-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Melissa C Hofmann, Nancy F Mulligan, Kelly Stevens, Karla A Bell, Chris Condran, Tonya Miller, Tiana Klutz, Marissa Liddell, Carlo Saul, Gail Jensen, LGBTQIA+ Cultural Competence in Physical Therapist Education and Practice: A Qualitative Study From the Patients’ Perspective, Physical Therapy, Volume 104, Issue 10, October 2024, pzae062, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzae062

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of cultural competence and humility among patients of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community in physical therapy. Researchers sought to understand the perspectives of adults over 18 years old who have received physical therapy and identify as a member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

A phenomenological qualitative approach was utilized for this study. Patients were recruited through social media and LGBTQIA+ advocacy organizations across the United States. Twenty-five patients agreed to participate in the study. Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide informed by Campinha-Bacote domains of cultural competence (cultural awareness, skill, knowledge, encounter, and desire) to collect individual experiences, discussions, thoughts, perceptions, and opinions.

Three central themes and subthemes emerged from the data and were categorized according to cultural acceptance (societal impact, implicit and explicit bias), power dynamics between the in-group and out-group (out-group hyperawareness of their otherness), and participant solutions (policy, training, education).

An LGBTQIA+ patient’s experience is influenced by the provider cultural acceptance, and the resulting power dynamics that impact LGBTQIA+ patients’ comfort, trust, and perceptions of care. Enhanced patient experiences were found more prevalent with providers that possessed elevated levels of education or experience with this community, supporting Campinha-Bacote assumption that there is a direct relationship between level of competence in care and effective and culturally responsive service.

Awareness of the underlying issues presented in these themes will assist in the development of effective solutions to improve LGBTQIA+ cultural competence among physical therapists and physical therapist assistants on a systemic level.

Introduction

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community, a marginalized community, includes individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual and gender diverse identities. According to the Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, 11.7% of respondents 18 years or older identify as LGBTQIA+.1 Although this demonstrates an increase in the LGBTQIA+ population compared to previous studies,2 these data still underestimate the population estimate within the United States (US). There is also a lack of emphasis on cultural competence and humility within the health field as LGBTQIA+ individuals avoid seeking medical treatment and disclosing personal information because of the stigma and discrimination that they encounter.3,4

Common health care disparities reported by the LGBTQIA+ community include gender dysphoria and misgendering,3 fear of discrimination, humiliation, and harassment,3,5,6 health care affordability and insurance coverage,3,7 especially for transgender patients.3,5 This population experiences higher risk of infection, mental health conditions, chronic diseases, substance abuse, obesity, cancer, violence, and lack of health care and housing access.5,7,8 The accumulation of environmental elements increases an individual’s exposure to stressors affecting health, including discrimination and a devalued self-perception. This leads to coping mechanisms that include the avoidance of health care and fear of discrimination which leads to poorer physical and psychological health outcomes.9

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of cultural competence and humility among LGBTQIA+ patients in physical therapy. Although Ross et al10 assessed the LGBTQIA+ patient perspective in physical therapy in Australia, results may not be generalizable to the LGBTQIA+ population in the US due to cultural and health system differences in the sample. In the context of this study, refers to a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables effective work in cross-cultural situations,11 while cultural humility refers to a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique to learn about other cultures while also examining one’s own beliefs, cultural identities, assumptions, biases, and values.12,13 Questions posed in this study were guided by Campinha-Bacote model of cultural competence which is comprised of 5 primary constructs; cultural awareness (acknowledgement of biases, prejudices, and assumptions); cultural knowledge (educational foundation of diverse cultural/ethnic communities); cultural skill (accurate performance of a culturally based physical assessment); cultural encounters (engagement with patients from culturally diverse backgrounds); and cultural desire (motivation to engage in domains of cultural competence for culturally diverse communities).14 Researchers chose to inform this study through this model as cultural competence is exemplified through the intersection of these domains, which allow a health care provider (eg, physical therapists) to internalize such constructs and directly impact the patient’s perception of their experience.14

Methods

Design

This study utilized a phenomenological qualitative approach to describe the essence of a physical therapist’s LGBTQIA+ cultural competence (phenomenon) by deriving meaning through the lens of the patient experience.15

