-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elea Giménez-Toledo, Julia Olmos-Peñuela, Elena Castro-Martínez, François Perruchas, The forms of societal interaction in the social sciences, humanities and arts: Below the tip of the iceberg, Research Evaluation, Volume 33, 2024, rvad016, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvad016

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Science policymakers are devoting increasing attention to enhancing the social valorization of scientific knowledge. Since 2010, several international evaluation initiatives have been implemented to assess knowledge transfer and exchange practices and the societal impacts of research. Analysis of these initiatives would allow investigation of the different knowledge transfer and exchange channels and their effects on society and how their effects could be evaluated and boosted. The present study analyses the transfer sexenio programme, which is a first (pilot) assessment that was conducted in Spain to evaluate the engagement of individual researchers in knowledge transfer to and knowledge exchange with non-academic stakeholders, including professionals and society at large. The breadth of the information and supporting documentation available (more than 16,000 applications and 81,000 contributions) allows an exploration of knowledge valorization practices in terms of the transfer forms used and the researchers involved—distinguishing between the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) and Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts (SSHA) areas. By focusing on SSHA fields, we explore knowledge dissemination via enlightenment or professional outputs. We conduct quantitative and qualitative analysis which provide a more comprehensive overview of knowledge transfer practices in Spain in the SSHA field, in particular, and has implications for future assessment exercises.

In Memoriam

Paul Benneworth did not directly contribute to writing this document; however, its core ideas emerged from a ‘brainstorming’ session in which Paul was his usual energetic and imaginative self. We have shared Paul's interest in the valorisation of SSHA research for more than 10 years. In September 2019, we started planning our collaborations around the study of diffusion mechanisms for SSHA during the RESSH 2019 conference in Valencia. We were motivated by the relevance of those types of activities that, while very common in the field of SSHA, were relatively poorly studied in comparison with other commercial and formal knowledge transfer activities. Our first thoughts on this topic were presented at the December 2019 KTI Conference, Assessing Knowledge Transfer and Impact (Benneworth et al. 2019). Following this line of research, in February 2020 we agreed with Paul to conduct a more in-depth study on the outreach practices of SSHA scholars, should the ANECA agency in Spain be willing to make their data on this available to us. This article results from this agreement and study, and we are delighted to have contributed to Paul's research interests by providing more evidence on transfer practices, shedding further light on the societal role played by SSHA. Rest in peace, Paul; we miss your brilliant mind.

1. Introduction

The societal impact of science has received increased attention over the last decades (Bornmann 2013; Penfield et al. 2014; Samuel and Derrick 2015; European Commission 2020; Smit and Hessels 2021). The emphasis on science and society and the need for research to be relevant to both citizens and professionals have narrowed the focus of science policy discourse (Benneworth and Jongbloed 2010; Muhonen, Benneworth and Olmos-Peñuela 2019; Benneworth et al. 2022). This emphasis is being reflected in project proposals and researcher evaluation processes.

Assessments of research valorization and societal impact conducted in different countries over the last few years1 reveal a link between the scholarly and non-academic communities. Analyses of these assessment initiatives, based on real cases, are providing valuable information on the range of knowledge valorization practices and the effects generated.

Academics have highlighted the complexities involved in assessing societal impact, arising from the difficulties involved in attributing a research contribution to a specific effect or identifying the time lag between the research activity and the societal effect produced and its beneficiaries (Samuel and Derrick 2015; Reale et al. 2018). For these reasons, rather than focusing on the knowledge recipient side (and, hence, on the societal impact of research), in this article we investigate science valorization practices and knowledge transfer and exchange processes, focusing on the researcher side. Examination of this body of work conducted from the researcher side allows us to identify areas that have been relatively understudied and to define our contributions to the field.

Traditionally, research on knowledge valorization has been biased towards the study of commercial and/or productive channels2 and STEM fields (Perkmann et al. 2021), although in the last few years the fields studied have been extended (e.g. Reale et al. 2018; Bonaccorsi, Chiarello and Fantoni 2021a). We add to this stream of work by providing a more comprehensive landscape of researcher engagement in knowledge valorization by covering all fields. This is in line with our first research objective (addressed in Study 1 of this article), which is to provide a better understanding of the knowledge transfer forms used across fields, distinguishing between SSHA and STEM, to connect science and society.

However, the main focus of the article is to explore SSHA knowledge dissemination patterns (addressed in Study 2 of this article). By doing so, we focus on all academic production, aimed not necessarily at communication and validation among experts (described, generally, as ‘scientific output’), but also as a way to disseminate knowledge to non-scholars. Following the terminology proposed by Sivertsen (2022), we distinguish between two types of dissemination outputs: those aimed at communication of value or public utility (enlightenment outputs) and those aimed at professionals (professional outputs). Our interest is in the relatively understudied dissemination channels, that is, enlightenment and professionally oriented outputs, which lie below the tip of the iceberg and include written or audio-visual material (Bozeman 2000; Sivertsen 2022) that facilitates potential users’ access to scientific knowledge. We consider the tip of the iceberg to consist of R&D contracts and commercial knowledge transfer channels, which have received more research attention because they are easier to measure and trace (Olmos-Peñuela, Benneworth and Castro-Martínez 2015a).

Based on this distinction, we aim at providing a better understanding of the patterns of SSHA researchers’ dissemination through enlightenment and professional outputs. We focus on these two output types for several reasons: (1) the scant attention in the knowledge transfer literature paid to dissemination via these channels and materials; (2) the seeming greater importance in the SSHA compared to the STEM fields of knowledge exchange practices via dissemination and; (3) the need for a better understanding of the types of dissemination materials produced by SSHA disciplines, for enlightenment and professional purposes, to allow a more comprehensive picture of the dissemination dynamics in this area and the creation of value for society (Olmos-Peñuela, Castro-Martínez and Fernández-Esquinas 2014b; Perkmann et al. 2021). Therefore, our second objective is to explore the extent to which SSHA researchers produce enlightenment and professional outputs and to propose a typology of those outputs which could be used for future research in other fields and contexts.

To address our research objectives, we conduct two empirical studies, both based on original data derived from the contributions submitted to the Spanish transfer sexenio experience. The transfer sexenio is a pilot evaluation process conducted in 2018 to assess the efforts made by researchers to transfer knowledge to and exchange knowledge with non-academic stakeholders. To our knowledge, the dataset resulting from this experience is original and unique for the following reasons: (1) it provides information at the individual (i.e. researcher) level and offers the possibility of analyzing the data at the contribution level, so that it is possible to create a taxonomy of forms of transfer; (2) it contains detailed information of more than 16,000 researchers’ applications and more than 81,000 contributions submitted. Hence, analyzing this dataset provides a unique opportunity to highlight unexplored aspects of the channels, fields, and purposes involved in science–society interaction.

The article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we review the literature on knowledge transfer and exchange processes to highlight the analyzed channels. Section 3 provides the context for the knowledge transfer sexenio evaluation programme based on a brief description of the pilot exercise conducted in 2018. We also describe the two studies carried out to address our research objectives. Sections 4 and 5 present the methods used and the results. Section 6 discusses the implications of our evaluation findings and offers some recommendations for future assessment processes.

