-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Cian O’Donovan, Aleksandra (Ola) Michalec, Joshua R Moon, Capabilities for transdisciplinary research, Research Evaluation, Volume 31, Issue 1, January 2022, Pages 145–158, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvab038

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Problems framed as societal challenges have provided fresh impetus for transdisciplinary research. In response, funders have started programmes aimed at increasing transdisciplinary research capacity. However, current programme evaluations do not adequately measure the skills and characteristics of individuals and collectives doing this research. Addressing this gap, we propose a systematic framework for evaluating transdisciplinary research based on the Capability Approach, a set of concepts designed to assess practices, institutions, and people based on public values. The framework is operationalized through a mixed-method procedure which evaluates capabilities as they are valued and experienced by researchers themselves. The procedure is tested on a portfolio of ‘pump-priming’ research projects in the UK. We find these projects are sites of capability development in three ways: through convening cognitive capabilities required for academic practice; cultivating informal tacit capabilities; and maintaining often unacknowledged backstage capabilities over durations that extend beyond the lifetime of individual projects. Directing greater attention to these different modes of capability development in transdisciplinary research programmes may be useful formatively in identifying areas for ongoing project support, and also in steering research system capacity towards societal needs.

1. Introduction

Research framed to address global, grand, and societal challenges has brought fresh impetus to calls by funding agencies for increased transdisciplinary research capacity (Bammer et al. 2013; Lyall and Fletcher 2013; Belmont Forum 2020; European Commission 2020; Belcher and Hughes 2021). Complex and cross-domain problems such as climate change, public health programmes, and efforts to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals, provide rationales for research design that go beyond mono- or even interdisciplinary solutions (Werlen 2015). However, transdisciplinary (TD) research cannot be produced on demand. Appropriate TD research capacity is required.

We understand TD research as knowledge production activities spanning across disciplinary boundaries and meaningfully involving non-academic partners in research design, operation, analysis, publication, and the practice of attendant methods. TD research is problem-oriented, transcends separate disciplinary sectors, transgresses disciplinary and institutional boundaries and is context specific (Nowotny 2000; Klein 2006; Huutoniemi 2010). It facilitates diverse and mutually accountable interactions between participants and different styles of knowledge. In doing so, TD research potentially fosters transformative scientific and technological progress through social innovations and represented marginalized interests (Lang et al. 2012; Stirling 2015; Smith and Stirling 2018). TD research practices and evaluations are therefore ‘generative processes of harvesting, capitalizing, and leveraging multiple kinds of expertise’ (Klein 2008). While there are numerous discussions on the relations between interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity (Klein 2008; Pohl et al. 2011; Lyall Meagher Bruce 2015), they remain outside the scope of this article. Instead, we focus on the aforementioned features of transdisciplinarity as a mode of research contingent on cultivating relevant capabilities.

For expertise to be useful it must be instantiated as a kind of capability. Research capacity then is the aggregate capabilities and resources required for organizations, groups, and individuals to mobilize expertise and perform research. Building, maintaining, and evaluating TD research capacity is important in several regards. First so that a state of readiness might be reached and maintained (Klein 2008; Falk-Krzesinski et al. 2011). Readiness to do research, address wicked research problems quickly, or make complex research feasible—feasibility and risk can be an inhibiting feature of research systems (Luukkonen 2012). Second, and responding to the need for readiness, building, or enhancing capacity has become a major challenge for funders (Lyall and Meagher 2012). This has been a significant aim of major research initiatives over the past decade, including major UK projects such as RELU, UK SPINE, and UKRI CCF. Finally, capabilities and enhanced capacity are themselves a product of research, a first-order or intermediate outcome of transdisciplinary activity (Wiek et al. 2014) making TD capacity building an important impact goal of some projects (Hansson and Polk 2018).

Assessing capacity and underlying capabilities is important because they both contribute to a broader evaluation of the complex and often non-quantifiable criteria of interactions between science and society in TD research (Ernø-Kjølhede and Hansson 2011; van der Ploeg 2011). Such interactions include, but are not limited to, collaboration, integration of knowledge, learning processes, and the performance of cognitive and social functions. Moreover, evaluating TD research is important for funders normatively in measuring processes and outcomes; for demonstrating return on investment and legitimizing funding programmes (Mosse 2004). It is also analytically interesting for evaluators and researchers for what it tells us about what kind of TD research is being done and how society and research systems are reconfigured through collaborative, integrative, and ontological work (Frederiksen, Hansson and Wenneberg 2003; Molas-Gallart et al. 2016).

Methods of evaluating research programmes tend to focus on quantitative metrics of research outputs, qualitative network analysis (Oancea, Florez Petour Atkinson 2017), examining ‘productive interactions’ in research between academics and non-academics (Molas-Gallart and Tang 2011; Spaapen and van Drooge 2011), and qualitative evaluations of policy interventions (Smutylo 2001). These efforts however tend not to explicitly focus on capabilities. Nor do these efforts systematically evaluate how policy interventions build capabilities for TD research. The aim of this article is therefore to develop a framework with which to conceptualize and systematically evaluate capabilities for TD research attentive to these gaps. Our entry point is from the perspective of UK research funding agencies, and their institutional obligation to expand capacity on the academic side of transdisciplinary collaborations. As such, our evaluation centres on the capabilities of academic researchers in the first instance.

We discuss the particulars of these capabilities and how they might arise in Section 2, where we also provide an account of the evaluative framework’s conceptual underpinnings using the Capabilities Approach (Sen 1999; Nussbaum 2001). In order to locate, explore and assess the presence of research capabilities in the field, we propose a novel framework of evaluation. Our research question is: what are the different capabilities valued by researchers performing TD research, and how can these be mapped in specific research projects?

We describe the procedural tasks of evaluation and propose a novel methodological approach in Section 3. In Section 4, we demonstrate the framework with a case study of a TD research programme, the ESRC Nexus Network+ (NN+)1. We discuss the analysis and implications for evaluation practice, theory, and policy in Section 5. Section 6 offers a short conclusion.

2. Theory: evaluating capabilities for transdisciplinary research

2.1. Locating transdisciplinary research capabilities in practice and theory

What can we learn from how evaluators have conceptualized capabilities to date? Here we understand capabilities as an individual or group’s ability to do valuable acts or reach valuable states of being in pursuit of TD research. For instance, skills, aptitudes (Lyall and Meagher 2012), competences (Hoffmann et al. 2017; Hansson and Polk 2018), and human capital (Bozeman et al. 2001) are all relevant to human capabilities and feature in procedures evaluating the impacts and outputs of research. Our primary interest in outputs is in how they contribute to research capacity and readiness levels and the capabilities that are variously constitutive of these outputs or required in their production. In this way, scientific and technological human capital (Bozeman et al. 2001; Bozeman and Corley 2004) can be understood as outputs and inputs of TD research. These include skills and career prospects of expert researchers measured using bibliometric techniques and content analysis of CVs. Similar techniques have been used to assess capabilities produced in graduate courses and on research teams (de Oliveira et al. 2019).

Capabilities also feature in evaluations of research processes. Processes and constituent research practices include the cognitive disciplinary work of research as well as the integrative (Boix-Mansilla 2006) and ontological (Barry, Born and Weszkalnys 2008) work of TD research. They also include social and collaborative practices across project groups and with stakeholders in society. These processes are underpinned in part by what Klein (2008) calls ‘competencies’. That is, how well methods for decision-making, knowledge distribution, and networking are managed across projects and sub-projects. These methods in turn require management, coaching, and leadership capabilities.

