-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abdullahi Aborode, Wireko Andrew Awuah, Aashna Mehta, Abdul-Rahman Toufik, Shahzaib Ahmad, Anna Chiara Corriero, Ana Carla dos Santos Costa, Esther Patience Nansubuga, Elif Gecer, Katerina Namaal Bel-Nono, Aymar Akilimali, Christian Inya Oko, Yves Miel H Zuñiga, COVID-19, bubonic and meningitis in Democratic Republic of Congo: the confluence of three plagues at a challenging time, Postgraduate Medical Journal, Volume 99, Issue 1169, March 2023, Pages 93–95, https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-141433

Close - Share Icon Share

Introduction

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) witnessed the foremost case of COVID-19 on 10 March 2020. The caseload further increased, with 10 630 points recorded and 272 deaths as of 28 September 2020 [1]. The number of novel cases of COVID-19 is constantly upsurging with a test positivity rate of 21% [1]. The latest update as of 13 March 2022 disclosed 86 315 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with over 34 000 active patients and 1335 deaths [2]. DRC COVID-19 vaccination rate is also low, as only 110 634 out of the 1 054 720 COVID-19 vaccination doses received as of 22 September 2021 were deployed. This accounts for just 0.03% of the entire population being fully vaccinated since April 2021, when the country began its vaccination [3].

Various exacerbating factors contributing to a poor healthcare system in DRC include conflict, healthcare resource constraint and exhaustion, poor infrastructure, insufficient logistical resources, limited testing centres, lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and conflicting interests of the stakeholders. All these factors contribute to the frailty of the healthcare system in DRC. Part of the DRC’s challenges from a healthcare point of view can be attributed to the poor road network and insufficient logistical resources [4]. These include bottlenecks in the transportation of samples from remote areas to the National Institute of Biomedical Research, the preliminary testing laboratory of the country located in Kinshasa [1]. Another pressing challenge to DRC is the inadequacy of the number of healthcare workers with a ratio of 0.28 physicians per 10 000 population, which is considerably lower than the requisite target of 22.8 professional healthcare workers per 10 000 [1].

The healthcare system capacity of the DRC also struggles to mitigate the impact of the ongoing pandemic due to war and the limited number of testing centres (ie, present only in the towns of Kinshasa, Matadi, Lubumbashi, Goma, Kolwezi and Mbandaka out of the 26 provinces) [4, 5]. For example, the healthcare system logs daily testing of only 900 people out of over 100 million population [4, 5].

In a population of over 90 million people, only 306 299 COVID-19 tests have been conducted among its people [5]. Added to this burden is the lack of medical equipment and PPE, diagnostic devices, poor hygiene and scarcity of clean water, making Congolese inhabitants more vulnerable to waterborne diseases and COVID-19 [1, 5].

On the other hand, the DRC has been recorded as one of the poverty-stricken countries globally, with over 70% of the individuals living in poverty, and COVID-19 has worsened this situation further as the majority lost their jobs. Aside from economic impact, the issues due to low COVID-19 monitoring and surveillance result in standard reporting and inaccurate information [1, 5]. Adding to these complexities, reported insurgencies are considered a violation of human rights. These include slaughtering, displacing individuals and marauding houses, including healthcare centres, although such activity has existed for decades. Amid the pandemic, healthcare workers are not spared from this incident, which disrupts their capacity to respond to the pandemic [1, 2, 5].

Meanwhile, on 8 September 2021, the African section of the WHO announced a death-dealing epidemic of meningitis in the northeastern province of the DRC, in which higher than 260 conjectured cases and 129 mortalities have been communicated; there has been a high case:victim ratio of 50% according to the United Nations health agency [3, 5]. Meningitis is a lethal infection that can be managed with antibiotics and supportive treatments in intensive care units in more severe cases. In similitude to COVID-19, meningitis is transmitted through droplets of respiratory or throat secretions from infected people. Close and prolonged contact or living in close quarters with an infected person enhances the spread of the disease. Most prone individuals to this disease are babies, children and young people; however, people of all ages can contract the condition [3].

More than 100 victims of this disease are being treated at home and in health centres in Banalia, the community affected by the epidemic, according to the WHO [3–5]. The African meningitis belt is the most unprotected and vulnerable to recurrent meningococcal disease outbreaks. The DRC is one of the countries in the African meningitis belt under group 3 of countries with low epidemic risk but high disease burden [4]. History revealed that meningitis outbreaks have happened in several DRC provinces. In 2009, an outbreak in the Kisangani region infected 214 people. It caused 15 deaths, leading to a case fatality ratio of 8%, while the 2021 meningitis outbreak has a 50% fatality risk [6]. According to research conducted between 2000 and 2018, about 118 378 cases were reported by the Ministry of Health in DRC, with a case fatality risk of 11.5% across the 515 health zones [6] The incidence of cases is pronounced in the north and southeast of the country and the provincial city of Kinshasa [6].

