-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Diego Aguilar-Ramirez, Alejandro Raña-Custodio, Antonio Villa, Ximena Rubilar, Nadia Olvera, Alejandro Escobar, Richard J Johnson, Laura Sanchez-Lozada, Gregorio T Obrador, Magdalena Madero, Decreased kidney function and agricultural work: a cross-sectional study in middle-aged adults from Tierra Blanca, Mexico, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 36, Issue 6, June 2021, Pages 1030–1038, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa041

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We aimed to determine the prevalence of decreased kidney function in a potential chronic kidney disease (KD) of unknown aetiology hotspot in Mexico, assess its distribution across occupations and examine the associated risk factors.

A cross-sectional study collected sociodemographic, occupational, medical and biometric data from 616 men and women aged 20–60 years who were residents of three communities within the Tierra Blanca region in Mexico. Kidney function was assessed by standardized serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and semi-quantitative albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). To examine the distribution of decreased kidney function within the population, age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of low eGFR (≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2) was estimated for all participants and across occupations. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association of occupation with having low eGFR.

Of the 579 participants analysed (37 excluded due to missing data), the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of low eGFR was 3.5%. Agriculture was the occupation associated with the highest adjusted prevalence of low eGFR (8.8%), with 1 in every 11 agricultural workers having low eGFR. Working in agriculture was independently associated with more than a 5-fold risk of having low eGFR [odds ratio 5.2 (95% confidence interval 1.1–24.3), P = 0.032], after adjustment for age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, body mass index, ACR and family history of KD. Additionally, a quarter of the population (25%) had either low eGFR or an ACR >30 mg/g, mostly due to albuminuria.

Our work suggests that there is a high prevalence of decreased kidney function in Tierra Blanca, particularly amongst agricultural workers.

INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades, an epidemic of chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu) has emerged in several Mesoamerican countries, including El Salvador [1, 2], Costa Rica [3] and Nicaragua [4]. This epidemic, known as Mesoamerican Nephropathy (MeN), has resulted in thousands of deaths and has aroused the interest of the international community [5, 6]. The disease does not appear to follow any pattern of traditional risk factors for CKD and, as of today, the aetiology, risk factors, pathophysiological mechanisms, diagnostic methods and treatment are uncertain. A plausible hypothesis proposes that repeated episodes of acute kidney injury associated with recurrent volume depletion occurring during work shifts, amongst other yet to be elucidated factors, could explain the high burden of kidney disease (KD) in these individuals [7, 8]. The affected population typically consists of young, mostly male, agricultural workers of Hispanic ancestry exposed to long and intense working hours under extreme heat conditions in low-altitude lands [9].

The Tierra Blanca region, within the Mexican state of Veracrúz, has been identified as a potential ‘hotspot’ for CKDu by a limited number of studies that have examined this issue [10, 11], of which only one has been formally reported [12]. Tierra Blanca is a sugar cane area located in the eastern coast of Mexico, which reportedly has a high incidence of end-stage kidney disease, according to local health authorities [13]. At the National Heart Institute (INC for ‘Instituto Nacional de Cardiología’) in Mexico City, 52 patients from Tierra Blanca have been transplanted who shared similar characteristics to those described for MeN: being young male agricultural workers of which at least half had no traditional risk factors for KD, such as hypertension or diabetes [14]. However, to date, there are no studies reporting reliable estimates of the prevalence of KD in the Tierra Blanca region and the factors associated with having the disease. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of decreased kidney function [by the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)] in middle-aged population of Tierra Blanca, Veracruz, assess its distribution across occupations and examine the risk factors associated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and settings

For this cross-sectional study, we selected three rural communities in the Tierra Blanca region within the state of Veracrúz, Mexico—‘La Atalaya’, ‘Huizcolotla’ and ‘Rodríguez Tejeda’, all with <2000 inhabitants—that had been previously identified as potential CKDu hotspots by local health authorities. Furthermore, these communities were selected because agriculture, particularly sugar cane production, is the dominant economic activity with corn, cotton and beans also being cultivated for commerce. Likewise, self-employment and self-consumption or subsistence agriculture are widespread across the region. All communities have an altitude between 50 and 100 m above sea level. Tierra Blanca has a tropical monsoon climate (Am category in the Köppen climate classification) and a mean annual temperature of 31.7°C. Extreme temperatures as high as 45°C typically occur during late spring and summer.

