-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Chloe Ah-Ryung Lim, Paris-Ann Ingledew, Analysis of the quality of meningioma education resources available on the Internet, Neuro-Oncology Practice, Volume 8, Issue 2, April 2021, Pages 129–136, https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npaa082

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Meningiomas are the most common primary central nervous system tumors and patients face difficulty evaluating resources available online. The purpose of this study is to systematically evaluate the educational resources available for patients seeking meningioma information on the Internet.

A total of 127 meningioma websites were identified by inputting the term “meningioma” on Google and two meta-search engines. A structured rating tool developed by our research group was applied to top 100 websites to evaluate with respect to accountability, interactivity, readability, and content quality. Responses to general and personal patient questions were evaluated for promptness, accuracy, and completeness. The frequency of various social media account types was analyzed.

Of 100 websites, only 38% disclosed authorship, and 32% cited sources. Sixty-two percent did not state date of creation or modification, and 32% provided last update less than 2 years ago. Websites most often discussed the definition (99%), symptoms (97%), and treatment (96%). Prevention (8%) and prognosis (47%) were most often not covered. Only 3% of websites demonstrated recommended reading level for general population. Of 84 websites contacted, 42 responded, 32 within 1 day.

Meningioma information is readily available online, but quality varies. Sites often lack markers for accountability, and content may be difficult to comprehend. Information on specific topics are often not available for patients. Physicians can direct meningioma patients to appropriate reliable online resources depicted in this study. Furthermore, future web developers can address the current gaps to design reliable online resources.

Meningiomas are generally benign tumors that originate from the meninges (or coverings) of the brain or spinal cord. According to Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States from 2005 to 2015, meningioma comprised 37.1% of primary central nervous system tumors in histological diagnosis.1 Incidence rates of meningioma significantly increase with age, with a doubled incidence after age 65 years.2 Despite most meningiomas being benign, there can be a large number of complications depending on location3 and treatment.4 They can be also associated with poor short- and long-term quality of life.5 Furthermore, histological grade impacts meningioma’s prognosis, as 5-year overall survival is 81% and 53% for atypical and malignant meningiomas, respectively.6

Patients are increasingly searching the web for medical information to inform themselves in part due to its accessibility.7 In 2015, Statistics Canada reports that 70% of Canadians use the Internet, and 58% of Canadians who use the Internet have searched for medical- or health-related information.8 In the United States, a trend analysis revealed rising Internet usage among cancer survivors from 53.5% in 2011 to 69.2% in 2017.9 Due to meningioma’s potential long-term morbidity, there is a high likelihood that the Internet is a source of information for this patient population. Quality can differ vastly among sources and patients may not have the resources to evaluate the information and to apply it to their personal circumstances.10 It is imperative for healthcare professionals to be aware of the quality of educational resources online to help patients navigate the information.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the quality of online educational resources available for meningioma patients with respect to accountability, interactivity, organization, readability, and content quality. A previous study by Saeed and Anderson assessed meningioma websites with respect to congruence with benchmarks (DISCERN score and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Clear Communication Index) to evaluate quality and used Flesch-Kincaid (FK)-grade level to evaluate readability.11 This study aims to expand on the prior study, evaluating a larger sample of top meningioma websites with additional areas relevant to site’s interactivity, organization, and accountability. Moreover, this study will investigate the utility and value of online communication accessible from contacts to social media platforms. The results of this study will provide information regarding strengths and weaknesses in the currently available online resources on meningioma, contribute to development of new online educational materials to improve patient-physician communication, and assist healthcare professionals to recommending web-based resources to patients.

Methods

Study Design

An Internet search using the term “meningioma” was performed using three different meta-search engines: Google, Yippy, and Dogpile on March 21, 2020. Yippy and Dogpile are meta-search engines combining results from several search engines, including Google, Yahoo, and Bing.12 Conducting the search in this manner results in Google being weighted more heavily reflecting its popularity.13 All searches were conducted using Chrome 80 searches were conducted in Chrome Incognito mode to prevent any personalized settings from affecting search results. The unique URLs of all websites from the search result were recorded.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the search results. Exclusion criteria were as follows: duplicated hosted links, websites requiring paid subscriptions, non-English websites, primary journal articles or for professionals, websites exclusively for fundraising or advertising purposes, blogs or discussion boards without information directed toward patients, news articles, other search engines, dictionary without relevant information for patients, and non-websites. After application of exclusion criteria, each site was assigned a value based on the average of three search engine’s order of appearance. The average of the order was listed in an ascending order, and the first 100 were considered as “top 100” websites. These top 100 websites were a representation of websites that patients are most likely to encounter on any search engine.

