-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Florian Cohen, Eric Ernest Gabison, Sophie Stéphan, Rakiba Belkhir, Gaetane Nocturne, Anne-Laurence Best, Oscar Haigh, Emmanuel Barreau, Marc Labetoulle, Raphaele Seror, Antoine Rousseau, Peripheral ulcerative keratitis in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking tocilizumab: paradoxical manifestation or insufficient efficacy?, Rheumatology, Volume 60, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages 5413–5418, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab093

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a severe corneal condition associated with uncontrolled RA. Tocilizumab (TCZ) is used to control RA, however, episodes of paradoxical ocular inflammation have been reported in TCZ-treated patients. We report a case series of PUK in TCZ-treated RA patients with ophthalmological and systemic findings and discuss the potential underlying mechanisms.

Four patients (six eyes), 47–62 years of age, were included. At the onset of PUK, the median duration of RA was 13 years [interquartile range (IQR) 3–13] and the median treatment with TCZ was 9 months (IQR 3–14). Two patients had active disease [28-joint DAS (DAS28) >3.2] and the disease was controlled in two patients (DAS28 ≤3.2).

TCZ was initially replaced by another immunomodulatory treatment in all patients and later reintroduced in two patients without PUK recurrence. Corneal inflammation was controlled in all cases with local and systemic treatments, with severe visual loss in one eye.

PUK may occur in patients with long-standing RA after a switch to TCZ and can be interpreted, depending on the context, as insufficient efficacy or a paradoxical manifestation. These cases highlight the urgent need for reliable biomarkers of the efficacy and paradoxical reactions of biologics.

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a vision-threatening condition associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

In tocilizumab-treated RA patients, PUK may be due to insufficient efficacy or a paradoxical effect.

Switching immunomodulatory therapy is necessary in cases of PUK in tocilizumab-treated RA patients.

Introduction

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a rare and blinding inflammatory condition associated with systemic diseases, including RA [1]. In this context, PUK is usually considered a marker of active systemic disease [2]. Tocilizumab (TCZ), a monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-6, plays a pivotal role in the regulation of immune cell proliferation and differentiation [3]. It is efficient in both early, severe and active forms of RA [4] and in inflammatory ocular diseases such as non-infectious uveitis and scleritis [5, 6]. As with other biologics, treatment with TCZ may be associated with paradoxical manifestations that are poorly understood [7, 8]. These manifestations occur during biological agent therapy and are defined as pathological conditions that are usually not associated with the underlying disease or that usually respond to this class of drug [8]. Paradoxical manifestations have been reported in 0.6% of TCZ-treated patients [7]. TCZ-associated paradoxical ophthalmic manifestations have rarely been reported and include anterior uveitis, scleritis and one case of PUK [7, 9, 10]. In this study we report a case series of PUK in TCZ-treated RA patients that also summarizes a key question that clinicians consider in this situation: is PUK caused by a paradoxical manifestation or by insufficient control of the disease?

Methods

This retrospective case series includes consecutive cases of PUK in TCZ-treated RA patients who were managed at two tertiary centres in Paris (Bicêtre and Bichat Hospitals) between April 2014 and May 2018. Diagnosis of PUK was made clinically in the presence of a crescent-shaped ulceration of the peripheral cornea with associated epithelial defect, underlying stromal infiltrate and adjacent vascular congestion. This study was approved by the Société Française d’Ophtalmologie (IRB#00008855), adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and all patients gave their written consent. Ophthalmological data were collected on the extension of corneal ulcers, initial and final best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), ophthalmic treatments and complications. Rheumatologic data included RA duration and activity assessed with the 28-joint DAS (DAS28), previous use of DMARDs or biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) and the duration and dosage of TCZ treatment. CRP levels were recorded at the time of PUK onset.

Results

Four patients (three males, one female), ages 47–62 years (median 56.5 years) were included. All patients had a history of dry eye disease (DED), including one with associated SS. None had a history of PUK or scleritis. At PUK onset, the median duration of RA was 13 years [interquartile range (IQR) 3–13] and patients had been treated with TCZ for a median of 9 months (IQR 3–14). The median DAS28 was 4.0 (IQR 1.6–6.7) and CRP was negative in all patients. PUK was bilateral in two cases, with concurrent involvement of both eyes in one patient and sequential involvement in the other patient. One eye of a patient with unilateral involvement presented with corneal perforation. Surgical intervention with amniotic membrane graft transplantation (AMT) was performed in three eyes of two patients. The median follow-up was 41 months (IQR 33–50). Visual outcome was good in four eyes (three patients). One patient experienced severe and irreversible visual loss in one eye. TCZ was initially discontinued in all patients, with a negative rechallenge in two patients. None had recurrence of either PUK or scleritis during follow-up.

