-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

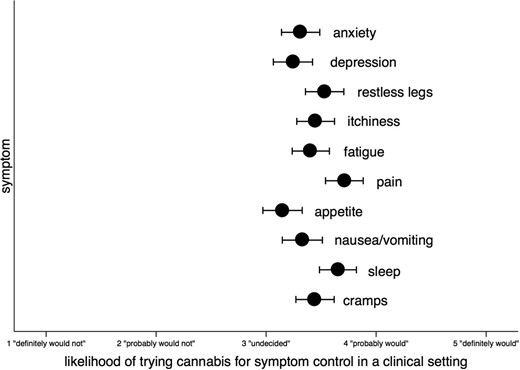

David Collister, Gwen Herrington, Lucy Delgado, Reid Whitlock, Karthik Tennankore, Navdeep Tangri, Remi Goupil, Annie-Claire Nadeau-Fredette, Sara N Davison, Ron Wald, Michael Walsh, Patient views regarding cannabis use in chronic kidney disease and kidney failure: a survey study, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 38, Issue 4, April 2023, Pages 922–931, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfac226

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Cannabis is frequently used recreationally and medicinally, including for symptom management in patients with kidney disease.

We elicited the views of Canadian adults with kidney disease regarding their cannabis use. Participants were asked whether they would try cannabis for anxiety, depression, restless legs, itchiness, fatigue, chronic pain, decreased appetite, nausea/vomiting, sleep, cramps and other symptoms. The degree to which respondents considered cannabis for each symptom was assessed with a modified Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1, definitely would not; 5, definitely would). Multilevel multivariable linear regression was used to identify respondent characteristics associated with considering cannabis for symptom control.

Of 320 respondents, 290 (90.6%) were from in-person recruitment (27.3% response rate) and 30 (9.4%) responses were from online recruitment. A total of 160/320 respondents (50.2%) had previously used cannabis, including smoking [140 (87.5%)], oils [69 (43.1%)] and edibles [92 (57.5%)]. The most common reasons for previous cannabis use were recreation [84/160 (52.5%)], pain alleviation [63/160 (39.4%)] and sleep enhancement [56/160 (35.0%)]. Only 33.8% of previous cannabis users thought their physicians were aware of their cannabis use. More than 50% of respondents probably would or definitely would try cannabis for symptom control for all 10 symptoms. Characteristics independently associated with interest in trying cannabis for symptom control included symptom type (pain, sleep, restless legs), online respondent {β = 0.7 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.1–1.4]} and previous cannabis use [β = 1.2 (95% CI 0.9–1.5)].

Many patients with kidney disease use cannabis and there is interest in trying cannabis for symptom control.

What is already known about this subject?

Cannabis is used recreationally as well as medicinally to treat chronic pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, multiple sclerosis–related spasticity and for other symptom control.

The prevalence of cannabis use, reasons for cannabis use and patient interest in participating in clinical trials of cannabis for symptom control in the setting of kidney disease is not known.

This online and in-person survey of adult patients with kidney disease from across Canada addresses these questions.

What this study adds?

More than 50% of 320 respondents had previously used cannabis and the most common type of cannabis use was smoking, oils and edibles. The most common reasons for previous cannabis use were recreation, pain alleviation and sleep enhancement.

There was interest in trying cannabis for symptom control for all types of symptoms, but pain, sleep and restless legs had the most support.

Patients have concerns regarding the efficacy, potential side effects, risk of dependency and possible impact on transplant candidacy of cannabis use.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

Randomized placebo-controlled trials that evaluate patient-reported symptom measures and adverse events are needed in patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney failure.

INTRODUCTION

Symptoms are common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and kidney failure [1] but they are often unrecognized and/or undertreated [2]. These symptoms include fatigue (71%), itchiness (55%), anorexia (49%), pain (47%), insomnia (44%), anxiety (38%), nausea (33%), restless legs syndrome (RLS) (30%) and depression (27%). Itchiness, fatigue, insomnia, depression, cramps and RLS were also 6 of the top 10 research priorities for Canadian patients with kidney failure [3]. There are few effective treatments for many of these symptoms [4–7] and residual symptoms often persist despite therapy, demonstrating the need for new treatments.

Cannabis is a promising therapy for many symptoms [8–10], as it interacts with CB1, CB2 [11] and non-cannabinoid receptors located throughout the body [12, 13]. Cannabinoids are clinically indicated to treat chronic neuropathic pain [14] and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) [15] and for appetite stimulation in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [16]. There is an urgent need to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cannabis for symptom control in patients with CKD and kidney failure.

In this study we surveyed adult Canadian patients with kidney disease regarding their views and previous experiences with cannabis, interest in using it to treat individual symptoms and barriers to its uptake in clinical and research settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey design and target audience

The survey was designed by two authors (D.C., M.W.) with input from other authors. Two patient partners (G.H., L.D.) reviewed the draft for content and clarity. The final version was pilot tested with patient partners using the survey platform surveymonkey.com (see Appendix). The survey was circulated online in July 2020 via posting on the following websites: Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD), Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research network, the Kidney Foundation of Canada (a national organization for kidney disease that promotes awareness, education, peer support and research), Canadian Nephrology Trials Network (an organization that promotes clinical trials in nephrology) and KidneyLink.ca (an online portal for kidney research opportunities in Canada). It was also posted and circulated on social media in August 2020 (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram). The target audience included English- or French-speaking adult Canadians with CKD or kidney failure [in-centre haemodialysis (ICHD), peritoneal dialysis (PD), home haemodialysis (HHD) and kidney transplantation (KT)]. Due to a poor response rate with online recruitment, we added in-person recruitment with the distribution of surveys with postage paid envelopes from January 2021 to December 2021 at the following seven sites: Seven Oaks General Hospital (Winnipeg), St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton (Hamilton), University of Alberta Hospital (Edmonton), St. Michael's Hospital (Toronto), Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre (Halifax), Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont (Montreal) and Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal (Montreal). All participants received every question but answers were not required for all questions. All responses were anonymous. Ethical approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board for the online survey (Clinical Trials Ontario Project ID 2170) and was later obtained at all other participating centres for in-person recruitment. Informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to beginning the survey.

