-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura Lodolo, Emma Smyth, Yvane Ngassa, Bridget Pickard, Amy M LeClair, Curt G Beckwith, Alysse Wurcel, “To Be Honest, You Probably Would Have to Read It 50 Times”: Stakeholders Views on Using the Opt-Out Approach for Vaccination in Jails, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 10, Issue 5, May 2023, ofad212, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad212

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Despite national guidelines on infectious disease testing and vaccination in prisons, there is heterogeneity on the implementation of these practices in jails. We sought to better understand perspectives on the implementation of opt-out vaccination for infectious diseases in jails by interviewing a broad group of stakeholders involved in infectious diseases vaccination, testing, and treatment in Massachusetts jails.

The research team conducted semistructured interviews with people incarcerated in Hampden County Jail (Ludlow, Massachusetts), clinicians working in jail and community settings, corrections administrators, and representatives from public health, government, and industry between July 2021 and March 2022.

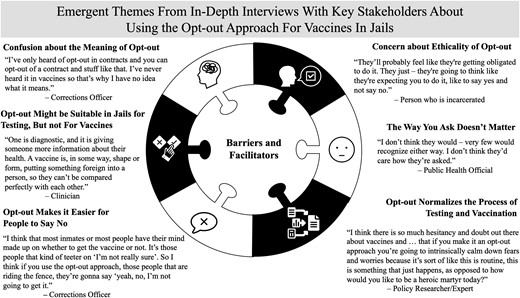

Forty-eight people were interviewed, including 13 people incarcerated at the time of interview. Themes that emerged included the following: misunderstandings of what opt-out means, indifference to the way vaccines are offered, belief that using the opt-out approach will increase the number of individuals who receive vaccination, and that opt-out provides an easy way for vaccine rejection and reluctance to accept vaccination.

There was a clear divide in stakeholders’ support of the opt-out approach, which was more universally supported by those who work outside of jails compared to those who work within or are incarcerated in jails. Compiling the perspectives of stakeholders inside and outside of jail settings on the opt-out approach to vaccination is the first step to develop feasible and effective strategies for implementing new health policies in jail settings.

The disproportionate burden of illness and death from infectious diseases experienced by criminal-legal involved populations demonstrates why carceral settings need to offer vaccines. Barriers to vaccination in carceral settings include distrust in the medical system by people who are incarcerated, cost, and staffing [1, 2]. The relatively short stay in jail in comparison to prison is also a barrier [2, 3]. Although approximately 600 000 people enter a prison in a year, there are 4.9 million individuals contributing to more than 10 million jail admissions per year [4]. The prevention and treatment of infectious diseases in jails is a key pillar in infectious disease mitigation because the majority of people incarcerated in jails return to the community where they may face barriers to access or ability to prioritize medical care and can transmit infection to others [5].

Strategies that improve access to infectious diseases testing and vaccination in the community have been implemented in carceral settings. One example of a strategy that has been used to increase infectious diseases testing is changing how it is offered from “opt-in” to “opt-out”. An example of the opt-out approach is “We draw blood for HIV testing for everyone, unless you do not want it,” which is different from the opt-in approach: “Do you want HIV testing?” As a feasible and effective strategy for increasing HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing, the opt-out approach is currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [6, 7]. The opt-out approach to HIV and HCV testing increases overall frequency of testing and decreases racial disparities in access to testing [8, 9]. Jails and prisons that have prioritized opt-out approaches have been able to improve rates of screening in their facility [10, 11]. Despite CDC recommendations for HIV and HCV opt-out testing, jails that offer testing usually use the opt-in approach, not opt-out. The reasons for the disconnect between evidence for opt-out testing and implementation are not known; however, there may be reluctance because of concerns about people who are incarcerated feeling like they do not have the ability to opt-out of something being suggested when in custody. A qualitative study from California found that some people who are incarcerated did not feel empowered to opt-out from infectious diseases testing, which raises the question of whether the opt-out approach should be used in carceral settings [12].

The opt-out approach for vaccines has been used as a strategy to increase childhood vaccine uptake [13, 14]. In addition, the opt-out approach increased coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccinations in the community [15, 16]; however, it has not been studied as a strategy to increase vaccinations in carceral settings. The COVID-19 pandemic has shined a spotlight on the health inequities experienced by people who are incarcerated and the need to partner with public health and carceral employees to develop feasible, sustainable strategies aimed at increasing vaccination in jails [17]. With the knowledge that opt-out testing strategies have been effectively implemented in jails, we gathered and analyzed perspectives from a broad group of stakeholders of applying the opt-out approach to offering vaccines in jails.