Case descriptions

Patient 1

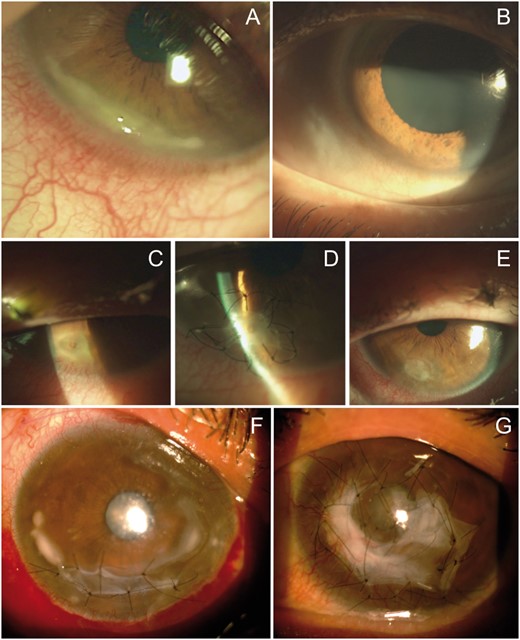

Patient 1 is a male in his 40s, current everyday smoker, with erosive RA evolving for 13 years and long-standing DED had been switched to TCZ 13 months before presentation because of limited efficacy of previous treatments (Table 1). He presented with PUK of the right eye (Fig. 1A). On presentation, the DAS28 was 3.2 (low activity). Local treatments included hourly topical dexamethasone, antibiotics and lubricant eye drops (Supplementary Table 2, available at Rheumatology online). TCZ was switched to rituximab. Ophthalmological evolution was favourable, with complete corneal healing in 1 month (Fig. 1B). However, rituximab did not control articular manifestations and TCZ was reintroduced 13 months later without recurrence of PUK (37 months after reintroduction).

Patient 1. (A) Slit lamp photograph of inferotemporal PUK of the right eye with a crescent-shaped ulcer, stromal infiltration and adjacent vascular congestion. (B) Slit lamp photograph at last follow-up visit: complete healing of the cornea. (C–E) Patient 2. (C) PUK complicated with corneal perforation. (D) Initial repair using sutured multilayer AMT. (E) At the 1 month postoperative visit: suture removal and corneal integration of AMT. (F, G) Patient 4. (F) Right eye, with extensive PUK with sutured inlay AMT to prevent corneal perforation. (G) Left eye, with extensive crescent-shaped ulcers covered with AMT.

| Patient . | RA disease duration, years . | Erosive . | Rheumatoid nodules . | Pulmonary involvement . | Smoking status . | Anti-CCP . | Other autoimmune disease . | Previous DMARDs or bDMARDs before TCZ . | TCZ dosage, mg/ frequency/ route . | TCZ treatment duration, months . | DAS28 . | CRP, mg/dl . | ESR, mm/h . | Follow-up, months . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | + | − | − | CES | + | − | Adalimumab Etanercept Rituximab Abatacept Leflunomide | 680/4 weeks/i.v. | 14 | 3.2 | 6 | 12 | 50 |

| 2 | 13 | + | − | − | FS | + | − | Methotrexate Infliximab Abatacept Adalimumab | 162/week/s.c. | 7 | 1.6 | <5 | 2 | 34 |

| 3 | 10 | + | − | − | NS | − | − | Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab | 640/4 weeks/i.v. | 3 | 6.7 | <5 | 32 | 33 |

| 4 | 31 | + | + | + | NS | + | SS | Allochrystine Salazopyrine Ciclosporin Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab Golimumab Leflunomide Rituximab Abatacept | 500/4 weeks/i.v. | 11 | 4.8 | <5 | 37 | 48 |

| Patient . | RA disease duration, years . | Erosive . | Rheumatoid nodules . | Pulmonary involvement . | Smoking status . | Anti-CCP . | Other autoimmune disease . | Previous DMARDs or bDMARDs before TCZ . | TCZ dosage, mg/ frequency/ route . | TCZ treatment duration, months . | DAS28 . | CRP, mg/dl . | ESR, mm/h . | Follow-up, months . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | + | − | − | CES | + | − | Adalimumab Etanercept Rituximab Abatacept Leflunomide | 680/4 weeks/i.v. | 14 | 3.2 | 6 | 12 | 50 |

| 2 | 13 | + | − | − | FS | + | − | Methotrexate Infliximab Abatacept Adalimumab | 162/week/s.c. | 7 | 1.6 | <5 | 2 | 34 |

| 3 | 10 | + | − | − | NS | − | − | Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab | 640/4 weeks/i.v. | 3 | 6.7 | <5 | 32 | 33 |

| 4 | 31 | + | + | + | NS | + | SS | Allochrystine Salazopyrine Ciclosporin Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab Golimumab Leflunomide Rituximab Abatacept | 500/4 weeks/i.v. | 11 | 4.8 | <5 | 37 | 48 |

