-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

André Pontes-Silva, Fibromyalgia: a new set of diagnostic criteria based on the biopsychosocial model, Rheumatology, Volume 63, Issue 8, August 2024, Pages 2037–2039, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keae074

Close - Share Icon Share

In the health field, the biopsychosocial model helps to capture people’s experience of chronic pain by affirming that biological, neuropsychological and socioenvironmental elements play a role in chronic pain–related processes [1]. These variables are embedded in the 1948 World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health, which states that health is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing—not merely the absence of disease [2].

The biopsychosocial model was then refined by the WHO with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health [1]; which addresses the complex interaction among health conditions, individuals and the environment in which individuals live, to understand health outcomes in terms of disability [2]. Namely, the biopsychosocial variables overcome the biomedical model, which focuses on purely biological mechanisms [1]. However, the biopsychosocial assessment model for patients with FM has been neglected throughout the historical process of diagnostic guidelines [3].

Historical development of FM diagnosis

In 1990, the ACR proposed the first official diagnostic criteria for FM: (i) widespread pain in combination with (ii) tenderness at 11 or more of the 18 specific tender point sites [4]. Furthermore, there must be a history of at least 3 months of generalized pain in some regions of the axial skeleton and in at least three of the four body quadrants (or, exceptionally, in two opposite ones concerning the two axes of body division) was required [4, 5]. This type of assessment characterizes a biomedical model for the diagnosis of FM [6], as it does not take into account the psychological and social factors suggested by the WHO [1].

In 2010, the ACR proposed a new version of the diagnostic criteria based solely on the use of two scales: the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and the Symptom Severity Scale (SSS), i.e. it does not require a tender point examination [7]. The WPI includes a list of 19 painful areas, and the SSS assesses the severity of fatigue, unrefreshed awakening and cognitive symptoms, as well as a checklist of 41 symptoms (irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue/tiredness, muscle weakness, RP, tinnitus, etc.). This type of assessment characterizes a biomedical model for the diagnosis of FM again, as it does not take into account the social factors suggested by the WHO [1].

In 2011, Wolfe et al. modified the 2010 ACR diagnostic criteria by replacing the physician’s estimate of somatic symptom severity with the sum of three specific self-reported symptoms, because the requirement for a physician’s examination was a major barrier to understanding the prevalence and characteristics of FM based on large epidemiologic or community-based studies [8]. However, only the 1990 and 2010 criteria have been officially endorsed by the ACR [4, 5]. The similarities between the 2010 and 2011 criteria [9] again highlight the biomedical model used.

In 2016, the criteria were updated again [4]: (i) widespread pain, defined as pain in at least four out of five body regions; (ii) symptoms have been present at a similar level for at least 3 months; (iii) WPI ≥7 and SSS score ≥5 (or WPI of 4–6 plus SSS score ≥9); and (iv) a diagnosis of FM does not exclude the presence of other clinically important conditions [4]. Although this updating initiative is important, it should be noted that patients continue to be evaluated according to the biomedical model [2]. In addition, the prevalence of FM appears to differ according to the diagnostic criteria used [4, 5]. Studies recruiting FM patients according to the 1990 ACR criteria reported higher mean WPI and SSS scores than studies recruiting patients according to the 2010/2011 ACR criteria [10]. However, international recommendations support the use of the 2016 ACR criteria, as the cognitive variables have been included in the assessment set [3, 6]—nevertheless, the social variables remain outside the analysis.

Biopsychosocial model: do we need to consider the three domains?

Although pain (biological component) is an important symptom in FM, other symptoms such as fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, mood disturbance and cognitive impairment (psychological component) are common and have an important impact on quality of life, emphasizing that this is a heterogeneous and complex condition [5].

