-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Munkhtsetseg Tsednee, Shun-Chung Yang, Der-Chuen Lee, Kuo-Chen Yeh, Root-Secreted Nicotianamine from Arabidopsis halleri Facilitates Zinc Hypertolerance by Regulating Zinc Bioavailability , Plant Physiology, Volume 166, Issue 2, October 2014, Pages 839–852, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.241224

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hyperaccumulators tolerate and accumulate extraordinarily high concentrations of heavy metals. Content of the metal chelator nicotianamine (NA) in the root of zinc hyperaccumulator Arabidopsis halleri is elevated compared with nonhyperaccumulators, a trait that is considered to be one of the markers of a hyperaccumulator. Using metabolite-profiling analysis of root secretions, we found that excess zinc treatment induced secretion of NA in A. halleri roots compared with the nonhyperaccumulator Arabidopsis thaliana. Metal speciation analysis further revealed that the secreted NA forms a stable complex with Zn(II). Supplying NA to a nonhyperaccumulator species markedly increased plant zinc tolerance by decreasing zinc uptake. Therefore, NA secretion from A. halleri roots facilitates zinc hypertolerance through forming a Zn(II)-NA complex outside the roots to achieve a coordinated zinc uptake rate into roots. Secretion of NA was also found to be responsible for the maintenance of iron homeostasis under excess zinc. Together our results reveal root-secretion mechanisms associated with hypertolerance and hyperaccumulation.

Micronutrients such as zinc and iron are essential to living organisms. They function as structural constituents, catalytic cofactors, and activators in enzymes and proteins (Marschner, 1995; Hänsch and Mendel, 2009). However, these nutrients become extremely toxic when present in excess. The concentration of zinc in shoots normally falls in the range of 50 to 100 μg g−1 dry biomass (Marschner, 1995). When shoot zinc concentrations exceed 300 μg g−1 dry biomass, zinc toxicity in plants results in leaf chlorosis, altered physiology, and inhibited plant growth. Because plants obtain nutrients from soil through roots, overaccumulation and toxicity of these minerals in plants is mainly caused by their excessive presence in soil. Adaptation to soil characteristics is therefore critical for plant survival, and is associated with the ability to acquire resources from the environment (Baxter and Dilkes, 2012).

Plants that hyperaccumulate metals grow endemically in metal-rich or metal-contaminated soils and exhibit extraordinarily high metal tolerance (Baker and Brooks, 1989; Krämer, 2010). Naturally selected, these hyperaccumulators, which are found in over 400 plant taxa, possess the unique ability to accumulate extremely high concentrations of certain metals in aboveground tissue with remarkable metal tolerance (Krämer, 2010). Gaining understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying complex metal homeostasis networks in hypertolerant and hyperaccumulating species is important from several different perspectives, including shedding light on how genetic diversity is shaped by soils (Horton et al., 2012), investigating the potential use of plants for phytoextraction or phytomining (Chaney et al., 1997; Pilon-Smits, 2005), and, notably, for probing the possibility of biofortification to improve nutrient efficiency in crops (Broadley et al., 2007; Palmgren et al., 2008).

Zinc hyperaccumulators, which have shoot zinc concentrations of more than 10,000 μg g−1 dry biomass (nearly 100-fold higher than normal plants), have been reported in 15 plant taxa (Baker and Brooks, 1989; Krämer, 2010). Some zinc hyperaccumulators are also known to hyperaccumulate cadmium (Verbruggen et al., 2009). To uncover the molecular basis of the unique physiology associated with excess zinc, over the past decade valuable studies have been conducted in two zinc-hyperaccumulating plants: Arabidopsis halleri (Hanikenne and Nouet, 2011) and Noccaea caerulescens (formerly Thlaspi caerulescens; Milner and Kochian, 2008), both of which have a close phylogenetic relationship to Arabidopsis thaliana (Krämer, 2010).

A. halleri hyperaccumulates zinc from both metal-contaminated and noncontaminated soils (Bert et al., 2000). The candidate genes responsible for zinc hypertolerance and hyperaccumulation in A. halleri have been identified by comparative transcriptional profiling of A. halleri and nonhyperaccumulator A. thaliana (Becher et al., 2004; Weber et al., 2004; Chiang et al., 2006; Talke et al., 2006). The constitutively highly expressed genes associated with metal homeostasis in A. halleri encode a nicotianamine (NA) synthase and putative zinc transporters such as ZINC REGULATED TRANSPORTER, IRON REGULATED TRANSPORTER (IRT)-like proteins (ZIPs), A. halleri HEAVY METAL ATPase4 (AhHMA4), A. halleri METAL TOLERANCE PROTEIN1 (AhMTP1), and natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins (NRAMPs; Krämer et al., 2007; Hanikenne and Nouet, 2011). Detailed studies further demonstrated that the increased zinc xylem loading is associated with AhHMA4 (Hanikenne et al., 2008) and efficient zinc sequestration in leaf vacuoles involves AhMTP1 (Dräger et al., 2004; Shahzad et al., 2010). Contributions of NA to plant metal homeostasis must be huge because NA is detected ubiquitously in all plant species and NA can bind several transition metals with high affinity (Takahashi et al., 2003; Rellán-Alvarez et al., 2008; Curie et al., 2009). Elevated NA content in roots is a common phenomenon in different A. halleri individuals regardless of soil zinc concentrations (Deinlein et al., 2012). The NA content in A. halleri roots was recently demonstrated to play a key role in zinc hyperaccumulation by facilitating zinc movement from root to shoot in the form of a Zn(II)-NA complex (Deinlein et al., 2012). Although these genetic studies of A. halleri have expanded understanding of plant adaptation mechanisms in terms of metal translocation and metal sequestration in plants, the primary interactions of these specific traits with surrounding soil environments to regulate the metal bioavailability are still not understood.

Plants regulate the availability of nutrients in the rhizosphere through releasing metabolites from the roots (Dakora and Phillips, 2002; Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012). Up to 10% of photosynthetically fixed carbons are known to be secreted from the roots (Johansson, 1992; Gleba et al., 1999), and the rhizosphere, as the primary interface of plant and soil, has very different chemical and physical characteristics from bulk soil. Availability and/or mobility of metals in soil depends mostly on metal speciation in soil solution, rather than total soil concentrations (Stephan et al., 2008). Large numbers of root-secreted metabolites may change nutrient bioavailability through changing the rhizosphere pH or directly binding to minerals (Gorban et al., 2000; Badri and Vivanco, 2009). In metal-polluted environments, root-secreted metabolites are known to protect plants from exposure to heavy metals at high concentrations by inhibiting the uptake of toxic metals through an excluder strategy that restricts soil metal availability via complex formation (Kochian et al., 2004; Lin and Aarts, 2012). One common mechanism is the root secretion of organic acids such as oxalate, malate, and citrate to prevent the uptake of toxic metals such as aluminum (Kochian et al., 2004), cadmium (Pinto et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2011), and lead into plants (Yang et al., 2000).

Interestingly, studies of zinc bioavailability in different types of contaminated soils have shown that zinc is more mobile and potentially more bioavailable in contaminated soils than other metals such as copper, nickel, and cadmium (Ma and Rao, 1997). In soil, zinc bioavailability can be determined by Zn2+ (Stephan et al., 2008). In acidic soil, Zn2+ is soluble and mobile like free aluminum (Al3+) and free manganese (Mn2+) and is thus considered as one of the most common phytotoxic metals (Stephan et al., 2008).

