-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tomas Ferreira, Escalating competition in NHS: implications for healthcare quality and workforce sustainability, Postgraduate Medical Journal, Volume 100, Issue 1184, June 2024, Pages 361–365, https://doi.org/10.1093/postmj/qgad131

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) faces escalating competition ratios for specialty training positions, with application rates dramatically outpacing the growth in available posts. This trend contributes to systemic bottlenecks and challenges traditional career progression pathways within medicine. In this evolving landscape, the once-certain career progression within medicine is now increasingly uncertain. This commentary explores the complex dynamics of increased medical school admissions against stagnant specialty training placements and the broader strategic implications for workforce planning within the NHS. It critically evaluates the implications of current funding policies, which seem to prioritise an expansion of nondoctor healthcare roles over the development of specialist training, raising concerns about the long-term patient care quality and safety. Key recommendations include a reassessment of medical education expansion, a review of funding allocation, increased support for specialty training, and government accountability for healthcare workforce planning. The urgent need for strategic policy reform is underscored to ensure that NHS can sustain a high-quality, specialist-led healthcare provision in the face of rising competition and workforce pressures

Background and context

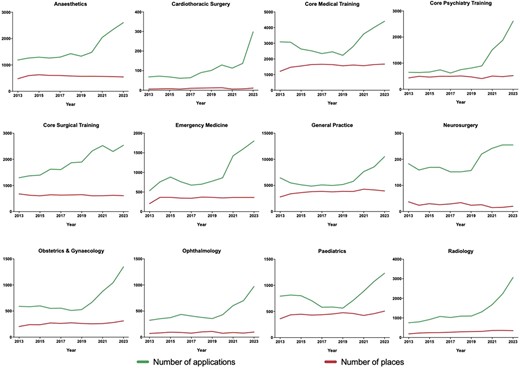

In recent years, competition for specialty training positions in UK’s National Health Service (NHS) has surged. In 2016, there were 20 044 applications for 10 671 posts, with a ratio of 1.88 applications per post. By 2023, this ratio had risen to 3.37, with applications increasing by 249%, while training places only grew by 183%. Some specialties, already renowned for being competitive, such as neurosurgery, have seen increases from in competition ratios from 6.50 in 2016 to 12.75 in 2023. Meanwhile, even in specialties where the demand for services is exceedingly high, such as general practice, competition has intensified, with the ratio rising from 1.28 to 2.67 over the same period (Fig. 1) [1].

Comparative analysis of specialty training applications and available positions (2013–23); this figure comprises 12 individual graphs representing a selection of specialties at ST1/CT1 level within the NHS; each graph delineates the annual trend of applications alongside the number of training positions available per specialty from 2013 to 2023; two lines are plotted in each graph: one indicating the ‘number of applications’ and the other, the ‘number of available positions’, for a particular specialty; this visual representation highlights the escalating competition across various specialties over the depicted years.

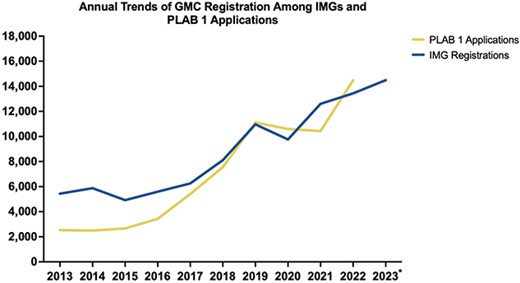

One critical development potentially exacerbating this competition is the removal of the Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT) in January 2021 [2]. This significant policy change has led to an increase in the number of international medical graduates (IMGs) seeking NHS specialty training roles [3–8]. It is noteworthy that the UK, in contrast to the majority of other countries, does not prioritise its own graduates for these positions. Instead, it treats applications from IMGs and UK-trained graduates equally. This approach, and the absence of this test means that competition for these positions will likely continue to rise. Figure 2 demonstrates how the number of PLAB Step 1 applications and IMG applications to the General Medical Council (GMC) has changed over the years. IMGs, while being invaluable contributors to the NHS, further intensify the competition landscape. This increase in competition for specialty training places occurs against the backdrop of the UK’s position as the country with the lowest doctor-to-population ratio among European countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and government efforts to address this by increasing medical school admissions are also set to also worsen competition [9–11]. In this evolving landscape, the once-certain career progression within medicine is now increasingly uncertain. This commentary seeks to explore the causes and consequences of this issue, offering recommendations to address it and ensure the sustainability of the NHS.

