-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Chelsea R Chapman, Nathan T Woo, Katrina S Maluf, Preferred Communication Strategies Used by Physical Therapists in Chronic Pain Rehabilitation: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis, Physical Therapy, Volume 102, Issue 9, September 2022, pzac081, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac081

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Lack of clarity regarding effective communication behaviors in chronic pain management is a barrier for implementing psychologically informed physical therapy approaches that rely on competent communication by physical therapist providers. This study aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-synthesis to inform the development of a conceptual framework for preferred communication behaviors in pain rehabilitation.

Ten databases in the health and communication sciences were systematically searched for qualitative and mixed-method studies of interpersonal communication between physical therapists and adults with chronic pain. Two independent investigators extracted quotations with implicit and explicit references to communication and study characteristics following Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. Methodological quality for individual studies was assessed with Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, and quality of evidence was evaluated with GRADE-CERQual. An inductive thematic synthesis was conducted by coding each quotation, developing descriptive themes, and then generating behaviorally distinct analytical themes.

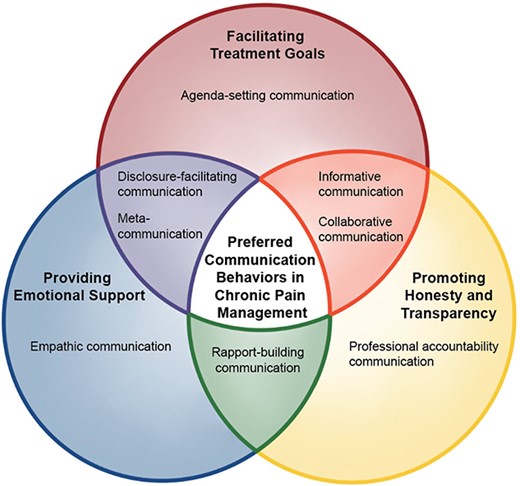

Eleven studies involving 346 participants were included. The specificity of operationalizing communication terms varied widely. Meta-synthesis identified 8 communication themes: (1) disclosure-facilitating, (2) rapport-building, (3) empathic, (4) collaborative, (5) professional accountability, (6) informative, (7) agenda-setting, and (8) meta-communication. Based on the quality of available evidence, confidence was moderate for 4 themes and low for 4 themes.

This study revealed limited operationalization of communication behaviors preferred by physical therapists in chronic pain rehabilitation. A conceptual framework based on 8 communication themes identified from the literature is proposed as a preliminary paradigm to guide future research.

This proposed evidence-based conceptual framework for preferred communication behaviors in pain rehabilitation provides a framework for clinicians to reflect on their own communication practices and will allow researchers to identify if and how specific communication behaviors impact clinical outcomes.

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic pain worldwide is 30.3%,1 being one of the most common reasons adults seek medical care.2 Chronic pain often presents with anxious or depressed mood3–5 and is associated with greater disability5 and reduced quality of life.6 Adverse health outcomes resulting from iatrogenic opioid dependence are also higher among individuals with chronic pain.4,7,8 Pain impacts the general population to the extent that international law recognizes pain management as a basic human right.9 The Institute of Medicine recognizes physical therapy as an effective nonpharmacological approach to treating chronic pain.10

Physical therapists evaluate and treat patients with chronic pain stemming from a variety of health conditions and have advocated for the adoption of psychologically informed physical therapy (PIPT) in chronic pain management.11 PIPT combines traditional biomedical physical therapy interventions (eg, therapeutic exercise, physical modalities, manual therapies) with 1 or more behavioral elements adapted from evidence-based psychotherapies for pain management (eg, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy,12–14 Acceptance and Commitment Therapy,13 Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction).14 Despite evidence that chronic pain is impacted by the cognitive, emotional, social, and contextual factors targeted by PIPT, this approach has shown only small to moderate effects on pain and disability when implemented by physical therapists.15,16 We postulate that lack of confidence in managing psychosocial aspects of care through therapeutic pain communication may be 1 of several factors contributing to the limited impact of PIPT in clinical practice. The ability of physical therapists to recognize and implement effective communication skills is a key component of PIPT,17 yet lack of confidence in communication skills has been cited as a reason for physical therapists not implementing PIPT approaches in chronic pain rehabilitation despite recognition of their value.18,19 Regardless of the therapeutic approach, patient-provider communication is a critical factor in fostering therapeutic alliance, which has been shown to improve pain outcomes in rehabilitation settings.20

Communication is ubiquitious, because one “cannot not communicate,” 21 but competent communication22,23 is more rare. Communication competence is formally defined as “the degree to which meaningful behavior is perceived as appropriate and effective in a given context”; this judgement is influenced by a combination of the communicator’s motivation, knowledge, and skills.22,23 Competent communication effectively and appropriately conveys meaning and has been linked to more accurate patient reporting and disclosure, better treatment adherence, and improved clinical outcomes in a variety of health care settings.24–26 Several entry-level and postprofessional training programs have recently been developed to advance physical therapists’ competency in therapeutic pain communication.17,27 We propose that lack of clarity regarding what behaviors constitute competent communication in the field of pain rehabilitation presents a major barrier for such training initiatives.

The primary aims of this study were to (1) conduct a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies describing communication behaviors utilized by physical therapists when treating adults with chronic pain, and (2) develop a conceptual framework to operationalize preferred communication behaviors in pain rehabilitation based on findings from the meta-synthesis. A secondary aim was to identify intermediary and terminal variables linking preferred communication behaviors with patient outcomes. We define communication behaviors as the act of using verbal or nonverbal means to convey meaning to another. In the absence of direct evidence supporting the clinical efficacy of specific communication behaviors, we use preferred communication as an umbrella term encompassing the varied terminology used for behaviors with implied benefit in patient-provider interactions (eg, competent, effective, good, skilled, meaningful, etc).

Methods

This review was registered in International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42020166258) and follows reporting guidelines from the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research statement.28 Consistent with prior reviews in the field of pain rehabilitation,11,29 we conducted a meta-synthesis following procedures recommended by Sandelowski, Barroso, and Voils30 because this method is particularly suited for synthesis of data from qualitative studies using varied methodologies.31 After a systematic search of the literature, meta-synthesis of included studies was conducted in 3 stages: (1) relevant findings were extracted, (2) data were grouped based on topical similarity using thematic synthesis, and (3) findings were abstracted and formatted to eliminate redundancies while preserving the complexity of their content. In lieu of frequency effect sizes,30 a sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the contribution of included studies to the final set of abstracted communication themes. Each stage of the systematic review and meta-synthesis is further detailed below.

Data Sources and Searches

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, SPORTDiscus, Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (ProQuest), ComDisDome, PsycARTICLES, and Communication and Mass Media Complete. Variations of 4 primary search term criteria were used to identify relevant studies: (1) chronic pain, (2) physical therapy, (3) communication, and (4) qualitative research. A preliminary search of the literature was completed in December 2019 to pilot the study procedures. The full search was conducted from January to March 2020, and a final search was conducted on June 22, 2021, to identify any recently published studies for inclusion prior to publication. Databases were searched from inception through the final search date. The search strategy (Suppl. Appendix 1) was developed with assistance from a medical librarian. References were exported to Endnote (Version X9; Thomas Reuters, New York, NY, USA), duplicates were removed, and titles and abstracts were independently screened by 2 investigators (C.C. and N.W.). Full-text articles were obtained for potentially eligible studies and were independently reviewed by the same 2 investigators using predetermined eligibility criteria. In cases of disagreement, a third investigator (K.M.) facilitated consensus regarding the selection of included studies.

