-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Melinda Craike, Bojana Klepac, Amy Mowle, Therese Riley, Theory of systems change: An initial, middle-range theory of public health research impact, Research Evaluation, Volume 32, Issue 3, July 2023, Pages 603–621, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvad030

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

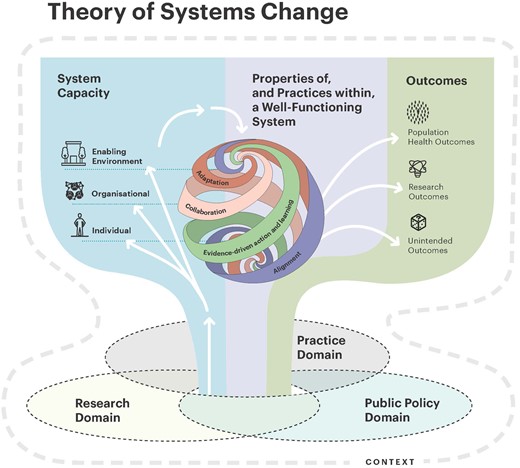

There is increasing attention on evidencing research impact and applying a systems thinking perspective in public health. However, there is limited understanding of the extent to which and how public health research that applies a systems thinking perspective contributes to changes in system behaviour and improved population health outcomes. This paper addresses the theoretical limitations of research impact, theory-based evaluation and systems thinking, by drawing on their respective literature to develop an initial, middle-range Theory of Systems Change, focused on the contribution of public health research that takes a systems perspective on population health outcomes. The Theory of Systems Change was developed through four phases: (1) Preliminary activities, (2) Theory development, (3) Scripting into images, and (4) Examining against Merton’s criteria. The primary propositions are: that well-functioning systems create the conditions for improved population health outcomes; the inter-related properties of, and practices within, well-functioning systems include adaptation, alignment, collaboration and evidence-driven action and learning; and public health research contributes to population health outcomes by embedding capacity in the system. The Theory of Systems Change can guide researchers in developing project-specific theories of change and creates the theoretical architecture for the accumulation of learning. The Theory of Systems Change is necessarily incomplete and an initial attempt to develop a theory to be scrutinized and tested. Ultimately, it seeks to advance theory and provide evidence-based guidance to maximize the contribution of research. We provide examples of how we have applied the Theory of Systems Change to Pathways in Place.

Background

Public health research focuses on improving population health outcomes by addressing the determinants of health, such as access to quality healthcare, social determinants (e.g. education and employment) and health behaviours (e.g. diet and physical activity) (Braveman and Gottlieb 2014; Short and Mollborn 2015). There is increasing acknowledgement that these determinants are complex problems because they are unpredictable, intractable (Alford and Head 2017) and the product of interactions within complex systems (Rutter et al. 2017). Consequently, like other fields, public health is moving away from reductionist, linear approaches targeted at individual-level change towards applying a systems thinking perspective that embraces complexity and seeks systems-level change to improve population health outcomes (Rutter et al. 2017). In parallel to the increased application of a system thinking perspective, there is increasing attention on demonstrating the impact of research beyond academia as governments and research funders seek to establish the benefits of research for improved societal outcomes (Martin 2011; Hill 2016; Oancea 2019; Boulding et al. 2020).

Despite the increasing attention on systems thinking perspectives and research impact, these literatures are rarely bought together and there is limited understanding of the extent to which and how public health research that applies a systems perspective contributes to changes in system behaviour and improved population health outcomes. We argue that researchers must bring these literatures together and address their theoretical limitations to guide research evaluation and advance knowledge. This can be achieved by developing a middle-range theory of systems change that integrates theory and empirical evidence from these and other relevant disciplines and fields.

In 1949, Robert Merton first wrote about the need for middle-range theories—those which ‘… lie between the minor but necessary working hypotheses that evolve in abundance during day-to-day research and the all-inclusive systematic efforts to develop a unified theory …’ (Merton 1968: 39–40). Merton proposed that there was a middle ground between grand theories (such as General Systems Theory) and the technical categorization of empirical data. He argued that middle-range theories can provide the links between empirical observations and grand theory by creating boundaries (or assumptions) about a field of interest that can generate propositions and be empirically tested. We draw on the concerns of Merton (Merton 1968; Blaikie 2000) because we believe they are reflected in the challenges we currently face in the theoretical limitations of our fields of interest—research impact and translation, theory-based evaluation and systems thinking. The juxtaposed pursuits of impact metrics and grand statements of societal gains dog the field of research impact. Neither advances theoretical understanding about the role of research in a dynamic complex system.

Although several models of research impact have been developed to demonstrate the societal benefits of research (Milat, Bauman and Redman 2015; Razmgir et al. 2021), these models have several limitations. Models of research impact often assume a linear progression from inputs to societal outcomes; are atheoretical, comprising lists of disconnected concepts that are not linked to higher level theory nor make explicit the links between the research process, its application and contribution to societal outcomes. Many models of research impact are based on the often untested or contested assumption that research-informed policy and practice will improve societal outcomes (Milat, Bauman and Redman 2015; Parkhurst and Abeysinghe 2016).

There is an evolving interest in research evaluation to both evidence and understand research impact (Belcher, Suryadarma and Halimanjaya 2017). Theory-based evaluation, which is prevalent in public health literature (Connell and Kubisch 1998; Breuer et al. 2016), is increasingly used in research evaluation because it facilitates an understanding of the extent to which and how research contributes to societal outcomes (such as population health outcomes) (DuBow and Litzler 2019; Belcher, Davel and Claus 2020; Deutsch et al. 2021). Theory-based evaluation usually involves three key components: (1) the development of a theory of change (MARLO 2015; Belcher et al. 2018); (2) data collection to see whether and to what magnitude the expected changes have occurred; and (3) an examination of the links between the changes to test assumptions and to confirm or reject the theory (Upton, Vallance and Goddard 2014). The few published theories of change in the research evaluation literature are project-specific (Belcher, Suryadarma and Halimanjaya 2017; DuBow and Litzler 2019). This level of specificity precludes systemic understanding of how research contributes to societal outcomes because the theories of change are tied so closely to the ‘particulars’ of research projects that they lose their capacity to guide future inquiry, contribute to a body of knowledge, or generate new propositions in different contexts (Bonell et al. 2023).

Systems scholars are at a similar impasse in applying systems thinking to public health research inquiry. There is a growing momentum to apply systems thinking in public health research—moving from a rallying cry (Carey et al. 2015b; Rutter et al. 2017) to the application of systems methods when examining complex problems such as the social determinants of health (McGill et al. 2021). Much of the effort is focused on what new or additional insights into complex problems come from applying systems methods, such as dynamic simulation modelling or causal loop diagrams (McGlashan et al. 2016; Riley et al. 2021a). Here, systems theory and concepts are being applied and tested using methods that reflect the theory. However, a recent review of evaluations of public health interventions that take a systems perspective did find the application of systems concepts to be (at times) theoretically inconsistent (McGill et al. 2020). This focus on testing the theory (while providing new and helpful insights into complex problems) has resulted in new frameworks and theoretical taxonomies demonstrating the value of systems theory (Leykum et al. 2007; McGill et al. 2020).