Hermeneutic phenomenology (interpretive) seeks to understand the deeper layers of human experience and how the individual’s lifeworld, or the world as they experience it, impacts this experience.16 This approach allowed the researchers to study individuals’ narratives (background) and interpret such narratives to understand the individuals’ experience and decisions in their own lives.17 This type of qualitative inquiry also considers the role of the researcher. The researcher, like the participant, cannot separate from their own lifeworld and thus their past experiences and knowledge provide guidance to the inquiry. Researchers implementing interpretive phenomenology acknowledge their preconceptions and reflect on their subjectivity during the analysis process.18 Due to the exploratory nature of the question and limited literature on the experiences of LGBTQIA+ patients, this approach creates theoretical flexibility by having thematic focus emerge in data collection and analysis.19,20

Participants

Inclusion criteria included individuals 18 years and older who identified with the LGBTQIA+ community, and currently receive or have received physical therapy. Due to the sensitive nature of this population and topic, this study utilized convenience and snowball sampling to recruit participants (N = 25; Table).21 Researchers contacted LGBTQIA+ advocacy organizations across the US to request permission to post an invitation on their social media pages. Organizations that returned a site approval letter received a virtual postcard to post on their social media sites with a QR code or link to the informed consent and demographics form that were approved by the institutional review board at Regis University. Additionally, researchers posted QR codes or link postcards on personal social media channels.

| Demographic Variable (N = 25) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender identity Male Female Transgender woman (male-to-female) Transgender man (female-to-male) Nonbinary or genderqueer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 0 (0) 4 (16) 7 (28) |

| Sexual identity Gay Lesbian Bisexual Queer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 5 (20) 6 (24) |

| Geographic location Northeast Southeast South Midwest Mountain West Coast Outside of US | 4 (16) 4 (16) 1 (4) 2 (8) 9 (36) 5 (20) 0 (0) |

| Race White or Caucasian Hispanic or Latinx Black Asian Mixed | 18 (72) 2 (8) 1 (4) 1 (4) 3 (12) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school Associate degree Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Doctorate degree DPT | 1 (4) 3 (12) 13 (52) 5 (20) 2 (8) 1 (4) |

| Type of provider Physical therapist Physical therapist assistant | 24 (96) 1 (4) |

| Age, y 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 >60 | 10 (40) 10 (40) 3 (12) 2 (8) 0 (0) |

| Demographic Variable (N = 25) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender identity Male Female Transgender woman (male-to-female) Transgender man (female-to-male) Nonbinary or genderqueer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 0 (0) 4 (16) 7 (28) |

| Sexual identity Gay Lesbian Bisexual Queer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 5 (20) 6 (24) |

| Geographic location Northeast Southeast South Midwest Mountain West Coast Outside of US | 4 (16) 4 (16) 1 (4) 2 (8) 9 (36) 5 (20) 0 (0) |

| Race White or Caucasian Hispanic or Latinx Black Asian Mixed | 18 (72) 2 (8) 1 (4) 1 (4) 3 (12) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school Associate degree Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Doctorate degree DPT | 1 (4) 3 (12) 13 (52) 5 (20) 2 (8) 1 (4) |

| Type of provider Physical therapist Physical therapist assistant | 24 (96) 1 (4) |

| Age, y 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 >60 | 10 (40) 10 (40) 3 (12) 2 (8) 0 (0) |

| Demographic Variable (N = 25) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender identity Male Female Transgender woman (male-to-female) Transgender man (female-to-male) Nonbinary or genderqueer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 0 (0) 4 (16) 7 (28) |

| Sexual identity Gay Lesbian Bisexual Queer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 5 (20) 6 (24) |

| Geographic location Northeast Southeast South Midwest Mountain West Coast Outside of US | 4 (16) 4 (16) 1 (4) 2 (8) 9 (36) 5 (20) 0 (0) |

| Race White or Caucasian Hispanic or Latinx Black Asian Mixed | 18 (72) 2 (8) 1 (4) 1 (4) 3 (12) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school Associate degree Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Doctorate degree DPT | 1 (4) 3 (12) 13 (52) 5 (20) 2 (8) 1 (4) |