Study Selection

Participants

Studies involving adult patients undergoing physical therapy management of chronic pain were included. Chronic pain was defined as persistent or recurring pain anywhere in the body lasting 3 or more months.32 Provider groups in these studies could be exclusively or partially comprised of physical therapists. Only settings in which physical therapy services were delivered face-to-face were included; studies using telehealth or other electronic platforms to deliver physical therapy services were excluded.

Exposure and Study Design

We included qualitative and mixed methods studies exploring interpersonal communication used by physical therapists in interactions with adult patients treated for chronic pain. We excluded studies that focused exclusively on patient communication or communication between providers rather than between patient and provider. We also excluded studies with exclusively quantitative designs and any study not published in English.

Communication Behaviors

We were primarily interested in extracting communication behaviors used by physical therapists during the rehabilitation of individuals with chronic pain. Communication behavior could be referenced explicitly (eg, “open communication channels with the patients”) or implicitly (eg, “the amount of support I give them in saying, ‘I’m gonna help you’ makes them believe they can get better”)33 by investigators, physical therapists, or their patients. Additionally, we extracted any intermediary or terminal variable linked with communication behaviors in the primary review and potentially important for patient outcomes, including but not limited to self-efficacy, therapeutic alliance, pain intensity, and pain interference. An additional targeted search was performed to extract quotations with an explicit or implicit reference to nonverbal forms of communication due to their unexpectedly limited representation in the initial round of extracted communication behaviors.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data Extraction

Two investigators (C.C. and N.W.) independently extracted study characteristics and physical therapist communication behaviors from eligible studies into separate spreadsheets using a custom template, with a third investigator (K.M.) available to discuss and resolve any discrepancies. The template was developed using selected items from Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)34 to detail participant and setting characteristics, combined with the 21-item Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist to describe study aims, methodology, evidence, and main findings. Communication quotations from investigators, physical therapists, and patients were extracted with the provision that the communication referenced was identified as the physical therapist’s (eg, physical therapist reflecting on their own communication, or patients reflecting on their physical therapist’s communication).

Quality Assessment

Two investigators (C.C. and N.W.) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP).35 Discrepancies were resolved by a third investigator (K.M.). This tool has been extensively used in qualitative systematic reviews of rehabilitation research because it allows raters to identify a range of limitations that can affect conclusions made by qualitative studies using various methodologies.29,36,37 The same investigators performed an independent sensitivity analysis of studies contributing to each theme and assessed the quality of the evidence using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual).38,39 GRADE-CERQual critiques 4 areas for each theme: (1) methodological limitations (determined by CASP criteria), (2) adequacy of data, (3) coherence, and (4) relevance. The quality of evidence appraisal was performed to promote transparency of findings and to determine how much confidence to place in each theme.

Data Grouping and Abstraction: Thematic Synthesis

A thematic synthesis was conducted using methods proposed by Thomas and Harden.40 This method was chosen because it preserves the context that is integral to qualitative inquiry while providing succinct thematic results; anyone can follow the path of descriptive and analytic themes to form their own judgements because themes are provided alongside raw data quotes and contextual elements. Three stages of analysis included (1) coding text in a targeted line-by-line fashion, (2) developing descriptive subthemes from the initial coding, and (3) generating analytical themes from the descriptive subthemes. This process is inductive in that the analysis starts at the micro level of each line of text and then broadens as subthemes and themes are discovered iteratively. Quotations were extracted that contained description or identification of communication behaviors used by physical therapists in chronic pain rehabilitation. We included primary data with verbatim quotations for all themes to enhance trustworthiness and transparency. Lines were analyzed if each investigator (C.C. and N.W.) independently identified that a communication behavior was used by a physical therapist, regardless of whether the speaker was a physical therapist or patient. Quotations were included if communication was mentioned explicitly or discussed implicitly (eg, “admit your limitations” and “ask for help” are examples of implicitly referenced communication).41 Thematic synthesis is a method of data abstraction that identifies and develops an explicit link between lines of text analyzed and the conclusions presented. Subthemes and themes were analyzed and compared by the investigators to ensure agreement on quotation selection and theme assignment. Redundancies were removed by consolidating similar or overlapping subthemes, and the remaining subthemes were grouped into descriptive themes for preferred communication in pain rehabilitation. Results were formatted in a table to illustrate the topical similarity and thematic diversity of summarized findings. Any disagreements between investigators during the process of thematic synthesis were resolved through discussion and consensus of all authors.

Role of the Funding Source

The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Study Identification and Selection

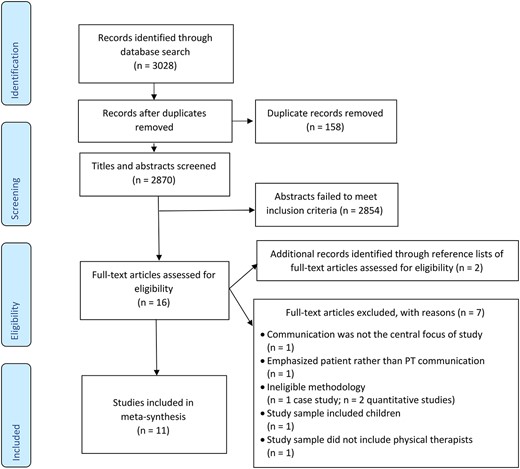

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1) details the process of study selection. We identified 3028 articles from 4 of the 10 databases searched. After removing 158 duplicates,42 we screened titles and abstracts for 2870 studies, removing an additional 2854. Sixteen studies were included for full-text screening, and 2 additional articles were found by searching the reference lists of full-text articles. Eleven studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-synthesis.33,41,43–51

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for study inclusion.

Characteristics of Included Studies

The 11 included studies were published between 1998 and 2019. Most studies were conducted in Western countries.33,41,43–49,51 The studies involved 346 physical therapist and patient participants representing a variety of chronic pain conditions and treatment settings. Conditions ranged from generalized chronic or persistent pain without serious causative or contributory disease to localized musculoskeletal pain in the low back and/or neck, with 1 study of posttraumatic paraplegia chronic pain. Settings included primary care hospitals, outpatient rehabilitation centers, sports medicine clinics, private practices, and home health services. Data collection and analysis techniques also varied across studies. Seven studies used structured or semistructured interviews,33,44,45,47,49–51 2 used focus groups,43,46 and 3 were observational41,47,48 (1 of these also used interviews).47 A detailed summary of study characteristics is presented in Table 1.

