-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Josh W Faulkner, Deborah L Snell, A Framework for Understanding the Contribution of Psychosocial Factors in Biopsychosocial Explanatory Models of Persistent Postconcussion Symptoms, Physical Therapy, Volume 103, Issue 2, February 2023, pzac156, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac156

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Biopsychosocial models are currently used to explain the development of persistent postconcussion symptoms (PPCS) following concussion. These models support a holistic multidisciplinary management of postconcussion symptoms. One catalyst for the development of these models is the consistently strong evidence pertaining to the role of psychological factors in the development of PPCS. However, when applying biopsychosocial models in clinical practice, understanding and addressing the influence of psychological factors in PPCS can be challenging for clinicians. Accordingly, the objective of this article is to support clinicians in this process. In this Perspective article, we discuss current understandings of the main psychological factors involved in PPCS in adults and summarize these into 5 interrelated tenets: preinjury psychosocial vulnerabilities, psychological distress following concussion, environment and contextual factors, transdiagnostic processes, and the role of learning principles. With these tenets in mind, an explanation of how PPCS develop in one person but not in another is proposed. The application of these tenets in clinical practice is then outlined. Guidance is provided on how these tenets can be used to identify psychosocial risk factors, derive predictions, and mitigate the development of PPCS after concussion from a psychological perspective within biopsychosocial conceptualizations.

This Perspective helps clinicians apply biopsychosocial explanatory models to the clinical management of concussion, providing summary tenets that can guide hypothesis testing, assessment, and treatment.

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines concussion/mild traumatic brain injury as an “acute brain injury resulting from mechanical energy to the head from external physical forces,” with any of the following: confusion or disorientation, loss of consciousness not exceeding 30 minutes, posttraumatic amnesia for less than 24 hours, Glasgow Coma Scale between 13 and 15 after 30 minutes postinjury, and/or other transient neurologic abnormalities (ie, focal signs, seizure, and intracranial lesion not requiring surgery).1 Following a concussion, some individuals may experience persistent postconcussion symptoms (PPCS). The clinical management and treatment of PPCS can be a challenging endeavor for clinicians in rehabilitation settings. Recently an expert consensus defined PPCS as the presence of any symptom that cannot be attributed to a preexisting condition, that appeared within hours of concussion, that is still present every day 3 months after the trauma, and has an impact on at least 1 aspect of a person’s life.2 Historically, it was believed only a small minority of individuals experienced PPCS.3 However, recent evidence has challenged this and PPCS are likely to be far more prevalent.4,5 For example, in a community-based longitudinal study (N = 341), Theadom and colleagues5 found that nearly half of participants (47.9%) were experiencing 4 or more postconcussion symptoms 1 year postinjury. The consequences of persistent symptoms can be profound, causing significant disruptions to well-being, functioning, and quality of life.6

Despite growing recognition and awareness, there is a need to support clinicians to understand how PPCS develop and to identify those at risk. Current explanatory models of PPCS propose a biopsychosocial approach.7–10 The development of such models has been catalyzed by consistent evidence pertaining to the role of psychosocial factors in concussion recovery.11–13 In short, these biopsychosocial models highlight the role of preinjury vulnerabilities, early physiological effects induced by concussion, and the role of other postinjury factors, such as psychological reactions, psychosocial stressors, coping strategies, and medicolegal issues.8–10 These models have been influential. Clinically, they advocate for a multidisciplinary approach to concussion management. Additionally, they have precipitated a shift in the conceptualization of concussion recovery. It has been argued that the historically used term “postconcussion syndrome” is unhelpful. Referring to these symptoms as a syndrome implies a common underlying cause no longer supported by current evidence.14 A biopsychosocial explanation ensures all factors known to impact recovery are highlighted, with the injury being just one of these.

However, biopsychosocial models of concussion have varying degrees of clinical utility, challenged by the heterogeneous and complex nature of PPCS. These models are often comprehensive, complex, and difficult to present to patients in a succinct and accessible manner. This is particularly pertinent from a psychological perspective. It can be challenging for patients and clinicians to identify and understand the role of psychological factors within these biopsychosocial frameworks. This in part is driven by a tendency of these models to operationalize psychological factors into broad diagnostic entities (ie, anxiety, depression, stress) without explanatory depth detailing how these broad psychological categories develop and transpire over time to influence recovery.

Clinically, this can have significant implications. When a patient is referred for rehabilitation, it can be challenging for clinicians to understand, identify, and address the underlying causal processes that result in the development and maintenance of psychological factors within biopsychosocial frameworks. This can impact the provision of optimal treatment. Furthermore, discussing the role of psychological factors in concussion recovery, without such an understanding, has the potential to impact therapeutic rapport and patient engagement. Patients may feel that their beliefs regarding their injury are challenged when such discussions occur. Thus, in rehabilitation, there may be a tendency to avoid focusing on the psychosocial aspects of concussion recovery, which can impact successful recovery outcomes. This is also incongruent with consensus concussion treatment guidelines stipulating the importance of addressing psychological factors in concussion care.15,16

Thus, the overall objective of this Perspective article is to support clinicians in rehabilitation settings, including physical therapists and occupational therapists, to identify, address, and where appropriate, manage psychological factors within biopsychosocial explanatory models of PPCS in adults. To achieve this, we propose that current understandings of psychological factors in concussion recovery can be summarized into 5 tenets. We then discuss the application of these tenets in clinical practice to identify PPCS risk and guide concussion management from a psychological perspective. Importantly, this framework does not negate the importance of other biopsychosocial factors on concussion recovery. There is evidence that an array of other nonpsychological factors may contribute to the development of PPCS and thus need to be considered and, if possible, addressed in concussion management. Thus, in this Perspective article, we aim to provide a lens over the psychological components of biopsychosocial models of PPCS and provide a framework to assist all clinicians involved in concussion care and treatment.

Unraveling the Complexities of PPCS

Applying a psychological lens to the biopsychosocial conceptualization of PPCS can be challenging. To support clinicians in this endeavor and to enhance the clinical applicability of the proposed framework, we first provide 2 fictional case studies inspired by clinical observations. These cases are interwoven in subsequent discussions to provide a bridge between theory and clinical practice.

Case 1: Ella

On a Friday morning, Ella, a 37-year-old school teacher, tripped in the kitchen and her head impacted an open drawer. There was no loss of consciousness, but Ella felt disoriented and confused; she had an instant headache. That day, Ella took her children to sports and then visited a friend. Ella’s head pain worsened as the day continued, and she became fatigued, light-sensitive, and struggled to concentrate. She was highly irritable and felt very emotional. The following day, Ella’s symptoms were still present; however, she had to complete several chores and had no time to rest. On Monday, Ella presented to her general practitioner where she was diagnosed with a concussion and referred to an outpatient clinic for rehabilitation.