METHODS

Recruitment

This study follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) framework for qualitative research [18]. We used the “7-Ps” taxonomy to identify stakeholders, including patients, providers, payers, purchasers, policy makers, product makers, and principal investigators [19]. We recruited people who were incarcerated at Hampden County Jail in Massachusetts via convenience sampling during 2 weekly orientations. After orientation, the research team (ES, LL, and YN) described the study, and people who were interested were taken to a private room for consent and the interview. We recruited other stakeholders via snowball sampling through professional networks or referrals from participants. We conducted interviews at place of work and over Zoom. All research team members are research assistants, female, college educated, and trained in qualitative research methodology.

Patient Consent Statement

The research team conducting the interviews (ES, LL, and YN) emphasized that participation in the study was voluntary and obtained verbal consent. Tufts Health and Sciences Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Data Collection

We developed two 30-minute semistructured interview guides: one for people incarcerated in jail and another for other stakeholders. We used the theoretical domains framework to develop interview guides [20]. We piloted interview guides with stakeholders who met 7-Ps criteria for this study and iteratively refined the interview guides prior to use in the study. Those recruited for pilot interviews were not participants in the actual study. Both interview guides asked questions around perspectives and attitudes on using the opt-out approach for infectious diseases testing and vaccination in jails. We were permitted to use recording devices for interviews with participant consent. In instances in which consent was not given to record interviews, we transcribed the interview. Incarcerated people were not allowed to accept incentives. All other participants were given a $50 gift card and the opportunity to donate it to a selected local charity. People working at the jails followed institutional guidelines for accepting gifts cards. We completed interviews in English or Spanish, based on the participant's preference, between July 2021 and March 2022.

Data Analysis

We uploaded transcripts to Dedoose [21]. After developing a preliminary deductive codebook, the research team coded a subsample of interviews (ES and LL) and revised the codebook to include all emergent themes [22]. This iterative process continued until the team had produced a list of codes. We resolved discrepancies using a comparison and consensus approach. Analysis revealed that we achieved thematic saturation.

RESULTS

Ninety-five people representing stakeholder groups were approached, 35 of whom agreed to participate in the study. The breakdown of stakeholders approached and those interviewed is included in Table 1. Thirteen male participants who were incarcerated at the time of their interview were also recruited for a total of 48 participants. One topical expert lived outside of Massachusetts, but all other participants lived in Massachusetts. The demographic breakdown of our participants was 31% female, 54% non-Hispanic White, 25% Hispanic-White, and 21% non-Hispanic Black. Six key themes emerged, which we describe below and in Figure 1.

| Stakeholder Category . | Study-Specific Participant . | Number of People Approached . | Participants in Study . | %Participation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patientsa | People who are incarcerated | N/A | 13 | N/A |

| Providers | Clinicians | |||

| In jail | 11 | 8 | 72% | |

| In community | 6 | 3 | 50% | |

| Purchasers and payers | People who oversee jail operations | 28 | 14 | 50% |

| Policy makers | Public health, policy, and government employees | 38 | 6 | 16% |

| Product makers | Pharmaceutical industry representatives | 8 | 2 | 25% |

| PIs | Researchers | 4 | 2 | 50% |

| Total | … | 95 | 48 | … |

| Stakeholder Category . | Study-Specific Participant . | Number of People Approached . | Participants in Study . | %Participation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patientsa | People who are incarcerated | N/A | 13 | N/A |

| Providers | Clinicians | |||

| In jail | 11 | 8 | 72% | |

| In community | 6 | 3 | 50% | |

| Purchasers and payers | People who oversee jail operations | 28 | 14 | 50% |

| Policy makers | Public health, policy, and government employees | 38 | 6 | 16% |

| Product makers | Pharmaceutical industry representatives | 8 | 2 | 25% |

| PIs | Researchers | 4 | 2 | 50% |

| Total | … | 95 | 48 | … |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; PI, Principal Investigator.