| Study Aim(s) . | No., PT: Patient . | PT Sex, M:F . | PT Age: Years of Clinical Experienceb . | Patient Sex, M:F . | Patient Age, yb . | Pain Condition: Treatment Setting . | Country . | Sampling Procedurec . | Data Collection Method(s) . | Data Analysis Method(s) . | Communication Operationalization . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To find out how PTs experienced influence of systematically prepared key questioning on their relation to and understanding of patients with long-standing pain Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | 6:80 | NR | 39–62: 10–25 | Majority female | 18–70 | Chronic pain without serious causative or contributory disease: pain rehabilitation clinics, primary care, Feldenkrais private practice | Sweden | Convenience | Focus group interviews | Phenomenography | A priori operationalization: “By communication method for the encounter between physiotherapist and patient we mean a method which combines an ethical attitude with conscious speech acts and sensitivity to the patient’s body experience” |

| (1) To determine factors that affected PTs’ perception of patients’ pain and (2) determine how this perception affected patient management Askew et al,33 1998 | 46:0 | 19:27 | 25–48: 2–25 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: pain management outpatient orthopedic and sports medicine clinics | USA | Convenience | Structured interviews | Coded, included quotes from interviews for thematic categories | No explicit operationalization |

| To define patient-centeredness from patient’s perspective in context of physical therapy for CLBP Cooper et al,44 2008 | 0:25 | NR | NR | 5:20 | 18–65 | CLBP: Physiotherapy Department of National Health Service | Scotland | Purposive sampling based on location of physical therapy practice (urban or rural), gender, age, and management style (group, one-to-one, or mixed) | Semistructured interviews | Framework analysis—data management, descriptive analysis, and explanatory analysis | Post hoc operationalization: via interviewing physical therapists “Good communication involved: taking time over explanations; using appropriate terminology; and encouraging the patient’s participation in the communication process” |

| To contribute to wider evidence base as to how PTs understand and deal with non-specific CLBP disorders from BPS perspective, and perceived barriers to provision of BPS model of care delivery in primary care setting Cowell et al,45 2018 | 10:0 | 7:3 | 18–70: 4–14+ | NR | NR | Nonspecific CLBP: primary care | England | Purposive sampling based on sex, age, and clinical experience | Semistructured face-to-face qualitative interviews | Thematic analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To identify elements of PT–patient interaction considered by patients when they evaluate quality of care in outpatient rehabilitation settings Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | 0:57 | NR | NR | 33:24 | 18+ | Chronic musculoskeletal pain: post-acute outpatient rehabilitation clinic | Spain | Purposive sampling based on age, gender, and clinical condition | Audiotaped focus group interviews | Thematic analysis using modified grounded theory approach | No explicit operationalization |

| To investigate how many and what verbally expressed emotions PTs state during interviews between PTs and patients Gard et al,41 2000 | 10:0 | 0:10 | 44–62: 7–41 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: clinical health tutors in primary health care, tutoring physical therapy | Sweden | Purposive sampling based on clinical specialties | Qualitative case series | Cross-case analysis | A priori operationalization: categorization of emotions by Tomkins65,66 (1962, 1984) and Izard67 (1977) |

| To describe communicative patterns about change in demanding physical therapy treatment situations Øien et al,47 2011 | 6:11 | 1:5 | 44–68: 20–47 | 1:10 | 22–47 | Chronic muscular pain located in back and/or neck: outpatient clinic | Norway | Convenience | Interviews, patients’ notes, videorecorded treatment sessions, and researchers’ field notes | Løvlie – Schibbye’s part process analysis | A priori operationalization based on System Theory of Communication: “The theme is often verbally communicated. The meta-communication encompasses nonverbal emotional expressions related to the theme. The theme the meta-communication structure define the relationship… Communication is based on the observable manifestations of the relationship. All behavior—including speech, tone of voice, silence, withdrawal, immobility or denial—is communication.” |

| To explore how French-speaking PTs and patients with LBP explore and assess patient’s pain experience during initial encounters Opsommer and Schoeb,48 2014 | 2:6 | NR | NR: 0–20 | 4:2 | 18+ | CLBP: university hospital and private practice | Switzerland | Convenience | Videotaped initial encounters | Conversation analysis | Post hoc operationalization via conversation analytic components |

| To investigate prevalence of long-term treatment and identify and classify reasons why PT clinicians continue to treat LBP patients in absence of objective improvement Pincus et al,49 2006 | 21:0 for interviews; 354:0 for surveys | NR (interviews); 71:283 (surveys) | NR for interviews; 20–60+ for surveys: mean 12.8 (SD NR) for interviews; NR for surveys | NR | NR | CLBP: National Health Service primary and secondary care, or private practice | England | Combination of stratified and purposive sampling based on age, gender, and private/public practice setting | Interviews and surveys | Mixed methods: grounded theory analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To explore PTs’ perspectives about patients with incomplete posttraumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home exercises Serpanou et al,50 2019 | 13:0 | 7:6 | 30–47: 5–22 | NR | NR | Posttraumatic paraplegia: home health services | Greece | Convenience | Semistructured interviews | Qualitative content analysis | Post hoc operationalization from interviewing PTs: “All participants agree that good communication with the patient helps in overcoming obstacles. Communication is a 2-way process between the physical therapist and the patient, and it is necessary in order to understand each other’s problems and expectations.” |

| To answer research question: “What are PTs’ perspectives on managing the cognitive, psychological, and social dimensions of CLBP after intensive biopsychosocial training?” Synnott et al,51 2016 | 13:0 | 9:4 | 30–47: mean 13 (SD = 3.8) | NR | NR | CLBP: NR | Belgium, Australia, Denmark, Ireland | Purposive | Audiotaped interviews | Interpretive descriptive analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| Study Aim(s) . | No., PT: Patient . | PT Sex, M:F . | PT Age: Years of Clinical Experienceb . | Patient Sex, M:F . | Patient Age, yb . | Pain Condition: Treatment Setting . | Country . | Sampling Procedurec . | Data Collection Method(s) . | Data Analysis Method(s) . | Communication Operationalization . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To find out how PTs experienced influence of systematically prepared key questioning on their relation to and understanding of patients with long-standing pain Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | 6:80 | NR | 39–62: 10–25 | Majority female | 18–70 | Chronic pain without serious causative or contributory disease: pain rehabilitation clinics, primary care, Feldenkrais private practice | Sweden | Convenience | Focus group interviews | Phenomenography | A priori operationalization: “By communication method for the encounter between physiotherapist and patient we mean a method which combines an ethical attitude with conscious speech acts and sensitivity to the patient’s body experience” |

| (1) To determine factors that affected PTs’ perception of patients’ pain and (2) determine how this perception affected patient management Askew et al,33 1998 | 46:0 | 19:27 | 25–48: 2–25 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: pain management outpatient orthopedic and sports medicine clinics | USA | Convenience | Structured interviews | Coded, included quotes from interviews for thematic categories | No explicit operationalization |

| To define patient-centeredness from patient’s perspective in context of physical therapy for CLBP Cooper et al,44 2008 | 0:25 | NR | NR | 5:20 | 18–65 | CLBP: Physiotherapy Department of National Health Service | Scotland | Purposive sampling based on location of physical therapy practice (urban or rural), gender, age, and management style (group, one-to-one, or mixed) | Semistructured interviews | Framework analysis—data management, descriptive analysis, and explanatory analysis | Post hoc operationalization: via interviewing physical therapists “Good communication involved: taking time over explanations; using appropriate terminology; and encouraging the patient’s participation in the communication process” |

| To contribute to wider evidence base as to how PTs understand and deal with non-specific CLBP disorders from BPS perspective, and perceived barriers to provision of BPS model of care delivery in primary care setting Cowell et al,45 2018 | 10:0 | 7:3 | 18–70: 4–14+ | NR | NR | Nonspecific CLBP: primary care | England | Purposive sampling based on sex, age, and clinical experience | Semistructured face-to-face qualitative interviews | Thematic analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To identify elements of PT–patient interaction considered by patients when they evaluate quality of care in outpatient rehabilitation settings Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | 0:57 | NR | NR | 33:24 | 18+ | Chronic musculoskeletal pain: post-acute outpatient rehabilitation clinic | Spain | Purposive sampling based on age, gender, and clinical condition | Audiotaped focus group interviews | Thematic analysis using modified grounded theory approach | No explicit operationalization |

| To investigate how many and what verbally expressed emotions PTs state during interviews between PTs and patients Gard et al,41 2000 | 10:0 | 0:10 | 44–62: 7–41 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: clinical health tutors in primary health care, tutoring physical therapy | Sweden | Purposive sampling based on clinical specialties | Qualitative case series | Cross-case analysis | A priori operationalization: categorization of emotions by Tomkins65,66 (1962, 1984) and Izard67 (1977) |