Merton argued that grand social (or, in our case, systems) theory was too remote from the social and system behaviour we observe through research and, as such, risk having a ‘retarding effect’ on the advancement of knowledge (Merton 1968; Blaikie 2000). Importantly, these grand theories and concepts are too abstract to guide research inquiry—a common challenge faced by researchers and practitioners applying systems thinking (Bensberg 2021). Middle-range theories of change can accommodate and connect multiple theoretical perspectives and overcome the limitations of the atheoretical and project-specific approaches that dominate research impact, knowledge translation, and theory-based evaluation literature, and the ‘grand theories’ that dominate the systems thinking literature. If we are to move away from accumulating disparate and disconnected frameworks to theoretical knowledge from which to guide inquiry, learn and generate new propositions, we must build middle-range theories of change in a Mertonian sense and hold ourselves to account (Merton 1968; Blaikie 2000).

In this paper, we advance the research impact, knowledge translation, theory-based evaluation, systems thinking and public health literature by introducing a new middle-range theory of change, which we refer to as the Theory of Systems Change. The Theory of Systems Change is an initial attempt to advance knowledge about the extent to which and how public health research that takes a systems perspective contributes to population health outcomes. A systems perspective guides all levels of the theory, from research practice to understanding system and population-level change. The Theory of Systems Change can be a guide for other projects in developing their own theory of change (Shearn et al. 2017) and creates the theoretical architecture to build a coherent body of knowledge about the extent to which and how research that takes a systems perspective contributes to population health outcomes. We provide examples of the application of the Theory of Systems Change to a ‘real life’ research programme, called Pathways in Place.

Pathways in place

Funded by the Paul Ramsay Foundation, Pathways in Place (www.pathwaysinplace.com.au) is a 5-year research programme comprised of a series of interconnected projects. Commencing in August 2020, Pathways in Place is jointly led by two research teams based at two Australian universities in Queensland and Victoria (Griffith University and Victoria University, respectively). Pathways in Place focuses on two life stages, aiming to strengthen and optimize: (1) Early learning and development pathways (children and young people aged 0–15); and (2) Pathways through education to employment (young people aged 15–24). Pathways in Place takes a place-based, systems change approach and as such projects are bound geographically according to local government areas. While we predominately work with partner communities and local government bodies in the City of Brimbank in Melbourne, Victoria, and the City of Logan, Queensland, we also work with, and scale out our research to other communities in Australia and internationally. The work of Pathways in Place across both Universities is guided by a set of principles, a commitment to co-creation, and an overarching framework.

The Theory of Systems Change, the focus of this paper, was developed by and guides the work of the Pathways in Place-Victoria University (www.pathwaysinplace.com.au/victoria-university) team. Pathways in Place-Victoria University simultaneously develops the evidence-base for place-based, systems change approaches and builds capacity to support the design and implementation of effective place-based, systems change approaches to improve population health outcomes. All Pathways in Place-Victoria University projects align with the Theory of Systems Change. See Supplementary File S1 for more details about Pathways in Place.

Approach and methods

There is no one standard approach to developing a middle-range theory. Various approaches and methods have been used in theory development (Liehr and Smith 1999; Shearn et al. 2017). Our approach to developing the Theory of Systems Change included four phases.

Phase 1: Preliminary activities

Preliminary activities involved co-creating the funding proposal with researchers, practitioners, and the funder, whose purpose is to ‘help end cycles of disadvantage in Australia by enabling equitable opportunity for people and communities to thrive’ (Paul Ramsay Foundation 2023). We then conducted workshops and meetings with the Pathways in Place team and the programme’s leadership group. Based on these preliminary activities, we identified the funder’s priorities, the expertise of the research team, and existing research partnerships, which informed the scope for the Theory System Change. The Theory of Systems Change: adopts a place-based, systems change approach; identifies the role of research in place-based systems change; and includes a focus on collaboration across disciplinary and sector boundaries.

Phase 2: Theory development

In the theory development phase, the authorship team engaged in (1) backwards mapping, (2) proposition development, and (3) conceptualizing the main terms in the theory.

Backwards mapping: Backwards mapping begins with long-term outcomes and works ‘backwards’ towards the earliest changes that need to occur (Center for Theory of Change 2023). For the Theory of Systems Change, the main components of backwards mapping included:

Defining the desired long-term research and societal outcomes.

Determining the inter-related properties and practices of a well-functioning system that would lead to improved population health outcomes. We sought to identify practices that were both applicable across systems to address different problems for different target populations and applicable across research, practice, and public policy domains.

Determining the conditions that support these practices in the long-term. Sustainability is necessary for practices to become properties of the system. We identified system capacity as central to support sustainable practice.

Focusing on the ‘research’ domain and determining the role of research in embedding capacity into the system. This included determining the pathways through which research contributes to embedding system capacity, the attributes of research that would lead to these outcomes, and how these interact with the practices of a well-functioning system.

Considering the pre-conditions across research, practice, and public policy that influence the ability of research to embed capacity into the system.

Considering the relationships between the aforementioned components of backwards mapping, including how they reinforce or strengthen each other.

These components provided a framework for data collection and analysis. Through a dynamic and iterative process, we cycled between deduction from existing theories and evidence, and induction from the experiences of other researchers, practitioners and public policy-makers, and our own research findings and practice.

We conducted multiple literature scans to identify theories, frameworks, models, and empirical evidence across various disciplines and fields. We engaged in theoretical and empirical integration and synthesis to address each of the components of backwards mapping. We predominantly drew on public health, systems thinking, research impact and knowledge translation literature (which themselves draw on a range of disciplinary perspectives). We also drew on complementary literature from education, community development, developmental psychology, transdisciplinary research, implementation science, sustainability science, behavioural science, sociology, communication research, and political science.

We engaged in (1) formal (e.g. workshops, written feedback, meetings) and informal (e.g. informal discussions) engagement with practitioners, policy-makers and researchers both nationally and internationally, and (2) research team reflective practice sessions, where we reflected on our early research experiences and findings in Pathways in Place-Victoria University. Drawing on our learnings from the literature scans we discussed our own experiences to synthesize our perspectives and surface our assumptions in a dialogic process akin to that espoused by Schultz (Schutz 1953; Blaikie 2000).

2) Development of propositions: We developed a series of propositions related to the components above, based on our learnings from the deductive and inductive synthesis. Consistent with middle-range theory, we developed propositions that are empirically testable but general enough to be tested across different contexts (Merton 1968).

