-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alice Doreille, Raphaël Godefroy, Jonas Martzloff, Clément Deltombe, Yosu Luque, Laurent Mesnard, Marc Hazzan, Michel Tsimaratos, Eric Rondeau, Maryvonne Hourmant, Bruno Moulin, Thomas Robert, Cédric Rafat, French nationwide survey of undocumented end-stage renal disease migrant patient access to scheduled haemodialysis and kidney transplantation, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 37, Issue 2, February 2022, Pages 393–395, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfab275

Close - Share Icon Share

Scheduled thrice-weekly haemodialysis represents the standard of care for patients suffering end-stage renal disease (ESRD) pending kidney transplantation based on cogent evidence and guidelines. Yet, when it comes to undocumented migrants with no health insurance, an emergency-only dialysis strategy is often used to treat life-threatening manifestations of ESRD [1–3]. Most available studies on dialysis in undocumented migrants stem from the USA. Nevertheless, this situation is common in Europe, where immigrants represent about 1.5% of the dialysis population [4]. The French healthcare scheme provides for full reimbursement of expenditures related to ESRD on grounds of citizenship and residence status [5, 6]. The lack of an unambiguous national policy regarding insurance coverage during the first 3 months of stay of undocumented migrants has given rise to disparate appraisal across nephrology centres in France: some centres have opted for an emergency-only dialysis strategy whereas others have settled for scheduled haemodialysis. Likewise, the decision to enrol patients on the waiting list for kidney transplantation differs according to local policy. France, akin to other European countries, has experienced a rising trend in migration, bringing these issues into the spotlight [7].

Through two nationwide surveys sponsored by the Société Francophone de Néphrologie, Dialyse et Transplantation, we sought to: (i) estimate the number of patients involved per centre, (ii) examine the determinants underpinning the decision to proceed to or forego scheduled haemodialysis and/or kidney transplantation, and (iii) investigate the clinicians’ perception of local policy. The surveys were sent through the mailing list consisting of 870 currently practicing nephrologists in France.

SURVEY 1: CLINICAL DATA AND PRACTICES

The nephrology departments of 20 hospitals (10 adult university hospitals, 6 paediatric hospitals and 4 general hospitals) responded to the survey sent in January 2020. An English version of these two surveys is available in the Supplementary data section.

The response rate was nil for both private not-for profit and for-profit facilities, 47% for public academic hospitals and 10% for public general hospitals.

A median of 4 undocumented migrants (range 0–13) were dialysed per centre over the 3 months before the survey, for a median of 65 patients (17–155) dialysed per week.

Dialysis strategy

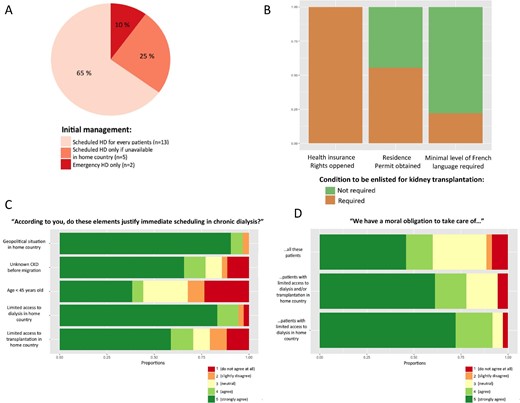

Most of the centres (n = 13, 65%) scheduled all undocumented migrants on chronic dialysis three times a week. Twenty five percent of the centres (n = 5) offered chronic dialysis only to migrants coming from countries where the access to dialysis was deemed insufficient. Two centres (10%) dialysed these patients on emergency criteria pending the grant of their health insurance rights (i.e. 3 months following arrival on French territory) (Figure 1A).

(A) Initial management of undocumented migrants with end-stage renal disease requiring chronic dialysis: 13 centres (65%) scheduled all undocumented migrants on chronic dialysis three times a week, 5 centres (25%) offered chronic dialysis only to migrants coming from countries where access to dialysis was deemed insufficient, two centres (10%) only dialysed these patients on emergency criteria until the opening of their health insurance rights (i.e. 3 months following arrival on the French territory). (B) Conditions required to be unlisted for kidney transplantation: all centres (n = 18, 100%) required health insurance rights opened. Ten centres (n = 10, 56%) also waited for residence permit. Four centres (22%) also required a minimum level of proficiency of the French language. (C) Personal opinion on elements justifying immediate scheduling in chronic dialysis (n = 36). (D) Personal opinion on nephrologists’ moral obligation (n = 36). CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Transplantation strategy

Eighteen centres offered a transplantation program. From a legal standpoint, to be enlisted for kidney transplantation, patients must have health insurance rights granted. The hospital administration policy regarding residence permit status differs between hospitals. In the majority of the centres (n = 10, 56%) enrolment on the waiting list was also contingent on holding a residence permit. Four centres (22%) additionally required a minimum level of proficiency of the French language (Figure 1B).

In 20% of the responding centres there was no consensus among clinicians regarding dialysis and transplantation listing.

SURVEY 2: CLINICIANS’ PERCEPTION

Thirty-six nephrologists answered the second survey exploring their perception of nephrological care for undocumented migrants.

The chief justifications put forward to vindicate scheduled haemodialysis were restricted access to dialysis and the geopolitical context in the country of origin (Figure 1C).

The great majority of respondents (92%) agree with the assertion according to which the management of patient with restricted access to dialysis in their home country represents a moral obligation bestowed on clinicians. Sixty percent of respondents agree with the contention stating that clinicians are morally obligated to taking care of undocumented migrants without any restrictions (Figure 1D).

For the majority of nephrologists (n = 24, 66%), undocumented migrants management causes additional stress. Thirty-nine percent (n = 14) of respondents expressed dissatisfaction with the care pertaining to dialysis in 39% (n = 14) and to kidney transplantation in 31% (n = 10).

This survey highlights the ethical conundrum related to the management of undocumented migrants with ESRD. Short of an unequivocal national policy, there is divergence in the French nephrology community on what are the meaningful grounds on which a clinician may assess the claim of an undocumented migrant to scheduled dialysis and kidney transplantation. The discrepancy in practices also highlights the complex interplay between disparate policies from one hospital administration to another and potential conflicting interpretation and application. Local hospital administrative policies may hence impact clinician's practices regardless of their core belief. The second part of the survey also revealed at least some in-medical community divergence of perception within the medical community. The survey was not devised to unravel the rationale underpinning each clinician's opinion, yet it may reflect each clinician's concern about striking a balance between ethical concerns and the fear that undocumented migrants with ESRD may represent an extra burden on an already much-strained health system. From a clinical standpoint, the consequences are subpar medical management for patients left on an emergency-based scheme and mental strain for the attending clinicians. This survey was set exclusively in France, even though the issue of dialysis and transplantation care in undocumented migrant patients is a global concern that transcends national boundaries, as reported by Van Biesen et al [4]. At any rate, it should urge for an interdisciplinary reflection and a national—or more appropriately a European—policy dedicated to channelling nephrological care to these patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are only available upon reasonable request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Comments