-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Manu P Bilsen, Rosa M H Jongeneel, Caroline Schneeberger, Tamara N Platteel, Cees van Nieuwkoop, Lona Mody, Jeffrey M Caterino, Suzanne E Geerlings, Bela Köves, Florian Wagenlehner, Simon P Conroy, Leo G Visser, Merel M C Lambregts, Definitions of Urinary Tract Infection in Current Research: A Systematic Review, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 10, Issue 7, July 2023, ofad332, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad332

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Defining urinary tract infection (UTI) is complex, as numerous clinical and diagnostic parameters are involved. In this systematic review, we aimed to gain insight into how UTI is defined across current studies. We included 47 studies, published between January 2019 and May 2022, investigating therapeutic or prophylactic interventions in adult patients with UTI. Signs and symptoms, pyuria, and a positive urine culture were required in 85%, 28%, and 55% of study definitions, respectively. Five studies (11%) required all 3 categories for the diagnosis of UTI. Thresholds for significant bacteriuria varied from 103 to 105 colony-forming units/mL. None of the 12 studies including acute cystitis and 2 of 12 (17%) defining acute pyelonephritis used identical definitions. Complicated UTI was defined by both host factors and systemic involvement in 9 of 14 (64%) studies. In conclusion, UTI definitions are heterogeneous across recent studies, highlighting the need for a consensus-based, research reference standard for UTI.

Urinary tract infection (UTI) refers to a plethora of clinical phenotypes, including cystitis, pyelonephritis, prostatitis, urosepsis, and catheter-associated UTI (CA-UTI) [1, 2]. In both clinical practice and in research, the diagnosis of UTI is based on a multitude of clinical signs and symptoms and diagnostic tests. Signs and symptoms can be further subdivided into (1) lower urinary tract symptoms, such as dysuria, frequency, and urgency; (2) systemic signs and symptoms, such as fever; and (3) nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as nausea and malaise. Commonly used diagnostic tests include urine dipstick for determining the presence of leukocyte esterase and nitrites, microscopy or flow cytometry for quantification of pyuria, and urine and blood cultures.

When defining and diagnosing UTI, numerous combinations of signs, symptoms, and outcomes of diagnostic tests are possible, and this diversity is reflected in various research guidelines. For drug development and approval purposes, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [3] and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [4, 5] have developed guidelines for clinical trials evaluating antimicrobials for the treatment of UTI, summarized in Table 1. These guidelines provide definitions for uncomplicated UTI, complicated UTI, and acute pyelonephritis. McGeer et al [6] have developed research guidelines for studies in long-term care facilities (LTCFs). Clinical practice guidelines include the Infectious Diseases Society of America (currently being updated) [7] and European Association of Urology [8] guidelines. It is important to distinguish between research guidelines and clinical practice guidelines as the latter are meant for treatment recommendations, and the definitions in these clinical guidelines are generally based on often limited diagnostic information available when assessing a patient in the clinical, near-patient setting.

European Medicines Agency and US Food and Drug Administration Definitions of Uncomplicated and Complicated Urinary Tract Infection

| Category . | uUTI . | cUTI . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMA . | FDA . | EMA . | FDA . | |

| Symptoms | A minimum number of symptoms, such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria | ≥2 of dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain (lower abdominal discomfort is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) Patients should not have signs or symptoms of systemic illness such as fever >38°C, shaking chills, or other manifestations suggestive of cUTI | A minimum number of signs/symptoms compatible with an ongoing process in the urinary tract, such as flank or pelvic pain, CVA tenderness, dysuria, frequency, or urgency | ≥2 of chills or rigors or warmth associated with fever (>38°C), flank or pelvic pain, dysuria, frequency or urgency, CVA tenderness (malaise is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) |

| Host factors | Female patients | Female patients with normal anatomy of the urinary tract | ≥1 of indwelling catheter, urinary retention, obstruction, neurogenic bladder AP is mentioned separately from cUTI, but it is not further defined | ≥1 of indwelling urinary catheter, neurogenic bladder, obstructive uropathy, azotemia caused by intrinsic renal disease, urinary retention (including retention caused by BPH) AP is a subset of cUTI regardless of underlying abnormalities of the urinary tract |

| Pyuria | >10 leukocytes/μL | “A microscopic evaluation for pyuria or dipstick analysis for leukocytes, nitrites or a catalase test should be performed” | >10 leukocytes/μL | Urine dipstick positive for leukocyte esterase or >10 leukocytes/μL |

| Bacteriuria | >105 CFU/mL of a single relevant pathogen | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria | >105 CFU/mL of a single or no more than 2 relevant pathogens | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria |

| Category . | uUTI . | cUTI . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMA . | FDA . | EMA . | FDA . | |