Survey content

Demographic information

Demographic information (by self-report) included age (in 10-year increments), gender, province/territory and kidney disease and kidney replacement therapy modality (CKD, HD, PD, HHD, KT and other, which included non-CKD and non-kidney failure kidney disease such as glomerulonephritis, genetic kidney disease, stones or living kidney donors). All of this information was provided directly by participants (online and in-person) without any confirmation by a medical provider or chart review.

Previous and current cannabis use

The first section of the survey elicited previous use of cannabis, including the type (smoking, vaping, oils, pills, edibles, sprays, topicals, other) and frequency of use (every day, in the last week, in the last month, in the last year, lifetime but not in the last year, never) in addition to its prescription by a physician or healthcare provider and the indication (chronic pain, CINV, seizures/epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, appetite stimulant or other). The reasons for cannabis use not prescribed by a physician or healthcare provider were collected, including recreational use, anxiety, depression, RLS, itchiness, fatigue, pain, appetite stimulation, nausea/vomiting, sleep, cramps and other. Respondents were asked if their healthcare provider or physician was aware of their cannabis use. The type of cannabis use was also collected and categorized as mostly tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), mostly cannabidiol (CBD), similar amounts of THC/CBD, variable depending on the product, ‘I don't know’ and ‘prefer not to say’. We also asked whether a respondent's cannabis use since legalization on 17 October 2018 increased, stayed the same, decreased, was abstained from or they preferred not to say. We did not distinguish between cannabis (i.e. marijuana from the cannabis plant) and other medicinal cannabinoids such as nabilone, nabiximols and epidiolex in order to limit response burden.

Views regarding the use of cannabis in research or clinical settings for symptoms

The second section of the survey consisted of questions regarding the use of cannabis for the treatment of symptoms in the context of either a research study or for clinical use. Information was provided regarding THC and CBD and their potential effects on symptoms through action via the brain, nerves, immune system and other organs. It was also stated that research is needed to determine their efficacy and safety in CKD and kidney failure.

The first question asked participants if they would be interested in participating in a research study using prescribed cannabis as a pill or cream to reduce symptoms of kidney disease. The second question asked to what degree they would consider trying cannabis for better symptom control for each of 10 symptoms (anxiety, depression, RLS, itchiness, fatigue, pain, appetite stimulation, nausea/vomiting, sleep, cramps). Response options were categorized using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 being ‘definitely would not’, 3 being ‘undecided’ and 5 being ‘definitely would’ be in favour of trying cannabis for symptoms in a clinical setting. Participants without the individual symptom of interest had the option to choose ‘not relevant to me (I don't have this symptom)’.

Statistical analysis

All responses were used without imputing missing data. Survey respondents’ characteristics were summarized with mean [standard deviation (SD)] or median (25th–75th percentile) for continuous data and frequency (%) for categorical data. The 95% confidence intervals for proportions were calculated using the binomial exact calculation. Multilevel multivariable linear regression (individual questions regarding symptoms clustered in respondents) was performed to identify independent associations between respondent characteristics and the outcome of the likelihood of trying cannabis for symptom control in a clinical setting (on the Likert scale described above, in individuals with that symptom). The model included all potential confounding variables [17] including age, gender, province/territory, type of kidney disease, previous cannabis use and each individual symptom as fixed effects with the intercept as a random effect without any interactions [18]. P-values <.05 without adjustment for multiplicity were considered significant. We performed an a priori subgroup analysis in respondents without any previous cannabis use. All analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Respondents

Of the 1061 surveys distributed in person, there were 290 responses (90.6% of participants; response rate 27.3%) in addition to 30 online responses (9.4% of participants) (we were unable to calculate the online response rate as the number of potential respondents who opened the survey or completed it from each online source is not known), for a total of 320 responses. Respondent characteristics are shown in Table 1. Respondents were most frequently ≥60 years of age (61.2%), male (59.0%), receiving ICHD (75.8%) and had previously used cannabis [50.2% (95% CI 44.5–55.8). The majority of respondents were from Ontario (26.3%), Nova Scotia (28.4%) and Manitoba (21.6%).

| Characteristics . | n (%) . | Response rate (%) (in-person recruitment) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response type | In person | 290 (90.6) | |

| Online | 30 (9.4) | ||

| Age (years) | ≤30 | 3 (0.9) | |

| >30–40 | 12 (3.8) | ||

| >40–50 | 42 (13.2) | ||

| >50–60 | 66 (20.6) | ||

| >60–70 | 81 (25.6) | ||

| >70 | 113 (35.6) | ||

| Gender | Male | 187 (59.0) | |

| Female | 125 (39.4) | ||

| Other | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Province | Nova Scotia | 91 (28.4) | 30.0 |

