux Foundation (#00021820-NICHE), the Institute for New Economic Thinking (#INO1500030) and the Independent Research Fund Denmark grant (#5052-001143-B).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material in the form of appendices are available here.