| Symptoms | A minimum number of symptoms, such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria | ≥2 of dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain (lower abdominal discomfort is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) Patients should not have signs or symptoms of systemic illness such as fever >38°C, shaking chills, or other manifestations suggestive of cUTI | A minimum number of signs/symptoms compatible with an ongoing process in the urinary tract, such as flank or pelvic pain, CVA tenderness, dysuria, frequency, or urgency | ≥2 of chills or rigors or warmth associated with fever (>38°C), flank or pelvic pain, dysuria, frequency or urgency, CVA tenderness (malaise is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) |

| Host factors | Female patients | Female patients with normal anatomy of the urinary tract | ≥1 of indwelling catheter, urinary retention, obstruction, neurogenic bladder AP is mentioned separately from cUTI, but it is not further defined | ≥1 of indwelling urinary catheter, neurogenic bladder, obstructive uropathy, azotemia caused by intrinsic renal disease, urinary retention (including retention caused by BPH) AP is a subset of cUTI regardless of underlying abnormalities of the urinary tract |

| Pyuria | >10 leukocytes/μL | “A microscopic evaluation for pyuria or dipstick analysis for leukocytes, nitrites or a catalase test should be performed” | >10 leukocytes/μL | Urine dipstick positive for leukocyte esterase or >10 leukocytes/μL |

| Bacteriuria | >105 CFU/mL of a single relevant pathogen | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria | >105 CFU/mL of a single or no more than 2 relevant pathogens | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria |

In the EMA guidelines, bacteriuria definitions were mentioned in the description of the microbiological intention-to-treat population. In the FDA guidelines, they were also mentioned separately, under clinical microbiology considerations.

Abbreviations: AP, acute pyelonephritis; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; CFU, colony-forming units; cUTI, complicated urinary tract infection; CVA, costovertebral angle; EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, United States Food and Drug Administration; uUTI, uncomplicated urinary tract infection.

European Medicines Agency and US Food and Drug Administration Definitions of Uncomplicated and Complicated Urinary Tract Infection

| Category . | uUTI . | cUTI . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMA . | FDA . | EMA . | FDA . | |

| Symptoms | A minimum number of symptoms, such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria | ≥2 of dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain (lower abdominal discomfort is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) Patients should not have signs or symptoms of systemic illness such as fever >38°C, shaking chills, or other manifestations suggestive of cUTI | A minimum number of signs/symptoms compatible with an ongoing process in the urinary tract, such as flank or pelvic pain, CVA tenderness, dysuria, frequency, or urgency | ≥2 of chills or rigors or warmth associated with fever (>38°C), flank or pelvic pain, dysuria, frequency or urgency, CVA tenderness (malaise is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) |

| Host factors | Female patients | Female patients with normal anatomy of the urinary tract | ≥1 of indwelling catheter, urinary retention, obstruction, neurogenic bladder AP is mentioned separately from cUTI, but it is not further defined | ≥1 of indwelling urinary catheter, neurogenic bladder, obstructive uropathy, azotemia caused by intrinsic renal disease, urinary retention (including retention caused by BPH) AP is a subset of cUTI regardless of underlying abnormalities of the urinary tract |

| Pyuria | >10 leukocytes/μL | “A microscopic evaluation for pyuria or dipstick analysis for leukocytes, nitrites or a catalase test should be performed” | >10 leukocytes/μL | Urine dipstick positive for leukocyte esterase or >10 leukocytes/μL |

| Bacteriuria | >105 CFU/mL of a single relevant pathogen | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria | >105 CFU/mL of a single or no more than 2 relevant pathogens | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria |

| Category . | uUTI . | cUTI . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMA . | FDA . | EMA . | FDA . | |

| Symptoms | A minimum number of symptoms, such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria | ≥2 of dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain (lower abdominal discomfort is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) Patients should not have signs or symptoms of systemic illness such as fever >38°C, shaking chills, or other manifestations suggestive of cUTI | A minimum number of signs/symptoms compatible with an ongoing process in the urinary tract, such as flank or pelvic pain, CVA tenderness, dysuria, frequency, or urgency | ≥2 of chills or rigors or warmth associated with fever (>38°C), flank or pelvic pain, dysuria, frequency or urgency, CVA tenderness (malaise is also mentioned in another section of the guidance document) |

| Host factors | Female patients | Female patients with normal anatomy of the urinary tract | ≥1 of indwelling catheter, urinary retention, obstruction, neurogenic bladder AP is mentioned separately from cUTI, but it is not further defined | ≥1 of indwelling urinary catheter, neurogenic bladder, obstructive uropathy, azotemia caused by intrinsic renal disease, urinary retention (including retention caused by BPH) AP is a subset of cUTI regardless of underlying abnormalities of the urinary tract |

| Pyuria | >10 leukocytes/μL | “A microscopic evaluation for pyuria or dipstick analysis for leukocytes, nitrites or a catalase test should be performed” | >10 leukocytes/μL | Urine dipstick positive for leukocyte esterase or >10 leukocytes/μL |

| Bacteriuria | >105 CFU/mL of a single relevant pathogen | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria | >105 CFU/mL of a single or no more than 2 relevant pathogens | ≥105 CFU/mL of a single species of bacteria |

In the EMA guidelines, bacteriuria definitions were mentioned in the description of the microbiological intention-to-treat population. In the FDA guidelines, they were also mentioned separately, under clinical microbiology considerations.

