-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Renaud Felten, Margherita Giannini, Benoit Nespola, Beatrice Lannes, Dan Levy, Raphaele Seror, Olivier Vittecoq, Eric Hachulla, Aleth Perdriger, Philippe Dieude, Jean-Jacques Dubost, Anne-Laure Fauchais, Veronique Le Guern, Claire Larroche, Emmanuelle Dernis, Dewi Guellec, Divi Cornec, Jean Sibilia, Xavier Mariette, Jacques-Eric Gottenberg, Alain Meyer, Refining myositis associated with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: data from the prospective cohort ASSESS, Rheumatology, Volume 60, Issue 2, February 2021, Pages 675–681, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa257

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To refine the prevalence, characteristics and response to treatment of myositis in primary SS (pSS).

The multicentre prospective Assessment of Systemic Signs and Evolution in Sjögren’s Syndrome (ASSESS) cohort of 395 pSS patients with ≥60 months’ follow-up was screened by the 2017 EULAR/ACR criteria for myositis. Extra-muscular complications, disease activity and patient-reported scores were analysed.

Before enrolment and during the 5-year follow-up, myositis was suspected in 38 pSS patients and confirmed in 4 [1.0% (95% CI: 0.40, 2.6)]. Patients with suspected but not confirmed myositis had higher patient-reported scores and more frequent articular and peripheral nervous involvement than others. By contrast, disease duration in patients with confirmed myositis was 3-fold longer than without myositis. Two of the four myositis patients fulfilled criteria for sporadic IBM. Despite receiving three or more lines of treatment, they showed no muscle improvement, which further supported the sporadic IBM diagnosis. The two other patients did not feature characteristics of a myositis subtype, which suggested ‘pure’ pSS myositis. Steroids plus MTX was then efficient in achieving remission.

Myositis, frequently suspected, occurs in 1% of pSS patients. Especially when there is resistance to treatment, sporadic IBM should be considered and might be regarded as a late complication of this disease.

Myositis was suspected in 10% of the cohort, featuring frequent painful extra-muscular involvements and higher patient-reported scores.

Myositis was diagnosed in 1.0% of the patients, with 3-fold longer disease duration than their counterparts.

The spectrum of myositis in primary SS has been significantly refined, and sporadic IBM is suggested as a late complication of primary SS.

Introduction

Primary SS (pSS) is a systemic disorder primarily characterized by lymphocytic infiltration and functional impairment of exocrine glands. However, the autoimmune process can potentially affect any organ.

Myositis is a rare condition, characterized by myopathy with evidence of inflammatory-driven muscle lesions. It encompasses a heterogeneous group of diseases. Myositis has been reported in pSS, with great variation in prevalence (0.85–14%) and characteristics [1–4], probably because of heterogeneous definitions from cross-sectional studies with heterogeneous clinical assessment of patients. Hence, its significance is currently unclear.

On one hand, myositis is considered a systemic manifestation of pSS, with important consequences for management because muscle involvement has the greatest weight in the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) [5]. However, the few studies regarding its treatment in pSS patients have reported heterogeneous therapeutic strategies and inconsistent response to treatments [6].

On the other hand, several myositis subgroups have recently been defined on the basis of clinical, serological and histopathological characteristics [7]. Their identification is fundamental because each of these distinct disorders requires its own management. Yet, these conditions have not been systematically recognized in previous works. In particular, in a recent report 18% of patients with myositis attributed to pSS had anti-Jo1 antibodies [4], the most frequent serological marker of anti-synthetase syndrome, a life-threatening condition requiring rapid immunomodulatory treatment. Another report described 0.6% of pSS patients meeting the criteria of sporadic IBM (sIBM) [3], an under-diagnosed condition in which immunomodulating agents are, in contrast, not effective and may even increase the risk of progression toward handicap.

In light of recent diagnostic tools for myositis, in this study, we aimed to refine the prevalence, characteristics and response to treatment of myositis in a large multicentre prospective cohort of pSS with >60 months’ follow-up.

Methods

Patient population

Between 2006 and 2009, 395 consecutive patients with pSS were recruited in a French nationwide multicentre prospective cohort, the Assessment of Systemic Signs and Evolution in Sjögren’s Syndrome (ASSESS) cohort. Inclusion criteria were pSS according to revised American-European criteria and age ≥18 years [8]. During a 5-year follow-up, data were collected by case-report file tracked on a centralized computer database after monitoring. The ASSESS study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bichat Hospital. All patients gave their informed written consent to be in the study. All patients fulfilled the American-European Consensus Group criteria for pSS.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Myositis diagnosis

Potential myositis was systematically recorded before enrolment, at enrolment and every year thereafter prospectively based on muscular pain, weakness and/or elevated serum muscle enzyme level (creatinine kinase). Myositis diagnosis was further defined by 2017 EULAR/ACR criteria for myositis [7]. These validated criteria take into account age of onset, muscle weakness, skin manifestations, serum muscle enzyme level, anti-Jo1 antibody positivity and muscle biopsy features. Importantly, EULAR/ACR criteria can be applied to myositis patients with overlap diagnoses, and patients with SS (with and without myositis) were included in the cohorts on which these classification criteria were built.