2. Review of the knowledge transfer and exchange literature

The body of work on the science–innovation relationship is well-established (Gibbons et al. 1994; Martin 2003; Fernández de Lucio, Vega Jurado and Gutiérrez Gracia 2011). Different dimensions of the knowledge transfer and exchange processes involving the producers of scientific knowledge (i.e. universities, public research organizations) and its potential social users (e.g. firms, public administrations, professional from different sectors, citizens) have been analyzed extensively. They include the characteristics of the actors involved, the types and potential uses of the knowledge exchanged, the channels used, and the contextual conditions influencing the effectiveness of the knowledge transfer and exchange processes (e.g. Bozeman 2000; Polt et al. 2001; Jacobson, Butterill and Goering 2004; Bruneel, D’Este and Salter 2010).

The broad spectrum of transfer channels available to researchers to valorize their knowledge is a source of heterogeneity and depends, to a large extent, on the type of knowledge being exchanged (codified/tacit), the characteristics of the potential users and other individual and institutional conditions (Saviotti 1998).

The knowledge transfer and exchange literature is characterized by the diversity of terms used to refer to the same concept, for example, knowledge transfer mechanisms (Agrawal 2001; Nilsson, Rickne and Bengtsson 2010), knowledge transfer activities, processes or forms (Jacobson, Butterill and Goering 2004; Mitton et al. 2007; Arvanitis and Woerter 2009), transfer media (Bozeman 2000; Bozeman, Rimes and Youtie 2015); mechanisms of collaboration (Bercovitz and Feldman 2011), entrepreneurial activities (Abreu and Grinevich 2013), university–industry interactions (D’Este et al. 2019), and academic engagement3 activities (Perkmann et al. 2013, 2021).

Alongside use of these different terms, previous studies have proposed various frameworks to classify the channels for scientific knowledge transfer and exchange and allow empirical assessment of the extent to which researchers engage in those different channels (Autio and Laamanen 1995; Bekkers and Bodas Freitas 2008; Dutrénit, De Fuentes and Torres 2010; Abreu and Grinevich 2013; Gulbrandsen and Thune 2017; D’Este et al. 2019). For instance, Abreu and Grinevich (2013) propose three categories of transfer channels (formal commercial activities, informal commercial activities, and non-commercial activities), while Gulbrandsen and Thune (2017) suggest four categories (dissemination, research collaboration, commercialization, and training). We do not propose, here, to describe all those frameworks or to enumerate all the knowledge transfer channels identified in the literature (see Fabiano, Marcellusi and Favato 2020 or Perkmann et al. 2021 for recent reviews). Our aim is to identify some areas worthy of further investigation.

Knowledge transfer through enlightenment and professional-oriented outputs is often overlooked in work on knowledge valorization and science–society links (see Perkmann et al. 2021). Thus, while there is a large stream of research on commercial channels of knowledge transfer, comparatively few studies focus specifically on dissemination channels. Among these, Spaapen and Van Drooge (2011) propose the concept of productive interaction and discuss dissemination channels in the context of what they describe as indirect interactions, that is, interactions based on some kind of material ‘carrier’, such as texts or exhibitions. Particular to analyses of dissemination practices is that they are addressed in a ‘joined-up’ way, which includes different kinds of dissemination activities and outputs within a single category, but does not identify the specificities of each activity or material. In addition, these studies tend to focus on ‘traditional’ dissemination channels—e.g. published popular science articles, contributions to the media (Olmos-Peñuela, Castro-Martínez and Fernández-Esquinas 2014b; Gulbrandsen and Thune, 2017), and overlook more innovative enlightenment and professional channels. Therefore, we would suggest, first, that we need more research into the array of dissemination channels that could be used by scientist to valorize their research, for both professional and enlightenment purposes.

At the same time, we need a better understanding of SSHA valorization patterns (Perkmann et al. 2021), since the patterns of collaboration (channels, frequency, and type of non-academic users involved) in the SSHA and STEM fields are different (Bonaccorsi, Chiarello and Fantoni 2021a). SSHA researchers are heavily involved in non-commercial and informal knowledge transfer channels (Olmos-Peñuela, Molas-Gallart and Castro-Martinez 2014c), which are more difficult to capture.4 This has implications for the SSHA field and assessments of its research valorization and transfer practices. The lack of attention to non-commercial transfer channels (e.g. dissemination) and the difficulty involved in their assessment, have likely contributed to the idea that SSHA research is less useful than STEM research (Olmos-Peñuela, Benneworth and Castro-Martinez 2014a). For instance, a recent study of the narratives included in the UK REF suggest that it is more difficult to make credible statements about the value and effects of SSH research (Bonaccorsi et al. 2021b). Thus, we would suggest that more research is needed to explore whether the channels used more frequently by SSHA researchers, are those for which it is more difficult to provide credible narratives to prove the social value of the research conducted. In other words, our second objective is to shed light on whether specific channels are systematically assessed too low and the implications of this for evaluation.

3. Study context

Knowledge transfer was the focus of a recent individual level pilot evaluation exercise in Spain. Although knowledge transfer has been considered in institutional and individual level research evaluations, the pilot transfer sexenio project, conducted in 2018 by the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA), is worthy of special attention for four reasons. First, it was acknowledged as the first successful evaluation of knowledge transfer efforts at the individual level in Spain.5 Second, it takes account of both science policy interest in societal impact and the researchers engaging with society. Third, the transfer sexenio allows a deeper understanding of the range of channels used by researchers in different fields to exchange knowledge and interact with non-scholars. Fourth, it could result in the inclusion of knowledge transfer activities in other evaluation processes. Note, here, that the different dimensions of responsible research evaluation—an axis of EU science policy6—are related to knowledge transfer.

In this section, we provide a brief background to the sexenio initiative, which, initially, was focused on assessing individual research productivity (research sexenio), and then describe the particularities of the transfer sexenio.

3.1 Background: Research sexenio

The Spanish National Commission for the Evaluation of Research Quality (Comisión Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad Investigadora—CNEAI) was created in 1989 as an independent agency of the Education and Science Ministry (Fernández Esquinas et al. 2006), responsible for ex-post assessment of the research conducted by researchers affiliated to universities and public research organizations in Spain (Cañibano Sánchez et al. 2017). The assessment evaluates five contributions—mostly scientific papers—submitted by research sexenio applicants, produced over a 6-year period.

Up to 2009, the types of contributions accepted for the research sexenio included scientific publications (articles, book chapters, books) and technological results (patents and other intellectual property rights). In 2010, to recognize and promote researchers’ engagement in knowledge transfer activities, a new category type ‘field 0’ was added (Jiménez-Contreras, de Moya Anegón and López-Cózar 2003; Artés Pedraja-Chaparro and del Mar Salinas-Jiménez 2017), covering both scientific papers and evidence of knowledge transfer and knowledge exchange (e.g. participation in knowledge-based companies; licenses/patents or other forms of intellectual property protection; R&D contracts with companies; publications derived from collaboration with socio-economic agents to produce commercial products or prototypes; and contributions to industrial or commercial standards regulated by public bodies, professional associations or other entities). To be considered, three out of the five contributions included in field 0 had to be related to knowledge transfer and knowledge exchange.

Thus, from 2010, applicants could choose to submit contributions to the field 0 (common to all fields of knowledge and related to knowledge transfer activities) or to their particular discipline. The number of the contributions submitted under field 0 was small since it was easier for researchers to meet the disciplinary field requirements—scientific publications and patents—and the proportion of rejected applications was much higher in field 0. However, the additional field 0 and requirement of evidence of knowledge transfer materials in the sexenio application was deemed a failure and was discontinued after 2017.