3) Conceptualizing key terms: Conceptualizing key terms is essential to theory development to provide a common understanding of the language used (Liehr and Smith 1999; Varpio et al. 2020; Bonell et al. 2023). Conceptualizing key terms is particularly important when engaging with literature and theory from a range of disciplines, which sometimes use different conceptualizations for the same term. We adopted conceptualizations that are consistent with our approach (place-based, systems change) and field (public health). When we were unable to find an existing conceptualization that was fit for our purpose, we adapted existing conceptualizations, or created our own. A glossary of key terms and their conceptualizations is in Table 1.

| Terms . | Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Capacity | Capacity is the ability of individuals, organizations or broader systems to perform appropriate functions and address issues and concerns effectively, efficiently, and sustainably (Milèn 2001). |

| Context | Context refers to ‘the circumstances or events that form the environment within which something exists or takes place and as that which therefore helps make phenomena intelligible and meaningful’ (Poland et al. 2006: 59). |

| Embedding capacity into the system | Embedding capacity in the system requires intentionally building the individual, organizational, and enabling environment dimensions of capacity across research, practice, and public policy, and strengthening relationships within and between the dimensions and domains. |

| Enabling environment | Enabling environment includes a set of interrelated conditions—such as public policy, legal, bureaucratic, fiscal, informational, political, and cultural—that influence the capacity of researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers to practice adaptation, alignment, collaboration and evidence-driven action and learning in a sustained and effective manner (adapted from: World Bank 2003). |

| Middle-range theory | Middle-range theory ‘is an implicit or explicit explanatory theory’ that can be utilized to assess projects, programmes, and/or interventions. ‘“Middle-range” means that it can be tested with the observable data and is not abstract to the point of addressing larger social or cultural forces’ (Jagosh et al. 2012: 316). |

| Population health outcomes | Population health outcomes refer to the overall health status and outcomes of a group (i.e. subpopulation) or whole population (e.g. within one country) and generally includes measures such as disease incidence, mortality rates, and quality of life. |

| Practice domain | Practice domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) practitioners, that is, individuals who work directly with the target populations through service or programme delivery and/or those in managerial or leadership positions who are in a position to influence organizational cultural change and the systems and structures within their organizations (Jansen et al. 2010); (2) other individuals (e.g. administrative staff) working in practice-focused organizations; (3) practice-focused organizations, that is, organizations whose main aims are to serve the needs of others, either directly or indirectly (Jansen et al. 2010), practically apply or implement knowledge, research, skills, and procedures in a particular field, and engage in activities associated with developing, organizing and/or delivering services or programmes, that employ above mentioned individuals (e.g. not for profit organizations, charities); (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal organizational policy on ethical misconduct); and (5) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within practice-focused organizations. |

| Public policy domain | Public policy domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) policy-makers, that is, individuals engaged in the process of developing, enacting, implementing and/or evaluating public policies; (2) other individuals working in a public authority/government department or agency (e.g. administrative staff); (3) organizations that employ these individuals, that is, a public authority/government department or agency; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal departmental policy on ethical misconduct); (5) public policies (i.e. a ‘purposive courses of action’ (Anderson 1984: 3) most commonly presented in the form of an officially endorsed written document, that aim to solve a particular public issue or a matter of concern, typically developed, enacted or implemented by a public authority or authorities) that shape practices of individuals and organizations in other domains (e.g. federal government policy on funding universities—the Research domain); and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within a public authority/government department or agency. |

| Research domain | Research domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) researchers, that is individuals who conduct academic (also called scientific or scholarly) research (i.e. type of research that undergoes peer-reviewed process that seeks to shift understanding and advance academic methods, theories and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022)); (2) other individuals working in a research organization such as research institute or a university (e.g. administrative staff and senior executives); (3) research organizations that employ these individuals; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. University policy on ethical misconduct); (5) research knowledge (i.e. also referred as scholarly, academic, or scientific refers to type of knowledge that is ‘intersubjective-shared among experts’ (Miettinen, 2001), usually undertaken in a research organization and undergoes peer-reviewed process. It can be conceptualized as an outcome of a systematic and disciplined approach to inquiry that generally includes collecting, analysing, and interpreting the data to develop new or advance existing concepts, insights, theories, methods, processes or applications; and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within above mentioned research organizations such as universities and research institutes. |

| Research outcomes | Research outcomes are the demonstrable contribution that research makes in shifting understanding and advancing academic (i.e. scientific or scholarly) methods, theories, and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022). |

| System | ‘A set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its “function” or “purpose”’ (Meadows 2008: 188). In the context of the Theory of Systems Change, we elaborate on this definition and conceptualize a ‘system’ as the environment within which the target population lives and grows, comprising a range of subsystems that directly and/or indirectly influence on the health of the target population (Zaff et al. 2015a). |

| Unintended outcomes | Unintended outcomes are effects that research can have other than those it originally intended to achieve, that can be both positive and negative. |

| Terms . | Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Capacity | Capacity is the ability of individuals, organizations or broader systems to perform appropriate functions and address issues and concerns effectively, efficiently, and sustainably (Milèn 2001). |

| Context | Context refers to ‘the circumstances or events that form the environment within which something exists or takes place and as that which therefore helps make phenomena intelligible and meaningful’ (Poland et al. 2006: 59). |

| Embedding capacity into the system | Embedding capacity in the system requires intentionally building the individual, organizational, and enabling environment dimensions of capacity across research, practice, and public policy, and strengthening relationships within and between the dimensions and domains. |

| Enabling environment | Enabling environment includes a set of interrelated conditions—such as public policy, legal, bureaucratic, fiscal, informational, political, and cultural—that influence the capacity of researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers to practice adaptation, alignment, collaboration and evidence-driven action and learning in a sustained and effective manner (adapted from: World Bank 2003). |

| Middle-range theory | Middle-range theory ‘is an implicit or explicit explanatory theory’ that can be utilized to assess projects, programmes, and/or interventions. ‘“Middle-range” means that it can be tested with the observable data and is not abstract to the point of addressing larger social or cultural forces’ (Jagosh et al. 2012: 316). |

| Population health outcomes | Population health outcomes refer to the overall health status and outcomes of a group (i.e. subpopulation) or whole population (e.g. within one country) and generally includes measures such as disease incidence, mortality rates, and quality of life. |

| Practice domain | Practice domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) practitioners, that is, individuals who work directly with the target populations through service or programme delivery and/or those in managerial or leadership positions who are in a position to influence organizational cultural change and the systems and structures within their organizations (Jansen et al. 2010); (2) other individuals (e.g. administrative staff) working in practice-focused organizations; (3) practice-focused organizations, that is, organizations whose main aims are to serve the needs of others, either directly or indirectly (Jansen et al. 2010), practically apply or implement knowledge, research, skills, and procedures in a particular field, and engage in activities associated with developing, organizing and/or delivering services or programmes, that employ above mentioned individuals (e.g. not for profit organizations, charities); (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal organizational policy on ethical misconduct); and (5) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within practice-focused organizations. |

| Public policy domain | Public policy domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) policy-makers, that is, individuals engaged in the process of developing, enacting, implementing and/or evaluating public policies; (2) other individuals working in a public authority/government department or agency (e.g. administrative staff); (3) organizations that employ these individuals, that is, a public authority/government department or agency; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal departmental policy on ethical misconduct); (5) public policies (i.e. a ‘purposive courses of action’ (Anderson 1984: 3) most commonly presented in the form of an officially endorsed written document, that aim to solve a particular public issue or a matter of concern, typically developed, enacted or implemented by a public authority or authorities) that shape practices of individuals and organizations in other domains (e.g. federal government policy on funding universities—the Research domain); and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within a public authority/government department or agency. |