Charts of all patients with suspected myositis (muscular pain, weakness and/or elevated serum muscle enzyme level) were systematically reviewed. All muscle biopsies, performed for diagnosis purposes, were systematically reviewed by the same expert pathologist who is specialized in myositis and is from a national reference centre for rare systemic autoimmune diseases. Characterization of muscle infiltrate was performed by immunohistochemical staining using anti-CD20 (clone L26, DAKO), anti-CD4 (clone SP35, VENTANA) and anti-CD8 (clone C8/144B, DAKO) antibodies. The presence of the following auto-antibodies associated with inflammatory myopathies was analysed in patients’ baseline serum in a central laboratory: anti-cN1A (EuroImmun, Lübeck, Germany), -HMGCR, -AMA2, -Mi-2, -MDA5, -NXP2, -TIF-1γ, -SAE (D-TEK, Mons, Belgium), -SRP, -Jo1, -PL7, -PL12, -EJ, -OJ, -KS, -Zo, -Ha, -U1-RNP, -Ku and -PM/Scl antibodies (Alphadia, Wavre, Belgium). The presence of criteria for myositis and subgroups [9–12] was systematically tested. Treatment efficacy was recorded.

Extra-muscular assessments

Extra-muscular systemic complications of pSS and their activity were assessed by the ESSDAI. This validated quantitative score is based on systemic features assessed in 12 organ-specific domains including a muscular one [5]. For comparison between groups, we used the ESSDAI score without taking into account this muscular domain.

The EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Related Index (ESSPRI), a multinational validated patient-reported outcome measure evaluating dryness, fatigue and pain on a visual analogue scale (0–10), was completed by all patients each year.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as median (range) or frequency (%) with 95% CIs. Normality was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables between groups were compared by Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, Wilcoxon test, Fisher test, Kruskall–Wallis one-way analysis of variance or χ2 test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. Clinical features associated with P < 0.10 on univariate analysis were included in a multivariate linear regression model assessing factors associated with myositis. All analyses were performed with JMP v7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability statement

All individual de-identified participant data can be shared on demand.

Results

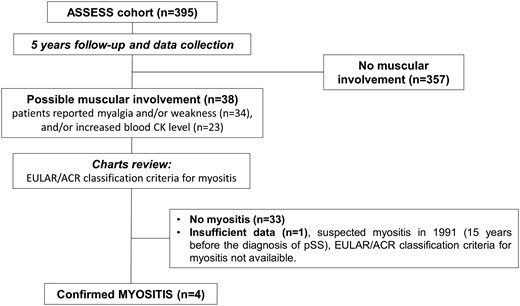

Before enrolment and during the 5-year follow-up, myositis was suspected in 38 pSS patients, most frequently because patients reported muscular pain or weakness (n = 34), and/or elevated serum muscle enzyme level (n = 23) (Fig. 1). Only six patients with suspected muscle involvement showed weakness at physician examination. On further analysis of 2017 EULAR/ACR criteria in the 38 patients, myositis was revealed in only 4 cases. Among the 38 patients, measurement of nerve conduction and electromyography were performed in 15 patients, muscular MRI was performed in 3 patients and muscle biopsy in 8 patients. Other final diagnoses were articular involvement (n = 26), polyneuropathy (n = 12), fibromyalgia (n = 3), multinevritis related to vasculitis (n = 4), post-trauma rhabdomyolysis (n = 1), physiological exercise-increased serum muscle enzyme level (n = 1), and myalgia (n = 2) and/or elevated serum muscle enzyme level (n = 3, range 361–837 UI/l) without any other cause than pSS (n = 4). Thus, prevalence of myositis at last follow-up was 1.0/100 patients (95% CI: 0.40, 2.6).

Flow of patients with pSS in the study

pSS: primary SS; AECG: American-European Consensus Group.