| Type of provider Physical therapist Physical therapist assistant | 24 (96) 1 (4) |

| Age, y 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 >60 | 10 (40) 10 (40) 3 (12) 2 (8) 0 (0) |

| Demographic Variable (N = 25) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender identity Male Female Transgender woman (male-to-female) Transgender man (female-to-male) Nonbinary or genderqueer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 0 (0) 4 (16) 7 (28) |

| Sexual identity Gay Lesbian Bisexual Queer | 2 (8) 12 (48) 5 (20) 6 (24) |

| Geographic location Northeast Southeast South Midwest Mountain West Coast Outside of US | 4 (16) 4 (16) 1 (4) 2 (8) 9 (36) 5 (20) 0 (0) |

| Race White or Caucasian Hispanic or Latinx Black Asian Mixed | 18 (72) 2 (8) 1 (4) 1 (4) 3 (12) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school Associate degree Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Doctorate degree DPT | 1 (4) 3 (12) 13 (52) 5 (20) 2 (8) 1 (4) |

| Type of provider Physical therapist Physical therapist assistant | 24 (96) 1 (4) |

| Age, y 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 >60 | 10 (40) 10 (40) 3 (12) 2 (8) 0 (0) |

Procedure

All researchers completed a 2-hour training session on the facilitation of focus groups and individual interviews using a training guide developed by Krueger.22 The guide emphasized moderator skills, recorder skills, strategies for questions, note taking, debrief, analysis, transcription, and reporting of results. Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted via the Zoom online audio and video platform (Zoom Video Communications Inc, San Jose, CA, USA).23 The protocol was centered on providing cultural safety for rich discussion, with a strong emphasis on the ground rules (confidentiality, respect, facilitator neutrality, and patient-driven discussion) (Suppl. Material 1, Focus Group/Interview Protocol). To address confidentiality, safety and anonymity, individual interviews were offered, and cameras could remain off. The duration of focus groups was between 1 and 2 hours and was conducted with a maximum of 4 participants and 2 facilitators, while individual interviews were completed by 1 facilitator. Sessions were recorded within Zoom and a secondary recording method and saved to a secure location. All sessions were transcribed verbatim by the investigators, contracted professionals, or transcription software (NVivo; Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA).24 At the conclusion of each focus group and individual interview session, participants received a debrief form that described the study, provided researcher contact information, and crisis/counseling resources.

Data Collection and Analysis

Within the hermeneutic phenomenology framework, data collection and analysis encompassed use of an interpretive process. Five main steps were followed: deciding upon a research question, identification of preunderstandings, gaining understanding through dialogue with participants, gaining understanding through dialogue with text, and establishing trustworthiness.25

Focus group and individual interview sessions were semi-structured in design, with open-ended questions about participants’ experiences to facilitate in-depth discussion while allowing moderators to explore topics further as they emerged. The protocol revolved around the concept of cultural competence as defined by Campinha-Bacote, with questions designed to examine its 5 domains: cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, cultural encounters, and cultural desire.14