Abbreviations: AP, acute pyelonephritis; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; CFU, colony-forming units; cUTI, complicated urinary tract infection; CVA, costovertebral angle; EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, United States Food and Drug Administration; uUTI, uncomplicated urinary tract infection.

While the aforementioned research guidelines overlap in the sense that they all include a combination of symptoms and evidence of pyuria and/or bacteriuria in the definition of UTI, they also differ. For instance, none of these guidelines include the same set (or minimum number) of symptoms for the diagnosis of UTI. Moreover, the definition of complicated UTI is variable and based on either systemic signs and symptoms or the presence of host factors predisposing the patient to a complicated clinical course (eg, functional or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract).

It is probable that this wide range of possible definitions and different research guidelines pose problems for researchers conducting studies with patients with UTI. A uniform research definition increases homogeneity between studies, which is important for the interpretation, synthesis, and comparability of results, and mitigates the risk of misclassification bias. This is especially relevant in an era of rising antimicrobial resistance, in which novel antimicrobials are being investigated in large randomized controlled trials. The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate how UTI is defined in current studies, and to which extent these definitions differ between studies.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [9].

Eligibility Criteria

Studies published between January 2019 and May 2022, investigating any therapeutic or prophylactic intervention in adults with (recurrent) UTI, were eligible for inclusion. Given the fact that definitions tend to change over time, this time frame was chosen to reflect the most recent consensus. In addition, updated FDA and EMA guidelines were published in 2019. We excluded studies concerning only prostatitis, CA-UTI, pericatheter or perioperative prophylaxis, or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Studies investigating patients with spinal cord injury or neurogenic bladder were also excluded, because separate UTI definitions are mostly used for patients who are unable to experience (or have altered perception of) lower urinary tract symptoms. Finally, we excluded systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and studies published in non-English-language journals

Search Strategy

Multiple electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane library) were searched on 16 May 2022. Our search strategy was constructed by a research librarian and was based on a population, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO)–style approach. We applied language and publication year filters as described above and used an “article” type filter for clinical trials. The complete search strategy is provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Covidence software was used for screening and data extraction. References were imported and duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening, full-text screening and data extraction were performed by 2 independent reviewers (M. P. B. and R. M. H. J.). In case of disagreement, a third researcher was consulted (M. M. C. L.) and a final decision was based on consensus.

For each study, the following data were collected: study design, setting, population, intervention, and the type of UTI under investigation. Criteria for the definition of UTI were subdivided into 3 categories: signs and symptoms, urinalysis, and urine culture. For each of these categories, we assessed whether they were required or conditionally required (ie, dependent on the presence of other categories) for the diagnosis of UTI. If categories were not mentioned, or if they were only required for a secondary outcome or definition, they were considered as not required. Definitions were derived from eligibility criteria unless definitions were explicitly stated elsewhere. For signs and symptoms, additional data were collected on minimum number of symptoms and symptom specification (eg, if fever and frequency were further defined). Moreover, we recorded which symptoms were part of the definition of acute cystitis, acute pyelonephritis, and UTI if a clinical phenotype was not mentioned (henceforth described as UTI–phenotype not specified). For the urinalysis category, we extracted which methods were used for determining pyuria, which cutoff values were applied, and whether nitrites were part of the UTI definition. Regarding the urine culture category, we recorded the cutoff value for colony-forming units (CFU)/mL and the maximum number of uropathogens. For all 3 categories, we assessed whether study definitions met FDA and EMA guideline requirements. Concerning complicated UTI, we collected the same components of the definition as described above, but we also assessed whether the definition was based on host factors, systemic involvement, or a combination of both. Finally, we compared definitions between studies, stratified per UTI type. No risk of bias assessment was performed as we studied definitions instead of outcomes. Data are summarized as proportions.

RESULTS

Study Selection and Study Characteristics

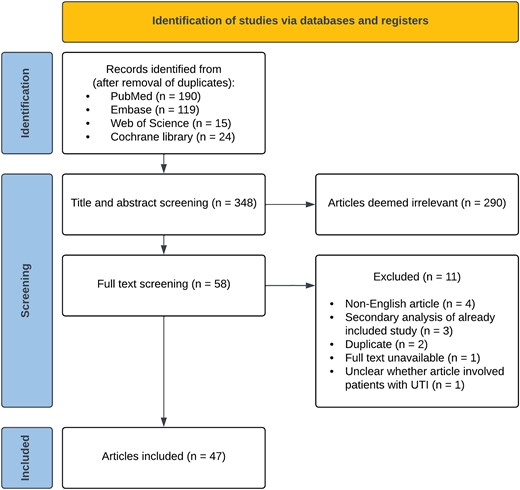

The study selection process is summarized in a PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). We screened 348 reports published between January 2019 and May 2022. Studies that were excluded during title and abstract screening (n = 290) mainly involved patients with CA-UTI or conditions other than UTI (eg, interstitial cystitis), or investigated pericatheter or perioperative prophylaxis. During full-text screening, 7 non-English articles and secondary analyses of articles already included in the study using our search criteria were excluded. A total of 47 randomized controlled trials and cohort studies with a median of 145 participants were included [2–56].