People incarcerated in jail were approached at orientation and group meetings so we did not have a denominator.

| Stakeholder Category . | Study-Specific Participant . | Number of People Approached . | Participants in Study . | %Participation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patientsa | People who are incarcerated | N/A | 13 | N/A |

| Providers | Clinicians | |||

| In jail | 11 | 8 | 72% | |

| In community | 6 | 3 | 50% | |

| Purchasers and payers | People who oversee jail operations | 28 | 14 | 50% |

| Policy makers | Public health, policy, and government employees | 38 | 6 | 16% |

| Product makers | Pharmaceutical industry representatives | 8 | 2 | 25% |

| PIs | Researchers | 4 | 2 | 50% |

| Total | … | 95 | 48 | … |

| Stakeholder Category . | Study-Specific Participant . | Number of People Approached . | Participants in Study . | %Participation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patientsa | People who are incarcerated | N/A | 13 | N/A |

| Providers | Clinicians | |||

| In jail | 11 | 8 | 72% | |

| In community | 6 | 3 | 50% | |

| Purchasers and payers | People who oversee jail operations | 28 | 14 | 50% |

| Policy makers | Public health, policy, and government employees | 38 | 6 | 16% |

| Product makers | Pharmaceutical industry representatives | 8 | 2 | 25% |

| PIs | Researchers | 4 | 2 | 50% |

| Total | … | 95 | 48 | … |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; PI, Principal Investigator.

People incarcerated in jail were approached at orientation and group meetings so we did not have a denominator.

Confusion About the Meaning of Opt-Out

Clinicians and policy experts working outside of the jail setting had a strong grasp on the concept of the opt-out approach. When asked about their perspective, one clinician commented, “In the transplant field we’ve had a lot of debate over the years about should you have to opt-in to be an organ donor or could we presume your consent and then allow you to opt-out.” A policy expert was able to specifically apply the opt-out approach to vaccines, saying people have opted-out of vaccination for “religious purposes. You hear that a lot, that they want to be exempt.” People working or living in jails were generally less aware of the opt-out terminology being applied to medical care. One correctional officer commented, “I’ve only heard of opt-out in contracts, and you can opt-out of a contract and stuff like that. I’ve never heard it in vaccines, so that's why I have no idea what it means.” When asked to reflect on the opt-out approach for vaccines, an incarcerated person stated, “To be honest, you probably would have to read it 50 times.” Another incarcerated person had a similar opinion, saying that they, “believe it would confuse a lot of people who are not educated.” One correctional officer described opt-out approach as a “tongue twister.” A few participants who were initially confused about the utility of opt-out approach changed their minds after being told about how research supports use of the opt-out approach. One participant said, “Well, now that you’ve explained the opt-out percentages, I do [support it]”.

Opt-Out Might Be Suitable in Jails for Testing, but Not for Vaccines

Most stakeholders viewed the opt-out approach as more suitable for HIV/HCV testing than vaccines. One clinician said, “One is diagnostic, and it is giving someone more information about their health. A vaccine is, in some way, shape or form, putting something foreign into a person, so they can’t be compared perfectly with each other.” A person who was incarcerated said, “The vaccine, they shooting up they putting a chemical, an antidote in you, where testing they do it at intake and release.” A corrections officer said, “A lot of people in prison, you know, they think they’re being guinea pigs for this new vaccine. So, they don’t want something being put on them, versus testing is just testing.” A jail administrator commented on the rate of acceptance of opt-out testing and vaccination, “I would kind of think that it's higher because it's just a test and not an actual needle in your shoulder.”

In contrast, clinicians working outside of the jails and public health experts believed that testing and vaccination were similar interventions, and the opt-out approach should and could be applied to both. A physician described testing and vaccination as, “Similar goals in mind, with the idea of reduction and transmission of infectious disease.” A public health official noted, “Personally I don’t see it as different. I see it as very similar, you know? Being sort of—receiving approved health services unless you have a personal objection or reason not to be tested or vaccinated.”

Some Stakeholders Expressed Indifference About the Type of Approach Used

When asked how people in jail would feel about receiving an opt-out offer of vaccination, a public health official said, “I don’t think they would—very few would recognize either way. I don’t think they’d care how they’re asked.” A pharmaceutical representative said, “I don’t think they would notice. I think if it's seamlessly worked into their flow, I don’t even know that inmates would notice.” One correctional officer said, “if people didn’t want the vaccine, I don’t think it matters what you say to them”. One incarcerated person reflected that the way the question was asked was most important, “You were nice about it. You gave me a choice to say yes or no. You didn’t like force me or say you have to take it or you’re going to get in trouble.”

