-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Puja Mehta, Rachel K Hoyles, Harsha Gunawardena, Bibek Gooptu, Nazia Chaudhuri, Melissa J Heightmann, Helen Garthwaite, Henry Penn, Arnab Datta, Shahir Hamdulay, Boris Lams, Sangita Agarwal, Melissa Wickremesinghe, Gisli Jenkins, Joanna C Porter, Christopher P Denton, Rheumatologists have an important role in the management of interstitial lung disease (ILD): a cross-speciality, multi-centre, UK perspective, Rheumatology, Volume 61, Issue 5, May 2022, Pages 1748–1751, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keac061

Close - Share Icon Share

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) refers to a heterogeneous and challenging group of diffuse parenchymal lung disorders. ILD, including progressive fibrosing ILD, is a common manifestation of systemic autoimmune CTD and is a leading cause of mortality in many rheumatic conditions [1]. ILD is most frequent in SSc, idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and RA, but may also manifest in patients with SS and SLE. The research term interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features was defined in 2015 to classify patients with ILD that may demonstrate clinical, radiological or serological characteristics of CTD, but do not meet formal CTD definitions [2]. However, the value and prognostic relevance of these classification criteria are currently unclear, may reflect limitations of our current rheumatological CTD criteria and demonstrate a growing need for cross-speciality collaboration between rheumatologists and respiratory physicians in ILD clinical practice and research. Respiratory Society guidelines [3, 4] and NHS England commissioning services [5] recommend a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to diagnosis and management of ILD, involving clinical (including respiratory and rheumatology input), radiological and (when indicated) histopathological involvement. Strategies for managing SSc-ILD have considerably advanced in recent years, a testament to dedicated and concerted cross-specialty collaboration; however, progress in other autoimmune ILDs has been slow. Here, as a collective of rheumatologists and respiratory physicians, we describe the important and expanding role of rheumatologists in the management of ILD (Fig. 1) and outline strategies to improve collaborative working and therefore outcomes in patients with ILD.

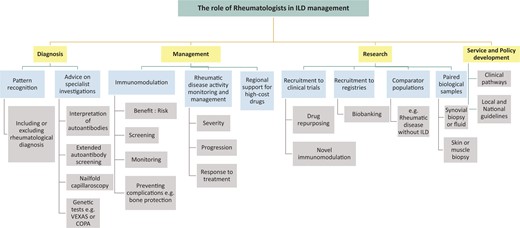

The role of rheumatologists in the management of patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD)

Despite improvement, there remains considerable need to develop better communication and shared learning between rheumatologists and respiratory physicians. One example of shared decision-making is the now debunked issue of MTX-induced ILD. Despite a sufficient body of evidence to assuage concerns regarding fibrotic ILD [6], some reticence and unease remains among clinicians in both fields. Other areas of controversy and often debated among clinicians include the use of MTX for articular disease in patients with concurrent ILD and the rare, but recognized MTX-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The confusion is not limited to MTX. Lung disease in RA is poorly understood, despite it being recognized as prevalent and important, with considerable impact on prognosis, survival and therapeutic approach. The diagnosis of ILD in patients with RA and whether this is disease-related or drug-related is central to consistent and effective approaches to management.

There is an urgent need for a systematic approach, with a firm evidence base, to optimize diagnosis, management and service provision for patients with autoimmune ILD. Cross-specialty collaborative working models are increasingly being used, particularly with ILD radiology MDT meetings, attended by respiratory physicians and rheumatologists, to discuss complex clinical cases. However, the infrastructure and format are not standardized. For best practice it is important that the value and advantages of joint working are evaluated and recognized and that appropriate administrative support is provided to encourage high quality MDT discussions and outputs. MDTs should be widely incorporated into service specifications and consultant job plans rather than being irregular or convened ad-hoc. There are many other models for cross-specialty working beyond the MDT meeting, including combined clinics (where patients are reviewed at the same visit by both specialties) or hybrid models including combined or multi-speciality clinics (e.g. sarcoidosis or SSc models) where patients are seen independently, but physicians are available for advice and discussion if needed; this can be especially valuable for the differential diagnosis of complex cases and for refining or changing drug treatment relevant to both specialties.

Pulmonary manifestations may pre-date the onset of other manifestations of CTD or associated features may be subtle at presentation (e.g. in early SSc) or absent (e.g. amyopathy in anti-synthetase syndromes). Rheumatologists are experienced in pattern recognition across the spectrum of multisystem pathologies to detect forme-frustes or occult CTD (e.g. SSc sine scleroderma), detection and follow-up of early ILD, as well as being able to weigh up the relevance of subjective symptoms, e.g. RP, fatigue, hair loss. In addition, they provide expertise in evaluating the clinical significance of autoantibody screening in CTD-ILD, including robust interpretation of anti-nuclear patterns, and correlation with extended serological panels. Rheumatologists are also well placed to advise on and access specialist investigations such as nailfold capillaroscopy and genetic tests for emerging rare diseases bridging rheumatology and respiratory medicine, e.g. VEXAS syndrome [7] in adults or COPA syndrome [8] in children or adolescents.