| To describe communicative patterns about change in demanding physical therapy treatment situations Øien et al,47 2011 | 6:11 | 1:5 | 44–68: 20–47 | 1:10 | 22–47 | Chronic muscular pain located in back and/or neck: outpatient clinic | Norway | Convenience | Interviews, patients’ notes, videorecorded treatment sessions, and researchers’ field notes | Løvlie – Schibbye’s part process analysis | A priori operationalization based on System Theory of Communication: “The theme is often verbally communicated. The meta-communication encompasses nonverbal emotional expressions related to the theme. The theme the meta-communication structure define the relationship… Communication is based on the observable manifestations of the relationship. All behavior—including speech, tone of voice, silence, withdrawal, immobility or denial—is communication.” |

| To explore how French-speaking PTs and patients with LBP explore and assess patient’s pain experience during initial encounters Opsommer and Schoeb,48 2014 | 2:6 | NR | NR: 0–20 | 4:2 | 18+ | CLBP: university hospital and private practice | Switzerland | Convenience | Videotaped initial encounters | Conversation analysis | Post hoc operationalization via conversation analytic components |

| To investigate prevalence of long-term treatment and identify and classify reasons why PT clinicians continue to treat LBP patients in absence of objective improvement Pincus et al,49 2006 | 21:0 for interviews; 354:0 for surveys | NR (interviews); 71:283 (surveys) | NR for interviews; 20–60+ for surveys: mean 12.8 (SD NR) for interviews; NR for surveys | NR | NR | CLBP: National Health Service primary and secondary care, or private practice | England | Combination of stratified and purposive sampling based on age, gender, and private/public practice setting | Interviews and surveys | Mixed methods: grounded theory analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To explore PTs’ perspectives about patients with incomplete posttraumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home exercises Serpanou et al,50 2019 | 13:0 | 7:6 | 30–47: 5–22 | NR | NR | Posttraumatic paraplegia: home health services | Greece | Convenience | Semistructured interviews | Qualitative content analysis | Post hoc operationalization from interviewing PTs: “All participants agree that good communication with the patient helps in overcoming obstacles. Communication is a 2-way process between the physical therapist and the patient, and it is necessary in order to understand each other’s problems and expectations.” |

| To answer research question: “What are PTs’ perspectives on managing the cognitive, psychological, and social dimensions of CLBP after intensive biopsychosocial training?” Synnott et al,51 2016 | 13:0 | 9:4 | 30–47: mean 13 (SD = 3.8) | NR | NR | CLBP: NR | Belgium, Australia, Denmark, Ireland | Purposive | Audiotaped interviews | Interpretive descriptive analysis | No explicit operationalization |

aTable includes an abbreviated list of extracted data elements based on Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. The complete data extraction table is available upon request from the corresponding author. BPS = biopsychosocial; CLBP = chronic low back pain; F = female; LBP = low back pain; M = male; NR = not reported; PT = physical therapist.

bValues listed indicate range of minimum-to-maximum years, unless otherwise indicated. Mean and SD included only for studies that reported these data.

cSampling method applies to both PTs and patients where both groups were recruited.

| Study Aim(s) . | No., PT: Patient . | PT Sex, M:F . | PT Age: Years of Clinical Experienceb . | Patient Sex, M:F . | Patient Age, yb . | Pain Condition: Treatment Setting . | Country . | Sampling Procedurec . | Data Collection Method(s) . | Data Analysis Method(s) . | Communication Operationalization . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To find out how PTs experienced influence of systematically prepared key questioning on their relation to and understanding of patients with long-standing pain Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | 6:80 | NR | 39–62: 10–25 | Majority female | 18–70 | Chronic pain without serious causative or contributory disease: pain rehabilitation clinics, primary care, Feldenkrais private practice | Sweden | Convenience | Focus group interviews | Phenomenography | A priori operationalization: “By communication method for the encounter between physiotherapist and patient we mean a method which combines an ethical attitude with conscious speech acts and sensitivity to the patient’s body experience” |

| (1) To determine factors that affected PTs’ perception of patients’ pain and (2) determine how this perception affected patient management Askew et al,33 1998 | 46:0 | 19:27 | 25–48: 2–25 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: pain management outpatient orthopedic and sports medicine clinics | USA | Convenience | Structured interviews | Coded, included quotes from interviews for thematic categories | No explicit operationalization |

| To define patient-centeredness from patient’s perspective in context of physical therapy for CLBP Cooper et al,44 2008 | 0:25 | NR | NR | 5:20 | 18–65 | CLBP: Physiotherapy Department of National Health Service | Scotland | Purposive sampling based on location of physical therapy practice (urban or rural), gender, age, and management style (group, one-to-one, or mixed) | Semistructured interviews | Framework analysis—data management, descriptive analysis, and explanatory analysis | Post hoc operationalization: via interviewing physical therapists “Good communication involved: taking time over explanations; using appropriate terminology; and encouraging the patient’s participation in the communication process” |

| To contribute to wider evidence base as to how PTs understand and deal with non-specific CLBP disorders from BPS perspective, and perceived barriers to provision of BPS model of care delivery in primary care setting Cowell et al,45 2018 | 10:0 | 7:3 | 18–70: 4–14+ | NR | NR | Nonspecific CLBP: primary care | England | Purposive sampling based on sex, age, and clinical experience | Semistructured face-to-face qualitative interviews | Thematic analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To identify elements of PT–patient interaction considered by patients when they evaluate quality of care in outpatient rehabilitation settings Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | 0:57 | NR | NR | 33:24 | 18+ | Chronic musculoskeletal pain: post-acute outpatient rehabilitation clinic | Spain | Purposive sampling based on age, gender, and clinical condition | Audiotaped focus group interviews | Thematic analysis using modified grounded theory approach | No explicit operationalization |

| To investigate how many and what verbally expressed emotions PTs state during interviews between PTs and patients Gard et al,41 2000 | 10:0 | 0:10 | 44–62: 7–41 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: clinical health tutors in primary health care, tutoring physical therapy | Sweden | Purposive sampling based on clinical specialties | Qualitative case series | Cross-case analysis | A priori operationalization: categorization of emotions by Tomkins65,66 (1962, 1984) and Izard67 (1977) |

| To describe communicative patterns about change in demanding physical therapy treatment situations Øien et al,47 2011 | 6:11 | 1:5 | 44–68: 20–47 | 1:10 | 22–47 | Chronic muscular pain located in back and/or neck: outpatient clinic | Norway | Convenience | Interviews, patients’ notes, videorecorded treatment sessions, and researchers’ field notes | Løvlie – Schibbye’s part process analysis | A priori operationalization based on System Theory of Communication: “The theme is often verbally communicated. The meta-communication encompasses nonverbal emotional expressions related to the theme. The theme the meta-communication structure define the relationship… Communication is based on the observable manifestations of the relationship. All behavior—including speech, tone of voice, silence, withdrawal, immobility or denial—is communication.” |

| To explore how French-speaking PTs and patients with LBP explore and assess patient’s pain experience during initial encounters Opsommer and Schoeb,48 2014 | 2:6 | NR | NR: 0–20 | 4:2 | 18+ | CLBP: university hospital and private practice | Switzerland | Convenience | Videotaped initial encounters | Conversation analysis | Post hoc operationalization via conversation analytic components |