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart of the study selection process. Abbreviation: UTI, urinary tract infection.

Thirty-one studies (66%) investigated antimicrobials for the treatment of UTI, and 15 (32%) evaluated antimicrobial prophylaxis for recurrent UTI. Sixteen studies (34%) only included women, 4 studies (9%) only included men, and 27 studies (57%) included both. Participants were hospitalized in 25 studies (53%) and treated through an outpatient or primary care clinic in 22 studies (47%). None of the included studies were conducted in LTCFs. Twelve studies (26%) included acute cystitis, 16 (34%) included acute pyelonephritis, and 13 (28%) included UTI–phenotype not specified. A table containing details of all included studies is provided in Supplementary Material 2.

UTI Definition and Heterogeneity

Table 2 shows how UTI was defined across the included studies. In 11 studies (23%) the definition consisted of only signs and symptoms, in 16 studies (34%) the definition consisted of both signs and symptoms and a positive urine culture, and in 5 studies (11%) all 3 components (signs and symptoms, the presence of pyuria, and a positive urine culture) were required for the diagnosis of UTI. None of the studies investigating acute cystitis (n = 12) or UTI–phenotype not specified (n = 13) included the same set of symptoms and diagnostic criteria in their definition. Of the studies defining acute pyelonephritis, 2 (17%) used identical definitions.

| Categories of UTI Definition (n = 47) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Required | 40 (85) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 6 (13) |

| Signs and symptoms specified | 34/40 (85) |

| Minimum number of symptoms specified | 24/40 (60) |

| Pyuria | |

| Required | 13 (28) |

| Conditionally required | 4 (9) |

| Not required | 30 (64) |

| Method of establishing pyuria specified | 14/17 (82) |

| Dipstick only | 2 (14) |

| Quantification only | 4 (29) |

| Both methods allowed | 8 (57) |

| Cutoff for pyuria specified | 12/12 (100) |

| >5 leukocytes/HPF | 2 (17) |

| >10 leukocytes/µL or >10 leukocytes/HPF | 10 (83) |

| Urine culture | |

| Required | 26 (55) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 20 (43) |

| Cutoff for CFU/mL specified | 19/27 (70) |

| >103 CFU/mL | 8 (42) |

| >104 CFU/mL | 4 (21) |

| >105 CFU/mL | 7 (37) |

| Maximum No. of uropathogens specified | 4/27 (15) |

| Urine collection method specified | 12/47 (26) |

| Categories of UTI Definition (n = 47) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Required | 40 (85) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 6 (13) |

| Signs and symptoms specified | 34/40 (85) |

| Minimum number of symptoms specified | 24/40 (60) |

| Pyuria | |

| Required | 13 (28) |

| Conditionally required | 4 (9) |

| Not required | 30 (64) |

| Method of establishing pyuria specified | 14/17 (82) |

| Dipstick only | 2 (14) |

| Quantification only | 4 (29) |

| Both methods allowed | 8 (57) |

| Cutoff for pyuria specified | 12/12 (100) |

| >5 leukocytes/HPF | 2 (17) |

| >10 leukocytes/µL or >10 leukocytes/HPF | 10 (83) |

| Urine culture | |

| Required | 26 (55) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 20 (43) |

| Cutoff for CFU/mL specified | 19/27 (70) |

| >103 CFU/mL | 8 (42) |

| >104 CFU/mL | 4 (21) |

| >105 CFU/mL | 7 (37) |

| Maximum No. of uropathogens specified | 4/27 (15) |

| Urine collection method specified | 12/47 (26) |

If categories were not mentioned, they were considered as not required. Definitions were derived from eligibility criteria unless definitions were explicitly stated elsewhere. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Abbreviations: CFU, colony-forming units; HPF, high-power field; UTI, urinary tract infection.

| Categories of UTI Definition (n = 47) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Required | 40 (85) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 6 (13) |

| Signs and symptoms specified | 34/40 (85) |

| Minimum number of symptoms specified | 24/40 (60) |

| Pyuria | |

| Required | 13 (28) |

| Conditionally required | 4 (9) |

| Not required | 30 (64) |

| Method of establishing pyuria specified | 14/17 (82) |

| Dipstick only | 2 (14) |

| Quantification only | 4 (29) |

| Both methods allowed | 8 (57) |

| Cutoff for pyuria specified | 12/12 (100) |

| >5 leukocytes/HPF | 2 (17) |

| >10 leukocytes/µL or >10 leukocytes/HPF | 10 (83) |

| Urine culture | |

| Required | 26 (55) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 20 (43) |