Annual trends of GMC registration among IMGs and PLAB 1 applications (2013–23); the graph illustrates the annual counts of IMGs granted GMC registration alongside the number of PLAB 1 applications; PLAB 1 application data are not yet available for 2023; the IMG registration data were acquired through a freedom of information request to the GMC, referenced as 23-077R; the legends ‘IMG registrations’ and ‘PLAB 1 Applications’ correspond to the two datasets depicted; *for the year 2023, the registration data are represented up to 30 September 2023.

Unchanged training spaces amidst increased medical school admissions

The persistent stagnation in Health Education England’s (HEE’s) funding for training places is exacerbating the competition ratios in specialty training. Despite an increase in medical school admissions, and further plans to double medical school places, the restricted expansion of specialty training positions has created bottlenecks at critical transition points within medical careers, including from medical school to Foundation Year 1 [12], from Foundation Year 2 (F2) to specialty training [1], and to then securing a consultant role [13, 14]. This issue requires immediate attention, as it not only impedes the career progression of medical graduates but also raises questions about the quality of patient care.

The creation of artificial bottlenecks in medicine, particularly through an increased supply of medical graduates without a corresponding increase in training positions, is a growing concern. While the NHS is already facing a retention crisis, as substantiated by surveys conducted by the British Medical Association (BMA) and the Ascertaining the career Intentions of UK Medical Students (AIMS) study, these bottlenecks could potentially exacerbate the situation, leading to an even greater exodus of doctors from the NHS. For instance, in 2021, ~10 000 doctors, nearly 10% of the workforce, relinquished their medical licences [15, 16]. BMA’s surveys indicates that 44% of senior doctors are contemplating an NHS departure [17] and that 40% of ‘junior’ doctors are considering leaving, with a third of them considering employment abroad [18]. Alarmingly, a recent study of nearly 11 000 medical students in the UK uncovered that ~35% of students intend to leave the NHS within 2 years of graduating, even before fully entering the profession [19]. This existing crisis of retention could be further aggravated by the heightened competition, leading to a potentially more significant loss of medical personnel.

The impact of doubling medical school places is a matter of concern. While increasing admissions, it remains unfeasible to equally double the number of specialty training positions required to accommodate these graduates without substantial increases in theatre and bed capacity. Consequently, this could lead to a surplus of doctors, particularly post-F2 doctors, who may find limited opportunities for training. International mobility for these doctors may soon be hindered due to a saturated market in anglosphere countries and a lack of recognition for the proposed new, unconventional medical training programmes [10, 11]. Moreover, there is the question of whether the increase of medical school places is likely to proportionately improve NHS staffing in lieu of the current retention crisis if other issues are not addressed [19].

The government’s role in these developments appears to involve efforts to control the labour market and reduce costs. This strategy may create a perpetual ‘F3 doctor’ who is internationally immobile and commands significantly lower remunerative rates compared to their counterparts progressing through specialty training to become consultants. Additionally, there are concerns that these developments may lead to a market scenario with reduced locum shift availability, leaving doctors unable to obtain a training place with only clinical fellowship roles as the alternative which offer significantly lower remuneration. Ultimately, this strategy stands to benefit the government by ensuring a larger number of doctors at a lower cost, but it raises concerns about the potential consequences for healthcare quality and the financial well-being of these doctors.

Funding diversion to Physician Associate and Anaesthesia Associate programmes

While HEE has reduced or stagnated funding for specialist training roles for doctors, it has paradoxically introduced and increased funding for nondoctor positions such as Physician Associates (PAs) and Anaesthesia Associates (AAs) [20]. This reallocation of resources comes at a time when the number of training places for essential roles, such as anaesthetists and surgeons, is in decline—a counterintuitive strategy, given the significant patient backlogs for surgical interventions [21]. In 2016, HEE funded 603 anaesthetics training places, which has now decreased to only 545 in 2023. Similarly, the number of training places for surgeons has dropped from 642 to 609 during the same period [1].