Comparison of the patients (i) with myositis, (ii) with suspected but not confirmed myositis and (iii) without suspicion of muscle involvement is shown in Table 1. Patients with suspected but not confirmed myositis had higher mean ESSPRI than the other two groups at baseline (P = 0.024) and over the 5-year follow-up (P = 0.05). In addition, 76.5% (n = 26) of patients with suspected myositis had articular involvement, which was more frequent than in the other groups (31.4% for patients without myositis and 50% for patients with confirmed myositis; P < 0.0001). Finally, 35.3% (n = 12) of patients with suspected myositis had peripheral nervous system involvement, which was also more frequent than in patients without myositis (10.9%) or with confirmed myositis (none) (P = 0.0002). Among the seven patients with peripheral nervous system involvement before or at inclusion, 57.1% had pure sensory neuropathy and 42.9% sensorimotor neuropathy. Their other characteristics were similar to the group without suspected muscle involvement.

Characteristics of patients with pSS: none, suspected and confirmed myositis according to ESSDAI

| . | None (n=357) . | Suspected but not confirmed (n=34) . | Confirmed (n=4) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis (P-value) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at pSS diagnosis (years) | 53 (17–82) | 51 (24–77) | 42 (39–48) | 0.20 | – |

| Female | 331/354 (93.5%) | 33/34 (97.1%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| Disease duration (years) | 5.0 (0.0–30.0) | 5.0 (0.0–26.0) | 15.0 (8.0–32.0) | 0.036a,c | 0.072 |

| Patient-reported measures | |||||

| Baseline ESSPRI score | 5.3 (0.0–10.0) | 6.7 (1.7–9.0) | 5.5 (4.7–8.7) | 0.024c | 0.39 |

| Dryness VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 0.06 | – |

| Fatigue VAS (0–10) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (2.0–10.0) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) | 0.17 | – |

| Pain VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–9.0) | 4.5 (3.0–8.0) | 0.08c | – |

| Mean ESSPRI score during follow-up | 5.7 (0–9.7) | 7.2 (2.3–9.1) | 5.9 (5.7–5.9) | 0.05 | – |

| Clinical systemic involvement (ever) | 253/357 (70.9%) | 26/34 (76.5%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.77 | – |

| Domain of the ESSDAI (ever during follow-up) | |||||

| Constitutional | 28 (7.8%) | 6 (17.7%) | 0 | 0.12 | – |

| Lymphadenopathy | 20 (5.6%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| Glandular | 72 (20.2%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.12 | – |

| Articular | 112 (31.4%) | 26 (76.5%) | 2 (50.0%) | <0.0001c | 0.0001 |

| Cutaneous | 37 (10.4%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0 | 0.58 | – |

| Pulmonary | 85 (23.8%) | 8 (23.5%) | 1 (25.0%) | 1.00 | – |

| Renal | 14 (3.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| PNS | 39 (10.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | 0 | 0.0002c | 0.0108 |

| CNS | 9 (2.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.94 | – |

| Haematological | 127 (16.5%) | 12 (32.4%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.91 | – |

| Biological | 347 (97.2%) | 33 (97.1%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.94 | – |

| Baseline ESSDAI score without muscular domain | 3 (0–25) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–12) | 0.81 | – |

| Mean ESSDAI score without muscular domain during follow-up | 3 (0–24) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–8) | 0.71 | – |

| Associated fibromyalgia (n=101) | 27/93 | 3/7 | 0/1 | 0.60 | – |

| Lymphoma (ever) | 17/357 (4.8%) | 0/34 | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Baseline biology | |||||

| Anti-SSA antibodies | 207/348 (59.5%) | 18/33 (54.6%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.93 | – |

| Anti-SSB antibodies | 123/348 (34.5%) | 5/33 (14.7%) | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| RF | 82/337 (24.3%) | 5/31 (16.1%) | 0/4 | 0.32 | – |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 36/298 (12.1%) | 2/34 (5.9%) | 0/4 | 0.45 | – |

| CK (U/l) | 75 (22–412) | 149 (31–2208) | 147 (88–291) | <0.0001a,c | – |

| Number of treatments (besides steroids) | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) | 3 (1–4) | 0.0029a,b,c | – |

| . | None (n=357) . | Suspected but not confirmed (n=34) . | Confirmed (n=4) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis (P-value) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at pSS diagnosis (years) | 53 (17–82) | 51 (24–77) | 42 (39–48) | 0.20 | – |

| Female | 331/354 (93.5%) | 33/34 (97.1%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| Disease duration (years) | 5.0 (0.0–30.0) | 5.0 (0.0–26.0) | 15.0 (8.0–32.0) | 0.036a,c | 0.072 |

| Patient-reported measures | |||||

| Baseline ESSPRI score | 5.3 (0.0–10.0) | 6.7 (1.7–9.0) | 5.5 (4.7–8.7) | 0.024c | 0.39 |