Cutting across evaluations of outputs and processes are issues of quality (Feller 2006; Huutoniemi et al. 2010; de Jong et al. 2011; Belcher et al. 2016). Collaboration for example, can be evaluated as a process, and also be used as an indicator of research quality (de Jong et al. 2011). Collaborative practices in particular draw our attention to capabilities that are inherently collective, that is situated across groups. TD quality can be enhanced through the enacting of certain capabilities: mastering multiple disciplines, emphasizing integration, critiquing disciplinarity (Huutoniemi 2010). Effectiveness is one useful criterion of quality with which evaluators can assess social learning (the change in knowledge, attitudes, and skills at the individual, group, and institutional level) and the building of what they call societal capacity (Belcher et al. 2016).

A common feature of TD research is that assessments of quality are relative to the goals, expectations, norms, and values of research stakeholders and thus vary from one TD research context to another (Huutoniemi 2010). De Jong (2011) for example evaluates performance of a research groups against their own research aims. More broadly, the role of context in TD research has formed an important theme within evaluation literature (Feller 2006; Stokols et al. 2008; Hansson and Polk 2018). Evaluators that assess context draw attention to the role of norms, institutions, rules, and conditions of enquiry in shaping, enhancing, and diminishing individual and group capabilities (Mormina 2019). Context is also the location for interventions that might enhance capabilities and capacity for integration and collaboration (Klein 2008).

This brief discussion indicates some of the features a framework to evaluate capabilities needs to incorporate. It needs to understand capabilities as constitutive of research practice, as well as outputs of research processes. It needs to account for social as well as cognitive capabilities and those performed by individuals as well as groups. It needs to be sensitive to the effect of contextual features on research practice and the complexity of situations in which they arise. It needs to take into account the aims of specific research projects and constituent researchers. And it needs to acknowledge the subjectivity and politics inherent in the values and decisions that determine which knowledge and methods are made to matter through processes of reflection, deliberation, and negotiation (Wiek et al. 2014) or otherwise. To accomplish this, we conceptualize capabilities using the Capability Approach and operationalize the framework using a realist evaluation technique (Section 3).

2.2. The capability approach—evaluating what researchers are effectively able to do

What are capabilities exactly, and what capabilities are required to carry out these TD research practices? Moreover, what can an assessment of capabilities tell us that current evaluative procedures cannot? Concepts about human capabilities by development scholars such as Amartya Sen (1999) and Martha Nussbaum (2001) are useful here. The Capability Approach (CA) is a framework with which to assess institutions and practices based on one or several public values, conceptualized in capability terms (Robeyns 2016). Emerging from assessments of public values related to quality of life (Sen) and social justice (Nussbaum), the CA has been used for a range of theoretical and conceptual work (Robeyns 2016). These include small-scale project evaluation (Alkire 2005) and assessing human capabilities in collaborative workshops (O’Donovan and Smith 2020). Much research has been published on education and capabilities (Saito 2003; Walker 2003) but rather less on the practices of research. Addressing this gap, we develop a conceptualization of capabilities for TD research that are valued by researchers and other interested agents.

The core characteristic of the approach is its focus on what people are effectively able to do and be; that is, on their capabilities (Robeyns 2005 p. 94). For example, the research techniques available for researchers to choose to practice—such as the capability to do ethnographic fieldwork, or to be an environmental economist. In other words, something discrete and measurable, so a research project’s capability set can be thought of like a budget set—the capabilities valued and available to that project. The CA is normative in that it supports analysis and decisions based on value judgements about how research groups ought to behave in order to create research with and for society. A major strength of the CA is that it allows us account for the normative assumptions of the research subjects, in our case TD researchers.

To be clear, in our evaluation we focus on the cultivation and availability of capabilities to act, rather than the achievements of the group being evaluated—what capability theorists call achieved functionings. Robeyns (2005) provides a comprehensive overview of concepts and procedures used in theorizing and operationalizing capability frameworks, of which the most relevant to the aims of this article are sketched out below. 2

2.3. Our conceptual framework

We now introduce a conceptual framework that builds on the evaluative features of the capability approach in order to address the issues of TD research discussed in Section 2.1. TD research projects form the evaluative space—what we will refer to as a capability space—for our framework. But what capabilities matter within these projects?

Our analysis follows Sen (1999) and Robeyns (2005) in seeing the capabilities valued by and available to researchers as a matter of empirical identification. Moreover, taking the situatedness of TD research seriously directs us to paying attention to how researcher might value specific capabilities differently depending on the context of the research. After all, TD research gains in accountability precisely because of the situated nature of the socially robust knowledge it might generate.

Nevertheless, we do not start from an entirely blank slate. The literature discussed in Section 2.1 gives us some clues as to what kind of capabilities are likely to be valued by researchers in TD research projects generally. We use this literature as a starting point with which to map the capability spaces of the NN+ projects specifically.

To guide our exploration of these spaces we propose a four-part, conceptually driven heuristic. These parts account for (i) individual capabilities held by researchers; (ii) collective capabilities held within the capability set of the research projects; (iii) cognitive capabilities required to perform academic practices and again collectively held in the context of transdisciplinary research; (iv) contextual features which shape the capability space of research projects. The idea is to use this heuristic to direct our attention to where and how capabilities are most likely to be situated, whilst—again following Robeyns (2005)—inductively locating them through bibliometric techniques, grounded methods, and careful analysis.

2.3.1 Individual capabilities

Many capabilities required for research are more ‘social or political than simply cognitive’ (Bozeman and Rogers 2001, p. 418). These include ‘the strategies and policies of knowing that are not codified in textbooks but nevertheless inform expert practice’ (Knorr Cetina 1999, p. 2). Examples include skills, tacit knowledge, and experiential knowledge acquired by individual researchers (Heckman and Corbin 2016) and performed in the social setting of research projects. Tacit, social, and cognitive factors interact, requiring management of information and decision-making (Klein 2006). Such tacit individual capabilities are influenced by personal background and include often individualistic ambitions like the capability to have an identity as a researchers (Lau and Pasquini 2008).

2.3.2 Collective capabilities

Bozeman and Rogers considered the human and technical capital required for research to include the ‘sum total of scientific, technical, and social knowledge and skills and capabilities available to a particular individual’ (Bozeman and Rogers 2001). In TD practice though, individual researchers rarely, if ever, cultivate all of these capabilities required to carry out research. Research project groups facilitate the division of labour, share expertise, and contribute mutual or collective capabilities and are an everyday feature of scientific research.

CA scholars have shown how the provision and achievement of capabilities is held, used and influenced by group, social, and environmental factors (Stewart 2005; Ibrahim 2006). Moreover, a set of capabilities available to an individual or group can be expanded through collective action as well as individual effort (Stewart 2005; Roy 2012). Two points are important here. First, we can expect that a research group’s capability set contains the aggregate of individual capabilities. Second, the capability set also contains capabilities that are mutually held and not dividable to individual researchers. In other words, there are collective capabilities of a group that are not features of individuals on their own.

For example, the production of scientific knowledge, legitimacy and individual expertise is influenced socially (Cuevas Garcia 2016) and culturally (Corley et al. 2019). Collective capabilities that might be valued by researchers include capabilities for collaboration and coordination (Hohl, Knerr and Thompson 2019), capabilities to build and continuously maintain networks (Spaapen and van Drooge 2011; Hansson and Polk 2018) and to promote interpersonal and intrapersonal learning that can foster enhanced understanding and capabilities to respond to complex questions, issues, or problems (Lyall and Meagher 2012).