Currently, it is known that social variables (social component) are associated with important outcomes in patients with FM [3], such as education level, ethnicity, employment status, monthly income, marital status, interpersonal relationship type, cohabitation, number of dependents, number of children, social support and knowledge of FM [3]. However, the diagnostic criteria established by the ACR and used in clinical research are still supported by the biomedical model, ignoring the WHO recommendations (i.e. a biopsychosocial model). Consequently, this has created a new gap in the scientific literature: the need for a new set of diagnostic criteria for FM based on the biopsychosocial model.

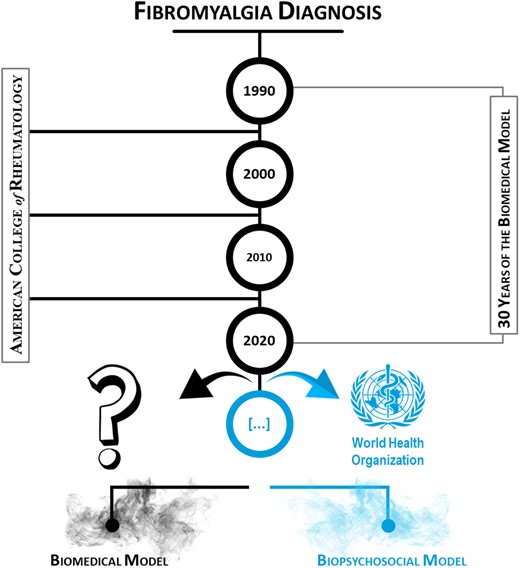

As such, knowing that the three components (bio, psycho and social) are associated with the quality of life of patients with FM, it is necessary to include all three in the set of diagnostic criteria. By projecting a timeline beginning in 1990, when the ACR published the first guidelines for diagnosing FM and jumping forward each decade, it is clear that the ACR has ignored the WHO recommendations for a biopsychosocial model of evaluation of FM for over 30 years (Fig. 1). Will this change by 2030?

Timeline of the biomedical model for the evaluation of FM patients

How may social variables be included in the set of diagnostic criteria for FM? First, it is necessary to check the literature on which social variables are associated with FM outcomes. In this regard, a recent study showed several social variables associated with self-care, FM knowledge and social support in these patients [3]. Afterwards, they can simply be added to the checklist used in the current 2016 ACR criteria [4]. Note that the current diagnosis of FM (2016 ACR) does not preclude the presence of other clinically important conditions; however, they are critical to understanding the patient’s prognosis [4, 5]. Therefore, the same must be applied to social variables [3] to examine the patient’s socialization in different contexts when making a diagnosis.

In Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online, there is a sequence of items related to social variables [3]. The blank space is intended to describe each patient’s self-report of their socialization in the observed context, the description of which will show the subjective well-being related to the evaluated social component (i.e. the patient’s socialization and their perceptions and feelings about it). From the descriptions, it is/will be possible to determine whether the patient’s social component is negatively affected or not, and finally to add it to the 2016 ACR criteria [4], allowing a diagnosis divided into two categories: (i) a patient with FM and an impaired social component; and (ii) a patient with FM without an impaired social component.

Another possibility is to bring together the 10 leading FM experts in the world and check their opinions on other social variables that they consider useful to complete the checklist of the social component in the biopsychosocial model. Over the years, experts have changed their position in the global rankings, as this depends on the level of scientific production, as well as its relevance and international reach. Using the Expertscape® ranking to filter experts in FM (https://expertscape.com/ex/fibromyalgia), it is possible to observe the top 10 ranked experts (the outliers) on 11 January 2024. Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online, shows the normal distribution (Gaussian) and the actual distribution of FM experts worldwide, based on 5028 eligible articles published between 2013 and 2023.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Rheumatology online.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this article.

Contribution statement

A.P.-S.—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing (original draft, review and editing).

Funding

A.P.-S. was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grant 2022/08646-6). This study was partially supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, code 001). The funding source had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosure statement: The author has declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), the Federal University of Maranhão (UFMA) and the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), and Maria de Fátima Pontes-Silva (my mother).

Comments