CES: current everyday smoker; FS: former smoker; NS: never smoker.

| Patient . | RA disease duration, years . | Erosive . | Rheumatoid nodules . | Pulmonary involvement . | Smoking status . | Anti-CCP . | Other autoimmune disease . | Previous DMARDs or bDMARDs before TCZ . | TCZ dosage, mg/ frequency/ route . | TCZ treatment duration, months . | DAS28 . | CRP, mg/dl . | ESR, mm/h . | Follow-up, months . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | + | − | − | CES | + | − | Adalimumab Etanercept Rituximab Abatacept Leflunomide | 680/4 weeks/i.v. | 14 | 3.2 | 6 | 12 | 50 |

| 2 | 13 | + | − | − | FS | + | − | Methotrexate Infliximab Abatacept Adalimumab | 162/week/s.c. | 7 | 1.6 | <5 | 2 | 34 |

| 3 | 10 | + | − | − | NS | − | − | Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab | 640/4 weeks/i.v. | 3 | 6.7 | <5 | 32 | 33 |

| 4 | 31 | + | + | + | NS | + | SS | Allochrystine Salazopyrine Ciclosporin Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab Golimumab Leflunomide Rituximab Abatacept | 500/4 weeks/i.v. | 11 | 4.8 | <5 | 37 | 48 |

| Patient . | RA disease duration, years . | Erosive . | Rheumatoid nodules . | Pulmonary involvement . | Smoking status . | Anti-CCP . | Other autoimmune disease . | Previous DMARDs or bDMARDs before TCZ . | TCZ dosage, mg/ frequency/ route . | TCZ treatment duration, months . | DAS28 . | CRP, mg/dl . | ESR, mm/h . | Follow-up, months . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | + | − | − | CES | + | − | Adalimumab Etanercept Rituximab Abatacept Leflunomide | 680/4 weeks/i.v. | 14 | 3.2 | 6 | 12 | 50 |

| 2 | 13 | + | − | − | FS | + | − | Methotrexate Infliximab Abatacept Adalimumab | 162/week/s.c. | 7 | 1.6 | <5 | 2 | 34 |

| 3 | 10 | + | − | − | NS | − | − | Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab | 640/4 weeks/i.v. | 3 | 6.7 | <5 | 32 | 33 |

| 4 | 31 | + | + | + | NS | + | SS | Allochrystine Salazopyrine Ciclosporin Methotrexate Etanercept Adalimumab Golimumab Leflunomide Rituximab Abatacept | 500/4 weeks/i.v. | 11 | 4.8 | <5 | 37 | 48 |

CES: current everyday smoker; FS: former smoker; NS: never smoker.

Patient 2

Patient 2 is a male in his 60s, former smoker, with erosive RA diagnosed 13 years earlier who was switched to TCZ after failure of multiple treatment modalities including DMARDs and bDMARDs (Table 1). The patient was treated for severe DED (with lubricant eyedrops, punctal plugs and topical ciclosporin) but did not have SS. He was referred to the department of ophthalmology for a perforated PUK of the right eye (Fig. 1C) 7 months after starting TCZ. On presentation, the articular manifestations were in remission. The patient underwent surgical repair of the corneal perforation using multilayer AMT (Fig. 1D) and was prescribed systemic antibiotics (to prevent ocular superinfection). This treatment resulted in recovery of corneal integrity (Fig. 1E). The patient simultaneously received three i.v. pulses of methylprednisolone (MP) immediately following AMT. The postoperative regimen included dexamethasone, antibiotic and lubricating eyedrops. As a paradoxical reaction was suspected, TCZ was replaced with tapering doses of oral prednisone (1 mg/kg) over a 3 month period accompanied by rituximab infusions.

Patient 3

Patient 3 is a male in his 50s with long-standing erosive RA who was switched to TCZ 3 months before referral to the department of ophthalmology for PUK. He had a history of DED treated with lubricant and ciclosporin eyedrops and was negative for SS (negative anti-SSA and anti-SSB and no focal sialadenitis on minor salivary gland biopsy). PUK was bilateral and inferior with mild corneal thinning and the patient had very active RA (DAS28 = 6.7 without biological inflammatory syndrome). Therapeutic management of PUK included repeated orbital floor injections of dexamethasone and dexamethasone eyedrops. Ciclosporin and autologous serum eyedrops were added to manage DED. TCZ was replaced with rituximab, providing a fast resolution of the corneal inflammation.

