-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Irene Altabás-González, Iñigo Rúa-Figueroa, Francisco Rubiño, Coral Mouriño Rodríguez, Iñigo Hernández-Rodríguez, Raul Menor Almagro, Esther Uriarte Isacelaya, Eva Tomero Muriel, Tarek C Salman-Monte, Irene Carrión-Barberà, Maria Galindo, Esther M Rodríguez Almaraz, Norman Jiménez, Luis Inês, José Maria Pego-Reigosa, Does expert opinion match the definition of lupus low disease activity state? Prospective analysis of 500 patients from a Spanish multicentre cohort, Rheumatology, Volume 62, Issue 3, March 2023, Pages 1162–1169, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keac462

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To apply the lupus low disease activity state (LLDAS) definition within a large cohort of patients and to assess the agreement between the LLDAS and the physician’s subjective evaluation of lupus activity.

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective multicentre study of SLE patients. We applied the LLDAS and assessed whether there was agreement with the clinical status according to the physician’s opinion.

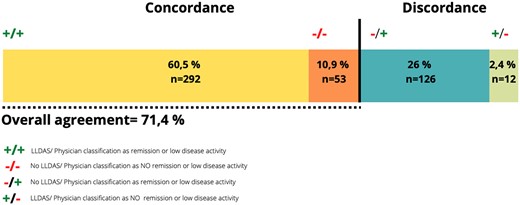

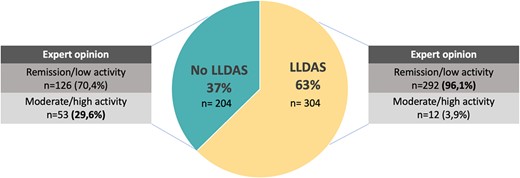

A total of 508 patients [92% women; mean age 50.4 years (s.d. 3.7)] were recruited and 304 (62.7%) patients were in the LLDAS. According to physician assessment, 430 (86.1%) patients were classified as remission or low activity. Overall agreement between both evaluations was 71.4% (95% CI: 70.1, 70.5) with a Cohen’s κ of 0.3 [interquartile range (IQR) 0.22–0.37]. Most cases (96.1%) in the LLDAS were classified as remission or low activity by the expert. Of the patients who did not fulfil the LLDAS, 126 (70.4%) were classified as having remission/low disease activity. The main reasons for these discrepancies were the presence of new manifestations compared with the previous visit and a SLEDAI 2K score >4, mainly based on serological activity.

Almost two-thirds of SLE patients were in the LLDAS. There was a fair correlation between the LLDAS and the physician’s evaluation. This agreement improves for patients fulfilling the LLDAS criteria. The discordance between both at defining lupus low activity, the demonstrated association of the LLDAS with better outcomes and the fact that the LLDAS is more stringent than the physician’s opinion imply that we should use the LLDAS as a treat-to-target goal.

Overall agreement between the LLDAS and the physician’s expert opinion about lupus activity is fair.

The LLDAS is more stringent than the physician’s opinion at defining low SLE activity.

Physicians should use the LLDAS as a treat-to-target goal in clinical practice.

Introduction

SLE is an multisystemic autoimmune disease that can affect almost any organ or tissue with a wide range of clinical manifestations. The particularities of such a heterogeneous disease renders management in everyday clinical practice extremely difficult. It is not only important to keep disease activity under control, but also to prevent drug toxicities and damage accrual, and morbidity and mortality rates in SLE remain high [1] despite diagnostic and therapeutic advances in the disease. Therefore experts in the field are looking for new tools, such as treat-to-target (T2T) strategies [2], that may improve outcomes and guide clinicians in the management of this complex disease.

The T2T approach in other rheumatic conditions such as RA, SpA and PsA is well established in clinical practice. In RA patients it has led to better management of the disease and damage prevention compared with routine control [3]. The main objective of the T2T strategy is to define a specific therapeutic goal, which would be clinical remission, or if that is not possible, low activity of the disease. In the last few years the definitions of remission in SLE by the Definition of Remission in SLE (DORIS) task force [4] and the lupus low disease activity state (LLDAS) [5] by the Asia-Pacific Lupus Collaboration (APLC) have emerged with the aim of being implemented as a T2T approach in SLE.