2.3.3 Cognitive capabilities

Indeed, the expansion of collective cognitive capabilities is an evaluative impact of research in itself (Molas-Gallart, Tang and Rafols 2014). These are the capabilities required to perform scientific and technical work include formal educational endowments acquired through graduate and post-graduate training, usually encompassed in concepts of ‘human capital’ (e.g. Becker 1964). These cognitive capabilities variously include the skills and formally taught techniques required, for instance, to take soil samples, conduct interviews, or perform econometric modelling and to perform advanced knowledge tasks such as differentiating, reconciling and synthesizing (Lyall and Meagher 2012).

The provision of these capabilities usually follows disciplinary lines in undergraduate education and often through post-graduate training. These demarcations are also evident in academic journals, which remain, for the most part, closely organized along disciplinary lines (Rafols et al. 2012). Critically for this study, the capability to publish in a disciplinary journal is an important indicator of the capabilities available collectively to researchers in the context of the specific research projects we investigate.

2.3.4 Contextual influences on capabilities

The social and material contexts in which capabilities are put into practice in the production of knowledge are multiple, patchy and heterogeneous (Pickering 1992, p. 8). These include offices in academic departments, disciplinary norms, methods, campus rules, research ethics frameworks, field locations and the myriad of instruments, tools, knowledges, and relations at and between these sites (Feller 2006; Hansson and Polk 2018). In evaluation, flexibility and sensitivity to this diversity and context is critical (Langfeldt 2006).

The normative evaluation of capabilities in context was part of Sen’s motivation in early developments of the CA (Couldry 2019). This milieu of social institutions, norms, environmental factors, guiding policy visions, regulations, and people’s behaviours are what CA analysts call conversion factors that mediate capability inputs, such as knowledge, finance, resources, goods, and services that in turn facilitate the cultivation of capabilities within a capability set (Robeyns 2005). The degree, distribution, and quality of capabilities within a research project is shaped by these factors. Exactly how is, again, a matter for empirical research. Our framework is attentive on the one hand to how researchers might value capabilities differently depending on the context of specific projects. And on the other, to how contextual phenomena influence the availability of capabilities valued by researchers within a capability space. To be clear, the contextual influences that form the final part of our heuristic are not strictly capabilities, but rather the broader social contexts and socio-material configurations of research projects that influence capabilities (Robeyns 2005; Oosterlaken 2011; Zheng and Stahl 2011). Heuristic components are summarised in Table 1.

3. Methods

Based on our conceptualization of transdisciplinary research projects, we need a methodology that accomplishes a series of analytic tasks.

Stage I: identify inductively a list of capabilities associated with TD research practices.

Stage II: appraise how the capabilities claimed for TD research sites are actually experienced by researchers.

Stage III: compare the capabilities in Stage I with those mapped in Stage II in order to identify expected and absent capabilities.

To achieve this, we follow a typical evaluation pathway (Gilmore et al. 2019): establishing expectations, determining reality, and locating differences—in this case between expected capabilities and those which are experienced by researchers. This is a theory-driven approach that lets us locate discrete sets of capabilities, while also acknowledging the limitations, situatedness, and contextual features of those capabilities.

3.1 Realist evaluation and the capabilities approach

The three tasks outlined above are typical of a Realist Evaluation (RE) in which the core expectations of an Initial Programme Theory (IPT) are set a priori (Stage I) (Nurjono et al. 2018). Data appropriate to examining that IPT is then collected (Stage II). Then IPT expectations are recursively compared with reality (Stage III). Importantly for our purposes, while alternative forms of theory-driven evaluation (for instance programme-theory evaluation or theory-of-change evaluation) ask questions about ‘what works?’, RE is focused on ‘what works for whom and in what contexts?’ (Pawson and Tilley 1997). As such, RE enables us to not only discover what capabilities enabled researchers to conduct TD research, but how the situatedness of those capabilities shaped their usefulness. We detail the methodology for each of these stages in turn.

3.2.1 Stage I—compiling a list of expected capabilities

Adapting the CA for analytical purposes requires careful explanation and justification of the relevant capabilities identified and the methods used. Robeyns (2003) sets out identification criteria: they should be explicit, discussed and defended. The level of abstraction should be appropriate to the study context and project objectives. Ideal sets of capabilities must become a pragmatic list that can be studied and should include all important elements non-reducible to the other elements, even if there exists some overlap.

Guided by these criteria we identified a list of capabilities expected in the test programme, arrived at by searching for signals of our conceptual framework in a focused review of the literature on conducting and evaluating TD research. We began the task by searching the literature for signals and expressions of our conceptual framework—cognitive, tacit, collective beings, and doings. We refined this list using project documentation (project proposals, annual reports, etc.) from within the NN+ partnership programme. Finally, we integrated observations from two workshops organized by the NN+, ‘Transdisciplinary Methods for Developing Nexus Capabilities’. Details of these sources of evidence are reported in Section 4.1 (Table 2) and identified capabilities are reported in Section 4.3.

Characteristics of Nexus Network Partnership Programme, projects, and workshops. These characteristics are augmented by further bibliometric data and analysis in the Supplementary material

| Item . | Background . |

|---|---|

| Partnership programme overview | In 2016, NN+ launched their Partnership Programme, awarding five projects between £60,000 and £120,000 each. The aim: building capabilities that supported ‘the development and implementation of transdisciplinary research on nexus-related topics’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). Transdisciplinary approaches were mandated through two assessment criteria. First scope: ‘does the application engage with two or more nexus areas (food, energy, water, and environment)’ and second engagement strategy: ‘does the application outline a persuasive strategy for engagement between disciplines and between researchers and other knowledge partners? …do the applicants display a depth of understanding about the possible barriers and challenges to inter- and trans-disciplinary work’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). |

| Project 1 | This project aimed to engage policy makers with the social sciences’ theories (human geographers, sociologists, and environmental studies scholars) on sustainable kitchen practices. In this project we note diversity of cognitive capabilities is underpinned with evidence of strong cognitive links between researchers. The project has been led by a well-connected and involved senior social scientist. This has been built up over a long timeframe: researchers were located in one of the UK regions and policy collaborators worked closely with the central government. |

| Project 2 | The project combined UK-based economic and soil science analysis to aid farmers’ decision-making in an overseas location. In this project the primary investigator (economist) enacts a strong individual leadership role in aligning people and their capabilities. This was reinforced by concurrent activities mobilized by another non-NN+ project run over a similar timeframe. Nevertheless, larger ambitions had to scale down due to delays caused by the complexity of administrating research activities overseas. |

| Project 3 | The project aimed to collect a diverse array of natural science data from an overseas region and integrate them into the already existing social science database of the area. The project engaged with the local policy makers and community members during data collection and outreach. The primary investigator (anthropologist) played a convening role and was not involved day to day. The UK-based research group (also a team of anthropologists) had already funded a PhD researcher at an overseas partner research organization indicative of, and constitutive of a long-established trans-national research network. Difficult to ascertain where the power lay between partners. |

| Project 4 | This project gathered qualitative insights on energy production, consumption and related sustainability dilemmas in an overseas location. The research was conducted by scholars working across Science and Technology Studies (PI and researchers) and Engineering (Co-Is). In this project, cognitive capabilities related to interpretive research techniques existed within the UK academic team but were not uniformly matched in the field. The funding itself did not allow for training. Capabilities did not exist to easily connect UK and overseas academic structures creating delays and other barriers to getting work done. |