The Opt-Out Approach Raised Concerns About Ethicality

Stakeholders from all groups expressed concern about the ethics of using the opt-out approach for vaccination. One incarcerated person said, “They’ll probably feel like they’re getting obligated to do it. They just—they’re going to think like they’re expecting you to do it, like to say yes and not say no.” Another incarcerated person said, “It's like they’re telling you what they’re going to do without being straight up.” A jail administrator said “[the opt-out approach] strikes me as, I’m holding a plunger at your arm, shake your head, no, or I’m going in…you have to actively avoid the vaccine.” A public health official said, “I think they will feel like they’re not being cooperative if they opt-out, and they are being cooperative if they opt-in.” A clinician said, “It's an assumption, that they do want it if they don’t say anything. And then if there's a language barrier or if there's a cultural difference I don’t know if it gives them the ability to ask the question of, “Well, what is the vaccine?” or “How does that work?” It is almost saying, “You have to get the vaccine.” It is notable that a clinician who supported the opt-out approach believed it is up to the clinician to prevent coercion, “I think that's up to the requester to make sure that those feelings are not real, that they understand that they can say no. They’re free to refuse.”

Benefits of Opt-Out Approach for Vaccines Includes Bolstering Urgency, Trust, and Knowledge

One researcher stated, “I think there is so much hesitancy and doubt out there about vaccines and… that if you make it an opt-out approach you’re going to intrinsically calm down fears and worries because it's sort of like, ‘This is routine, this is something that just happens’, as opposed to, ‘How would you like to be a heroic martyr today’?” An industry representative said, “I think the opt-out approach communicates [sic] if you consider herd mentality, this is the norm, this is what everyone else is supposed to do.” A clinician believed that using the opt-out approach could foster trust with incarcerated patients, “With the right phrasing I think that it could normalize the process of preventative health, again, signal to individuals in correctional settings that the provider is aligned with providing them with the best care, funding with public health, aligned with the vaccines themselves, and they trust them enough to say, you know, this is just part of— this vaccine is important for this reason—you’re due for it.” A correctional officer said, “I think people will feel more at ease about it and be more apt to take the vaccine in that environment, being asked that way.”

Opt-Out Approach Can Provide an “Easy Way Out” of Vaccines

Several people, mostly people working in the jail, believed that the opt-out approach would decrease uptake of the vaccine. One corrections officer said, “They would be ecstatic because they know there's an out clause. They won’t get it.” Another corrections officer said, “I think if you use the opt-out approach, those people that are riding the fence, they’re gonna say, ‘Yeah, no, I’m not going to get it’.” A corrections officer agreed, saying, “I think the opt-out approach would lessen the number of inmates that get vaccinated just because the wording of it will give them that out clause.” Another corrections officer saw the opt-out approach as “passive” and went on to say, “You don’t even really suggest it, you know? It kind of takes away from the initial, ‘Hey, we’re offering it, but we really don’t suggest that you do it’.” A jail administrator commented on the ease of opting out saying, “Probably automatically they would just opt-out, makes it a lot faster decision.”

DISCUSSION

Our research with key stakeholders, including people who are incarcerated, reveals mixed perspectives about whether the opt-out approach should be implemented in jails to increase access to vaccines. It is notable that we found discordance between the views of academics and policy makers and people who are connected to daily jail life. Most people working in jails did not believe that the opt-out approach for vaccinations was feasible or appropriate. Several people raised concerns about coercion, a theme that also emerged in a California jail analysis [12]. With additional time and explanation, some participants were able to see the benefits of opt-out vaccination. The nuance involved with the wording of the opt-out approach, and the challenge of conveying why the method of offering testing matters, is likely a major barrier to implementation.