In this study, we analyzed the metabolites secreted from the roots of A. halleri to determine whether any specific secreted compounds play a role in hypertolerance and hyperaccumulation.

RESULTS

Comparative Metabolite Profiling of Root Exudates: A. halleri Secretes NA

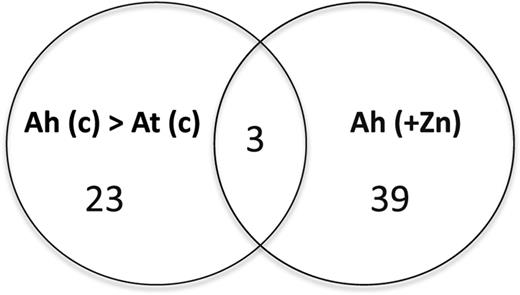

Plants release large numbers of metabolites from their roots into the rhizosphere to regulate nutrient bioavailability (Badri and Vivanco, 2009). To examine whether any specific metabolites secreted from A. halleri roots may be involved in its hypertolerance and hyperaccumulation, we first compared the metabolite profiles of root exudates of hydroponically grown A. halleri and A. thaliana under control conditions. Comparative metabolite profiling of root exudates was obtained with ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with electrospray ionization (ESI) coupled to quadruple time-of-flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) using a hydrophilic column (HILIC) in positive ESI mode. Three independent replicates of root exudate sample were used for the analysis. To obtain the details of differences in the root exudates of the two plants, UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS data sets were further analyzed using orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). S plots of OPLS-DA results can display the biomarkers that differentiate two groups of samples. Based on OPLS-DA S-plot data, 26 metabolites had more than 2-fold higher abundance in root exudates of A. halleri than in A. thaliana (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table S1). Next, we analyzed the root exudates of A. halleri in response to excess zinc treatments. S plots of OPLS-DA were generated using UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS data sets obtained from root exudates of A. halleri treated with control or excess zinc. Forty-two metabolites extracted from the root exudates of A. halleri exhibited more than 2-fold higher abundance under excess zinc conditions (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table S2). We further found that 3 of 26 metabolites with higher abundances in root exudates of A. halleri than in A. thaliana under control conditions were also increased in A. halleri root exudates treated with excess zinc (Supplemental Table S2). Predicted annotations of these three metabolites were obtained from the exact mass measurement analysis of the peaks (Table I).

Venn diagram of metabolites secreted by roots in response to excess zinc. Metabolite profiling of root exudates collected from A. thaliana (At) and A. halleri (Ah) plants was obtained with UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS using an HILIC column in positive ESI mode. Root exudates were collected from the control (c) and excess zinc (+Zn) treatments in triplicate. Metabolite peaks were selected that had normalized intensity more than 2-fold greater in A. halleri exudates than in A. thaliana under the control conditions (Ah > At), and more than 2-fold greater in A. halleri root exudates under excess zinc (additional 100 μm) treatment (Ah) than in A. halleri under control conditions.

Predicted annotations of specific metabolites detected in A. halleri root exudates

Predicted elemental composition of the metabolites was obtained in positive ESI mode. Isotope fit values were obtained with MassLynx software (Waters).

Predicted elemental composition of the metabolites was obtained in positive ESI mode. Isotope fit values were obtained with MassLynx software (Waters).

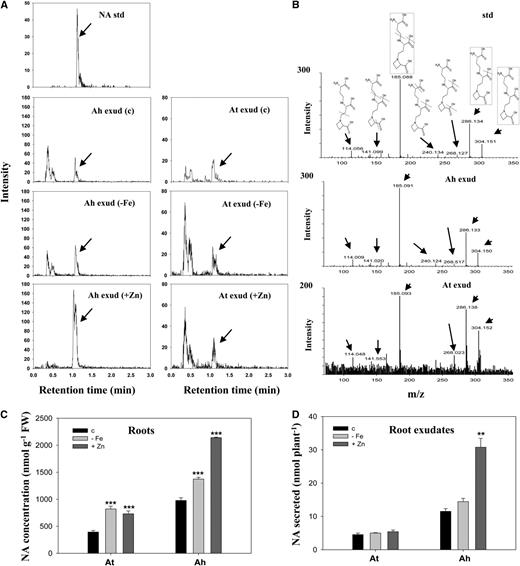

One of these metabolites had a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of 304.150 with predicted elemental composition of C12H22N3O6 (Table I). Interestingly, mass parameters of this compound matched the parameters of NA, a metal-chelating compound. To confirm this peak, we used an NA standard for liquid chromatography (LC)-MS analysis. Using the NA standard and comparing the peak retention time on a chromatographic column (Fig. 2A) and mass fragmentations from tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS; Fig. 2B), we confirmed that this candidate metabolite was NA (Supplemental Table S3). MS/MS analysis of the NA standard further identified another compound from three metabolites detected at an m/z of 286.140 and predicted the elemental composition of C12H20N3O5. This was confirmed to be the mass fragment of the NA peak (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table S3). One more mass fragment of NA at an m/z of 185.093 was also detected under excess zinc (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table S2).

NA in roots and root exudates of A. halleri and A. thaliana. A, NA in root exudates of A. halleri (Ah exud) and A. thaliana (At exud) grown under control (c), iron deficiency (−Fe), and excess zinc (+Zn) conditions was determined using an NA standard (NA std) with UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS. For excess zinc treatments, 10 μm and 100 μm zinc were supplemented into culture solutions of A. thaliana and A. halleri, respectively. B, Tandem mass spectrums (MS/MS) of the identified NA peak in root exudates of A. halleri and A. thaliana are shown compared with the NA standard. The proposed fragmentation pathway of NA is represented with dotted lines. Structures in dotted lines are identified in Table I and Supplemental Table S2. C and D, NA concentrations in roots (C) and root exudates (D) of A. thaliana (At) and A. halleri (Ah) grown hydroponically under the control, iron deficiency, and excess zinc conditions. Seven-day-old hydroponically grown plants were transferred to treatments for 12 d. Data are the mean ± sd of four replicates with three technical repeats. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with the control treatment. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by the Student’s t test. FW, Fresh biomass.

Because NA binds to several metals including iron, we used iron deficiency treatments together with excess zinc for further analysis of the secretions of NA from A. halleri. Of note, NA was detected not only in the root exudates of A. halleri under all treatment conditions, but was also in low abundance in the root exudates of A. thaliana under the same treatments (Fig. 2A). Although the secretion of NA from plant roots is reported here for the first time to our knowledge, NA was previously found in all vascular plants (Kobayashi et al., 2010), including lower plants (Erxleben et al., 2012).

In grasses, NA is a precursor compound of phytosiderophores, which are natural iron-chelating compounds that can be secreted from roots (Ma and Nomoto, 1996). However, unlike phytosiderophores, NA was not previously found to be one of the metabolites secreted from grasses (Takahashi et al., 2003). To confirm this, we examined NA secretion from barley (Hordeum vulgare) roots. In line with previously published reports (Howe et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 2006; Tsednee et al., 2012), we found that NA was not detectable in barley root exudates, but was clearly detectable inside the root (Supplemental Fig. S1). In addition to barley, we also checked NA secretion from other grasses, rice (Oryza sativa), and wheat (Triticum durum), under the same treatments and found no secretion of NA from these grasses (data not shown). We further compared the metabolite profiling in roots and root exudate samples to examine the overall false positive exudation of metabolites from the roots. From this comparative metabolite profiling of roots and exudates, we tried to look for metabolites detected at high levels in roots but not in exudates. There were more than 100 metabolites detected only in roots of A. halleri and A. thaliana, but not in their root exudate samples under different treatments. Two metabolites, glutathione and scopolotein, are shown as representatives of not-secreted and secreted metabolites, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2). The lack of detection of NA in the root exudates of grasses and the results of the metabolite comparison suggested that false positive exudation of metabolites from the damaged roots under the culture conditions was not likely.

A. halleri plants were previously shown to have 2.7- to 6.9-fold higher NA content in their roots than in A. thaliana (Deinlein et al., 2012). In our hydroponic system, NA concentrations in A. halleri roots were 2.5-fold higher than in A. thaliana under the control conditions (Fig. 2C). NA concentrations were elevated to significantly higher levels in both A. halleri and A. thaliana roots under iron deficiency and excess zinc treatments compared with control conditions. NA amounts secreted in root exudates of A. halleri were about 5-fold higher than those secreted from A. thaliana under control conditions. NA secretion by A. halleri was similar under iron deficiency and control conditions; however, it was dramatically higher (2.8-fold) under excess zinc treatment (Fig. 2D). In contrast with A. halleri, NA secretion from A. thaliana remained similar under iron deficiency or excess zinc conditions (Fig. 2D). Under excess zinc treatments, the amount of NA secreted from A. halleri roots was 11.4-fold higher than that from A. thaliana roots. Together, these data indicate that A. halleri secretes the metal-chelator compound NA, and NA secretion is increased under excess zinc. Because these data suggest a possible involvement of NA secretion in response to excess zinc, we were next prompted to address the question of whether NA secretion from A. halleri roots is involved in zinc hyperaccumulation and hypertolerance.

NA Secreted from A. halleri Roots Forms a Stable Complex with Zn(II)

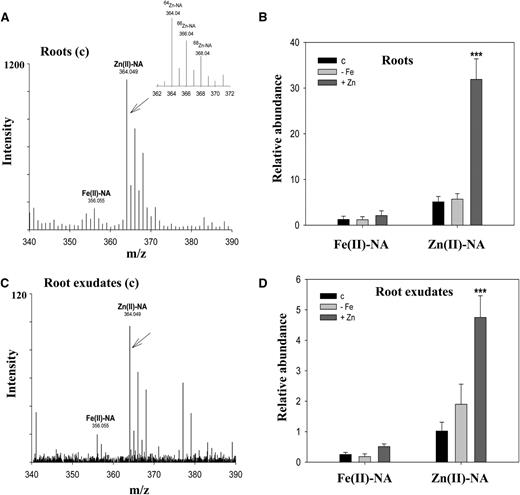

In plants, NA functions as a metal chelator by forming stable complexes with a range of transition metals including iron, zinc, copper, nickel, and cobalt in different pH environments (Rellán-Alvarez et al., 2008). In A. halleri, NA is known to function as a zinc-binding ligand (Trampczynska et al., 2010; Deinlein et al., 2012). To investigate the function of the secreted NA, we first analyzed metal-NA complexes in A. halleri roots and root exudates. LC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS, in negative ESI mode, can identify negatively charged metal-NA complexes and their mass isotopic patterns (Tsednee et al., 2012). For example, an Fe-NA complex was identified with iron isotopic patterns as follows: 54Fe (5.8%), 56Fe (91.7%), 57Fe (2.2%), and 58Fe (0.3%; Rellán-Alvarez et al., 2008; Tsednee et al., 2012). A Zn(II)-NA complex was identified with zinc isotopic patterns of 64Zn (48.6%), 66Zn (27.9%), and 68Zn (18.8%; Rellán-Alvarez et al., 2008). We calculated the theoretical mass and isotopic distributions of the complexes using online software (http://fluorine.ch.man.ac.uk/; University of Manchester).

In A. halleri roots, we detected two metal-NA complexes, Zn(II)-NA and Fe(II)-NA, at 364.049 m/z and 356.055 m/z, respectively (Fig. 3A). To confirm the metal-NA complexes, we used prepared metal-NA complex standards for analysis (Tsednee et al., 2012). The relative abundance of the Zn(II)-NA complex in A. halleri roots was 3- to 15-fold higher than that of the Fe(II)-NA complex under the treatment conditions (Fig. 3B). Consistent with a previous report (Deinlein et al., 2012), our results showed that NA functions primarily as a zinc-binding ligand in A. halleri roots. Two complexes, Zn(II)-NA and Fe(II)-NA, were also observed in the root exudates (Fig. 3C). The relative abundance of the Zn(II)-NA complex was 1.5- to 4.5-fold higher than that of the Fe(II)-NA complex under control, iron deficiency, and excess zinc conditions (Fig. 3D). Because of the lack of a quantification method for the metal-NA complexes, relative abundances are presented. The identifications of metal-NA complexes on chromatograms are also shown (Supplemental Fig. S3). We did not detect the Fe(III)-NA complex. This might be because it has lower stability than Fe(II)-NA in the condition (von Wiren et al., 1999; Tsednee et al., 2012).

Secreted NA forms stable complexes with Zn(II). A, Metal-NA speciation analysis in A. halleri roots. B, Relative abundances of the identified complexes in A. halleri roots were obtained with normalized peak areas of the complexes using an internal control. C, Root exudates collected from the control (c) treatment revealed Zn(II)-NA and Fe(II)-NA complexes at 364.049 and 356.055 m/z, respectively, in UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS in ESI negative mode. D, Relative abundances of the identified complexes in A. halleri root exudates were obtained with normalized peak areas of the complexes using an internal control. Leu enkephalin (0.2 ppm) was used as an internal control. Samples were collected from the control (c), iron deficiency (−Fe), and excess zinc (+Zn) treatments for 12 d. Data are the mean ± sd of four replicates with three technical repeats. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with the control treatment. ***P < 0.001 by the Student’s t test.

We further tested the stability of the Zn(II)-NA complex in root exudates by adding excess amounts of ferrous and ferric iron. Neither Fe(II) nor Fe(III) changed the relative abundances of Zn(II)-NA complexes in root exudates (Supplemental Fig. S4). The abundance of the Zn(II)-NA complex was increased only when excess zinc ions were added into exudates. The data therefore indicate that the Zn(II)-NA complex is highly stable in exudate samples. An in vitro metal-NA complex analysis previously showed that the Zn(II)-NA complex is most stable in the pH range from 5.5 to 8.5 (Rellán-Alvarez et al., 2008). Because we collected root exudates in water, the pH values of the root exudates were in the range of 6.0 to 6.7. This pH range occurs commonly in natural soil conditions including zinc-contaminated soils (Gorban et al., 2000; Stephan et al., 2008). It is therefore possible that the Zn(II)-NA complex is also stable in the rhizosphere. Together, these data suggest that NA secreted from A. halleri roots forms a stable complex with Zn(II) and acts as a zinc-binding ligand.

NA Secretion Is Induced by Excess Zinc

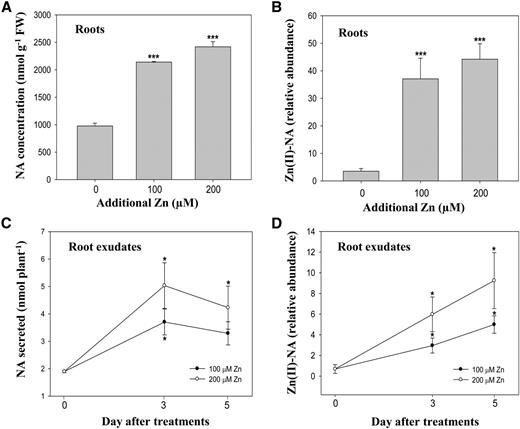

Because NA secretion was increased under excess zinc, we next wanted to confirm the regulation of NA secretion in A. halleri. For this, NA in roots and root exudates of A. halleri was quantified under different concentrations of excess zinc. When treated with 100 μm excess zinc, the NA concentrations in A. halleri roots increased 2.3-fold. There was no further significant increase with 200 μm excess zinc treatments because NA concentration in these plants increased only 2.5-fold compared with control conditions (Fig. 4A). The relative abundances of Zn(II)-NA complexes in A. halleri roots showed similar patterns to the concentrations of free NA under excess zinc treatments. The abundance of the Zn(II)-NA complex increased significantly under 100 μm excess zinc treatment; however, the relative abundance was not further increased under 200 μm excess zinc conditions (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, NA amounts in A. halleri root exudates increased significantly according to excess zinc concentrations showing 2-fold and 3-fold increases under 100 μm and 200 μm excess zinc treatments, respectively, after a 3-d treatment (Fig. 4C). The NA amounts in root exudates were not increased further after treatment for 5 d. However, the relative abundances of Zn(II)-NA complexes in root exudates showed a consistent increase with different zinc concentrations and the number of excess zinc treatment days (Fig. 4D). Together, these data suggest that NA secretion and Zn(II)-NA complex formation increase in response to excess zinc presence.

A. halleri roots secrete NA in response to excess zinc. A, NA concentrations in A. halleri roots were determined under different concentrations of excess zinc supplements treated for 7 d. B and D, Relative abundances of Zn(II)-NA complex in A. halleri roots (B) and root exudates (D) under different excess zinc treatments (100 and 200 μm Zn) are shown in normalized peak areas of the complexes to an internal control. C, Secreted NA in A. halleri root exudates collected under 100 μm or 200 μm of supplied excess zinc after 3- and 5-d treatments. Data are the mean ± sd of four replicates with three technical repeats; each replicate of roots and root exudates was a pool of four plants and combined exudates of three culture containers. Leu enkephalin (0.2 ppm) was used as an internal control. The asterisks denote significant differences compared with the control treatment. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 by the Student’s t test. FW, fresh biomass.

Based on the NA detection in root exudates, we further tried to estimate the concentration of secreted NA in the rhizosphere of A. halleri (Supplemental Fig. S5). Because the volume of the rhizosphere is smaller than the volume of the collected exudates, the concentration of NA near the root surface is expected to be higher than in the root exudates. Assuming that the volume of the rhizosphere is about the same as the root volume, the concentration of NA is restrained in the 40 μm range. The stoichiometry of NA and zinc complex formation in the rhizosphere or culture conditions is also of interest to estimate the presence of the Zn(II)-NA complex and free zinc in the environment. Interestingly, the data showed that Zn(II)-NA complex formation could also be increased according to the presence of Zn(II) ions (Supplemental Fig. S6).

We checked the expression of NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE (NAS) genes in A. halleri roots and leaves under different concentrations of excess zinc (Supplemental Fig. S7). The results showed slight up-regulation of NAS2 in A. halleri roots according to excess zinc concentrations. This line of evidence therefore indicates increased demand for NA in A. halleri roots under high zinc conditions.

Exogenous NA Decreases Zinc Uptake

Apoplastic metal complex formation has dual roles in increasing or decreasing nutrient acquisition (Gorban et al., 2000). Zinc uptake into A. halleri roots was previously reported to be as free Zn2+ ions through ZIP transporters (Aucour et al., 2011). Higher expression of ZIPs in A. halleri roots relative to A. thaliana was also suggested to be a part of a zinc uptake control mechanism (Shanmugam et al., 2011, 2013). We therefore predicted that the Zn(II)-NA complex on the A. halleri root surface might not be taken into plants. To investigate this possibility, we used A. thaliana because its NA secretion remained at a stable trace level as well as the zinc stable isotope 67Zn to further clarify the effects of root-secreted NA and Zn(II)-NA complex formation on the uptake of zinc. For this purpose, 15-d-old hydroponically grown A. thaliana plants were transferred to culture solution containing different concentrations of excess 67Zn with or without exogenous NA. Root and shoot samples were collected after 24 h. The effect of exogenous NA on short-term uptake of stable isotope 67Zn in A. thaliana was further examined using high-resolution inductively coupled plasma (HR-ICP)-MS by quantifying the 67Zn in root and shoot tissues.

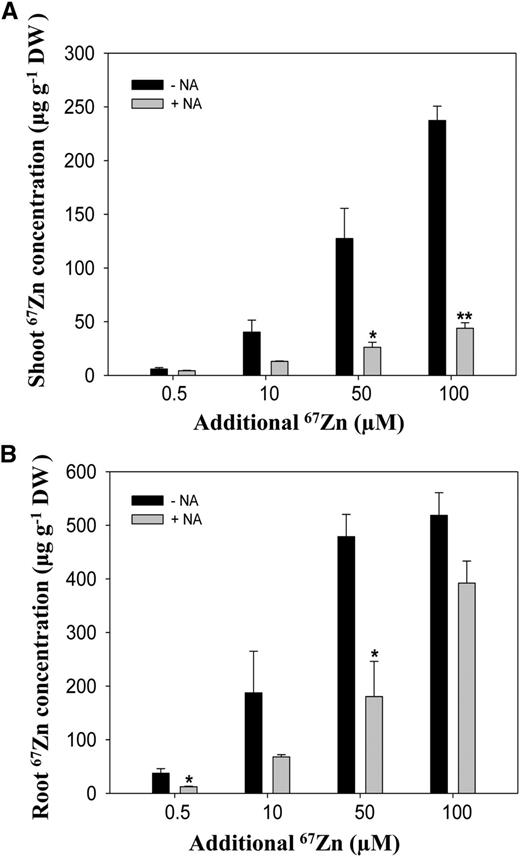

HR-ICP-MS data showed that uptake and translocation of 67Zn were decreased significantly with additional supply of NA to the culture solution (Fig. 5). When 50 μm NA was added exogenously, the concentrations of 67Zn in A. thaliana roots decreased significantly by 60% to 20% in both NA-supplied control and excess zinc treatments. The concentrations of 67Zn in shoots consequently showed significant decreases (50%–90%) in samples treated with exogenous NA. These results indicate that the uptake of zinc in A. thaliana decreases with NA presence outside the roots. This evidence further implies that the Zn(II)-NA complex cannot be taken in by the plants or slows down the zinc uptake into A. thaliana roots.

Exogenous supply of NA and zinc uptake. A and B, The concentrations of 67Zn, a stable isotope of zinc, in shoots (A) and roots (B) of A. thaliana grown hydroponically under excess zinc treatments at the indicated concentrations supplied with 50 μm NA (+NA) or without NA (−NA) were determined using HR-ICP-MS. The samples were collected after treatment for 24 h. Data are the mean ± sd of four replicates with four pooled plants each. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with no NA treatment. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by the Student’s t test. DW, Dry biomass.

Taken together, these results suggest that the presence of secreted NA reduces the zinc uptake rate through regulating zinc bioavailability. In support of this interpretation, our data showed that A. halleri did not accumulate more zinc than A. thaliana in the same excess zinc concentrations (Shanmugam et al., 2011; Supplemental Fig. S8)

Supplying NA Confers Tolerance to Excess Zinc in A. thaliana

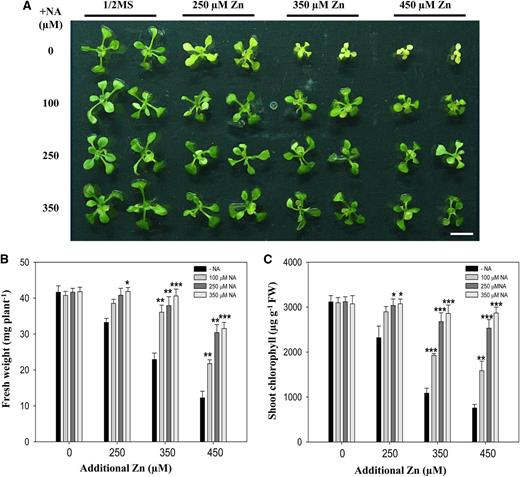

Tolerance to excess metal exposure in plants is a complex process that consists of controlled uptake, translocation, and sequestration of metals (Clemens, 2001; Lin and Aarts, 2012). The responses to certain metal stresses inside the plant could possibly be different from their apoplastic regulation (Marschner, 1995; Gorban et al., 2000). Therefore, we next specifically tested whether the exogenous NA could affect zinc tolerance. For this experiment, we used A. thaliana, which has both relatively low endogenous and secreted NA, to reduce interference from existing NA both inside and outside plants. To test the effect of root-secreted NA on zinc tolerance, we grew A. thaliana seedlings in the presence of NA under excess zinc conditions for 10 d. An exogenous supply of NA resulted in dramatically increased zinc tolerance in A. thaliana (Fig. 6). The phenotype (Fig. 6A) was confirmed by plant biomass and shoot chlorophyll content. Treatment with different concentrations of excess zinc decreased plant biomass in the range of 29% to 80% compared with that of control plants. However, the reduced plant biomass as a result of excess zinc treatment was significantly ameliorated by NA supplementation (Fig. 6B). Consistent with this result, loss of shoot chlorophyll content also remained significantly lower in plants supplied with NA compared with plants without NA treatment under excess zinc conditions (Fig. 6C). Zinc tolerance in A. thaliana was further increased significantly with an increase in the supply of NA. In summary, these data demonstrate that an exogenous NA supply results in greatly increased zinc tolerance in A. thaliana.

Supplying NA affects zinc tolerance in A. thaliana. A, Phenotypes of A. thaliana plants grown under 250, 350, or 450 μm excess zinc treatments supplemented with the indicated concentrations of exogenous NA. Four-day-old A. thaliana seedlings grown in one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium were treated for 10 d. Bar = 1 cm. B and C, Fresh biomass (B) and shoot chlorophyll contents (C) of the A. thaliana plants described above were determined with a mean ± sd of four replicates with five pooled plants each. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with the treatment without NA (−NA), *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001 by the Student’s t test.

Effects of Exogenous NA on Zinc and Iron Homeostasis

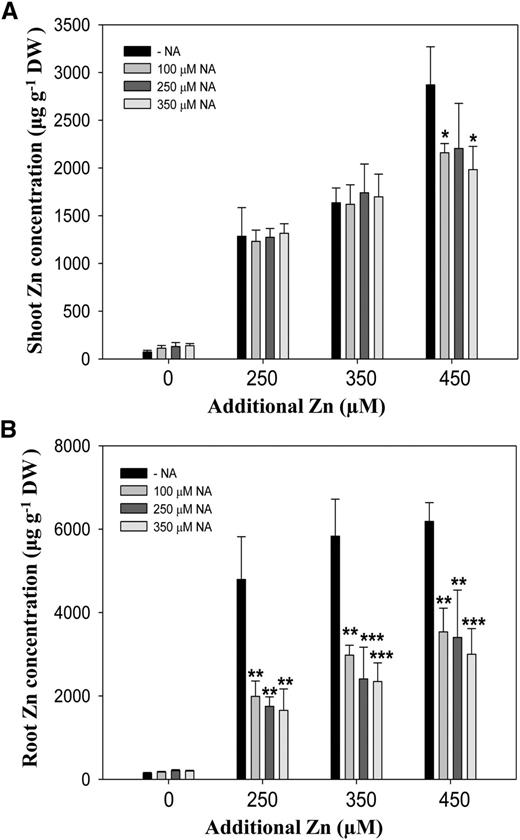

To further confirm whether supplying exogenous NA decreases zinc uptake in zinc-tolerant A. thaliana plants, we quantified the zinc concentrations in roots and shoots (Fig. 7). We found similarly high levels of shoot zinc concentrations in plants supplied both with and without NA (Fig. 7A). The concentration of zinc in roots of NA-supplied plants was decreased significantly (Fig. 7B). This result contrasted with the results of short-term NA supply, in which both root and shoot zinc concentrations were decreased by exogenous NA (Fig. 5). These data therefore suggest that the reduced zinc uptake rate by exogenous NA facilitates plants to accumulate to same shoot zinc concentrations over a prolonged period with increased zinc tolerance.

Zinc accumulation in the presence of NA. A and B, The concentrations of zinc in shoots (A) and roots (B) of A. thaliana grown under additional 250, 350, or 450 μm of excess zinc treatments supplemented with indicated concentrations of exogenous NA as shown in Figure 6A. Four-day-old A. thaliana seedlings grown in one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium were transferred to treatments for 10 d. Data are the mean ± sd of three replicates with eight to 15 pooled plants each. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with treatment without NA (−NA). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001 by the Student’s t test. DW, Dry biomass.

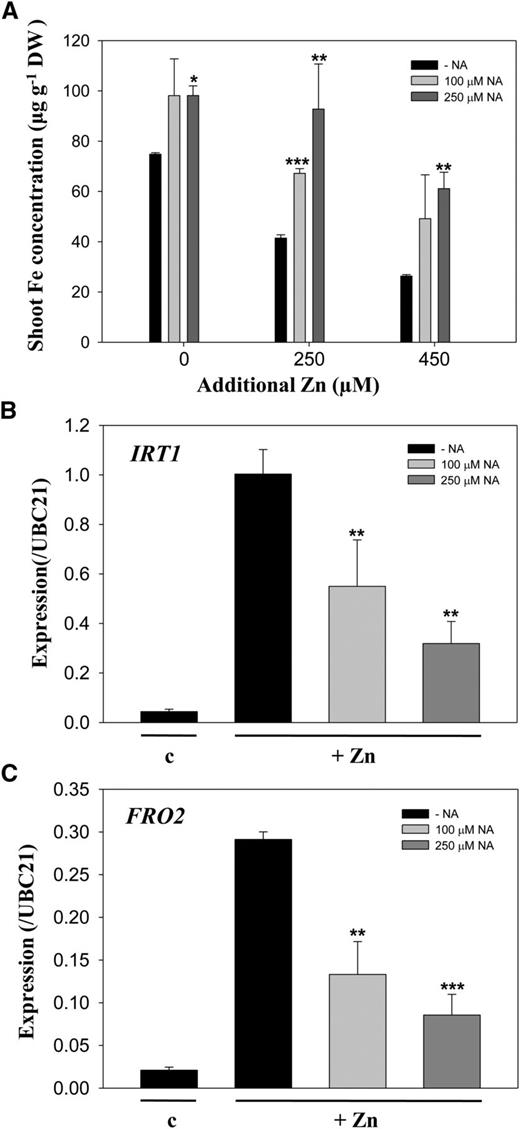

Excess zinc in A. thaliana results in decreased shoot iron content (Shanmugam et al., 2011; Pineau et al., 2012), and the expression of genes related to the iron-acquisition system increases in response to excess zinc (Shanmugam et al., 2011). We therefore checked iron concentrations in shoot tissues of A. thaliana plants. The shoot iron concentrations were significantly higher in NA-supplied plants than in plants without NA supply (Fig. 8A). There were no significant changes in root iron content under excess zinc treatments. We further checked the expression of IRT1 and ferric chelate reductase2 (FRO2) under excess zinc in the presence of NA. We observed that excess zinc-induced expression of IRT1 and FRO2 was significantly suppressed by exogenously applied NA (Fig. 8, B and C). These data suggest that exogenous NA in some way facilitates iron uptake in A. thaliana under excess zinc conditions.

Iron concentration and expression of IRT1 and FRO2 in A. thaliana grown with NA. A, Shoot iron concentrations in A. thaliana plants grown as described in Figure 6. Data are the mean ± sd of three replicates with eight to 15 pooled plants each. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with no NA treatment (−NA). B and C, Transcript levels of IRT1 (B) and FRO2 (C), relative to ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme21 (UBC21), in A. thaliana roots were determined by qRT-PCR. Root samples were collected from 10-d-old A. thaliana seedlings and treated with one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium (c) or 250 μm excess zinc (+Zn) without (−NA) or with 100 or 250 μm NA for 3 d. Data are the mean ± sd of three replicates with five pooled plants each. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with the treatment without NA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001 by the Student’s t test.

DISCUSSION

Metal hyperaccumulation in plants is associated with metal hypertolerance. Metal tolerance in plants is generally achieved in two distinct ways: through blocking the entry of excess amounts of metals into plant roots and/or through detoxification of excess metals that have already entered the plant (Clemens, 2001; Lin and Aarts, 2012). Previous studies have shown enhanced detoxification of zinc ions in zinc-hyperaccumulating A. halleri (Dräger et al., 2004; Shahzad et al., 2010; Hanikenne and Nouet, 2011). However, to our knowledge, the external regulation of potentially available excess concentrations of zinc ions in zinc-polluted soils (Ma and Rao, 1997) by A. halleri has not been studied.

In this study, we used a metabolite-profiling approach to investigate the involvement of root-released metabolites from A. halleri in rhizospheric regulation under excess zinc. A comparison of root-secreted metabolites in root exudates of A. halleri and A. thaliana revealed that A. halleri roots secreted excess zinc-induced NA (Figs. 1 and 2). Furthermore, NA secretion showed consistent induction with excess zinc (Fig. 4). The expression of NAS2 in A. halleri roots was also consistently up-regulated under high concentrations of excess zinc (Supplemental Fig. S7). Based on the data from the hydroponic culture, we further estimated the concentrations of secreted free NA in the rhizosphere volume of A. halleri (Supplemental Fig. S5). The concentrations of root-released metabolites in the rhizosphere are generally considered to be more concentrated than in the liquid culture (Rovira, 1969; Gorban et al., 2000). Our estimations suggest that the concentrations of secreted NA near the A. halleri root surface will be enriched in heavily zinc-polluted environments.

Furthermore, metal speciation analysis revealed that the secreted NA formed a stable complex with Zn(II), as shown in Figure 3. The stability of the Zn(II)-NA complex in the rhizosphere is a point of interest because NA can form complexes with different metals (Rellán-Alvarez et al., 2008). Our metal speciation analysis under hydroponic culture conditions, which was adjusted to an initial pH 5.7 and not further controlled during experiments, showed that the Zn(II)-NA complex is highly stable and abundant under excess zinc (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S6). Because free Zn2+ ions are potentially available in zinc-polluted soils and the stability of the Zn(II)-NA complex is also in the range of pH of these soils, it is possible that the Zn(II)-NA complex is stable and probably quite enriched near the A. halleri root surface.

Supplying exogenous NA further decreased zinc uptake in A. thaliana, indicating that Zn(II)-NA complexes formed outside the roots cannot be taken in or slow down the zinc uptake rate into the root (Fig. 5). Consistent with this, zinc uptake in A. halleri was recently reported to be predominantly in the form of free Zn2+ ions (Aucour et al., 2011). In addition, exogenous application of NA to A. thaliana markedly increased zinc tolerance (Fig. 6). This phenotype may therefore demonstrate a direct function of the exogenous NA without interference from endogenous NA that is present at high levels in A. halleri. As expected, zinc uptake was significantly decreased in zinc-tolerant A. thaliana plants with NA supply (Fig. 7). Together, these observations provide clear evidence that root-secreted NA can regulate zinc bioavailability (i.e. the concentrations of free Zn2+ ions) through forming a nontoxic, probably nonavailable Zn(II)-NA complex in the rhizosphere to confer zinc tolerance.

Similar regulation of the rhizosphere through root-secreted metabolites was reported to confer tolerance to many other toxic heavy metals such as aluminum, cadmium, and lead in several plant species, especially in crops (Yang et al., 2000, 2013; Kochian et al., 2004; Pinto et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2011). Aluminum-tolerance mechanisms in different plant species involve aluminum-induced secretions of different organic acids such as citrate, malate, and oxalate, which then form nontoxic aluminum complexes in the rhizosphere, thereby preventing the binding of aluminum to plasma membrane components and resulting in detoxification (Kochian et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2013).

Comparative physiological studies of two related species can potentially indicate the evolutionary changes that have occurred with regard to specific traits. Because trace NA secretion was also seen in A. thaliana (Figs. 1 and 2), the results obtained with A. thaliana by NA supply may further suggest the role of enhanced NA secretion in the zinc tolerance phenotype in A. halleri. However, instead of reducing zinc accumulation in plants, we think that zinc tolerance in A. halleri by NA secretion might be facilitated through the coordinated zinc uptake rate into roots. Because A. halleri is a zinc-hyperaccumulating plant, its roots continuously absorb zinc from the environment. However, NA secretions to further regulate free Zn2+ ions in the rhizosphere may function as a primary zinc avoidance mechanism to protect A. halleri from zinc toxicity in metal-polluted and heavily zinc-enriched soil environments in which zinc is potentially highly available. Although we cannot rule out the possibility of Zn(II)-NA complex reuptake through YELLOW-STRIPE-LIKE transporters that transport metal-NA complexes (Curie et al., 2009; Conte and Walker, 2012), the uptake rate of zinc is reduced with the formation of the Zn(II)-NA complex. In nonhyperaccumulating plants such as A. thaliana, increased zinc entry into the roots in heavily zinc-enriched environments might easily cause lethal zinc toxicity. In agreement with this hypothesis, previous data also showed that A. halleri does not accumulate more zinc than A. thaliana under the same concentrations of excess zinc media (Shanmugam et al., 2011; Supplemental Fig. S8).

Alternatively, the function of root NA secretions from A. halleri might be for the maintenance of homeostasis of essential micronutrients such as iron in plants under excess zinc conditions. The addition of iron into plants greatly alleviates the toxicity of excess zinc (Shanmugam et al., 2011, 2013), thus conferring tolerance. Supplying A. thaliana with NA provided zinc tolerance (Fig. 6) along with diminished alterations in iron homeostasis (Fig. 8), whereas iron homeostasis was altered under excess zinc treatments in control A. thaliana plants. Because iron content is not affected in zinc-tolerant A. thaliana plants under excess zinc treatments, NA secretion may also play a role in facilitating the availability of iron in the rhizosphere while restricting zinc availability through Zn(II)-NA complex formation. Consistent with this observation, A. halleri was previously reported to maintain stable iron homeostasis under excess zinc in contrast with A. thaliana, which demonstrated loss of shoot iron content and activated iron deficiency response under excess zinc (Shanmugam et al., 2011; Pineau et al., 2012). The stable low level of expression of iron transporter IRT1 and the maintenance of iron homeostasis in A. halleri under excess zinc might therefore result from the decreased competition from free Zn2+ ions by the formation of the Zn(II)-NA complex allowing iron acquisition in the rhizosphere. Therefore, in hyperaccumulating plants, specialized nutrient uptake and/or prevention mechanisms may be regulated not only by specific transporters, but also by high-affinity metal-chelating root-secreted compounds.

In A. halleri roots, NA content is strongly associated with the expression of NAS2 (Weber et al., 2004; Deinlein et al., 2012). Analysis of AhNAS2-RNA interference lines containing root NA content of nearly 20% of the wild type showed loss of zinc hyperaccumulation, but not zinc hypertolerance in transgenic lines (Deinlein et al., 2012). Based on our LC-MS quantification analysis, the amounts of secreted NA in A. halleri root exudates are much lower than in roots under excess zinc treatments. The estimation of secreted NA in the rhizosphere of A. halleri also suggested that the concentrations of NA around the root might be much more concentrated than in the liquid media. It is therefore possible that the decreased root NA content in AhNAS2-RNA interference lines might still be above the threshold level of secretion required for zinc tolerance. Because the elevated expressions of NAS2 and concomitant elevations of NA in roots are consistently observed in different A. halleri individuals (Deinlein et al., 2012), it would be interesting to analyze the NA secretion mechanisms in these individuals.

The overexpression of NAS in A. thaliana previously showed dramatically enhanced nickel tolerance as well as a little zinc tolerance (Kim et al., 2005; Pianelli et al., 2005). The low increases on zinc tolerance may be attributable to the low NA secretion that remained. However, our results with the exogenous NA supply showed significantly increased zinc tolerance in A. thaliana (Fig. 6). We hypothesize that NA inside and outside the plant functions differentially for different metal homeostases. In A. thaliana, the nas quadruple mutant was previously reported to show no phenotype under excess zinc (Klatte et al., 2009; Schuler et al., 2012). Although we observed trace secretion of NA from A. thaliana roots, there was no regulation and/or increase in response to excess zinc treatments. Therefore, in agreement with the findings with the nas mutants, it could also be possible that the small amount of NA secretion from A. thaliana roots might not be sufficient to function in zinc tolerance.

Unlike phytosiderophores, NA is not secreted from grasses (Howe et al., 1999; Tsednee et al., 2012; Supplemental Fig. S1). Efflux transporters of NA (ENA1 and ENA2) were recently reported in rice. However, their biological functions were not studied (Nozoye et al., 2011), nor was NA secretion detected in rice (Takahashi et al., 2003; Kobayashi et al., 2010). The phytosiderophore exporter TRANSPORTER OF MUGINEIC ACID1 showed no NA transport activity (Nozoye et al., 2011). The TRANSPORTER OF MUGINEIC ACID1 homolog in A. thaliana (ZINC-INDUCED FACILITATOR1) is localized in the tonoplast (Haydon and Cobbett, 2007) and it is unlikely that it functions in the secretion of NA. However, it may function in subsequent sequestration of excess zinc into vacuoles like the Nramp aluminum transporter1 for aluminum detoxification in rice (Xia et al., 2010). Related transporters such as other ZINC-INDUCED FACILITATOR-like transporters could also be candidates for further examination of NA secretion. In A. halleri, NA concentrations inside the roots increased about 2-fold under excess zinc; however, NA secretion showed consistent increases of about 3-fold under excess zinc (Figs. 2 and 4). These findings suggest that the expression and regulation of the NA efflux transporters are critical in A. halleri under excess zinc conditions. Identifying the NA secretion mechanism should therefore extend understanding of zinc tolerance in A. halleri.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

NA (95%) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. Acetonitrile (analytical grade; Fluka), and Leu enkephalin, and nicotine (LC grade) were from Sigma. 67Zn (97%, ZnSO4) was from Trace Sciences International. Formic acid (FA) and methanol (LC grade) were from Mallinckrodt Baker.

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Ecotype Columbia-0 of Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown from sterile seeds after germination on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium containing one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog salt, 0.3% (w/v) phytagel, 500 mg L−1 MES, and 1% (w/v) Suc, pH 5.7. Arabidopsis halleri ssp. gemmifera (N35.86896, E136.254979; heavily metal-contaminated soil site in Fumuro, Japan) was propagated from sterile cuttings that were maintained in a stable sterile tissue culture system with the same Murashige and Skoog medium in a magenta box (Sigma-Aldrich; Chiang et al., 2006). Plant growth conditions were as follows: light intensity, 70 μmol m−2s−1; 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle; and temperature, 22°C.

For metabolic profiling and metal speciation analysis, 10-d-old A. thaliana and 3-week root-induced A. halleri plants grown in one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium were transferred to hydroponic culture solutions containing modified one-half-strength Hoagland nutrient solution [3 mm KNO3, 2 mm Ca(NO3)2, 0.5 mm NH4H2PO4, 1 mm MgSO4, 46.2 μm H3BO3, 9.1 mm MnCl2, 0.8 μm ZnSO4, 0.3 μm CuSO4, 0.08 μm Na2MoO4, and 5 μm NaFeEDTA]. In an open hydroponic system, each culture container of 500-mL culture solution contained four and eight individual A. halleri and A. thaliana plants, respectively. Treatments were started after a 7-d hydroponic adaptation. For iron deficiency treatment, 5 μm ferrozine was added to the nutrient solution instead of NaFeEDTA. For excess zinc treatment, 10 μm and 100 μm additional ZnSO4 were added into A. thaliana and A. halleri culture solutions, respectively. The nutrient solution was renewed every 3 d.

For 67Zn stable isotope measurement, 15-d-old hydroponically grown A. thaliana plants were transferred to treatment solutions containing an additional 0.5, 10, 50, and 100 μm 67ZnSO4 supplied with (50 μm NA) and without exogenous NA standard for 24 h. For measurement of normal metal concentrations in A. thaliana plants, 4-d-old A. thaliana seedlings grown in one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium were transferred to one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with additional ZnSO4 with NA for 10 d.

For metabolite analysis of barley (Hordeum vulgare), plants were germinated and then grown hydroponically, and samples were collected as described (Tsednee et al., 2012).

Collection of Root Exudates and Metabolite-Profiling Analysis

For metabolite-profiling analysis of root exudates, the root exudates of hydroponically grown A. thaliana and A. halleri plants were collected in distilled deionized water every 2 d on five occasions starting at the 3rd d of treatments and prepared for analysis as previously described (Tsednee et al., 2012). Briefly, before exudate collection, the plants were removed from nutrient solution, and the roots were washed a few times with distilled water. The plant root systems were then submerged in 500 mL of distilled deionized water for 4 h for exudate collection. After collection, plants were placed back into fresh culture solution. For time-course studies, exudates were collected for 4 h at the time points indicated. Care was taken in handling to avoid artificial secretions of metabolites from damaged roots. The sterilities of nutrient solutions and collected root exudates were also validated with microbial contaminations as previously described (von Wiren et al., 1994; Tsednee et al., 2012). After addition of an internal standard (nicotine, 100 ppm) into concentrated root exudates, the samples were subjected to UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS (ACQUITY Ultra Performance LC) coupled with hybrid Q-TOF-MS (Synapt HDMS; Waters).

The samples were further separated on an UPLC BEH HILIC column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm; Waters) by gradient elution at a column temperature of 40°C in positive ESI mode. In UPLC, mobile phases consisted of 0.1% (v/v) FA in 2% (v/v) acetonitrile (ACN) as buffer A, and 0.1% (w/v) FA in 100% ACN as buffer B. The gradient conditions used were as follows: buffer A, 99.5% to 5.0% in 0 to 8.0 min, 5.0% to 5.0% in 8.0 to 9.0 min, 5.0% to 99.5% in 9.0 to 10.0 min, and 99.5% to 99.5% in 10.0 to 14.0 min. The mobile-phase flow rate was 0.3 mL min−1. The HDMS device was operated as previously described (Tsednee et al., 2012). MS data were processed using MarkerLynx XS 4.1 SCN639 within MassLynx 4.1 software (Waters) by filtering MS peaks with intensity < 30 counts. EZinfo 2.0 software with Pareto scaling was applied for principal component analysis and OPLS-DA. Data sets were further analyzed with OPLS-DA to generate S plots for biomarker identification.

NA and NA-Metal Speciation Analysis

To quantify NA in roots, 100 mg of fresh roots was homogenized and extracted with 1 mL of 80% (v/v) methanol for 30 min under sonication at 25°C. The concentrated root exudates described above were used directly for the analysis. After adding an internal standard (Leu encephalin, 0.2 ppm) into samples, the microfiltered root extracts and root exudates were further separated on an UPLC BEH HILIC column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm; Waters) at 40°C with elution gradients of a mobile phase that consisted of 0.1% FA in 2% (v/v) ACN (buffer A) and 0.1% (v/v) FA in 100% ACN (buffer B). Gradient conditions used were as follows: buffer A, 99.5% to 5.0%, 0 to 8.0 min; 5.0% to 5.0%, 8.0 to 9.0 min; 5.0% to 99.5%, 9.0 to 9.5 min; and 99.5% to 99.5%, 9.5 to 10.5 min. The flow rate was 0.3 mL min−1. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ESI mode. The concentrations of NA were calculated using the normalized peak areas against the standard linear equation built from 10 different concentrations of NA standard in extraction buffer and water for roots and root exudate samples, respectively, with r 2 values being higher than 0.98. Matrix signal suppressions on the NA peak in analyzed samples were validated by identifying NA in the series of diluted samples for each treatment from both plants. Further analysis of NA in the samples was conducted with the MS/MS spectrum for each injection to confirm the peak.

For identification of the NA-metal complexes, samples were separated on an UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 150 mm; Waters) at 40°C with a flow rate of 0.3 mL min−1. The mobile phase consisted of 2% (v/v) ACN (buffer A) and 100% ACN (buffer B). Elution gradients were as follows: buffer A, 99.5% to 5.0%, 0 to 4.0 min; 5.0% to 5.0%, 4.0 to 4.5 min; 5.0% to 99.5%, 4.5 to 4.8 min; and 99.5% to 99.5%, 4.8 to 6.3 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in negative ESI mode. NA-metal complex identifications were confirmed using NA-metal standard complexes prepared as previously described (Tsednee et al., 2012). Relative abundances of metal complexes were obtained by comparing the normalized peak areas of the complexes to the internal control (Leu enkephalin, 0.2 ppm).

Elemental Analysis

For measurement of 67Zn stable isotope and normal zinc in roots and shoots, the plant tissues were harvested, washed with 10 mm CaCl2 before drying, and digested with 0.5 n nitric acid. Concentrations of elements were determined with sector-field double-focusing HR-ICP-MS (Element XR; Thermo Scientific) as previously described (Ho et al., 2003).

Chlorophyll Measurements

To measure chlorophyll concentrations, the total chlorophyll from leaf tissue was extracted with 95% (v/v) ethanol at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The chlorophyll content in the supernatant was quantified spectrophotometrically using A 665 and 649 nm as previously described (Wintermans and de Mots, 1965).

Transcript Analysis

For real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), 10-d-old A. thaliana seedlings grown in one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium were transferred to control and excess zinc phytagel Murashige and Skoog medium without and with supplied NA for 3 d. RNA extraction and reverse transcription were performed as described previously (Chen et al., 2011). qRT-PCR involved using the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems) with the StepOnePlus RT-PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences are given in Supplemental Table S4.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers At4g19690 (IRT1), At1g01580 (FRO2), and At5g25760 (UBC21).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Identification of NA in barley roots and exudates.

Supplemental Figure S2. Identification of glutathione and scopoletin in roots and root exudates (exud) of A. halleri and A. thaliana roots under control and excess zinc treatment conditions.

Supplemental Figure S3. Chromatograms of the detected metal-NA complexes in A. halleri samples.

Supplemental Figure S4. Stability of Zn(II)-NA complexes in the root exudates of A. halleri.

Supplemental Figure S5. Estimated concentrations of secreted NA in the rhizosphere of A. halleri.

Supplemental Figure S6. Stoichiometry of NA and Zn(II)-NA complex formation.

Supplemental Figure S7. Expression of NAS genes in A. halleri leaves and roots under different concentrations of excess zinc treatments.

Supplemental Figure S8. Zinc uptake in A. halleri and A. thaliana.

Supplemental Table S1. Higher abundances of metabolites are secreted from A. halleri than A. thaliana under control conditions.

Supplemental Table S2. Metabolites secreted from roots of A. halleri under excess zinc.

Supplemental Table S3. Calculated and observed m/z values of NA.

Supplemental Table S4. Sequence of primers used for qRT-PCR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Academia Sinica Metabolomics Core Facility for performing the MS analysis; Yet-Ran Chen, Chih-Yu Lin, and Jing-Chi Lo for helpful discussions and providing supporting information; and Miranda Loney for manuscript editing.

Glossary

- NA

nicotianamine

- UPLC

ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- Q-TOF

quadruple time-of-flight

- MS

mass spectrometry

- HILIC

hydrophilic column

- OPLS-DA

orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis

- m/z

mass-to-charge ratio

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- HR-ICP

high-resolution-inductively coupled plasma

- FA

formic acid

- ACN

acetonitrile

- qRT

quantitative reverse transcription

LITERATURE CITED

Author notes

This work was supported by Academia Sinica and the National Science Council of Taiwan (grant no. NSC 102–2321–B–001–043).

Address correspondence to [email protected].

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Kuo-Chen Yeh ([email protected]).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.