Ella’s general practitioner recommended 2 days off work and then reduced hours until reviewed at the concussion clinic. However, Ella was worried about taking time off work. She had previous difficulties with her manager when she had to take time off when struggling through her divorce; she was anxious about work and, therefore, decided not to disclose her injury to her manager. After taking 2 days off, Ella returned to full-time work. After a few days, Ella’s symptoms were increasing and she was struggling with work and home demands. She was stressed and struggling to cope; she was scared that there was something seriously wrong. She consequently called the concussion clinic and an appointment was brought forward. She was assessed and a concussion rehabilitation plan was formulated. This included regular input from an occupational therapist, as well as physical therapist treatment, with a focus on education, pacing, scheduling, and a graduated return to activity. It was agreed that Ella would work at reduced hours with a plan to increase these over time.

Initially, Ella was feeling positive and optimistic; she was relieved to have support in place. Soon Ella started to worry about her ability to cope and manage work and home life. This became salient after Ella had a “bad day” at work. She had decided to do a few extra hours at work as a colleague was away. Ella was feeling anxious at work and consequently wanted to show her manager she was capable. The following day Ella had an “excruciating” headache and she felt very emotional. Regardless, Ella continued to work but she now felt heightened stress. In consultation with her concussion treatment team, it was agreed that Ella would take a week off work. A plan for the week was formulated with a focus on engaging in light activities, including some work-related tasks, with scheduled breaks and rest periods. Ella tried to follow the plan but she was riddled with anxiety and embarrassment and was ruminating about work. She was concerned about recommencing work but felt pressure to return for financial reasons. Despite the education provided, Ella worried that engaging in activities would increase her symptoms; she consequently stopped these and mainly stayed in bed. Ella’s attempts to return to work on reduced hours were unsuccessful even though increased input from her concussion treatment team was provided. Ella had panic attacks before starting work, and at lunchtime she would need to sleep. She felt constantly anxious and she worried that her work performance was being scrutinized. Consequently, Ella was not able to manage most work tasks and was falling behind; she was concerned she would lose her job. Ella was low in mood and felt hopeless; she believed she would never get better. Three months after her injury, she again presented to her general practitioner who deemed her medically unfit to work and she was referred to a rehabilitation physician to review her “worsening symptoms.”

Case 2: Jessica

Jessica (35 years old), works at a department store and lives with her husband and son. Jessica is an active person and has been an avid runner throughout her life. Jessica did well at school, and it was there that her love of sport, and in particular running, developed. Jessica has no formal history of mental health difficulties. She broke her leg at age 15 and experienced some low mood at the time. Jessica was pragmatic and diligent with her rehabilitation and she was back running the following year.

Whilst playing netball, Jessica’s head collided with another player. There was no loss of consciousness, but she was disoriented, confused, and had head pain. Jessica had little recollection of the remainder of the game. For the rest of the day, she was fatigued, nauseous, and her headache intensified. She rested and went to bed early. The following day was similar with ongoing symptoms; she was also irritable and uncharacteristically emotional. Jessica worried there might be something seriously wrong and made an appointment with her general practitioner. Jessica’s husband attended the appointment, where she was diagnosed with a concussion and referred to an outpatient clinic for rehabilitation. Her general practitioner recommended a further 2 days off work and then to return to work on reduced hours.

Jessica followed her general practitioner’s advice and she spoke with her manager regarding her injury. They were supportive of her working reduced hours, as well as taking extra short breaks when needed; it was also suggested she work in a quieter environment. After work, Jessica had a headache, fatigue, and was slightly irritable. She would go home and rest, and then go for a light walk. Jessica continued in this pattern for the next 2 weeks. At times, her symptoms were still noticeable, especially fatigue, and this continued to be a source of frustration as she wanted to return to running. However, Jessica was noticing improvements and was hopeful about her recovery. Two weeks postinjury, Jessica was seen at the concussion clinic. She was assessed and a rehabilitation plan was formulated. This included regular input from an occupational therapist, as well as physical therapy. Treatment included education, pacing, scheduling, and a graduated return to activity. Jessica implemented the treatment plan and was diligent in following the derived schedule. Jessica had a couple of “bad days,” which were frustrating; however, she recalled the education provided and recognized she had done too much. She would then put in place strategies to manage this. For example, on one occasion when her symptoms were particularly salient she cancelled lunch with a friend and took a day off work. These strategies were beneficial and with ongoing adherence to the treatment plan over time, Jessica noticed that overall she was feeling much better. Jessica had ongoing appointments with her concussion treatment team and given the improvements was keen to return to work full time. However, her team continued to advise a gradual increase in working hours and a supported return to cardiovascular activity, as her fatigue and the occasional headache were still present. Jessica followed this advice and over the next month with ongoing treatment, her improvements continued. She was back working full-time 2 months after her injury.

Explaining PPCS From a Psychological Perspective: The 5 Tenets

Based on current evidence, we propose 5 interrelated tenets to explain the role of psychological factors in the development of PPCS within current biopsychosocial conceptualizations. These tenets provide a framework to understand, from a psychological perspective, why Ella develops PPCS and Jessica does not, despite having experienced a similar injury and similar early rehabilitation input. The identification of these tenets was inspired by drawing on the following: (1) the interrelated facets of concussion recovery, (2) the similarities between PPCS and chronic pain, and (3) the unique pathophysiology of a concussion. First, in order to apply a psychological lens to the biopsychosocial explanations of PPCS there must an appreciation of the various interrelated facets that contribute to PPCS, including injury and postinjury factors, as well as the contributing roles of preinjury vulnerabilities and functioning.14,17,18 Second, similarities between PPCS and chronic pain have been established because both phenomena represent an acute to chronic symptomology pathway.19 Detailed psychological explanatory frameworks have been proposed to explain the development of chronic pain within biopsychosocial models. These frameworks draw on well-established evidence-based explanations. Thus, our proposed framework was also inspired by the psychological theories (ie, psychosocial vulnerabilities, transdiagnostic processes, psychological learning paradigms) highlighted in these chronic pain models.19,20 However, reliance exclusively on the chronic pain literature was unlikely to produce an effective psychological explanatory model for concussion. Unlike a musculoskeletal injury, a concussion can have physiological consequences on the brain regions directly responsible for the psychological factors highlighted in biopsychosocial explanatory models of PPCS.21 Thus, it was also essential that the proposed framework also drew on current pathophysiological explanations of concussion, as well as the metabolic implications that activity has on recovery and psychological functioning postinjury.