Subsequently, the top 100 websites were evaluated using a developed website evaluation tool.14 It was developed in 2009 and has iteratively undergone a process of validation using the principles of design-based research with application to multiple tumor sites and multiple raters to assess for the tool’s interrater reliability.15–18 This tool integrated quality criteria important to patients for website evaluation, highlighting lens of patient experience. The tool assesses each site’s accountability, interactivity, organization, readability, and content quality. Accountability was evaluated using an adaptation of the Health on the Net Foundation code,19 DISCERN criteria,20 and JAMA tool.21 The interactivity criteria were derived from Abbott’s scale.22 Site’s organizational tools were based upon Metzger’s suggested factors influencing credibility.23 Readability was evaluated by read-able.com using direct input of the introduction or treatment sections of each website. If no treatment section was present, the section on risk factors or etiology was used concomitantly with the introduction section. The FK-grade level and Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) Index were recorded.

Content quality was evaluated by the website’s coverage and accuracy. One author (C.L.) reviewed and summarized meningioma information from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and UpToDate to develop a benchmark fact sheet. The aforementioned resources are standard, peer-reviewed medical resources often used by physicians. Furthermore, these resources were used in prior studies that applied the same website evaluation tool.15–18 The sections that were deemed as necessary were: definition, incidence, etiology/risk factors, prevention, detection/workup, treatment, and prognosis. These categories are congruent with areas those cancer patients seek for information.24 Website’s coverage was evaluated based on the presence or absence of information for each category. With respect to accuracy, there were three divisions of scoring: (1) fully accurate, (2) mostly accurate or partially covered, and (3) not covered or all information is not in agreement. The fact sheet and scoring division were reviewed by the principal investigator, a practicing radiation oncologist, and a consensus document was completed after a comprehensive and iterative discussion, indicated in Table 1. A global accuracy score was based on the full agreement of all available information with the reference source. Finally, a website was given a score for objectivity if they used no persuasive language or author’s opinion and only introduced verifiable facts. The overall score was determined by adding all categories’ scores. The components of each category are depicted in Supplementary Table 1. From the overall score, top 10 websites were identified.

Information Required for a Website to be Considered to Have a “Complete” Discussion of Each Meningioma Topic

| Topic . | Required information . |

|---|---|

| Definition | Tumor that develops from meninges, AND Majority of meningioma occur within the head/brain are benign |

| Incidence or prevalence | Most common primary CNS tumor, AND Estimated 145 916 in 2011-2015 (CBTRUS), OR Equivalent numbers for the website’s country of origin, as referenced by national cancer statistics reporting agencies |

| Etiology or risk factors | Ionizing radiation, AND Genetic predisposition (such as Neurofibromatosis 2), AND Hormonal factors |

| Symptoms | Many are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, AND Seizures or other focal deficits related to the area affected |

| Prevention | Unpreventable in most cases |

| Detection or workup | Physical exam (such as neurological exam), AND MRI with contrast |

| Treatment | If small and asymptomatic, it will be observed, AND If large or symptomatic, surgical management, AND If nonresectable or poor patient condition, radiotherapy is used. |

| Prognosis | Grade 1 meningioma has excellent prognosis after surgical resection, AND Higher rates of recurrence with higher grade or non-convexity meningioma |

| Topic . | Required information . |

|---|---|

| Definition | Tumor that develops from meninges, AND Majority of meningioma occur within the head/brain are benign |

| Incidence or prevalence | Most common primary CNS tumor, AND Estimated 145 916 in 2011-2015 (CBTRUS), OR Equivalent numbers for the website’s country of origin, as referenced by national cancer statistics reporting agencies |

| Etiology or risk factors | Ionizing radiation, AND Genetic predisposition (such as Neurofibromatosis 2), AND Hormonal factors |

| Symptoms | Many are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, AND Seizures or other focal deficits related to the area affected |

| Prevention | Unpreventable in most cases |

| Detection or workup | Physical exam (such as neurological exam), AND MRI with contrast |

| Treatment | If small and asymptomatic, it will be observed, AND If large or symptomatic, surgical management, AND If nonresectable or poor patient condition, radiotherapy is used. |

| Prognosis | Grade 1 meningioma has excellent prognosis after surgical resection, AND Higher rates of recurrence with higher grade or non-convexity meningioma |

Websites that included some, but not all, required information, and/or included some factually inaccurate information were considered “mostly accurate and/or missing some required information.”

Information Required for a Website to be Considered to Have a “Complete” Discussion of Each Meningioma Topic

| Topic . | Required information . |

|---|---|

| Definition | Tumor that develops from meninges, AND Majority of meningioma occur within the head/brain are benign |

| Incidence or prevalence | Most common primary CNS tumor, AND Estimated 145 916 in 2011-2015 (CBTRUS), OR Equivalent numbers for the website’s country of origin, as referenced by national cancer statistics reporting agencies |

| Etiology or risk factors | Ionizing radiation, AND Genetic predisposition (such as Neurofibromatosis 2), AND Hormonal factors |

| Symptoms | Many are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, AND Seizures or other focal deficits related to the area affected |

| Prevention | Unpreventable in most cases |

| Detection or workup | Physical exam (such as neurological exam), AND MRI with contrast |

| Treatment | If small and asymptomatic, it will be observed, AND If large or symptomatic, surgical management, AND If nonresectable or poor patient condition, radiotherapy is used. |

| Prognosis | Grade 1 meningioma has excellent prognosis after surgical resection, AND Higher rates of recurrence with higher grade or non-convexity meningioma |

| Topic . | Required information . |

|---|---|

| Definition | Tumor that develops from meninges, AND Majority of meningioma occur within the head/brain are benign |

| Incidence or prevalence | Most common primary CNS tumor, AND Estimated 145 916 in 2011-2015 (CBTRUS), OR Equivalent numbers for the website’s country of origin, as referenced by national cancer statistics reporting agencies |

| Etiology or risk factors | Ionizing radiation, AND Genetic predisposition (such as Neurofibromatosis 2), AND Hormonal factors |

| Symptoms | Many are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, AND Seizures or other focal deficits related to the area affected |

| Prevention | Unpreventable in most cases |

| Detection or workup | Physical exam (such as neurological exam), AND MRI with contrast |

| Treatment | If small and asymptomatic, it will be observed, AND If large or symptomatic, surgical management, AND If nonresectable or poor patient condition, radiotherapy is used. |

| Prognosis | Grade 1 meningioma has excellent prognosis after surgical resection, AND Higher rates of recurrence with higher grade or non-convexity meningioma |

Websites that included some, but not all, required information, and/or included some factually inaccurate information were considered “mostly accurate and/or missing some required information.”

The initial validation of the tool showed excellent inter-rater reliability of 0.7 or higher per category.14 To ensure high inter-rater reliability, 20 randomly selected sites were independently coded by two reviewers. The kappa value and Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) were calculated to ensure a rating greater than 0.7. This was true for all categories. However, one small clarification was required for one website’s classification. This was resolved through consensus discussion to prevent subjective interpretation for the remaining 80 sites. The remaining 80 websites were coded by one reviewer.

To further evaluate interactivity, all websites with available online contact information were collected alongside the types of social media accounts obtainable. If contact information was available, they were sent three questions to determine responsiveness to patient questions. The first question pertained to a general information about meningioma: “What is the prognosis like for someone with recently diagnosed meningioma?” The second question was a personal inquiry: “I am a patient with meningioma that was not able to receive surgery because of the location. What are my next options?” The third question was regarding accessibility to any patient-friendly resources: “Are there any support groups available for patients and loved ones suffering from meningioma?” The queries were evaluated based on the number of days to respond, whether they responded to three questions, and whether the response contained referrals to various sites or healthcare practitioners. Accuracy was assessed per the consensus scoring sheet. The popularity of each type of social media accounts was analyzed, which was defined as frequency of each type.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the characteristics of the top 100 websites, popularity of social media accounts, and response from website contacts. All data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical package (version 26.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). The figures per each data were generated using GraphPad Prism version 6.0e for Mac, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com.

Results

Searching for “meningioma” generated 3 480 000 hits on Google but provided only 185 links. Yippy reported 4 490 013 hits, with 61 viable links and Dogpile did not disclose the number of websites but provided 366 viable links. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 87 websites from Google, 34 websites from Yippy, and 94 websites from Dogpile remained. After deletions of duplicated websites between search engines, there were a total of 127 unique websites compiled, available in Supplementary Table 2. The websites were given a final ranking, after an average of ascending order in each search engine. The first 100 websites were compiled and analyzed. The process of finalizing the top 100 websites is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1.

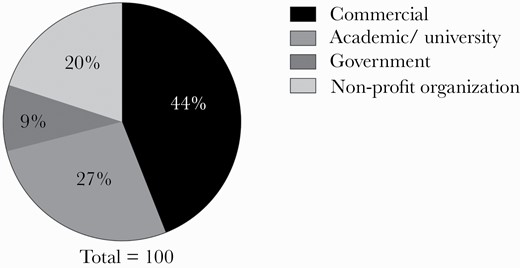

Disclosure and Classification

Websites were classified as four types of sources as shown in Figure 1: 44% (44/100) were owned by commercial, 27% (27/100) by academia or university, 20% (20/100) by non-profit organizations, and 9% (9/100) by government organizations.

Accountability

Accountability was evaluated based on authorship with affiliation or credentials, disclosure to information on site, attribution to reliable sources, the presence of external links, and the currency of the information available. Authorship was disclosed in 38% (14/38) of the websites, with 74% (28/38) authors stating their affiliation, and 79% (30/38) authors with credentials. Eighty-five percent of the sites disclosed their ownership of the site, sponsoring, or advertisement provided at the site. At least one reliable reference (eg, scientific journals, peer-reviewed sites, academic or government sites, or textbooks) was cited in 32% (32/100) of the websites, and 78% (25/32) had three or more references. External links were provided on 33% (33/100) of websites, and only 1% (32/33) of them had 50% or fewer links accessible. Finally, date of creation was identified in 23% (23/100) of websites, 38% (38/100) had a last date of modification, and 55% (55/100) had neither. Of which the date was identified, 84% of websites indicated a last update within 2 years (32/38), 8% within 2-4 years (3/38), and 8% more than 4 years prior (3/38).

Interactivity

Ninety-eight percent of sites (98/100) used at least one interactive element. Search engines were by far the most common, being present in 98% (98/100) of websites. Some websites included audio/video support relevant to the topic of “meningioma,” comprising of 19% (19/100). Other websites utilized a discussion board (15%, 15/100). Educational support such as online seminars or educational pamphlets were employed in 16% (16/100) of the websites. Finally, web-based contact information was present in 85% (85/100) of websites. Supplementary Figure 2 illustrates the responses of the 85 sites when contacted with three questions outlining general, personal, and support group inquiry. Out of the 42 sites that replied (50%, 42/85), 35 referred to a healthcare professional, 28 provided links to further information, and 15 provided links to support groups. Only 8 replied with information pertaining to the general and personal question, out of which 5 were accurate. Thirty-three websites replied within 1 day. Out of nine websites that did not reply within 1 day, three websites provided inaccurate information. Other interactive elements included usage of social media. Of all the social media platforms, Facebook was the most popular (81%, 81/100), followed by Twitter (79%, 79/100) and YouTube (66%, 66/100). Other platforms included LinkedIn, Instagram, Pinterest, Flipboard, Flickr, Snapchat, Vimeo, Tumblr, Weibo, and WhatsApp.

Organization

Organization of each site was evaluated for inclusion of the following items: headings, subheadings, hyperlinks, pictures/diagrams/tables, and the absence of advertisement. All sites contained at least one of the organizational tools. Twelve percent of websites contained all five organizational tools, 17% had four tools, 33% had three tools, 30% displayed two tools, and only 8% employed one tool.