3.2 Knowledge transfer and innovation sexenio

In 2018, ANECA launched a pilot knowledge transfer and innovation sexenio scheme (transfer sexenio), based on assessment of researchers’ engagement in knowledge transfer and innovation activities and replacing the previous field 0. The transfer sexenio was considered separately from the research sexenio and researchers could apply for evaluation to both modalities for the same period. The result of this change was that the transfer sexenio provided a direct incentive for the scientific research community to engage in knowledge transfer and exchange activities. The response received exceeded expectations, with over 16,000 applications from researchers in all disciplines involving more than 81,000 contributions.

The call required a detailed description of the types of contributions related to knowledge transfer activities and covered a wide spectrum of channels and potential social stakeholders. This increased the value of the sexenio in terms of the amount and nature of the information that resulted and offered a unique opportunity to understand the research valorisation processes.

Since it was the first call for the transfer sexenio, it was allowed to include five contributions from a maximum of six (not necessarily consecutive) years produced at any stage in the research career. The only condition was that applicants should have received at least one previous positive research assessment (i.e. award of at least one research sexenio). This condition was intended to ensure that the knowledge transfer activity was based on the applicant's previous scientific activity.

The call established four categories of knowledge transfer and innovation contributions:

Transfer through researcher training (people hired under R&D and innovation projects and contracts; industry and/or business theses supervised; people trained in entrepreneurial culture).

Transfer generating economic value (licensing of intellectual property rights; contracts and projects with companies and institutions; participation in active spin-off companies; patents or other types of registered owned or co-owned knowledge).

Transfer of own knowledge through activities with or within non-academic entities (periods of employment in the public or private sector, commissioning of special services, membership of advisory committees, etc.).

Knowledge transfer generating social value (agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or public administrations for activities of special social value; dissemination via publications (books, book chapters, articles)),7 dissemination of research in the media, professional diffusion (reports for social agents, protocols, clinical guides, codes of practice, creative or cultural products, translations, participation in the drafting of laws and regulations).

Although Spanish science policy uses different measures to promote knowledge transfer and knowledge exchange at both the research project and institutional levels, this call provided a first, clear, individual level incentive for knowledge transfer and was the first call to include such a wide typology and diversity of knowledge transfer and innovation practices, potential stakeholders, and results.

Like the research sexenio, applicants had to submit five items to which the researcher had contributed actively over a 6-year period, and a description of evidence of the impact of these contributions beyond academia. In exceptional cases, a smaller number of especially high-quality contributions with particularly high levels of impact were considered. The call specified also that, to achieve a positive evaluation, the contributions submitted should be distributed between at least two of the four above-mentioned categories.

4. Materials and methods

4.1 Data and analysis (Study 1)

To provide a better understanding of the knowledge transfer channels used across fields to connect science and society, we exploited the database derived by ANECA from the 2018 transfer sexenio call. Based on the 16,316 valid applications assessed by ANECA, we built an ad hoc database that included 81,366 contributions which we classified by type (see Section 3.2). As described above, most applications included five contributions; 0.9% were categorized as ‘exceptional cases’ and included a smaller number of contributions.

Each contribution was assigned to the scientific field to which the applicant was submitting his or her proposal. This resulted into the assignment of applications (and, hence, contributions) into one of the 15 scientific categories used by ANECA for this specific evaluation process: (1) Arts and Humanities; (2) Education; (3) Law; (4) Behavioural and Social Sciences; (5) Economics; (6) Business; (7) Physics and Mathematics; (8) Chemistry; (9) Electronic and Systems Engineering; (10) Informatics Engineering; (11) Mechanical and Navigation Engineering; (12) Chemical and Materials Engineering; (13) Architecture and Civil Engineering; (14) Natural Sciences and Biochemistry; and (15) Health.

To explore differences in success rates by type of contribution, we computed the ratio of number of approved contributions to number of contributions submitted. We then tested to compare success rates among each type of contribution to total success rate. For the P-tests, all the pair-wise differences in proportions were standardized at the 0.05 significance level (See Section 5.1).

| Type of contribution . | Contributions presented (N) . | Contributions approved (N) . | Success rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 7,128 | 3,070 | 43.1− |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 696 | 347 | 49.9 |

| Industry/business theses supervised | 435 | 221 | 50.8 |

| Other | 1,254 | 320 | 25.5− |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 488 | 326 | 66.8+ |

| Patents | 4,325 | 2,150 | 49.7+ |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 29,055 | 16,990 | 58.5+ |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 1,033 | 881 | 85.3+ |

| Other | 922 | 386 | 41.9 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 7,016 | 2,892 | 41.2− |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 9,687 | 5,045 | 52.1+ |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 16,517 | 5,158 | 31.2− |

| Other | 2,810 | 1,150 | 40.9− |

| Total | 81,366 | 38,936 | 47.9 |

| Type of contribution . | Contributions presented (N) . | Contributions approved (N) . | Success rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 7,128 | 3,070 | 43.1− |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 696 | 347 | 49.9 |

| Industry/business theses supervised | 435 | 221 | 50.8 |

| Other | 1,254 | 320 | 25.5− |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 488 | 326 | 66.8+ |

| Patents | 4,325 | 2,150 | 49.7+ |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 29,055 | 16,990 | 58.5+ |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 1,033 | 881 | 85.3+ |

| Other | 922 | 386 | 41.9 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 7,016 | 2,892 | 41.2− |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 9,687 | 5,045 | 52.1+ |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 16,517 | 5,158 | 31.2− |

| Other | 2,810 | 1,150 | 40.9− |

| Total | 81,366 | 38,936 | 47.9 |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Bold indicates significant differences between success rates (%) for a specific type of contribution and the total success rate, at the 0.05 significance level. A success rate for a specific contribution that is higher (lower) than the total, is indicated by ‘+’ (‘–’).

| Type of contribution . | Contributions presented (N) . | Contributions approved (N) . | Success rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 7,128 | 3,070 | 43.1− |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 696 | 347 | 49.9 |

| Industry/business theses supervised | 435 | 221 | 50.8 |

| Other | 1,254 | 320 | 25.5− |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 488 | 326 | 66.8+ |

| Patents | 4,325 | 2,150 | 49.7+ |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 29,055 | 16,990 | 58.5+ |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 1,033 | 881 | 85.3+ |

| Other | 922 | 386 | 41.9 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 7,016 | 2,892 | 41.2− |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 9,687 | 5,045 | 52.1+ |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 16,517 | 5,158 | 31.2− |

| Other | 2,810 | 1,150 | 40.9− |

| Total | 81,366 | 38,936 | 47.9 |

| Type of contribution . | Contributions presented (N) . | Contributions approved (N) . | Success rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 7,128 | 3,070 | 43.1− |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 696 | 347 | 49.9 |

| Industry/business theses supervised | 435 | 221 | 50.8 |

| Other | 1,254 | 320 | 25.5− |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 488 | 326 | 66.8+ |

| Patents | 4,325 | 2,150 | 49.7+ |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 29,055 | 16,990 | 58.5+ |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 1,033 | 881 | 85.3+ |

| Other | 922 | 386 | 41.9 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 7,016 | 2,892 | 41.2− |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 9,687 | 5,045 | 52.1+ |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 16,517 | 5,158 | 31.2− |

| Other | 2,810 | 1,150 | 40.9− |

| Total | 81,366 | 38,936 | 47.9 |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Bold indicates significant differences between success rates (%) for a specific type of contribution and the total success rate, at the 0.05 significance level. A success rate for a specific contribution that is higher (lower) than the total, is indicated by ‘+’ (‘–’).

