-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Manphool Singhal, Rakesh Kumar Pilania, Ankur Kumar Jindal, Aman Gupta, Avinash Sharma, Sandesh Guleria, Nameirakpam Johnson, Muniraju Maralakunte, Pandiarajan Vignesh, Deepti Suri, Manavjit Singh Sandhu, Surjit Singh, Distal coronary artery abnormalities in Kawasaki disease: experience on CT coronary angiography in 176 children, Rheumatology, Volume 62, Issue 2, February 2023, Pages 815–823, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keac217

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Precise evaluation of coronary artery abnormalities (CAAs) in Kawasaki disease (KD) is essential. The aim of this study is to determine role of CT coronary angiography (CTCA) for detection of CAAs in distal segments of coronary arteries in patients with KD.

CTCA findings of KD patients with distal coronary artery involvement were compared with those on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) during the period 2013–21.

Among 176 patients with KD who underwent CTCA (128-Slice Dual Source scanner), 23 (13.06%) had distal CAAs (right coronary—15/23; left anterior descending—14/23; left circumflex—4/23 patients). CTCA identified 60 aneurysms—37 proximal (36 fusiform; 1 saccular) and 23 distal (17 fusiform; 6 saccular); 11 patients with proximal aneurysms had distal contiguous extension; 9 patients showed non-contiguous aneurysms in both proximal and distal segments; 4 patients showed distal segment aneurysms in absence of proximal involvement of same coronary artery; 4 patients had isolated distal CAAs. On TTE, only 40 aneurysms could be identified. Further, distal CAAs could not be identified on TTE. CTCA also identified complications (thrombosis, mural calcification and stenosis) that were missed on TTE.

CAAs can, at times, occur in distal segments in isolation and also in association with, or extension of, proximal CAAs. CTCA demonstrates CAAs in distal segments of coronary arteries, including branches, in a significant number of children with KD—these cannot be detected on TTE. CTCA may therefore be considered as a complimentary imaging modality in children with KD who have CAAs on TTE.

Rheumatology key messages

Precise evaluation of coronary artery abnormalities (CAAs) is essential for clinical decision making in Kawasaki disease (KD).

CT coronary angiography demonstrates distal segments CAAs in a significant number of children with KD.

CAAs can also occur in distal segments of coronary arteries—in isolation or extension of proximal CAAs.

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is a common childhood vasculitic disorder. It has a predilection for coronary artery involvement [1, 2]. Coronary artery abnormalities (CAAs) can occur in 15–25% of children with KD who do not receive treatment [1, 3]. Even with prompt institution of appropriate treatment, 3–5% children go on to develop CAAs [1, 3]. 2D transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has hitherto been the standard of care for evaluating children with KD for CAAs [1, 4, 5]. However, it has now become clear that TTE has several limitations [6, 7].

While TTE has high sensitivity and specificity to pick up proximal-segment CAAs, its sensitivity in diagnosis of mid- and distal-segment CAAs (grouped hereafter as distal CAAs) remains poor. This leads to under-recognition of distal CAAs in KD [5, 7–9]. TTE is also operator dependent and has inter-observer variability [4, 9]. Conventional catheter coronary angiography (CCA) is the gold standard for delineation of CAAs along the entire course of coronary arteries. CCA, however, is an invasive modality, often requires sedation/anaesthesia in young children, carries significant radiation exposure and cannot be repeated on follow-up [7, 9–11].

CT coronary angiography (CTCA) is now emerging as an important imaging modality with sensitivity and specificity that is comparable to CCA for delineation and characterization of CAAs in patients with KD [6, 7, 9, 12]. It is non-invasive and can readily be repeated at follow-up. In children over 5 years old, it can be performed without any sedation. With the availability of high detector and dual source CT platforms, CTCA has now emerged as a low-radiation imaging paradigm in patients with KD [6, 9]. Advantages over TTE include the ability to visualize coronary arteries over the entire length with little or no inter-observer variability. CTCA clearly delineates both intramural and extramural abnormalities [6, 7, 9, 12]. Yu et al. have compared TTE and CTCA for evaluation of CAAs in patients with KD. The authors reported that while both modalities were equally effective for imaging of proximal segments of coronary arteries, CTCA provided more explicit delineation of distal segments than TTE [13].