| Dryness VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 0.06 | – |

| Fatigue VAS (0–10) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (2.0–10.0) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) | 0.17 | – |

| Pain VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–9.0) | 4.5 (3.0–8.0) | 0.08c | – |

| Mean ESSPRI score during follow-up | 5.7 (0–9.7) | 7.2 (2.3–9.1) | 5.9 (5.7–5.9) | 0.05 | – |

| Clinical systemic involvement (ever) | 253/357 (70.9%) | 26/34 (76.5%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.77 | – |

| Domain of the ESSDAI (ever during follow-up) | |||||

| Constitutional | 28 (7.8%) | 6 (17.7%) | 0 | 0.12 | – |

| Lymphadenopathy | 20 (5.6%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| Glandular | 72 (20.2%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.12 | – |

| Articular | 112 (31.4%) | 26 (76.5%) | 2 (50.0%) | <0.0001c | 0.0001 |

| Cutaneous | 37 (10.4%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0 | 0.58 | – |

| Pulmonary | 85 (23.8%) | 8 (23.5%) | 1 (25.0%) | 1.00 | – |

| Renal | 14 (3.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| PNS | 39 (10.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | 0 | 0.0002c | 0.0108 |

| CNS | 9 (2.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.94 | – |

| Haematological | 127 (16.5%) | 12 (32.4%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.91 | – |

| Biological | 347 (97.2%) | 33 (97.1%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.94 | – |

| Baseline ESSDAI score without muscular domain | 3 (0–25) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–12) | 0.81 | – |

| Mean ESSDAI score without muscular domain during follow-up | 3 (0–24) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–8) | 0.71 | – |

| Associated fibromyalgia (n=101) | 27/93 | 3/7 | 0/1 | 0.60 | – |

| Lymphoma (ever) | 17/357 (4.8%) | 0/34 | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Baseline biology | |||||

| Anti-SSA antibodies | 207/348 (59.5%) | 18/33 (54.6%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.93 | – |

| Anti-SSB antibodies | 123/348 (34.5%) | 5/33 (14.7%) | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| RF | 82/337 (24.3%) | 5/31 (16.1%) | 0/4 | 0.32 | – |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 36/298 (12.1%) | 2/34 (5.9%) | 0/4 | 0.45 | – |

| CK (U/l) | 75 (22–412) | 149 (31–2208) | 147 (88–291) | <0.0001a,c | – |

| Number of treatments (besides steroids) | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) | 3 (1–4) | 0.0029a,b,c | – |

Data are median (range) unless indicated. a,b,cP < 0.05 comparing confirmed myositis vs no myositis (a), confirmed myositis vs suspected myositis (b) and suspected myositis vs no myositis (c). VAS: visual analogue scale; PNS: peripheral nervous system; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; ESSPRI: EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Related Index; CK: creatinine kinase.

Characteristics of patients with pSS: none, suspected and confirmed myositis according to ESSDAI

| . | None (n=357) . | Suspected but not confirmed (n=34) . | Confirmed (n=4) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis (P-value) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at pSS diagnosis (years) | 53 (17–82) | 51 (24–77) | 42 (39–48) | 0.20 | – |

| Female | 331/354 (93.5%) | 33/34 (97.1%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| Disease duration (years) | 5.0 (0.0–30.0) | 5.0 (0.0–26.0) | 15.0 (8.0–32.0) | 0.036a,c | 0.072 |

| Patient-reported measures | |||||

| Baseline ESSPRI score | 5.3 (0.0–10.0) | 6.7 (1.7–9.0) | 5.5 (4.7–8.7) | 0.024c | 0.39 |

| Dryness VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 0.06 | – |

| Fatigue VAS (0–10) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (2.0–10.0) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) | 0.17 | – |

| Pain VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–9.0) | 4.5 (3.0–8.0) | 0.08c | – |

| Mean ESSPRI score during follow-up | 5.7 (0–9.7) | 7.2 (2.3–9.1) | 5.9 (5.7–5.9) | 0.05 | – |

| Clinical systemic involvement (ever) | 253/357 (70.9%) | 26/34 (76.5%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.77 | – |

| Domain of the ESSDAI (ever during follow-up) | |||||

| Constitutional | 28 (7.8%) | 6 (17.7%) | 0 | 0.12 | – |

| Lymphadenopathy | 20 (5.6%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| Glandular | 72 (20.2%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.12 | – |

| Articular | 112 (31.4%) | 26 (76.5%) | 2 (50.0%) | <0.0001c | 0.0001 |

| Cutaneous | 37 (10.4%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0 | 0.58 | – |