The study was designed and conducted in coordination with state-level health authorities and took place during the first week of November 2016. Approval was obtained from the Research and Ethics Board of the State of Veracrúz Ministry of Health. After being thoroughly informed about procedures and potential benefits, all participants signed consent and received individualized feedback from local clinicians based on the tests’ results.

Participants

All adults aged 20–60 years from each community were invited to participate by local health promoters and educators. The invitations were distributed in a mixture of house-by-house delivery and by placing banners in highly visible locations (e.g. central squares, local schools or health centres) within the communities. Those interested in participating were preregistered, individually informed about the procedures and benefits of the study, and given an appointment for data collection. A non-probabilistic convenience sampling method was performed based on the availability of resources for this study. The sample was, however, weighted by population size, thus the most populated community had the largest sample size (Supplementary data, Table S1).

Procedures

All interviews and examinations were conducted in local community-based health care centres (first level of medical care). Logistics were largely based on standardized procedures from Mexico's ‘Kidney Early Evaluation Program’ (KEEP®) [15], which were adapted for this study. Briefly, sociodemographic, occupational and medical histories were obtained through a structured interview based on a standardized questionnaire. Anthropometric measurements (blood pressure, height and weight) were collected by nurses with calibrated sphygmomanometers and scales. Two nurses drew blood samples with 5-mL vacuum tubes with clot activator and gel for serum separation. Participants provided a random urine sample in a sterile 50 mL collector.

Exposures

Occupation was recorded as the main one during the last 12 months and categorised into agriculture, construction, self-employed, household worker or unemployed, or other. History of labour in sugar cane cutting, subsistence agriculture and exposure to agrochemicals was asked regardless of occupation.

Information on past or ongoing medical conditions and lifestyle behaviours included traditional risk factors for KD and cardiovascular disease. Previously diagnosed diabetes was defined as either a self-reported previous diagnosis by a health professional or current treatment with insulin or any oral anti-diabetic medication. Previously diagnosed hypertension was defined as either a self-reported previous diagnosis by a health professional or current treatment with any antihypertensive medication. Cardiovascular disease was defined as a composite of a history of coronary heart disease or stroke diagnosed by a health professional. Adiposity was measured by estimating the body mass index (BMI) in kilograms per square metre (kg/m2), which was then further categorized into the five clinically relevant groups according to World Health Organization definitions. History of KD-specific risk factors such as the family history of KD in first-grade relatives, nephrolithiasis and recurrent urinary tract infections was also collected.

Laboratory analyses

Blood samples were labelled and centrifuged on-site. Samples were refrigerated (4°C) during the day and collected for insulated transportation on ice to be processed in a central laboratory in Mexico City the following day. Every sample was analysed for serum creatinine (SCr). As recommended by clinical guidelines, SCr was measured with a standardized method traceable to isotope dilution mass spectrometry. To measure urinary albumin, we used a Clinitek Status Analyser (Siemens), a semi-quantitative point of care test device to measure albumin–creatinine ratio (ACR), which has proven to be of reliable accuracy [16]. This method classifies the ACR as <30, 30–300 and >300 mg/g.

Main outcomes

eGFR and ACR were used as indicators of kidney function. We estimated the GFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation [17]. We defined decreased kidney function as having low eGFR using the cut-off point of ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2 since it is the one associated with adverse outcomes and is considered within the conventional composite definition of CKD (either eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or ACR >30 mg/g) [18]. As an additional outcome, we estimated the prevalence of ‘probable’ (i.e. due to lack of longitudinal assessment of kidney function) CKD by using the above-mentioned composite definition of either low eGFR (≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2) or elevated ACR (>30 mg/g).

Patient consent

After being thoroughly informed about procedures and potential benefits, all participants signed consent.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups with and without low eGFR were analysed using a Chi-squared test for categorical variables and either t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables or Mann–Whitney rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Since the kidney biomarkers (i.e. creatinine and ACR) either determine or are highly correlated with having low eGFR, no hypotheses testing was performed on their distribution across eGFR groups.