It is uncommon to have CAAs in distal segments in absence of proximal segment involvement in children with KD [1, 14]. Tsuda et al. have investigated the relationship between severity and distribution of CAAs on CCA and showed the that larger the diameter of coronary artery aneurysm, the greater is the involvement of distal segments [15]. Treatment intensification and treatment duration in KD, however, depends on presence and then complete regression of CAAs in both proximal and distal segments. Therefore, it is important to evaluate and delineate CAAs in all segments of coronary arteries for clinical decision making. In this context we report herein our experience of CTCA for detection of CAAs in distal segments of coronary arteries in patients with KD. This is primarily a descriptive study to highlight the role of CTCA in evaluation of CAAs in distal segments of coronary arteries in children with KD.

Methods

We reviewed CTCA data of 176 patients with KD during the period November 2013 to June 2021 at a federally funded, not-for-profit, tertiary care teaching institute. Diagnosis of KD was based on American Heart Association guidelines [1, 16]. Children having distal coronary artery involvement were identified and analysed in detail. Corresponding findings on TTE were also recorded. Patient demographics (age at diagnosis of KD; age when CTCA and TTE were performed), TTE and CTCA findings were recorded on a predesigned proforma. The study protocol was approved by Institute Ethics Committee (IEC No. NK/1837/Res/2890). The manuscript was also approved by Departmental Publication Review Board. Informed written consent was obtained from parents before performing CTCA.

CTCA was performed on a 128-Slice DSCT scanner (Somatom definition flash, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using non-ionic contrast (Omnipaque 350, GE Healthcare, Ireland). In children under 5 years of age oral triclofos and/or i.v. midazolam was used for sedation. None of the children required general anaesthesia. Radiation exposure was optimized using adaptive prospective electrocardiography-gated sequence, automated tube current modulation (care dose 4D; Siemens Healthineers), lower kilo-voltage settings (fixed at 80 kVp) and iterative image reconstruction algorithms (Safire; Siemens Healthineers). Radiation exposure was below 1 millisievert (mSv). Post-processing analysis was carried out on a dedicated Syngovia (Siemens Healthineers) workstation for reconstruction and evaluation of coronary arteries.

All CTCAs were reviewed by a single, experienced cardiac radiologist (M.S.) who was blinded to clinical details and TTE findings. Coronary arteries and side branches were included in analysis wherever these were visualized. CAAs were evaluated in terms of location, number and morphology (aneurysms—saccular/fusiform; dilatation). The term aneurysm was used if internal diameter of coronary artery was ≥1.5 times that of an adjacent segment. Coronary arteries were said to be dilated if the internal diameter was increased but was <1.5 times that of an adjacent segment [7]. In addition, complications such as intra-luminal thrombosis, mural calcification and stenosis were also noted. TTE was performed as per standard protocol. CAAs on TTE were recorded and results compared with CTCA findings.

Results

Review of records of 176 children (n = 176) where CTCA and TTE were performed yielded 23 patients (23/176; 13.06%) who had distal CAAs. Eighteen patients underwent CTCA at presentation of KD and five patients (S. nos 7, 8, 11, 14 and 21) on follow-up. Median age at diagnosis of disease was 3.5 years (2 months to 11 years) in this cohort of 23 patients.

Details of CAAs in these patients were as follows (Table 1 and supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online):

Abnormalities on CTCA in children with KD having distal coronary artery involvement

| Patient no. . | Details of aneurysms in proximal segments of coronary arteries (n) . | Details of aneurysms in distal segments of coronary arteries (n) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 2 | LCA extending into LADS (1) | RCAS (1) |

| 3 | LADF@ (1); LCxF@(1); RCAF (1) | LADS (1); RCAS (multiple); aneurysm in proximal LAD and LCx extended into distal segment |

| 4 | LCA extending into LADF (1); RCAF (1); LCx non-opacified | RCAS (1) |

| 5 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1); LCx non-opacified | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 6 | LCA extending LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 7 | LADF@ (1); LCxF (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 8 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 9 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 10 | No CAAs | RCAF (1) |

| 11 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 12 | LADF@ (1) | LADS (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 13 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF (multiple) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 14 | No CAAs | LCxS (multiple) |

| 15 | LADF (1) | LCxF (1) |

| 16 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 17 | LCAF (1); LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal RCA extended into distal segment |

| 18 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF@ (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 19 | LCA extending into LAD and LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (1) |

| 20 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 21 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 22 | LCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