| Project 5 | The project developed a series of deliberations on the future scenarios related to sustainable food systems in one of the UK countries. In this project the primary investigator (sociologist) played a convening role initially and was not involved in day-to-day activities of the project. The main researcher (with background in environmental policy) did not have pre-existing connections with the practitioners participating the in the project. The short-term nature of the NN+ funding did not allow to create a community of practice which would last beyond the timescales of data collection and dissemination. |

| Workshop 1 | The Transdisciplinary Methods for Developing Nexus Capabilities workshop brought together researchers from across the broader Nexus Network as well as others with an interest or expertise in TD research for sustainability (Ince 2015). Workshop activities were framed by a discussion paper (Stirling 2015) and yielded observations about capabilities which for participants were important in addressing the needs of TD research. |

| The workshop was organized around two questions: (1) What different kinds and interconnections of method in contrasting contexts, form the most practical basis for enabling transformative action to address Nexus challenges? (2) How can such encompassing Nexus methodologies best enable academic, government, business, and civil society actors to develop appropriate skills, training, and research capabilities? | |

| Workshop 2 | A workshop in May 2018 convened researchers from across the NN+ Partnership Programme. Participants were invited to reflect on capabilities within their projects by building their own maps of stakeholders, project participants, socio-material relations, resources, and institutions (Schiffer 2007). This method was adept at capturing collective capabilities and structural and contextual conditions. Participants were also asked to respond to representations of bibliometric profiles constructed of each research team, augmenting bibliometric-based cognitive indicators with qualitative observations and drawing attention to absences in those data (Ayre and O’Donovan 2018). |

| Item . | Background . |

|---|---|

| Partnership programme overview | In 2016, NN+ launched their Partnership Programme, awarding five projects between £60,000 and £120,000 each. The aim: building capabilities that supported ‘the development and implementation of transdisciplinary research on nexus-related topics’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). Transdisciplinary approaches were mandated through two assessment criteria. First scope: ‘does the application engage with two or more nexus areas (food, energy, water, and environment)’ and second engagement strategy: ‘does the application outline a persuasive strategy for engagement between disciplines and between researchers and other knowledge partners? …do the applicants display a depth of understanding about the possible barriers and challenges to inter- and trans-disciplinary work’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). |

| Project 1 | This project aimed to engage policy makers with the social sciences’ theories (human geographers, sociologists, and environmental studies scholars) on sustainable kitchen practices. In this project we note diversity of cognitive capabilities is underpinned with evidence of strong cognitive links between researchers. The project has been led by a well-connected and involved senior social scientist. This has been built up over a long timeframe: researchers were located in one of the UK regions and policy collaborators worked closely with the central government. |

| Project 2 | The project combined UK-based economic and soil science analysis to aid farmers’ decision-making in an overseas location. In this project the primary investigator (economist) enacts a strong individual leadership role in aligning people and their capabilities. This was reinforced by concurrent activities mobilized by another non-NN+ project run over a similar timeframe. Nevertheless, larger ambitions had to scale down due to delays caused by the complexity of administrating research activities overseas. |

| Project 3 | The project aimed to collect a diverse array of natural science data from an overseas region and integrate them into the already existing social science database of the area. The project engaged with the local policy makers and community members during data collection and outreach. The primary investigator (anthropologist) played a convening role and was not involved day to day. The UK-based research group (also a team of anthropologists) had already funded a PhD researcher at an overseas partner research organization indicative of, and constitutive of a long-established trans-national research network. Difficult to ascertain where the power lay between partners. |

| Project 4 | This project gathered qualitative insights on energy production, consumption and related sustainability dilemmas in an overseas location. The research was conducted by scholars working across Science and Technology Studies (PI and researchers) and Engineering (Co-Is). In this project, cognitive capabilities related to interpretive research techniques existed within the UK academic team but were not uniformly matched in the field. The funding itself did not allow for training. Capabilities did not exist to easily connect UK and overseas academic structures creating delays and other barriers to getting work done. |

| Project 5 | The project developed a series of deliberations on the future scenarios related to sustainable food systems in one of the UK countries. In this project the primary investigator (sociologist) played a convening role initially and was not involved in day-to-day activities of the project. The main researcher (with background in environmental policy) did not have pre-existing connections with the practitioners participating the in the project. The short-term nature of the NN+ funding did not allow to create a community of practice which would last beyond the timescales of data collection and dissemination. |

| Workshop 1 | The Transdisciplinary Methods for Developing Nexus Capabilities workshop brought together researchers from across the broader Nexus Network as well as others with an interest or expertise in TD research for sustainability (Ince 2015). Workshop activities were framed by a discussion paper (Stirling 2015) and yielded observations about capabilities which for participants were important in addressing the needs of TD research. |

| The workshop was organized around two questions: (1) What different kinds and interconnections of method in contrasting contexts, form the most practical basis for enabling transformative action to address Nexus challenges? (2) How can such encompassing Nexus methodologies best enable academic, government, business, and civil society actors to develop appropriate skills, training, and research capabilities? | |

| Workshop 2 | A workshop in May 2018 convened researchers from across the NN+ Partnership Programme. Participants were invited to reflect on capabilities within their projects by building their own maps of stakeholders, project participants, socio-material relations, resources, and institutions (Schiffer 2007). This method was adept at capturing collective capabilities and structural and contextual conditions. Participants were also asked to respond to representations of bibliometric profiles constructed of each research team, augmenting bibliometric-based cognitive indicators with qualitative observations and drawing attention to absences in those data (Ayre and O’Donovan 2018). |

Characteristics of Nexus Network Partnership Programme, projects, and workshops. These characteristics are augmented by further bibliometric data and analysis in the Supplementary material

| Item . | Background . |

|---|---|

| Partnership programme overview | In 2016, NN+ launched their Partnership Programme, awarding five projects between £60,000 and £120,000 each. The aim: building capabilities that supported ‘the development and implementation of transdisciplinary research on nexus-related topics’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). Transdisciplinary approaches were mandated through two assessment criteria. First scope: ‘does the application engage with two or more nexus areas (food, energy, water, and environment)’ and second engagement strategy: ‘does the application outline a persuasive strategy for engagement between disciplines and between researchers and other knowledge partners? …do the applicants display a depth of understanding about the possible barriers and challenges to inter- and trans-disciplinary work’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). |

| Project 1 | This project aimed to engage policy makers with the social sciences’ theories (human geographers, sociologists, and environmental studies scholars) on sustainable kitchen practices. In this project we note diversity of cognitive capabilities is underpinned with evidence of strong cognitive links between researchers. The project has been led by a well-connected and involved senior social scientist. This has been built up over a long timeframe: researchers were located in one of the UK regions and policy collaborators worked closely with the central government. |

| Project 2 | The project combined UK-based economic and soil science analysis to aid farmers’ decision-making in an overseas location. In this project the primary investigator (economist) enacts a strong individual leadership role in aligning people and their capabilities. This was reinforced by concurrent activities mobilized by another non-NN+ project run over a similar timeframe. Nevertheless, larger ambitions had to scale down due to delays caused by the complexity of administrating research activities overseas. |

| Project 3 | The project aimed to collect a diverse array of natural science data from an overseas region and integrate them into the already existing social science database of the area. The project engaged with the local policy makers and community members during data collection and outreach. The primary investigator (anthropologist) played a convening role and was not involved day to day. The UK-based research group (also a team of anthropologists) had already funded a PhD researcher at an overseas partner research organization indicative of, and constitutive of a long-established trans-national research network. Difficult to ascertain where the power lay between partners. |