Tenet 1: Preinjury Psychological Vulnerabilities

Specific preinjury psychological vulnerabilities are associated with PPCS. A consistent theme in the scientific literature regarding risk factors for PPCS is a preinjury mental health condition. There is strong evidence this predicts worse long-term concussion outcomes.10–12 Following a concussion, a preinjury mental health condition is associated with greater endorsement of symptoms and functional disability.7,22 Interestingly, Karr and colleagues17 found that individuals with preinjury anxiety or depression did not differ in their perceived change in symptom severity following injury (postinjury minus preinjury symptom ratings). It was, therefore, suggested that greater concussion symptom severity in these individuals may represent a continuation of preinjury symptom elevations. Furthermore, mental health history is associated with a greater risk of developing emotional disturbances following concussion,23 worsening of a preexisting mental health condition,24 and development of a new mental health condition.25

Specific preinjury personality traits may also contribute to concussion outcomes. Originally, Kay et al26 suggested perfectionism, grandiosity, and unmet dependency traits are possible risk factors. Garden and colleagues27 found that negativistic, dependent, sadistic, somatic, and borderline personality traits were associated with increased self-reported postconcussion symptoms. These personality traits may influence an individual’s interpretation of their injury, symptoms, and recovery. Personality traits can also contribute to an individual’s coping style,28 and the overreliance on certain coping behaviors, such as avoidant coping, has also been associated with concussion recovery.29 Finally, preinjury resilience, which is broadly defined as positive adaptation and the ability to “bounce back,” may also influence concussion outcomes.30

With regard to our case studies, Ella had a preinjury diagnosis of anxiety and depression. It could be speculated that Ella may also have specific personality traits in accordance with a more anxious temperament. Ella experienced recent psychosocial stressors (a divorce), which precipitated mental health difficulties. These preinjury stressors and the mental health consequences of these had a significant impact on Ella’s behavior following her concussion. Ella was anxious and worried about returning to work given her historical experiences. These psychological factors have a significant impact on her behavior and rehabilitation. In addition, Ella is prone to using coping behaviors not conducive to managing elevated psychological distress. We can see this play out following her injury. Under heightened emotional distress, Ella had a tendency to utilize avoidant coping strategies (ie, initially not telling her manager about her injury) to manage this. In contrast, Jessica had greater psychological wellness before her injury. She had a more solutions-focused approach to managing stressors with adaptive coping strategies (ie, exercise). Ella’s preinjury psychological risk factors may have therefore increased the severity of her acute postconcussion symptoms.

Tenet 2: Acute Psychological Distress

Ella and Jessica both experienced psychological distress following their injuries. Here, psychological distress is a term that encapsulates nonspecific symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression.31 Heightened emotional expression and lability occur in both presentations. Early after a concussion, psychological distress is common, with prevalence estimates of emotional symptoms (depression, anxiety, irritability) ranging from 49% to 63%.32 Acute psychological distress is associated with postconcussion symptom severity.33 This relationship is likely to be bidirectional, with postconcussion symptoms contributing to psychological symptoms and vice versa.34 Postconcussion symptoms are nonspecific and their presence can be intensified and maintained by other factors, with psychological difficulties being one of these.12 Postconcussion symptoms are common features of psychological disorders, such as major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders.35 Hence, this relationship may also reflect symptom overlap. Based on available evidence, it could be surmised that Ella’s heightened psychological distress postinjury influenced the severity of her initial postconcussion symptoms. An increase in PPCS severity was noted when Ella was anxious about returning to work. This was not evident in Jessica’s presentation. An increase in PPCS severity in the acute phase of the injury can increase risk of developing PPCS.36

The basis of the relationship between postconcussion symptoms and psychological distress is multifactorial but may be explained, to some degree, by the injury itself. In brief, concussion results in cellular and axonal injury, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction.21 These acute physiological changes result in a sudden “energy crisis,” which contributes to affective symptoms.37 Advancements in neuroimaging techniques illustrate how pathology can occur in brain networks associated with mental health (ie, the default mode network that is involved in emotion regulation) resulting in early emotional symptoms.38

Despite these findings, it must be emphasized that concussion cannot be viewed as the only causal factor in the relationship between postconcussion symptoms and psychological distress. Concussion and its consequences can precipitate an acute stress reaction,39 and this was evident in Ella’s case. It is challenging to tease out neurobiological changes associated with concussion from those induced by psychological states, for example, the physiological changes that are involved in stress reactions.34 Additional layers of complexity include the role of preinjury psychosocial vulnerabilities (Tenet 1), and the severity of the injury is not consistently associated with concussion outcomes.10

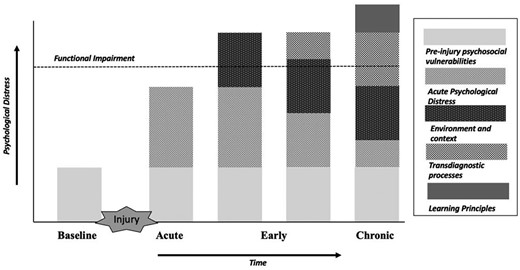

The facets of concussion recovery illustrating how psychological factors contribute to the development and maintenance of psychological distress and impact outcomes over time in concussion. Adapted from the model proposed by Richards et al.14

Tenet 3: Environment and Contextual Factors

Environmental demands are critical in concussion recovery. Physical and cognitive activities have a direct impact on the brain’s ability to restore physiological changes. It has long been observed that postconcussion symptoms can be exacerbated by vigorous physical activity40 and mental exertion.41 This pattern is common in the early stages, as seen in both Ella’s and Jessica’s examples. Therefore, optimizing the balance between symptom severity and physical and cognitive demands is essential.42 However, environmental demands constantly change. This results in symptom fluctuation in part due to the brain being placed under excessive neurometabolic demand.43 Symptoms can thus be perceived as unpredictable, unexpected, and confusing. Psychological distress in the early stages of recovery (see Tenet 2), can then be exacerbated under these conditions.

The fluctuation of postconcussion symptom severity over time has fundamental implications for understanding how PPCS develop. PPCS do not simply occur; they develop and transpire over time.44 Environmental demands had a significant impact on Ella’s recovery. Immediately after her injury, she had numerous commitments and was not able to reduce her activity to manage her symptoms. Her anxiety and worry also drove her to return to full-time work despite the recommendations of her rehabilitation team. Her symptoms intensified when placed under excessive metabolic demand. This then precipitated additional psychological distress due to the consequences this had for her functioning. Ella’s life before her injury was already stressful; however, having to manage and cope in this environment, whilst experiencing symptoms, quickly became unbearable. Thus, following her injury, Ella was in an environment that greatly exceeded her capacity to cope. In contrast, Jessica adhered to the rehabilitation plan and made adaptive modifications to her activities and environment. Despite some initial challenges in managing exacerbations in symptoms, she was able to draw on education and supports to ensure her environment and activity levels were optimal.