The DORIS task force defined remission in four different states, mainly depending on whether the patient is receiving treatment (apart from antimalarials) or not and also on whether the patient has serological activity or not. The Safety of Estrogens in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment (SELENA)–SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) physician global assessment (PGA; scale 0–3) must be <0.5. Two remission states are complete remission (SLEDAI-2K = 0) and clinical remission (clinical SLEDAI-2K = 0; hypocomplementemia and the presence of anti-dsDNA antibodies are allowed). In these two clinical states, treatments apart from antimalarials are not allowed. The other two remission states are complete remission on treatment (complete ROT) and clinical remission on treatment (clinical ROT). In these two remission states, treatment with a maximum of 5 mg/day prednisolone and immunosuppressive drugs (conventional immunomodulators and biologics) is allowed. More recently, it has been proposed that the most appropriate of these four definitions of remission would be the one that corresponds to clinical ROT [6]. On the other hand, the LLDAS is based on the following criteria: SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, central nervous system, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis and fever) and no haemolytic anaemia or gastrointestinal activity; no new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment; SELENA-SLEDAI PGA ≤1; current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day and well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs [5].

These clinical states have been analysed in other cohorts, showing beneficial effects on reducing damage accrual, flares and hospitalizations and improving quality of life scores [6–11]. However, the different studies showed that they are difficult to achieve and/or maintain over time [12–16].

The objective of our study is to analyse the agreement between the LLDAS definition and the clinical status of the patient according to the expert opinion of the rheumatologist and explore modifications in the LLDAS definition that may improve it.

Study design

We are carrying out a national, multicentre, longitudinal study in order to evaluate the association of the LLDAS with other outcomes such as damage accrual. The study is currently on-going, with data collection taking place once a year over 3 consecutive years using a standardized electronic case report form. The current study corresponds to the cross-sectional analysis of the baseline data. A specific protocol was created to collect data on ∼250 variables per patient. To ensure data homogeneity and quality, every item in the protocol has a highly standardized definition. A previous training course for investigators was carried out to avoid information bias. All investigators had online access to guidelines on how to complete the protocol. Patients were recruited at seven Spanish rheumatology departments. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Galicia. All patients signed an informed consent form prior to participation.

Patients

We included consecutive patients in the outpatient clinic setting. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years and a diagnosis of SLE according to the revised 1997 ACR classification criteria or the 2012 SLICC classification criteria for SLE [17, 18]. There were no specific exclusion criteria. To avoid selection bias, patients were recruited homogeneously across Spain. Virtually all patients with SLE treated in our country are referred to hospitals, thus avoiding the possibility of centre selection bias.

Variables

At recruitment, demographics, SLE criteria, SLE clinical variables, subjective evaluation of the disease by the rheumatologist and the patient and data about treatments were collected. Most of these variables were then collected on a yearly basis. Demographic variables included gender, date of birth and date of definite SLE diagnosis.

Disease activity in the previous 30 days was measured using the SLEDAI-2K [19] and the 28 tender/swollen joint count was also evaluated. Laboratory results for the SLEDAI-2K, ESR and CRP within 30 days of the visit were also collected. Clinical manifestations of SLE activity not included in the SLEDAI were also measured. Organ damage was assessed using the SLICC/ACR damage index (SDI) [20].

The expert rheumatologists were asked to categorize patients into five different clinical states: remission, serologically active, low disease activity, moderate disease activity and high disease activity. The PGA on a scale of 0–3 and patient global assessment on a scale of 0–10 were also captured. Treatment variables included current use and dose of antimalarials, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressive treatments and biologic agents.

The disease activity, measured by the SLEDAI-2K, of each patient visit was compared with the previous one and classified by the expert rheumatologist as clinically meaningful improvement, no clinically meaningful change in disease activity or clinically meaningful worsening.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

We calculated the number of patients needed for different levels of agreement, considering that 60% of SLE patients are typically estimated to be in remission or low disease activity and 40% of patients are not. We estimated a sample size of 96 patients to obtain 80% statistical power with a significance level of 0.05.