Readability

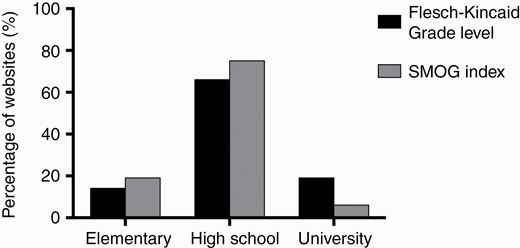

According to the FK-grade score, most websites (85%, 85/100) were at a high school level or higher. The greatest proportion of sites (66%, 66/100) was written at high school level (between grade 8 and 12), while 19% (19/100) were written in university level (above grade 13), and 14% (14/100) were written in elementary school level (less than grade 8). Similarly, SMOG Index illustrated that 19% (19/100) were written in elementary school level, 75% (75/100) in high school level, and 6% (6/100) at university level. The prevalence in various reading levels using these two assessment tools is illustrated in Figure 2.

Required reading level for comprehension of the top 100 meningioma websites. SMOG, Simple Measure of Gobbledygook.

Content quality

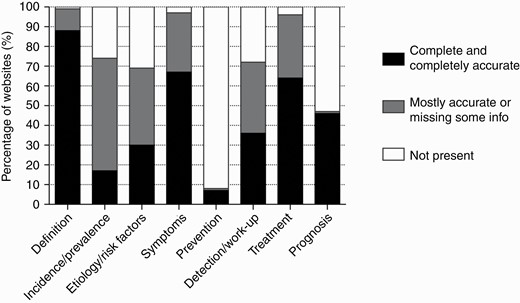

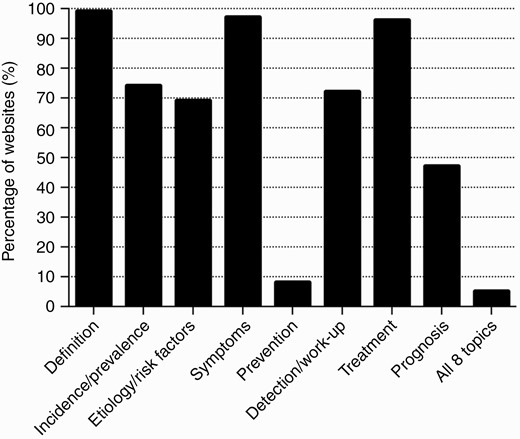

Content quality was evaluated based on both coverage and accuracy. The prevalence of content coverage with various topics in meningioma is shown in Figure 3. The topics most often covered were definition (99%, 99/100), symptoms (97%, 97/100), treatment (96%, 96/100), and incidence or prevalence (74%, 74/100). Prevention and prognosis were least often covered, on 8% (8/100) and 47% (47/100), respectively. Although incidence or prevalence and treatment were often covered, they were often the topics with most incomplete or inaccurate information (Figure 4). Only 17% (17/100) of incidence or prevalence were complete and accurate, as were 64% (64/100) for treatment. Generally, sites were far more likely to be incomplete than inaccurate.

In terms of websites’ global overall accuracy, 80% (80/100) of websites presented information that was considered entirely accurate, and 20% (20/100) of websites of mostly accurate. Nonprofit sites had the highest prevalence of accurate information at 90% (18/20) followed by government-affiliated websites (81%, 7/9), academic or university websites (78%, 21/27), and commercial websites (75%, 33/44).