| Research domain | Research domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) researchers, that is individuals who conduct academic (also called scientific or scholarly) research (i.e. type of research that undergoes peer-reviewed process that seeks to shift understanding and advance academic methods, theories and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022)); (2) other individuals working in a research organization such as research institute or a university (e.g. administrative staff and senior executives); (3) research organizations that employ these individuals; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. University policy on ethical misconduct); (5) research knowledge (i.e. also referred as scholarly, academic, or scientific refers to type of knowledge that is ‘intersubjective-shared among experts’ (Miettinen, 2001), usually undertaken in a research organization and undergoes peer-reviewed process. It can be conceptualized as an outcome of a systematic and disciplined approach to inquiry that generally includes collecting, analysing, and interpreting the data to develop new or advance existing concepts, insights, theories, methods, processes or applications; and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within above mentioned research organizations such as universities and research institutes. |

| Research outcomes | Research outcomes are the demonstrable contribution that research makes in shifting understanding and advancing academic (i.e. scientific or scholarly) methods, theories, and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022). |

| System | ‘A set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its “function” or “purpose”’ (Meadows 2008: 188). In the context of the Theory of Systems Change, we elaborate on this definition and conceptualize a ‘system’ as the environment within which the target population lives and grows, comprising a range of subsystems that directly and/or indirectly influence on the health of the target population (Zaff et al. 2015a). |

| Unintended outcomes | Unintended outcomes are effects that research can have other than those it originally intended to achieve, that can be both positive and negative. |

| Terms . | Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Capacity | Capacity is the ability of individuals, organizations or broader systems to perform appropriate functions and address issues and concerns effectively, efficiently, and sustainably (Milèn 2001). |

| Context | Context refers to ‘the circumstances or events that form the environment within which something exists or takes place and as that which therefore helps make phenomena intelligible and meaningful’ (Poland et al. 2006: 59). |

| Embedding capacity into the system | Embedding capacity in the system requires intentionally building the individual, organizational, and enabling environment dimensions of capacity across research, practice, and public policy, and strengthening relationships within and between the dimensions and domains. |

| Enabling environment | Enabling environment includes a set of interrelated conditions—such as public policy, legal, bureaucratic, fiscal, informational, political, and cultural—that influence the capacity of researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers to practice adaptation, alignment, collaboration and evidence-driven action and learning in a sustained and effective manner (adapted from: World Bank 2003). |

| Middle-range theory | Middle-range theory ‘is an implicit or explicit explanatory theory’ that can be utilized to assess projects, programmes, and/or interventions. ‘“Middle-range” means that it can be tested with the observable data and is not abstract to the point of addressing larger social or cultural forces’ (Jagosh et al. 2012: 316). |

| Population health outcomes | Population health outcomes refer to the overall health status and outcomes of a group (i.e. subpopulation) or whole population (e.g. within one country) and generally includes measures such as disease incidence, mortality rates, and quality of life. |

| Practice domain | Practice domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) practitioners, that is, individuals who work directly with the target populations through service or programme delivery and/or those in managerial or leadership positions who are in a position to influence organizational cultural change and the systems and structures within their organizations (Jansen et al. 2010); (2) other individuals (e.g. administrative staff) working in practice-focused organizations; (3) practice-focused organizations, that is, organizations whose main aims are to serve the needs of others, either directly or indirectly (Jansen et al. 2010), practically apply or implement knowledge, research, skills, and procedures in a particular field, and engage in activities associated with developing, organizing and/or delivering services or programmes, that employ above mentioned individuals (e.g. not for profit organizations, charities); (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal organizational policy on ethical misconduct); and (5) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within practice-focused organizations. |

| Public policy domain | Public policy domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) policy-makers, that is, individuals engaged in the process of developing, enacting, implementing and/or evaluating public policies; (2) other individuals working in a public authority/government department or agency (e.g. administrative staff); (3) organizations that employ these individuals, that is, a public authority/government department or agency; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal departmental policy on ethical misconduct); (5) public policies (i.e. a ‘purposive courses of action’ (Anderson 1984: 3) most commonly presented in the form of an officially endorsed written document, that aim to solve a particular public issue or a matter of concern, typically developed, enacted or implemented by a public authority or authorities) that shape practices of individuals and organizations in other domains (e.g. federal government policy on funding universities—the Research domain); and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within a public authority/government department or agency. |

| Research domain | Research domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) researchers, that is individuals who conduct academic (also called scientific or scholarly) research (i.e. type of research that undergoes peer-reviewed process that seeks to shift understanding and advance academic methods, theories and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022)); (2) other individuals working in a research organization such as research institute or a university (e.g. administrative staff and senior executives); (3) research organizations that employ these individuals; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. University policy on ethical misconduct); (5) research knowledge (i.e. also referred as scholarly, academic, or scientific refers to type of knowledge that is ‘intersubjective-shared among experts’ (Miettinen, 2001), usually undertaken in a research organization and undergoes peer-reviewed process. It can be conceptualized as an outcome of a systematic and disciplined approach to inquiry that generally includes collecting, analysing, and interpreting the data to develop new or advance existing concepts, insights, theories, methods, processes or applications; and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within above mentioned research organizations such as universities and research institutes. |

| Research outcomes | Research outcomes are the demonstrable contribution that research makes in shifting understanding and advancing academic (i.e. scientific or scholarly) methods, theories, and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022). |

| System | ‘A set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its “function” or “purpose”’ (Meadows 2008: 188). In the context of the Theory of Systems Change, we elaborate on this definition and conceptualize a ‘system’ as the environment within which the target population lives and grows, comprising a range of subsystems that directly and/or indirectly influence on the health of the target population (Zaff et al. 2015a). |

| Unintended outcomes | Unintended outcomes are effects that research can have other than those it originally intended to achieve, that can be both positive and negative. |

| Terms . | Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Capacity | Capacity is the ability of individuals, organizations or broader systems to perform appropriate functions and address issues and concerns effectively, efficiently, and sustainably (Milèn 2001). |

| Context | Context refers to ‘the circumstances or events that form the environment within which something exists or takes place and as that which therefore helps make phenomena intelligible and meaningful’ (Poland et al. 2006: 59). |

| Embedding capacity into the system | Embedding capacity in the system requires intentionally building the individual, organizational, and enabling environment dimensions of capacity across research, practice, and public policy, and strengthening relationships within and between the dimensions and domains. |

| Enabling environment | Enabling environment includes a set of interrelated conditions—such as public policy, legal, bureaucratic, fiscal, informational, political, and cultural—that influence the capacity of researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers to practice adaptation, alignment, collaboration and evidence-driven action and learning in a sustained and effective manner (adapted from: World Bank 2003). |

| Middle-range theory | Middle-range theory ‘is an implicit or explicit explanatory theory’ that can be utilized to assess projects, programmes, and/or interventions. ‘“Middle-range” means that it can be tested with the observable data and is not abstract to the point of addressing larger social or cultural forces’ (Jagosh et al. 2012: 316). |

| Population health outcomes | Population health outcomes refer to the overall health status and outcomes of a group (i.e. subpopulation) or whole population (e.g. within one country) and generally includes measures such as disease incidence, mortality rates, and quality of life. |