| Pulmonary | 85 (23.8%) | 8 (23.5%) | 1 (25.0%) | 1.00 | – |

| Renal | 14 (3.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| PNS | 39 (10.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | 0 | 0.0002c | 0.0108 |

| CNS | 9 (2.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.94 | – |

| Haematological | 127 (16.5%) | 12 (32.4%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.91 | – |

| Biological | 347 (97.2%) | 33 (97.1%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.94 | – |

| Baseline ESSDAI score without muscular domain | 3 (0–25) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–12) | 0.81 | – |

| Mean ESSDAI score without muscular domain during follow-up | 3 (0–24) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–8) | 0.71 | – |

| Associated fibromyalgia (n=101) | 27/93 | 3/7 | 0/1 | 0.60 | – |

| Lymphoma (ever) | 17/357 (4.8%) | 0/34 | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Baseline biology | |||||

| Anti-SSA antibodies | 207/348 (59.5%) | 18/33 (54.6%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.93 | – |

| Anti-SSB antibodies | 123/348 (34.5%) | 5/33 (14.7%) | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| RF | 82/337 (24.3%) | 5/31 (16.1%) | 0/4 | 0.32 | – |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 36/298 (12.1%) | 2/34 (5.9%) | 0/4 | 0.45 | – |

| CK (U/l) | 75 (22–412) | 149 (31–2208) | 147 (88–291) | <0.0001a,c | – |

| Number of treatments (besides steroids) | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) | 3 (1–4) | 0.0029a,b,c | – |

| . | None (n=357) . | Suspected but not confirmed (n=34) . | Confirmed (n=4) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis (P-value) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at pSS diagnosis (years) | 53 (17–82) | 51 (24–77) | 42 (39–48) | 0.20 | – |

| Female | 331/354 (93.5%) | 33/34 (97.1%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| Disease duration (years) | 5.0 (0.0–30.0) | 5.0 (0.0–26.0) | 15.0 (8.0–32.0) | 0.036a,c | 0.072 |

| Patient-reported measures | |||||

| Baseline ESSPRI score | 5.3 (0.0–10.0) | 6.7 (1.7–9.0) | 5.5 (4.7–8.7) | 0.024c | 0.39 |

| Dryness VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 0.06 | – |

| Fatigue VAS (0–10) | 6.0 (0.0–10.0) | 7.0 (2.0–10.0) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) | 0.17 | – |

| Pain VAS (0–10) | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (0.0–9.0) | 4.5 (3.0–8.0) | 0.08c | – |

| Mean ESSPRI score during follow-up | 5.7 (0–9.7) | 7.2 (2.3–9.1) | 5.9 (5.7–5.9) | 0.05 | – |

| Clinical systemic involvement (ever) | 253/357 (70.9%) | 26/34 (76.5%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.77 | – |

| Domain of the ESSDAI (ever during follow-up) | |||||

| Constitutional | 28 (7.8%) | 6 (17.7%) | 0 | 0.12 | – |

| Lymphadenopathy | 20 (5.6%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| Glandular | 72 (20.2%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.12 | – |

| Articular | 112 (31.4%) | 26 (76.5%) | 2 (50.0%) | <0.0001c | 0.0001 |

| Cutaneous | 37 (10.4%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0 | 0.58 | – |

| Pulmonary | 85 (23.8%) | 8 (23.5%) | 1 (25.0%) | 1.00 | – |

| Renal | 14 (3.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.89 | – |

| PNS | 39 (10.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | 0 | 0.0002c | 0.0108 |

| CNS | 9 (2.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.94 | – |

| Haematological | 127 (16.5%) | 12 (32.4%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.91 | – |

| Biological | 347 (97.2%) | 33 (97.1%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.94 | – |

| Baseline ESSDAI score without muscular domain | 3 (0–25) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–12) | 0.81 | – |

| Mean ESSDAI score without muscular domain during follow-up | 3 (0–24) | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–8) | 0.71 | – |

| Associated fibromyalgia (n=101) | 27/93 | 3/7 | 0/1 | 0.60 | – |

| Lymphoma (ever) | 17/357 (4.8%) | 0/34 | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Baseline biology | |||||

| Anti-SSA antibodies | 207/348 (59.5%) | 18/33 (54.6%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0.93 | – |

| Anti-SSB antibodies | 123/348 (34.5%) | 5/33 (14.7%) | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0.22 | – |

| RF | 82/337 (24.3%) | 5/31 (16.1%) | 0/4 | 0.32 | – |

| Anti-dsDNA antibodies | 36/298 (12.1%) | 2/34 (5.9%) | 0/4 | 0.45 | – |

| CK (U/l) | 75 (22–412) | 149 (31–2208) | 147 (88–291) | <0.0001a,c | – |

| Number of treatments (besides steroids) | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) | 3 (1–4) | 0.0029a,b,c | – |

Data are median (range) unless indicated. a,b,cP < 0.05 comparing confirmed myositis vs no myositis (a), confirmed myositis vs suspected myositis (b) and suspected myositis vs no myositis (c). VAS: visual analogue scale; PNS: peripheral nervous system; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; ESSPRI: EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Related Index; CK: creatinine kinase.