| Project 4 | This project gathered qualitative insights on energy production, consumption and related sustainability dilemmas in an overseas location. The research was conducted by scholars working across Science and Technology Studies (PI and researchers) and Engineering (Co-Is). In this project, cognitive capabilities related to interpretive research techniques existed within the UK academic team but were not uniformly matched in the field. The funding itself did not allow for training. Capabilities did not exist to easily connect UK and overseas academic structures creating delays and other barriers to getting work done. |

| Project 5 | The project developed a series of deliberations on the future scenarios related to sustainable food systems in one of the UK countries. In this project the primary investigator (sociologist) played a convening role initially and was not involved in day-to-day activities of the project. The main researcher (with background in environmental policy) did not have pre-existing connections with the practitioners participating the in the project. The short-term nature of the NN+ funding did not allow to create a community of practice which would last beyond the timescales of data collection and dissemination. |

| Workshop 1 | The Transdisciplinary Methods for Developing Nexus Capabilities workshop brought together researchers from across the broader Nexus Network as well as others with an interest or expertise in TD research for sustainability (Ince 2015). Workshop activities were framed by a discussion paper (Stirling 2015) and yielded observations about capabilities which for participants were important in addressing the needs of TD research. |

| The workshop was organized around two questions: (1) What different kinds and interconnections of method in contrasting contexts, form the most practical basis for enabling transformative action to address Nexus challenges? (2) How can such encompassing Nexus methodologies best enable academic, government, business, and civil society actors to develop appropriate skills, training, and research capabilities? | |

| Workshop 2 | A workshop in May 2018 convened researchers from across the NN+ Partnership Programme. Participants were invited to reflect on capabilities within their projects by building their own maps of stakeholders, project participants, socio-material relations, resources, and institutions (Schiffer 2007). This method was adept at capturing collective capabilities and structural and contextual conditions. Participants were also asked to respond to representations of bibliometric profiles constructed of each research team, augmenting bibliometric-based cognitive indicators with qualitative observations and drawing attention to absences in those data (Ayre and O’Donovan 2018). |

| Item . | Background . |

|---|---|

| Partnership programme overview | In 2016, NN+ launched their Partnership Programme, awarding five projects between £60,000 and £120,000 each. The aim: building capabilities that supported ‘the development and implementation of transdisciplinary research on nexus-related topics’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). Transdisciplinary approaches were mandated through two assessment criteria. First scope: ‘does the application engage with two or more nexus areas (food, energy, water, and environment)’ and second engagement strategy: ‘does the application outline a persuasive strategy for engagement between disciplines and between researchers and other knowledge partners? …do the applicants display a depth of understanding about the possible barriers and challenges to inter- and trans-disciplinary work’ (The ESRC Nexus Network 2016). |

| Project 1 | This project aimed to engage policy makers with the social sciences’ theories (human geographers, sociologists, and environmental studies scholars) on sustainable kitchen practices. In this project we note diversity of cognitive capabilities is underpinned with evidence of strong cognitive links between researchers. The project has been led by a well-connected and involved senior social scientist. This has been built up over a long timeframe: researchers were located in one of the UK regions and policy collaborators worked closely with the central government. |

| Project 2 | The project combined UK-based economic and soil science analysis to aid farmers’ decision-making in an overseas location. In this project the primary investigator (economist) enacts a strong individual leadership role in aligning people and their capabilities. This was reinforced by concurrent activities mobilized by another non-NN+ project run over a similar timeframe. Nevertheless, larger ambitions had to scale down due to delays caused by the complexity of administrating research activities overseas. |

| Project 3 | The project aimed to collect a diverse array of natural science data from an overseas region and integrate them into the already existing social science database of the area. The project engaged with the local policy makers and community members during data collection and outreach. The primary investigator (anthropologist) played a convening role and was not involved day to day. The UK-based research group (also a team of anthropologists) had already funded a PhD researcher at an overseas partner research organization indicative of, and constitutive of a long-established trans-national research network. Difficult to ascertain where the power lay between partners. |

| Project 4 | This project gathered qualitative insights on energy production, consumption and related sustainability dilemmas in an overseas location. The research was conducted by scholars working across Science and Technology Studies (PI and researchers) and Engineering (Co-Is). In this project, cognitive capabilities related to interpretive research techniques existed within the UK academic team but were not uniformly matched in the field. The funding itself did not allow for training. Capabilities did not exist to easily connect UK and overseas academic structures creating delays and other barriers to getting work done. |

| Project 5 | The project developed a series of deliberations on the future scenarios related to sustainable food systems in one of the UK countries. In this project the primary investigator (sociologist) played a convening role initially and was not involved in day-to-day activities of the project. The main researcher (with background in environmental policy) did not have pre-existing connections with the practitioners participating the in the project. The short-term nature of the NN+ funding did not allow to create a community of practice which would last beyond the timescales of data collection and dissemination. |

| Workshop 1 | The Transdisciplinary Methods for Developing Nexus Capabilities workshop brought together researchers from across the broader Nexus Network as well as others with an interest or expertise in TD research for sustainability (Ince 2015). Workshop activities were framed by a discussion paper (Stirling 2015) and yielded observations about capabilities which for participants were important in addressing the needs of TD research. |

| The workshop was organized around two questions: (1) What different kinds and interconnections of method in contrasting contexts, form the most practical basis for enabling transformative action to address Nexus challenges? (2) How can such encompassing Nexus methodologies best enable academic, government, business, and civil society actors to develop appropriate skills, training, and research capabilities? | |

| Workshop 2 | A workshop in May 2018 convened researchers from across the NN+ Partnership Programme. Participants were invited to reflect on capabilities within their projects by building their own maps of stakeholders, project participants, socio-material relations, resources, and institutions (Schiffer 2007). This method was adept at capturing collective capabilities and structural and contextual conditions. Participants were also asked to respond to representations of bibliometric profiles constructed of each research team, augmenting bibliometric-based cognitive indicators with qualitative observations and drawing attention to absences in those data (Ayre and O’Donovan 2018). |

3.2.2 Stage II—mapping capabilities at research sites

Following Step 2 in the realist evaluation procedure and further guided by the heuristic, we next gathered data on actual capabilities valued by researchers within each case. In order to map the collective cognitive capabilities available at each research project, bibliometric profiles for the respective projects were compiled. These consisted of aggregate records of peer-reviewed journal publications of constituent researchers, collected on 20th August 2018 (no time boundary). Mapping the bibliometric profiles onto Web of Science categories (Leydesdorff, Carley and Rafols 2013) gave us indicators of different cognitive capabilities and disciplines that constituted each of the NN+ projects. 3 Furthermore, and despite some limitations, for each of these project profiles, a co-authorship map gave us inference into potential relations between project researchers.

Knowledge outputs such as bibliometric indicators, however, only partially reveal characteristics of a knowledge community (Strathern 2004) and are insufficient to capture the nature of transdisciplinary programmes (Koier and Horlings 2015); for instance reduced efficacy for early career researchers and non-academic participants (who have fewer publications). These limitations were mitigated through close analysis of the project proposals and the self-reported biographies of project researchers. Also, findings derived from bibliometric analysis were explicitly triangulated and augmented, first at workshop 2 (see Table 2) and over the course of researcher interviews.