Tenet 4: Transdiagnostic Processes

A transdiagnostic approach proposes that underlying psychological processes cause psychological disorders.45 It has been applied to understand psychopathology in a range of conditions, including chronic pain46 and acquired brain injury.47 Transdiagnostic processes can be broadly categorized into cognitive, behavioral, and emotional domains.45 A summary of the processes that have been investigated in concussion is presented in Table 1. Transdiagnostic processes explain the progression of co-occurring problems that often manifest with PPCS. For example, underlying psychological processes, such as catastrophizing and avoidance, can contribute to both PPCS and anxiety.48 Psychological processes transgress diagnostic boundaries and, therefore, targeting will optimize outcomes.49

Summary of Transdiagnostic Processes That Have Been Investigated in Concussiona

| Domain . | Transdiagnostic Process Investigated in PPCS . |

|---|---|

| Cognitive processes relate to thought processes, schemas, core beliefs, attention processes, or reasoning processes | Catastrophizing: the tendency to magnify a perceived threat and overestimate the seriousness of its potential consequences50, Illness perceptions: cognitive appraisal and personal understanding of a medical condition and its potential consequences33,51, Expectation as etiology: following an injury, an individual’s anticipation or expectation of specific symptoms might cause them to misattribute future normal, everyday symptoms to the injury, or fail to appreciate the relationship between more proximal factors (eg, life stress, poor sleep, low mood) and their symptoms52, Good-old day bias: the tendency to view oneself as being healthier before the injury and then underestimate historical difficulties53, Perceived injustice: a belief that one has been treated unfairly, disrespectfully and is suffering unnecessarily as a result of another person’s actions54 |

| Behavioral processes compromising behavioral tendencies such as addiction, behavioral avoidance, behaviors caused by emotional arousal (eg, self-harm), reinforcement, behavioral activation | All or nothing behaviors: a behavioral response to symptoms where patients overdo things when they believe symptoms are abating and then spend prolonged periods recovering when symptoms reappear51,55, Psychological flexibility: the pursuit of values despite the presence of pain or distress. It involves adapting to changing situational demands, allocating mental resources, shifting perspective, and finding balance amongst competing demands56, Avoidance: refers to directing attention away from possibly threatening stimuli and toward stimuli that have the potential to offer safety48,57, Compensation seeking: behaviors to receive financial compensation as a result of an act or injury58 |

| Emotional processes are related to negative affect, emotional (dys)regulation, emotional expression, rejection and intolerance of emotional experiences, acceptance and attendance to emotional experiences, emotional knowledge, emotional contact, or experiencing | Intolerance of uncertainty: a tendency to react negatively on an emotional, cognitive, and behavioral level to uncertain situations59, Anxiety sensitivity: fear of arousal-related bodily sensations, arising from beliefs about the meaning of the sensations. People with high levels of anxiety sensitivity tend to believe that arousal-related bodily sensations are dangerous60, Alexithymia: a cluster of traits characterized by difficulty identifying feelings, describing and identifying emotions, externally oriented thinking, and limited capacity for imaginal thinking61, Neuroticism: a personality trait characterized by a strong tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger. Individuals with this trait have considerable difficulties in coping with stress62 |

| Domain . | Transdiagnostic Process Investigated in PPCS . |

|---|---|

| Cognitive processes relate to thought processes, schemas, core beliefs, attention processes, or reasoning processes | Catastrophizing: the tendency to magnify a perceived threat and overestimate the seriousness of its potential consequences50, Illness perceptions: cognitive appraisal and personal understanding of a medical condition and its potential consequences33,51, Expectation as etiology: following an injury, an individual’s anticipation or expectation of specific symptoms might cause them to misattribute future normal, everyday symptoms to the injury, or fail to appreciate the relationship between more proximal factors (eg, life stress, poor sleep, low mood) and their symptoms52, Good-old day bias: the tendency to view oneself as being healthier before the injury and then underestimate historical difficulties53, Perceived injustice: a belief that one has been treated unfairly, disrespectfully and is suffering unnecessarily as a result of another person’s actions54 |

| Behavioral processes compromising behavioral tendencies such as addiction, behavioral avoidance, behaviors caused by emotional arousal (eg, self-harm), reinforcement, behavioral activation | All or nothing behaviors: a behavioral response to symptoms where patients overdo things when they believe symptoms are abating and then spend prolonged periods recovering when symptoms reappear51,55, Psychological flexibility: the pursuit of values despite the presence of pain or distress. It involves adapting to changing situational demands, allocating mental resources, shifting perspective, and finding balance amongst competing demands56, Avoidance: refers to directing attention away from possibly threatening stimuli and toward stimuli that have the potential to offer safety48,57, Compensation seeking: behaviors to receive financial compensation as a result of an act or injury58 |

| Emotional processes are related to negative affect, emotional (dys)regulation, emotional expression, rejection and intolerance of emotional experiences, acceptance and attendance to emotional experiences, emotional knowledge, emotional contact, or experiencing | Intolerance of uncertainty: a tendency to react negatively on an emotional, cognitive, and behavioral level to uncertain situations59, Anxiety sensitivity: fear of arousal-related bodily sensations, arising from beliefs about the meaning of the sensations. People with high levels of anxiety sensitivity tend to believe that arousal-related bodily sensations are dangerous60, Alexithymia: a cluster of traits characterized by difficulty identifying feelings, describing and identifying emotions, externally oriented thinking, and limited capacity for imaginal thinking61, Neuroticism: a personality trait characterized by a strong tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger. Individuals with this trait have considerable difficulties in coping with stress62 |

PPCS = persistent postconcussion symptoms.

Summary of Transdiagnostic Processes That Have Been Investigated in Concussiona

| Domain . | Transdiagnostic Process Investigated in PPCS . |

|---|---|

| Cognitive processes relate to thought processes, schemas, core beliefs, attention processes, or reasoning processes | Catastrophizing: the tendency to magnify a perceived threat and overestimate the seriousness of its potential consequences50, Illness perceptions: cognitive appraisal and personal understanding of a medical condition and its potential consequences33,51, Expectation as etiology: following an injury, an individual’s anticipation or expectation of specific symptoms might cause them to misattribute future normal, everyday symptoms to the injury, or fail to appreciate the relationship between more proximal factors (eg, life stress, poor sleep, low mood) and their symptoms52, Good-old day bias: the tendency to view oneself as being healthier before the injury and then underestimate historical difficulties53, Perceived injustice: a belief that one has been treated unfairly, disrespectfully and is suffering unnecessarily as a result of another person’s actions54 |

| Behavioral processes compromising behavioral tendencies such as addiction, behavioral avoidance, behaviors caused by emotional arousal (eg, self-harm), reinforcement, behavioral activation | All or nothing behaviors: a behavioral response to symptoms where patients overdo things when they believe symptoms are abating and then spend prolonged periods recovering when symptoms reappear51,55, Psychological flexibility: the pursuit of values despite the presence of pain or distress. It involves adapting to changing situational demands, allocating mental resources, shifting perspective, and finding balance amongst competing demands56, Avoidance: refers to directing attention away from possibly threatening stimuli and toward stimuli that have the potential to offer safety48,57, Compensation seeking: behaviors to receive financial compensation as a result of an act or injury58 |

| Emotional processes are related to negative affect, emotional (dys)regulation, emotional expression, rejection and intolerance of emotional experiences, acceptance and attendance to emotional experiences, emotional knowledge, emotional contact, or experiencing | Intolerance of uncertainty: a tendency to react negatively on an emotional, cognitive, and behavioral level to uncertain situations59, Anxiety sensitivity: fear of arousal-related bodily sensations, arising from beliefs about the meaning of the sensations. People with high levels of anxiety sensitivity tend to believe that arousal-related bodily sensations are dangerous60, Alexithymia: a cluster of traits characterized by difficulty identifying feelings, describing and identifying emotions, externally oriented thinking, and limited capacity for imaginal thinking61, Neuroticism: a personality trait characterized by a strong tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger. Individuals with this trait have considerable difficulties in coping with stress62 |

| Domain . | Transdiagnostic Process Investigated in PPCS . |

|---|---|

| Cognitive processes relate to thought processes, schemas, core beliefs, attention processes, or reasoning processes | Catastrophizing: the tendency to magnify a perceived threat and overestimate the seriousness of its potential consequences50, Illness perceptions: cognitive appraisal and personal understanding of a medical condition and its potential consequences33,51, Expectation as etiology: following an injury, an individual’s anticipation or expectation of specific symptoms might cause them to misattribute future normal, everyday symptoms to the injury, or fail to appreciate the relationship between more proximal factors (eg, life stress, poor sleep, low mood) and their symptoms52, Good-old day bias: the tendency to view oneself as being healthier before the injury and then underestimate historical difficulties53, Perceived injustice: a belief that one has been treated unfairly, disrespectfully and is suffering unnecessarily as a result of another person’s actions54 |

| Behavioral processes compromising behavioral tendencies such as addiction, behavioral avoidance, behaviors caused by emotional arousal (eg, self-harm), reinforcement, behavioral activation | All or nothing behaviors: a behavioral response to symptoms where patients overdo things when they believe symptoms are abating and then spend prolonged periods recovering when symptoms reappear51,55, Psychological flexibility: the pursuit of values despite the presence of pain or distress. It involves adapting to changing situational demands, allocating mental resources, shifting perspective, and finding balance amongst competing demands56, Avoidance: refers to directing attention away from possibly threatening stimuli and toward stimuli that have the potential to offer safety48,57, Compensation seeking: behaviors to receive financial compensation as a result of an act or injury58 |

| Emotional processes are related to negative affect, emotional (dys)regulation, emotional expression, rejection and intolerance of emotional experiences, acceptance and attendance to emotional experiences, emotional knowledge, emotional contact, or experiencing | Intolerance of uncertainty: a tendency to react negatively on an emotional, cognitive, and behavioral level to uncertain situations59, Anxiety sensitivity: fear of arousal-related bodily sensations, arising from beliefs about the meaning of the sensations. People with high levels of anxiety sensitivity tend to believe that arousal-related bodily sensations are dangerous60, Alexithymia: a cluster of traits characterized by difficulty identifying feelings, describing and identifying emotions, externally oriented thinking, and limited capacity for imaginal thinking61, Neuroticism: a personality trait characterized by a strong tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger. Individuals with this trait have considerable difficulties in coping with stress62 |

PPCS = persistent postconcussion symptoms.

| Tenet . | Predictions . | Clinical Application . | Screening Tool Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preinjury psychosocial vulnerabilities | Patients with a preinjury mental health condition are at heightened risk of: • Experiencing more severe acute postconcussion symptoms • Having more heightened psych ological distress following injury • Developing a new mental health condition • Having persistent postconcussion symptoms Preinjury personality traits (neuroticism) and coping styles (passive-avoidance) may also be risk factors for the development of PPCS | Understanding a patient’s preinjury functioning is of the utmost importance This must include the screening of preinjury mental health status, as well as reviewing how the patient has responded to historical stressors. This provides valuable insights into coping styles, resilience, and personality traits Consider referral/engagement in other services to address and manage preinjury mental health difficulties | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Resilience Scale Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale Stressful Life Events Scale Anxiety Sensitivity Index |

| Acute psychological distress | Psychological distress immediately following concussion is common. This can manifest as heightened emotional expression and/or emotional lability This may in part be due to the pathophysiology of concussion, an exacerbation of preinjury status, and/or an acute stress reaction | Screening of a patient’s mental health status immediately after their injury is imperative Educate and normalize emotional symptoms of concussion, as well as the implications of an acute stress reaction Provide strategies to assist with the management of these emotional symptoms (ie, relaxation strategies such as diaphragmatic breathing) | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

| Environmental and contextual factors | The context/environment following injury will have a significant impact on recovery A demanding environment can result in symptom exacerbation, whereas prolonged rest and avoidance produces deconditioning If occurring and context is not modified PPCS will develop over time | View persistent symptoms as developing over time Education and normalization of the fluctuating nature of postconcussion symptoms Acute environmental modifications to support physiological restoration Managing a patient’s response and reaction to a flare-up in symptoms Early education and management are central [to success] | Rivermead Post Concussion Symptom Questionnaire British Columbia Post Concussion Symptom Inventory (BC-PSI) |

| Transdiagnostic processes | Transdiagnostic processes—cognitive, behavioral, and emotional—underlie psychological distress and comorbid difficulties are often present in concussion | Rather than assess broad psychological diagnostic categories (ie, depression and stress) identify the common processes that drive psychological distress These processes are likely to be unique to the individual, their situation, environment, and history Identified processes should be targeted in treatment, ie, graduated exposure to address avoidance that is maintaining anxiety and low mood | Fear Avoidance Behavior in TBI (FAB-TBI) Behavioural Response to Illness Questionnaire (BRIQ) Illness Perception Questionnaire Revised (IPQ-R) Cogniphobia Scale |

| The role of learning principles | Learning principles (operant conditioning, classical conditioning, and generalization) result in transdiagnostic processes being applied rigidly Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive responses can therefore continue over time and maintain psychological distress | Be mindful of generalization and behavioral responses permeating into different environments, contexts, and situations Support the learning of alternative associations to mitigate the impact of generalization | World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) |

| Tenet . | Predictions . | Clinical Application . | Screening Tool Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preinjury psychosocial vulnerabilities | Patients with a preinjury mental health condition are at heightened risk of: • Experiencing more severe acute postconcussion symptoms • Having more heightened psych ological distress following injury • Developing a new mental health condition • Having persistent postconcussion symptoms Preinjury personality traits (neuroticism) and coping styles (passive-avoidance) may also be risk factors for the development of PPCS | Understanding a patient’s preinjury functioning is of the utmost importance This must include the screening of preinjury mental health status, as well as reviewing how the patient has responded to historical stressors. This provides valuable insights into coping styles, resilience, and personality traits Consider referral/engagement in other services to address and manage preinjury mental health difficulties | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Resilience Scale Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale Stressful Life Events Scale Anxiety Sensitivity Index |

| Acute psychological distress | Psychological distress immediately following concussion is common. This can manifest as heightened emotional expression and/or emotional lability This may in part be due to the pathophysiology of concussion, an exacerbation of preinjury status, and/or an acute stress reaction | Screening of a patient’s mental health status immediately after their injury is imperative Educate and normalize emotional symptoms of concussion, as well as the implications of an acute stress reaction Provide strategies to assist with the management of these emotional symptoms (ie, relaxation strategies such as diaphragmatic breathing) | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

| Environmental and contextual factors | The context/environment following injury will have a significant impact on recovery A demanding environment can result in symptom exacerbation, whereas prolonged rest and avoidance produces deconditioning If occurring and context is not modified PPCS will develop over time | View persistent symptoms as developing over time Education and normalization of the fluctuating nature of postconcussion symptoms Acute environmental modifications to support physiological restoration Managing a patient’s response and reaction to a flare-up in symptoms Early education and management are central [to success] | Rivermead Post Concussion Symptom Questionnaire British Columbia Post Concussion Symptom Inventory (BC-PSI) |

| Transdiagnostic processes | Transdiagnostic processes—cognitive, behavioral, and emotional—underlie psychological distress and comorbid difficulties are often present in concussion | Rather than assess broad psychological diagnostic categories (ie, depression and stress) identify the common processes that drive psychological distress These processes are likely to be unique to the individual, their situation, environment, and history Identified processes should be targeted in treatment, ie, graduated exposure to address avoidance that is maintaining anxiety and low mood | Fear Avoidance Behavior in TBI (FAB-TBI) Behavioural Response to Illness Questionnaire (BRIQ) Illness Perception Questionnaire Revised (IPQ-R) Cogniphobia Scale |

| The role of learning principles | Learning principles (operant conditioning, classical conditioning, and generalization) result in transdiagnostic processes being applied rigidly Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive responses can therefore continue over time and maintain psychological distress | Be mindful of generalization and behavioral responses permeating into different environments, contexts, and situations Support the learning of alternative associations to mitigate the impact of generalization | World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) |

PPCS = persistent postconcussion symptoms; TBI = traumatic brain injury.

| Tenet . | Predictions . | Clinical Application . | Screening Tool Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preinjury psychosocial vulnerabilities | Patients with a preinjury mental health condition are at heightened risk of: • Experiencing more severe acute postconcussion symptoms • Having more heightened psych ological distress following injury • Developing a new mental health condition • Having persistent postconcussion symptoms Preinjury personality traits (neuroticism) and coping styles (passive-avoidance) may also be risk factors for the development of PPCS | Understanding a patient’s preinjury functioning is of the utmost importance This must include the screening of preinjury mental health status, as well as reviewing how the patient has responded to historical stressors. This provides valuable insights into coping styles, resilience, and personality traits Consider referral/engagement in other services to address and manage preinjury mental health difficulties | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Resilience Scale Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale Stressful Life Events Scale Anxiety Sensitivity Index |

| Acute psychological distress | Psychological distress immediately following concussion is common. This can manifest as heightened emotional expression and/or emotional lability This may in part be due to the pathophysiology of concussion, an exacerbation of preinjury status, and/or an acute stress reaction | Screening of a patient’s mental health status immediately after their injury is imperative Educate and normalize emotional symptoms of concussion, as well as the implications of an acute stress reaction Provide strategies to assist with the management of these emotional symptoms (ie, relaxation strategies such as diaphragmatic breathing) | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

| Environmental and contextual factors | The context/environment following injury will have a significant impact on recovery A demanding environment can result in symptom exacerbation, whereas prolonged rest and avoidance produces deconditioning If occurring and context is not modified PPCS will develop over time | View persistent symptoms as developing over time Education and normalization of the fluctuating nature of postconcussion symptoms Acute environmental modifications to support physiological restoration Managing a patient’s response and reaction to a flare-up in symptoms Early education and management are central [to success] | Rivermead Post Concussion Symptom Questionnaire British Columbia Post Concussion Symptom Inventory (BC-PSI) |

| Transdiagnostic processes | Transdiagnostic processes—cognitive, behavioral, and emotional—underlie psychological distress and comorbid difficulties are often present in concussion | Rather than assess broad psychological diagnostic categories (ie, depression and stress) identify the common processes that drive psychological distress These processes are likely to be unique to the individual, their situation, environment, and history Identified processes should be targeted in treatment, ie, graduated exposure to address avoidance that is maintaining anxiety and low mood | Fear Avoidance Behavior in TBI (FAB-TBI) Behavioural Response to Illness Questionnaire (BRIQ) Illness Perception Questionnaire Revised (IPQ-R) Cogniphobia Scale |

| The role of learning principles | Learning principles (operant conditioning, classical conditioning, and generalization) result in transdiagnostic processes being applied rigidly Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive responses can therefore continue over time and maintain psychological distress | Be mindful of generalization and behavioral responses permeating into different environments, contexts, and situations Support the learning of alternative associations to mitigate the impact of generalization | World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) |

| Tenet . | Predictions . | Clinical Application . | Screening Tool Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preinjury psychosocial vulnerabilities | Patients with a preinjury mental health condition are at heightened risk of: • Experiencing more severe acute postconcussion symptoms • Having more heightened psych ological distress following injury • Developing a new mental health condition • Having persistent postconcussion symptoms Preinjury personality traits (neuroticism) and coping styles (passive-avoidance) may also be risk factors for the development of PPCS | Understanding a patient’s preinjury functioning is of the utmost importance This must include the screening of preinjury mental health status, as well as reviewing how the patient has responded to historical stressors. This provides valuable insights into coping styles, resilience, and personality traits Consider referral/engagement in other services to address and manage preinjury mental health difficulties | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Resilience Scale Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale Stressful Life Events Scale Anxiety Sensitivity Index |