In order to explore the differences (by type of contribution) between the SSHA and STEM fields, in terms of the proportion of contributions approved, we re-assigned the 15 scientific fields into the two groups of SSHA (fields 1–6) and STEM (fields 7–15). We then constructed SSHA and STEM profiles to capture how the approved contributions were distributed within each field group. Again, we used hypothesis tests to compare differences in proportions between SSHA and STEM (i.e. proportion of approved contributions in SSHA vs. proportion of approved contributions in STEM) and applied them to each type of contribution. Pair-wise differences were standardized at the 0.05 significance level (See Section 5.1).

| . | SSHA . | STEM . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 2.9 | 11.3 | 7.9 |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Industrial/business theses supervised | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Other | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Patents | 0.7 | 8.8 | 5.5 |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 35.3 | 49.4 | 43.6 |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 0.7 | 3.3 | 2.3 |

| Other | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 11.4 | 4.7 | 7.4 |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 20.2 | 8.0 | 13.0 |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 19.9 | 8.7 | 13.2 |

| Other | 5.4 | 1.3 | 3.0 |

| N Total (%) | 15,837 (100) | 23,099 (100) | 38,936 (100) |

| . | SSHA . | STEM . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 2.9 | 11.3 | 7.9 |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Industrial/business theses supervised | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Other | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Patents | 0.7 | 8.8 | 5.5 |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 35.3 | 49.4 | 43.6 |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 0.7 | 3.3 | 2.3 |

| Other | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 11.4 | 4.7 | 7.4 |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 20.2 | 8.0 | 13.0 |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 19.9 | 8.7 | 13.2 |

| Other | 5.4 | 1.3 | 3.0 |

| N Total (%) | 15,837 (100) | 23,099 (100) | 38,936 (100) |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Bold indicates that the proportion of approved contributions is significantly higher in the focal (SSHA or STEM) compared to the other field, at the 0.05% significance level.

| . | SSHA . | STEM . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 2.9 | 11.3 | 7.9 |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Industrial/business theses supervised | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Other | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Patents | 0.7 | 8.8 | 5.5 |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 35.3 | 49.4 | 43.6 |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 0.7 | 3.3 | 2.3 |

| Other | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 11.4 | 4.7 | 7.4 |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 20.2 | 8.0 | 13.0 |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 19.9 | 8.7 | 13.2 |

| Other | 5.4 | 1.3 | 3.0 |

| N Total (%) | 15,837 (100) | 23,099 (100) | 38,936 (100) |

| . | SSHA . | STEM . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer through researcher training | |||

| People hired | 2.9 | 11.3 | 7.9 |

| People trained in entrepreneurial culture | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Industrial/business theses supervised | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Other | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Transfer generating economic value | |||

| License of intellectual property rights | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Patents | 0.7 | 8.8 | 5.5 |

| Contracts and projects with companies and institutions | 35.3 | 49.4 | 43.6 |

| Participation in active spin-off companies | 0.7 | 3.3 | 2.3 |

| Other | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions | 11.4 | 4.7 | 7.4 |

| Transfer generating social value | |||

| Agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or Public Administrations for activities with special social value | 20.2 | 8.0 | 13.0 |

| Publications and dissemination activities | 19.9 | 8.7 | 13.2 |

| Other | 5.4 | 1.3 | 3.0 |

| N Total (%) | 15,837 (100) | 23,099 (100) | 38,936 (100) |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Bold indicates that the proportion of approved contributions is significantly higher in the focal (SSHA or STEM) compared to the other field, at the 0.05% significance level.

4.2 Data and analysis (Study 2)

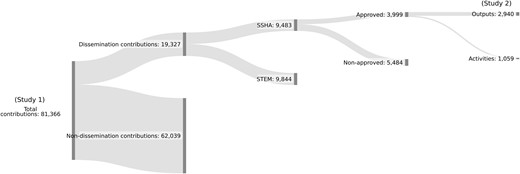

To provide a better understanding of SSHA dissemination, we propose a typology for the different types of dissemination allowing diffusion and transfer of research results to non-academic professionals and stakeholders. We use this typology in the empirical analysis to classify the 2,9408 dissemination output contributions submitted by SSHA researchers assessed positively in the transfer sexenio evaluation programme. A summary of the procedure followed to build the sample for Study 2 is depicted in Figure 1 (and extended in the Supplementary Appendix).

Distribution of contributions related to the samples used in Studies 1 and 2.

Source: Authors based on ANECA data

Categorization of the 2,940 SSHA contributions was based on SSHA discipline, type of material, and purpose of the contribution.

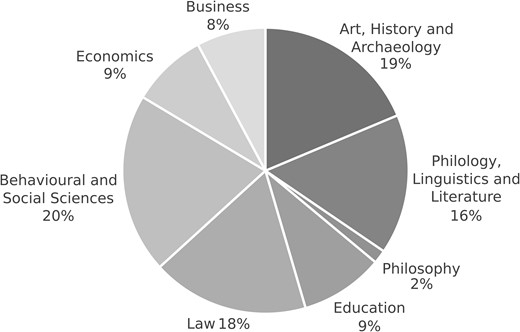

SSHA discipline: We started with SSHA disciplines 1–6 (see Section 4.1.). Because of the high representation of dissemination outputs in the arts and humanities (40%) and to enable more detailed analysis of the SSHA field to take account of its heterogeneity, we reassigned the arts and humanities contributions based on researcher’s departmental affiliation. Thus, arts and humanities are disaggregated into: (1) Arts, History and Archaeology; (2) Philology, Language and Literature; and (3) Philosophy. We also reassigned a few arts and humanities contributions that our qualitative review indicated were a better fit with the disciplines of Behavioural and Social Sciences (119)9, Education (1), Economics (1), and Business (1). Therefore, we classified the 2,940 SSHA contributions into the following disciplines: (1) Arts, History, and Archaeology; (2) Philology, Linguistics, and Literature; (3) Philosophy; (4) Education; (5) Law; (6) Behavioural and Social Sciences; (7) Economics; and (8) Business.

Type of material: We identified seven types of materials used by researchers to generate societal value:

Articles and books: those produced by scholars as result of their research addressed to the general public (society) and/or useful to professionals for decision making: scholarly book series, books (single or multiple authored), book chapters and articles, exhibition catalogues, artistic works or sites, dictionaries, glossaries, atlases, encyclopaedias, introductory essays or notes for artistic productions, didactic units, cartographies, translations, and critical editions aimed specifically at professionals or published in professional media (including musical transcriptions, editions of theatre plays for directors and interpreters). These publication types can be considered both transfer channels and sources of information for non-academic readers. They link the knowledge resulting from academic research to those audiences that require that knowledge to act or to justify their decisions.

Commissioned reports: technical reports and advisory documents for companies, for executive, legislative and judicial authorities/powers, and for other social agents (trades unions, associations, non-governmental organizations, international organizations, etc.).

Guidelines: codes of ethics, codes of professional practice, handbooks, standards, protocols, and regulations.

Libraries and other virtual resources: catalogued virtual libraries of collections or resources (bibliographic, musical, artistic, heritage, law and jurisprudence, social resources, etc.), observatories, barometers, databases, web resource guides, and information websites.

Audio-visual products and software applications: documentaries, films, music recordings, podcasts, animations, computer games, audio-visual presentations with scientific content, video tutorials, and translations and subtitles and computer programs.

Mass media contributions: opinion pieces, analyses, etc. (press, radio, and television).