The websites with highest overall scores from the standardized evaluation tool are summarized in Table 2. From the maximum score of 55, the lowest score was 15, and the highest score was 49. Thirteen websites scored 20 or less, 28 sites scored 25 or less, 51 sites scored 26 to 40, and 8 sites scored 41-55.

| Rank . | Order . | Website . | Website owner . | Score (maximum 55) . | Flesch-Kincaid grade level . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/meningioma/ | National Organization for Rare Disorders | 49 | 12.3 |

| 2 | 20 | https://mayfieldclinic.com/pe-meni.htm | Mayfield Clinic | 48 | 11 |

| 3 | 62 | https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/diseases-and-conditions/pathology/meningioma | Encyclopedia.com | 45 | 14.2 |

| 4 | 12 | https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1156552-overview | Medscape, WebMD LLC | 44 | 14.6 |

| 5-1 | 6 | https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Meningiomas | American Association of Neurological Surgeons | 43 | 11.8 |

| 5-2 | 26 | https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17858-meningioma | Cleveland Clinic | 43 | 9.3 |

| 7-1 | 1 | https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/meningioma/symptoms-causes/syc-20355643 | Mayo Clinic | 41 | 12.6 |

| 7-2 | 3 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meningioma | Wikipedia Foundation Inc. | 41 | 9.3 |

| 9 | 37 | https://patient.info/doctor/meningiomas | Patient Platform Limited | 40 | 14 |

| 10-1 | 7 | https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/meningioma | American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) | 39 | 9 |

| 10-2 | 76 | https://www.winchesterhospital.org/health-library/article?id=22830 | Winchester Hospital | 39 | 6.7 |

| Rank . | Order . | Website . | Website owner . | Score (maximum 55) . | Flesch-Kincaid grade level . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/meningioma/ | National Organization for Rare Disorders | 49 | 12.3 |

| 2 | 20 | https://mayfieldclinic.com/pe-meni.htm | Mayfield Clinic | 48 | 11 |

| 3 | 62 | https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/diseases-and-conditions/pathology/meningioma | Encyclopedia.com | 45 | 14.2 |

| 4 | 12 | https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1156552-overview | Medscape, WebMD LLC | 44 | 14.6 |

| 5-1 | 6 | https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Meningiomas | American Association of Neurological Surgeons | 43 | 11.8 |

| 5-2 | 26 | https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17858-meningioma | Cleveland Clinic | 43 | 9.3 |

| 7-1 | 1 | https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/meningioma/symptoms-causes/syc-20355643 | Mayo Clinic | 41 | 12.6 |

| 7-2 | 3 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meningioma | Wikipedia Foundation Inc. | 41 | 9.3 |

| 9 | 37 | https://patient.info/doctor/meningiomas | Patient Platform Limited | 40 | 14 |

| 10-1 | 7 | https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/meningioma | American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) | 39 | 9 |

| 10-2 | 76 | https://www.winchesterhospital.org/health-library/article?id=22830 | Winchester Hospital | 39 | 6.7 |

| Rank . | Order . | Website . | Website owner . | Score (maximum 55) . | Flesch-Kincaid grade level . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/meningioma/ | National Organization for Rare Disorders | 49 | 12.3 |

| 2 | 20 | https://mayfieldclinic.com/pe-meni.htm | Mayfield Clinic | 48 | 11 |

| 3 | 62 | https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/diseases-and-conditions/pathology/meningioma | Encyclopedia.com | 45 | 14.2 |

| 4 | 12 | https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1156552-overview | Medscape, WebMD LLC | 44 | 14.6 |

| 5-1 | 6 | https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Meningiomas | American Association of Neurological Surgeons | 43 | 11.8 |

| 5-2 | 26 | https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17858-meningioma | Cleveland Clinic | 43 | 9.3 |

| 7-1 | 1 | https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/meningioma/symptoms-causes/syc-20355643 | Mayo Clinic | 41 | 12.6 |

| 7-2 | 3 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meningioma | Wikipedia Foundation Inc. | 41 | 9.3 |

| 9 | 37 | https://patient.info/doctor/meningiomas | Patient Platform Limited | 40 | 14 |

| 10-1 | 7 | https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/meningioma | American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) | 39 | 9 |

| 10-2 | 76 | https://www.winchesterhospital.org/health-library/article?id=22830 | Winchester Hospital | 39 | 6.7 |

| Rank . | Order . | Website . | Website owner . | Score (maximum 55) . | Flesch-Kincaid grade level . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/meningioma/ | National Organization for Rare Disorders | 49 | 12.3 |

| 2 | 20 | https://mayfieldclinic.com/pe-meni.htm | Mayfield Clinic | 48 | 11 |

| 3 | 62 | https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/diseases-and-conditions/pathology/meningioma | Encyclopedia.com | 45 | 14.2 |