To estimate the prevalence of low eGFR across the occupational groups, we used logistic regression to calculate the age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of having eGFR ≤60 mL/min/m2 within each category. To further illustrate the distribution of kidney function across groups, we additionally estimated the prevalence of eGFR ≤90 mL/min/m2 with the same procedure. These adjusted ORs were then used to back-calculate and plot adjusted percentages. The proportion of individuals with probable CKD, low eGFR and ACR ≥30 mg/g was additionally calculated within groups of interest such as age group, sex, occupation and those with traditional risk factors.

To assess the association of occupation with kidney function, we used a logistic regression model to estimate the unadjusted ORs of having low eGFR (≤60 mL/min/m2) in those working in agriculture compared with those working in any other activity. Unadjusted ORs of having low eGFR for relevant covariates were also estimated. The latter were selected a priori (age, sex, family history of KD, history of diabetes and history of hypertension) or because they were associated with low eGFR in the univariate analyses, if appropriate (BMI and ACR). Multivariable logistic regression models were then used to estimate adjusted ORs and the improvement in model fit was quantitatively compared by likelihood ratio test χ2 statistics. The adjusted ORs for all the included covariates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were plotted. A similar analysis explored the association of occupation with having an ACR >30 mg/g and with having probable CKD (Supplementary data). Analyses were performed with Stata 13.0 and plots with RStudio.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Questionnaires and samples were collected on 616 participants, of which 37 were excluded due to missing data on any of the covariates. Overall, the population was young, with a median age of 42 [interquartile range (IQR) 31–50] years, and about two-thirds were women (67.2%; Table 1). The single most frequent occupation was agriculture (21.9%). However, half of the population identified themselves as either household workers or unemployed (53.5%). Exposure to agrochemicals was reported by a quarter of the population (27.6%), about one in seven had a history of sugar cane cutting (12.8%) and one in five practiced subsistence agriculture (19.9%).

| . | Overall . | eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >60 . | ≤60 . | P-value . | ||

| . | (n = 579) . | (n = 560) . | (n = 19) . | . |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 42.0 (31.0–50.0) | 41.0 (31.0–50.0) | 47.0 (33.0–53.0) | 0.14 |

| Men | 190 (32.8) | 182 (32.5) | 8 (42.1) | 0.38 |

| Women | 389 (67.2) | 378 (67.5) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Education | ||||

| College or university | 71 (12.3) | 70 (12.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0.20 |

| High school | 279 (48.2) | 272 (48.6) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Elementary | 208 (35.9) | 197 (35.2) | 11 (57.9) | |

| No formal education | 21 (3.6) | 21 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Residence | ||||

| Rodriguez Tejeda | 281 (48.5) | 271 (48.4) | 10 (52.6) | 0.23 |

| Huixcolotla | 182 (31.4) | 174 (31.1) | 8 (42.1) | |

| La Atalaya | 116 (20.0) | 115 (20.5) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Occupational characteristics | ||||

| Self-reported work in the last 12 months | ||||

| Agriculture | 127 (21.9) | 119 (21.3) | 8 (42.1) | 0.031 |

| Self-employed/merchant | 40 (6.9) | 40 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.23 |

| Construction | 21 (3.6) | 20 (3.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0.70 |

| Household worker/unemployed | 310 (53.5) | 301 (53.8) | 9 (47.4) | 0.58 |

| Other | 81 (14.0) | 80 (14.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.26 |

| Agriculture-specific activities | ||||

| History of sugar cane cutting | 74 (12.8) | 72 (12.9) | 2 (10.5) | 0.76 |

| Subsistence agriculture | 115 (19.9) | 109 (19.5) | 6 (31.6) | 0.19 |

| Exposure to agrochemicals | 160 (27.6) | 150 (26.8) | 10 (52.6) | 0.013 |

| Disease history | ||||

| Previously diagnosed diabetes | 79 (13.6) | 72 (12.9) | 7 (36.8) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 (2.2) | 12 (2.1) | 1 (5.3) | 0.37 |

| Previously diagnosed hypertension | 74 (12.8) | 68 (12.1) | 6 (31.6) | 0.013 |

| Kidney-specific risk factors | ||||

| Family history of KD | 104 (18.0) | 99 (17.7) | 5 (26.3) | 0.33 |

| History of nephrolithiasis | 53 (9.2) | 52 (9.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.55 |