Scientific contributions in social networks: blogs, YouTube videos, Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter posts and other items.

If the researcher participated directly in the production of audio-visual output, this was categorized as “audio-visual products and applications”; if participation was restricted to providing advice via the media (i.e. not taking part in the audio-visual production), the contribution was categorized as ‘mass media contribution’.

Type of purpose: We distinguished between dissemination outputs, professional, enlightenment, or scholarly purposes. Dissemination outputs with professional purposes provide knowledge that could be exploited by practitioners for decision-making and in their work practices. Dissemination outputs with enlightenment purposes are oriented to the public (society), who may exploit the knowledge embedded in those outputs for personal aims (culture, leisure, understanding of the economy, of society, of politics, of the effect of science and technology, for the development of criteria for decision-making, etc.), in order to better understand the economic and social implications of science and technology, to establish criteria in relation to questions about new scientific findings, to assess the scope and effects of new products and services offered by the market, and to make decisions in areas related to social and political questions (e.g. regarding protection of cultural heritage, active aging, euthanasia, stem cell treatments, vaccines, etc.). The literature refers to hybrid outputs (e.g. publications), which are based on robust scientific work and address academic and other non-scholar audiences (Prins and Spaapen 2017). Although not our main focus in this study, given the hybrid nature of some outputs, scholarly purposes can include outputs aimed initially at dissemination of knowledge beyond the scholarly community. In the context of the transfer sexenio, for this type of dissemination contribution to qualify required the researcher to justify the interest or the usefulness for other social actors (beyond academia).

To identify SSHA dissemination patterns, we constructed profiles by SSHA discipline. We apply hypothesis tests to assess the differences among SSHA disciplines and the whole SSHA field, in terms of the proportion of approved contributions, by type of material. The computed pair-wise differences (SSHA disciplines vs. total SSHA) were standardized at the 0.05 significance level (See Section 5.2). Finally, we used descriptive statistics to explore the type of purpose (enlightenment, professional, or hybrid) of each type of material (See Section 5.2).

Distribution (%) of the dissemination approved outputs, by type of material and SSHA disciplines

| Type of material . | Art, History and Archaeology . | Philology, Linguistics and Literature . | Philosophy . | Education . | Law . | Behavioural and Social Sciences . | Economics . | Business . | % Total SSHA (N) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 68.7 + | 68.2+ | 64.4 | 45.5 | 31.0– | 50.1 | 52.8 | 45.2 | 52.7% (1,549) |

| Commissioned reports | 5.5– | 6.0– | 4.4– | 15.5 | 46.9+ | 18.2 | 29.8+ | 37.4+ | 21.0% (618) |

| Guidelines | 2.6– | 4.7– | 2.2– | 23.5+ | 10.2 | 17.9+ | 3.2– | 11.7 | 10.1% (297) |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 3.3 | 8.4+ | 0.0– | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.4– | 3.4% (101) |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 7.1+ | 2.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 0.8– | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 3.9% (114) |

| Mass media contributions | 12.4+ | 8.8 | 20.0 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 3.0– | 8.0% (234) |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 0.5 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.9% (27) |

| N Total by discipline | 549 | 466 | 45 | 277 | 522 | 599 | 252 | 230 | 2,940 |

| Type of material . | Art, History and Archaeology . | Philology, Linguistics and Literature . | Philosophy . | Education . | Law . | Behavioural and Social Sciences . | Economics . | Business . | % Total SSHA (N) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 68.7 + | 68.2+ | 64.4 | 45.5 | 31.0– | 50.1 | 52.8 | 45.2 | 52.7% (1,549) |

| Commissioned reports | 5.5– | 6.0– | 4.4– | 15.5 | 46.9+ | 18.2 | 29.8+ | 37.4+ | 21.0% (618) |

| Guidelines | 2.6– | 4.7– | 2.2– | 23.5+ | 10.2 | 17.9+ | 3.2– | 11.7 | 10.1% (297) |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 3.3 | 8.4+ | 0.0– | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.4– | 3.4% (101) |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 7.1+ | 2.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 0.8– | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 3.9% (114) |

| Mass media contributions | 12.4+ | 8.8 | 20.0 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 3.0– | 8.0% (234) |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 0.5 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.9% (27) |

| N Total by discipline | 549 | 466 | 45 | 277 | 522 | 599 | 252 | 230 | 2,940 |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Proportions are computed by column. To indicate whether the proportion of approved dissemination contributions is higher (+) or lower (−) for a specific SSHA discipline than the total SSHA, at the 0.05% significance level, we add a superscript showing the direction of the difference (+/−). In the column ‘total’, absolute values are in parentheses.

Distribution (%) of the dissemination approved outputs, by type of material and SSHA disciplines

| Type of material . | Art, History and Archaeology . | Philology, Linguistics and Literature . | Philosophy . | Education . | Law . | Behavioural and Social Sciences . | Economics . | Business . | % Total SSHA (N) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 68.7 + | 68.2+ | 64.4 | 45.5 | 31.0– | 50.1 | 52.8 | 45.2 | 52.7% (1,549) |

| Commissioned reports | 5.5– | 6.0– | 4.4– | 15.5 | 46.9+ | 18.2 | 29.8+ | 37.4+ | 21.0% (618) |

| Guidelines | 2.6– | 4.7– | 2.2– | 23.5+ | 10.2 | 17.9+ | 3.2– | 11.7 | 10.1% (297) |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 3.3 | 8.4+ | 0.0– | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.4– | 3.4% (101) |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 7.1+ | 2.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 0.8– | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 3.9% (114) |

| Mass media contributions | 12.4+ | 8.8 | 20.0 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 3.0– | 8.0% (234) |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 0.5 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.9% (27) |

| N Total by discipline | 549 | 466 | 45 | 277 | 522 | 599 | 252 | 230 | 2,940 |

| Type of material . | Art, History and Archaeology . | Philology, Linguistics and Literature . | Philosophy . | Education . | Law . | Behavioural and Social Sciences . | Economics . | Business . | % Total SSHA (N) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 68.7 + | 68.2+ | 64.4 | 45.5 | 31.0– | 50.1 | 52.8 | 45.2 | 52.7% (1,549) |

| Commissioned reports | 5.5– | 6.0– | 4.4– | 15.5 | 46.9+ | 18.2 | 29.8+ | 37.4+ | 21.0% (618) |

| Guidelines | 2.6– | 4.7– | 2.2– | 23.5+ | 10.2 | 17.9+ | 3.2– | 11.7 | 10.1% (297) |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 3.3 | 8.4+ | 0.0– | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.4– | 3.4% (101) |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 7.1+ | 2.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 0.8– | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 3.9% (114) |

| Mass media contributions | 12.4+ | 8.8 | 20.0 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 3.0– | 8.0% (234) |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 0.5 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.9% (27) |

| N Total by discipline | 549 | 466 | 45 | 277 | 522 | 599 | 252 | 230 | 2,940 |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Proportions are computed by column. To indicate whether the proportion of approved dissemination contributions is higher (+) or lower (−) for a specific SSHA discipline than the total SSHA, at the 0.05% significance level, we add a superscript showing the direction of the difference (+/−). In the column ‘total’, absolute values are in parentheses.