In parallel, a questionnaire was deployed to all researchers in the five NN+ projects and this article reports 26 respondents. The questionnaire asked about the nature and frequency of interpersonal interactions within and across projects in order to map further individual, collective and group capabilities. It also sought to generate data on how capabilities were valued and experienced by researchers. This added qualitative data from individuals who were not available for interview, triangulating project narratives. Moreover, this provided an insight into the collective and contextual capabilities in the projects (Ayre and O’Donovan 2018). Data from the questionnaire and bibliometric analyses formed the basis for 15 semi-structured interviews with project researchers from across the five NN+ projects. PIs, Co-Is, and research associates as well as and practitioner partners were interviewed. These interviews provided further feedback loops within the evaluation framework. They also allowed identification of research practices and capability experiences that were important to researchers actually doing the research.

3.2.3 Stage III—comparing the list of expected capabilities with evidence from research projects

The final step of realist evaluation is in practice multiple iterations of the same step—to iteratively reflect upon our initial list of capabilities as our data collection and analysis evolves (Gilmore et al. 2019). Stage III occurred in parallel with Stages I and II. This interplay between expectations and reported reality is where realist evaluation highlights those aspects which are structural, unexpected, or absent entirely. As more data was gathered, project stories became thicker, more detailed, and increased in specificity. This allowed us to infer more accurately the capabilities valued by researchers within each project and therefore refine our Initial Programme Theory (the capabilities list).

4. Evaluating transdisciplinary capabilities in the nexus network+

4.1 The nexus network+ partnership programme

In 2014, the ESRC Nexus Network+ was awarded £1.5 m in funding by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council in order to build a network of researchers capable of examining interactions within and between domains of water, energy, and food, the WEF nexus (Cairns, Wilsdon and O’Donovan 2017; UKRI 2020). The Network + was the second iteration of a new ‘pump-priming’ model introduced by UK public funding agencies which included the provision of refunding budget for onward distribution over the course of several programmes of activities. Characteristics of the programme and projects are introduced in Table 2, and further bibliometric data are available in the Supplementary material. In the following sections, we report on capabilities valued by researchers across the entire portfolio. We begin by demonstrating the framework in action by reporting in-detail on Project 1.

4.2 Mapping the capabilities within NN+ partnership programme Project 1

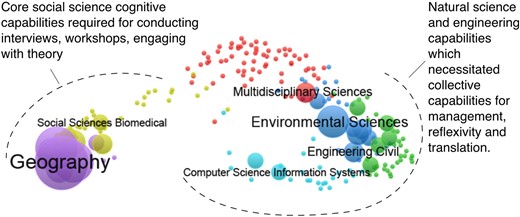

The aim of Project 1 was to facilitate the transfer of research findings from environmental social sciences into the UK policy context (Table 2). Bibliometric analysis indicates disciplinary characteristics of the set of collective cognitive capabilities such as capabilities in geography and other social sciences with environmental sciences and civil engineering (Figure 1).

Collective cognitive capabilities available in Project 1, mapped onto a Map of Science overlay map (Leydesdorff et al. 2013). Each node represents a Web of Science category (cognate discipline), in sum indicating the collective cognitive capabilities available at the project. Clusters of cognate disciplines are based on citation flows in the overall WoS corpus and are represented by nodes sharing the same colour—available in online edition. The two dominant clusters in the figure indicate the research team is constitutive of capabilities from geography and social sciences (left cluster) and environmental sciences and civil engineering (right).

Figure 1 reveals the presence of social science capabilities on the left-hand side in line with the ESRC’s goal for the NN+ to ‘engage the social science community with these complex ‘Nexus challenges’ and link them to research users from business, government, and civil society’ (UKRI 2020). This already indicates the possibility of an incursion of social science methods and capabilities into the WEF nexus idiom, traditionally composed of engineering and environmental science expertise, for instance capabilities for optimizing, modelling, and quantifying.

The large clusters on the right-hand side indicate researchers with published outputs in the natural and environmental sciences and engineering indicating a plurality of cognitive capabilities available collectively at the project. Nevertheless, interpretive social scientists with a shared interest in the domestic use of water, energy and food were in the majority. For these researchers, collaboration with practitioners was more significant than the integration of knowledge across academic disciplines:

‘Insofar as our project was transdisciplinary, it was transdisciplinary in terms of involving practitioners as well as academics. Personally, the term I would use would probably be ‘collaborative research’ because it was collaborating with practitioners’ (Project 1 researcher).

Another explanation for why integration is underplayed is that researchers did not collect novel environmental science and engineering data—their analytic focus was elsewhere.

Qualitative data also revealed the presence of other collective capabilities in the project. For instance, capabilities to translate, integrate, and operationalize diverse methods. These are collective because they involve researchers from different disciplines collaborating. These also included capabilities to allow researchers collectively reflect on previous collaborations which were required to effectively translate social science perspectives to practitioner partners in water, energy, and food industries.

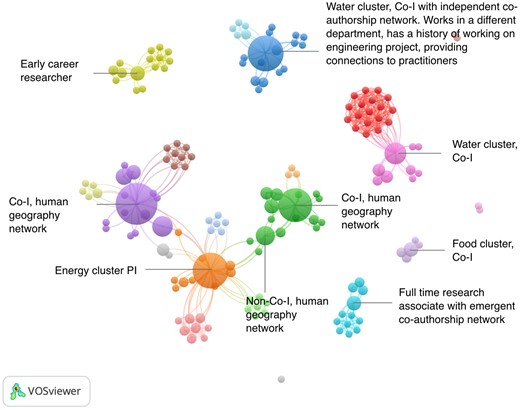

Augmenting the project’s co-authorship network with practitioner relations found in the data, we found that the project’s capability set was influenced by three distinct networks (shown in Figure 2). First, the network illustrates what one interviewee—referring to the region in which their colleagues worked—called a ‘disciplinary North-West hub’ of predominantly social theorists, whose expertise is located in various domains of the water-energy-food nexus. Second, a social science—engineering network is evidenced, revealing working relations established over a decade. One co-investigator (the relatively isolated ‘water cluster Co-I’ at the top of the graph) is distant from the network’s core because their publications are mostly collaborations with engineers. Third, integrated across these two networks is a set of academic-practitioner relationships (labelled clusters, Figure 2).

An emerging co-authorship network for Project 1 which illustrates nexus-domain expertise in water, energy, and food. Nodes represent authors and those labelled nodes represent researchers in the network. Links represent a co-authoring relationship. Clusters of authors mapped using VOSViewer (co-authorship links are best observed in a full-colour version of article online).

In the context of the project, this co-authorship network indicates a set of emergent collective capabilities. Collectively, relations underpinned trustworthy collaborations and effective communication of complexity surrounding environmental science and policy. Furthermore, already-established relations allowed researchers build their project team, including non-academic partners, at short notice and effectively manage the group through the NN+ funding process:

‘Longstanding links between our two universities is the bottom line. We know each other personally; we tend to work in the same sort of field.

‘[…] It’s a completely pre-existing academic and stakeholder network, which is handy to have when you’ve got to turn around a proposal in a tight timeframe. So, you know, if you’ve got a proto-team already in place you can mobilize it quickly in response to things’ (Project 1 researcher).

These networks indicate not only existing cross-disciplinary capabilities (established connections), but also the potential for new collaborations, based on long-established networks, but made more likely by being funded together. Indeed, this was an aim of the Partnership Grant, to convene and realize transdisciplinary potential. One North-west hub researcher told us that the project was exciting exactly because it was an opportunity to work with co-is that they had long-known, but not published with previously.