In contrast, patients with confirmed myositis had longer disease duration at inclusion [15.0 (8.0–32.0) years; P = 0.036] and were younger at pSS diagnosis [42 (39–48) years] than the other two groups [without myositis: 5.0 (0.0–30.0) and 53 (17–82) years; with suspected myositis: 5.0 (0.0–26.0) and 51 (24–77) years]. These patients received a greater number of immunomodulatory drugs than the other two groups [3 different drugs (1–4) with confirmed myositis, 1 (0–5) without myositis and 0 (0–3) with suspected myositis; P = 0.0029].

On multivariable analysis (Table 1), clinical variables differentiating the three groups were disease duration (P = 0.011), and articular and peripheral nervous system involvement according to the ESSDAI during follow-up (P = 0.0001 and P = 0.0108, respectively).

The characteristics of the four patients with pSS and myositis are presented in Table 2. Onset of myositis was after onset pSS in all cases, with a median delay of 8 years after pSS (range 2–13 years). When testing available criteria for primary myositis, two of four pSS patients with muscle involvement matched 2017 EULAR/ACR [7] and Lloyd et al. criteria [12] for sIBM. One patient tested positive for anti-cN1A antibodies. In these two patients, myositis was a late manifestation that appeared >10 years after the diagnosis of pSS. Despite a high number of immunomodulatory drugs (four and three), no muscle improvement was observed. This observation further supported the sIBM diagnosis that was considerably delayed in both patients (12.0 and 5.0 years after muscular symptoms onset).

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | M | F | F |

| Age at myositis onset (years) | 49 | 60 | 39 | 49 |

| Delay between pSS and myositis onset (years) | 10 | 13 | 2 | 6 |

| Anti-SSA, -SSB antibodies | SSA, SSB | SSA | None | SSA |

| Antibodies associated with myositis a | anti-cN1A | None | None | None |

| Myalgia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Proximal weakness | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Quadriceps weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Finger flexor weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Dysphagia | Yes | No | No | No |

| Elevated serum creatinine kinase level (U/l) | Yes (205) <1000 | Yes (207) <1000 | Yes (400) <1000 | No |

| Electromyography findings | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic |

| Rimmed vacuoles | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Endomysial infiltrates | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lymphocytes immunostaining | >95% T (CD4+, CD8+), <5% B | 100% T (CD8+, no CD4+), no B | <5% T (CD4+, CD8+), >95% B | Mixed CD4+, CD8+ and CD20+ |

| Invasion of non-necrotic fibres | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| COX-negative fibres | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| sIBM according to Lloyd et al. [12] | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Extra-muscular systemic involvement | Lymphopenia | Bronchiectasis | Glomerulonephritis, arthritis | Arthritis |

| Cancer, delay in terms of pSS onset, myositis onset | None | Lymphoma, 9 y after pSS diagnosis, 4 y before myositis | None | None |

| Immunomodulatory treatments | CS, MTX, IVIG, RTX, CYC | CS, HCQ, IVIG, RTX | CS, MTX | CS, HCQ, MTX |

| Muscle response | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | M | F | F |

| Age at myositis onset (years) | 49 | 60 | 39 | 49 |

| Delay between pSS and myositis onset (years) | 10 | 13 | 2 | 6 |

| Anti-SSA, -SSB antibodies | SSA, SSB | SSA | None | SSA |

| Antibodies associated with myositis a | anti-cN1A | None | None | None |

| Myalgia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Proximal weakness | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Quadriceps weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Finger flexor weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Dysphagia | Yes | No | No | No |

| Elevated serum creatinine kinase level (U/l) | Yes (205) <1000 | Yes (207) <1000 | Yes (400) <1000 | No |

| Electromyography findings | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic |

| Rimmed vacuoles | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Endomysial infiltrates | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lymphocytes immunostaining | >95% T (CD4+, CD8+), <5% B | 100% T (CD8+, no CD4+), no B | <5% T (CD4+, CD8+), >95% B | Mixed CD4+, CD8+ and CD20+ |

| Invasion of non-necrotic fibres | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| COX-negative fibres | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| sIBM according to Lloyd et al. [12] | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Extra-muscular systemic involvement | Lymphopenia | Bronchiectasis | Glomerulonephritis, arthritis | Arthritis |