| To investigate prevalence of long-term treatment and identify and classify reasons why PT clinicians continue to treat LBP patients in absence of objective improvement Pincus et al,49 2006 | 21:0 for interviews; 354:0 for surveys | NR (interviews); 71:283 (surveys) | NR for interviews; 20–60+ for surveys: mean 12.8 (SD NR) for interviews; NR for surveys | NR | NR | CLBP: National Health Service primary and secondary care, or private practice | England | Combination of stratified and purposive sampling based on age, gender, and private/public practice setting | Interviews and surveys | Mixed methods: grounded theory analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To explore PTs’ perspectives about patients with incomplete posttraumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home exercises Serpanou et al,50 2019 | 13:0 | 7:6 | 30–47: 5–22 | NR | NR | Posttraumatic paraplegia: home health services | Greece | Convenience | Semistructured interviews | Qualitative content analysis | Post hoc operationalization from interviewing PTs: “All participants agree that good communication with the patient helps in overcoming obstacles. Communication is a 2-way process between the physical therapist and the patient, and it is necessary in order to understand each other’s problems and expectations.” |

| To answer research question: “What are PTs’ perspectives on managing the cognitive, psychological, and social dimensions of CLBP after intensive biopsychosocial training?” Synnott et al,51 2016 | 13:0 | 9:4 | 30–47: mean 13 (SD = 3.8) | NR | NR | CLBP: NR | Belgium, Australia, Denmark, Ireland | Purposive | Audiotaped interviews | Interpretive descriptive analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| Study Aim(s) . | No., PT: Patient . | PT Sex, M:F . | PT Age: Years of Clinical Experienceb . | Patient Sex, M:F . | Patient Age, yb . | Pain Condition: Treatment Setting . | Country . | Sampling Procedurec . | Data Collection Method(s) . | Data Analysis Method(s) . | Communication Operationalization . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To find out how PTs experienced influence of systematically prepared key questioning on their relation to and understanding of patients with long-standing pain Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | 6:80 | NR | 39–62: 10–25 | Majority female | 18–70 | Chronic pain without serious causative or contributory disease: pain rehabilitation clinics, primary care, Feldenkrais private practice | Sweden | Convenience | Focus group interviews | Phenomenography | A priori operationalization: “By communication method for the encounter between physiotherapist and patient we mean a method which combines an ethical attitude with conscious speech acts and sensitivity to the patient’s body experience” |

| (1) To determine factors that affected PTs’ perception of patients’ pain and (2) determine how this perception affected patient management Askew et al,33 1998 | 46:0 | 19:27 | 25–48: 2–25 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: pain management outpatient orthopedic and sports medicine clinics | USA | Convenience | Structured interviews | Coded, included quotes from interviews for thematic categories | No explicit operationalization |

| To define patient-centeredness from patient’s perspective in context of physical therapy for CLBP Cooper et al,44 2008 | 0:25 | NR | NR | 5:20 | 18–65 | CLBP: Physiotherapy Department of National Health Service | Scotland | Purposive sampling based on location of physical therapy practice (urban or rural), gender, age, and management style (group, one-to-one, or mixed) | Semistructured interviews | Framework analysis—data management, descriptive analysis, and explanatory analysis | Post hoc operationalization: via interviewing physical therapists “Good communication involved: taking time over explanations; using appropriate terminology; and encouraging the patient’s participation in the communication process” |

| To contribute to wider evidence base as to how PTs understand and deal with non-specific CLBP disorders from BPS perspective, and perceived barriers to provision of BPS model of care delivery in primary care setting Cowell et al,45 2018 | 10:0 | 7:3 | 18–70: 4–14+ | NR | NR | Nonspecific CLBP: primary care | England | Purposive sampling based on sex, age, and clinical experience | Semistructured face-to-face qualitative interviews | Thematic analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To identify elements of PT–patient interaction considered by patients when they evaluate quality of care in outpatient rehabilitation settings Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | 0:57 | NR | NR | 33:24 | 18+ | Chronic musculoskeletal pain: post-acute outpatient rehabilitation clinic | Spain | Purposive sampling based on age, gender, and clinical condition | Audiotaped focus group interviews | Thematic analysis using modified grounded theory approach | No explicit operationalization |

| To investigate how many and what verbally expressed emotions PTs state during interviews between PTs and patients Gard et al,41 2000 | 10:0 | 0:10 | 44–62: 7–41 | NR | NR | Persistent pain: clinical health tutors in primary health care, tutoring physical therapy | Sweden | Purposive sampling based on clinical specialties | Qualitative case series | Cross-case analysis | A priori operationalization: categorization of emotions by Tomkins65,66 (1962, 1984) and Izard67 (1977) |

| To describe communicative patterns about change in demanding physical therapy treatment situations Øien et al,47 2011 | 6:11 | 1:5 | 44–68: 20–47 | 1:10 | 22–47 | Chronic muscular pain located in back and/or neck: outpatient clinic | Norway | Convenience | Interviews, patients’ notes, videorecorded treatment sessions, and researchers’ field notes | Løvlie – Schibbye’s part process analysis | A priori operationalization based on System Theory of Communication: “The theme is often verbally communicated. The meta-communication encompasses nonverbal emotional expressions related to the theme. The theme the meta-communication structure define the relationship… Communication is based on the observable manifestations of the relationship. All behavior—including speech, tone of voice, silence, withdrawal, immobility or denial—is communication.” |

| To explore how French-speaking PTs and patients with LBP explore and assess patient’s pain experience during initial encounters Opsommer and Schoeb,48 2014 | 2:6 | NR | NR: 0–20 | 4:2 | 18+ | CLBP: university hospital and private practice | Switzerland | Convenience | Videotaped initial encounters | Conversation analysis | Post hoc operationalization via conversation analytic components |

| To investigate prevalence of long-term treatment and identify and classify reasons why PT clinicians continue to treat LBP patients in absence of objective improvement Pincus et al,49 2006 | 21:0 for interviews; 354:0 for surveys | NR (interviews); 71:283 (surveys) | NR for interviews; 20–60+ for surveys: mean 12.8 (SD NR) for interviews; NR for surveys | NR | NR | CLBP: National Health Service primary and secondary care, or private practice | England | Combination of stratified and purposive sampling based on age, gender, and private/public practice setting | Interviews and surveys | Mixed methods: grounded theory analysis | No explicit operationalization |

| To explore PTs’ perspectives about patients with incomplete posttraumatic paraplegia adherence to recommended home exercises Serpanou et al,50 2019 | 13:0 | 7:6 | 30–47: 5–22 | NR | NR | Posttraumatic paraplegia: home health services | Greece | Convenience | Semistructured interviews | Qualitative content analysis | Post hoc operationalization from interviewing PTs: “All participants agree that good communication with the patient helps in overcoming obstacles. Communication is a 2-way process between the physical therapist and the patient, and it is necessary in order to understand each other’s problems and expectations.” |

| To answer research question: “What are PTs’ perspectives on managing the cognitive, psychological, and social dimensions of CLBP after intensive biopsychosocial training?” Synnott et al,51 2016 | 13:0 | 9:4 | 30–47: mean 13 (SD = 3.8) | NR | NR | CLBP: NR | Belgium, Australia, Denmark, Ireland | Purposive | Audiotaped interviews | Interpretive descriptive analysis | No explicit operationalization |

aTable includes an abbreviated list of extracted data elements based on Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. The complete data extraction table is available upon request from the corresponding author. BPS = biopsychosocial; CLBP = chronic low back pain; F = female; LBP = low back pain; M = male; NR = not reported; PT = physical therapist.

bValues listed indicate range of minimum-to-maximum years, unless otherwise indicated. Mean and SD included only for studies that reported these data.

cSampling method applies to both PTs and patients where both groups were recruited.