Turning to research practice, researchers reported capabilities of pluralism, in the sense of valuing different kinds of knowledge:

‘It’s very easy to have a critical or a meta orientation towards science if you were versed in rudimentary sociology. I don’t think that does you much good. (…) economists or scientists may have models of human action that we find objectionable as social scientists. Rather than going, ‘Okay, well they’re stupid, let’s dismiss it,’ they’re not stupid. Have the courtesy to understand what it is that other people do.’ (Project 1 researcher)

Furthermore, researchers praised the egalitarian ethos in the team (9), demonstrated through collaborative approaches to writing:

‘I don’t think there was a particular hierarchy between us. I would come up with the same copy, and depending on colleagues’ availability, would do the rounds between them. It would come back to me with the edges smoothed and some suggestions for further work to do…. it was a nice mix.’ (Project 1 research associate)

Summarizing, researchers cultivated group capabilities to be humble, plural, egalitarian and reflexive. In particular, our analysis revealed the value of professional networks within academia and with practitioners. While interviewees did not emphasize cross-disciplinary cognitive capabilities, capabilities that allowed them to transgress institutional boundaries were valued. Also valued were capabilities that allowed them to manage the project team, communicate complexity across nexus domains and sustain their own livelihoods through each round of competitive funding.

4.3. Mapping and comparing capabilities across the NN+ partnership programme

4.3.1 Cognitive capabilities

We now report on the capabilities in projects across the portfolio using the heuristic (Section 2, Table 1). The analysis indicates cognitive capabilities are valued in at least three ways. First, the cognitive capability to do research beyond the boundary of researchers’ home disciplines. This capability is about having available the cognitive ability to use or, critically, to learn new ways of doing and knowing research. However, while individual researchers value the possibilities of publishing in new disciplines and journals, this possibility is only available to them because they are part of a research team. The capability to publish across disciplinary lines is collectively held.

| Heuristic component . | Explanation, indicative examples, and sources of evidence . | Indicative references . |

|---|---|---|

| Individual tacit capabilities | Skills, aptitudes, competences, and capabilities to advance career prospects of researchers. Capabilities might include tacit and experiential knowledge accrued by researchers; the capability to build an identity as a researcher. Capabilities to understand complex social and societal factors. Individual leadership, administrative, and coaching capabilities. Capabilities to critique disciplinarity. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 1, 2. | Bozeman et al. (2001) |

| de Oliveira et al. (2019) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Heckman and Corbin (2016) | ||

| Hoffmann et al. (2017) | ||

| Huutoniemi (2010) | ||

| Klein (2006) | ||

| Lau and Pasquini (2008) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Collective capabilities | Collective capabilities to perform collaborative and social practices with stakeholders in society; mutual accountability; distributed ownership and leadership among project participants; collective consensus building and managing tensions; capabilities to build new epistemic communities and cultures of evidence; capabilities for coordination; capabilities to perform ontological work; capabilities to promote interpersonal learning; capabilities to build and maintain networks. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | Barry et al. (2008) |

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Klein (2008) | ||

| Hohl, Knerr and Thompson (2019) | ||

| Lang et al. (2012) | ||

| Michalec et al. (2021) | ||

| Spaapen and van Drooge (2011) | ||

| Talwar et al. (2011) | ||

| Cognitive capabilities | The capabilities required to collectively perform scientific and technical work are central to TD research. For example the capability to publish in a disciplinary journal. Capabilities to differentiate, reconcile and synthesize data and knowledge. Capabilities to perform integrative work. Evidenced through bibliometric indicators, workshop 2. | Boix-Mansilla (2006) |

| Bozeman et al. (2001) | ||

| Bozeman and Corley (2004) | ||

| Molas-Gallart et al. (2014) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Contextual influences | Research sites are constitutive of a diversity of knowledge, values which in turn influence capabilities. Framework accounts for multiple issues, multiple actors, multiple settings of TD research. Assessing variance of goals, expectations, norms, and values of research stakeholders relative to TD research context; issues of structure and situatedness to the fore. Capabilities influenced by personal background of researchers and research participants. Assessment accounts for configuration of prevailing social structures and material conditions. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | De Jong (2011) |

| Feller (2006) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Langfeldt (2006) | ||

| O'Donovan and Smith (2020) | ||

| Oosterlaken (2011) | ||

| Nowotny (2003) |

| Heuristic component . | Explanation, indicative examples, and sources of evidence . | Indicative references . |

|---|---|---|

| Individual tacit capabilities | Skills, aptitudes, competences, and capabilities to advance career prospects of researchers. Capabilities might include tacit and experiential knowledge accrued by researchers; the capability to build an identity as a researcher. Capabilities to understand complex social and societal factors. Individual leadership, administrative, and coaching capabilities. Capabilities to critique disciplinarity. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 1, 2. | Bozeman et al. (2001) |

| de Oliveira et al. (2019) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Heckman and Corbin (2016) | ||

| Hoffmann et al. (2017) | ||

| Huutoniemi (2010) | ||

| Klein (2006) | ||

| Lau and Pasquini (2008) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Collective capabilities | Collective capabilities to perform collaborative and social practices with stakeholders in society; mutual accountability; distributed ownership and leadership among project participants; collective consensus building and managing tensions; capabilities to build new epistemic communities and cultures of evidence; capabilities for coordination; capabilities to perform ontological work; capabilities to promote interpersonal learning; capabilities to build and maintain networks. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | Barry et al. (2008) |

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Klein (2008) | ||

| Hohl, Knerr and Thompson (2019) | ||

| Lang et al. (2012) | ||

| Michalec et al. (2021) | ||

| Spaapen and van Drooge (2011) | ||

| Talwar et al. (2011) | ||

| Cognitive capabilities | The capabilities required to collectively perform scientific and technical work are central to TD research. For example the capability to publish in a disciplinary journal. Capabilities to differentiate, reconcile and synthesize data and knowledge. Capabilities to perform integrative work. Evidenced through bibliometric indicators, workshop 2. | Boix-Mansilla (2006) |

| Bozeman et al. (2001) | ||

| Bozeman and Corley (2004) | ||

| Molas-Gallart et al. (2014) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Contextual influences | Research sites are constitutive of a diversity of knowledge, values which in turn influence capabilities. Framework accounts for multiple issues, multiple actors, multiple settings of TD research. Assessing variance of goals, expectations, norms, and values of research stakeholders relative to TD research context; issues of structure and situatedness to the fore. Capabilities influenced by personal background of researchers and research participants. Assessment accounts for configuration of prevailing social structures and material conditions. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | De Jong (2011) |

| Feller (2006) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Langfeldt (2006) | ||

| O'Donovan and Smith (2020) | ||

| Oosterlaken (2011) | ||

| Nowotny (2003) |

| Heuristic component . | Explanation, indicative examples, and sources of evidence . | Indicative references . |

|---|---|---|

| Individual tacit capabilities | Skills, aptitudes, competences, and capabilities to advance career prospects of researchers. Capabilities might include tacit and experiential knowledge accrued by researchers; the capability to build an identity as a researcher. Capabilities to understand complex social and societal factors. Individual leadership, administrative, and coaching capabilities. Capabilities to critique disciplinarity. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 1, 2. | Bozeman et al. (2001) |

| de Oliveira et al. (2019) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Heckman and Corbin (2016) | ||

| Hoffmann et al. (2017) | ||

| Huutoniemi (2010) | ||

| Klein (2006) | ||

| Lau and Pasquini (2008) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Collective capabilities | Collective capabilities to perform collaborative and social practices with stakeholders in society; mutual accountability; distributed ownership and leadership among project participants; collective consensus building and managing tensions; capabilities to build new epistemic communities and cultures of evidence; capabilities for coordination; capabilities to perform ontological work; capabilities to promote interpersonal learning; capabilities to build and maintain networks. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | Barry et al. (2008) |