| Recurrent urinary tract infections | 228 (39.4) | 219 (39.1) | 9 (47.4) | 0.47 |

| Any probable cause of KDb | 164 (28.3) | 154 (27.5) | 10 (52.6) | 0.017 |

| Anthropometric measurements | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 29.4 (5.5) | 29.5 (5.4) | 27.4 (6.0) | 0.098 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 8 (1.4) | 6 (1.1) | 2 (10.5) | 0.003 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 107 (18.5) | 104 (18.6) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 211 (36.4) | 201 (35.9) | 10 (52.6) | |

| Obesity I (30–39.9) | 228 (39.4) | 225 (40.2) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Obesity II (≥40) | 25 (4.3) | 24 (4.3) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic, mean (SD) | 113.7 (16.7) | 113.4 (16.4) | 124.5 (21.3) | 0.004 |

| Diastolic, mean (SD) | 74.8 (10.7) | 74.6 (10.6) | 78.9 (11.4) | 0.082 |

| Kidney biomarkers | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.2) | 2.2 (1.8) | NE |

| Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | NE |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 108.2 (19.2) | 110.5 (14.7) | 41.1 (16.4) | NE |

| ≤90 | 77 (13.3) | 58 (10.4) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ≤60 | 19 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ACR (mg/g) | ||||

| <30 | 442 (76.3) | 436 (77.9) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| 30–300 | 124 (21.4) | 117 (20.9) | 7 (36.8) | NE |

| >300 | 13 (2.2) | 7 (1.3) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| Probable CKD | 143 (24.7) | 124 (22.1) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| . | Overall . | eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >60 . | ≤60 . | P-value . | ||

| . | (n = 579) . | (n = 560) . | (n = 19) . | . |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 42.0 (31.0–50.0) | 41.0 (31.0–50.0) | 47.0 (33.0–53.0) | 0.14 |

| Men | 190 (32.8) | 182 (32.5) | 8 (42.1) | 0.38 |

| Women | 389 (67.2) | 378 (67.5) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Education | ||||

| College or university | 71 (12.3) | 70 (12.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0.20 |

| High school | 279 (48.2) | 272 (48.6) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Elementary | 208 (35.9) | 197 (35.2) | 11 (57.9) | |

| No formal education | 21 (3.6) | 21 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Residence | ||||

| Rodriguez Tejeda | 281 (48.5) | 271 (48.4) | 10 (52.6) | 0.23 |

| Huixcolotla | 182 (31.4) | 174 (31.1) | 8 (42.1) | |

| La Atalaya | 116 (20.0) | 115 (20.5) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Occupational characteristics | ||||

| Self-reported work in the last 12 months | ||||

| Agriculture | 127 (21.9) | 119 (21.3) | 8 (42.1) | 0.031 |

| Self-employed/merchant | 40 (6.9) | 40 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.23 |

| Construction | 21 (3.6) | 20 (3.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0.70 |

| Household worker/unemployed | 310 (53.5) | 301 (53.8) | 9 (47.4) | 0.58 |

| Other | 81 (14.0) | 80 (14.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.26 |

| Agriculture-specific activities | ||||

| History of sugar cane cutting | 74 (12.8) | 72 (12.9) | 2 (10.5) | 0.76 |

| Subsistence agriculture | 115 (19.9) | 109 (19.5) | 6 (31.6) | 0.19 |

| Exposure to agrochemicals | 160 (27.6) | 150 (26.8) | 10 (52.6) | 0.013 |

| Disease history | ||||

| Previously diagnosed diabetes | 79 (13.6) | 72 (12.9) | 7 (36.8) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 (2.2) | 12 (2.1) | 1 (5.3) | 0.37 |

| Previously diagnosed hypertension | 74 (12.8) | 68 (12.1) | 6 (31.6) | 0.013 |

| Kidney-specific risk factors | ||||

| Family history of KD | 104 (18.0) | 99 (17.7) | 5 (26.3) | 0.33 |

| History of nephrolithiasis | 53 (9.2) | 52 (9.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.55 |