| New Brunswick | 1 (0.3) | n/a | |

| Quebec | 55 (17.2) | 27.1 | |

| Ontario | 84 (26.3) | 30.0 | |

| Manitoba | 69 (21.6) | 33.0 | |

| Alberta | 14 (4.4) | 8.5 | |

| British Columbia | 6 (1.9) | n/a | |

| Kidney disease | CKD disease | 31 (9.9) | |

| In-centre HD | 238 (75.8) | ||

| PD | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Home HD | 17 (5.4) | ||

| Transplant | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Other | 6 (1.9) | ||

| Previous cannabis use | Yes | 160 (50.2) | |

| No | 158 (49.5) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Characteristics . | n (%) . | Response rate (%) (in-person recruitment) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response type | In person | 290 (90.6) | |

| Online | 30 (9.4) | ||

| Age (years) | ≤30 | 3 (0.9) | |

| >30–40 | 12 (3.8) | ||

| >40–50 | 42 (13.2) | ||

| >50–60 | 66 (20.6) | ||

| >60–70 | 81 (25.6) | ||

| >70 | 113 (35.6) | ||

| Gender | Male | 187 (59.0) | |

| Female | 125 (39.4) | ||

| Other | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Province | Nova Scotia | 91 (28.4) | 30.0 |

| New Brunswick | 1 (0.3) | n/a | |

| Quebec | 55 (17.2) | 27.1 | |

| Ontario | 84 (26.3) | 30.0 | |

| Manitoba | 69 (21.6) | 33.0 | |

| Alberta | 14 (4.4) | 8.5 | |

| British Columbia | 6 (1.9) | n/a | |

| Kidney disease | CKD disease | 31 (9.9) | |

| In-centre HD | 238 (75.8) | ||

| PD | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Home HD | 17 (5.4) | ||

| Transplant | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Other | 6 (1.9) | ||

| Previous cannabis use | Yes | 160 (50.2) | |

| No | 158 (49.5) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.3) | ||

Missing data included age (n = 3), gender (n = 3), kidney disease (n = 6) and previous cannabis use (n = 1).

n/a: not applicable.

| Characteristics . | n (%) . | Response rate (%) (in-person recruitment) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response type | In person | 290 (90.6) | |

| Online | 30 (9.4) | ||

| Age (years) | ≤30 | 3 (0.9) | |

| >30–40 | 12 (3.8) | ||

| >40–50 | 42 (13.2) | ||

| >50–60 | 66 (20.6) | ||

| >60–70 | 81 (25.6) | ||

| >70 | 113 (35.6) | ||

| Gender | Male | 187 (59.0) | |

| Female | 125 (39.4) | ||

| Other | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Province | Nova Scotia | 91 (28.4) | 30.0 |

| New Brunswick | 1 (0.3) | n/a | |

| Quebec | 55 (17.2) | 27.1 | |

| Ontario | 84 (26.3) | 30.0 | |

| Manitoba | 69 (21.6) | 33.0 | |

| Alberta | 14 (4.4) | 8.5 | |

| British Columbia | 6 (1.9) | n/a | |

| Kidney disease | CKD disease | 31 (9.9) | |

| In-centre HD | 238 (75.8) | ||

| PD | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Home HD | 17 (5.4) | ||

| Transplant | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Other | 6 (1.9) | ||

| Previous cannabis use | Yes | 160 (50.2) | |

| No | 158 (49.5) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Characteristics . | n (%) . | Response rate (%) (in-person recruitment) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response type | In person | 290 (90.6) | |

| Online | 30 (9.4) | ||

| Age (years) | ≤30 | 3 (0.9) | |

| >30–40 | 12 (3.8) | ||

| >40–50 | 42 (13.2) | ||

| >50–60 | 66 (20.6) | ||

| >60–70 | 81 (25.6) | ||

| >70 | 113 (35.6) | ||

| Gender | Male | 187 (59.0) | |

| Female | 125 (39.4) | ||

| Other | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Province | Nova Scotia | 91 (28.4) | 30.0 |

| New Brunswick | 1 (0.3) | n/a | |

| Quebec | 55 (17.2) | 27.1 | |

| Ontario | 84 (26.3) | 30.0 | |

| Manitoba | 69 (21.6) | 33.0 | |

| Alberta | 14 (4.4) | 8.5 | |

| British Columbia | 6 (1.9) | n/a | |

| Kidney disease | CKD disease | 31 (9.9) | |

| In-centre HD | 238 (75.8) | ||

| PD | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Home HD | 17 (5.4) | ||

| Transplant | 11 (3.5) | ||

| Other | 6 (1.9) | ||

| Previous cannabis use | Yes | 160 (50.2) | |

| No | 158 (49.5) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.3) | ||

Missing data included age (n = 3), gender (n = 3), kidney disease (n = 6) and previous cannabis use (n = 1).

n/a: not applicable.

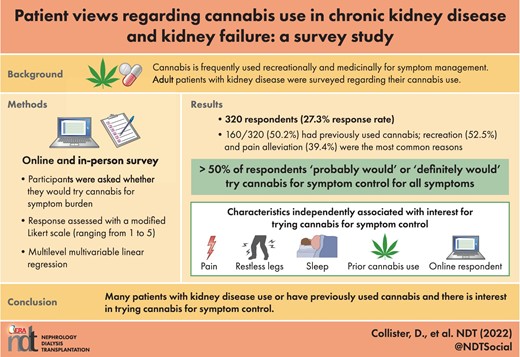

Previous experiences with cannabis use

There were 160 respondents (50.2%) who had previously used cannabis, of whom 140 (87.5%) had smoked cannabis, 69 (43.1%) had taken cannabis oil and 92 (57.5%) had taken cannabis edibles. Previous vaping, pill, spray and topical use were uncommon at 31 (19.4%), 22 (13.8%), 8 (5.0%) and 26 (16.3%) respondents, respectively. The frequency of cannabis use by route of administration is shown in Figure 1. Regarding the habitual use of cannabis (i.e. use in the last month), 32 respondents reported smoking cannabis every day, 17 in the last week and 8 in the last month (17.8% of the total cohort). Habitual use of both edibles (5 every day, 9 in the last week, 13 in the last month; 8.4% of the total cohort) and oils (4 every day, 4 in the last week and 9 in the last month; 5.3% of the total cohort) were less than habitual cannabis smoking.

Cannabis use by route in the 160 respondents with previous cannabis use.

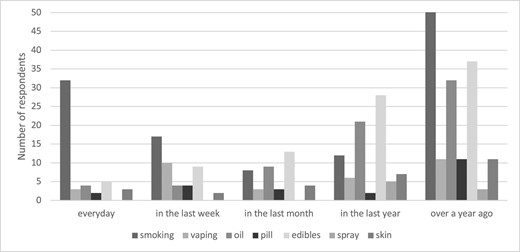

The reasons for previous cannabis use that was not prescribed by a physician or healthcare provider are shown in Figure 2. The most common reasons for previous cannabis use were recreation [84/160 (52.5%)] followed by pain alleviation [63/160 (39.4%)] and sleep enhancement [56/160 (35.0%)]. Cannabis was less commonly used for anxiety [29/160 (18.1%)], RLS [25/160 (15.6%)], depression [22/160 (13.8%)] and appetite stimulation [19/160 (11.9%)] and rarely used for nausea/vomiting [16/160 (10.0%)], fatigue [14/160 (8.8%)] or cramps [9/160 (5.6%)]. A total of 33/320 (10.3%) respondents had previously been prescribed cannabis by their physician or healthcare provider, mostly for chronic pain (n = 23), but also for appetite stimulation (n = 4), sleep (n = 3), anxiety (n = 1), depression (n = 1) and tremors (n = 1). No respondents had previously been prescribed cannabis for CINV, seizures/epilepsy or HIV/AIDS.

Reasons for non-prescription cannabis use by participants with previous cannabis use (n = 160).

Regarding the types of cannabis used, 39/144 (27.0%) did not know which type, 45/144 (31.3%) used mostly THC, 23/144 (15.9%) used mostly CBD, 17/144 (11.8%) used varying amounts of THC/CBD depending on the product and indication, 14/144 (9.7%) used similar amounts of THC/CBD and 6/144 (4.2%) preferred not to say. Of the 160 respondents with previous cannabis use, 148 responded to the question regarding physician knowledge of their cannabis use. A total of 50 (33.8%) stated that their physician was aware, 57 (38.5%) stated that their physician was not aware and 41 (27.7%) did not know. Since cannabis was legalized in Canada in October 2018, 189 respondents have not used cannabis (63.2%), 57 respondents’ cannabis use has stayed the same (19.0%), 24 has increased (8.0%), 27 has decreased (9.0%) and 2 (0.7%) preferred not to say.

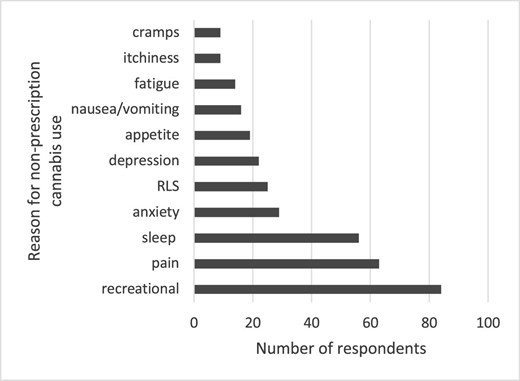

Interest in trying cannabis for symptom control

There was interest in trying cannabis for symptom control, with all symptoms having a mean score of 3 (undecided) to 4 (probably would) (Figure 3). In respondents without any previous cannabis use, there was less interest, with mean scores typically <3 (undecided) (Supplemental Table 1). The symptoms with the most interest (i.e. the percentage of respondents with the specific symptom of interest who probably would or definitely would try cannabis for symptom control in a clinical setting) included sleep [172/246 (70%), 95% CI 64–76], pain [154/219 (70%), 95% CI 64–76] and RLS [123/200 (62%), 95% CI 54–68]. but all symptoms had the support of >50% of respondents (Table 2). In respondents without any previous cannabis use, there was still interest in probably or definitely trying cannabis for symptom control in clinical settings in 25–50% of respondents across the spectrum of symptoms.

Likelihood of trying cannabis for symptom control in a clinical setting. Mean and 95% CI presented for all 10 symptoms of interest.

| . | Likert scalea . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | Not applicableb, n . | Symptom prevalence (%) . | No response, n . | Mean (SD) . | Proportion with support (95% CI)c . |

| Anxiety | 36 | 18 | 36 | 50 | 61 | 103 | 66.1 | 16 | 3.41 (1.45) | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) |

| Depression | 30 | 20 | 25 | 51 | 52 | 127 | 58.4 | 15 | 3.42 (1.44) | 0.58 (0.50–0.65) |

| Restless legs | 36 | 11 | 30 | 51 | 72 | 106 | 65.4 | 14 | 3.56 (1.47) | 0.62 (0.54–0.68) |

| Itchiness | 40 | 20 | 31 | 57 | 70 | 88 | 71.2 | 14 | 3.44 (1.48) | 0.58 (0.51–0.65) |

| Fatigue | 47 | 21 | 32 | 58 | 78 | 71 | 76.9 | 13 | 3.42 (1.51) | 0.58 (0.51–0.64) |