Operationalization of Communication Terminology

Because most of the included studies aimed to explore communication as a phenomenon rather than operationalize terminology, communication terms differed across studies, and the level of specificity operationalizing communication and competent, effective, or preferred communication varied widely (Tab. 1). Most included studies did not conceptualize or operationalize communication with replicable specificity. Only 3 of 11 studies44,47,50 operationalized communication terms prior to data collection, although there were widely differing presentations of communication as a phenomenon even among these studies. Two studies acknowledged the interactive, reciprocal nature of communication and underscored its importance for clinical practice. These studies characterized communication as “a 2-way process between the physical therapist and the patient … necessary in order to understand each other,”50 and “physiotherapy and communication were inseparable processes. The physiotherapist and the patient concurrently participated.”47 The third study concluded that “good communication involved: taking time over explanations; using appropriate terminology; and encouraging the patient’s participation in the communication process.”44 This definition of good communication was context specific, supported by quotations, and descriptive enough to be easily understood and replicated. Five studies33,45,46,48,50 made no attempt to operationalize communication, instead using positively valanced but ultimately ambiguous terms such as “careful communication,”45 “effective communication,”45,48 “communication skills/style/process,”33,48,50 or “respectful communication”46 without specifying why and how preferred communication was structured.

Thematic Findings for Communication Behaviors

By analyzing representative quotations and descriptions of communication used by physical therapists, we consolidated different terms for communication behaviors that had the same or similar meaning. We also separated communication behaviors with vague identifiers of effectiveness, such as “good communication” or “effective communication,” into behaviorally distinct categories for preferred communication behaviors. A preliminary analysis of communication behaviors identified 25 subthemes, which were then organized into 8 emergent communication themes, named for their presumed purpose in interpersonal interactions between physical therapists and their patients: (1) disclosure-facilitating, (2) rapport-building, (3) empathic, (4) collaborative, (5) professional accountability, (6) informative, (7) agenda-setting, and (8) meta-communication. We present in the Supplementary Table abstracted findings for preferred communication behaviors used by physical therapists during chronic pain rehabilitation organized by subthemes and themes and supported by quotations extracted from included studies.

Theme 1: Disclosure-Facilitating Communication

Physical therapists used several verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors to encourage patients to disclose personal information in interactions, such as using open-ended questions/formulations, gaze and nodding as conversation continuers, and asking about lifestyle.43,45,48,50,51 Studies varied in their level of specificity when describing these communication behaviors. For example, 1 study was vague with their recommendation for disclosure-facilitating communication, underscoring the importance of open lines of communication and availability without describing how this was accomplished other than confirming it was a part of care: “my communication with the patients is open. Any time the patients can call me and tell me their problems.”50 Another study described exactly how disclosure-facilitating communication was enacted, with pilot testing of specific open-ended questions used during pain rehabilitation.43

Theme 2: Rapport-Building Communication

Much of this communication focused on physical therapists creating an atmosphere to foster trust. These studies relied on general recommendations and often did not identify what, specifically, about the communication enabled rapport. These articles recommended physical therapists “develop a good initial relationship with the patient”33 and that “friendly and respectful behavior of physiotherapists was a predominant patient experience.”46 The specific rapport-building practices discussed were listening,43 using humor,41 and tailoring communication to the individual being treated.44,50 In this category, preferred and disfavored communication were discussed in tandem: “specific approaches were more useful for some than others, suggesting that tailoring communication to the individual’s needs is important,” but that “written communication was also discussed, often in a negative manner, suggesting that care should be taken to issue information acceptable to the individual.”44 Listening was emphasized alongside the negative consequences of not listening “if you don’t [listen] then you will never be able to pull them out because you aren’t listening.”43

Theme 3: Empathic Communication

Empathic communication emerged as a category distinct from rapport-building communication in that rapport-building was more focused on communicating in a way that fostered trust, whereas empathic communication was more focused on identifying and attending to emotional matters. Similar to rapport-building, listening was understood as a key communication behavior but with the stipulation that listening be paired with encouraging, working with, and not judging patients.33 Empathic communication also involved using touch to communicate a strong and supportive relationship and relaying personal pain experiences to patients.33 Timing along with delivery were considered important in this category: “early follow-up support was considered optimal for reinforcement and to reassure anxious patients”45 and “the amount of time I spend with a patient … makes them believe they can get better.”33 Physical therapists acknowledged several challenges with empathic communication, such as difficulty responding to sad emotions displayed by their patients. Physical therapists acknowledged that these situations were difficult, but they preferred their patients to display their emotions because “expression of feelings in the clinic facilitates the physiotherapist’s understanding of the patient’s problems and influences the result of treatment positively.”43

Theme 4: Collaborative Communication

Collaborative communication included communication behaviors such as seeking common ground47 and treating communication as a 2-way street.50 One article described the importance of “collaboratively agreeing [upon] treatment goals,”45 which was identical in practice and definition to “shared decision-making” in the health care literature, illustrating the lack of standardization when describing communication behaviors in clinical practice. Successful collaborative communication centered around the goal of ensuring individuals felt involved in their own care, engaging in communication behavior like “taking time over explanations; using appropriate terminology; listening, understanding and getting to know the patient; and encouraging the patient’s participation in the communication process.”44 Involvement did not necessarily require individuals to be joint decision makers in their own care; participants were comfortable with their physical therapists making final decisions about their care “as long as they were accompanied by good explanations.”44

Theme 5: Professional Accountability Communication

A few studies considered communication that involved admitting limitations in professional skills or knowledge and asking for help when needed to be an important indicator of a good physical therapist. In 1 extracted quotation, a physical therapist described in what context it would be appropriate to refer a patient to someone else and words that could be used to do so: “…there is somebody who has 10 years more experience than me, why don’t you go and see them. There are so many therapies about.”49 Another physical therapist recommended “not being afraid to admit your limitations and ask for help if it is needed.”41

Theme 6: Informative Communication

Physical therapists extracted and relayed information in different yet connected ways: providing education and information,44,46 reconciling patient perspectives,45,51 developing patient insights,45 and reconciling information from verbal and nonverbal (eg, postures/movements, pain behaviors) communication cues during presentations of pain.33 Preferred communication was described as regular updates and correcting misguided patient beliefs. One study described how to correct individual’s incorrect perceptions and face conflict to ensure quality care: “now I’m more inclined to say ‘Listen, hold on a minute. Anyway, I’ve just got to re-examine your point of view on this’ and that can sometimes lead to conflict… but I think you sometimes need conflict for conceptual change.”51 In this category, the term “effective communication” was often used when more specific terminology would be useful for physical therapists wanting to improve their skills in information exchange. For example, 1 article45 used “effective communication” and “educating and developing patient insights” interchangeably.

Theme 7: Agenda-Setting Communication

Although only 1 study contributed to this theme,48 this type of communication was included as a standalone category because it is entirely distinct from the other behaviors identified in our analysis. Agenda-setting is a communication practice in which providers organize and guide conversations to prioritize selected topics or tasks during an interpersonal encounter that may be constrained by time; this can include shifting topics, shutting down a topic of conversation, or ensuring that a topic gets covered before the end of a visit.43 Physical therapists related that strategies to close down a pain conversation were to “summarize the consultation and to include a prognosis of the patient’s problem.”48 Physical therapists also described shifting from one topic to another through the strategic use of yes/no questions and “okay” terminators.