Distribution (%) of dissemination outputs approved, by type of material and by purpose

| Type of material . | Only enlightenment . | Only professional . | Enlightenment and professional . | Professional and scholarly . | Enlightenment and scholarly . | Enlightenment, professional, and scholarly . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 58.3 | 15.8 | 20.5 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Commissioned reports | 0.3 | 90.3 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Guidelines | 1.3 | 64.3 | 33.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 39.6 | 21.8 | 35.6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 69.3 | 6.1 | 22.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Mass media contributions | 70.1 | 2.1 | 27.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 88.9 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| N Total (%) | 1,216 (41.4) | 1,028 (35.0) | 598 (20.3) | 51 (1.7) | 24 (0.8) | 23 (0.8) |

| Type of material . | Only enlightenment . | Only professional . | Enlightenment and professional . | Professional and scholarly . | Enlightenment and scholarly . | Enlightenment, professional, and scholarly . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 58.3 | 15.8 | 20.5 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Commissioned reports | 0.3 | 90.3 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Guidelines | 1.3 | 64.3 | 33.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 39.6 | 21.8 | 35.6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 69.3 | 6.1 | 22.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Mass media contributions | 70.1 | 2.1 | 27.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 88.9 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| N Total (%) | 1,216 (41.4) | 1,028 (35.0) | 598 (20.3) | 51 (1.7) | 24 (0.8) | 23 (0.8) |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Proportions are computed by rows.

Distribution (%) of dissemination outputs approved, by type of material and by purpose

| Type of material . | Only enlightenment . | Only professional . | Enlightenment and professional . | Professional and scholarly . | Enlightenment and scholarly . | Enlightenment, professional, and scholarly . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 58.3 | 15.8 | 20.5 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Commissioned reports | 0.3 | 90.3 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Guidelines | 1.3 | 64.3 | 33.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 39.6 | 21.8 | 35.6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 69.3 | 6.1 | 22.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Mass media contributions | 70.1 | 2.1 | 27.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 88.9 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| N Total (%) | 1,216 (41.4) | 1,028 (35.0) | 598 (20.3) | 51 (1.7) | 24 (0.8) | 23 (0.8) |

| Type of material . | Only enlightenment . | Only professional . | Enlightenment and professional . | Professional and scholarly . | Enlightenment and scholarly . | Enlightenment, professional, and scholarly . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles and books | 58.3 | 15.8 | 20.5 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Commissioned reports | 0.3 | 90.3 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Guidelines | 1.3 | 64.3 | 33.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Libraries and other virtual resources | 39.6 | 21.8 | 35.6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Audio-visual products and applications | 69.3 | 6.1 | 22.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Mass media contributions | 70.1 | 2.1 | 27.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Scientific contributions in social networks | 88.9 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| N Total (%) | 1,216 (41.4) | 1,028 (35.0) | 598 (20.3) | 51 (1.7) | 24 (0.8) | 23 (0.8) |

Source: Authors based on ANECA data.

Note: Proportions are computed by rows.

5. Results

5.1 Knowledge transfer patterns by type of contribution and field (Study 1)

Table 1 presents the distribution of the contributions submitted and approved and the success rates, by type of contribution. The categories that include the highest number of submissions are transfers generating economic value (44.0%) and social value (35.7%).

Regarding the type of contributions submitted, three stand out: contracts with companies, publication and dissemination activities, and contracts or agreements with social value (which together, represent almost 70% of the total submitted). Common to these types of activities is that they are easily justifiable, either because they are included in the corporate databases (contracts and agreements) or because they are materials readily available to researchers (dissemination outputs), which is a requirement of the transfer sexenio call.

If we focus on success rates, on average, almost half of the contributions submitted were approved (47.9%), although there is an important variability by type of contribution. Note, also, that the type ‘other’—included in three of the four categories and representing 6.1% of the contributions submitted—shows a success rate significantly lower than average (ranging between 25.5% and 41.9%). Since this was a pilot call, the convener’s intention was to include all relevant contributions, which explains the presence of the category type ‘other’. However, the low success rate of the contributions in this category might indicate some difficulties in their evaluation.

In the categories related to researcher training, the success rate for number of people hired is significantly lower than the average, but we found no statistical differences for the other types included in this category. Contributions to the category of knowledge transfer generating economic value (namely, licenses of intellectual property rights, patents, contracts and projects with companies and institutions and participation in active spin-off companies) show success rates significantly higher than average. However, the success rate of the contributions submitted to the category of transfer of own knowledge through activities with other institutions is significantly lower than average success rate, which might suggest that researchers were not always been able to provide documentary evidence of their activity. Also, a qualitative analysis of the contributions submitted to the category transfer of own knowledge suggests that it was poorly understood by applicants and was difficult to evaluate, possibly due to lack of precision in the call for proposals.

Among contributions to the category of transfer generating social value, the success rate for agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or public administrations for activities with special social value is significantly higher than the average, whereas the success rate for publications and dissemination activities is significantly lower than the average. However, it should be noted that, contrary to what happens in the research sexenio assessment (where the evaluators had criteria for assessing the scientific quality of journals and books in their respective fields), adopting a ‘knowledge transfer’ perspective for assessing the dissemination contributions can be challenging. The diversity of possible channels (science popularization books, reports, contributions in the media, blogs, etc.) and the difficulty involved in identifying their social relevance could contribute to this low success rate.

To sum up, we found that the types of contributions with the highest success rates were those based on commercial and formal media, such as licensing of intellectual property rights, participation in spin-off activity and contracts or agreement with external entities. The type “other” in some categories worked to lower the success rates and led to undesired dispersion and misallocation of a significant number of contributions. Among the well-defined types, publications and dissemination activities were the second most frequent type of contribution, but attracted the lowest approval rates, which justifies our more detailed analysis of these contribution types in the Study 2.

Table 210 presents the distribution of the approved contributions across types of contributions, with data disaggregated also by field (SSHA vs. STEM). The knowledge transfer activities with the highest weights across fields are contracts and projects with companies and institutions (43.6%), followed by publications and dissemination activities (13.2%) and agreements/contracts with non-profit entities and public administrations for activities with special social value (13.0%). This means that more than half of the approved contributions fall into two types—contracts and agreements with third parties.

A focus on the different fields reveals different epistemological patterns.11 Compared to STEM, SSHA includes a significantly higher proportion of approved contributions for transfer generating social value, specifically agreements/contracts with non-profit entities and public administrations (STEM: 8.0% vs. SSHA: 20.2%), publications and dissemination activities (STEM: 8.7% vs. SSHA: 19.9%), and the type ‘other’ within this category (STEM: 1.3% vs. SSHA: 5.4%). The pattern is reversed for some contributions belonging to the category of transfer generating economic value, such as number of patents (STEM: 8.8% vs. SSHA: 0.7%) and contracts and projects with companies and institutions (STEM: 49.4% vs. SSHA: 35.3%). Also, compared to STEM, SSHA has a significantly lower proportion of approved contributions for number of people hired (STEM: 11.3% vs. SSHA: 2.9%).

In combination, the results presented in Tables 1 and 2 show that publication and dissemination activities are particularly important in SSHA. However, success rates for this type of contribution are significantly lower compared to the total success rate for all the contributions submitted in response to the call. These findings, together with the gaps identified in the existing literature, suggest the need for a deeper analysis of SSHA dissemination practices to obtain a better understanding of the type of materials disseminated and their purpose. We argue that this might shed light on the low success rate observed.