| Pain | 38 | 10 | 17 | 59 | 95 | 86 | 71.8 | 15 | 3.74 (1.48) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Appetite | 43 | 22 | 18 | 42 | 50 | 127 | 57.9 | 18 | 3.19 (1.57) | 0.53 (0.45–0.60) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 37 | 12 | 23 | 47 | 41 | 142 | 53.0 | 18 | 3.27 (1.50) | 0.55 (0.47–0.63) |

| Sleep | 41 | 10 | 23 | 69 | 103 | 58 | 80.9 | 16 | 3.74 (1.46) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Cramps | 41 | 9 | 31 | 68 | 53 | 97 | 67.6 | 21 | 3.41 (1.44) | 0.60 (0.53–0.67) |

| . | Likert scalea . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | Not applicableb, n . | Symptom prevalence (%) . | No response, n . | Mean (SD) . | Proportion with support (95% CI)c . |

| Anxiety | 36 | 18 | 36 | 50 | 61 | 103 | 66.1 | 16 | 3.41 (1.45) | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) |

| Depression | 30 | 20 | 25 | 51 | 52 | 127 | 58.4 | 15 | 3.42 (1.44) | 0.58 (0.50–0.65) |

| Restless legs | 36 | 11 | 30 | 51 | 72 | 106 | 65.4 | 14 | 3.56 (1.47) | 0.62 (0.54–0.68) |

| Itchiness | 40 | 20 | 31 | 57 | 70 | 88 | 71.2 | 14 | 3.44 (1.48) | 0.58 (0.51–0.65) |

| Fatigue | 47 | 21 | 32 | 58 | 78 | 71 | 76.9 | 13 | 3.42 (1.51) | 0.58 (0.51–0.64) |

| Pain | 38 | 10 | 17 | 59 | 95 | 86 | 71.8 | 15 | 3.74 (1.48) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Appetite | 43 | 22 | 18 | 42 | 50 | 127 | 57.9 | 18 | 3.19 (1.57) | 0.53 (0.45–0.60) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 37 | 12 | 23 | 47 | 41 | 142 | 53.0 | 18 | 3.27 (1.50) | 0.55 (0.47–0.63) |

| Sleep | 41 | 10 | 23 | 69 | 103 | 58 | 80.9 | 16 | 3.74 (1.46) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Cramps | 41 | 9 | 31 | 68 | 53 | 97 | 67.6 | 21 | 3.41 (1.44) | 0.60 (0.53–0.67) |

Likert scale ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 being ‘definitely would not’, 2 being ‘probably would not’, 3 being ‘undecided’, 4 being ‘probably would’ and 5 being ‘definitely would’ be in favour of trying cannabis for symptoms in a clinical setting.

Symptom is not relevant to the respondent (they do not have this symptom).

Proportion of respondents with Likert response option 4 (‘probably would’) or 5 (‘definitely would’).

| . | Likert scalea . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | Not applicableb, n . | Symptom prevalence (%) . | No response, n . | Mean (SD) . | Proportion with support (95% CI)c . |

| Anxiety | 36 | 18 | 36 | 50 | 61 | 103 | 66.1 | 16 | 3.41 (1.45) | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) |

| Depression | 30 | 20 | 25 | 51 | 52 | 127 | 58.4 | 15 | 3.42 (1.44) | 0.58 (0.50–0.65) |

| Restless legs | 36 | 11 | 30 | 51 | 72 | 106 | 65.4 | 14 | 3.56 (1.47) | 0.62 (0.54–0.68) |

| Itchiness | 40 | 20 | 31 | 57 | 70 | 88 | 71.2 | 14 | 3.44 (1.48) | 0.58 (0.51–0.65) |

| Fatigue | 47 | 21 | 32 | 58 | 78 | 71 | 76.9 | 13 | 3.42 (1.51) | 0.58 (0.51–0.64) |

| Pain | 38 | 10 | 17 | 59 | 95 | 86 | 71.8 | 15 | 3.74 (1.48) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Appetite | 43 | 22 | 18 | 42 | 50 | 127 | 57.9 | 18 | 3.19 (1.57) | 0.53 (0.45–0.60) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 37 | 12 | 23 | 47 | 41 | 142 | 53.0 | 18 | 3.27 (1.50) | 0.55 (0.47–0.63) |

| Sleep | 41 | 10 | 23 | 69 | 103 | 58 | 80.9 | 16 | 3.74 (1.46) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Cramps | 41 | 9 | 31 | 68 | 53 | 97 | 67.6 | 21 | 3.41 (1.44) | 0.60 (0.53–0.67) |

| . | Likert scalea . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | Not applicableb, n . | Symptom prevalence (%) . | No response, n . | Mean (SD) . | Proportion with support (95% CI)c . |

| Anxiety | 36 | 18 | 36 | 50 | 61 | 103 | 66.1 | 16 | 3.41 (1.45) | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) |

| Depression | 30 | 20 | 25 | 51 | 52 | 127 | 58.4 | 15 | 3.42 (1.44) | 0.58 (0.50–0.65) |

| Restless legs | 36 | 11 | 30 | 51 | 72 | 106 | 65.4 | 14 | 3.56 (1.47) | 0.62 (0.54–0.68) |

| Itchiness | 40 | 20 | 31 | 57 | 70 | 88 | 71.2 | 14 | 3.44 (1.48) | 0.58 (0.51–0.65) |

| Fatigue | 47 | 21 | 32 | 58 | 78 | 71 | 76.9 | 13 | 3.42 (1.51) | 0.58 (0.51–0.64) |

| Pain | 38 | 10 | 17 | 59 | 95 | 86 | 71.8 | 15 | 3.74 (1.48) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Appetite | 43 | 22 | 18 | 42 | 50 | 127 | 57.9 | 18 | 3.19 (1.57) | 0.53 (0.45–0.60) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 37 | 12 | 23 | 47 | 41 | 142 | 53.0 | 18 | 3.27 (1.50) | 0.55 (0.47–0.63) |

| Sleep | 41 | 10 | 23 | 69 | 103 | 58 | 80.9 | 16 | 3.74 (1.46) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Cramps | 41 | 9 | 31 | 68 | 53 | 97 | 67.6 | 21 | 3.41 (1.44) | 0.60 (0.53–0.67) |

Likert scale ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 being ‘definitely would not’, 2 being ‘probably would not’, 3 being ‘undecided’, 4 being ‘probably would’ and 5 being ‘definitely would’ be in favour of trying cannabis for symptoms in a clinical setting.

Symptom is not relevant to the respondent (they do not have this symptom).

Proportion of respondents with Likert response option 4 (‘probably would’) or 5 (‘definitely would’).

In multilevel multivariable regression models, independent predictors of willingness to try cannabis for symptom control in a clinical setting included individual symptoms [RLS 0.2 (95% CI 0.1–0.4), pain 0.4 (95% CI 0.2–0.5), appetite −0.2 (95% CI −0.3, 0) and sleep 0.3 (95% CI 0.2–0.5), all relative to anxiety], online response [0.7 (95% CI 0.1–1.4)], province [Manitoba 0.6 (95% CI 0.2–1.0), Nova Scotia 0.4 (95% CI 0.1–0.8), relative to Ontario] and previous cannabis use [1.2 (95% CI 0.9–1.5)] but not age, gender or type of kidney disease (Table 3). Results were not meaningfully different in the subgroup of previous cannabis non-users (Supplemental Table 2).

| Variables . | β . | Lower 95% CI . | Upper 95% CI . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Anxiety (reference) | ||||

| Depression | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.1 | .32 | |

| RLS | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | <.01 | |

| Itchiness | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .06 | |

| Fatigue | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .21 | |

| Pain | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Appetite | −0.2 | −0.3 | 0.0 | .03 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .86 | |

| Sleep | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Cramps | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .08 | |

| Response | Mail (reference) | ||||

| Online | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.4 | .03 | |

| Age (years) | 30–40 (reference) | ||||

| <30 | 0.1 | −1.4 | 1.5 | .94 | |

| >40–50 | 0.1 | −0.6 | 0.8 | .80 | |

| >50–60 | −0.3 | −1.0 | 0.4 | .40 | |

| >60–70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .53 | |

| >70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .63 | |

| Gender | Male (reference) | ||||

| Female | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | .54 | |

| Other | 1.1 | −0.5 | 2.8 | .18 | |

| Province | Ontario (reference) | ||||

| Alberta | 0.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | .98 | |

| British Columbia | 0.0 | −1.2 | 1.2 | 1 | |

| Manitoba | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | <.01 | |

| New Brunswick | −0.5 | −2.8 | 1.9 | .68 | |

| Nova Scotia | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | .02 | |

| Quebec | 0.2 | −0.2 | 0.7 | .32 | |

| Kidney disease | HD (reference) | ||||

| CKD | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.3 | .37 | |

| Home HD | 0.1 | −0.5 | 0.7 | .84 | |

| Kidney transplant | −0.2 | −1.2 | 0.8 | .69 | |

| PD | −0.6 | −1.4 | 0.2 | .16 | |

| Other | −0.3 | −1.3 | 0.7 | .56 | |

| Previous cannabis use | No previous cannabis use (reference) | ||||

| Prefer not to say | −0.4 | −2.6 | 1.8 | .71 | |

| Yes | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | <.01 | |

| Variables . | β . | Lower 95% CI . | Upper 95% CI . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Anxiety (reference) | ||||

| Depression | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.1 | .32 | |

| RLS | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | <.01 | |

| Itchiness | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .06 | |

| Fatigue | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .21 | |

| Pain | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Appetite | −0.2 | −0.3 | 0.0 | .03 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .86 | |

| Sleep | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Cramps | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .08 | |

| Response | Mail (reference) | ||||

| Online | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.4 | .03 | |

| Age (years) | 30–40 (reference) | ||||

| <30 | 0.1 | −1.4 | 1.5 | .94 | |

| >40–50 | 0.1 | −0.6 | 0.8 | .80 | |

| >50–60 | −0.3 | −1.0 | 0.4 | .40 | |

| >60–70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .53 | |

| >70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .63 | |

| Gender | Male (reference) | ||||

| Female | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | .54 | |

| Other | 1.1 | −0.5 | 2.8 | .18 | |

| Province | Ontario (reference) | ||||

| Alberta | 0.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | .98 | |

| British Columbia | 0.0 | −1.2 | 1.2 | 1 | |

| Manitoba | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | <.01 | |

| New Brunswick | −0.5 | −2.8 | 1.9 | .68 | |

| Nova Scotia | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | .02 | |

| Quebec | 0.2 | −0.2 | 0.7 | .32 | |

| Kidney disease | HD (reference) | ||||

| CKD | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.3 | .37 | |

| Home HD | 0.1 | −0.5 | 0.7 | .84 | |

| Kidney transplant | −0.2 | −1.2 | 0.8 | .69 | |

| PD | −0.6 | −1.4 | 0.2 | .16 | |

| Other | −0.3 | −1.3 | 0.7 | .56 | |

| Previous cannabis use | No previous cannabis use (reference) | ||||

| Prefer not to say | −0.4 | −2.6 | 1.8 | .71 | |

| Yes | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | <.01 | |

| Variables . | β . | Lower 95% CI . | Upper 95% CI . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Anxiety (reference) | ||||