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Klein (2008) | ||

| Hohl, Knerr and Thompson (2019) | ||

| Lang et al. (2012) | ||

| Michalec et al. (2021) | ||

| Spaapen and van Drooge (2011) | ||

| Talwar et al. (2011) | ||

| Cognitive capabilities | The capabilities required to collectively perform scientific and technical work are central to TD research. For example the capability to publish in a disciplinary journal. Capabilities to differentiate, reconcile and synthesize data and knowledge. Capabilities to perform integrative work. Evidenced through bibliometric indicators, workshop 2. | Boix-Mansilla (2006) |

| Bozeman et al. (2001) | ||

| Bozeman and Corley (2004) | ||

| Molas-Gallart et al. (2014) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Contextual influences | Research sites are constitutive of a diversity of knowledge, values which in turn influence capabilities. Framework accounts for multiple issues, multiple actors, multiple settings of TD research. Assessing variance of goals, expectations, norms, and values of research stakeholders relative to TD research context; issues of structure and situatedness to the fore. Capabilities influenced by personal background of researchers and research participants. Assessment accounts for configuration of prevailing social structures and material conditions. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | De Jong (2011) |

| Feller (2006) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Langfeldt (2006) | ||

| O'Donovan and Smith (2020) | ||

| Oosterlaken (2011) | ||

| Nowotny (2003) |

| Heuristic component . | Explanation, indicative examples, and sources of evidence . | Indicative references . |

|---|---|---|

| Individual tacit capabilities | Skills, aptitudes, competences, and capabilities to advance career prospects of researchers. Capabilities might include tacit and experiential knowledge accrued by researchers; the capability to build an identity as a researcher. Capabilities to understand complex social and societal factors. Individual leadership, administrative, and coaching capabilities. Capabilities to critique disciplinarity. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 1, 2. | Bozeman et al. (2001) |

| de Oliveira et al. (2019) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Heckman and Corbin (2016) | ||

| Hoffmann et al. (2017) | ||

| Huutoniemi (2010) | ||

| Klein (2006) | ||

| Lau and Pasquini (2008) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Collective capabilities | Collective capabilities to perform collaborative and social practices with stakeholders in society; mutual accountability; distributed ownership and leadership among project participants; collective consensus building and managing tensions; capabilities to build new epistemic communities and cultures of evidence; capabilities for coordination; capabilities to perform ontological work; capabilities to promote interpersonal learning; capabilities to build and maintain networks. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | Barry et al. (2008) |

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Klein (2008) | ||

| Hohl, Knerr and Thompson (2019) | ||

| Lang et al. (2012) | ||

| Michalec et al. (2021) | ||

| Spaapen and van Drooge (2011) | ||

| Talwar et al. (2011) | ||

| Cognitive capabilities | The capabilities required to collectively perform scientific and technical work are central to TD research. For example the capability to publish in a disciplinary journal. Capabilities to differentiate, reconcile and synthesize data and knowledge. Capabilities to perform integrative work. Evidenced through bibliometric indicators, workshop 2. | Boix-Mansilla (2006) |

| Bozeman et al. (2001) | ||

| Bozeman and Corley (2004) | ||

| Molas-Gallart et al. (2014) | ||

| Lyall and Meagher (2012) | ||

| Contextual influences | Research sites are constitutive of a diversity of knowledge, values which in turn influence capabilities. Framework accounts for multiple issues, multiple actors, multiple settings of TD research. Assessing variance of goals, expectations, norms, and values of research stakeholders relative to TD research context; issues of structure and situatedness to the fore. Capabilities influenced by personal background of researchers and research participants. Assessment accounts for configuration of prevailing social structures and material conditions. Evidenced through interviews with researchers, questionnaire, workshop 2. Documentary analysis of research outputs | De Jong (2011) |

| Feller (2006) | ||

| Hansson and Polk (2018) | ||

| Langfeldt (2006) | ||

| O'Donovan and Smith (2020) | ||

| Oosterlaken (2011) | ||

| Nowotny (2003) |

Second, within nexus research settings we found radically different kinds of organizations, procedures, stakeholders, power relations, purposes, and wider political–cultural contexts. These included international assessments, government enquiries, regulatory committees, participatory processes, NGO studies, or social movement activities and accessing data in firms. Researchers valued a cognitive capability to apply known tools and frameworks in situations such as these, in which they were sometimes working for the first time.

Third, we found researchers in Projects 1 and 4 valued a cognitive capability for a sustained appreciation of the particular—assessing social and material practices in specific contexts. This capability urges caution over the implications of generalization. Methodologically this is a capability when investigating interconnections between WEF nexus and represents a novel contribution to traditional quantitative and aggregative nexus methods.

4.3.2 Individual tacit capabilities: engaging with power and structure

Individual capabilities valued by researchers included capabilities of humility, valued in colleagues who ‘[don’t] think somewhere in the back of their minds that they are superior’ (researcher P4), the implication here being that superiority arose when uncertainty was located in the work of others, but not their own; capabilities of pluralism in colleagues who are ‘not particularly holding to any Western way of understanding the data’ (researcher P3); and capabilities to be egalitarian, in colleagues who can ‘(…) learn to listen what the stakeholders need and understand how you can respond to their needs, and not just the project’s’ (researcher P1). In other words, a researcher who strives to identify, engage with or alter existing research priorities power structures.

Leadership was mentioned by several researchers in terms of being able to build and manage a research team and also in terms of instilling an attitude of openness, balance. In the context of these research projects we find it more useful to think about leadership in terms of separate capabilities: managing research, being egalitarian in relation to project participants and being able to sustain values of pluralism in the project.

Researchers value being able to break down the hierarchies traditionally constituted by academic disciplines, social status, seniority and uneven geographies—even if they are not always able to fully realize this. A researcher in Project 4 said:

‘a lot of the funding is directed through the [global north] universities, so although we were able to give our partners money through subcontracts, we were still controlling it. So, in a sense there is some kind of implicit hierarchy that goes with it. (…) Are there ways in which we could support research partners in the global south more directly?’.

What researchers are acknowledging here is a capability to cede power, not merely respecting global south interjections, but actively opening and creating spaces for them. They note that capabilities that might better empower overseas colleagues were absent, or structural impediments were too strong to overcome.

4.3.3 Collective capabilities: valuing networks

Project 1 shows us how capabilities are influenced by the configuration of people, knowledge and resources within research sites. Throughout the portfolio, capabilities like egalitarianism, team management, and trust in collaborations were experienced through practices such as ‘encouraging to ask silly questions’ (researcher P2); ‘not being precious during collaborative writing’ (researcher P1); and ‘managing tensions with respect and positivity’ (practitioner P5). It seems that not only are these capabilities individually held, they are also cultivated through shared concerns, interests, and research cultures.

Significantly, networks provide positive feedback for researchers, strengthening capabilities to conduct TD research:

‘I guess these things have a life of their own. Once you start engaging people and you find people you like and can work with, then you want to do more’ (researcher P2).

Networks can be established in numerous ways, by primary investigators opening access to established academic and policy networks (P1 and P3), through networking grants (P1 and P2), or conferences (P4 and P5). Project networks demonstrate the critical importance of nurturing connections over time. Participants reflected that without pre-established personal networks it is challenging to sustain collaborations once the project finishes. This was the experience of the investigators in P4 and P5, where the connections between the researchers and practitioners were established only shortly before the project start and through professional events rather than personal networks: