-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Matthew Fisher, Lauren Komarow, Jordan Kahn, Gopi Patel, Sara Revolinski, W Charles Huskins, David van Duin, Ritu Banerjee, Bettina C Fries, for the MDRO Network Investigators, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in Children at 18 US Health Care System Study Sites: Clinical and Molecular Epidemiology From a Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 11, Issue 2, February 2024, ofad688, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad688

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) are an urgent public health threat in the United States.

Describe the clinical and molecular epidemiology of CRE in a multicenter pediatric cohort.

CRACKLE-1 and CRACKLE-2 are prospective cohort studies with consecutive enrollment of hospitalized patients with CRE infection or colonization between 24 December 2011 and 31 August 2017. Patients younger than age 18 years and enrolled in the CRACKLE studies were included in this analysis. Clinical data were obtained from the electronic health record. Carbapenemase genes were detected using polymerase chain reaction and whole-genome sequencing.

Fifty-one children were identified at 18 healthcare system study sites representing all U.S. census regions. The median age was 8 months, with 67% younger than age 2 years. Median number of days from admission to culture collection was 11. Seventy-three percent of patients had required intensive care and 41% had a history of mechanical ventilation. More than half of children had no documented comorbidities (Q1, Q3 0, 2). Sixty-seven percent previously received antibiotics during their hospitalization. The most common species isolated were Enterobacter species (41%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (27%), and Escherichia coli (20%). Carbapenemase genes were detected in 29% of isolates tested, which was lower than previously described in adults from this cohort (61%). Thirty-four patients were empirically treated on the date of culture collection, but only 6 received an antibiotic to which the CRE isolate was confirmed susceptible in vitro. Thirty-day mortality was 13.7%.

CRE infection or colonization in U.S. children was geographically widespread, predominantly affected children younger than age 2 years, associated with significant mortality, and less commonly caused by carbapenemase-producing strains than in adults.

Antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections pose a significant threat to public health. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) as one of the most urgent of these threats in the United States, associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1, 2].

The CDC define CRE by the in vitro resistance to 1 or more carbapenem antibiotics, which may or may not be conferred by the presence of a carbapenemase enzyme [2]. These carbapenemase-producing organisms are of particular concern because the spread of CRE has been largely attributed to transferable plasmid-encoded carbapenemase genes, the most common of which in the United States are the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC) [3–6]. Risk factors for acquisition of CRE in adults include previous exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, residence in a long-term care facility, prior surgery, and immunocompromised status [3, 4, 7]. Foreign travel or hospitalization have also been identified as specific risk factors for acquiring carbapenemase-producing CRE in adults [8].

The prevalence of CRE in children has been increasing over the past 2 decades, but less is known about the clinical and molecular characteristics of CRE in children than in adults [9–11]. Much of what is known about pediatric CRE in the United States has come from local outbreaks, case series, and retrospective case-control studies [12–15]. Additional comprehensive studies are needed to elucidate the epidemiologic burden of pediatric CRE in the United States. Two prospective, observational multicenter cohort studies, CRACKLE-1 and CRACKLE-2 (Consortium on Resistance Against Carbapenems in Klebsiella and other Enterobacteriaceae), which collectively enrolled patients between December 2011 and August 2017, together comprise a large, geographically diverse, and comprehensive database of CRE in both children and adults throughout the United States [16, 17]. In this study we describe the clinical, microbiologic, and molecular epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes of CRE infection in the 51 pediatric patients from these cohorts.

METHODS

Study Participants and Design

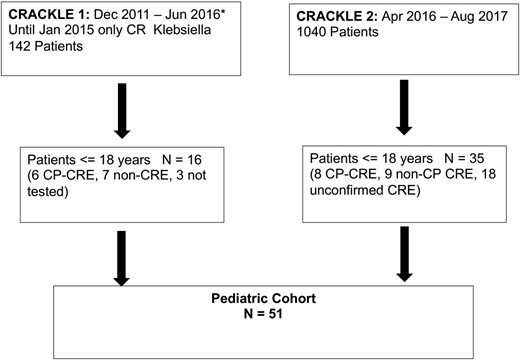

CRACKLE-1 and -2 were prospective, observational, multicenter studies with consecutive enrollment of hospitalized patients from 49 healthcare system sites comprising 70 participating hospitals in 15 U.S. states and the District of Columbia between 24 December 2011 and 29 June 2016 (CRACKLE-1) and from 30 April 2016 to 31 August 2017 (CRACKLE-2) [16, 17]. From 24 December 2011, until 1 January 2015, only data on patients with carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae were collected. From 1 January 2015 onward, all consecutive patients with any CRE were included. Children aged 18 years and younger with CDC-defined CRE isolated in a clinical culture from any anatomic site were included in this analysis.

Microbiologic and Molecular Analysis

Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed at each local contributing clinical microbiology laboratory using MicroScan (Beckman Coulter, Atlanta, Georgia), Vitek 2, Etest (bioMérieux, Durham, North Carolina), BD Phoenix, BBL disks (Becton Dickinson, Durham, North Carolina), Sensititre (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts), disk diffusion, or in-house agar dilution. Carbapenem susceptibility was subsequently confirmed at 2 independent central research laboratories using Etest and Microscan (Beckman Coulter). For patients recruited in CRACKLE-1, CRE were defined according to 2012 CDC guidelines, which required resistance to all third-generation cephalosporins. For the CRACKLE-2 patients, CRE were defined according to current CDC guidelines that were updated in 2015 to eliminate this requirement [2, 16]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers for blaKPC, blaNDM blaVIM, blaIMP, and blaOXA-48 was performed for detection of carbapenemase genes in isolates from CRACKLE-1 and whole-genome sequencing was performed in CRACKLE-2 patients and therefore included a larger list of carbapenemase genes. All CRE isolates collected during CRACKLE-2 were further subclassified as CP-CRE isolates if they harbored a carbapenemase gene and as non–CP-CRE if they exhibited in vitro carbapenem resistance but a carbapenemase gene was not detected by PCR. In CRACKLE-2 those isolates that were identified as non-carbapenemase producing CRE were further tested by broth microdilution in a central research laboratory. Those isolates for which repeat susceptibility testing at the central laboratories demonstrated susceptibility to carbapenems were classified as unconfirmed CRE, as described in previous publications [16].

Clinical and Demographic Data

Clinical and demographic data including patient age, gender, race, hospital geographic location, preadmission origin, comorbid conditions (heart disease including congestive heart failure and coronary artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular disease, malignancy, stem cell transplant, solid organ transplant, diabetes, HIV infection, immunocompromised), Pitt bacteremia score [18], need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, source of culture, and antibiotic therapy were extracted from the electronic medical record. Whether a patient was considered infected or colonized was determined based on standardized criteria, which are outlined in prior publications [16, 17]. Comorbidities were assessed for the entire CRACKLE cohorts and were not specific to pediatrics. Antibiotic therapy was divided into those antibiotics received before the date of the index culture (for the CRACKLE-1 cohort it was limited to within 14 days before the index culture), and those received on the date of the culture up to 30 days afterward. The primary outcomes assessed were 30-day and 90-day all-cause mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are summarized using median with first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3), and categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Exact (Clopper-Pearson) 2-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for mortality. In this observational study, censoring was absent because, unless known to have died, patients were assumed to be alive at 30 days after initial culture. Data were summarized using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Patient Demographic Characteristics

Fifty-one pediatric patients from 18 healthcare systems (see Supplementary data) each contributed a CRE culture (Table 1), including 16 patients from CRACKLE-1 and 35 from CRACKLE-2 (Figure 1). Patients were from all census regions of the United States, most commonly from the South (46%), followed by the Northeast (24%), Midwest (20%), and West (10%). A significant portion of the pediatric patients represented racial and ethnic minorities, including 39% who identified as Black and 19% as Hispanic. This is compared with 37% Black and 2% Hispanic (CRACKLE-1) and 32% Black and 12% Hispanic (CRACKLE-2) patients in the entire cohorts comprised mostly of adults.

| . | No. (%), Unless Otherwise Specified . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 27 (53%) |

| Female | 24 (47%) | |

| Age at positive culture, mo Median (Q1, Q3) | 8 (2.6, 85) | |

| Age subgroups | 0–3 mo | 14 (27%) |

| 3 mo–2 y | 20 (39%) | |

| >2 y | 17 (33%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 20 (39%) |

| Black | 20 (39%) | |

| Asian | 1 (2%) | |

| Other | 2 (4%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (16%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (18%) | |

| Region | Northeast | 12 (24%) |

| South | 23 (46%) | |

| Midwest | 10 (20%) | |

| West | 5 (10%) | |

| Preadmission origin | Community | 28 (55%) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 9 (18%) | |

| Long-term care facility | 2 (4%) | |

| Admitted at birth | 11 (22%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) | |

| Comorbidities | Heart disease | 6 (12%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5 (10%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (8%) | |

| Liver disease (cirrhosis, portal hypertension) | 3 (6%) | |

| History of malignancy | 7 (14%) | |

| Solid organ transplant | 4 (8%) | |

| Stem cell transplant | 3 (7%) | |

| Diabetes | 4 (8%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (2%) | |

| Immunocompromised | 10 (20%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 37 (73%) | |

| Mechanical ventilation prior to culture | 21 (41%) | |

| Days from admission to culture, median (Q1, Q3) | 11 (1, 26) | |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (Q1, Q3) | 3 (1, 6) | |

| Infection | 28 (55%) | |

| Percent of patients receiving antibiotic before date of CRE culture collection | Ampicillin | 9 (18%) |

| Gentamicin | 8 (16%) | |

| Meropenem | 9 (18%) | |

| Cefepime | 8 (16%) | |

| Ceftriaxone | 12 (24%) | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2 (4%) | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 12 (24%) | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 5 (10%) | |

| Other | 10 (20%) | |

| . | No. (%), Unless Otherwise Specified . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 27 (53%) |

| Female | 24 (47%) | |

| Age at positive culture, mo Median (Q1, Q3) | 8 (2.6, 85) | |

| Age subgroups | 0–3 mo | 14 (27%) |

| 3 mo–2 y | 20 (39%) | |

| >2 y | 17 (33%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 20 (39%) |

| Black | 20 (39%) | |

| Asian | 1 (2%) | |

| Other | 2 (4%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (16%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (18%) | |

| Region | Northeast | 12 (24%) |

| South | 23 (46%) | |

| Midwest | 10 (20%) | |

| West | 5 (10%) | |

| Preadmission origin | Community | 28 (55%) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 9 (18%) | |

| Long-term care facility | 2 (4%) | |

| Admitted at birth | 11 (22%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) | |

| Comorbidities | Heart disease | 6 (12%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5 (10%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (8%) | |

| Liver disease (cirrhosis, portal hypertension) | 3 (6%) | |

| History of malignancy | 7 (14%) | |

| Solid organ transplant | 4 (8%) | |

| Stem cell transplant | 3 (7%) | |

| Diabetes | 4 (8%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (2%) | |

| Immunocompromised | 10 (20%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 37 (73%) | |

| Mechanical ventilation prior to culture | 21 (41%) | |

| Days from admission to culture, median (Q1, Q3) | 11 (1, 26) | |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (Q1, Q3) | 3 (1, 6) | |

| Infection | 28 (55%) | |

| Percent of patients receiving antibiotic before date of CRE culture collection | Ampicillin | 9 (18%) |

| Gentamicin | 8 (16%) | |

| Meropenem | 9 (18%) | |

| Cefepime | 8 (16%) | |

| Ceftriaxone | 12 (24%) | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2 (4%) | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 12 (24%) | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 5 (10%) | |

| Other | 10 (20%) | |

Abbreviations: CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; Q, quartile.

| . | No. (%), Unless Otherwise Specified . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 27 (53%) |

| Female | 24 (47%) | |

| Age at positive culture, mo Median (Q1, Q3) | 8 (2.6, 85) | |

| Age subgroups | 0–3 mo | 14 (27%) |

| 3 mo–2 y | 20 (39%) | |

| >2 y | 17 (33%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 20 (39%) |

| Black | 20 (39%) | |

| Asian | 1 (2%) | |

| Other | 2 (4%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (16%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (18%) | |

| Region | Northeast | 12 (24%) |

| South | 23 (46%) | |

| Midwest | 10 (20%) | |

| West | 5 (10%) | |

| Preadmission origin | Community | 28 (55%) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 9 (18%) | |

| Long-term care facility | 2 (4%) | |

| Admitted at birth | 11 (22%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) | |

| Comorbidities | Heart disease | 6 (12%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5 (10%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (8%) | |

| Liver disease (cirrhosis, portal hypertension) | 3 (6%) | |

| History of malignancy | 7 (14%) | |

| Solid organ transplant | 4 (8%) | |

| Stem cell transplant | 3 (7%) | |

| Diabetes | 4 (8%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (2%) | |

| Immunocompromised | 10 (20%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 37 (73%) | |

| Mechanical ventilation prior to culture | 21 (41%) | |

| Days from admission to culture, median (Q1, Q3) | 11 (1, 26) | |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (Q1, Q3) | 3 (1, 6) | |

| Infection | 28 (55%) | |

| Percent of patients receiving antibiotic before date of CRE culture collection | Ampicillin | 9 (18%) |

| Gentamicin | 8 (16%) | |

| Meropenem | 9 (18%) | |

| Cefepime | 8 (16%) | |

| Ceftriaxone | 12 (24%) | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2 (4%) | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 12 (24%) | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 5 (10%) | |

| Other | 10 (20%) | |

| . | No. (%), Unless Otherwise Specified . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 27 (53%) |

| Female | 24 (47%) | |

| Age at positive culture, mo Median (Q1, Q3) | 8 (2.6, 85) | |

| Age subgroups | 0–3 mo | 14 (27%) |

| 3 mo–2 y | 20 (39%) | |

| >2 y | 17 (33%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 20 (39%) |

| Black | 20 (39%) | |

| Asian | 1 (2%) | |

| Other | 2 (4%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (16%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (18%) | |

| Region | Northeast | 12 (24%) |

| South | 23 (46%) | |

| Midwest | 10 (20%) | |

| West | 5 (10%) | |

| Preadmission origin | Community | 28 (55%) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 9 (18%) | |

| Long-term care facility | 2 (4%) | |

| Admitted at birth | 11 (22%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) | |

| Comorbidities | Heart disease | 6 (12%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5 (10%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (8%) | |

| Liver disease (cirrhosis, portal hypertension) | 3 (6%) | |

| History of malignancy | 7 (14%) | |

| Solid organ transplant | 4 (8%) | |

| Stem cell transplant | 3 (7%) | |

| Diabetes | 4 (8%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (2%) | |

| Immunocompromised | 10 (20%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 37 (73%) | |

| Mechanical ventilation prior to culture | 21 (41%) | |

| Days from admission to culture, median (Q1, Q3) | 11 (1, 26) | |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (Q1, Q3) | 3 (1, 6) | |

| Infection | 28 (55%) | |

| Percent of patients receiving antibiotic before date of CRE culture collection | Ampicillin | 9 (18%) |

| Gentamicin | 8 (16%) | |

| Meropenem | 9 (18%) | |

| Cefepime | 8 (16%) | |

| Ceftriaxone | 12 (24%) | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2 (4%) | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 12 (24%) | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 5 (10%) | |

| Other | 10 (20%) | |

Abbreviations: CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; Q, quartile.

The median patient age at the time of positive culture was 8 months (Q1, 2.6 months; Q3, 85 months), with 67% of children younger than age 2 years, including 11 neonates who were admitted to the hospital at birth. The length of hospital stay for 9 of these infants ranged from 36 to 226 days. Fifty-five percent of the patients (n = 28) were admitted from home, with the remainder transferred from other hospitals or long-term care facilities.

Clinical Factors and Comorbidities

More than half of children hospitalized with CRE in the cohort had no documented comorbidities (Q1, 0 comorbidities; Q3, 2 comorbidities). The most cited comorbidity was malignancy, which was present in 7 children (14%). A notable subset of 10 patients (20%) was considered immunocompromised, including 3 children who had received recent or current chemotherapy and 3 patients who had undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Chronic kidney disease was reported in 4 (8%) children and liver disease in 4 (6%) children.

The median Pitt bacteremia score was 3 (Q1, 1; Q3, 6) at the time of the first positive culture. Seventy-three percent of children had been admitted to an ICU during their hospitalization, including 11 (22%) in the neonatal ICU. Before culture collection, 21 (41%) patients required mechanical ventilation.

A total of 34 patients (67%) received antibiotics before the date of the index culture. The most common antibiotics received were third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins (35%), piperacillin-tazobactam (24%), and meropenem (18%). Ten children received 3 or more different classes of antibiotics during their hospitalization before culture collection.

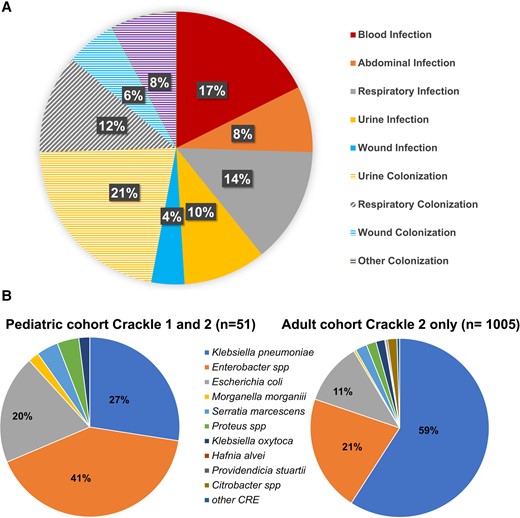

A total of 28 CRE (55%) cultures met criteria for true infection. The median (Q1, Q3) time from admission to positive culture was 11 (1, 26) days. The most common source of a positive culture was urine from 16 patients (31%), followed by respiratory specimens from 13 (25%), and blood from 9 (18%) (Figure 2A).

A, Sites from which carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) isolates were recovered in pediatric patients. Isolates meeting criteria for infection are shown in solid colors, and those isolates that did not meet criteria for infection are shown in shaded colors. B, Species distribution in pediatric CRACKLE-1 and CRACKLE-2 (n = 51) and adult CRACKLE-2 cohorts (n = 1005).

Microbiologic and Molecular Characteristics

The most common species isolated were Enterobacter species from 21 patients (41%), K. pneumoniae from 14 (27%), E. coli from 10 (20%), 2 Serratia marcescens, 1 Proteus mirabilis, 1 Morganella morganii, 1 Klebsiella oxytoca, and 1 for which the species was unknown (Figure 2B). Six K. pneumoniae isolates were derived from the CRACKLE-1 study, which, in the beginning, only collected K. pneumoniae. The species distribution in pediatric differed from that found in adult patients from the CRACKLE-2 cohorts, in which K. pneumoniae isolates constituted 59% of the isolates and Enterobacter spp 21%, respectively (Figure 2B).

Importantly, carbapenemase genes were only detected in 14 of 48 (29%) isolates tested, which is a lower percentage when compared with the adult cohort of CRACKLE-2, which recorded carbapenemase genes in 618 of 1005 (61%). CP-CRE isolates included 6 harboring blaKPC-2, 3 with blaKPC-3, and 1 each with blaKPC-4, blaNDM-1, blaNDM-5, blaNMC-A, and blaOXA-232. In CRACKLE-2, 8 isolates were CP-CRE, 9 isolates were classified as non–CP-CRE, and in 18 of 35 isolates the central laboratory did not confirm resistance to ertapenem; however, all those isolates were reported by local submitting laboratories under CDC guidelines as CRE. The 18 unconfirmed CRE isolates derived from CRACKLE-2 included 6 Enterobacter species, 6 E. coli, 3 K. pneumoniae, 1 K. oxytoca, and 2 S. marcescens. Of these, only 6 were deemed to be true infection.

Antibiotic Resistance and Empiric Therapy

Antibiotic resistance was observed across multiple classes of antibiotics but not consistently tested in all isolates. Overall susceptibility was lowest for ertapenem (0%, 0/47 tested), aztreonam (13%, 3/23 tested), piperacillin-tazobactam (28%, 13/46 tested), and cefepime (39%, 16/41 tested). Susceptibility was higher for ciprofloxacin (61%, 20/33 tested), gentamicin (66%, 33/50 tested), amikacin (63%, 17/27 tested), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (59%, 24/41 tested).

In Table 2, antibiotic susceptibilities are shown for CP-CRE from CRACKLE-1 and CRACKLE-2, non–CP-CRE from CRACKLE-2, and unconfirmed CRE from CRACKLE-2. (Non–carbapenemase-producing isolates from CRACKLE-1 that did not undergo confirmatory susceptibility testing are excluded.)

| Antibiotic . | Susceptibility . | CP-CRE (n = 14) . | Non-CP CRE (n = 9) . | Unconfirmed CRE (n = 18) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | Resistant | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) |

| Intermediate | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Susceptible | 5 (50%) | 4 (100%) | 8 (73%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| Aztreonam | Resistant | 8 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (67%) |

| Susceptible | 0 | 0 | 3 (33%) | |

| Not tested | 6 | 3 | 9 | |

| Cefepime | Resistant | 11 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (24%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (19%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 4 (50%) | 9 (56%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | Resistant | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 | |

| Not tested | 11 | 17 | 18 | |

| Ceftriaxone | Resistant | 13 (93%) | 5 (100%) | 14 (93%) |

| Susceptible | 1 (7%) | 0 | 1 (7%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Resistant | 7 (64%) | 1 (14%) | 4 (31%) |

| Susceptible | 4 (36%) | 6 (86%) | 9 (69%) | |

| Not tested | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Colistin | Resistant | 0 | 0 | 1(50%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (33%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 2 (67%) | 1(100%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 11 | 8 | 16 | |

| Ertapenem | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 17 (100%) |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gentamicin | Resistant | 11 (46%) | 0 | 13 (26%) |

| Intermediate | 0 | 0 | 4 (8%) | |

| Susceptible | 3 (54%) | 8 (100%) | 33 (66%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Imipenem | Resistant | 7 (78%) | 0 | 3 (30%) |

| Intermediate | 2 (22%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 7 (70%) | |

| Not tested | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| Meropenem | Resistant | 12 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 9 (53%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2(25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 | 4 (50%) | 8 (47%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Polymyxin/b | Resistant | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 3 (75%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not tested | 10 | 9 | 18 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 5 (62%) | 6 (33%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (17%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 0 | 9 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Tobramycin | Resistant | 8 (67%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (14%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 0 | 3 (21%) | |

| Susceptible | 4 (33%) | 4 (80%) | 9 (64%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 4 | 10 | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Resistant | 8 (62%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (24%) |

| Susceptible | 5 (38%) | 4 (50%) | 13 (76%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Antibiotic . | Susceptibility . | CP-CRE (n = 14) . | Non-CP CRE (n = 9) . | Unconfirmed CRE (n = 18) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | Resistant | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) |

| Intermediate | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Susceptible | 5 (50%) | 4 (100%) | 8 (73%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| Aztreonam | Resistant | 8 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (67%) |

| Susceptible | 0 | 0 | 3 (33%) | |

| Not tested | 6 | 3 | 9 | |

| Cefepime | Resistant | 11 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (24%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (19%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 4 (50%) | 9 (56%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | Resistant | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 | |

| Not tested | 11 | 17 | 18 | |

| Ceftriaxone | Resistant | 13 (93%) | 5 (100%) | 14 (93%) |

| Susceptible | 1 (7%) | 0 | 1 (7%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Resistant | 7 (64%) | 1 (14%) | 4 (31%) |

| Susceptible | 4 (36%) | 6 (86%) | 9 (69%) | |

| Not tested | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Colistin | Resistant | 0 | 0 | 1(50%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (33%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 2 (67%) | 1(100%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 11 | 8 | 16 | |

| Ertapenem | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 17 (100%) |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gentamicin | Resistant | 11 (46%) | 0 | 13 (26%) |

| Intermediate | 0 | 0 | 4 (8%) | |

| Susceptible | 3 (54%) | 8 (100%) | 33 (66%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Imipenem | Resistant | 7 (78%) | 0 | 3 (30%) |

| Intermediate | 2 (22%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 7 (70%) | |

| Not tested | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| Meropenem | Resistant | 12 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 9 (53%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2(25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 | 4 (50%) | 8 (47%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Polymyxin/b | Resistant | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 3 (75%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not tested | 10 | 9 | 18 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 5 (62%) | 6 (33%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (17%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 0 | 9 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Tobramycin | Resistant | 8 (67%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (14%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 0 | 3 (21%) | |

| Susceptible | 4 (33%) | 4 (80%) | 9 (64%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 4 | 10 | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Resistant | 8 (62%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (24%) |

| Susceptible | 5 (38%) | 4 (50%) | 13 (76%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviation: CP-CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates with a carbapenemase gene.

| Antibiotic . | Susceptibility . | CP-CRE (n = 14) . | Non-CP CRE (n = 9) . | Unconfirmed CRE (n = 18) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | Resistant | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) |

| Intermediate | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Susceptible | 5 (50%) | 4 (100%) | 8 (73%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| Aztreonam | Resistant | 8 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (67%) |

| Susceptible | 0 | 0 | 3 (33%) | |

| Not tested | 6 | 3 | 9 | |

| Cefepime | Resistant | 11 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (24%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (19%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 4 (50%) | 9 (56%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | Resistant | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 | |

| Not tested | 11 | 17 | 18 | |

| Ceftriaxone | Resistant | 13 (93%) | 5 (100%) | 14 (93%) |

| Susceptible | 1 (7%) | 0 | 1 (7%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Resistant | 7 (64%) | 1 (14%) | 4 (31%) |

| Susceptible | 4 (36%) | 6 (86%) | 9 (69%) | |

| Not tested | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Colistin | Resistant | 0 | 0 | 1(50%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (33%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 2 (67%) | 1(100%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 11 | 8 | 16 | |

| Ertapenem | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 17 (100%) |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gentamicin | Resistant | 11 (46%) | 0 | 13 (26%) |

| Intermediate | 0 | 0 | 4 (8%) | |

| Susceptible | 3 (54%) | 8 (100%) | 33 (66%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Imipenem | Resistant | 7 (78%) | 0 | 3 (30%) |

| Intermediate | 2 (22%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 7 (70%) | |

| Not tested | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| Meropenem | Resistant | 12 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 9 (53%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2(25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 | 4 (50%) | 8 (47%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Polymyxin/b | Resistant | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 3 (75%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not tested | 10 | 9 | 18 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 5 (62%) | 6 (33%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (17%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 0 | 9 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Tobramycin | Resistant | 8 (67%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (14%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 0 | 3 (21%) | |

| Susceptible | 4 (33%) | 4 (80%) | 9 (64%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 4 | 10 | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Resistant | 8 (62%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (24%) |

| Susceptible | 5 (38%) | 4 (50%) | 13 (76%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Antibiotic . | Susceptibility . | CP-CRE (n = 14) . | Non-CP CRE (n = 9) . | Unconfirmed CRE (n = 18) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | Resistant | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) |

| Intermediate | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Susceptible | 5 (50%) | 4 (100%) | 8 (73%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| Aztreonam | Resistant | 8 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (67%) |

| Susceptible | 0 | 0 | 3 (33%) | |

| Not tested | 6 | 3 | 9 | |

| Cefepime | Resistant | 11 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (24%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (19%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 4 (50%) | 9 (56%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | Resistant | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 | |

| Not tested | 11 | 17 | 18 | |

| Ceftriaxone | Resistant | 13 (93%) | 5 (100%) | 14 (93%) |

| Susceptible | 1 (7%) | 0 | 1 (7%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Resistant | 7 (64%) | 1 (14%) | 4 (31%) |

| Susceptible | 4 (36%) | 6 (86%) | 9 (69%) | |

| Not tested | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Colistin | Resistant | 0 | 0 | 1(50%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (33%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 2 (67%) | 1(100%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 11 | 8 | 16 | |

| Ertapenem | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 17 (100%) |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gentamicin | Resistant | 11 (46%) | 0 | 13 (26%) |

| Intermediate | 0 | 0 | 4 (8%) | |

| Susceptible | 3 (54%) | 8 (100%) | 33 (66%) | |

| Not tested | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Imipenem | Resistant | 7 (78%) | 0 | 3 (30%) |

| Intermediate | 2 (22%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 7 (70%) | |

| Not tested | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| Meropenem | Resistant | 12 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 9 (53%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (8%) | 2(25%) | 0 | |

| Susceptible | 0 | 4 (50%) | 8 (47%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Polymyxin/b | Resistant | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 3 (75%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not tested | 10 | 9 | 18 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | Resistant | 12 (100%) | 5 (62%) | 6 (33%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (17%) | |

| Susceptible | 0 (0%) | 0 | 9 (50%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Tobramycin | Resistant | 8 (67%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (14%) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | 0 | 3 (21%) | |

| Susceptible | 4 (33%) | 4 (80%) | 9 (64%) | |

| Not tested | 2 | 4 | 10 | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Resistant | 8 (62%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (24%) |

| Susceptible | 5 (38%) | 4 (50%) | 13 (76%) | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviation: CP-CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates with a carbapenemase gene.

Susceptibility for antibiotics was lowest in CP-CRE isolates. Susceptibility of non–CP-CRE and unconfirmed CRE for ciprofloxacin, cefepime, imipenem, and meropenem were comparable, whereas susceptibility to piperacillin-tazobactam was observed in 50% of unconfirmed CRE but not in CP-CRE or non–CP-CRE isolates (Table 2).

Thirty-four patients were receiving empiric antibiotic therapy on the date of culture collection. Among these, only 6 were prescribed an antibiotic to which the CRE isolate was confirmed to be susceptible in vitro.

Mortality

In this cohort, 30-day mortality was 13.7% (n = 7) (95% CI 5.7%, 26.3%) and 90-day mortality was 17.7% (n = 9) (95% CI, 8.4–30.9). Among patients with infection, 90-day mortality was 28.5%. The majority of the children who died had major comorbidities (7 of 9). The clinical and microbiologic characteristics of the 9 patients who died are summarized in Table 3. Importantly, 8 of the 9 patients who died met criteria for infection with CRE. The time from the date of culture collection to death ranged from 1 to 57 days, with a median of 12 days.

| Patient . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . | Patient 7 . | Patient 8 . | Patient 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 6 mo | 7 y | 1 mo | 2 y | 16 y | 10 mo | 3 wk | 6 mo | 4 mo |

| Sex | M | M | F | M | M | F | F | F | F |

| Comorbid conditions | Immune- deficiency | Leukemia HSCT | Malignancy | Cirrhosis | Congestive heart failure | Pulmonary disease | Pulmonary disease | None | None |

| Hospital days until positive culture | 17 | 53 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 23 | 19 | 21 |

| Preceding antibiotics (total days) | CTX (2) CFP (8) TZP (4) AMP (7) | CTX (3) CFP (14) MEM (4) | SXT (26) TZP (8) MEM (5) | TZP (1) | None | None | None | SAMa | CTXa |

| Culture source | Respiratory | Urine | Respiratory | Blood | Abdominal | Respiratory | Blood | Respiratory | Respiratory |

| Infection | Colonization | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection |

| Species | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Proteus mirabilis | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Enterobacter spp |

| Carbapenemase | NDM-1 | Non-CP CRE | KPC-2 | OXA-232 | Non-CP CRE | KPC negative | KPC-2 | Not tested | KPC negative |

| Antibiotic therapy for 30 d after culture (total days) a unkown | CFP (3) MEM (17) CST (11) PMB (1) | MEM (21) CIP (11) | PMB (1) CZA (7) MEM (3) SXT (7) | MEM (5) TOB (2) AMK (2) CZA (6) CST (5) SXT (6) | CFP (1) | TZPa | CST (3) | GEN (6) MEM (4) | GEN (3) |

| Days from positive culture to death | 16 | 50 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 57 | 30 |

| Patient . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . | Patient 7 . | Patient 8 . | Patient 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 6 mo | 7 y | 1 mo | 2 y | 16 y | 10 mo | 3 wk | 6 mo | 4 mo |

| Sex | M | M | F | M | M | F | F | F | F |

| Comorbid conditions | Immune- deficiency | Leukemia HSCT | Malignancy | Cirrhosis | Congestive heart failure | Pulmonary disease | Pulmonary disease | None | None |

| Hospital days until positive culture | 17 | 53 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 23 | 19 | 21 |

| Preceding antibiotics (total days) | CTX (2) CFP (8) TZP (4) AMP (7) | CTX (3) CFP (14) MEM (4) | SXT (26) TZP (8) MEM (5) | TZP (1) | None | None | None | SAMa | CTXa |

| Culture source | Respiratory | Urine | Respiratory | Blood | Abdominal | Respiratory | Blood | Respiratory | Respiratory |

| Infection | Colonization | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection |

| Species | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Proteus mirabilis | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Enterobacter spp |

| Carbapenemase | NDM-1 | Non-CP CRE | KPC-2 | OXA-232 | Non-CP CRE | KPC negative | KPC-2 | Not tested | KPC negative |

| Antibiotic therapy for 30 d after culture (total days) a unkown | CFP (3) MEM (17) CST (11) PMB (1) | MEM (21) CIP (11) | PMB (1) CZA (7) MEM (3) SXT (7) | MEM (5) TOB (2) AMK (2) CZA (6) CST (5) SXT (6) | CFP (1) | TZPa | CST (3) | GEN (6) MEM (4) | GEN (3) |

| Days from positive culture to death | 16 | 50 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 57 | 30 |

Abbreviations: AMK, amikacin; CFP, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CST, colistin; CZA, ceftazidime; GEN, gentamicin; MEM, meropenem; PMB, polymyxin B; TOB, tobramycin; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; SAM, sulbactam-ampicillin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

aDuration of therapy unknown.

| Patient . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . | Patient 7 . | Patient 8 . | Patient 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 6 mo | 7 y | 1 mo | 2 y | 16 y | 10 mo | 3 wk | 6 mo | 4 mo |

| Sex | M | M | F | M | M | F | F | F | F |

| Comorbid conditions | Immune- deficiency | Leukemia HSCT | Malignancy | Cirrhosis | Congestive heart failure | Pulmonary disease | Pulmonary disease | None | None |

| Hospital days until positive culture | 17 | 53 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 23 | 19 | 21 |

| Preceding antibiotics (total days) | CTX (2) CFP (8) TZP (4) AMP (7) | CTX (3) CFP (14) MEM (4) | SXT (26) TZP (8) MEM (5) | TZP (1) | None | None | None | SAMa | CTXa |

| Culture source | Respiratory | Urine | Respiratory | Blood | Abdominal | Respiratory | Blood | Respiratory | Respiratory |

| Infection | Colonization | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection |

| Species | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Proteus mirabilis | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Enterobacter spp |

| Carbapenemase | NDM-1 | Non-CP CRE | KPC-2 | OXA-232 | Non-CP CRE | KPC negative | KPC-2 | Not tested | KPC negative |

| Antibiotic therapy for 30 d after culture (total days) a unkown | CFP (3) MEM (17) CST (11) PMB (1) | MEM (21) CIP (11) | PMB (1) CZA (7) MEM (3) SXT (7) | MEM (5) TOB (2) AMK (2) CZA (6) CST (5) SXT (6) | CFP (1) | TZPa | CST (3) | GEN (6) MEM (4) | GEN (3) |

| Days from positive culture to death | 16 | 50 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 57 | 30 |

| Patient . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . | Patient 7 . | Patient 8 . | Patient 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 6 mo | 7 y | 1 mo | 2 y | 16 y | 10 mo | 3 wk | 6 mo | 4 mo |

| Sex | M | M | F | M | M | F | F | F | F |

| Comorbid conditions | Immune- deficiency | Leukemia HSCT | Malignancy | Cirrhosis | Congestive heart failure | Pulmonary disease | Pulmonary disease | None | None |

| Hospital days until positive culture | 17 | 53 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 23 | 19 | 21 |

| Preceding antibiotics (total days) | CTX (2) CFP (8) TZP (4) AMP (7) | CTX (3) CFP (14) MEM (4) | SXT (26) TZP (8) MEM (5) | TZP (1) | None | None | None | SAMa | CTXa |

| Culture source | Respiratory | Urine | Respiratory | Blood | Abdominal | Respiratory | Blood | Respiratory | Respiratory |

| Infection | Colonization | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection | Infection |

| Species | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Proteus mirabilis | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Enterobacter spp | Enterobacter spp |

| Carbapenemase | NDM-1 | Non-CP CRE | KPC-2 | OXA-232 | Non-CP CRE | KPC negative | KPC-2 | Not tested | KPC negative |

| Antibiotic therapy for 30 d after culture (total days) a unkown | CFP (3) MEM (17) CST (11) PMB (1) | MEM (21) CIP (11) | PMB (1) CZA (7) MEM (3) SXT (7) | MEM (5) TOB (2) AMK (2) CZA (6) CST (5) SXT (6) | CFP (1) | TZPa | CST (3) | GEN (6) MEM (4) | GEN (3) |

| Days from positive culture to death | 16 | 50 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 57 | 30 |

Abbreviations: AMK, amikacin; CFP, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CST, colistin; CZA, ceftazidime; GEN, gentamicin; MEM, meropenem; PMB, polymyxin B; TOB, tobramycin; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; SAM, sulbactam-ampicillin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

aDuration of therapy unknown.

Of the 9 patients who died, 6 were younger than age of 1 year. K. pneumoniae was isolated from 5 patients and Enterobacter species complex were isolated from 3. Carbapenemases were detected in 4 isolates, all of which were from K. pneumoniae. The source of culture was respiratory tract in 5 patients, blood in 2 patients, and urine and abdominal fluid from 1 patient each. Six of 9 patients who died had received antibiotics during their hospitalization before the culture, including 2 who were previously treated with a carbapenem.

Four of 9 deceased patients received empiric antibiotic therapy on the date of culture acquisition, of which only 1 was confirmed to be susceptible in vitro, whereas 5 of the 42 patients who survived received an effective antibiotic from the date of acquisition. All 9 fatal cases had been subsequently prescribed antibiotics, 3 of whom received at least 1 antibiotic to which the culture was confirmed to be susceptible. The 1 patient who received effective empiric antibiotic therapy and died had true infection, whereas 3 of the 5 who survived were considered colonized.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe the clinical, microbiologic, and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales among pediatric patients from 2 nationwide, prospective cohorts (CRACKLE-1 and -2). We identified pediatric patients with CRE from clinical cultures in 18 hospitals, representing a geographically widespread sample of U.S. hospitals. Our data demonstrate the emergence of CRE in children in multiple regions of the united States and also highlights that CP-CRE, in particular, remain uncommon in this patient population.

Previous case-control studies and case series evaluating pediatric CRE in children have identified similar risk factors for CRE acquisition in children and adults, including exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, residence in a long-term care facility, admission to an ICU, immunocompromising conditions, history of mechanical ventilation, and prior surgery [12, 13, 14]. Our findings confirm most of these observations. That the median time from admission to the date of index culture was 11 days could indicate that many pediatric CRE isolates were hospital-acquired.

A large proportion of patients in this cohort were younger than age 2 years, including more than one-fifth who were admitted at birth. Although the study did not report on gestational age, that hospital stay exceeded 5 weeks in most of these cases could indicate that many of these infants were born prematurely. Some of the earliest reports of CRE infection in children in other countries were identified from local outbreaks in neonatal ICUs [19, 20]. Our study suggests that admission or exposure to neonatal ICUs may be a particular risk factor for pediatric CRE in the United States as well. Larger studies are required to determine whether this risk is due to emergence of specific clones in the pediatric population, healthcare exposure while in the neonatal ICU, maternal colonization with CRE, prenatal maternal broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure, or a combination of these factors.

Another notable finding of this study is the relative overrepresentation of Black and Hispanic children in our cohort compared with the overall patient cohort described in CRACKLE-1 and -2. Cases were scattered and reported in 14 of the 18 hospitals. It is unclear whether this is due to selection bias in the study populations or if it may reflect underlying healthcare disparities.

There were significant differences in the microbiologic and molecular profiles of CRE between children and adults within the CRACKLE cohorts. The most common species isolated from children was Enterobacter cloacae, representing 41% of cultures, followed by K. pneumoniae at 27%. The proportion of K. pneumoniae among children was significantly lower than the 59% reported in adult patients in the CRACKLE-2 cohort [16].

Furthermore, although 61% of adult isolates in the CRACKLE-2 cohort were carbapenemase-producing CRE, carbapenemase genes were detected in only 29% of pediatric isolates tested. This may in part reflect the aforementioned differences in Enterobacterales species distribution between adult and pediatric patients because KPC carbapenemases have classically been associated with K. pneumoniae.

The relative predominance of Enterobacter species in the pediatric cohort has been similarly observed in a previous study of pediatric CRE in which Enterobacter constituted 57% of isolates compared with 25% for K. pneumoniae [14]. In that study, 8 of 23 total isolates tested were carbapenemase positive. To further investigate the observed difference in species prevalence between pediatric and adult patients, a more extensive analysis of intestinal colonization in pediatric and adult populations as well as analysis of exposure to different healthcare settings (eg, hemodialysis, nursing homes) may be required. Microbiome species prevalence and diversity likely differs in children and adults in the CRACKLE cohorts because microbial colonization expands rapidly following birth, microbiome composition is particularly variable during infancy, and many patients in our cohort were younger than age 2 years.

Similar to the adult patients in the CRACKLE-2 cohort, a significant percentage of CDC-defined CRE were not carbapenem resistant on repeat testing in a central research laboratory. At this point, it is unclear whether these unconfirmed CRE are isolates with ertapenem minimum inhibitory concentrations close to the breakpoints, and hence exhibit variability in repeat susceptibility testing. Alternatively automated carbapenem susceptibility with ertapenem testing may be error prone. In line with this hypothesis, susceptibility to meropenem and imipenem was higher in non–CP-CRE and unconfirmed CRE when compared with CP-CRE isolates. The prevalence of unconfirmed CRE from CRACKLE-1 is unknown because the non–carbapenemase-producing isolates from this cohort did not undergo repeat, confirmatory susceptibility testing. The clinical significance of unconfirmed CRE remains uncertain.

The mortality in this pediatric cohort was lower than that described in the respective adult cohort, but still alarming at 13.7% at 30 days and 17.7% at 90 days. This compares with 30-day mortality of 24% and 90-day mortality of 31% in the entire CRACKLE-2 cohort. Most pediatric patients who died met our criteria for CRE infection, indicating that the CRE infection may indeed have contributed to the lethal outcome. Chiotos et al previously described 30-day mortality of 8.3% in a cohort of 72 children with CRE, with a relative risk for mortality of 6.0 compared with controls in a matched cohort [14]. The higher proportion of neonates in our cohort may explain the higher mortality rate we observed. In critically ill neonates requiring ICU-level care, it is difficult to assess all-cause versus attributable mortality. Notably, although Enterobacter spp complex constituted a plurality of CRE isolates recovered from pediatric patients overall, in 5 of the 9 patients with lethal outcome, K. pneumoniae was recovered from culture, of which 4 were carbapenemase-producing.

Antibiotic resistance was extensive among all isolates, including those few tested against broad-spectrum antibiotics such as polymyxin and ceftazidime-avibactam. It is noteworthy that a majority of patients did not empirically receive an antibiotic to which the culture was susceptible, and of those patients who died, only 1 of 9 patients received an antibiotic to which the isolate was susceptible on the day the culture was obtained.

Even though ceftazidime-avibactam is now approved in children older than 3 months of age, approximately one-third of the patients in this study would not have met age eligibility criteria for Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for treatment with this drug [21]. Similarly, the recent Food and Drug Administration approval of cefiderocol for complicated urinary tract infections and hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia as part of ongoing efforts to address antimicrobial resistance is limited to patients older than 18 years. These data underscore the need for clinical trials that include children so that more therapeutic options become available to treat CRE in children. These data also highlight the need for continued antibiotic stewardship to slow the progression of antimicrobial resistance, as well as robust infection control measures to reduce nosocomial acquisition of CRE.

This study was relatively small compared with the adult cohort and is limited by potential sampling bias because it was restricted to tertiary care centers participating in the CRACKLE studies, which could have influenced the observed geographic distribution and demographic profile of the cohort. Although the CRACKLE-1 study design was initially limited to patients with carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, the effect was minor because only 6 K. pneumoniae isolates in total were ultimately derived from this cohort. In CRACKLE-1, the data about prior antibiotic usage were limited to within 14 days before the index culture, so we could not examine possible antibiotic exposure in that cohort before that point in time. Additionally, the study lacked a control group of hospitalized pediatric patients without CRE. Because of the design of the original CRACKLE study, which anticipated a mostly adult population, clearly defined pediatric-specific comorbidities including prematurity were not documented, nor could we assess for maternal CRE colonization or maternal broad-spectrum antibiotic use among the significant number of neonatal patients. Last, our database lacks specific details regarding reason for hospitalization or cause of death, limiting our ability to make definitive conclusions regarding these clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank all of the MDRO investigators for their contributions to the study, and Yohei Doi, MD, PhD at the University of Pittsburgh, Toshimitsu Hamasaki, PhD, at George Washington University, and Henry Chambers, MD, at UCSF for careful review of this paper.

Patient Consent Statement for CRACKLE-1 and CRACKLE-2. The Consortium on Resistance Against Carbapenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Other Enterobacteriaceae (CRACKLE-1) is a prospective multicenter consortium that includes the participation of 18 hospital study sites that are part of 8 healthcare systems predominantly located in the Great Lakes region of the United States. Initially, the consortium included patients with only carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae. Since October 2014, other CRE species were also included. The second Consortium on Resistance Against Carbapenems in Klebsiella and other Enterobacteriaceae (CRACKLE-2) is also a prospective, observational, multicenter study with consecutive enrollment of hospitalized patients. Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–defined CRE was isolated in a clinical culture from any anatomic site during hospitalization; surveillance cultures were not eligible. There was no age exclusion. The first qualifying culture episode during the first admission for each unique patient enrolled during the study period (30 April 2016–31 August 2017) with an available Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–defined CRE isolate was included. Twenty-six study sites with 49 U.S. hospitals in 15 states and the District of Columbia contributed patients. The 49 study hospitals are compared with 6282 U.S. hospitals in Supplementary Table 1 (PMID 32151332). The final study size was derived by inclusion of all eligible patients within the study period. Both the CRACKLE-1 and -2 studies were approved by the institutional review boards of all the health systems. The study operated under a waiver of informed consent, consistent with CFR Title 45 part 46.116(d), and did not involve direct interaction with human subjects. The CRACKLE-2 trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT03646227.

References

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1AI104681. W. C. H. is a member of an endpoint adjudication committee for Pfizer and has served as an advisory board member for ADMA Biologics. He has common stock in Pfizer, Bristol Meyers Squibb, and Zimmer Biomet. D. v. D. was supported by R01AI143910 from NIAID. B. C. F. was supported by US Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award 5I01 BX00374. She is an attending at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs—Northport VA Medical Center, Northport, NY. D. v. D. has received personal fees from Achaogen, Allergan, Astellas, Neumedicine, T2biosystems, Roche, Merck, Karius, Entasis, Wellspring, Qpex, Pfizer, Utility, and Union; they are all outside the submitted work. The contents is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the views of the National Institute of Health, the VA, or the United States Government. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

- antibiotics

- polymerase chain reaction

- adult

- censuses

- child

- comorbidity

- enterobacter

- epidemiology, molecular

- genes

- inpatients

- klebsiella pneumoniae

- pediatrics

- mortality

- public health medicine

- rales

- mechanical ventilation

- electronic medical records

- health care systems

- microbial colonization

- carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae infections

- carbapenem resistance

- whole genome sequencing

Comments