Theme 8: Meta-Communication

A final emergent theme was the use of meta-communication or communicating about communication. Because many of these studies interviewed physical therapists about their communication, interviewees were primed to contribute to this theme. Interestingly, physical therapists most often discussed using meta-communication as a tool for facilitating disclosure with their patients. We recognized this theme as distinct from disclosure-facilitating communication because it was mentioned by name in extracted quotations, although meta-communication and disclosure-facilitating communication shared the same goals in some studies. In 1 study, physical therapists asked their patients the open-ended question “‘If pain could talk, what would it say?’—an aspect of metacommunication was introduced, where patient and physiotherapist together reflected, giving new perspectives on the experience of pain.” In this example, physical therapists encouraged participants to communicate about their communication through a third party anthropomorphized concept—their own pain as a human being with the ability to use language.43 Physical therapists acknowledged that “communication about communication, appeared as means to open locked dialogues, and was initiated by the physiotherapists and the patients,” suggesting that both physical therapists and participants found meta-communication to be a helpful tool in furthering understanding.47

Descriptive Findings for Secondary Variables

Intermediary and terminal variables cited as being linked to communication behaviors in the primary review and potentially important for patient outcomes are highlighted in the Supplementary Table. Overall, these variables were infrequently mentioned, varied widely across studies and communication themes, and were not operationally defined; thus, a thematic analysis was not performed. The most frequently cited intermediary variables included various terms related to the constructs of therapeutic alliance (encompassing trusting relationships/rapport33,41,49 and collaboration on tasks and goals45,47); informational and emotional disclosures by the participant43,45,48; and delivery of high-quality patient-centered care by the physical therapist.41,43,44,47,50 Less frequently cited intermediary variables included adherence,45,50 expectations for recovery,45,47 and perceptions of quality service by the patient.47 Terminal patient outcomes were rarely cited as being directly impacted by communication behaviors, with only a single study identifying specific treatment outcomes (pain and activity)45 and the remainder using vague descriptors such as “the result of treatment.”43

Methodological Quality of Included Studies and Quality of Evidence

Results of the CASP methodological quality appraisal are presented in Table 2. Only 2 studies met all the methodological criteria,46,50 and 1 study failed as many as 5 of the 10 CASP criteria.43 On average, the 11 studies failed 2.1(1.5) CASP criteria. Consideration of potential bias or influence in the relationship between the researcher and participants (Criterion 6, reflexivity) and thorough description of the study design (Criterion 3) were the most frequently violated criteria. All included studies provided a clear statement of aim, appropriate qualitative methodology for that stated aim based on Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research criteria, and a statement of findings with claims supported by participant quotes (Criteria 1, 2, and 9).

| Study . | Criterion 1b . | Criterion 2b . | Criterion 3b . | Criterion 4b . | Criterion 5b . | Criterion 6b . | Criterion 7b . | Criterion 8b . | Criterion 9b . | Criterion 10b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear |

| Askew et al,33 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cooper et al44 2008 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cowell et al,45 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gard et al,41 2000 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Øien et al,47 2011 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Opsommer and Schoeb48 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pincus et al,49 2006 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Serpanou et al,50 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Synnott et al,51 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Study . | Criterion 1b . | Criterion 2b . | Criterion 3b . | Criterion 4b . | Criterion 5b . | Criterion 6b . | Criterion 7b . | Criterion 8b . | Criterion 9b . | Criterion 10b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear |

| Askew et al,33 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cooper et al44 2008 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cowell et al,45 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gard et al,41 2000 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Øien et al,47 2011 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Opsommer and Schoeb48 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pincus et al,49 2006 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Serpanou et al,50 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Synnott et al,51 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

aCASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

bCriteria: 1 = Clear Statement of Aim; 2 = Qualitative Methodology Appropriate; 3 = Appropriate Research Design; 4 = Sampling; 5 = Data Collection; 6 = Research Reflexivity; 7 = Ethical Consideration; 8 = Appropriate Data Analysis; 9 = Clear Statement of Findings; 10 = Research Value.

| Study . | Criterion 1b . | Criterion 2b . | Criterion 3b . | Criterion 4b . | Criterion 5b . | Criterion 6b . | Criterion 7b . | Criterion 8b . | Criterion 9b . | Criterion 10b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear |

| Askew et al,33 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cooper et al44 2008 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cowell et al,45 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gard et al,41 2000 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Øien et al,47 2011 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Opsommer and Schoeb48 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pincus et al,49 2006 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Serpanou et al,50 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Synnott et al,51 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Study . | Criterion 1b . | Criterion 2b . | Criterion 3b . | Criterion 4b . | Criterion 5b . | Criterion 6b . | Criterion 7b . | Criterion 8b . | Criterion 9b . | Criterion 10b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear |

| Askew et al,33 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cooper et al44 2008 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cowell et al,45 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gard et al,41 2000 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Øien et al,47 2011 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Opsommer and Schoeb48 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pincus et al,49 2006 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Serpanou et al,50 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Synnott et al,51 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

aCASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

bCriteria: 1 = Clear Statement of Aim; 2 = Qualitative Methodology Appropriate; 3 = Appropriate Research Design; 4 = Sampling; 5 = Data Collection; 6 = Research Reflexivity; 7 = Ethical Consideration; 8 = Appropriate Data Analysis; 9 = Clear Statement of Findings; 10 = Research Value.

Results of the sensitivity analysis are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. The greatest number of studies contributing to a theme was for rapport-building communication (6 studies), followed by informative communication (5 studies), disclosure-facilitating communication and collaborative communication (4 studies each), and empathic communication (3 studies). The themes supported by the fewest number of studies were professional accountability and meta-communication (2 studies each) as well as agenda-setting communication (1 study).

Based on overall quality of the available evidence from the GRADE-CERQual assessment, confidence was judged to be moderate for 4 communication themes (disclosure-facilitating, rapport-building, empathic, and collaborative communication) and low for 4 themes (professional accountability, informative, agenda-setting, and meta-communication; Tab. 3). Limited operationalization of communication (ie, poor coherence) was the most common reason for lower confidence ratings, with moderate to serious concerns for all 8 communication themes. Lack of variety in rich quotations (ie, poor adequacy of data) distinguished lower- from higher-quality evidence, with moderate to serious concerns for all communication themes judged to have low confidence and only minor concerns for themes with higher confidence. Moderate methodological concerns identified by CASP contributed to low confidence ratings for 3 of the 4 themes with this rating. Relevance of data to the phenomena of interest contributed least to confidence ratings, with moderate concerns for only 2 communication themes.

Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE-CERQual) Quality-of-Evidence Appraisala

| Goal-Directed Communication Theme . | Studies Contributing to Theme . | Assessment of: . | Overall Confidence . | Rationale for Judgment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methodological Limitations (CASP)b . | Adequacy of Data . | Coherence . | Relevance . | ||||

| Disclosure-facilitating communication | Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010; Cowell et al,45 2018; Opsommer and Schoeb48 2014; Serpanou et al,50 2019; Synnott et al,51 2016 | Minor concerns Low,43 moderate,48 high19,45,50,51 40/50 (80%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from 3/5 studies Majority provided age Majority provided sex 8 countries represented | Moderate concerns 5 studies supported themec 1/5 studies operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 4/5 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study assessed chronic pain as symptom in those diagnosed with posttraumatic paraplegia | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns about operationalization of communication, with only minor concerns for all other categories |