| Practice domain | Practice domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) practitioners, that is, individuals who work directly with the target populations through service or programme delivery and/or those in managerial or leadership positions who are in a position to influence organizational cultural change and the systems and structures within their organizations (Jansen et al. 2010); (2) other individuals (e.g. administrative staff) working in practice-focused organizations; (3) practice-focused organizations, that is, organizations whose main aims are to serve the needs of others, either directly or indirectly (Jansen et al. 2010), practically apply or implement knowledge, research, skills, and procedures in a particular field, and engage in activities associated with developing, organizing and/or delivering services or programmes, that employ above mentioned individuals (e.g. not for profit organizations, charities); (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal organizational policy on ethical misconduct); and (5) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within practice-focused organizations. |

| Public policy domain | Public policy domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) policy-makers, that is, individuals engaged in the process of developing, enacting, implementing and/or evaluating public policies; (2) other individuals working in a public authority/government department or agency (e.g. administrative staff); (3) organizations that employ these individuals, that is, a public authority/government department or agency; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. internal departmental policy on ethical misconduct); (5) public policies (i.e. a ‘purposive courses of action’ (Anderson 1984: 3) most commonly presented in the form of an officially endorsed written document, that aim to solve a particular public issue or a matter of concern, typically developed, enacted or implemented by a public authority or authorities) that shape practices of individuals and organizations in other domains (e.g. federal government policy on funding universities—the Research domain); and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within a public authority/government department or agency. |

| Research domain | Research domain encompasses the following components, as well as the interrelationships between them: (1) researchers, that is individuals who conduct academic (also called scientific or scholarly) research (i.e. type of research that undergoes peer-reviewed process that seeks to shift understanding and advance academic methods, theories and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022)); (2) other individuals working in a research organization such as research institute or a university (e.g. administrative staff and senior executives); (3) research organizations that employ these individuals; (4) policies/processes/procedures that shape practices of individuals and organizations within this domain (e.g. University policy on ethical misconduct); (5) research knowledge (i.e. also referred as scholarly, academic, or scientific refers to type of knowledge that is ‘intersubjective-shared among experts’ (Miettinen, 2001), usually undertaken in a research organization and undergoes peer-reviewed process. It can be conceptualized as an outcome of a systematic and disciplined approach to inquiry that generally includes collecting, analysing, and interpreting the data to develop new or advance existing concepts, insights, theories, methods, processes or applications; and (6) power dynamics, politics, and tacit values and norms embedded within above mentioned research organizations such as universities and research institutes. |

| Research outcomes | Research outcomes are the demonstrable contribution that research makes in shifting understanding and advancing academic (i.e. scientific or scholarly) methods, theories, and knowledge across and within disciplines (adapted from the definition of ‘academic outcomes’ by Economic and Social Research Council 2022). |

| System | ‘A set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its “function” or “purpose”’ (Meadows 2008: 188). In the context of the Theory of Systems Change, we elaborate on this definition and conceptualize a ‘system’ as the environment within which the target population lives and grows, comprising a range of subsystems that directly and/or indirectly influence on the health of the target population (Zaff et al. 2015a). |

| Unintended outcomes | Unintended outcomes are effects that research can have other than those it originally intended to achieve, that can be both positive and negative. |

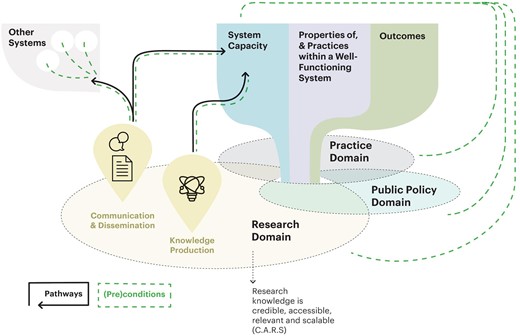

Phase 3: Scripting the theory of systems change into images

Based on the propositions, we worked with a graphic artist to script the Theory of Systems Change into images. The development of images served two purposes. The first was analytic integration, whereby the images were used as a complementary reflexivity strategy to better understand the concepts and relationships within the Theory of Systems Change. The second was visual communication and representation of the Theory of Systems Change (Archibald and Gerber 2018). Although our original intention was to develop a single image, we realized that the complexity of the Theory of Systems Change required two complementary images—the first representing the ‘overarching’ theory, and the second focused on the role of research in improving population health outcomes.

Phase 4: Examining the theory of systems change against the criteria developed by Merton

To ensure we remained true to Merton’s (Merton 1968) conceptualization of middle-range theory, we examined the Theory of Systems Change against the following criteria:

Does it include assumptions from which propositions can be developed and empirically tested?

Does it exist in relationship to other (including grand) theories?

Is it ‘sufficiently abstract’ (Blaikie 2000: 147) to be applied in other contexts or situations?

Does it cut across macro and micro social problems?

Does it include the ‘specification of ignorance’ (Blaikie 2000:148)—what is not known or still to be learned?

Theory of systems change

In this section, we first provide an overview of the Theory of Systems Change. Following this, we describe the Theory of Systems Change according to its various components, working backwards from outcomes. We include propositions and the literature and theory that have informed the propositions and describe how each component relates to other components of the Theory of Systems Change. Collated central propositions and main literature and theories supporting the propositions are available in Supplementary File S2.

Overview

According to the Theory of Systems Change, a target population’s health outcomes result from complex interactions with the ‘system’ in which they live and grow. Well-functioning systems create the conditions for improved population health outcomes for current and future generations. Four inter-related properties of and practices within research, practice, and public policy characterize well-functioning systems. These are: (1) engagement in evidence-driven action and learning; (2) adaptation to external opportunities and challenges; (3) alignment with the strengths and needs of the target population, across all levels of the system; and (4) collaboration. A well-functioning system is predicated on system capacity to engage in these practices. Embedding capacity in the system requires intentionally building the individual, organizational and enabling environment dimensions of capacity across research, practice, and public policy, and strengthening relationships within and between the dimensions and domains. For a graphic illustration, see Figure 1.

Theory of systems change. Illustration by Kirsten Moegerlein (https://kirstenmoegerlein.com/).

Public health research can contribute to population health outcomes by embedding capacity in the system. The pathways through which public health research can embed capacity are by involving practitioners and policy-makers in the process of knowledge production and through the communication and dissemination of research knowledge. To embed capacity within and across systems, research knowledge needs to be credible, accessible, relevant, and scalable. When researchers engage in the practices of a well-functioning system, they are likely to produce research knowledge with these attributes. There are pre-conditions that influence the effectiveness of research at embedding system capacity. These preconditions include the capacity of researchers, practitioners, and public policy-makers to engage in practices of a well-functioning system. For a graphic illustration, see Figure 2.

Research domain—embedding system capacity. Illustration by Kirsten Moegerlein (https://kirstenmoegerlein.com/).

A glossary of key terms in the Theory of Systems Change are in Table 1. Applications of the Theory of Systems Change to Pathways in Place-Victoria University are in Tables 2–8.