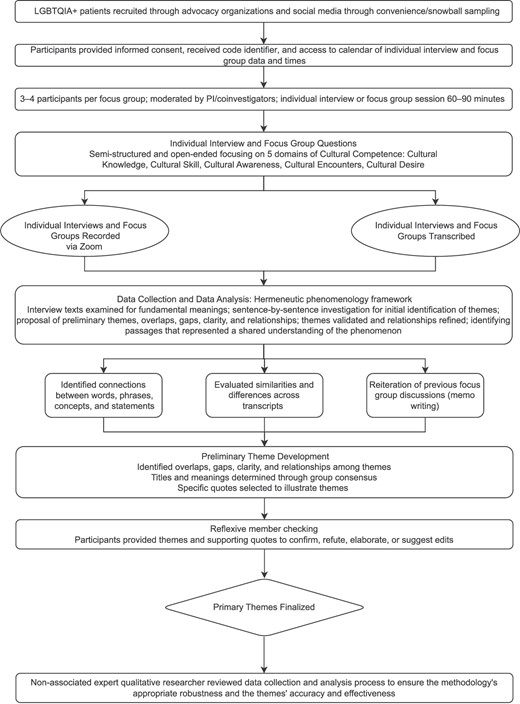

Data analysis involved a constant dialogue between the researcher, participants, data, and literature, which allowed for meanings and insights to emerge. Four primary phases were utilized per Fleming framework. In phase 1, all interview texts were examined to assess the fundamental meaning of the text as a whole. Within a team of 9 investigators, 2 investigators analyzed each focus group and individual interview transcript. During phase 2, every sentence or section was investigated to expose its meaning to understand the subject matter, thus, facilitating identification of themes through participants’ words, phrases, concepts, and statements. Following this phase, every sentence or section was then related to the meaning of the whole text.25 The hermeneutic circle is essential for gaining understanding and must move back to the whole which widens the meaning of the individual parts. Researchers utilized an iterative process by proposing preliminary themes, identifying overlaps, gaps, clarity, and relationships. Researchers met and determined the primary themes and validated and refined relationships upon reaching data saturation.20 When finalizing themes, discrepancies within each pair were discussed and resolved by group consensus. The last step involved identifying passages that were representative of the shared understandings between the researchers and participants and provided further context to the phenomenon being studied. Titles and meanings were determined through group consensus and specific quotes were selected that best exemplified themes (Fig. 1).25

Qualitative flow chart. LGBTQIA+ cultural competence theme development. LGBTQIA+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual; PI = principal investigator.

To further assess the trustworthiness of the data, credibility, dependability, transferability, confirmability, and reflexivity were assessed. Credibility, dependability, and transferability were assessed through analyst triangulation, in which a non-associated expert qualitative researcher reviewed the data collection and analysis process to ensure the robustness of the methodology and the developed themes’ accuracy. To establish confirmability, the researchers documented and discussed their own biases, assumptions, thoughts, and feelings. An expert qualitative researcher reviewed such text to demonstrate how such biases could have influenced the study and findings. Reflexive member checking was performed, whereby participants were provided with researchers’ conclusions and session quotes to confirm, refute, elaborate, or suggest edits (Fig. 1). Finally, reflexivity was demonstrated with recruitment of LGBTQIA+ co-investigators. This provided an outlet for transparency for any preconceptions, assumptions, or values related to the research process.21

Role of Funding Source

The funders played no role in this study’s design, conduct, or reporting.

Results

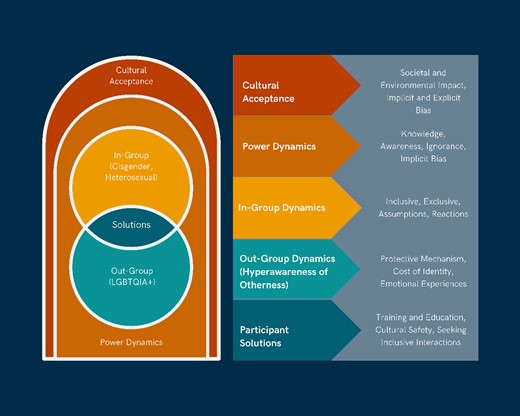

Three central themes and subthemes were identified including cultural acceptance (societal impact, implicit or explicit bias), power dynamics between the in-group and out-group (out-group hyperawareness of their otherness), and participant solutions (policy, training, education) (Fig. 2).

Conceptual model of primary themes. LGBTQIA+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual.

Cultural Acceptance: Foundation of Cultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Desire

Societal Impact, Implicit and Explicit Bias

Participants discussed cultural acceptance as having a significant impact on their interactions with physical therapists who demonstrated implicit and explicit biases. Cultural norms such as the assumption of heteronormativity and lack of knowledge about the LGBTQIA+ community led to situations where LGBTQIA+ patients became hyper aware of their difference from the societal norm. Implicit biases included assumptions about their partner’s gender, misusing pronouns, and asking ignorant questions about their identity or sexuality. For example, when a participant informed her physical therapist, she was married to a woman, the therapist responded, “oh good for you.” This participant reported, “It felt weird, it felt like she didn't know how to react to me….” Participants expressed that these actions, although not meant to be malicious, stemmed from a combination of a lack of exposure to the LGBTQIA+ community and societal heteronormativity. Implicit biases prevented therapeutic rapport, which adversely affected the care the patient received (Suppl. Material 2).