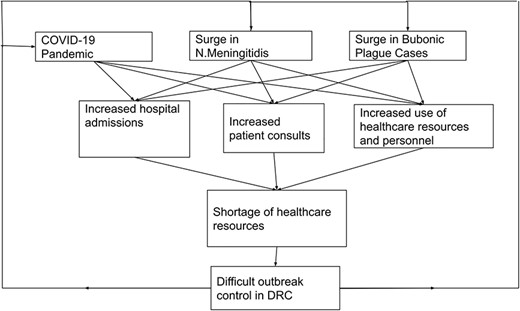

Impact of bubonic plague and meningitis outbreaks amidst the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare provision in DRC. Original figure drawn by the authors. DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo.

In the African meningitis belt, bacterial meningitis incidence is often seasonal, with peaks during the dry season, which then subsides with the onset of the rainy season [6]. However, the dynamics seem to be changing following the recent outbreak in DRC in September 2021 [6]. Even with vaccination, bacterial meningitis remains a significant source of morbidity and mortality among populations in sub-Saharan Africa [6].

Recently, another outbreak affected the country, accentuating the public health crisis in the country. In August 2021, UNICEF announced a resurgence of bubonic plague in Ituri province in the eastern DRC [6]. This bubonic plague or black death is an infectious disease caused by Yersinia pestis bacteria often found in small mammals and fleas. Such bubonic outbreaks are often due to poor sanitation and hygiene practices which attract rats carrying fleas, searching for food. Although the disease can be fatal, it is easily treatable with antibiotics [6]. The Ituri region of DRC, like other African countries, like Madagascar, Mozambique, Uganda and Tanzania, are the only countries where bubonic cases are frequently reported globally [6, 7].

According to UNICEF, the current outbreak seems to be different from previous occurrences because both the bubonic plague and the highly virulent pneumonic form of plague (ie, transmitted from person to person through the air) have been reported in areas that were previously considered free of the disease [6].

The coexistence of outbreaks of these two diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic is a serious threat to the country’s health system and can increase the poor state of the DRC public health system. Compared with the meningitis outbreak and the bubonic plague, it is likely that most of the resources and facilities have been targeted towards dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic due to its worldwide focus on dealing. Thus, individuals infected by either of the former two diseases may be faced with a lack of healthcare attention, which may lead to an increase in cases as many individuals may turn to self-treatment or may ignore their symptoms and continue to integrate themselves into their communities. Even more, the state of current resource shortage and limited facilities means that the vicious cycle of increasing cases and reduced resources for all three diseases may occur. The situation is highly worrying, particularly in rural areas where the pandemic has further hampered limited healthcare access. Lack of funding and distance from health facilities can delay access to healthcare and increase the mortality rate of the three diseases. In addition, the coexistence of these three diseases can lead to misdiagnosis due to overlapping symptoms and simultaneous coinfection, which is potentially fatal, as the fatality rate of plague, for example, can reach 100% without proper treatment (Figure 1) [3, 7].

Recommendations

With the unprecedented burden brought by COVID-19 alongside other pandemics in DRC and the African region, salient action points within the health system are recommended. First, there is a need to scale up efforts in addressing COVID-19, such as ramping up vaccination through effective cold chain and logistics and demand generation to use available supplies efficiently.

In addition, timely pandemic response on existing pandemics such as meningitis and bubonic plague is paramount. While the healthcare system aims to address the pandemic response needs, prevention efforts such as risk communication, health promotion and education, and community mobilisation should also be strengthened in parallel. For this, the government needs to reallocate more funds to the healthcare sector to improve epidemiological and entomological disease surveillance and control programmes focused on eradicating vectors and detecting, isolating, and treating suspected and confirmed cases of both diseases to prevent and contain further outbreaks.

Furthermore, in addition to improving early diagnosis, it is necessary to increase awareness of prevention programmes among the population and to disseminate correct information about warning symptoms and infection control through campaigns and social media. It is also required to promote education programmes focused on healthcare workers’ training to improve clinical management and to establish more efficient protocols to address each disease. Telemedicine services also play an essential role in locations with difficult access or a lack of trained healthcare workers. They can be implemented primarily among those communities with greater risk of the resurgence of new cases. In those communities, it is also mandatory to improve vaccination strategies against COVID-19 and meningitis and enhance basic sanitation measures for pest control.

Therefore, both response and prevention interventions require significant investments in human resources for health; infrastructures; medical technologies such as diagnostics, drugs and devices; and service delivery, among others. Thus, with the support across different sectors, primarily the government at the forefront, the impact of these three pandemics can be largely mitigated.

Conclusion

The coexistence of three pandemics in DRC calls for an urgent need for the WHO and other international organisations to rescue DRC, a need to revitalise the healthcare system to manage these three plagues and support in scaling up efforts on COVID-19 vaccination.

Contributors

All authors substantially contributed to the preparation of this article. All authors revised and approved the final draft.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None declared.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

et al