Application to Pathways in Place-Victoria University: desired and unintended outcomes

| Research outcomes |

|

| Population health outcomes |

|

| Unintended outcomes |

|

| Research outcomes |

|

| Population health outcomes |

|

| Unintended outcomes |

|

Application to Pathways in Place-Victoria University: desired and unintended outcomes

| Research outcomes |

|

| Population health outcomes |

|

| Unintended outcomes |

|

| Research outcomes |

|

| Population health outcomes |

|

| Unintended outcomes |

|

| System of relevance |

|

| System of relevance |

|

| System of relevance |

|

| System of relevance |

|

Application to Pathways in Place-Victoria University: evidence-driven action and learning

| Evidence-driven action and learning . | Examples . |

|---|---|

Situation analysis and problem identification

| |

Coordinated actions

| |

Monitoring and evaluation

| |

Communication and dissemination

|

| Evidence-driven action and learning . | Examples . |

|---|---|

Situation analysis and problem identification

| |

Coordinated actions

| |

Monitoring and evaluation

| |

Communication and dissemination

|

Application to Pathways in Place-Victoria University: evidence-driven action and learning

| Evidence-driven action and learning . | Examples . |

|---|---|

Situation analysis and problem identification

| |

Coordinated actions

| |

Monitoring and evaluation

| |

Communication and dissemination

|

| Evidence-driven action and learning . | Examples . |

|---|---|

Situation analysis and problem identification

| |

Coordinated actions

| |

Monitoring and evaluation

| |

Communication and dissemination

|

| Adaptation | Examples

|

| Adaptation | Examples

|

| Adaptation | Examples

|

| Adaptation | Examples

|

| Alignment | Examples

|

| Alignment | Examples

|

| Alignment | Examples

|

| Alignment | Examples

|

| Collaboration | Examples

|

| Collaboration | Examples

|

| Collaboration | Examples

|

| Collaboration | Examples

|

Application to Pathways in Place-Victoria University: building capacity for evidence-driven action and learning

| Building capacity for evidence-driven action and learning | Examples (related to Situation analysis and problem identification):

|

| Building capacity for evidence-driven action and learning | Examples (related to Situation analysis and problem identification):

|

Application to Pathways in Place-Victoria University: building capacity for evidence-driven action and learning

| Building capacity for evidence-driven action and learning | Examples (related to Situation analysis and problem identification):

|

| Building capacity for evidence-driven action and learning | Examples (related to Situation analysis and problem identification):

|

Desired and unintended outcomes

Central proposition

The desired outcomes of public health research are research outcomes and population health outcomes.

Public health research can achieve both research (or academic) outcomes and population health (or societal) outcomes (see Table 1). Population health outcomes are long term goals of public health research and are theoretically presented in the Theory of Systems Change. These outcomes are expected to depend on other factors beyond the influence of research and require many years to eventuate (Halimanjaya, Belcher and Suryadarma 2018). The Theory of Systems Change also includes ‘unintended outcomes’ in recognition that, although it is often assumed that research has positive outcomes, it is essential to consider unintended and potentially harmful outcomes of research (Rau, Goggins and Fahy 2018). Consideration of unintended outcomes is particularly important in the context of systems change, where outcomes of system interactions can be unpredictable (Thompson et al. 2016; Lai and Huili Lin 2017). Working within a learning framework and being cognizant of the wider context in which research operates makes it more likely that researchers can identify, adapt, respond to, and learn from unintended outcomes as they arise.

Systems and population health outcomes

Central proposition

A target population’s health outcomes result from complex interactions between the target population and the ‘system’ or environment in which they live and grow, comprising interconnected subsystems.

Systems change approaches are grounded in the assumption that significant improvements in population health outcomes ‘will not occur unless the surrounding system adjusts to accommodate the desired goals’ of the target population, such as aligning with the needs of the target population (Foster-Fishman, Nowell and Yang 2007: 197). A ‘system’ is defined as ‘a set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its “function” or “purpose”’. (Meadows 2008: 188). In the context of the Theory of Systems Change, we elaborate on this definition to conceptualize a ‘system’ as the environment within which the target population lives and grows, comprising a range of subsystems. These subsystems include the built and natural environment (e.g. neighbourhood infrastructure) and formal (e.g. research, educational, community and governmental organizations) and informal subsystems (e.g. family, or peer influences) (Zaff et al. 2015a) that directly and/or indirectly influence the health of the target population. Based on systems theory, we acknowledge that environments are not merely thrust upon populations (in a deterministic sense), but rather form a complex web of relationships that are also influenced by the target population (Lai and Huili Lin 2017). The system selected as the focal point for a given change effort is referred to as the ‘system of relevance’ (Schutz 1953; Midgley 2006; Ulrich and Reynolds 2010).

The system of relevance for systems change efforts is determined through a process of boundary judgements and theoretical and empirical review of the key influences on the target population (e.g. youth, refugees) and problem (e.g. employment, education). In the case of place-based system change approaches, the system is bounded by well-defined geographic boundaries, such as municipalities or regions.

Research, practice, and public policy domains

Central proposition

Research, practice, and public policy domains must be considered to fully realize the potential of systems change approaches.

In public health, formal subsystems are comprised of three main domains: research, practice, and public policy (Jansen et al. 2010). We propose that all three domains must be considered to fully realize the potential of systems change approaches (Pollack Porter, Rutkow and McGinty 2018; Schäpke et al. 2018). Researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers will have different levels of power in different contexts (Best and Holmes 2010) and by bringing them together, we expect it is possible to balance and leverage power to facilitate change.

Research, practice, and public policy have different vantage points in the system and are themselves embedded in complex systems with different cultures, norms, and politics.

Although differences and boundaries exist between domains of research, practice, and public policy, a systems perspective draws attention to the three domains operating as part of a complex system, interrelating and developing, with interconnecting and overlapping boundaries (Rushmer et al. 2019). There is growing acknowledgment of the overlap and interconnection between domains (Graham et al. 2018; Nyström et al. 2018; Klepac et al. 2022), and researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers can move between domains and simultaneously occupy multiple roles. From this perspective, unifying the diverse disciplines, expertise, practices, and experiences across research, practice, and public policy domains is possible. Further, by conceptualizing research domain as part of the system, we can simultaneously explore how systems change happens and the role of research in contributing to well-functioning systems (Best and Holmes 2010; Thornton et al. 2017).

Properties of and practices within a well-functioning system

Central propositions

Well-functioning systems create conditions for improved population health outcomes for current and future generations.

The properties of, and practices within, a well-functioning system include:

engagement in evidence-driven action and learning (evidence-driven action and learning);

adaptation to external opportunities and challenges (adaptation);

alignment with the strengths and needs of the target population, across all levels of the system (alignment); and

collaboration.

Systems scholars have largely focused on defining the properties of systems as a whole, with limited conceptualization of practices within well-functioning systems (McGill et al. 2021). Defining these practices clarifies what it means for researchers, practitioners and policy-makers to be a part of a well-functioning system, allows efforts to be directed to facilitate the desired change in the system, and facilitates the measurement of well-functioning systems (Manyazewal 2017; Baugh Littlejohns and Wilson 2019).