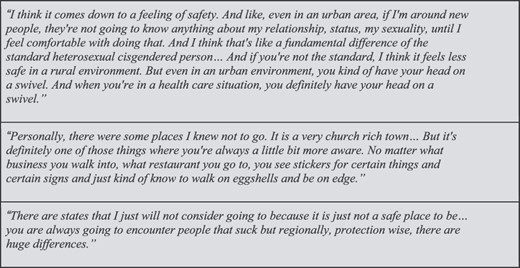

Although all patients experienced implicit bias from their physical therapist, many also endured explicit biases (Fig. 3). Participants described explicit bias stemming from specific regions that included individuals who opposed the existence of and equality for the LGBTQIA+ community. This was discussed as being prominent in but not limited to areas that were more rural, religious, and politically conservative. Such geographical influences and the US legislative state were found to cause safety uncertainty as a transgender participant had to consciously gauge if a physical therapist was a “safe provider to even see.” (Fig. 3). Such biases led to patients feeling unsafe, unseen, and self-conscious of their identity, thus creating a power dynamic that enhanced patient hyper awareness of otherness (Suppl. Material 2).

Power Dynamics

In-Group Power Dynamics: Privilege Reflected in Cultural Encounters

The in-group was described as members exuding positions of privilege, such as those who identify as cis-gender or heterosexual. Participants stated the therapist as part of the in-group, holds the “power” of whether patients feel included or excluded. Participants provided examples where the physical therapist dismissed their unique situation and lacked a desire to gain knowledge and competence to better serve them. For example, 1 participant said, “I had to have physical therapy after top surgery and the PT was like, ‘Well, I don't know how to help you….’” Conversely, positive experiences resulted in a power dynamic that exhibited inclusion of the LGBTQIA+ community. By providing an opportunity to disclose the participant’s preferred gender pronouns, the power dynamic is shared as the participant becomes an active participant in their care. In addition to the therapeutic relationship, the clinical environment also facilitated increased engagement for LGBTQIA+ patients. For instance, a gender-neutral bathroom in a clinic helped a participant “alleviate a lot of…underlying anxieties.” (Fig. 4; Suppl. Material 2).

Out-Group Dynamics: Hyperawareness of Otherness

LGBTQIA+ participants described a hyperawareness of their membership in a minority population, or the out-group. Participants expressed this hyperawareness in negative terms. Feelings could be as minor as general uncomfortableness to significant worry and fear of how the therapist or clinic would react to their sexual and gender identity. This was not always linked to a specific moment, but instead the result of repetitive microaggressions experienced in the clinic setting.26

Body as a Source of Hyperawareness (Appearance, Stereotypes, Boundaries)

Patients characterized the therapist’s attention to the body as an amplifier of body dysphoria or fears of passing as their labeled identity. For some, hyperawareness was invoked simply by the therapist’s gaze on their body. Others expressed even further hyperawareness through the therapist’s interaction with their body in gender dysphoric areas. A participant explained, “In terms of touching my body, I could just sense the tension in them….” Even in situations where the therapist’s physical behavior was correct, the patient’s hyperawareness could be triggered due to culturally ignorant language. Patients described this experience as an uncomfortable juxtaposition of touching and close proximity of bodies and the detached cultural and social connection (Fig. 4; Suppl. Material 2).

Protective Mechanisms to Hyperawareness (Fight, Fawn, Freeze, Flight)

The patients' reactions were often diverse and driven by protective mechanisms to their social identity and emotional well-being. Protective measures were separated into 4 subcategories: fight, fawn, flight, and freeze.27 One of the most common reactions, fight represented a desire to disrupt or overcome the feelings of otherness head-on. Many chose education or advocacy to take control of the scenario and create boundaries.27

The fight response did not have to result in direct confrontation but could be utilized in moments of disruption of the clinic’s norms, such as when filling out intake forms, “I usually do write in and put my pronouns because they almost never ask.” They often corrected the therapist’s use of incorrect pronouns or general candidness about LGBTQIA+ issues. Participants reported that they would “feel seen” when noticing “options for [their] identity” on an intake form and were encouraged that this would inform other therapists on how to properly address and interact with them (Suppl. Material 2).