| Acute psychological distress | Psychological distress immediately following concussion is common. This can manifest as heightened emotional expression and/or emotional lability This may in part be due to the pathophysiology of concussion, an exacerbation of preinjury status, and/or an acute stress reaction | Screening of a patient’s mental health status immediately after their injury is imperative Educate and normalize emotional symptoms of concussion, as well as the implications of an acute stress reaction Provide strategies to assist with the management of these emotional symptoms (ie, relaxation strategies such as diaphragmatic breathing) | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

| Environmental and contextual factors | The context/environment following injury will have a significant impact on recovery A demanding environment can result in symptom exacerbation, whereas prolonged rest and avoidance produces deconditioning If occurring and context is not modified PPCS will develop over time | View persistent symptoms as developing over time Education and normalization of the fluctuating nature of postconcussion symptoms Acute environmental modifications to support physiological restoration Managing a patient’s response and reaction to a flare-up in symptoms Early education and management are central [to success] | Rivermead Post Concussion Symptom Questionnaire British Columbia Post Concussion Symptom Inventory (BC-PSI) |

| Transdiagnostic processes | Transdiagnostic processes—cognitive, behavioral, and emotional—underlie psychological distress and comorbid difficulties are often present in concussion | Rather than assess broad psychological diagnostic categories (ie, depression and stress) identify the common processes that drive psychological distress These processes are likely to be unique to the individual, their situation, environment, and history Identified processes should be targeted in treatment, ie, graduated exposure to address avoidance that is maintaining anxiety and low mood | Fear Avoidance Behavior in TBI (FAB-TBI) Behavioural Response to Illness Questionnaire (BRIQ) Illness Perception Questionnaire Revised (IPQ-R) Cogniphobia Scale |

| The role of learning principles | Learning principles (operant conditioning, classical conditioning, and generalization) result in transdiagnostic processes being applied rigidly Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive responses can therefore continue over time and maintain psychological distress | Be mindful of generalization and behavioral responses permeating into different environments, contexts, and situations Support the learning of alternative associations to mitigate the impact of generalization | World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) |

PPCS = persistent postconcussion symptoms; TBI = traumatic brain injury.

Ella and Jessica have transdiagnostic processes evident in their presentations (ie, avoidance, illness perception, all-or-nothing behavior). However, in Ella’s case, these processes were often not conducive to recovery and transpired over time to maintain and exacerbate psychological distress. For example, Ella’s all-or-nothing behavior precipitated a pattern of overactivity that impacted symptom recovery. Despite being provided with education, the pervasive nature of Ella’s symptoms resulted in perceptions and misattributions being made that something was seriously wrong. These transdiagnostic processes then drove further stress and anxiety. Furthermore, Ella’s all-or-nothing behavioral tendency played out further when she had time off work and a gradual return to activities was advised. Again, despite education, Ella avoided engaging in activities, and catastrophizing cognitions pertaining to the severity of her symptoms were very much evident. Thus, Ella did not have opportunities to habituate to her symptoms through graduated exposure to activities. When she returned to work for a second time, again the demands placed on her exceeded her capacity to cope and manage, further reinforcing and driving (see Tenet 5) these transdiagnostic processes.

Tenet 5: The Role of Learning Principles

Experiences before and during recovery are shaped by learning principles, which influence how transdiagnostic processes are applied. Transdiagnostic processes are not inherently maladaptive, and in certain contexts following certain experiences, can be conducive to recovery.63 For example, early avoidance of strenuous activity is important, as evident in Jessica’s case. However, as in Ella’s case, if avoidance persists, symptoms can be maintained.64 Learning principles reinforce behavioral responses and result in transdiagnostic processes being applied rigidly despite changes in context.52 This then maintains and exacerbates psychological distress over time.

Postconcussion symptoms can be potent stimuli in learning due to their aversive nature. This is particularly salient in environmental contexts where symptoms are intensified (see Tenet 3). When this occurs, 3 prominent learning principles reinforce behavior.52 First, in classical conditioning, people learn to predict the onset of potentially harmful stimuli.65 A neutral stimulus (reading a book; conditioned stimulus) is followed by an aversive stimulus (headache; unconditioned stimulus) resulting in an unconditioned response (ie, fear, worry, distress). Because reading a book (conditioned stimulus) becomes a predictor of a headache (unconditioned stimulus), seeing a book can elicit the unconditioned response—fear, worry, and distress. If reinforced, this association is stored in memory for future use and cannot simply be erased.66 Interestingly, just thinking about reading a book can now activate the memory of the headache and thereby generate fear.67 In Ella’s case, classical conditioning resulted in an association being created between work and psychological distress (fear, anxiety, worry). Consequently, the prospect of returning to work elicited the same emotional response (fear, anxiety, worry).

Second, in operant conditioning, people learn about the association between behavior and its consequence in each situation.52 Behavior changes because of this consequence. For example, an experience (reading a book results in a headache) causes a behavioral response (stop reading). A favorable outcome ensues as the headache reduces. An association develops between the consequences of a behavior in response to a stimulus (avoiding reading will prevent headaches).68 This type of learning is important in PPCS, because people with postconcussion symptoms may develop new behavioral routines (ie, resting, limiting functioning, avoiding certain tasks) that may be reinforced in different environments (ie, avoid reading a book at home ➔ avoid reading a work email).69 Postconcussion symptoms can be powerful stimuli given their fluctuating nature (see Tenet 3). When this occurs, the association between stimuli and responses/behaviors is strengthened through the development of these learning principles.52,70 Hence, reinforcement may not be continuous and can occur intermittently. It reduces the ability to foresee a consistent consequence, and hence a person’s response is strengthened because they will engage in a behavior even if the expected outcome does not occur. In Ella’s case, she experienced events with high emotional salience that strengthened the association between the response and the environment. Once a behavior is learned, it may be maintained with surprisingly little reinforcement and can persist over time.70

Finally, generalization occurs when knowledge from one situation is extrapolated to another without having experienced that other situation.71 This is an important feature of learning theory because people do not have to learn all possible associations one by one. However, it can result in an adaptive response becoming maladaptive as it permeates into other contexts.72 This was evident in Ella’s case where her initial avoidance of leisure tasks generalized to activities associated with work resulting in a significant reduction in functioning. Certain transdiagnostic processes, such as avoidance, have a notorious propensity to generalize.73 For example, there is little opportunity to extinguish avoidant behavior because the consequence that would have occurred by not avoiding never happened. Ella was not able to learn that doing light leisure activities (ie, gardening) at home did not cause a headache because this new association (gardening ➔ no headache) was never created.