We propose that the properties of and practices within a well-functioning system include adaptation to external opportunities and challenges; alignment with the strengths and needs of the target population (across all levels of the system); collaboration; and engagement in evidence-driven action and learning. We argue that these should be understood as both properties of the system and practices of individuals and organizations within a system. In defining the properties of and practices within a well-functioning system, we advance systems thinking literature. By focusing on the properties of and practices within well-functioning systems, we acknowledge that each system of relevance (e.g. a community) is different in the sets of conditions that give rise to the problems it faces. However, adaptation, alignment, collaboration, and evidence-driven action and learning can be applied across systems to address different problems for different target populations.

The properties of and practices within a well-functioning system that apply across research, practice, and public policy represent an in-between space where the three domains can meet, roles can be shared, discussion can take place and knowledge can be brokered and mobilized into action (Rushmer et al. 2019). As evident through the sections describing these practices below, and consistent with theory and evidence, these practices are inter-related (Selden, Sowa and Sandfort 2006; Green et al. 2016).

Evidence-driven action and learning

Evidence-driven action and learning is a continual cycle that guides decision-making and action across research, practice, and public policy. Our conceptualization of evidence-driven action and learning is based on systems thinking literature (Wadsworth 2011) and incorporates other literature concerning processes, or ‘cycles’, to support learning, improvement, and purposeful action. These cycles include the CREATE Change Cycle (Branch, Freiberg and Homel 2019), evidence-informed practice (Brownson, Fielding and Maylahn 2009), the ABLe Change Framework (Foster-Fishman and Watson 2012) and Plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycles (Taylor et al. 2014). Theory and empirical evidence highlight the importance of engaging in evidence-driven action and learning across research, practice, and public policy.

The Theory of Organizational Learning suggests that planned processes to learn from failures are important for effective organizations (Marsick and Watkins 2003). There is evidence suggesting that when collaborative entities engage in evidence-driven action and learning, they improve health related behaviours (Lin et al. 2020). Consistent with a systems perspective, our conceptualization of evidence-driven action and learning pays attention to the underlying causes that keep problems in place, the context, and the interaction between actions and changes across the system (Wadsworth 2011; Burns 2014). Cycles of evidence-driven action and learning include:

Situation analysis and problem framing: drawing on diverse sources of evidence to understand the current situation and frame a problem, paying attention both to the wider context in which the problem manifests, and how the problem affects different populations in the system (equity considerations). Framing problems in relation to their underlying causes informs the design of actions that address the underlying causes rather than the surface-level problems, leading to more effective action (Foster-Fishman and Watson 2012; Kania, Kramer and Senge 2018).

Coordinated actions: once problems/gaps/needs and underlying causes have been identified, a series of co-created, purposefully coordinated actions that target multiple levels of the system are implemented to address underlying causes (Foster-Fishman and Watson 2012; Garcia et al. 2021). These actions draw on various sources of knowledge and theory from research, practice, and public policy.

Monitoring and evaluation: includes cycles of learning whereby progress is monitored to assess if, how, and why actions achieve the desired outcome(s), paying attention to unexpected outcomes, and learning from and acting on findings. Examining how context impacts actions and outcomes is paramount to determining context’s influence and directing future actions.

Communication and dissemination: communicating and sharing knowledge and facilitating its application widely through networks and across the system (Bratianu 2015; Mayne 2020; Mckenzie 2021). Communication and dissemination of new knowledge are important across research, practice, and public policy to share lessons learned and facilitate learning networks (Burns 2007).

Adaptation

We define adaptation as the ability to respond to external changes—both opportunities and challenges (Edmondson and Moingeon 2004; Engle 2011). Adaptation to changing circumstances is central to well-functioning systems. This is consistent with the view held by systems scholars that complex systems are dynamic (Hawe, Shiell and Riley 2009) and adaptation is necessary to bring about change and maintain its impact. In the organizational literature, it is widely accepted that the ability of organizations to adapt to external pressures can explain their success or failure (Sarta, Durand and Vergne 2021), and adaptability is increasingly recognized as important to effective public health practice (van Herwerden et al. 2019).

When implementing actions, the extent to which practitioners harness the dynamic characteristics of the local context, such as resources and practices (in the process of adaptation), may predict the sustainability of their activities. As Hawe and colleagues argue, interventions in complex settings ‘…either leave a lasting footprint or wash out depending on how well the dynamic properties of the system are harnessed’ (Hawe, Shiell and Riley 2009: 270). In this way, adaptation is a two-way exchange between actions and their contexts. Systems ‘co-evolve’ and new system behaviours emerge from the adaptation process at an organizational and network level (Williams and Hummelbrunner 2010).

Alignment

We conceptualize alignment as ‘sharing the same or complementary perceived needs’ of the target population ‘and how these needs will be met’ across various system levels (e.g. practitioners, researchers, policy-makers) (Zaff et al. 2015b: 8–9). Consistent with theory and evidence (Zaff et al. 2015a,b), we propose that aligning vision, goals, and actions across the system will improve population health outcomes. Studies of effective and ineffective place-based systems change initiatives indicate that those that strive for alignment tend to be effective (Zaff et al. 2015b). Indeed, lack of alignment might explain why some initiatives have not been effective (Zaff et al., 2015b).

The importance of problem frame alignment for collaborative action that seeks to address complex problems has been noted in the literature (Bouwen and Taillieu 2004; Nowell 2010). Specifically, scholars have argued that various problem frames indicate and validate various actions, policies, and practices (e.g. Bouwen and Taillieu 2004). Therefore, a lack of alignment of problem frames—or the perception thereof—can considerably limit what can be undertaken in a collaborative setting (Nowell 2010). Consequently, the perception of a shared problem frame, or a common understanding of the nature of a problem, is integral to collective action (Bouwen and Taillieu 2004; Nowell 2010).

Collaboration

We define collaboration as any joint activity by two or more parties to link or share information, resources, activities, and capabilities to achieve aims that no single party could have achieved separately (Bryson, Crosby and Stone 2006: 44). Cross-sector collaboration is vital to place-based, systems change initiatives (Bellefontaine and Wisener 2011). It is assumed that when organizations that provide different services and programmes coordinate their efforts by working together, knowledge and expertise are shared and limited resources efficiently distributed (Provan et al. 2003). Evidence suggests that collaboration has several benefits, including improved service delivery, increased social capital, information exchange, knowledge sharing, deployment and leveraging of resources, public awareness and support, improved population outcomes, increased sustainability of evidence-based interventions, and the creation of a critical mass for action (Selden et al. 2006; Winterton et al. 2014; Green et al. 2016).

System capacity

Central propositions

A well-functioning system is predicated on the system’s capacity to engage in evidence-driven action and learning, and to adapt, align, and collaborate.

Embedding capacity in the system requires intentionally building the individual, organizational and enabling environment dimensions of capacity across research, practice and public policy domains, and strengthening relationships within and between the dimensions and domains.

The importance of ‘embedding capacity’ in a system has been noted by scholars working to create systems change (Brown et al. 2022) and it is recognized that capacity is essential for sustaining practice change over time (Hanusaik et al. 2015; United Nations Development Group 2017). Capacity must be embedded within the social structures of organizations along with the practices of individuals. It is the interaction between the two that serves to both produce and reproduce the properties of and practices within a well-functioning system (Giddens 1984).