Fawn, the second most common response to these moments of hyperawareness represented moments when the patient would prioritize the therapists’ feelings or behavior over their own sense of self. Other patients utilized fawning when in a state of emotional fatigue, or when the effort to fight was not worth the potential for an unfavorable outcome.27

The third response, freeze, represented moments of inaction from the patients to their hyperawareness.27 Some used this response to detach from the emotionally challenging moment. Many patients who referenced this response in an attempt to find emotional safety were less public about their identity. Furthermore, other patients described freezing behavior as a result of the emotional exhaustion of repeated macro and micro aggressions. One participant stated, “It’s *exhale* it's very awkward, like I’m not very good at advocating for myself all the time. I usually don’t correct people who misgender me just because it's a little bit exhausting to do it all the time.”

The final response category was flight. Flight corresponds with avoidant behavior.27

Many stated that they “dropped out” of physical therapy due to a therapist’s biases and their inability to be their “authentic” self, which created a sense of not “belonging.” This was described by a participant, “if I … don't have a good feeling with this, I'll just go somewhere else. Frankly, they're not worth my time if they haven't figured it out.” Patients also communicated with other members of the LGBTQIA+ community to filter in or out of clinics (Fig. 4; Suppl. Material 2).

Participant Solutions

Organizational Policy and Education

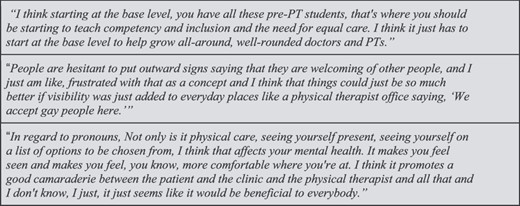

Participants shared ideas on improving the inclusion and belonging of the LGBTQIA+ community in physical therapy. These solutions targeted policy, education, and curriculum to appropriately treat members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Some participants expressed that the governing body of the physical therapist profession, the American Physical Therapy Association, should promote LGBTQIA+ cultural competence as “a standard of care [and] knowledge of our community.”28 Consistent with Copti et al,29 others reported feeling a need for education through DPT coursework prior to becoming a physical therapist. Furthermore, participants expressed the importance of case study integration including LGBTQIA+ patients as a mechanism for students to practice cultural skills when taking a patient history and using appropriate pronouns. In this way, patients would be relieved of the burden of cultural knowledge regarding the LGBTQIA+ community. The mentality of those within the community is that “unless that information is forced [upon the students],” then those who need this education will never understand and change will be difficult to achieve (Fig. 5).

Regarding education for current practitioners, participants suggested continuing education classes and presentations at conferences as practical solutions. However, most participants expressed that “daily repetitive interactions” with those within the community are needed to “adjust their level of consciousness,” and lead to actual change. One participant expressed that transgender people should play a key role in this educational piece because they often experience “changes, hormones, surgery, things like that that you are going to encounter as a PT,” and that education needs to come from those who have lived through these experiences. Participants expressed that much of the implicit bias was produced by a lack of awareness and encounters with the LGBTQIA+ community, thus solutions should involve increased exposure and opportunities for practice (Suppl. Material 2; Fig. 5).

Environmental Changes

Patients expressed appreciation and sought out mechanisms that indicated they were welcome when seeking treatment. Participants were aware of signs and indicators of inclusive and culturally competent providers and described the “ritual” of checking the provider’s website to see if there was any indication of cultural competence within the clinic. Examples included pride flags, clinician pronoun badges, options to note pronouns and preferred names on intake forms, and the implementation of gender-neutral bathrooms. Participants stated that a simple detail such as a neutral bathroom would enhance safety and promote a welcoming environment (Suppl. Material 2).