| Recurrent urinary tract infections | 228 (39.4) | 219 (39.1) | 9 (47.4) | 0.47 |

| Any probable cause of KDb | 164 (28.3) | 154 (27.5) | 10 (52.6) | 0.017 |

| Anthropometric measurements | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 29.4 (5.5) | 29.5 (5.4) | 27.4 (6.0) | 0.098 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 8 (1.4) | 6 (1.1) | 2 (10.5) | 0.003 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 107 (18.5) | 104 (18.6) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 211 (36.4) | 201 (35.9) | 10 (52.6) | |

| Obesity I (30–39.9) | 228 (39.4) | 225 (40.2) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Obesity II (≥40) | 25 (4.3) | 24 (4.3) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic, mean (SD) | 113.7 (16.7) | 113.4 (16.4) | 124.5 (21.3) | 0.004 |

| Diastolic, mean (SD) | 74.8 (10.7) | 74.6 (10.6) | 78.9 (11.4) | 0.082 |

| Kidney biomarkers | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.2) | 2.2 (1.8) | NE |

| Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | NE |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 108.2 (19.2) | 110.5 (14.7) | 41.1 (16.4) | NE |

| ≤90 | 77 (13.3) | 58 (10.4) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ≤60 | 19 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ACR (mg/g) | ||||

| <30 | 442 (76.3) | 436 (77.9) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| 30–300 | 124 (21.4) | 117 (20.9) | 7 (36.8) | NE |

| >300 | 13 (2.2) | 7 (1.3) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| Probable CKD | 143 (24.7) | 124 (22.1) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

Values are represented as n (%) unless otherwise mentioned.

eGFR was derived using the CKD-EPI formula based on SCr measured IDMS tractable standards. The 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 cut-off was selected due to its clinical relevance.

Any probable cause of kidney disease was defined as any of the following: previously diagnosed diabetes, previously diagnosed hypertension or self-reported history of nephrolithiasis.

NE, not estimated; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; IDMS, isotope dilution mass spectrometry.

| . | Overall . | eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >60 . | ≤60 . | P-value . | ||

| . | (n = 579) . | (n = 560) . | (n = 19) . | . |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 42.0 (31.0–50.0) | 41.0 (31.0–50.0) | 47.0 (33.0–53.0) | 0.14 |

| Men | 190 (32.8) | 182 (32.5) | 8 (42.1) | 0.38 |

| Women | 389 (67.2) | 378 (67.5) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Education | ||||

| College or university | 71 (12.3) | 70 (12.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0.20 |

| High school | 279 (48.2) | 272 (48.6) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Elementary | 208 (35.9) | 197 (35.2) | 11 (57.9) | |

| No formal education | 21 (3.6) | 21 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Residence | ||||

| Rodriguez Tejeda | 281 (48.5) | 271 (48.4) | 10 (52.6) | 0.23 |

| Huixcolotla | 182 (31.4) | 174 (31.1) | 8 (42.1) | |

| La Atalaya | 116 (20.0) | 115 (20.5) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Occupational characteristics | ||||

| Self-reported work in the last 12 months | ||||

| Agriculture | 127 (21.9) | 119 (21.3) | 8 (42.1) | 0.031 |

| Self-employed/merchant | 40 (6.9) | 40 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.23 |

| Construction | 21 (3.6) | 20 (3.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0.70 |

| Household worker/unemployed | 310 (53.5) | 301 (53.8) | 9 (47.4) | 0.58 |

| Other | 81 (14.0) | 80 (14.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.26 |

| Agriculture-specific activities | ||||

| History of sugar cane cutting | 74 (12.8) | 72 (12.9) | 2 (10.5) | 0.76 |

| Subsistence agriculture | 115 (19.9) | 109 (19.5) | 6 (31.6) | 0.19 |

| Exposure to agrochemicals | 160 (27.6) | 150 (26.8) | 10 (52.6) | 0.013 |

| Disease history | ||||

| Previously diagnosed diabetes | 79 (13.6) | 72 (12.9) | 7 (36.8) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 (2.2) | 12 (2.1) | 1 (5.3) | 0.37 |