In summary, these 5 tenets provide an explanatory account of how psychological variables contribute to the development of PPCS within biopsychosocial conceptualizations. The Figure illustrates the interrelated nature of the tenets with reference to the facets of concussion recovery. Specifically, it demonstrates the contribution that each tenet likely makes to the development of psychological distress over the course of concussion recovery and its consequence on functional outcomes. The aforementioned Figure is adapted from Rickards et al14; however, instead of illustrating the broad facets of concussion recovery and their role in PPCS development, the adapted Figure has a more specific focus on the psychological factors that contribute to PPCS.

Applying the Tenets in Clinical Practice

Traditionally, the clinical management of concussion involved minimal input beyond watchful waiting.74 However, in response to mounting evidence on the chronicity and severity of PPCS, numerous expert agreement and clinical practice guidelines have been published.16 In very general terms, these guidelines emphasize the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. Clinical diagnosis (presentation, rule outs, and comorbidities) and early clinical management are essential. This includes education (ie, what a concussion is, expectations of recovery, and advice on symptom management) and return to activity advice. Specifically, it is recommended that after a period of relative rest for the first 24 to 48 hours, patients should gradually resume normal daily activities as tolerated.75 These practice guidelines are well supported, and in Jessica’s case, when applied, can result in successful outcomes. However, psychological factors also need to be considered and as a result, irrespective of professional discipline, treatment guidelines also stipulate the importance of assessing and addressing psychological factors.15,16 This is essential in cases like Ella’s. Ella and Jessica had very different recovery journeys despite experiencing similar injuries and receiving specialist concussion treatment. It is evident that psychological factors had an impact on Ella’s recovery, and if they had been identified and treated earlier the development of PPCS may have been mitigated. It must, however, be acknowledged that in accordance with biopsychosocial models there may also be other factors that contributed to Ella’s PPCS that would need to be assessed and treated. The 5 interrelated tenets do not negate the importance and influence of these factors. Instead, they focus on the psychological factors within biopsychosocial explanatory models and provide guidance from an empirically derived framework that can be applied to support concussion recovery.

Addressing psychological factors in rehabilitation can take several different forms from identification of psychological risk, assessment of current mental health status, education, the implementation of strategies to manage psychological symptoms, and, when indicated, referral for specialized mental health treatment. The 5 interrelated tenets provide guidance to support all clinicians in this process. They give clarity by providing a rich individualistic understanding of the role of psychological factors in concussion recovery. Specifically, clinical hypotheses can be derived from the tenets, which can be tested by clinicians. Table 2 provides examples of these predictions, their application in clinical practice, and tools that can be used to assist this process. Many of these suggestions are not new, but we assert that these can be derived from the 5 tenets in an accessible framework that all rehabilitation clinicians can implement.

More specifically, the 5 interrelated tenets first emphasize the importance of identifying preinjury psychosocial risk (Tenet 1). This is particularly pertinent in cases like Ella’s, where the identification of preinjury psychological risk factors would have ensured additional strategies were put in place to mitigate their contribution to persistent symptoms. An awareness of Ella’s preinjury stressors and their implication on her work environment would have ensured that early in her recovery additional support was put in place to address these. This was not needed in Jessica’s case. Second, the tenets also emphasize the importance of assessing acute distress (Tenet 2) given the unique pathophysiology of a concussion and its impact on emotional intensity and lability. When applied in clinical practice, this guides clinicians to include this in the education they provide and to normalize this response to mitigate uncertainty and confusion. This is essential in cases like Ella’s where preinjury psychosocial risk can increase the severity of acute distress. The introduction of mental health management techniques or a referral for specialist mental health care to support the management of these symptoms can then be implemented. If this does not occur, these psychological symptoms can increase over time. Third, the 5 interrelated tenets also guide clinicians to explore and address the role that environment and context (Tenet 3) have on concussion recovery and psychological status. This tenet guides clinicians to educate patients that symptom fluctuation is likely to occur in certain environmental contexts. Furthermore, appreciation of the unique environmental precipitants of mental distress and symptom increase can ensure that treatment is tailored with this context front and center. The potential future impact of environmental and contextual factors on recovery can then be mitigated. In Ella’s case, work, the environment, the relationships within it, and the tasks required, were all salient drivers of her mental health difficulties. Thus, Ella could be supported to become attuned to triggers within this context (ie, worry regarding how she is perceived at work) and then practice strategies that can be implemented based on these (ie. reframing); these context-specific strategies can then be practiced in vivo with all the treating clinicians. If this had occurred, Ella would have been equipped with strategies to help manage her activity. We argue that a generic approach to mental health management without awareness of context is unlikely to be optimal. Finally, the proposed framework guides clinicians to go further and tease out the specific psychological processes (Tenet 4) that drive mental distress; it also explains why these processes might persist over time (Tenet 5). This can improve the effectiveness of treatment because the specific psychological process can then be addressed. For example, for Ella, the use of graded exposure and cognitive restructuring techniques may be helpful in challenging her all-or-nothing behavior, avoidance, and cognitions.76 When these transdiagnostic processes are reinforced and applied consistently through learning principles, referral to specialist mental health treatment is likely to be indicated. In this instance, the introduction of evidence-based psychological therapy (ie, cognitive behavioral therapy) interventions is likely to be warranted.

Conclusions

The development of PPCS from a psychological perspective can be explained by 5 interrelated tenets: preinjury psychosocial vulnerabilities, acute psychological distress, environment and contextual factors, transdiagnostic processes, and learning principles. These tenets can be used to enhance current understanding of the etiology of PPCS from a psychological perspective within current biopsychosocial models. They provide all clinicians involved in concussion rehabilitation with a framework to explain why, from a psychological perspective, PPCS may develop in one person (Ella), but not in another (Jessica). We by no means view this model as complete, and acknowledge that from a biopsychosocial perspective there are still mysteries to be solved. To support this ongoing endeavor, our tenets provide a platform to launch further investigations into PPCS with iterations and reviews likely needed as new evidence emerges. However, at present, we hope that the 5 tenets can be used by clinicians to support the mitigation and management of PPCS.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: J.W. Faulkner, D.L. Snell

Writing: J.W. Faulkner, D.L. Snell

Project management: J.W. Faulkner

Fund procurement: J.W. Faulkner, D.L. Snell

Providing facilities/equipment: J.W. Faulkner

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): D.L. Snell

Funding

This study was funded by a Health Research Council of New Zealand Foxley Clinical Fellowship (20/041). The funder played no role in the writing of this work.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

Comments