| Cancer, delay in terms of pSS onset, myositis onset | None | Lymphoma, 9 y after pSS diagnosis, 4 y before myositis | None | None |

| Immunomodulatory treatments | CS, MTX, IVIG, RTX, CYC | CS, HCQ, IVIG, RTX | CS, MTX | CS, HCQ, MTX |

| Muscle response | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Autoantibodies associated with myositis tested were anti-cN1A, -AMA2, -Mi-2, -MDA5, -TIF-1γ, -SAE, -NXP2, -HMGCR, -SRP, -PM/Scl, -Ku, -U1-RNP, -Jo1, -PL7, -PL12, -EJ, -OJ, -Ha, -KS, -Zo. COX: cytochrome oxydase; pSS: primary SS; RTX: rituximab; sIBM: sporadic inclusion body myositis; y: years.

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | M | F | F |

| Age at myositis onset (years) | 49 | 60 | 39 | 49 |

| Delay between pSS and myositis onset (years) | 10 | 13 | 2 | 6 |

| Anti-SSA, -SSB antibodies | SSA, SSB | SSA | None | SSA |

| Antibodies associated with myositis a | anti-cN1A | None | None | None |

| Myalgia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Proximal weakness | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Quadriceps weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Finger flexor weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Dysphagia | Yes | No | No | No |

| Elevated serum creatinine kinase level (U/l) | Yes (205) <1000 | Yes (207) <1000 | Yes (400) <1000 | No |

| Electromyography findings | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic |

| Rimmed vacuoles | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Endomysial infiltrates | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lymphocytes immunostaining | >95% T (CD4+, CD8+), <5% B | 100% T (CD8+, no CD4+), no B | <5% T (CD4+, CD8+), >95% B | Mixed CD4+, CD8+ and CD20+ |

| Invasion of non-necrotic fibres | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| COX-negative fibres | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| sIBM according to Lloyd et al. [12] | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Extra-muscular systemic involvement | Lymphopenia | Bronchiectasis | Glomerulonephritis, arthritis | Arthritis |

| Cancer, delay in terms of pSS onset, myositis onset | None | Lymphoma, 9 y after pSS diagnosis, 4 y before myositis | None | None |

| Immunomodulatory treatments | CS, MTX, IVIG, RTX, CYC | CS, HCQ, IVIG, RTX | CS, MTX | CS, HCQ, MTX |

| Muscle response | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | M | F | F |

| Age at myositis onset (years) | 49 | 60 | 39 | 49 |

| Delay between pSS and myositis onset (years) | 10 | 13 | 2 | 6 |

| Anti-SSA, -SSB antibodies | SSA, SSB | SSA | None | SSA |

| Antibodies associated with myositis a | anti-cN1A | None | None | None |

| Myalgia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Proximal weakness | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Quadriceps weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Finger flexor weakness | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Dysphagia | Yes | No | No | No |

| Elevated serum creatinine kinase level (U/l) | Yes (205) <1000 | Yes (207) <1000 | Yes (400) <1000 | No |

| Electromyography findings | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic | Myogenic |

| Rimmed vacuoles | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Endomysial infiltrates | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lymphocytes immunostaining | >95% T (CD4+, CD8+), <5% B | 100% T (CD8+, no CD4+), no B | <5% T (CD4+, CD8+), >95% B | Mixed CD4+, CD8+ and CD20+ |

| Invasion of non-necrotic fibres | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| COX-negative fibres | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| sIBM according to Lloyd et al. [12] | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Extra-muscular systemic involvement | Lymphopenia | Bronchiectasis | Glomerulonephritis, arthritis | Arthritis |

| Cancer, delay in terms of pSS onset, myositis onset | None | Lymphoma, 9 y after pSS diagnosis, 4 y before myositis | None | None |

| Immunomodulatory treatments | CS, MTX, IVIG, RTX, CYC | CS, HCQ, IVIG, RTX | CS, MTX | CS, HCQ, MTX |

| Muscle response | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Autoantibodies associated with myositis tested were anti-cN1A, -AMA2, -Mi-2, -MDA5, -TIF-1γ, -SAE, -NXP2, -HMGCR, -SRP, -PM/Scl, -Ku, -U1-RNP, -Jo1, -PL7, -PL12, -EJ, -OJ, -Ha, -KS, -Zo. COX: cytochrome oxydase; pSS: primary SS; RTX: rituximab; sIBM: sporadic inclusion body myositis; y: years.