| Previously diagnosed hypertension | 74 (12.8) | 68 (12.1) | 6 (31.6) | 0.013 |

| Kidney-specific risk factors | ||||

| Family history of KD | 104 (18.0) | 99 (17.7) | 5 (26.3) | 0.33 |

| History of nephrolithiasis | 53 (9.2) | 52 (9.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.55 |

| Recurrent urinary tract infections | 228 (39.4) | 219 (39.1) | 9 (47.4) | 0.47 |

| Any probable cause of KDb | 164 (28.3) | 154 (27.5) | 10 (52.6) | 0.017 |

| Anthropometric measurements | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 29.4 (5.5) | 29.5 (5.4) | 27.4 (6.0) | 0.098 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 8 (1.4) | 6 (1.1) | 2 (10.5) | 0.003 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 107 (18.5) | 104 (18.6) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 211 (36.4) | 201 (35.9) | 10 (52.6) | |

| Obesity I (30–39.9) | 228 (39.4) | 225 (40.2) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Obesity II (≥40) | 25 (4.3) | 24 (4.3) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic, mean (SD) | 113.7 (16.7) | 113.4 (16.4) | 124.5 (21.3) | 0.004 |

| Diastolic, mean (SD) | 74.8 (10.7) | 74.6 (10.6) | 78.9 (11.4) | 0.082 |

| Kidney biomarkers | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.2) | 2.2 (1.8) | NE |

| Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | NE |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 108.2 (19.2) | 110.5 (14.7) | 41.1 (16.4) | NE |

| ≤90 | 77 (13.3) | 58 (10.4) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ≤60 | 19 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ACR (mg/g) | ||||

| <30 | 442 (76.3) | 436 (77.9) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| 30–300 | 124 (21.4) | 117 (20.9) | 7 (36.8) | NE |

| >300 | 13 (2.2) | 7 (1.3) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| Probable CKD | 143 (24.7) | 124 (22.1) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| . | Overall . | eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >60 . | ≤60 . | P-value . | ||

| . | (n = 579) . | (n = 560) . | (n = 19) . | . |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 42.0 (31.0–50.0) | 41.0 (31.0–50.0) | 47.0 (33.0–53.0) | 0.14 |

| Men | 190 (32.8) | 182 (32.5) | 8 (42.1) | 0.38 |

| Women | 389 (67.2) | 378 (67.5) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Education | ||||

| College or university | 71 (12.3) | 70 (12.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0.20 |

| High school | 279 (48.2) | 272 (48.6) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Elementary | 208 (35.9) | 197 (35.2) | 11 (57.9) | |

| No formal education | 21 (3.6) | 21 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Residence | ||||

| Rodriguez Tejeda | 281 (48.5) | 271 (48.4) | 10 (52.6) | 0.23 |

| Huixcolotla | 182 (31.4) | 174 (31.1) | 8 (42.1) | |

| La Atalaya | 116 (20.0) | 115 (20.5) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Occupational characteristics | ||||

| Self-reported work in the last 12 months | ||||

| Agriculture | 127 (21.9) | 119 (21.3) | 8 (42.1) | 0.031 |

| Self-employed/merchant | 40 (6.9) | 40 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.23 |

| Construction | 21 (3.6) | 20 (3.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0.70 |

| Household worker/unemployed | 310 (53.5) | 301 (53.8) | 9 (47.4) | 0.58 |

| Other | 81 (14.0) | 80 (14.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.26 |

| Agriculture-specific activities | ||||

| History of sugar cane cutting | 74 (12.8) | 72 (12.9) | 2 (10.5) | 0.76 |

| Subsistence agriculture | 115 (19.9) | 109 (19.5) | 6 (31.6) | 0.19 |

| Exposure to agrochemicals | 160 (27.6) | 150 (26.8) | 10 (52.6) | 0.013 |

| Disease history | ||||

| Previously diagnosed diabetes | 79 (13.6) | 72 (12.9) | 7 (36.8) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 (2.2) | 12 (2.1) | 1 (5.3) | 0.37 |

| Previously diagnosed hypertension | 74 (12.8) | 68 (12.1) | 6 (31.6) | 0.013 |

| Kidney-specific risk factors | ||||

| Family history of KD | 104 (18.0) | 99 (17.7) | 5 (26.3) | 0.33 |

| History of nephrolithiasis | 53 (9.2) | 52 (9.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0.55 |