Only the first visit was analysed for the current study. The data from a first patient visit were compared with the data available in the electronic records from the previous visit. Achievement of remission and the LLDAS were obtained according to the predefined criteria. Results were expressed as mean (s.d.) for continuous variables and as number of patients (percentage) for binary and categorical variables. Expert evaluation of global disease activity was divided into two groups: remission/serologically active clinically quiescent (SACQ)/low activity and moderate/high activity and were compared with the LLDAS definition in a two-by-two table assessing the agreement between the physician’s expert opinion and the LLDAS definition. The percentage of agreement and Cohen’s κ were used as measures of agreement between the LLDAS and physician evaluation. The percentage of agreement was calculated as the number of agreement scores divided by the total number of scores. The Cohen’s κ coefficient (the agreement among the measures other than what would be expected by chance) was used to evaluate the degree of concordance/reliability between the two measures: κ < 0, no agreement; κ = 0–0.20, slight agreement; κ = 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; κ = 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; κ = 0.61–0.80, substantial agreement; and κ = 0.81–1.0, perfect agreement [21].

Cases in which there was a disagreement between both evaluations were further analysed to evaluate which of the LLDAS criteria contributed most to the discrepancy. Then we carried out a sensitivity analysis, making several changes in the LLDAS criteria, which were modified to check to see if this led to a change in the overall agreement: prednisone doses were adjusted from ≤7.5 mg/day to ≤5 mg/day, SLEDAI-2K from ≤4 to clinical (excluding serological activity) SLEDAI-2K ≤4, exclusion of the LLDAS criterion ‘no new features compared with previous assessment’ and finally combining the three of them.

P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with R statistical software, version 4.0.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographics and disease characteristics

A total of 508 patients were recruited. In this cohort, 92% of patients were female, with a mean age at diagnosis of 40.7 years (s.d. 21) and a mean disease duration of 10.8 years (s.d. 9.9) at the time of recruitment. The mean age at recruitment was 50.4 years (s.d. 13.7). Previous disease manifestations were determined from the SLICC 2012 criteria on an ‘ever present’ basis. The most common clinical criteria were arthritis in 69.8% of the patients, cutaneous rash in 62.7% and leucopoenia in 43.11%. A total of 491 patients (96.65%) were ANA positive, 64.76% had high anti-dsDNA levels and 60.24% had low complement levels. A total of 167 patients (31%) had a history of lupus nephritis. At the time of the first visit of the study, the mean SLEDAI-2K score was 2.8 (s.d. 3.3) and the mean SDI score was 0.96 (s.d. 1.36). More detailed information about the demographics and clinical information of the cohort is depicted in Table 1.

| Characteristics . | Values . |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 460 (92%) |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (s.d.) | 40.7 (21.0) |

| Disease duration at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 10.8 (9.9) |

| Age at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 50.4 (13.7) |

| SLICC 2012 criteria (ever present) | |

| Clinical criteria, n (%) | |

| Acute cutaneous lupus | 262 (51.57) |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus | 57 (11.22) |

| Oral or nasal ulcers | 171 (33.66) |

| Non-scaring alopecia | 156 (30.71) |

| Arthritis | 355 (69.88) |

| Serositis | 96 (18.9) |

| Renal | 158 (31.1) |

| Neurologic | 32 (6.3) |

| Haemolytic anaemia | 29 (5.7) |

| Leukopenia | 219 (43.11) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 88 (17.3) |

| Immunological criteria, n (%) | |

| ANA | 489 (96.26) |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 329 (64.76) |

| Anti-Sm antibodies | 95 (18.7) |

| Anti-phospholipid antibodies | 163 (32.09) |

| Low complement levels | 306 (60.24) |

| Number of SLICC criteria for SLE, n (%) | 6.2 (2.2) |

| SLEDAI-2K score at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 2.8 (3.3) |

| SLICC/ACR-DI score at enrolment mean (s.d.) | 0.96 (1.4) |

| Damage present at enrolment, n (%) | 253 (49.8) |

| Clinical SLEDAI-2K score, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (2.7) |

| Current hypocomplementemia, n (%) | 152 (29.9) |

| Current elevated anti-dsDNA, n (%) | 125 (24.6) |

| PGA at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 0.2 (0.49) |

| Characteristics . | Values . |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 460 (92%) |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (s.d.) | 40.7 (21.0) |

| Disease duration at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 10.8 (9.9) |

| Age at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 50.4 (13.7) |

| SLICC 2012 criteria (ever present) | |

| Clinical criteria, n (%) | |

| Acute cutaneous lupus | 262 (51.57) |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus | 57 (11.22) |

| Oral or nasal ulcers | 171 (33.66) |

| Non-scaring alopecia | 156 (30.71) |

| Arthritis | 355 (69.88) |

| Serositis | 96 (18.9) |

| Renal | 158 (31.1) |

| Neurologic | 32 (6.3) |

| Haemolytic anaemia | 29 (5.7) |

| Leukopenia | 219 (43.11) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 88 (17.3) |

| Immunological criteria, n (%) | |

| ANA | 489 (96.26) |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 329 (64.76) |

| Anti-Sm antibodies | 95 (18.7) |

| Anti-phospholipid antibodies | 163 (32.09) |

| Low complement levels | 306 (60.24) |

| Number of SLICC criteria for SLE, n (%) | 6.2 (2.2) |

| SLEDAI-2K score at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 2.8 (3.3) |

| SLICC/ACR-DI score at enrolment mean (s.d.) | 0.96 (1.4) |

| Damage present at enrolment, n (%) | 253 (49.8) |

| Clinical SLEDAI-2K score, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (2.7) |

| Current hypocomplementemia, n (%) | 152 (29.9) |

| Current elevated anti-dsDNA, n (%) | 125 (24.6) |

| PGA at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 0.2 (0.49) |

| Characteristics . | Values . |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 460 (92%) |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (s.d.) | 40.7 (21.0) |

| Disease duration at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 10.8 (9.9) |

| Age at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 50.4 (13.7) |

| SLICC 2012 criteria (ever present) | |

| Clinical criteria, n (%) | |

| Acute cutaneous lupus | 262 (51.57) |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus | 57 (11.22) |

| Oral or nasal ulcers | 171 (33.66) |

| Non-scaring alopecia | 156 (30.71) |

| Arthritis | 355 (69.88) |

| Serositis | 96 (18.9) |

| Renal | 158 (31.1) |

| Neurologic | 32 (6.3) |

| Haemolytic anaemia | 29 (5.7) |

| Leukopenia | 219 (43.11) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 88 (17.3) |

| Immunological criteria, n (%) | |

| ANA | 489 (96.26) |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 329 (64.76) |

| Anti-Sm antibodies | 95 (18.7) |

| Anti-phospholipid antibodies | 163 (32.09) |

| Low complement levels | 306 (60.24) |

| Number of SLICC criteria for SLE, n (%) | 6.2 (2.2) |

| SLEDAI-2K score at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 2.8 (3.3) |

| SLICC/ACR-DI score at enrolment mean (s.d.) | 0.96 (1.4) |

| Damage present at enrolment, n (%) | 253 (49.8) |

| Clinical SLEDAI-2K score, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (2.7) |

| Current hypocomplementemia, n (%) | 152 (29.9) |

| Current elevated anti-dsDNA, n (%) | 125 (24.6) |

| PGA at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 0.2 (0.49) |

| Characteristics . | Values . |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 460 (92%) |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (s.d.) | 40.7 (21.0) |

| Disease duration at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 10.8 (9.9) |

| Age at enrolment, years, mean (s.d.) | 50.4 (13.7) |

| SLICC 2012 criteria (ever present) | |

| Clinical criteria, n (%) | |

| Acute cutaneous lupus | 262 (51.57) |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus | 57 (11.22) |

| Oral or nasal ulcers | 171 (33.66) |

| Non-scaring alopecia | 156 (30.71) |

| Arthritis | 355 (69.88) |

| Serositis | 96 (18.9) |

| Renal | 158 (31.1) |

| Neurologic | 32 (6.3) |

| Haemolytic anaemia | 29 (5.7) |

| Leukopenia | 219 (43.11) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 88 (17.3) |

| Immunological criteria, n (%) | |

| ANA | 489 (96.26) |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 329 (64.76) |

| Anti-Sm antibodies | 95 (18.7) |

| Anti-phospholipid antibodies | 163 (32.09) |

| Low complement levels | 306 (60.24) |

| Number of SLICC criteria for SLE, n (%) | 6.2 (2.2) |

| SLEDAI-2K score at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 2.8 (3.3) |

| SLICC/ACR-DI score at enrolment mean (s.d.) | 0.96 (1.4) |

| Damage present at enrolment, n (%) | 253 (49.8) |

| Clinical SLEDAI-2K score, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (2.7) |

| Current hypocomplementemia, n (%) | 152 (29.9) |

| Current elevated anti-dsDNA, n (%) | 125 (24.6) |

| PGA at enrolment, mean (s.d.) | 0.2 (0.49) |

In total, 371 (74%) patients were on antimalarials, 199 (39%) patients were on prednisone, with a mean daily dose of 2.5 mg (s.d. 5), and 219 (44%) patients were receiving conventional immunosuppressants and/or biologics (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online).

Frequency of the LLDAS and remission states

All five criteria for the LLDAS were fulfilled in 304 (62.7%) of the 508 patients. Of the criteria related to the evaluation of disease activity, the most frequently met was PGA ≤1 in 471 (95.1%) patients. The least frequent one was the SLEDAI-2K ≤4, in 462 (80%) patients. In contrast, of the criteria related to treatments, the glucocorticoid criterion was achieved in 470 (92.5%) patients. More detailed information about the frequency of the LLDAS criteria is shown in Table 2.

| Descriptors of disease activity . | Number (%) (N = 508) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 462 (80.0) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 410 (83) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 451 (95.1) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 470 (92.5) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | 508 (100) |

| All five criteria present | 304 (62.7) |

| Descriptors of disease activity . | Number (%) (N = 508) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 462 (80.0) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 410 (83) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 451 (95.1) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 470 (92.5) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | 508 (100) |

| All five criteria present | 304 (62.7) |

| Descriptors of disease activity . | Number (%) (N = 508) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 462 (80.0) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 410 (83) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 451 (95.1) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 470 (92.5) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | 508 (100) |

| All five criteria present | 304 (62.7) |

| Descriptors of disease activity . | Number (%) (N = 508) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 462 (80.0) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 410 (83) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 451 (95.1) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 470 (92.5) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | 508 (100) |

| All five criteria present | 304 (62.7) |

Clinical remission was achieved in 133 (27.3%) patients and complete remission in 118 (24.4%). A less stringent definition of remission in which treatment is allowed was met in 267 (54.4%) and 218 (46.4%) cases for clinical ROT and complete ROT, respectively. A total of 267 patients (87.82%) who fulfilled the LLDAS criteria were also in clinical ROT.

SLE disease activity according to the expert opinion of the rheumatologist

A total of 430 (86.1%) patients were classified as in remission, SACQ or low activity following the assessment of the rheumatologist. Of these, remission was observed in 206 (41.6%), SACQ in 71 (14.3%) and low activity in 153 (30.9%). A total of 55 patients (11.1%) were classified as having moderate activity and 10 (2%) patients as having high activity.

Agreement between expert opinion of remission/low activity and LLDAS

The overall agreement between expert opinion of remission/low activity and LLDAS was 71.4% (95% CI 70.1, 70.5) with a Cohen’s κ of 0.3 (IQR 0.22–0.37) (Fig. 1). Most of the cases (96.1%) that fulfilled the definition of LLDAS were classified by the expert as remission, serologically active or low activity. Only 12 (3.9%) patients were classified as moderate or high activity by the expert. Of these 12 patients, 3 had arthritis, 2 had hypocomplementemia and one each had myositis, high anti-dsDNA values, thrombocytopenia, rash and mucosal ulcers. On the other hand, of the patients who did not fulfil the definition of LLDAS, 126 of 179 (70.4%) were classified by the expert as remission, serologically active or low disease activity (Fig. 2). The main reasons for discrepancies in the group that did not fulfil the definition of LLDAS were the presence of new clinical features compared with the previous visit and a SLEDAI-2K score >4, in 74 (58.7%) and 59 (46.8%) patients, respectively. More detailed information about discrepancies is shown in Table 3. We also analysed the items of the SLEDAI-2K exceeding 4 points (Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online).

Agreement between the LLDAS and physician classification as remission/low disease activity

Reason for disagreement between patients who did not fulfil the LLDAS definition and physician assessment as remission or low disease activity

| Descriptors of disease activity . | LLDAS not achieved, n (%) (N = 126%) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 59 (46.8) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 74 (58.7) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 4 (3.3) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 16 (12.7) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | |

| Descriptors of disease activity . | LLDAS not achieved, n (%) (N = 126%) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 59 (46.8) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 74 (58.7) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 4 (3.3) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 16 (12.7) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | |

Reason for disagreement between patients who did not fulfil the LLDAS definition and physician assessment as remission or low disease activity

| Descriptors of disease activity . | LLDAS not achieved, n (%) (N = 126%) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 59 (46.8) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 74 (58.7) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 4 (3.3) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 16 (12.7) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | |

| Descriptors of disease activity . | LLDAS not achieved, n (%) (N = 126%) . |

|---|---|

| SLEDAI-2K ≤4, with no activity in major organ systems (renal, CNS, cardiopulmonary, vasculitis, haemolytic anaemia, fever) and no gastrointestinal activity | 59 (46.8) |

| No new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment | 74 (58.7) |

| PGA (scale 0–3) ≤1 | 4 (3.3) |

| Immunosuppressive medications | |

| Current prednisolone (or equivalent) dose ≤7.5 mg/day | 16 (12.7) |

| Well-tolerated standard maintenance doses of immunosuppressive drugs and approved biologic agents, excluding investigational drugs | |

We adjusted the following criteria of the LLDAS definition to determine whether there was a variation in agreement: prednisone dose to 5 mg/day, clinical SLEDAI-2K ≤ 4, exclusion of the criteria ‘no new features of lupus disease activity compared with previous assessment’ and the combination of the three. The adjustment that brought about the most significant increase in agreement was the exclusion of the comparative features with the previous visit, with agreement going from 71.4% to 82.6% (95% CI 81.61, 83.96) with a Cohen’s κ of 0.45 (IQR 0.36–0.55). Lowering the cut-off point of prednisone to 5 mg/day did not change the level of agreement or produce a significant change in the percentage of patients in the LLDAS (Table 4).

Agreement between expert opinion of remission/low activity and the LLDAS or modified LLDAS

| Expert opinion . | Agreement, % (95% CI) . | Cohen’s κ (IQR) . |

|---|---|---|

| LLDAS original definition | 71.4 (70.17, 70.54) | 0.3 (0.22–0.37) |

| (a) LLDAS modified: cSLEDAI-2K ≤4 excluding serology | 74.2 (72.34, 75.66) | 0.23 (0.18–0.36) |

| (b) LLDAS modified: prednisone ≤5 mg/day | 70.3 (68.75, 72.04) | 0.29 (0.21–0.36) |

| (c) LLDAS modified: excluding ‘no new clinical features compared with previous’ | 82.6 (81.38, 83.96) | 0.45 (0.36–0.55) |

| LLDAS modified (a), (b) and (c) | 80.75 (79.14, 82.29) | 0.42 (0.33–0.51) |

| Expert opinion . | Agreement, % (95% CI) . | Cohen’s κ (IQR) . |

|---|---|---|

| LLDAS original definition | 71.4 (70.17, 70.54) | 0.3 (0.22–0.37) |

| (a) LLDAS modified: cSLEDAI-2K ≤4 excluding serology | 74.2 (72.34, 75.66) | 0.23 (0.18–0.36) |

| (b) LLDAS modified: prednisone ≤5 mg/day | 70.3 (68.75, 72.04) | 0.29 (0.21–0.36) |

| (c) LLDAS modified: excluding ‘no new clinical features compared with previous’ | 82.6 (81.38, 83.96) | 0.45 (0.36–0.55) |

| LLDAS modified (a), (b) and (c) | 80.75 (79.14, 82.29) | 0.42 (0.33–0.51) |

Agreement between expert opinion of remission/low activity and the LLDAS or modified LLDAS