The distinction of fibrotic from inflammatory ILD, based on clinical context, radiological and sometimes cytological/histological findings, may have significant implications for therapy. For example, anti-fibrotics may be indicated to slow disease progression in progressive fibrosing ILD, as per recent NICE guidelines in the UK [9]. It is currently unclear whether immunomodulation (with/without antifibrotics in the future) may lead to stability or some improvement in lung function in inflammatory autoimmune ILD. Inappropriate prescribing may result in suboptimal or ineffective treatment of lung pathology and may also expose patients to harm and adverse events such as diarrhoea secondary to nintedanib (anti-fibrotic) or infection with immunosuppression. Rheumatologists can play a key role in helping to diagnose and differentiate autoimmune ILD from other forms of ILD, an important and often challenging distinction that may shift the balance in favour of a trial of immunomodulatory therapy.

Management of autoimmune ILD should involve shared decision-making between rheumatology and respiratory physicians and is often a careful balance prioritizing differential organ involvement. Respiratory physicians have greater expertise with anti-fibrotics and rheumatologists have an important role in managing systemic and extra-pulmonary manifestations of CTD and have wide expertise in using immunomodulation, critical for benefit: risk evaluations to optimize drug selection. Treatments may have different efficacy across disease compartments; for example, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide may be effective for lung disease but less beneficial for articular inflammation. Rheumatologists are familiar with guidance for screening, monitoring (e.g. optical coherence tomography testing for hydroxycholoroquine-induced maculopathy), preventing and managing iatrogenic complications, such as glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis including bisphosphonate drug holidays to reduce risks of atypical femoral fractures. Reflux and micro-aspiration represent a further management challenge, as this may exacerbate ILD and may be worsened by both bisphosphonates and glucocorticoids. Rheumatologists are well-versed in the nuances of drug safety alerts (e.g. controversies surrounding thrombotic events with JAK inhibitors [10]). Both rheumatologists and respiratory physicians have established pathways for prescription and supply of high-cost drugs including biologics and anti-fibrotics, respectively, and work in multi-disciplinary teams with clinical nurse specialists, physiotherapists and psychologists who are experienced in counselling, consenting, monitoring (e.g. using specialist software programmes) and supporting patients albeit with an emphasis on different monitoring systems and medications. Rheumatology teams are able to advise on immunomodulation and administering drugs in dedicated infusion suites, and respiratory teams are trained in monitoring lung function, and physiology to modify treatments accordingly. Furthermore, both respiratory physicians and rheumatologists have established links with other specialists who may be required in the management of patients with CTD-ILD, such as cardiologists, for management of pulmonary hypertension, and obstetricians for higher risk pregnancies.

Rheumatology-respiratory collaboration has been critical to successful randomized controlled trials such as those that led to the licensing of tocilizumab in SScl-ILD and studies that provided preliminary evidence for antifibrotics in autoimmune ILD [11]. Although there has been some progress in understanding the mechanistic basis for autoimmune ILD [e.g. the discovery of the shared genetic risk factor (MUC5B promoter variant rs35705950 mutation) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated ILD and IPF [12]], there remains a considerable unmet need for effective therapies, better understanding of the aetiopathogenesis, and identification of biomarkers to predict treatment response and prognosis, to enable a stratified and ultimately precision medicine treatment approach. Prospective research and comprehensive data capture, with deep phenotyping and biobanking, is vital, with international multicentre registries and controlled trials (either of repurposed or novel drugs). Multidisciplinary research is necessary to optimize clinical trial design outcomes as well as addressing mechanistic questions regarding the aetiopathogenesis of ILD. For example, leveraging both specialities’ prior experience and expertise in the acquisition and analysis of paired biological samples, such as the site of disease, such as ILD via bronchoscopy and arthritis via synovial biopsy or fluid. Triangulating data from autoimmune ILD with published datasets from other lung diseases such as IPF will be invaluable to uncover pathomechanisms. This will facilitate the generation of evidence-based, validated guidelines to improve the clinical and research outcomes for patients with autoimmune ILD, which will only be possible through the pooling resources and collective effort and intelligence of both specialities.

As more treatment options emerge and there is greater appreciation of the frequency and significance of ILD in rheumatic disease, there is a pressing need to improve management and outcome for patients with autoimmune ILD. Robust and effective links between rheumatology and respiratory medicine are imperative to optimize diagnosis, management, research efforts and service and policy development.

Funding: No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: P.M. is a Medical Research Council (MRC)-GlaxoSmithKline EMINENT clinical training fellow with project funding outside of the submitted work; and receives co-funding by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) University College London Hospitals (UCLH) Biomedical Research Centre. P.M. reports consultancy fees from SOBI, Abbvie and Lilly outside of the submitted work. R.K.H. reports speaking and consultancy fees for Boehringer-Ingelheim. H.G. reports speaking and consultancy fees for Boehringer-Ingelheim. G.J. reports a commercial Contract with PatientMPower, grants or contracts with AstraZeneca, Biogen, Galecto, GlaxoSmithKline, RedX, Piliant, consultancy fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Veractye, resolution therapeutics, Piliant, Speakers fees from Chiesi, Roche, PatientMPower and Astrazeneca, DSMB involvement for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Galapagos, Vicore, Board role for NuMedii and other financial/non-financial interest with Action for Pulmonary Fibrosis. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

NHS England. Interstitial Lung Disease (Adults) Service Specification,

[TA747] Tag. Nintedanib for treating progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA747 (10 December

Comments