Patient 4

Patient 4 was a female in her 50s who had erosive RA evolving for 31 years associated with secondary SS (ocular dryness and anti-SSA), pulmonary involvement and rheumatoid nodules. The patient was previously treated with various medical treatments (Table 1) and was finally switched to i.v. TCZ. After 11 months of i.v. TCZ treatment, extensive PUK developed in the left eye with major corneal infiltration and thinning (Fig. 1G). Clinically, RA was active, with a DAS28 of 4.8. She was treated with three i.v. pulses of MP, repeated dexamethasone orbital floor injections and two separate multilayer AMT procedures. One month after the first episode the patient presented with severe PUK in the opposite eye (Fig. 1F), which led to halting TCZ, three new MP pulses, i.v. cyclophosphamide and oral azathioprine. A multilayer AMT was performed to prevent corneal perforation. TCZ was reintroduced after cyclophosphamide pulses for 20 months, with no recurrence of PUK (for 28 months). The final BCVA was 20/50 in the right eye and counting fingers in the left eye.

Discussion

The observation from this case series indicates that in patients 1 and 2, PUK occurred in patients on TCZ when the RA activity was low or absent. However, in patient 2, rechallenge was negative. However, RA was moderately to highly active in patients 3 and 4, indicating that TCZ was not adequately controlling the disease.

IL-6 plays an important role in the pathophysiology of both RA and ocular inflammatory diseases [11, 12]. Additionally, IL-6 is required for wound healing and repair functions and for corneal epithelial tissue regeneration [13, 14]. Experimental studies have linked paradoxical reactions to TCZ with local overproduction of IL-6 in tissues experiencing pathology in response to systemic depletion of IL-6 by TCZ treatment [15]. Alternately, although rare, the development of anti-TCZ antibodies may reduce its efficacy and cause manifestations that may appear as paradoxical; however, this has never been demonstrated [16]. Finally, the depletion of IL-6 at the level of the cornea may play a deleterious role through dysregulation of corneal epithelial healing [13, 14]. In our series, all patients had pre-existing DED, which involves local inflammation and corneal epithelial defects (superficial punctate keratitis) that may also contribute to the pathogenesis of PUK [17].

Switching immunomodulatory therapy seems necessary in cases of PUK in TCZ-treated RA patients as long as TCZ is not efficacious or is hypothetically involved in a severe paradoxical effect. In this context, rituximab seems a reasonable option. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of rituximab in RA-associated vasculitic manifestations such as PUK [18] and case series have reported good efficacy of rituximab in RA-associated PUK [19, 20]. Surgical procedures are required in case of impending or definite corneal perforations and local treatments are never sufficient [21].

We observed the reverse demographic to what would be expected in RA, with three males and only one female, but it is well known that male gender is a risk factor for vasculitic manifestations of RA such as PUK [22]. Gender could also be questioned when considering the response to TCZ. Indeed, experimental studies have shown that women have greater in vivo pro-inflammatory responses than men, with significantly higher increases in plasma TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations [23]. However, there is currently no available evidence for an influence of gender on response to TCZ in RA patients [24].

Although our study is limited by the number of cases, PUK is extremely rare and this is the first series to characterize PUK in patients on TCZ therapy. Additionally, there was no evidence of the highly unlikely occurrence of anti-TCZ antibodies.

To summarize, rare cases of PUK occur in patients with long-standing RA after a switch to TCZ. This event should be interpreted, depending on the systemic context, as an insufficient efficacy or a paradoxical manifestation. However, the complexity of certain clinical situations highlights the urgent need for reliable biomarkers of the efficacy and paradoxical effects of biologics and for further studies on larger cohorts.

Acknowledgements

All authors participated in the acquisition of data, designing the analyses, interpreting the results and writing the manuscript.

Funding: None declared.

Disclosure statement: E.E.G. has been an occasional consultant for Sanofi, Zeiss, Dompe, Horus, Santen and Thea outside the scope of this work. M.L. has been an occasional consultant for Alcon, Allergan, Bausch and Lomb, Dompe, Horus, MSD, Novartis, Santen, Shire and Thea outside the scope of this work. R.S. has been an occasional consultant for Roche-Chugai, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis, Fresenius Kabi, Amgen and Eli Lilly outside the scope of this work. A.R. has been an occasional consultant for Novartis, Allergan, Pfizer, Shire and Thea outside the scope of this work. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this study are all available in this article.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

Comments