Discussion

This study utilized a phenomenological approach to explore the experiences of cultural competence among patients of the LGBTQIA+ community in physical therapy. Although questions were guided by the 5 domains of Campinha-Bacote model of cultural competence, patient responses reflected a conceptual model that demonstrated a relationship between cultural acceptance of providers, differences in privilege between the provider and the patients, and resulting power dynamics within and across the dominant in-group and marginalized out-group. How a physical therapist negotiated this power gap often reflected their cultural competency and humility. A bridging of the power dynamic more often resulted in a positive patient experience, while ignorance or avoidance of the dynamic resulted in a negative experience and the feeling of hyperawareness of otherness.

Cultural Acceptance as a Driver of Cultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Desire

Cultural acceptance was consistently referenced by participants as having a significant impact on implicit and explicit biases demonstrated by their physical therapists. This interaction between the social environment and the biases experienced by LGBTQIA+ individuals has been well documented in the literature.9,30–34 Similar to our study, previous studies discussed LGBTQIA+ participants that experienced provider biases when seeking health care which resulted in unfair treatment, discrimination, and diminished care.10,31

The political climate has been shown to impact the cultural acceptance of the LGBTQIA+ community.30 According to the United States Transgender Survey,30 the political issues most important to transgender individuals were protections against violence toward transgender people, insurance coverage of transgender care, parenting and adoption rights, prohibiting conversion therapy, and marriage recognition. Many of our participants reported feeling uncomfortable in areas where the majority voted for politicians that opposed their rights.

Previous research has outlined ways in which cultural desire contributes to engagement with and care for the LGBTQIA+ community. Cultural exclusion of the LGBTQIA+ community leads to providers who are uneducated and incompetent in the treatment of the LGBTQIA+ community. This was depicted in the United States Transgender Survey where 24% reported their primary provider knew “almost nothing” about transgender health care and had to teach their provider to receive appropriate care, while 15% reported providers asked unnecessary and invasive questions.31 This corresponds with Campinha-Bacote conclusion regarding the interdependence of cultural desire to the other constructs of cultural competency.14

Power Dynamics

The power dynamics during cultural encounters between patient and physical therapist played a pivotal role both positively and negatively in the participants’ experience. Some participants experienced a sense of devaluation in the clinic due to being a part of the LGBTQIA+ community which created a power inequity between the patient and the physical therapist, impacting the relationship and thus the care provided.

Although both our work and Casanova-Perez et al31 noted power inequity, a chief difference between the 2 was how power inequity was perceived by patients. In Casanova-Perez et al,31 patients were judged to not be smart enough to understand medical decisions.31 Our work illustrated that patients described feeling that the provider did not know enough about their specific medical needs and were burdened with the role of educator. This difference in experience could be tied to the type of provider involved as Casanova-Perez et al31 examined the health care system across multiple provider types (physicians, nurses, pharmacists). Despite the difference in setting, both papers rooted these patient–provider interactions because of systemic inequality in power.

A power dynamic that encourages a positive experience for patients is supported by literature. A study completed in 2020 interviewed patients with chronic diseases and health care professionals to study the values that influence power dynamics.35 Such patients developed knowledge and an ability to recognize competent providers and were thus empowered to fight to be understood.35 Participants in this study expressed the importance of culturally skilled care and that their identity should be prioritized when developing a plan of care.

In-Group Dynamics

Multiple authors have recognized that social identities are relational, meaning that groups define themselves in relation to others and are tied to the surrounding power dynamics.36–38 This phenomenon of cultural minimization results in implicit bias and a perception of inferior quality of care from patients. When examining LGBTQIA+ research, heterosexual and cis normative assumptions have been documented in several descriptions of general health care experiences31,39–41; however, our research appears to be the first that looked at this concept specifically within physical therapy. Other literature identified uncomfortable or unwelcomed conduct identified by patients including non-inclusive paperwork, intrusive questions, inappropriate comments, or lack of understanding of LGBTQIA+ specific concerns.37–39 These experiences were consistent with our research and point to concerns to address when seeking culturally competent solutions. Although negative experiences with providers were prevalent in our research, participants also mentioned factors that led to a positive experience. In positive patient experiences, the domains of cultural competence were evident through the physical therapists’ active listening (skill), previous experience with this population (encounters), non-assumptive communication (awareness and knowledge), and overt displays of respect (desire).31,39–41