| 23 | LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

| Patient no. . | Details of aneurysms in proximal segments of coronary arteries (n) . | Details of aneurysms in distal segments of coronary arteries (n) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 2 | LCA extending into LADS (1) | RCAS (1) |

| 3 | LADF@ (1); LCxF@(1); RCAF (1) | LADS (1); RCAS (multiple); aneurysm in proximal LAD and LCx extended into distal segment |

| 4 | LCA extending into LADF (1); RCAF (1); LCx non-opacified | RCAS (1) |

| 5 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1); LCx non-opacified | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 6 | LCA extending LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 7 | LADF@ (1); LCxF (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 8 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 9 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 10 | No CAAs | RCAF (1) |

| 11 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 12 | LADF@ (1) | LADS (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 13 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF (multiple) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 14 | No CAAs | LCxS (multiple) |

| 15 | LADF (1) | LCxF (1) |

| 16 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 17 | LCAF (1); LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal RCA extended into distal segment |

| 18 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF@ (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 19 | LCA extending into LAD and LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (1) |

| 20 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 21 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 22 | LCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

| 23 | LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

n: number of coronary artery aneurysms; CAAs: coronary artery abnormalities; CTCA: CT coronary angiography; F: fusiform aneurysm; S: sacculr aneurysm; LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery; LCA: left main coronary artery; LCx: left circumflex coronary artery; RCA: right coronary artery; @: proximal coronary artery involvement with contiguous distal extension.

Abnormalities on CTCA in children with KD having distal coronary artery involvement

| Patient no. . | Details of aneurysms in proximal segments of coronary arteries (n) . | Details of aneurysms in distal segments of coronary arteries (n) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 2 | LCA extending into LADS (1) | RCAS (1) |

| 3 | LADF@ (1); LCxF@(1); RCAF (1) | LADS (1); RCAS (multiple); aneurysm in proximal LAD and LCx extended into distal segment |

| 4 | LCA extending into LADF (1); RCAF (1); LCx non-opacified | RCAS (1) |

| 5 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1); LCx non-opacified | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 6 | LCA extending LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 7 | LADF@ (1); LCxF (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 8 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 9 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 10 | No CAAs | RCAF (1) |

| 11 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 12 | LADF@ (1) | LADS (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 13 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF (multiple) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 14 | No CAAs | LCxS (multiple) |

| 15 | LADF (1) | LCxF (1) |

| 16 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 17 | LCAF (1); LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal RCA extended into distal segment |

| 18 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF@ (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 19 | LCA extending into LAD and LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (1) |

| 20 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 21 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 22 | LCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

| 23 | LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

| Patient no. . | Details of aneurysms in proximal segments of coronary arteries (n) . | Details of aneurysms in distal segments of coronary arteries (n) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 2 | LCA extending into LADS (1) | RCAS (1) |

| 3 | LADF@ (1); LCxF@(1); RCAF (1) | LADS (1); RCAS (multiple); aneurysm in proximal LAD and LCx extended into distal segment |

| 4 | LCA extending into LADF (1); RCAF (1); LCx non-opacified | RCAS (1) |

| 5 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1); LCx non-opacified | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 6 | LCA extending LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 7 | LADF@ (1); LCxF (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 8 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 9 | LADF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (3) |

| 10 | No CAAs | RCAF (1) |

| 11 | No CAAs | LADF (1) |

| 12 | LADF@ (1) | LADS (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 13 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF (multiple) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 14 | No CAAs | LCxS (multiple) |

| 15 | LADF (1) | LCxF (1) |

| 16 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 17 | LCAF (1); LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCA full-length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal RCA extended into distal segment |

| 18 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF@ (1); RCA full length aneurysm@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD, LCx and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 19 | LCA extending into LAD and LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | RCAF (1) |

| 20 | LCA extending into LAD@ and LCxF (1); RCAF@ (1) | RCAF (1); aneurysm in proximal LAD and RCA extended into distal segment |

| 21 | LCA extending into LADF@ (1) | Aneurysm in proximal LAD extended into distal segment |

| 22 | LCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

| 23 | LADF (1); LCxF (1); RCAF (1) | LADF (1) |

n: number of coronary artery aneurysms; CAAs: coronary artery abnormalities; CTCA: CT coronary angiography; F: fusiform aneurysm; S: sacculr aneurysm; LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery; LCA: left main coronary artery; LCx: left circumflex coronary artery; RCA: right coronary artery; @: proximal coronary artery involvement with contiguous distal extension.