5.2 SSHA dissemination patterns (Study 2)

In this section, we discuss the distribution of approved dissemination contributions according to types of dissemination output, by SSHA disciplines (Table 3) and by purpose (Table 4). We use examples of approved contributions submitted to the transfer sexenio to illustrate the type of outputs included by applicants. It should be noted that all these contributions were approved, which implies that the expert panel in the discipline or area considered that these materials had served as channels for knowledge transfer and had had some kind of impact on non-academic stakeholders.12

Figure 2 depicts the distribution of dissemination outputs approved, by SSHA discipline. We observe that the disciplines with the highest weight of approved contributions are behavioural and social sciences; arts, history and archaeology; law; and philology, linguistics and literature. 70% of the approved dissemination outputs are concentrated in the above mentioned four groups of disciplines.

Distribution (%) of dissemination outcomes by SSHA discipline.

Source: Authors based on ANECA data

Table 3 presents more detailed information on the proportions of dissemination approved contributions, by type of material, indicating whether the proportion for each discipline is significantly different from the average proportion of total SSHA (significant differences are indicated by ‘+’ or ‘−‘).13

We observe that the most frequent types of dissemination materials are scholarly books and articles aimed at non-academic audiences (52.7%), followed by reports (21.0%) and guidelines (10.1%). The other types—namely library and other virtual resources, audio-visual products and applications, mass media contributions and scientific contributions in social networks—constitute a small proportion of SSHA contributions—each of them being less than the 10% of the knowledge transfer materials submitted.

The prevalence of scholarly books and articles oriented to non-academic recipients as dissemination materials is especially noticeable in the SSHA disciplines and particularly in art, history, archaeology, philology, linguistics, and literature, where they represent more than half of the approved dissemination outputs. The data show that communication via these channels is constituted of articles in professional journals, and books oriented to a practical need or to inform a professional activity. These channels of knowledge transfer are often excluded or undervalued in evaluation processes where original research—not knowledge transfer—is the focus, but this analysis shows their value to society and the professional sector. Analysis of the type of publishing infrastructures behind these ‘not strictly academic publications’ is pending, but we would predict that they are national organizations that publish in Spanish and other languages spoken in Spain.14 These infrastructures are recognized by the Helsinki Initiative in relation to scholarly communication of science to society.

The type of dissemination material corresponding to commissioned reports is interesting and is the second most frequent dissemination output material in SSHA disciplines. Law researchers favour dissemination through reports (46.9%) rather than articles and books for non-academic readers (31.0%), which contrasts with the patterns observed in the other SSHA disciplines. Researchers in business (37.4%) and economics (29.8%) disciplines also use reports to transfer academic knowledge and use them significantly more than total SSHA. In many cases, reports are the result of direct requests from a company or organization and involve a formal contract between the parties. For these reasons, these kinds of reports and opinions are considered user-oriented dissemination enabling effective knowledge transfer at least in the aforementioned fields.

Qualitative analysis of the cases provides examples of the role played by reports in different SSHA disciplines. In the case of law, reports are often the basis for the drafting of laws, rules or regulations in various areas (finance, intellectual property, and environment). These reports are addressed to a range of stakeholders, including different units of the national and regional administrations in Spain and other countries and, among other things, support the transposition of EU directives into Spanish law and opinions on laws in the process of being approved. In business, many contributions included as reports are addressed to the competent public administration, to evaluate competitiveness, innovation and markets in particular sectors, assess the relevance of new policies to provide firm incentives and analyze the impact of existing policies. Reports produced by economists include reporting on the economic situation, employment, the economic impact of infrastructures, taxation, innovation, etc., and are addressed to public administrations, chambers of commerce and leaders of large business groups.

Guidelines, which includes codes of ethics, codes of good practice and good practice guides, are the third most frequent type of material (10.1%). This type of knowledge transfer material prevails—compared to the total SSHA field—in education (23.5%) and behavioural and social sciences (17.9%). For example, in the education field, we can identify guides and manuals related to teaching on different subjects (e.g. languages, sciences, art, sports), addressed to primary and secondary teachers, nursing professionals and social assistance (e.g. for physical or cognitive stimulation of older people or people with disabilities).

From a domain perspective, Table 3 shows that transfer patterns differ between the humanities and social sciences. They differ first in terms of their number. Approved contributions in the humanities represent over a third (37%) of total contributions, with the remaining 64% accounted for by social sciences. Second, they differ by type of dissemination output. While reports, opinion pieces, codes of good practice, etc., are important in social sciences, transfer related to humanities is in the form of media, virtual libraries, other virtual resources, and computer applications.

The number of approved contributions in the discipline of philosophy is small. In art, history, and archaeology, media and computer applications are the most frequent dissemination channels. Many of these contributions are documentary films about history and art, scientific expeditions or archaeological excavations. We also identified the use of multimedia to disseminate values (e.g. universal declaration of human rights) or the cultural heritage of towns and cities. Most involve television networks, but also include public and private local entities interested in promoting certain locations.

In philology, linguistics, and literature, virtual libraries and other virtual resources account for a higher proportion than the average SSHA field. There are many examples of online and interactive catalogues of literature, both general and specific (children, poetry), or focused on a particular author; online dictionaries of different Spanish languages or specific terms such as thesauri and other multilingual resources.

The second aspect analyzed in relation to SSHA dissemination patterns is the type of purpose. The results of the qualitative analysis of the contributions show that it is not always easy to distinguish the precise purpose (and, hence, type of audience for dissemination activities), since many materials exhibit high scientific quality and, also, have a practical orientation, making them of interest for different purposes. These outputs tend to be written for a non-expert audience. This is evidence that it can be difficult to distinguish between academic and non-academic publications (Prins et al. 2019).

Assuming these difficulties, we regrouped the contributions on six different exclusive categories according to their purpose (based on the individual narratives provided by the applicants): (1) only enlightenment; (2) only professional; (3) enlightenment and professional; (4) professional and scholarly; (5) enlightenment and scholarly; and (6) enlightenment, professional, and scholarly.

In classifying the contributions, we considered the possibility that a contribution might be used for more than one purpose, although most (76.4%) were aimed at a single type of purpose, either enlightenment (41.4%) or professional (35.0%) (Table 4).

Contributions in the form of books and articles are aimed mostly at enlightenment (58.3%), with only 15.8% for professional purposes, which is in line with previous results (Giménez Toledo et al. 2022a). It is worth noting that academic publishers in some fields (law, library science, education, etc.) publish different genres of books: essays, research monographs, books for professionals and popularization. These books generally are written by academics, based on research, published by an academic publisher and are aimed at different audience types—academic, professional, or general public. In the discussion, we address the implications of this for the evaluation.

Although not frequent, we identified cases of dissemination materials of interest to both scholars and non-scholars. These hybrid materials (Prins and Spaapen 2017) include mostly books published by prestigious national and international publishers, on economic, social, or cultural topics, describing the state of the art in the respective field and, therefore, of interest to scientists, professionals or the public. We also identified catalogues of scientific or cultural exhibitions resulting from R&D projects.

We identified material aimed at enlightenment and professional use (20.3%); general or specialized dictionaries (e.g. legal, economic, environmental); annotated editions of complete or partial works by different authors; annotated translations of works by foreign authors; books on specific diseases, including recommendations for professionals and family members; and books on topics of social interest (e.g. related to economic, demographic, political, education, industrial, or labour issues), published by prestigious commercial publishers and of interest to both professionals and the general public.

SSHA knowledge transferred via reports is mostly aimed at professional audiences and includes commissioned reports (90.3%) and guidelines (64.3%). This is expected since these types of materials are addressed to policymakers and professionals in particular sectors (education, culture, business, etc.).