| Expert opinion . | Agreement, % (95% CI) . | Cohen’s κ (IQR) . |

|---|---|---|

| LLDAS original definition | 71.4 (70.17, 70.54) | 0.3 (0.22–0.37) |

| (a) LLDAS modified: cSLEDAI-2K ≤4 excluding serology | 74.2 (72.34, 75.66) | 0.23 (0.18–0.36) |

| (b) LLDAS modified: prednisone ≤5 mg/day | 70.3 (68.75, 72.04) | 0.29 (0.21–0.36) |

| (c) LLDAS modified: excluding ‘no new clinical features compared with previous’ | 82.6 (81.38, 83.96) | 0.45 (0.36–0.55) |

| LLDAS modified (a), (b) and (c) | 80.75 (79.14, 82.29) | 0.42 (0.33–0.51) |

| Expert opinion . | Agreement, % (95% CI) . | Cohen’s κ (IQR) . |

|---|---|---|

| LLDAS original definition | 71.4 (70.17, 70.54) | 0.3 (0.22–0.37) |

| (a) LLDAS modified: cSLEDAI-2K ≤4 excluding serology | 74.2 (72.34, 75.66) | 0.23 (0.18–0.36) |

| (b) LLDAS modified: prednisone ≤5 mg/day | 70.3 (68.75, 72.04) | 0.29 (0.21–0.36) |

| (c) LLDAS modified: excluding ‘no new clinical features compared with previous’ | 82.6 (81.38, 83.96) | 0.45 (0.36–0.55) |

| LLDAS modified (a), (b) and (c) | 80.75 (79.14, 82.29) | 0.42 (0.33–0.51) |

Discussion

Treating a disease to an objective target state has been applied in the management of several chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. This T2T approach has been implemented in different rheumatic diseases, including RA, PsA and SpA, in which the optimal target is generally considered the lowest level of activity achievable (remission or low disease activity) [3, 22, 23]. This approach, together with tight monitoring and control, have substantially changed the course of these diseases, with better long-term outcomes [24].

In the last few years there has been increased interest in adopting a similar therapeutic strategy for SLE and new concepts of remission and low disease activity have emerged. The ultimate goal in SLE is long-term survival and the prevention of organ damage, with adequate control of disease activity and management minimizing the irreversible effects of treatments. Thus the definition of remission and low disease activity in SLE includes both the activity and treatment domains as well as the expert assessment (scale 0–3) [2, 4, 5].

The current definition of the LLDAS has been validated prospectively and shown to be associated with reduced flare rates and damage accrual in different international SLE cohorts [5, 7–9, 15, 25–32]. The protective effect of the LLDAS on damage accrual has also been demonstrated in the early stages of SLE in different inception cohorts [8, 27, 29]. A multicentre study in the UK described that the achievement of the LLDAS and remission was also associated with a significantly lower risk of severe flare/new damage in childhood SLE [9]. As important as the aforementioned is, the demonstration that achievement of the LLDAS is associated with a significant reduction in mortality in SLE patients, including those newly diagnosed [8, 32]. It has also been seen that the LLDAS has a favourable impact on other outcome measures, such as a better health-related quality of life [30, 32–34], better pregnancy outcomes [35] and decreased direct hospital healthcare costs [36]. All these associations make the LLDAS a useful tool for a real-world T2T setting.

In the first visit of our study, around two-thirds of the patients met the LLDAS definition while the different categories of remission were reached in 24.4% and 54.4% for complete remission and clinical ROT, respectively. These remission and LLDAS rates are similar to rates previously reported in Europe [25, 37]. Although remission is a more ambitious goal, it is more difficult to achieve and maintain over time [16].

In this analysis, we evaluated the agreement of the LLDAS definition with the physician’s expert opinion of remission/low activity. We applied the LLDAS definition to our cohort of patients and, at the same time, asked the treating clinician to classify the patient into five different categories (remission, serological activity, low, moderate or high activity). The overall agreement between these two evaluations was fair. Although the agreement in the group in the LLDAS was 96%, there was an important percentage of patients that physicians considered in remission or low activity but did not reach the LLDAS definition. This can indicate that clinicians may think that patients are in remission/low activity when they are not in the LLDAS and therefore are at risk of damage accrual. This finding suggests that clinicians should use the LLDAS as a T2T goal in clinical practice as the LLDAS achievement has been associated with better outcomes.

