-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marlene Sousa, Patrícia Martins, Bernardo Santos, Emanuel Costa, Filipe Cunha Santos, Raquel Freitas, Margarida Faria, Frederico Martins, Teresa Rodrigues, Tânia Santiago, José A P Silva, Luís S Inês, Anti-Ku antibody syndrome: is it a distinct clinical entity? A cross-sectional study of 75 patients, Rheumatology, Volume 62, Issue 7, July 2023, Pages e213–e215, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kead049

Close - Share Icon Share

Patients with anti-Ku antibodies without other ANA specificities may present a distinct connective tissue disease.

Dear Editor, anti-Ku antibodies (abs) have been associated with several CTD, mainly SLE and inflammatory myositis. However, anti-Ku abs are rare, and just a few studies with a small number of patients have focused on their clinical correlates [1, 2]. Spielmann et al., in a study of 42 anti-Ku positive patients, identified autoantibody biomarkers of two CTD subsets, rarely overlapping, with implications for clinical management: anti-Ku-positive patients with elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels having a high risk of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), and anti-Ku-positive patients with anti-dsDNA antibodies having a high risk of nephritis [3, 4]. We aimed to identify clusters of anti-Ku–positive patients according to their spectrum of ANA specificities and analyse their clinical and analytical features.

We performed a multicentre cross-sectional study of 75 anti-Ku–positive patients at eight rheumatology outpatient clinics. Patients were included in the Rheumatic Diseases Portuguese Registry, which was approved by each hospital Ethics Committee. In addition, a written consent form was obtained from each participant. Data were collected between August 2020 and October 2021. Anti-Ku and other ANA specificities were determined at each hospital’s immunology lab by immunoblotting (EUROblotOne). Cumulative clinical, analytical and treatment features were identified from the patients’ clinical charts. Hierarchical cluster analysis (method: between-groups linkage, squared Euclidian distance) for ANA specificity variables was performed to identify subgroups of anti-Ku–positive patients. Classification performance was evaluated using an appropriate measure for imbalanced data, the geometric mean (G-Mean) [√(sensitivity × specificity)], instead of accuracy, because the latter gives biased performance estimates when the number of cases in each group is skewed.

Of 75 anti-Ku–positive patients included, 73.3% were females, with a mean age at diagnosis of 50.5 (17.9) years and a mean disease duration of 4.7 (5.4) years. In this cohort, established clinical diagnoses were: undifferentiated CTD (26.7%); SLE (17.3%); SS (12.0%); inflammatory myositis (12.0%); SSc (8.0%); RA (4.0%); APS (1.3%); overlap CTD syndrome (1.3%). Healthy carriers of anti-Ku, identified because of screening to rule out a CTD, represented 17.3% of our sample.

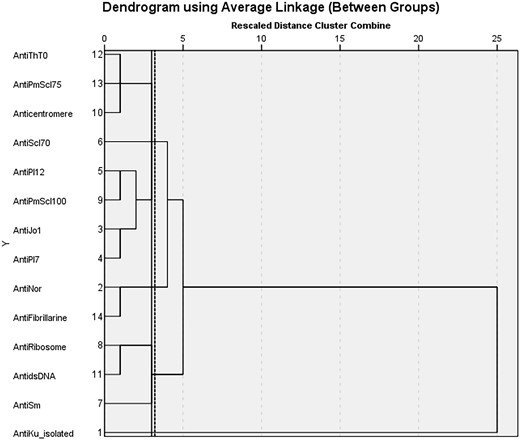

Our analysis identified six autoantibody clusters (Fig. 1): cluster 1 (36.0%)—anti-Ku without any other ANA specificities; cluster 2 (8.0%)—anti-nor90 and anti-fibrillarin; cluster 3 (9.3%)—anti-Jo1, anti-PL-7, anti-PL-12 and anti-PM-Scl100; cluster 4 (4.0%)—anti-Scl70; cluster 5 (13.3%)—anti-Sm, anti-ribosome and anti-dsDNA; cluster 6 (8.0%)—ACA, anti-Th/To and anti-PM-Scl75. The remaining 16 patients were outliers (21.3%), not fitting in any cluster. Other clustering approaches, including organ involvement and treatment variables, did not provide meaningful clusters. In patients from cluster 1, presenting anti-Ku antibodies without any other ANA specificities, the most frequent clinical manifestations were: RP (40.7%), arthritis (25.9%), sicca syndrome (25.9%), myositis (14.8%), and ILD (14.8%); 25.9% were healthy anti-Ku carriers. In the whole cohort, cumulative treatment during follow-up included prednisone, HCQ and/or immunosuppressants in 56.0%, 38.7% and 36.0% of patients, respectively. Patients from cluster 1 were treated with prednisone (51.9%), HCQ (37.0%) and/or immunosuppressants (29.6%).

Hierarchical cluster analysis of ANA specificities in anti-Ku+ patients

Among the whole study population, 18.7% presented major organ involvement: ILD (10.7%) or nephritis (8.0%). No patients from cluster 1 presented nephritis. As a measure of performance for the association of nephritis with anti-dsDNA, the G-Mean was 57.0%. Of the eight patients with ILD, 37.5% had high serum CK, with G-Mean = 56.5%.

Limitations of the study include its cross-sectional design and the limited number of patients with each ANA specificity and types of disease manifestations. The number of patients in each cluster was imbalanced. Considering this, we applied the G-Mean instead of accuracy as a performance measure. Strengths include the larger number of patients compared with previous studies, the multicentre design and the use of cluster analysis for identifying groups of autoantibodies.

Anti-Ku antibodies can be found in various CTDs [5]. In our study, they were found in patients with a diversity of other ANA specificities and heterogeneous CTD diagnoses. Clinical and pathological characteristics are distinct in patients with isolated anti-Ku antibodies [3, 6]. Our findings suggest that anti-Ku–positive patients without any other ANA specificities may represent approximately one-third of all these patients and represent a distinct entity among the differentiated CTDs.

ILD frequently occurred in anti-Ku–positive patients, and this association is confirmed in our study in the single specificity cluster [5, 7]. Arthritis, myositis and RP are also frequent [7, 8]. Some studies reported that elevated CK is associated with ILD [3], and in our study, the G-mean showed there is a moderate association. Likewise, the previously reported association of anti-dsDNA and nephritis in anti-Ku–positive patients [3] presented in our study a moderate association.

Prospective studies with larger populations are needed to further characterize the anti-Ku antibody syndrome.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, L.S.I., upon reasonable request.

Funding

No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Comments