| Cutoff for CFU/mL specified | 19/27 (70) |

| >103 CFU/mL | 8 (42) |

| >104 CFU/mL | 4 (21) |

| >105 CFU/mL | 7 (37) |

| Maximum No. of uropathogens specified | 4/27 (15) |

| Urine collection method specified | 12/47 (26) |

| Categories of UTI Definition (n = 47) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Required | 40 (85) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 6 (13) |

| Signs and symptoms specified | 34/40 (85) |

| Minimum number of symptoms specified | 24/40 (60) |

| Pyuria | |

| Required | 13 (28) |

| Conditionally required | 4 (9) |

| Not required | 30 (64) |

| Method of establishing pyuria specified | 14/17 (82) |

| Dipstick only | 2 (14) |

| Quantification only | 4 (29) |

| Both methods allowed | 8 (57) |

| Cutoff for pyuria specified | 12/12 (100) |

| >5 leukocytes/HPF | 2 (17) |

| >10 leukocytes/µL or >10 leukocytes/HPF | 10 (83) |

| Urine culture | |

| Required | 26 (55) |

| Conditionally required | 1 (2) |

| Not required | 20 (43) |

| Cutoff for CFU/mL specified | 19/27 (70) |

| >103 CFU/mL | 8 (42) |

| >104 CFU/mL | 4 (21) |

| >105 CFU/mL | 7 (37) |

| Maximum No. of uropathogens specified | 4/27 (15) |

| Urine collection method specified | 12/47 (26) |

If categories were not mentioned, they were considered as not required. Definitions were derived from eligibility criteria unless definitions were explicitly stated elsewhere. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Abbreviations: CFU, colony-forming units; HPF, high-power field; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms were required for the diagnosis of UTI in 40 studies (85%). Of these, 34 (85%) specified signs and symptoms in the definition. The different signs and symptoms that were included in the definition of acute cystitis, acute pyelonephritis, and UTI–phenotype not specified are highlighted in Table 3. FDA guidelines [4] require a minimum of 2 of the following symptoms for patients with uncomplicated UTI: dysuria, urgency, frequency, and suprapubic pain. Two of 12 studies (17%) met these criteria. Flank pain and/or costovertebral angle tenderness, fever, nausea and/or vomiting, and dysuria were most often included in the definition of acute pyelonephritis. Frequency was not further specified in any study. Perineal and/or prostate pain was part of the definition in 3 of 31 (10%) studies involving men. A specific temperature cutoff for fever was defined in 7 of 17 (65%) studies that included fever in the definition of UTI.

| Symptoms and Signs . | Acute Cystitis (n = 12) . | Acute Pyelonephritis (n = 16)a . | UTI–Phenotype Not Specified (n = 13) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysuria | 9 (75) | 8 (50) | 9 (69) |

| Urgency | 9 (75) | 6 (38) | 7 (54) |

| Frequency | 9 (75) | 7 (44) | 6 (46) |

| Suprapubic pain | 5 (42) | 0 | 6 (46) |

| Macroscopic hematuria | 4 (33) | 0 | 4 (31) |

| Lower abdominal pain | 2 (17) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Perineal/prostate pain | 1 (8) | 0 | 2 (15) |

| Pelvic pain | 0 | 2 (13) | 1 (8) |

| Flank pain or CVA tenderness | 1 (8) | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| New urinary incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Worsening incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Fever | 0 | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| Chills or rigors | 0 | 7 (44) | 0 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 0 | 8 (50) | 0 |

| Symptoms not specified | 3 (25) | 4 (25) | 2 (15) |

| Symptoms and Signs . | Acute Cystitis (n = 12) . | Acute Pyelonephritis (n = 16)a . | UTI–Phenotype Not Specified (n = 13) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysuria | 9 (75) | 8 (50) | 9 (69) |

| Urgency | 9 (75) | 6 (38) | 7 (54) |

| Frequency | 9 (75) | 7 (44) | 6 (46) |

| Suprapubic pain | 5 (42) | 0 | 6 (46) |

| Macroscopic hematuria | 4 (33) | 0 | 4 (31) |

| Lower abdominal pain | 2 (17) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Perineal/prostate pain | 1 (8) | 0 | 2 (15) |

| Pelvic pain | 0 | 2 (13) | 1 (8) |

| Flank pain or CVA tenderness | 1 (8) | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| New urinary incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Worsening incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Fever | 0 | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| Chills or rigors | 0 | 7 (44) | 0 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 0 | 8 (50) | 0 |

| Symptoms not specified | 3 (25) | 4 (25) | 2 (15) |

All symptoms and signs are shown as No. (%). Other symptoms mentioned in studies focusing on acute cystitis or UTI–phenotype not specified were vesical tenesmus (n = 1), malodorous and/or cloudy urine (n = 1), hypogastric pain (n = 1), and nocturia (n = 1). Additional criteria for the definition of acute pyelonephritis not mentioned in the table: elevated serum inflammatory parameters (n = 1), signs of pyelonephritis on ultrasound or computed tomography (n = 1), and hypotension (n = 1).

Abbreviations: CVA, costovertebral angle; UTI, urinary tract infection.

This included all studies investigating acute pyelonephritis, either alone or in conjunction with other types of UTI.

| Symptoms and Signs . | Acute Cystitis (n = 12) . | Acute Pyelonephritis (n = 16)a . | UTI–Phenotype Not Specified (n = 13) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysuria | 9 (75) | 8 (50) | 9 (69) |

| Urgency | 9 (75) | 6 (38) | 7 (54) |

| Frequency | 9 (75) | 7 (44) | 6 (46) |

| Suprapubic pain | 5 (42) | 0 | 6 (46) |

| Macroscopic hematuria | 4 (33) | 0 | 4 (31) |

| Lower abdominal pain | 2 (17) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Perineal/prostate pain | 1 (8) | 0 | 2 (15) |

| Pelvic pain | 0 | 2 (13) | 1 (8) |

| Flank pain or CVA tenderness | 1 (8) | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| New urinary incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Worsening incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Fever | 0 | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| Chills or rigors | 0 | 7 (44) | 0 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 0 | 8 (50) | 0 |

| Symptoms not specified | 3 (25) | 4 (25) | 2 (15) |

| Symptoms and Signs . | Acute Cystitis (n = 12) . | Acute Pyelonephritis (n = 16)a . | UTI–Phenotype Not Specified (n = 13) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysuria | 9 (75) | 8 (50) | 9 (69) |

| Urgency | 9 (75) | 6 (38) | 7 (54) |

| Frequency | 9 (75) | 7 (44) | 6 (46) |

| Suprapubic pain | 5 (42) | 0 | 6 (46) |

| Macroscopic hematuria | 4 (33) | 0 | 4 (31) |

| Lower abdominal pain | 2 (17) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Perineal/prostate pain | 1 (8) | 0 | 2 (15) |

| Pelvic pain | 0 | 2 (13) | 1 (8) |

| Flank pain or CVA tenderness | 1 (8) | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| New urinary incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Worsening incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Fever | 0 | 12 (75) | 2 (15) |

| Chills or rigors | 0 | 7 (44) | 0 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 0 | 8 (50) | 0 |

| Symptoms not specified | 3 (25) | 4 (25) | 2 (15) |

All symptoms and signs are shown as No. (%). Other symptoms mentioned in studies focusing on acute cystitis or UTI–phenotype not specified were vesical tenesmus (n = 1), malodorous and/or cloudy urine (n = 1), hypogastric pain (n = 1), and nocturia (n = 1). Additional criteria for the definition of acute pyelonephritis not mentioned in the table: elevated serum inflammatory parameters (n = 1), signs of pyelonephritis on ultrasound or computed tomography (n = 1), and hypotension (n = 1).

Abbreviations: CVA, costovertebral angle; UTI, urinary tract infection.

This included all studies investigating acute pyelonephritis, either alone or in conjunction with other types of UTI.

Urinalysis and Urine Culture

The presence of pyuria was required for the diagnosis of UTI in 13 of 47 (28%) studies, while both FDA and EMA guidelines [3–5] require pyuria in their definition of UTI. A cutoff for pyuria was specified in 12 studies, of which 10 (83%) applied a cutoff value of >10 leukocytes/µL or >10 leukocytes per high-power field (HPF). None of the included studies required the presence of nitrites for the diagnosis of UTI, although they were conditionally required in 3 studies (6%). A positive urine culture was mandatory for UTI diagnosis in 26 of 47 (55%) studies, of which 12 (55%) were conducted in the primary care or outpatient setting and 14 (56%) involved hospitalized patients. Of the 19 studies that mentioned a cutoff value for CFU/mL, 8 (42%) used a cutoff of 103 CFU/mL. Among all studies, 7 (15%) required a positive urine culture with at least 105 CFU/mL, complying with EMA and FDA guidelines [3–5].

Complicated UTI

We included 14 studies that defined complicated UTI. Three (21%) based their definition on complicating host factors only, 1 (7%) on systemic involvement only, and 9 (64%) on both host factors and systemic involvement. The various host factors included in the definition are provided in Table 4. Male sex was considered a complicating factor in 2 studies (17%).

| Complicated UTI (n = 14) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| How is complicated UTI defined? | |

| Both host factors and systemic involvement | 9 (64) |

| Only host factors | 3 (21) |

| Only systemic involvement | 1 (7) |

| Complicated UTI not further defined | 1 (7) |

| Which host factors are part of complicated UTI criteria?a | |

| Obstructive uropathy | 11 (92) |

| Functional or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract | 10 (83) |

| Indwelling catheter or nephrostomy tube | 9 (75) |

| Intrinsic renal disease | 8 (67) |

| Urinary retention in men due to BPH | 5 (42) |

| Urinary retention in general | 3 (25) |

| Male sex (regardless of urinary retention) | 2 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (17) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (17) |

| Pregnancy | 1 (8) |

| Immunocompromised state | 1 (8) |

| Kidney transplant recipient | 1 (8) |

| Complicated UTI (n = 14) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| How is complicated UTI defined? | |

| Both host factors and systemic involvement | 9 (64) |

| Only host factors | 3 (21) |

| Only systemic involvement | 1 (7) |

| Complicated UTI not further defined | 1 (7) |

| Which host factors are part of complicated UTI criteria?a | |

| Obstructive uropathy | 11 (92) |

| Functional or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract | 10 (83) |

| Indwelling catheter or nephrostomy tube | 9 (75) |

| Intrinsic renal disease | 8 (67) |

| Urinary retention in men due to BPH | 5 (42) |

| Urinary retention in general | 3 (25) |

| Male sex (regardless of urinary retention) | 2 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (17) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (17) |

| Pregnancy | 1 (8) |

| Immunocompromised state | 1 (8) |

| Kidney transplant recipient | 1 (8) |

For the purpose of this table, systemic involvement was defined as the presence of fever and/or rigors in the criteria for diagnosis of complicated UTI.

Abbreviations: BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Host factors were specified in 12 studies; this was used as the denominator for the proportions.

| Complicated UTI (n = 14) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| How is complicated UTI defined? | |

| Both host factors and systemic involvement | 9 (64) |

| Only host factors | 3 (21) |

| Only systemic involvement | 1 (7) |

| Complicated UTI not further defined | 1 (7) |

| Which host factors are part of complicated UTI criteria?a | |

| Obstructive uropathy | 11 (92) |

| Functional or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract | 10 (83) |

| Indwelling catheter or nephrostomy tube | 9 (75) |

| Intrinsic renal disease | 8 (67) |

| Urinary retention in men due to BPH | 5 (42) |

| Urinary retention in general | 3 (25) |

| Male sex (regardless of urinary retention) | 2 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (17) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (17) |

| Pregnancy | 1 (8) |

| Immunocompromised state | 1 (8) |

| Kidney transplant recipient | 1 (8) |

| Complicated UTI (n = 14) . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| How is complicated UTI defined? | |

| Both host factors and systemic involvement | 9 (64) |

| Only host factors | 3 (21) |

| Only systemic involvement | 1 (7) |

| Complicated UTI not further defined | 1 (7) |

| Which host factors are part of complicated UTI criteria?a | |

| Obstructive uropathy | 11 (92) |

| Functional or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract | 10 (83) |

| Indwelling catheter or nephrostomy tube | 9 (75) |

| Intrinsic renal disease | 8 (67) |

| Urinary retention in men due to BPH | 5 (42) |

| Urinary retention in general | 3 (25) |

| Male sex (regardless of urinary retention) | 2 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (17) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 (17) |

| Pregnancy | 1 (8) |

| Immunocompromised state | 1 (8) |

| Kidney transplant recipient | 1 (8) |

For the purpose of this table, systemic involvement was defined as the presence of fever and/or rigors in the criteria for diagnosis of complicated UTI.

Abbreviations: BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Host factors were specified in 12 studies; this was used as the denominator for the proportions.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we demonstrate that UTI definitions used in current research studies are highly heterogeneous in terms of clinical signs and diagnostic tests. In addition, few studies met symptom, pyuria, and urine culture criteria mentioned in existing research guidelines.

Signs and Symptoms

The presence of signs and symptoms was required in the majority of UTI definitions used in the included studies. As symptoms and signs remain the cornerstone of UTI diagnosis, it is noteworthy that 15% of studies did not require signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of UTI and an even greater number of studies did not specify which symptoms and signs needed to be present. Defining specific symptoms may help to mitigate the risk of misclassification. Symptom specification is especially relevant in studies involving older patients with UTI, given the high background prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria and pyuria [57–59]. Most of the studies that did clarify which symptoms were part of the UTI definition included classic UTI-associated symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, and urgency. However, we also found a broad variety of nonspecific manifestations, particularly in studies that did not define the UTI phenotype under investigation. Regardless of the unclear clinical relevance of nonspecific symptoms in UTI, this diversity of symptoms contributes to heterogeneity between studies, which is supported by our finding that few of the included studies used the same set of symptoms to define UTI. Furthermore, in over a third of the included reports, a minimum number of symptoms (for diagnosis) was not mentioned. Given the fact that even classic lower urinary tract symptoms are not 100% specific for UTI, and probability of UTI increases when a combination of symptoms is present, a minimum number of symptoms should be specified [60].

Pyuria and Bacteriuria

Interestingly, less than a third of included studies required the presence of pyuria in the definition of UTI. With the exception of patients with absolute neutropenia and complete obstructive uropathy, pyuria is present in virtually all symptomatic patients with bacteriuria, and its absence has a high negative predictive value for UTI [61–63]. In the included studies, pyuria was rarely quantified and thresholds for significant pyuria were low. A recent study has shown that low pyuria cutoffs should be avoided in older women, as the specificity for UTI is very low in this population [64]. Moreover, studies used different units of measurement interchangeably (ie, identical thresholds were applied for cells/µL and HPF), while results are influenced by different (pre)analytical procedures and previous studies have shown a µL-to-HPF ratio of 5:1 [65]. Be that as it may, quantification of pyuria in UTI studies should be encouraged, and pyuria should be included in the definition of UTI to reduce the risk of misclassification.