Although the prospect of improving access to vaccines in jails may seem daunting, infectious diseases mitigation tools have been successfully operationalized in jails when supported by research, policy, and resources. In the 1980s and 1990s, outbreaks of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) [23, 24] helped push policy makers to require strict policies for TB screening. Current jail protocols include tuberculin skin tests and chest radiographs to rule out TB. Screening all people who are incarcerated for TB during intake has successfully reduced TB infection rates in jails and prisons [25]. The cost effectiveness of screening for infectious diseases in jails and prisons has been shown for several diseases, including HIV [26], hepatitis C [9], chlamydia, and gonorrhea [27, 28]. The evidence supporting the financial and population health benefits of infectious diseases prevention in jails is clear; however, there remains a gap between recommendations to use evidence-based approaches and their actual implementation in jails.

Vaccines are the backbone of prevention and mitigation of transmission, morbidity, and mortality from influenza and COVID-19. In parallel with the opioid epidemic, there have been outbreaks of hepatitis A [29, 30] and hepatitis B [31] in people experiencing homelessness and people who inject drugs—populations who are frequently incarcerated. Vaccination for several infections, including influenza [32], hepatitis A, and hepatitis B [33], is cost effective and feasible in correctional settings. However, most research about the benefits of vaccines in jails focuses on vaccination as a mitigation strategy for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable illnesses [34–36]. There is far less attention to developing systems of increasing vaccination as general preventative tactic outside of emergency outbreak response. Although opt-out vaccination has been used in several community settings, the current guidelines from the CDC for offering vaccines in correctional settings does not include any wording about the opt-out approach.

A study looking at data from November 2017 to October 2018 found that only 10% of jails in 4 Midwest states offered the influenza vaccine [37]. Our research team conducted a content analysis of nursing intake forms from all of the 14 Massachusetts county jails and found that preventative interventions such as vaccines were infrequently offered during nursing intake, with only 2 jails of 14 offering hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination [38]. Jails located in rural areas, in particular, are at risk for barriers in vaccine delivery because they are not supported by an extensive health delivery infrastructure [39]. There has been considerable research on strategies to improve COVID-19 vaccination, including a paper by members of this research team about the experience of bringing in faith leaders, community clinicians, and medical students into the jails to answer questions about vaccines [40]. Although opt-out vaccination can be used as a strategy to improve vaccine uptake in jails, this study emphasizes that successful implementation will require work to encourage trust and ensure clear, consistent wording of the opt-out method.

The 7-P's framework provided a useful guide in identifying stakeholders who should be engaged in the discussion of how to best operationalize infectious disease prevention strategies, such as vaccination, in jails. We were able to include stakeholders who would be directly impacted by the decision to implement opt-out vaccination as well as those who are not direct decision makers but have an interest in the concept and use of the approach. Unethical research with incarcerated populations in the past necessitated heightened scrutiny for any research with criminal justice-involved populations, making several important stakeholders less inclined to engage in research, even if the research is ethical and can improve healthcare [41]. To move forward from prior unethical practices, our team was committed to engaging people who are incarcerated. Engaging people who are incarcerated in creating successful policies and programs has been seen in other areas of healthcare and can be leveraged to improve infectious disease prevention, screening, and treatment in jails [42, 43].

This research study has limitations. The voices of women experiencing incarceration are absent from this research project. Because more men are incarcerated than women, we still feel that our work represents an important addition to the literature. Second, interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when vaccination was widely discussed in media, potentially leading to responses influenced by news and public figures. Finally, social desirability bias may have impacted interviewee responses.

Stakeholders views on using the opt-out approach for vaccination in jails.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite these limitations, our research adds to the literature. The opt-out approach for infectious diseases testing may be evidence based, but several key stakeholders, including people who were incarcerated, expressed concerns about this method and its application to vaccination. As the gap between evidence and practice continues, working with the people who are living and working in the jails to better understand and address concerns about opt-out methods will be necessary.

Supplementary data

Supplementary materialsare available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Rebecca Tenner for helping to design the figure in this paper, and we acknowledge other members of the Wurcel Lab for their support throughout this project. We appreciate all those who participated in pilot interviews. Finally, we thank the staff and research administrator at Hampden County Jail for supporting our work.

Financial support. This research was supported in part by generous donations to the Tupper Research Fund at Tufts Medical Center. This work was also supported by AHRQ (Grant K08HS026008-01A; to AW), the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (Grant P30AI042853; to CGB), the COBRE on Opioids and Overdose (Grant P20GM125507; to CGB), and the Morton A. Madoff Public Health Fellowship (to LL).

References

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. CGB received grant and research support from Gilead Sciences, Inc. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Comments