Embedding capacity in a system requires paying attention to the dimensions of capacity and strengthening the relationship within and between the dimensions, across the domains of research, practice, and public policy (VicHealth 2012). The three dimensions of capacity include:

Individual level capacity

Individual level capacity includes confidence in engaging, skills to engage in, positive attitudes towards, and knowledge about adaptation, alignment, collaboration and evidence-driven action and learning (Hanusaik et al. 2015; United Nations Development Group 2017).

Organizational level capacity

Organizational level capacity includes organizational culture and leadership, systems and structures (e.g. IT systems, procedures, policies) that value, support, and encourage adaptation, alignment, collaboration and evidence-driven action and learning (Preskill and Torres 1999).

Enabling environment

An enabling environment influences the capacity of individuals and organizations to adapt, align, collaborate and engage in evidence-driven action and learning (adapted from World Bank 2003). One aspect of an enabling environment is public policy (e.g. legislation, funding processes). Public policy that embodies and/or values, supports and encourages adaptation, alignment, collaboration, and evidence-driven action and learning (Carey et al. 2015a; Hanusaik et al. 2015) facilitates and reinforces these practices across the system (e.g. at individual and organization level).

Relationships between and within dimensions and across practice, public policy, and research

There are reciprocal relationships across the three capacity dimensions; individuals influence organizations, and organizations support the development of individuals; public policy can support the capacity of organizations, and organizations can inform public policy (Lai and Huili Lin 2017). Further, system capacity is strengthened with relational infrastructure, or building collaboration within and between research, practice, and public policy. This reinforces the importance of collaborative vertical and horizontal networks and opportunities for engagement and networks across the system (see Burns 2007).

Research domain

Central proposition

Public health research can contribute to improvements in population health outcomes by embedding capacity to engage in evidence-driven action and learning, adapt, align, and collaborate across practice and public policy domains.

In this section, we focus on the role of the ‘research’ domain of the Theory of Systems Change, specifically how research contributes to improving population health outcomes through embedding capacity in the system (see Figure 2). We focus on the research domain as we are researchers. However, we would like to invite others, especially practitioners and policy-makers, to further contribute to the Theory of Systems Change and focus on the role of practice and public policy domains in embedding system capacity.

Embedding capacity to collaborate, adapt, align, and engage in evidence-driven action and learning is the target mechanism of change in the Theory of Systems Change. Target mechanisms of change are the outcomes that are reasonable to expect in the timeframe of a particular research project (Belcher, Suryadarma and Halimanjaya 2017). There is evidence that practitioners and policy-makers have limited capacity to adapt, align, collaborate and engage in evidence-driven action and learning (Thomas, Zimmer-Gembeck and Chaffin 2014; Hardwick, Anderson and Cooper 2015; Despard 2016; Bach-Mortensen and Montgomery 2018). Often resources, infrastructure, and leadership do not support these practices (Armstrong et al. 2014; Brownson, Fielding and Green 2018).

Pathways to embedding capacity

Central proposition

The pathways through which research can embed capacity are by involving practitioners and policy-makers in the process of knowledge production and through the communication and dissemination of research knowledge.

The capacity of practitioners and policy-makers can be developed through both involvement in the process of knowledge production (i.e. through collaboration with researchers) and the communication and dissemination of research knowledge (i.e. through evidence-driven action and learning) (Dobbins et al. 2007; Smith 2013; Kislov et al. 2014; Woolf et al. 2015; Belcher and Hughes 2020). Drawing on behaviour change literature (Michie, van Stralen and West 2011; Langer, Tripney and Gough 2016), involvement in knowledge production and communication and dissemination of research knowledge could serve one or more of the following functions to embed capacity:

Experiential learning: to increase knowledge and skills. Through collaboration, practitioners and policy-makers experience various stages of evidence-driven action and learning, which facilitates ‘hands on’ learning in problem identification, the design of coordinated actions, monitoring and evaluation, and/or communication and dissemination of knowledge (Kislov et al. 2014; Belcher and Hughes 2020).

Education: to increase knowledge, awareness, confidence, or motivation. For example, through communication and dissemination, research outputs can provide tailored and targeted information to increase their knowledge about how to align with the strengths and needs of their target population (Dobbins et al. 2007; Smith 2013; Woolf et al. 2015; Langer, Tripney and Gough 2016).

Training and technical assistance: to develop skills and knowledge. For example, short courses can develop skills for effective collaboration or ‘train-the-trainer’ programmes allow for training to be customized to local issues (Yarber et al. 2015).

Social modelling: to motivate or shift attitudes by providing an example to aspire to or imitate (Bandura 1977). For instance, when researchers model collaboration, adaptation, alignment and evidence-driven action and learning, this might motivate decision-makers to change organization procedures to support these practices.

Persuasion: to motivate or prompt attitude changes by using communication to prompt positive or negative emotions or inspire action (Pescud et al. 2022). For example, using art-based methods and imagery to evoke emotion and prompt attitude change about the importance of alignment.

Creating collaborative opportunities and/or infrastructure: to support collaboration by connecting practitioners, policy-makers and researchers and developing horizontal and vertical networks across the system (Wheatley and Frieze 2006; Langer, Tripney and Gough 2016). For example, providing platforms or infrastructure such as knowledge exchange portals to support relationship building and sharing of knowledge (Dobbins et al. 2009; Quinn et al. 2014), creating communities of practice (Barwick, Peters and Boydell 2009), or the development and funding of backbone support organizations (Kania and Kramer 2011).

Diffusion and dissemination of knowledge throughout the system: Using formal and informal collaborative networks for widespread dissemination (planned and active) and diffusion (unplanned and passive) of research knowledge (Langer, Tripney and Gough 2016). Wide networks facilitate the identification of early adopters and opinion leaders, who can amplify the dissemination and diffusion, and influence, of research knowledge (Glegg, Jenkins and Kothari 2019). Further, involvement in informal networks and collaborations provides opportunities for discussions of ideas and research.

Research knowledge attributes to enhance effectiveness and reach

Central propositions

To embed capacity within and across systems, research knowledge needs to be credible, accessible, relevant, and scalable.

When researchers engage in the practices of a well-functioning system (i.e. evidence-driven action and learning, adaptation, alignment, and collaboration), they are likely to produce research knowledge that is credible, accessible, relevant, and scalable.

Achieving system level change requires re-examining research practice, what we mean by ‘research knowledge’ and the kinds of knowledge that are useful (Best and Holmes 2010; Haynes et al. 2020). Often, research seeks standardization of practice and public policy around a proven evidence base that focuses on prescriptive knowledge or ‘evidence’ for specific programmes or policies. In contrast, the Theory of Systems Change proposes that for research to influence system level change, it must be credible, accessible, relevant, and scalable (Miller and Shinn 2005; Ashcraft, Quinn and Brownson 2020; Rushmer et al. 2019). We acknowledge that practitioners and policy-makers use various types of knowledge—including professional expertise, tacit knowledge, contextual knowledge and organizational memory when making decisions. Here, we focus on knowledge produced through research, or research knowledge (conceptualization in Table 1) (Estabrooks et al. 2006; Joseph 2013).

Accessible