Out-Group Dynamics

During negative interactions with practitioners, patients often experienced apprehension and an acute awareness of their “hyperawareness of otherness.” In their work on stigma, Major and O’Brien identified this experience as an appraisal of surroundings to determine threats to one’s social identity.42 Other literature focusing on cultural barriers to competent care have noted minority populations’ (Black, Indigenous, and people of color, women, and LGBTQIA+ people) attention toward identity threats while in medical spaces.43–45 Although patient’s hyperawareness of otherness begins as a vigilance tactic, when met with a perceived threat, patients exhibited 1 of 4 protective mechanisms or coping strategies (freeze, fight, fawn, flight).27 Casanova-Perez et al31 noted a similar patient response when met with unfair treatment. Although their work split these responses into 2 categories of active and passive, both works connect this response to a feeling of “otherness,” that is a sharp distinction between the provider’s community and that of the patients.31 Other authors expanded the framework to include these coping mechanisms as a result of chronic vigilance for discrimination, even in the absence of actual discriminatory cues.45,46 Our work serves to connect the quantitative results from these other studies with actual patient descriptions of vigilance, stress, and coping, demonstrating that these responses are not unique to merely the profession of physical therapy, but the health care system as a whole.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Data saturation was deemed complete when no new information had emerged, despite a limited sample size (N = 25). According to Stark and Trinidad, a sample size in phenomenology research that involves interest in the lived experiences of individuals who experience the same phenomenon, may be only a few participants who can provide an in-depth view of their experience. Thus, the sample size may range from 1 to 10 participants.47 The participant pool lacked geographical and racial diversity, which diminished the generalizability of the results. Although the sample was perhaps not representative of experiences across the country, the themes reflected these individuals’ lived experiences. Furthermore, due to several of the facilitators having personal relationships with the content of the research, inherent bias may have been present; however, this bias was controlled for through reflexivity, member checking, and triangulation methods.

Recommendations for Action and Future Research

This research demonstrates meaningful actions that can be taken by physical therapists to improve the patient’s experience. These include: (1) advocacy for the LGBTQIA+ community at the local, state, and national levels to address regional differences in LGBTQIA+ legal protections and cultural climate; (2) creating and utilizing LGBTQIA+ educational resource materials for clinicians and students; (3) seeking opportunities to interact and learn from individuals in the LGBTQIA+ community; (4) utilizing preclinical paperwork that asks the patient’s sexual and gender identity and preferred pronouns; (5) displaying inclusive images on websites or in clinic areas; (6) providing access to gender neutral bathrooms; and (7) building a therapy alliance on trust and eagerness to learn about the physical therapy needs of the LGBTQIA+ community.

Further research is warranted to fully understand and determine how to improve the experiences of the LGBTQIA+ community. Research on patients’ perspectives with a larger sample size, greater racial and geographic distribution, and larger age range is necessary. Our research excluded individuals under the age of 18, thus research on the experiences of teenagers and pediatric patients specifically is called for to fully illustrate the climate. And finally, research to implement and determine the effectiveness of proposed solutions is needed.

Conclusion

An LGBTQIA+ patient’s experience is influenced by the cultural acceptance on the part of the provider, and the resulting power dynamics that impact LGBTQIA+ patients’ comfort, trust, and perceptions of care. Enhanced patient experiences were found more prevalent with providers that possessed elevated levels of education or experience with this community, supporting Campinha-Bacote assumption that there is a direct relationship between level of competence in care and effective and culturally responsive service. This research adds further evidence that awareness of underlying issues in LGBTQIA+ patient experiences will assist in the development of solutions to increase cultural competence among physical therapists and physical therapist assistants on a systemic level.

Author Contributions

Melissa C. Hofmann (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Nancy F. Mulligan (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Kelly Stevens (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Karla A. Bell (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Chris Condran (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Tonya Miller (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Tiana Klutz (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Marissa Liddell (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Carlo Saul (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), and Gail Jensen (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing).

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Regis University.

Funding

Regis University College Research and Scholarship Committee (CRS) contributed funding to this study.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

Zoom Video conferencing, web conferencing, webinars, screen sharing. Zoom Video. 2022. Accessed July 31, 2023. https://zoom.us/.

Comments