As growth of a uropathogen supports the diagnosis of UTI in a symptomatic patient, it is surprising that a positive urine culture was not part of the UTI definition in approximately half of the included studies. Even though urine cultures are not always required in a clinical setting (eg, in primary care), we believe that culture confirmation should at least be encouraged in a research setting. Furthermore, we found that studies used varying cutoffs for significant bacteriuria, ranging from 103 to 105 CFU/mL, while EMA and FDA guidelines both recommend a threshold of 105 CFU/mL. The question remains whether this is the optimal cutoff [66]; colony counts as low as 102 CFU/mL in midstream urine have been found in symptomatic premenopausal woman with Escherichia coli bacteriuria [61, 62].

Complicated UTI

Studies differed widely in their definition of complicated UTI. Since the majority of studies defined complicated UTI based on both complicating host factors and systemic involvement, different clinical phenotypes were included in each study. This not only contributes further to disparities between studies, it also affects the applicability of study results. Moreover, the aforementioned heterogeneity is compounded by the fact that host factors are very diverse in themselves and there is no consensus about which host factors should be included in the definition of complicated UTI. As astutely phrased by James Johnson [67], “it may be time to find a different term than complicated UTI for UTIs that occur in patients with underlying predisposing factors, since this term seems hopelessly mired in ambiguity.” Johansen et al [68]. have proposed a UTI classification system for clinical and research purposes based on clinical phenotype, severity, host factors, and pathogen susceptibility. However, this classification system was not used by any of the included studies in our review. In the Netherlands, the primary care guidelines for UTI have already made a distinction between a UTI in a complicated host versus UTI with systemic involvement [69].

Existing Research Guidelines

We found that few studies met symptom, pyuria, and urine culture criteria mentioned in FDA and EMA guidelines [3–5]. In addition, we identified that studies more frequently based UTI definitions on clinical practice guidelines. The use of clinical practice guidelines in the place of research guidelines seems inappropriate, as clinical guidelines are less stringent than research guidelines and base empirical treatment recommendations on limited diagnostic information. Taken together, our findings imply that a widely accepted, consensus-based gold standard for the diagnosis of UTI is lacking and is much needed in the field of UTI research.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this systematic review include our comprehensive search strategy, including multiple electronic databases, and extracting data from supplemental material, as UTI definitions were frequently only mentioned in a supplemental protocol. Our study has several limitations. For some of the included therapeutic studies, eligibility criteria served as a proxy for the UTI definition, if a definition was not mentioned separately. This might have contributed to additional heterogeneity. For instance, prophylactic studies including patients with recurrent UTI had more frequently provided separate UTI definitions, since these often served as outcome measures. Also, some heterogeneity might be explained by the fact that we included studies that investigated different UTI phenotypes. However, this effect was mitigated by evaluating different UTI phenotypes separately. Another limitation is that we filtered our search strategy on publication date and study type. While expanding the time period would have provided more data, it would not reflect the most recent consensus and would likely have contributed to further heterogeneity, as these studies were published before the FDA and EMA guidance documents. Furthermore, including more observational studies most likely would not have reduced heterogeneity, as these are presumably less likely to follow FDA and EMA guidelines for drug approval. Since we did not find any recent studies that were conducted in LTCFs, and we excluded studies regarding CA-UTI and UTI in spinal cord injury patients, it is unclear how heterogeneous definitions are in these areas. Defining UTI might be even more challenging for these populations and settings.

CONCLUSIONS

UTI definitions differ widely across recent therapeutic and interventional studies. An international consensus-based reference standard is needed to reduce misclassification bias within studies and heterogeneity between studies. To avoid ambiguity, such a reference standard should veer away from the term “complicated UTI” and instead categorize UTI based on systemic involvement, as these are different entities with different treatments. Based on results of this systematic review, our group has initiated an international consensus study to construct a UTI reference standard for research purposes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. Conceptualization and methodology: M. P. B., R. M. H. J., S. P. C., L. G. V., and M. M. C. L. Screening and data extraction: M. P. B. and R. M. H. J. Data analysis: M. P. B. Writing–original draft preparation: M. P. B. and R. M. H. J. Writing–review and editing: M. P. B., R. M. H. J., C. S., T. N. P., C. N., L. M., J. M. C., S. E. G., B. K., F. W., S. P. C., L. G. V., and M. M. C. L. Supervision: M. M. C. L., S. P. C., and L. G. V. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank J. W. Schoones for his contribution to the search strategy.

References

Author notes

M. P. B. and R. M. H. J. contributed equally to this work.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

Comments