| Rapport-building communication | Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010; Askew et al,33 1998; Cooper et al,44 2008; Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014; Gard et al,41 2000; Pincus et al,49 2006; Serpanou et al,50 2019 | Moderate concerns Low,43 moderate,49 high33,44,46,50 54/70 (77%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from all 7 studies Majority provided age Majority provided sex 6 countries represented | Moderate concerns 7 studies supported themec 2/7 studies operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Moderate concerns 4/7 studies assessed chronic pain as symptom in persistent pain rehabilitation, musculoskeletal disorders, posttraumatic paraplegia, or chronic pain without serious causative or contributary disease 1 study included osteopaths and chiropractors in interviews along with PTs | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns for methodological rigor, operationalization of communication, and focus on phenomena of interest |

| Empathic communication | Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010; Askew et al,33 1998; Cowell et al,45 2018; Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | Minor concerns Low,43 high33,45,46 32/40 (80%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from 3/4 studies All provided age Majority provided sex 4 countries represented | Serious concerns 4 studies supported themec None operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 1/2 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 2 studies assessed chronic pain as symptom in musculoskeletal disorder or chronic pain without serious causative or contributory disease | Moderate confidence | Serious concerns about operationalization of communication, with only minor concerns for all other categories |

| Collaborative communication | Cooper et al,44 2008; Cowell et al,45 2018; Øien et al,47 2011; Serpanou et al,50 2019 | No or very minor concerns High44,45,47,50 35/40 (88%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from 3/4 studies Half provided age All provided sex 4 countries represented | Moderate concerns 4 studies supported themec 1/4 studies operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 3/4 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study assessed chronic pain as symptom in posttraumatic paraplegia | Moderate confidence | High methodological rigor and focus on phenomena of interest, with moderate concerns for operationalization of communication |

| Professional accountability communication | Gard et al,41 2000; Pincus et al,49 2006 | Moderate concerns Moderate41,49 13/20 (65%) criteria met | Serious concerns Limited quotes from studies and only 2 studies contributed to theme 1 provided age 1 provided sex 2 countries represented | Serious concerns 2 studies supported themec None operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Moderate concerns 2/2 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study included osteopaths and chiropractors in interviews along with PTs | Low confidence | Moderate concerns with methodological rigor and focus on phenomena of interest, with serious concerns for richness of quotes and operationalization of communication |

| Informative communication | Askew et al,33 1998; Cooper et al,44 2008; Cowell et al,45 2018; Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014; Synnott et al,51 2016 | Minor concerns Low,33 high44–46,51 41/50 (82%) criteria met | Moderate concerns Limited quotes from all studies All provided age All provided sex 7 countries represented | Serious concerns 4 studies supported themec None operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 3/4 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study assessed chronic pain as symptom in musculoskeletal disorder | Low confidence | Despite high methodological rigor, moderate concerns with variety of quotes and serious concerns about operationalization of communication |

| Agenda-setting communication | Opsommer and Schoeb, 201448 | Moderate concerns Moderate48 7/10 (70%) criteria met | Serious concerns Rich quotes, but only 1 study contributing to theme Age not provided Sex not provided 1 country represented | Serious concerns 1 study supported themec Study did not operationalize communication clearly or with direct support from quotes | No or very minor concerns Study assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria | Low confidence | Despite strong focus on phenomena of interest, moderate concerns with methodological rigor and serious concerns with adequacy of data and operationalization of communication |

| Meta-communication | Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010; Øien et al,47 2011 | Moderate concerns Low,43 high47 13/20 (65%) criteria met | Serious concerns Rich quotes from studies, but only 2 studies contributing to theme All studies provided age Majority provided sex 2 countries represented | Serious concerns 2 studies supported themec 1/2 studies operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 1/2 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study assessed chronic pain as symptom in chronic pain without serious causative or contributory disease | Low confidence | Though supporting quotes are rich, serious concerns with adequacy of data from 2 studies, with communication operationalized by only 1 study |

| Goal-Directed Communication Theme . | Studies Contributing to Theme . | Assessment of: . | Overall Confidence . | Rationale for Judgment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methodological Limitations (CASP)b . | Adequacy of Data . | Coherence . | Relevance . | ||||

| Disclosure-facilitating communication | Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010; Cowell et al,45 2018; Opsommer and Schoeb48 2014; Serpanou et al,50 2019; Synnott et al,51 2016 | Minor concerns Low,43 moderate,48 high19,45,50,51 40/50 (80%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from 3/5 studies Majority provided age Majority provided sex 8 countries represented | Moderate concerns 5 studies supported themec 1/5 studies operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 4/5 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study assessed chronic pain as symptom in those diagnosed with posttraumatic paraplegia | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns about operationalization of communication, with only minor concerns for all other categories |

| Rapport-building communication | Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010; Askew et al,33 1998; Cooper et al,44 2008; Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014; Gard et al,41 2000; Pincus et al,49 2006; Serpanou et al,50 2019 | Moderate concerns Low,43 moderate,49 high33,44,46,50 54/70 (77%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from all 7 studies Majority provided age Majority provided sex 6 countries represented | Moderate concerns 7 studies supported themec 2/7 studies operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Moderate concerns 4/7 studies assessed chronic pain as symptom in persistent pain rehabilitation, musculoskeletal disorders, posttraumatic paraplegia, or chronic pain without serious causative or contributary disease 1 study included osteopaths and chiropractors in interviews along with PTs | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns for methodological rigor, operationalization of communication, and focus on phenomena of interest |

| Empathic communication | Afrell and Rudebeck43 2010; Askew et al,33 1998; Cowell et al,45 2018; Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014 | Minor concerns Low,43 high33,45,46 32/40 (80%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from 3/4 studies All provided age Majority provided sex 4 countries represented | Serious concerns 4 studies supported themec None operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 1/2 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 2 studies assessed chronic pain as symptom in musculoskeletal disorder or chronic pain without serious causative or contributory disease | Moderate confidence | Serious concerns about operationalization of communication, with only minor concerns for all other categories |

| Collaborative communication | Cooper et al,44 2008; Cowell et al,45 2018; Øien et al,47 2011; Serpanou et al,50 2019 | No or very minor concerns High44,45,47,50 35/40 (88%) criteria met | Minor concerns Variety of rich quotes supportive of theme from 3/4 studies Half provided age All provided sex 4 countries represented | Moderate concerns 4 studies supported themec 1/4 studies operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 3/4 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study assessed chronic pain as symptom in posttraumatic paraplegia | Moderate confidence | High methodological rigor and focus on phenomena of interest, with moderate concerns for operationalization of communication |

| Professional accountability communication | Gard et al,41 2000; Pincus et al,49 2006 | Moderate concerns Moderate41,49 13/20 (65%) criteria met | Serious concerns Limited quotes from studies and only 2 studies contributed to theme 1 provided age 1 provided sex 2 countries represented | Serious concerns 2 studies supported themec None operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Moderate concerns 2/2 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study included osteopaths and chiropractors in interviews along with PTs | Low confidence | Moderate concerns with methodological rigor and focus on phenomena of interest, with serious concerns for richness of quotes and operationalization of communication |

| Informative communication | Askew et al,33 1998; Cooper et al,44 2008; Cowell et al,45 2018; Del Baño-Aledo et al,46 2014; Synnott et al,51 2016 | Minor concerns Low,33 high44–46,51 41/50 (82%) criteria met | Moderate concerns Limited quotes from all studies All provided age All provided sex 7 countries represented | Serious concerns 4 studies supported themec None operationalized communication clearly and with direct support from quotes | Minor concerns 3/4 studies assessed communication in PTs treating chronic pain as per inclusion criteria 1 study assessed chronic pain as symptom in musculoskeletal disorder | Low confidence | Despite high methodological rigor, moderate concerns with variety of quotes and serious concerns about operationalization of communication |