Compounding the situation, the recently published NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (LTWP) has outlined ambitious plans to not only increase the number of PAs and AAs but to also expand their scope of practice [10, 11]. This expansion has sparked intense debate within the medical community, with members from various Royal Colleges calling for Extraordinary General Meetings to voice their opposition [22, 23]. The primary concern revolves around the adequacy of the training and education of these associates and their growing scope of practice amid concerns over the sustainability of healthcare quality and the strategic direction of workforce planning within the NHS.

Moreover, amidst several national reports of misconduct, unlawful proceedings, and high-profile avoidable patient fatalities involving nondoctor healthcare professionals, the debate over the role of PAs and AAs has gained even more urgency [24–31]. These incidents have cast a shadow over the competence and preparedness of nondoctor healthcare providers for their current scope of practise, leading to questions about whether they should undertake further expanded roles as outlined in the NHS LTWP.

Section 3: implications and recommendations

The implications of the rising competition in NHS specialties and the potential workforce restructuring are profound and require careful consideration.

(1) The increasing competition and workforce restructuring (changes to doctor:associate ratios through diversion of funds from specialty posts to associate roles) have the potential to impact the quality of healthcare within the NHS. This includes increased risks to patient safety, prolonged waiting times, and reduced access to specialist care.

(2) Further, a shift towards favouring nondoctor roles may lead to disparities in healthcare. Those who can afford private care may receive doctor-led services, while others may receive care from nondoctor healthcare professionals in the NHS. Ensuring equitable access to quality healthcare for all patients is imperative.

(3) The elevated competition and pressure on doctors may result in increased stress levels and burnout. This not only affects the well-being and satisfaction of doctors but also compromises the quality of care they provide. Addressing workforce burnout is essential to ensure the retention of skilled professionals and mitigating current attrition trends. Such dissatisfaction may further increase the number of doctors considering abandoning the NHS. It is imperative to address these issues comprehensively to retain skilled medical practitioners and to ensure the NHS’s long-term viability.

(4) The shortage of specialists caused by an increase in unspecialised doctors can slow the progress in medical science and technology. Doctors play a critical role in advancing medical knowledge. Therefore, addressing the shortage is vital to foster innovation and research within the healthcare sector.

To address these challenges, several recommendations are proposed:

(1) Reassess the expansion of medical school places: It is prudent to reconsider doubling the number of medical school students as planned. The system is likely to struggle to accommodate this influx, leading to a surplus of doctors in certain stages of their careers.

(2) Funding allocation: There must be a balanced allocation of funding. This should include expanding both medical school admissions and specialty training places in proportion to the rising number of medical graduates. Consultant posts must also be proportionately increased to avoid later career stage bottlenecks. This approach can alleviate competition ratios and ensure a smoother transition from medical school to specialty training and maintain the quality of patient care.

(3) Support for specialty training: Increased support for specialty training programmes is essential. This includes expanding theatre capacity, addressing the shortage of hospital beds, and ensuring a proportional increase in allied healthcare professionals and facilities. These measures are essential to accommodate the growing number of specialty trainees and to provide the necessary infrastructure to meet their training requirements effectively.

(4) Assessment of training needs: Regularly assess the healthcare needs of the population and align training programmes with these needs. This ensures that training places are allocated to specialties where there is a genuine demand for services, thereby reducing excessive workload and mitigating burnout among healthcare professionals. Additionally, this process can facilitate the reallocation of funding from specialties experiencing a decline in service demand to specialties with high demand, allowing for the expansion of training opportunities in those high-demand specialties.

(5) Government accountability: The critical role of the government in shaping these developments must not be overlooked. Increased transparency and accountability in healthcare workforce planning are needed. Policies should prioritise the quality of care and the well-being of healthcare professionals over cost-cutting measures. Patient and doctors should be actively involved in policymaking, both senior doctors and those in training.

Conclusion

Existing bottlenecks in the NHS’s specialty training system have worsened, and future prospects look even bleaker with the government’s intention to double medical school admissions and with the removal of the RLMT. This escalation in competition for training positions threatens both the career progression of medical graduates and the quality of patient care. The diversion of funds to nondoctor roles also raises important concerns about expertise and patient safety. In summary, addressing these challenges and embracing strategic workforce planning is critical to preserve the integrity and effectiveness of the NHS in the face of escalating competition and workforce shortages.

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.