| Depression | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.1 | .32 | |

| RLS | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | <.01 | |

| Itchiness | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .06 | |

| Fatigue | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .21 | |

| Pain | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Appetite | −0.2 | −0.3 | 0.0 | .03 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .86 | |

| Sleep | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Cramps | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .08 | |

| Response | Mail (reference) | ||||

| Online | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.4 | .03 | |

| Age (years) | 30–40 (reference) | ||||

| <30 | 0.1 | −1.4 | 1.5 | .94 | |

| >40–50 | 0.1 | −0.6 | 0.8 | .80 | |

| >50–60 | −0.3 | −1.0 | 0.4 | .40 | |

| >60–70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .53 | |

| >70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .63 | |

| Gender | Male (reference) | ||||

| Female | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | .54 | |

| Other | 1.1 | −0.5 | 2.8 | .18 | |

| Province | Ontario (reference) | ||||

| Alberta | 0.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | .98 | |

| British Columbia | 0.0 | −1.2 | 1.2 | 1 | |

| Manitoba | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | <.01 | |

| New Brunswick | −0.5 | −2.8 | 1.9 | .68 | |

| Nova Scotia | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | .02 | |

| Quebec | 0.2 | −0.2 | 0.7 | .32 | |

| Kidney disease | HD (reference) | ||||

| CKD | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.3 | .37 | |

| Home HD | 0.1 | −0.5 | 0.7 | .84 | |

| Kidney transplant | −0.2 | −1.2 | 0.8 | .69 | |

| PD | −0.6 | −1.4 | 0.2 | .16 | |

| Other | −0.3 | −1.3 | 0.7 | .56 | |

| Previous cannabis use | No previous cannabis use (reference) | ||||

| Prefer not to say | −0.4 | −2.6 | 1.8 | .71 | |

| Yes | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | <.01 | |

| Variables . | β . | Lower 95% CI . | Upper 95% CI . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Anxiety (reference) | ||||

| Depression | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.1 | .32 | |

| RLS | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | <.01 | |

| Itchiness | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .06 | |

| Fatigue | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .21 | |

| Pain | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Appetite | −0.2 | −0.3 | 0.0 | .03 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.2 | .86 | |

| Sleep | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | <.01 | |

| Cramps | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | .08 | |

| Response | Mail (reference) | ||||

| Online | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.4 | .03 | |

| Age (years) | 30–40 (reference) | ||||

| <30 | 0.1 | −1.4 | 1.5 | .94 | |

| >40–50 | 0.1 | −0.6 | 0.8 | .80 | |

| >50–60 | −0.3 | −1.0 | 0.4 | .40 | |

| >60–70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .53 | |

| >70 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 0.5 | .63 | |

| Gender | Male (reference) | ||||

| Female | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | .54 | |

| Other | 1.1 | −0.5 | 2.8 | .18 | |

| Province | Ontario (reference) | ||||

| Alberta | 0.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | .98 | |

| British Columbia | 0.0 | −1.2 | 1.2 | 1 | |

| Manitoba | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | <.01 | |

| New Brunswick | −0.5 | −2.8 | 1.9 | .68 | |

| Nova Scotia | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | .02 | |

| Quebec | 0.2 | −0.2 | 0.7 | .32 | |

| Kidney disease | HD (reference) | ||||

| CKD | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.3 | .37 | |

| Home HD | 0.1 | −0.5 | 0.7 | .84 | |

| Kidney transplant | −0.2 | −1.2 | 0.8 | .69 | |

| PD | −0.6 | −1.4 | 0.2 | .16 | |

| Other | −0.3 | −1.3 | 0.7 | .56 | |

| Previous cannabis use | No previous cannabis use (reference) | ||||

| Prefer not to say | −0.4 | −2.6 | 1.8 | .71 | |

| Yes | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | <.01 | |

A total of 271/303 (89.4%) respondents were interested in participating in a clinical trial of oral or topical cannabis for symptom management and of the 144 previous or current cannabis users, 115/144 (79.9%) would be willing to discontinue their current cannabis use in order to participate while 29/144 (20.1%) would not. A total of 159/311 (51.1%) respondents said they would participate in a research study of topical or oral THC/CBD for uraemic pruritus, whereas 45/311 (14.5%) did not know if they would or not. The reasons for not wanting to try cannabis for symptom control include a preference for trying other treatments (20.6%), concern that cannabis would not be effective (11.3%), concern for the risk of dependency (10.9%), concern regarding side effects (13.4%) and concern regarding transplant candidacy (9.7%). Other reasons included religion (n = 1), a view that cannabis is only a recreational drug (n = 1) and a preference for smoking rather than using oral/topical routes (n = 2).

DISCUSSION

In this survey of 320 adult patients with CKD and kidney failure from across Canada, half had previously used cannabis in their lifetime, including smoking (87.5%), edibles (57.5%) and oils (43.1%). One of ten respondents had previously been prescribed cannabis by their physician or healthcare provider, mostly for chronic pain. The most common reasons for non-prescription cannabis use were recreation (52.5%), pain (39.4%) and sleep (35.0%). Only one-third of previous cannabis users reported that their physician was aware of their cannabis use. There was interest in trying cannabis (‘undecided’ to ‘probably would’) for symptom control for anxiety, depression, RLS, itchiness, fatigue, pain, appetite stimulation, nausea/vomiting, sleep and cramps in both previous cannabis users and non-users, with potential concerns regarding efficacy, dependency, side effects and transplant candidacy.

Our results are consistent with other studies of cannabis for symptom management in CKD and kidney failure. In a recent single-centre patient survey of 192 prevalent adult patients treated with HD and PD (69.3% response rate) at the Ottawa Hospital, 14 (7.2%) and 5 (2.6%) reported previous cannabis use for their RLS and itching, respectively [19]. More than two-thirds of symptomatic patients with RLS and itching were interested in participating in future randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of cannabinoids. In our recent internet-based survey of 151 Canadian nephrologists (43.4% response rate), 19.2% had previous prescribed cannabinoids, mostly for chronic pain (79.3%) and appetite stimulation (44.8%), and 90.7% had previously cared for patients who were using non-prescription cannabinoids, mostly for recreation (88.3%), chronic pain (73.7%) and anxiety (52.6%), which is consistent with this survey [20]. There was broad support for using cannabinoids for refractory symptoms and enrolling patients in RCTs for all symptoms, and pain and sleep, as in this patient survey, were the most supported. The interest of patients and support of physicians for using cannabis for symptom control is not surprising based on a highly plausible biological rationale across symptoms [11, 21] and its potential to simultaneously target clusters of symptoms [10, 22–25].

Despite interest in the use of cannabis for symptom control from both patients and clinicians, there are a number of barriers to its use. These include but are not limited to a lack of evidence of efficacy [26–29] and safety [30, 31] in CKD and kidney failure, unfamiliarity with dosing [32, 33] and the potential for drug–drug interactions, the risk of cannabis use disorder and dependency and the potential negative impact on transplant candidacy and outcomes [34]. The finding that 17.8%, 8.4% and 5.3% of respondents are habitual users of cannabis (smoking, edibles and oils, respectively) and that only one-third of previous cannabis users had disclosed this to their physician is potentially concerning given the known harms of cannabinoids, even though they may be safe from a kidney function perspective [35, 36] as seen in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, where 83% of 3765 younger adults ages 18–30 years with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >60 ml/min/1.73 m2 reported previous or current marijuana use that was not associated with eGFR change, rapid eGFR decline or prevalent albuminuria [37]. The reasons for habitual cannabis use and poor communication between patients and their physicians in this study is not known and requires additional evaluation but may be related to recreational use, not viewing cannabis as a drug with the potential for harm, inadequate symptom management or fear of stigmatization [38].

The strengths of the study include its size, inclusion of patients across the spectrum of kidney disease from most of Canada (with both English and French speakers), its use of patient partners for survey design and piloting to enhance recruitment and its novelty and timeliness given the recent legalization of cannabis in Canada and other countries. As online recruitment using established patient organizations and research networks was suboptimal, the study transitioned to in-person recruitment. The reasons for poor online recruitment are not known but are possibly related to the demography of kidney disease in Canada (elderly and those with lower socio-economic status with limited internet access) or disinterest in research. Limitations include its response rate [perhaps due to priorities other than research given the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic], mostly in-centre HD population (presumably due to the COVID-19 pandemic and limited in-person interactions in CKD, PD, HHD and KT clinics), the lack of inclusion of patients not followed by a nephrologist, the potential for responder bias (i.e. individuals who participate in research related to cannabis are presumably more likely to be supportive of its use) and the lack of qualitative interviews to further explore patient values and preferences. In addition, the symptom prevalence in the study was higher than in previous studies, likely as a result of the study population (elderly, in-centre HD participants in a survey regarding symptom management) and the liberal ascertainment of symptoms, which could have biased our results in favour of support of novel treatments given possible selection bias. We did not collect or adjust for extensive demographic and past medical history variables including race, socio-economic status, comorbidities and mental health, which may influence cannabis use and views [39], but this was chosen in conjunction with patient partners to limit overburdening participants and maximize feasibility. Lastly, participants were not provided comprehensive information regarding the efficacy and safety of cannabinoids for individual symptoms nor did they have the opportunity to discuss treatment decisions with their nephrologist, so the degree to which responses were truly informed is unknown. However, this is the largest patient survey to date of cannabis use in CKD and kidney failure and is likely generalizable to other jurisdictions where cannabis is legalized.

In summary, approximately half of patients with CKD and kidney failure in this multicentre survey from across Canada have previously used cannabis in the form of smoking, edibles and oils, mostly for recreation, chronic pain or sleep. Patients are interested in trying cannabis for symptoms of kidney disease but have concerns regarding its efficacy, side effects, dependency and impact on their transplant candidacy. Adequately powered randomized placebo-controlled trials that evaluate patient-reported symptom measures and adverse events are needed in patients with CKD and kidney failure [40] along with single-dose and multiple-dose pharmacokinetic studies to determine appropriate dosing for oral and topical THC/CBD. Given the results of this survey and our previous survey of nephrologists, the highest priority symptoms for future trials include chronic pain, sleep, RLS and itchiness, with recruitment of both previous and new cannabis users given the potential for responder bias in any trial.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study as well as Can-SOLVE CKD, the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Nephrology Trials Network and KidneyLink.ca for circulating the survey online and via social media. D.C. is supported by a Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training Program New Investigator Award.

FUNDING

This project was supported by funding from the Michael G. DeGroote Centre for Medicinal Cannabis Research at McMaster University (https://cannabisresearch.mcmaster.ca).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it, providing intellectual content of critical importance to the work described and final approval of the version to be published.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to this work.

Comments