In the case of codes of ethics and good practice guides (i.e. guidelines), a third of these materials are aimed at both enlightenment and professional purposes. Qualitative analysis identified examples, such as grammar and spelling books, sports guides, ways to improve cognitive ability, ways to develop communication skills and cultural heritage guides. All could be useful for professionals involved in teaching, publishing, customer services, theatre (or the cultural sector more generally), and people who want to express themselves better in a particular language, develop specific skills or learn about their cultural heritage.

In addition to transfer via non-academic publications, SSHA knowledge is transferred for enlightenment mainly through materials located in virtual libraries and other virtual resources, audio-visual products, applications, mass media contributions, and scientific contributions in social networks. These include material aimed at both the public and professionals. For example, in the case of libraries and other virtual resources, we identified specialized online dictionaries, literature and author portals, including texts and critiques, private and public archives, and tourism offers for cultural guides, administrations and also tourists. We identified portals providing information on different social services, related legislation, etc., of interest to both care professionals and care users. Examples of audio-visual products and applications include various historical, cultural, or scientific documentaries, of interest to both the public and professionals from the educational and cultural sectors. We also identified mobile phone applications to identify architectural or artistic styles. Mass media for enlightenment and professional purposes are related to participation of scientists as scientific managers, scriptwriters or content directors in regular radio or TV programmes or opinion sections in the media (press, radio, TV, etc.). We found only a few examples of scientific contributions in social networks that include both enlightenment and professional purposes, and a few blogs on legal, linguistic, and demographic topics.

6. Discussion and conclusion

The almost 40,000 contributions approved in the transfer sexenio evaluation process provide a better understanding of how scientific knowledge is transferred, the weight and relevance of the transfer channels and their success rates across STEM and SSHA. Once the dissemination materials have been identified as important elements for SSHA transfer, a more detailed analysis of these materials (almost 3,000 approved contributions) was addressed, which provided a deeper understanding of SSHA disciplinary dissemination patterns. The identification of transfer channels could be seen as one of the greatest benefits of this evaluation process, since it allows SSHA to be included in discussions of research valorization and societal impact of science and how different disciplines contribute to society, industry and institutions. Although evaluations have been conducted in the UK, Sweden, and Norway, data from the Spanish experience will allow comparison and reveal the SSHA knowledge valorization specificities.

The results show that the most successful types of contributions are those based on commercial and formal media, such as licensing of intellectual property rights, participation in spin-off activity, and contracts or agreement with external entities. To an extent, the results confirm or support existing (unmeasured) perceptions about forms of knowledge transfer in STEM fields. At the same time, they provide information on SSHA knowledge transfer. We show that the most frequent and validated (insofar as they were approved) SSHA transfer types are contracts and projects with companies and institutions (35.3% of approved contributions), agreements and/or contracts with non-profit entities or public administrations for activities with special social value (20.2%) and publications and dissemination activities (19.9%). This distinctive SSHA transfer channel profile has been identified in other social impact assessment processes (i.e. Sivertsen and Meijer 2020).

Publications and dissemination activities are important in SSHA but show lower rates of success in both SSHA and STEM fields. The importance of publications for transferring SSHA knowledge should be borne in mind by those designing evaluation policies. In future evaluations, success rates for dissemination contributions might increase were these activities to be better defined and distinguished from scholarly publications for peer-to-peer communication, which are considered in evaluations of research not linked to societal impact. In researchers’ narratives about their contributions to different societal actors and domains, providing better structured information and evidence and clearer description of the contribution (McEwan 2019; Bandola-Gill and Smith 2022) would also improve the evaluation.

Articles and books for enlightenment/professional purposes stand out among the dissemination approved contributions. It should be noted, here, that academic publishers publish different genres of books, both those oriented to researchers and those aimed at the general public or professional sectors. Therefore, in the transfer evaluation processes, this must be considered and contributions in the form of books aimed at non-academic audiences should be identified.

It is the researchers’ responsibility to submit appropriate contributions to the evaluation process and to distinguish between those aimed at an academic audience and those aimed at transferring knowledge to other audiences.

In terms of the language in which enlightenment and professional publications were published, most were in Spanish, which highlights the relevance of language in the transfer of knowledge to non-academic audiences. The role of scientific works, published in the national language, was highlighted in a report on scientific publication in Spanish and Portuguese, presented to the Ministers of Science and Technology in the Ibero-American countries (Giménez Toledo et al. 2022b).

Table 3 shows that there are evident disciplinary differences. Except for philosophy, where there are few cases of successful knowledge dissemination, different disciplines show distinctive knowledge transfer patterns.

The data confirm that SSHA researchers are producing enlightenment and professional outputs with the potential for societal impact. This is relevant information, which would need to be incorporated into the actions of scientific culture, so that this concept would systematically include research conducted in other disciplines than STEM. As Sivertsen (2022: 240) points out ‘the appearance of social scientists in these media should not be viewed as knowledge transfer only. It is participation in democratic discourse’. In this sense, promoting public communication of SSHA results would make their applied nature and their effect on society more visible.

Successful transfer of knowledge to society is essential for a scientific culture in which both science and its social aspects or effects are considered. As the humanities assumes less and less importance in secondary and higher education curricula, it would seem especially important to demonstrate its social function. It would seem vital to vindicate the social function of these disciplines, which goes beyond the transfer studied here, but includes it as a substantial part.

Public dissemination of specific cases would promote knowledge exchange and knowledge transfer by SSHA researchers. Researchers—and the research system as a whole—should consider how to contribute to social challenges, which, in many cases, implies thinking about and taking part in interdisciplinary forms of exchange and transfer of knowledge to facilitate collaboration among different disciplines, in order to address social problems in an integrated manner (Spaapen and Sivertsen 2020). The Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) is making efforts in this direction through its Interdisciplinary Thematic Platforms,15 defined as ‘partnerships in scientific collaboration for a social mission and tomorrow’s solutions’, and The White Books for Scientific Challenges 2030,16 which defines future research priorities and needs, considering the Sustainable Development Goals17 and global societal issues.

Analysis of the sexenio data shows how scientific knowledge is transferred to society and, similar to the UK REF exercise, the impact case studies serve ‘to identify pathways, beneficiaries, and effects of research in the reported cases’ (Sivertsen and Meijer 2020: 68). Sivertsen and Meijer analyze the interaction between academia and institutions on a day-to-day basis and suggest that societal needs should be the starting point for academics (see also Olmos-Peñuela, Benneworth and Castro-Martínez 2015b).

The results of the present study allow us to reflect, also, on the value each country assigns to books and journals. The Helsinki Initiative on Multilingualism in Science Communication18 emphasizes the value of editorial structures and different languages for bringing scientific knowledge to society, calling for multilingualism in the connection between science and society. In addition to scientific publications, whose main objective is to publicize original research results and allow exchanges of knowledge among specialists, some publications disseminate knowledge to professionals, institutions and enterprises. Our findings show that written media are important for knowledge transfer, which highlights the need to consider the editorial structures enabling this function. Hence, editorial structures should be the object of attention of both book and evaluation policies and their coordination.

Finally, we show that reports, guides, protocols, codes, etc. are important channels of knowledge. They tend to be produced with the collaboration of interested institutions or groups, in the collective construction of knowledge useful to a particular sector. Their value is confirmed by the transfer sexenio evaluation exercise. It should be extrapolated to other accreditation processes and to the evaluation processes of academic institutions.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Research Evaluation Journal online.

Acknowledgement