Number of aneurysms

CTCA in these 23 patients revealed 60 aneurysms in coronary arteries. Of these, 37 were proximal (36 fusiform; 1 saccular) and 23 were distal (17 fusiform; 6 saccular). In addition, 11 patients with proximal aneurysm had a distal contiguous extension.

Location of distal CAAs

The location of distal CAAs was: right coronary artery (RCA) 15/23 patients; left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery 14/23 patients; left circumflex (LCx) coronary artery 4/23 patients.

Proximal coronary artery involvement with contiguous distal extension of aneurysms

In 11 patients there was distal contiguous extension of proximal CAAs. In these patients, 18 coronary arteries (LAD 10; RCA 6: LCx 2) showed distal extension of proximal CAAs (Fig. 1). Distal involvement of coronary arteries had not been detected on TTE in any of the patients.

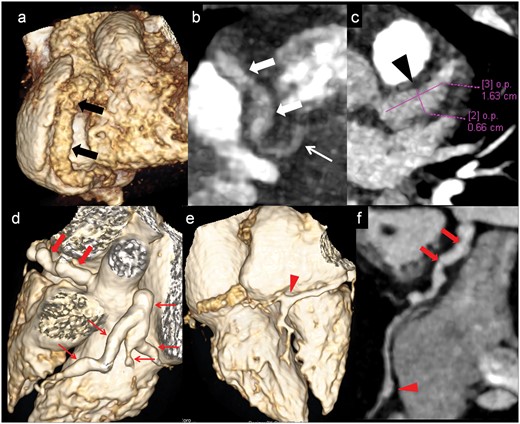

Proximal coronary artery with contiguous distal extension of aneurysms and branch vessels involvement

Patient no. 17: CTCA VR (a) and oblique coronal (b) images shows fusiform aneurysmaly dilated RCA in its entire course (proximal 8mm, mid 5.2mm, distal 4.2mm) (thick arrows in a and b). Note PDA is also dilated (thin arrow in b). CTCA axial image (c) shows fusiform aneurysm (6.6mmx16mm) in proximal LAD. (Patient no 6): CTCA VR images (d and e) and curved reformatted image of RCA (f) shows fusiform aneurysmaly dilated proximal and mid RCA (4.6mm) (thick arrows in e and f) with saccular aneurysm at distal RCA (3.5mm) at branching point (arrow head in e and f). LCA shows fusiform aneurysm (7.8mm) with extension into proximal and mid LAD, ramus intermedius and proximal LCx (thin arrows in d). CTCA: CT coronary angiography; VR: Volume rendered; RCA: right coronary artery; PDA: posterior descending artery; LAD: left anterior descending; LCx: left circumflex coronary artery.

Aneurysms in both proximal and distal segments but not in contiguity

Nine [9] patients (S. nos 1, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, 13, 20, 23) were found to have non-contiguous aneurysms in proximal and distal segments (Fig. 2 and supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online). In all these patients while aneurysms in proximal segments were detected on TTE, distal aneurysms had been missed.

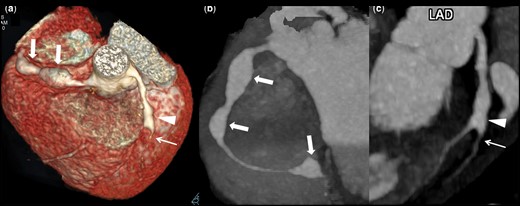

Aneurysms in proximal and distal segments but not in contiguity with branch vessels involvement and complications

Patient no 9: CTCA VR image (a) show non-contiguous fusiform aneurysms (8.5 mm) in proximal (5.5 mm) and mid (6 mm) RCA (thick arrows) along with fusiform aneurysm in proximal LAD (4 mm) involving origin of diagonal –1 branch (arrow head). Note stenosis distal to aneurysm (thin arrow). CTCA oblique coronal maximum intensity projection image of RCA (b) shows fusiform aneurysms in proximal, mid and distal (6 mm) RCA (thick arrows). CTCA curve reformatted image (c) demonstrates fusiform aneurysm in proximal LAD involving origin of diagonal –1 branch (arrow head) with stenosis distal to aneurysm (thin arrow). CTCA: CT coronary angiography; VR: volume rendered; RCA: right coronary artery; LAD: left anterior descending.

Distal involvement in presence of proximal involvement of some other coronary artery

Four patients (S. nos 2, 7, 15, 22) had distal CAAs (LAD 2; RCA 2; LCx 1) in the absence of proximal involvement (Fig. 3a and b and supplementary Fig. S2, available at Rheumatology online). For instance, patient no. 7 (during convalescent phase) had a fusiform aneurysm in mid-RCA (5.3 × 8.8 mm) with mural calcification (Fig. 3a and b). This had been missed on TTE carried out at the same time. This patient had a normal proximal segment of RCA but had proximal involvement in LAD and LCx (Table 1 and supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). Similarly, patient no 22 showed mid segment fusiform aneurysm (2.0 × 14 mm length) of LAD along with dilatation in LCA (supplementary Fig. S2, available at Rheumatology online).

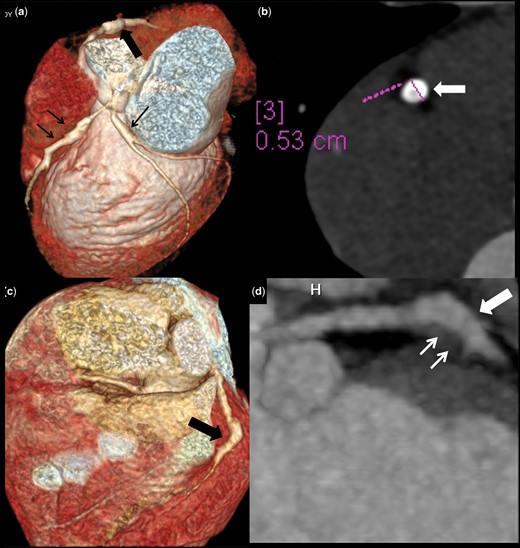

Distal CAA in presence of proximal involvement of some other coronary artery and complications

Patient no. 7: CTCA (convalescent phase) VR image (a) and axial image of RCA (b) shows fusiform aneurysm in mid RCA (5.3 mm) with mural calcifications (thick arrows in a and b). Note fusiform aneurysms in proximal LAD and proximal LCx (thin arrows). Patient no. 8: CTCA VR (c) image and oblique coronal reformatted image of LAD (d) shows fusiform aneurysm in mid LAD (8 mm) (thick arrows) with hypodense eccentric filling defect suggestive of thrombosis (3 mm) (thin arrows). CAA: coronary artery abnormalities; CTCA: CT coronary angiography; VR: volume rendered; RCA: right coronary artery; LAD: left anterior descending; LCx: left circumflex coronary artery.

Isolated distal involvement without involvement of any other coronary artery

Four patients (S. nos. 8, 10, 11, 14) had isolated distal CAAs in absence of any other coronary artery involvement (Fig. 4). For instance, patient no. 10 had a giant aneurysm in distal RCA (without discernible abnormality in proximal portion of any coronary artery) on CTCA that had been completely missed on TTE (Fig. 4a). In patient no. 14, CTCA was performed at 8 years of follow-up. It showed multiple saccular aneurysms in distal segments of obtuse marginal branch giving a ‘bunch of grapes’ appearance (Fig. 4b and c). TTE carried out during acute phase in this child had shown proximal LAD dilatation that had normalized on follow-up. In both of these patients (S. nos 10, 14) CTCA was performed in view of clinically severe disease during acute phase of disease.

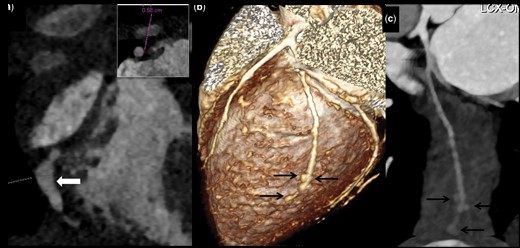

Isolated distal CAA without involvement of any other coronary artery

Patient no. 10: CTCA oblique coronal maximum intensity projection image shows fusiform aneurysm in distal RCA (arrow in a). Inset: axial image shows aneurysmally dilated RCA measuring 5.8 mm diameter. LAD and LCx were normal (not shown here). Patient no. 14: CTCA (convalescent phase) VR (b) and curved reformatted images of OM branch of LCx (c) shows few saccular aneurysms in distal most OM branch (arrows in b and c). CAA: coronary artery abnormalities; CTCA: CT coronary angiography; VR: volume rendered; RCA: right coronary artery; LAD: left anterior descending; LCx: left circumflex coronary artery; OM: obtuse marginal.

Branch vessel involvement

Five patients (S. nos 1, 2, 3, 9, 19) had extension of aneurysm in side branches of main coronary artery. These included: (i) LAD aneurysm extending into D1 branch of LAD (S. nos 1, 2, 9) (Fig. 2 and supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online); (ii) LAD aneurysm extending into both D1 and D2 branches of LAD (patient no. 3); (iii) complex fusiform aneurysm in RCA extending into conus branch and diagonal branch of LAD (patient no. 19); (iv) LCx aneurysm extending into obtuse marginal (patient no. 14) and diagonal (patient no. 19) branches in one each.

Nine patients (S. nos 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 13, 16, 17, 21) had aneurysms at branching point of distal RCA incorporating origins of posterior descending and posterolateral ventricular branches (Figs 1f and g, and 2, and supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online). Aneurysms at LCA bifurcation extending into LAD and LCx were seen in 10 patients (S. nos 2, 4, 5, 6, 13, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21) (Fig. 1e).

Complications in coronary artery aneurysms

Two patients (patient nos. 8, 21) showed intra-aneurysmal eccentric hypodense filling defect suggesting thrombus in LAD (Fig. 3d). One patient (patient no. 7) revealed mural calcifications (in mid segment of LAD and RCA) on follow-up CTCA performed 10 years after initial presentation (Fig. 3b). Patient no. 9 showed fusiform aneurysm in LAD that was extending into the D1 branch of LAD with stenosis of distal D1 branch (Fig. 2)—this had not been identified on TTE.

Discussion

KD is the most common vasculitis of childhood [1, 17, 18]. CAAs caused by KD may put children at risk for coronary artery events later in life. CAAs may persist and complicate with thrombus formation, remodelling, stenosis and mural calcifications mandating long-term follow-up [19, 20]. CAAs in patients with KD are usually seen in proximal segments of coronary arteries. TTE has conventionally been considered the standard of care for imaging of coronary arteries both at presentation and on follow-up. However, with application of imaging modalities such as CCA, CTCA and MRCA, it is now clear that KD may affect mid and distal segments of coronary arteries as well [13, 14, 21]. TTE is of limited value for assessment of these segments. Moreover, TTE has other limitations as well, including operator dependency, inter-observer variability and poor acoustic window in older children [22].

CCA is the gold standard for imaging of coronary arteries; however, it is invasive, requires sedation/anaesthesia in young children, is associated with inordinate radiation exposure and cannot be repeated often. Moreover it fails to detect mural abnormalities [6, 9]. Therefore, there is a need for an imaging modality that can circumvent the problems associated with both TTE and CCA. Cross-sectional imaging modalities (e.g. CTCA and MRCA) have recently been used for assessment of CAAs in KD. Tsuji et al. have compared CTCA with CCA in measuring coronary artery diameters and found significant correlation between these techniques [23]. In a study by Wu et al. CTCA also visualized two distal small aneurysms better than CCA [24]. MRCA has also been recently developed as a sensitive modality for diagnosis of CAAs in patients with KD. However, CTCA scores over MRCA as it has higher spatial and temporal resolution, much shorter scanning time and better image quality [6, 9, 25, 26]. Kim et al. have compared CTCA and MRCA for detection of CAAs in patients with KD. It was found that CTCA was better than MRCA in per-segment analysis and distal segment evaluation [27]. CTCA, therefore, has now emerged as a robust imaging modality for KD. It allows comprehensive evaluation of both proximal as well as distal segments of all coronary arteries [28].

The limiting factor hitherto in more widespread use of CTCA in KD was high radiation exposure. As a result, its application in children was rather limited. However, with availability of higher slice CT platforms (128, 256 and 384 slice) and DSCT scanners, it is now possible to acquire high resolution and motion-free images at all heart rates and with radiation exposures well below 1 mSv [6, 14, 26]. CTCA provides explicit details of coronary arteries along the entire course, including branches. It also clearly delineates luminal calibre and intramural changes. Moreover, it can be repeated on follow-up as it is non-invasive. CTCA is especially useful in older children and adolescents, who often have a poor acoustic window for TTE.

There is paucity of literature on involvement of distal coronary arteries in children with KD. Chu et al. in their study on six patients showed that CTCA identified one saccular aneurysm at junction of distal RCA and posterior descending artery, which was not detected by TTE [21]. Chao et al. have reported CTCA and TTE findings of 16 patients with KD [29]. CTCA identified two additional CAAs that had been missed on TTE. These were present in middle and distal segments. In both these patients, TTE was negative for any CAAs even in proximal segment. Recently, Dimitriades et al. in their study of 70 patients have also shown that TTE is prone to miss CAAs in distal segments [14]. Authors did not find isolated CAAs in distal segments without proximal involvement; however, in some children diameters of distal segment exceeded the diameter of proximal CAAs thereby resulting in change in categorization of CAAs. The present study is the largest on the subject (supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online), and gives a detailed iteration of distal segments of all coronary arteries.

We have shown that amongst 176 patients with KD who underwent CTCA, 23 had distal CAAs (RCA 15/23; LAD 14/23; LCx 4/23patients). Distal extension of proximal coronary artery aneurysm was identified in 11 patients that had been missed on TTE. Nine patients showed non-contiguous aneurysm in both proximal and distal segments. Four patients showed distal segment aneurysms in absence of proximal involvement of the same coronary artery, but with involvement of some other coronary artery. Four patients had isolated distal CAAs in the absence of any other coronary involvement. CTCA also identified complications such as thrombosis, mural calcification and stenosis. These were completely missed on TTE. Our study shows that CAAs can, at times, occur in distal segments in isolation and also in association or extension of proximal CAAs. We have shown that CTCA is a much better imaging modality than TTE for evaluation of distal CAAs in patients with KD. We have also shown that distal CAAs are not uncommon in KD, and isolated distal CAAs can also occur. These can impact treatment planning decisions.

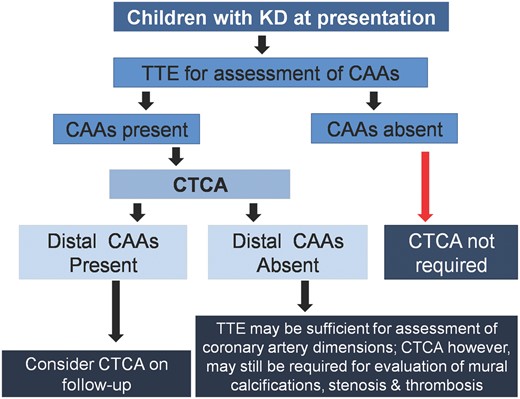

Based on our experience over 8 years, we are of the considered opinion that all children with KD who have CAAs on TTE should be offered CTCA (Fig. 5). This is important because many children may have distal CAAs that are usually missed on TTE. Results of CTCA would impact management and follow-up strategies of affected patients with KD. However, published literature on this aspect is scarce and not everyone would agree with our proffered viewpoint.

Proposed algorithm for use of CTCA in children with KD

KD: Kawasaki disease; CAA: coronary artery abnormalities: CTCA: CT coronary angiography; TTE: 2D transthoracic echocardiography.

We have shown that under expert hands, CTCA can be carried out even in small infants and requires only mild sedation. We can now perform CTCA at radiation exposure <1 mSV. Our is a federally funded tertiary level teaching institute and the incurred costs for CTCA in our setup are minimal, ≈2500–3000 INR (≈25–30 Pound Sterling; ≈30–36 Euros). The procedure is very safe and we have not encountered any reactions to the injected non-ionic contrast.

One limitation of our study is that over the years TTE had been performed by different operators having variable experience and expertise. It is possible that this may have impacted findings on TTE [22]. However, changes in care providers are inevitable in any clinical service.

To conclude, CTCA, if done on current generation higher detector and DSCT scanners with radiation optimization techniques, allows explicit evaluation of coronary arteries along the entire course, including branches. CTCA demonstrates CAAs in distal segments of coronary arteries in a significant number of children with KD—these cannot be detected on TTE. There is, as yet, no consensus on the indications for CTCA in children with KD. We thus propose that CTCA be considered as a complimentary imaging modality in selected children with KD who have CAAs on TTE. Presence of distal CAAs on CTCA requires follow-up CTCA for treatment planning. If distal CAAs are not detected on CTCA, children may be followed by TTE but CTCA may still be required for delineation of complications (thrombus, stenosis and mural calcifications) in segments affected during acute stage (Fig. 5).

Funding: No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article are available in the manuscript, in online supplementary material and in our records. These data can be shared on request.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

Author notes

Manphool Singhal and Rakesh Kumar Pilania contributed equally and share first authorship.

Comments