| Recurrent urinary tract infections | 228 (39.4) | 219 (39.1) | 9 (47.4) | 0.47 |

| Any probable cause of KDb | 164 (28.3) | 154 (27.5) | 10 (52.6) | 0.017 |

| Anthropometric measurements | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 29.4 (5.5) | 29.5 (5.4) | 27.4 (6.0) | 0.098 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 8 (1.4) | 6 (1.1) | 2 (10.5) | 0.003 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 107 (18.5) | 104 (18.6) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 211 (36.4) | 201 (35.9) | 10 (52.6) | |

| Obesity I (30–39.9) | 228 (39.4) | 225 (40.2) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Obesity II (≥40) | 25 (4.3) | 24 (4.3) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic, mean (SD) | 113.7 (16.7) | 113.4 (16.4) | 124.5 (21.3) | 0.004 |

| Diastolic, mean (SD) | 74.8 (10.7) | 74.6 (10.6) | 78.9 (11.4) | 0.082 |

| Kidney biomarkers | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.2) | 2.2 (1.8) | NE |

| Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | NE |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 108.2 (19.2) | 110.5 (14.7) | 41.1 (16.4) | NE |

| ≤90 | 77 (13.3) | 58 (10.4) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ≤60 | 19 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

| ACR (mg/g) | ||||

| <30 | 442 (76.3) | 436 (77.9) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| 30–300 | 124 (21.4) | 117 (20.9) | 7 (36.8) | NE |

| >300 | 13 (2.2) | 7 (1.3) | 6 (31.6) | NE |

| Probable CKD | 143 (24.7) | 124 (22.1) | 19 (100.0) | NE |

Values are represented as n (%) unless otherwise mentioned.

eGFR was derived using the CKD-EPI formula based on SCr measured IDMS tractable standards. The 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 cut-off was selected due to its clinical relevance.

Any probable cause of kidney disease was defined as any of the following: previously diagnosed diabetes, previously diagnosed hypertension or self-reported history of nephrolithiasis.

NE, not estimated; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; IDMS, isotope dilution mass spectrometry.

Previously diagnosed diabetes and hypertension were reported by 13.6% and 12.8% of the participants, respectively, whereas the family history of KD was reported by almost a fifth (18%) of the population. The mean BMI was 29.4 kg/m2, with a third (36.4%) and almost half (43.7%) the population being overweight and obese, respectively.

The median SCr of the population was 0.7 mg/dL (IQR 0.6–0.8) with a mean eGFR of 108.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 (SD 19.2). Furthermore, 13.3% and 3.3% of the participants had an eGFR ≤90 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. The ACR was elevated in almost a quarter of the population (23.7%), with 2.2% having >300 mg/g. The overall prevalence of probable CKD (i.e. either eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or ACR >30 mg/g) was 24.7% and was largely due to elevated ACR (124 of 143 classified as with probable CKD were due to an ACR >30 mg/g; Supplementary data, Table S1 and S2).

Comparison of participants with and without low eGFR (≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2)

As presented in Table 1, when compared with those with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2, participants with low eGFR were moderately, albeit not significantly, older (median 47 versus 41 years, P = 0.14). There were no significant differences by sex, education and residence. When considering occupation, working in agriculture was more frequently reported amongst those with low eGFR (42% versus 21%, P = 0.031) when compared with those with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Similarly, participants with low eGFR more often reported having been exposed to agrochemicals (55% versus 27%, P = 0.013). There were no significant differences in the report of the history of sugar cane cutting (12.9% versus 10.5%, P = 0.76) or practicing subsistence agriculture (32% versus 20%, P = 0.19) across eGFR groups.

Previously diagnosed diabetes and previously diagnosed hypertension were significantly more frequent amongst those with low eGFR (37% versus 13%, P = 0.003 and 32% versus 12%, P = 0.013, respectively). A quarter and almost half of those with low eGFR had a family history of KD and recurrent urinary tract infections, but they were not significantly different from the group with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Furthermore, adiposity appeared to be lower in those with low eGFR with a lower mean BMI (27.4 versus 29.5, P = 0.098) and a lower proportion of obesity (21.1% versus 44.5%, P = 0.003). Likewise, both systolic and diastolic blood pressure were higher in the low eGFR group.