Further analysis revealed that the main reasons for this disagreement were the presence of new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment (58.7% of cases) and the non-fulfilment of SLEDAI-2K ≤4 (46.7%). Only in 16 (12.7%) of those patients, the reason for the disagreement was the fact that they were taking >7.5 mg/day of prednisone. One explanation could be that they were receiving >7.5 mg/day for another reason and that therefore the physician considered the patient in remission or low activity from the point of view of SLE.

When we analysed in detail the domains of the SLEDAI-2K score of those patients exceeding 4 points, we observed that around two-thirds of them had serological activity (positive anti-dsDNA antibodies or hypocomplementemia) with another clinical manifestation. This can suggest that physicians do not give the same kind of weight to these serological domains when evaluating low disease activity. On the other hand, it is known that the SLEDAI-2K score does not discriminate the severity of a clinical manifestation while the treating physician does. Physicians may not qualify stable persistent clinical manifestations as important forms of disease activity.

On the other hand, based on our findings, we think that serologic findings may play an excessive role in the achievement or not of the LLDAS, as frequently active manifestations such as arthritis or mucocutaneous involvement are allowed in the LLDAS as long as there is no serological activity, while neither of them is allowed to classify as LLDAS in serologically active patients. Thus the LLDAS is more stringent in serological active than in serologically quiescent patients. In fact, in patients with hypocomplementemia and positive anti-dsDNA, no clinical activity is allowed for the LLDAS.

Another important observation is that almost two-thirds of the patients who did not fulfil the LLDAS and who the physician considered in remission or low disease activity had different clinical manifestations compared with a previous assessment. This is explained by the heterogeneity of the disease itself, as it can be present in different clinical forms. Also, we did not establish a minimum period of time to compare visits, so a second visit could have been distant in time with respect to our baseline visit. Thus when we analysed a change in the LLDAS definition by eliminating ‘no new features of lupus disease activity compared with the previous assessment’, this led to an increase in agreement between the LLDAS definition and the physician’s opinion. However, further analysis is needed to see how this change in the LLDAS definition could affect damage prevention and other outcomes.

The prednisone dose cut-off point of 7.5 mg/day in the LLDAS definition would be deemed by many to be an unacceptably high maintenance dose to classify a patient as low disease activity. as the harmful long-term effects of this therapy, even at low doses, are well known. We observed that a modification in the cut-off point of the prednisone dose in the LLDAS to 5 mg/day does not imply an important change regarding the original definition in our cohort, neither in the percentage of patients fulfilling the LLDAS definition nor in the agreement with the expert rheumatologist’s assessment. The daily prednisone dose of 5 mg is the same as in the DORIS definition of remission and the lowering of the permitted threshold to 5 mg might have a significant favourable impact in future damage.

Our study is limited by the cross-sectional design of the first visit. The current study is only the baseline analysis of the cohort and the longitudinal stage of our project will allow us to assess the impact of maintaining remission and the LLDAS over time, as well as the impact of maintaining these states according to the physician’s classification on different long-term outcomes such as damage, hospitalization and quality of life.

In conclusion, we found that the LLDAS is a feasible target in the T2T strategy in the management of SLE patients. The overall agreement between the LLDAS and the physician’s expert opinion about SLE activity is fair, although improves considerably in patients who achieve the LLDAS. The main reasons for the discrepancy in patients who do not achieve the LLDAS are the appearance of clinical manifestations different from the ones in the previous evaluation and a SLEDAI-2K score >4, mainly based on serological activity. This discrepancy implies a greater number of patients considered in low disease activity by the physician when the patient really is not in the LLDAS, so the LLDAS is a more stringent tool than the physician’s opinion in defining low SLE activity. This suggests we should use the LLDAS as a T2T goal in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the FIS/ISCIII-Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo regional (grant PI17/01366). I.A.-G. is supported by ACI/FER (21/CONV/02/1266).

Funding: No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

Comments