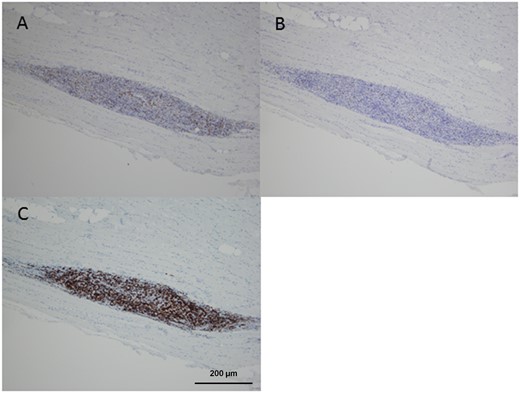

The two other pSS patients with muscle involvement matched 2017 EULAR/ACR criteria for polymyositis without fulfilling the criteria for a well-recognized subset of myositis (e.g. sIBM, dematomyositis, antisynthetase syndrome and necrotizing autoimmune myositis). Indeed, they did not show cutaneous signs of primary myositis, no myositis-specific auto-antibody was detected in baseline serum, and muscle pathology revealed invasion of non-necrotic fibres without clinical or histological features of sIBM. Interestingly, as opposed to the patients with pSS patients matching sIBM criteria, a significant proportion of B lymphocytes were found in the muscle biopsies, and even represented the most predominant component of the inflammatory infiltrate in one patient (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Most importantly, in contrast to the pSS patients matching sIBM criteria, steroids plus MTX were efficient in achieving remission of muscle disease (normal muscle strength and serum creatinine kinase level), which was maintained after prolonged follow-up.

Immunohistochemical staining of muscle biopsy from patient 3 (A) anti-CD4, (B) anti-CD8 and (C) anti-CD20 antibodies. Magnification ×100.

Discussion

These results significantly refine current knowledge on myositis in pSS. Using a large prospective multicentre database of pSS patients, we demonstrated that although suspected in about 10% of pSS cases, myositis is present in only 1% of the whole pSS ASSESS cohort.

We further identified that duration of pSS, which was 3-fold longer at enrolment in patients with confirmed myositis, was the sole factor associated with myositis. By contrast, suspected but not confirmed myositis was independently associated with painful involvement, as illustrated by 20% higher scores of patient-reported signs, articular involvement (present in more than three-quarters of patients) and/or peripheral nervous system involvement (present in more than one-third). Of note, ESSPRI score was higher for patients with suspected but not confirmed myositis than others, which suggests that they had a higher level of symptoms that may have falsely oriented the clinician to the possibility of myositis.

Taking advantage of a long follow-up and an in-depth clinical, histological and serological characterization of muscle involvement, we showed that myositis in our pSS cohort involves two inflammatory muscle conditions with different responses to treatment.

First, 0.5% of pSS patients matched criteria for sIBM, a prevalence that is very close to the 0.6% estimation reported by Kanellopoulos et al. [3] in a retrospective analysis of their monocentric cohort. Thus, sIBM prevalence in pSS is 500-fold higher than in the general population [2.01/100 000 (95% CI: 1.51, 2.69)] [13]. Moreover, on multivariate analysis, disease duration differentiated pSS patients with and without myositis >20 years in pSS patients with criteria for sIBM. Finally, sIBM and pSS may share pathophysiological mechanisms because lymphocytic infiltration, deregulation of autophagy and anti-cN1A auto-immunity in a human leucocyte antigen-DR3 genetic background are present in both diseases [14, 15]. Hence, these data support that sIBM is of immunological origin and may be a late complication of pSS.

As a second inflammatory muscle condition, 0.5% of pSS patients had muscle involvement that was not classifiable as a well-defined primary myositis other than polymyositis. Indeed, these patients did not show extra-muscular manifestations or auto-antibodies associated with a definite myositis subtype. Histological examination revealed endomysial infiltrates with a significant proportion of B lymphocytes (even representing the most predominant infiltrating cells in one of the two patients) focally invading muscle fibres that did not feature sIBM characteristics. Altogether, these characteristics suggest that these patients exhibited a ‘pure’ pSS-related myositis. In these patients, myositis represents a systemic complication of pSS. In contrast to patients matching sIBM criteria, these patients completely responded to simple immunomodulatory treatment.

In conclusion, myositis, frequently suspected in patients with painful manifestations of pSS, actually occurs in only 1% of patients. Especially in patients with long-lasting pSS and no response to treatment, sIBM, which may be a complication of pSS, should be carefully considered.

Funding: The Assessment of Systemic Signs and Evolution in Sjögren’s Syndrome (ASSESS) cohort was supported by grants from the French Ministry of Health (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique) awarded in 2005 to the ASSESS national cohort and the French Society of Rheumatology.

Disclosure statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Comments