| 4 | 12 | https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1156552-overview | Medscape, WebMD LLC | 44 | 14.6 |

| 5-1 | 6 | https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Meningiomas | American Association of Neurological Surgeons | 43 | 11.8 |

| 5-2 | 26 | https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17858-meningioma | Cleveland Clinic | 43 | 9.3 |

| 7-1 | 1 | https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/meningioma/symptoms-causes/syc-20355643 | Mayo Clinic | 41 | 12.6 |

| 7-2 | 3 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meningioma | Wikipedia Foundation Inc. | 41 | 9.3 |

| 9 | 37 | https://patient.info/doctor/meningiomas | Patient Platform Limited | 40 | 14 |

| 10-1 | 7 | https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/meningioma | American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) | 39 | 9 |

| 10-2 | 76 | https://www.winchesterhospital.org/health-library/article?id=22830 | Winchester Hospital | 39 | 6.7 |

Discussion

The Internet is a key resource for meningioma patients; yet, studies evaluating the quality of online English meningioma websites are limited. To our knowledge, there has been only one study to date evaluating these online resources, which evaluated 29 meningioma websites on readability, quality, and communication. In this study, most sites lacked accurate and clear information.11 Our study builds on the previous study by using a structured rating tool to evaluate a larger sample size of top 100 educational online resources, evaluating other important key areas including accountability, interactivity, and organization.

Overall, the quality of meningioma websites is extremely varied and there are gaps in coverage and accuracy. Some topics are extremely well covered. In this study, treatment exhibited a high coverage frequency of 96% and a high complete accuracy of 64% websites. This is encouraging as previous studies have found that treatment is the most frequently searched topic for cancer patients.24–27 The emphasis on treatment is reassuring; yet, other key areas of information were absent. For instance, prevention was covered in only 8% of the websites. A longitudinal national survey found that misconceptions on cancer-related fatalism can be moderated with Internet search on prevention of cancer.28 Therefore, although there is no proven method to prevent meningioma, it is noteworthy for websites to comment on this to clarify misunderstandings patients or their supports may have. Additionally, accurate yet incomplete information may be misleading for the consumers. In this study, etiology/risk factors were complete and correctly depicted in 30% of websites, but 39% were mostly accurate or missing some information, and 31% did not present the information. Some websites did not highlight common risk factors such as previous radiation but mentioned others such as hormonal influences and genetic predisposition. These findings support previous work that many of the meningioma websites contain incomplete information.11

In terms of global accuracy, most websites exhibited factually correct information (80%). Non-profit organizational websites depict the highest frequency of completely accurate information. This was noted in a previous study of thyroid cancer-related websites.29

Ranking of a website on search engines such as Google or Bing does not correlate to quality.30 It may be difficult for patients to evaluate the accountability or reliability of information. This study notes less than a quarter of websites state the authorship, affiliation, or credentials. Literature supports the significance of clear authorship and disclosure for readers to determine a website’s reliability.31,32 Furthermore, citations from trustworthy sources can be a measure of reliability. In this study, 68% of sites did not cite any references to the information provided. This may lead to readers unable to verify the validity of the information presented on the site.33,34 Despite the discouraging results of identifying reliable sources and authorship, a majority of websites indicate disclosure of the information, appropriately identifying sponsor, advertisement, and inability to provide medical advice. However, most of these disclosures are often difficult to locate as they are located in the bottom of the navigation bar in a separate link.

Many websites have not recently been updated or do not provide any dates of creation. This is problematic for patients due to temporal changes in medical guidelines and evidence. Even in a scenario where meningioma practice guidelines have not changed recently an indication that the website has been reviewed can reassure patients the information remains current.

Another hurdle to navigating websites is the readability of the information. The current guidelines of National Institution of Health and American Medical Association suggest ideal health informational text to be less than sixth-grade level.35,36 However, only 3 of the 100 websites exhibited this criterion in SMOG Index. In the FK-grade level, none of the websites in the sample complied with the criterion. This closely mirrors the previously mentioned meningioma study which demonstrated that none of 29 websites were less than sixth-grade level (FK).11 This is problematic especially for lower socioeconomic status or immigrants with lower literacy levels to properly comprehend information presented in these websites,37 leading to inadequate understanding of own condition.

Organizational features can further enhance the readability of websites. For instance, pictorial representation can summarize the content and improve patient understanding and retention.38 Likewise, the presence of advertisement can lead to a negative effect in readability, whereas clear layout leads to increased readability.32 Notably, all the meningioma websites employ at least one of the organizational features. Twelve percent of the websites employ all five organizational structure, indicating an optimistic feature of meningioma websites.

When navigating the Internet, patients may find certain interactive features helpful for comprehension and positively their experience and create favorable behavioral intentions.39,40 Notably, this study demonstrated that most websites had at least one form of interactivity, the most common being search engines (98%). There is room for improvement in future websites providing more educational support.

When websites with available contacts were emailed, 50% (42/84) responded. Most websites did not provide clear answers to the general and personal questions, and 85% (35/41) referred to contact a physician. This is not surprising as there may be a reluctance for websites to respond with specific details to medical inquiries. Online communication regarding personalized medical cases can be problematic because of lacking pre-existing clinical information,41–43 which can often lead to unintentional misinformation.44 Therefore, some professional organizations provide guidelines on email use regarding clinical inquiries. For instance, the Canadian Pediatric Society advises not to provide medical advice to individuals who are not patients via email.45 Furthermore, patients are interested in support groups. With respect to the support group inquiry, 37% (15/41) responded with direct links to available support groups concerning meningioma. Nowadays, there is an increasing amount of social networking services used by cancer websites to achieve outreach.46 This study demonstrated that the top three social media services available by top 100 meningioma websites are Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Among the highest-ranking websites, the final scores ranged from 39 to 49. This range is comparable to prior studies in testicular cancer (45-49),18 thyroid cancer (42-46),15 and pancreatic cancer (47-51).16 To conclude, this study highlights that meningioma websites can improve on readability, frequent updates, and providing references. These are initial ideas that website developers can employ to improve their purpose for online education. As a correlative study to each cancer group’s website analysis, our research group survey patients on their use of Internet on particular tumor site.15,27 Meningioma patient group is yet to be explored.

There are several limitations to this study. First, only websites in English were evaluated in the study. The quality of information for non-English languages may differ, and future research is required to elucidate the quality of other language-based meningioma websites. The inclusivity of website analysis was limited by the search term “meningioma” and excluding patient forums, social media, blogs, and online groups if no informational resources were present. To mitigate the exclusion of potential support groups, websites with contact information were inquired about any support group suggestions. The support groups that were mentioned in the responses were often found to be affiliated with the respective websites. All searches were carried out from a single location and computer, which may impact the results returned by the search engines. To minimize this limitation, the author conducted the searches in Chrome’s incognito mode to deter author’s previous search history from impacting the searches. However, incognito mode cannot block the user’s IP address. Future studies can use a private browser that prevents search engines from detecting location data to provide globally generalizable results. Another limitation is that content quality was evaluated based on the aforementioned topics instead of taking into account the intention of focused coverage of specific topics. Future research can modify the current evaluation tool to consider the intended purpose of each site. Finally, 20 websites were co-coded by both authors, for inter-rater reliability. This is consistent with our prior studies, but results could be confirmed with more raters.

In conclusion, a variety of educational resources on meningioma are available on the Internet, but there is a broad range in quality. These findings provide information to help physicians to counsel patients on the strength and weaknesses of online meningioma resources. Furthermore, this study can provide suggestions in the development of new website-based educational resources to improve patient-physician communication.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine and British Columbia Cancer – Vancouver Centre.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to this work.

Code availability

All data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical package (version 26.0, SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). The figures per each data were generated using GraphPad Prism version 6.0e for Mac, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA (www.graphpad.com).

Authors’ contribution

C.A.L. and P.A.I. were responsible for the conception and design of the study. C.A.L. was responsible for searching the relevant literature, conducting the research, interpreting results, and drafting the manuscript. P.A.I. was responsible for oversight of the article and provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References