The median SCr of those with low eGFR was 1.7 mg/dL (IQR 1.2–2.6) with a mean eGFR of 41.1 (SD 16.4) mL/min/1.73 m2. The ACR was elevated in two-thirds of the participants with low eGFR, of which a third had ACR between 30 and 300 mg/g and a third >300 mg/g. A third of those with low eGFR, however, had an ACR measurement <30 mg/g.

Prevalence of low eGFR by occupation

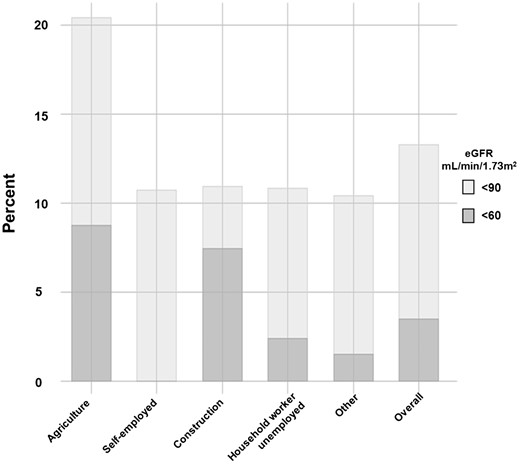

Figure 1 shows the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of low eGFR at cut-off points of ≤60 and ≤90 mL/min/1.73 m2 stratified by self-reported occupation categories and in the total population. Those working in agriculture had an 8.8% adjusted prevalence of eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2, which was substantially higher than the overall prevalence of 3.5% and substantially higher than any other occupation category except for construction workers (7.5%). The prevalence of eGFR ≤90 mL/min/1.73 m2 was also substantially increased amongst agricultural workers, with an adjusted prevalence of 20.4%, when compared with the overall prevalence of 13.3%.

Age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of eGFR <90 and <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, by occupation. The figure shows the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of decreased estimated eGFR at specific cut-off points stratified by varied self-reported occupation categories. The overall category shows the estimated prevalence in the population, irrespective of occupation. The corresponding point estimates for eGFR <90 and <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 are, respectively, 20.4% and 8.8% for agriculture, 10.8% and 0.0% for self-employed, 10.9% and 7.5% for construction, 10.9% and 2.4% for homemaker and 10.4% and 1.6% for other. The overall estimates are 13.3% and 3.5%. The eGFR was estimated using Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula and derived from SCr.

Association between working in agriculture and having low eGFR (≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2)

As shown in Table 2 and Supplementary data, Table S3, the unadjusted logistic regression model showed that those working in agriculture had more than double the odds [OR 2.67 (95% CI 1.06–6.85)] of having low eGFR, when compared with those with any other occupation. Further sequential adjustment for age and sex, diabetes and hypertension, BMI, family history of KD and ACR >30 mg/g showed an increase in the strength of the association between working in agriculture and the odds of having low eGFR, with an OR for having low eGFR of 5.19 (95% CI 1.11–24.26, fully adjusted model) for those working in agriculture.

ORs for having eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for those working in agriculture and effect of adjustment

| Covariate . | OR (95% CI) . | χ2 (df) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture . | Model . | P-valuea . | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.695 (1.060–6.851) | 4.01 (1) | 4.01 (1) | NA |

| +Age, sex | 3.816 (0.892–16.313) | 3.39 (1) | 6.26 (3) | 0.066 |

| +Diabetes, hypertension | 4.750 (1.118–20.173) | 4.67 (1) | 14.74 (5) | 0.031 |

| +BMI | 4.150 (1.034–16.658) | 4.16 (1) | 19.85 (6) | 0.041 |

| +Family history of KD | 4.378 (1.053–18.197) | 4.31 (1) | 20.51 (7) | 0.038 |

| +ACR >30 mg/g | 5.191 (1.111–24.258) | 4.59 (1) | 32.03 (8) | 0.032 |

| Covariate . | OR (95% CI) . | χ2 (df) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture . | Model . | P-valuea . | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.695 (1.060–6.851) | 4.01 (1) | 4.01 (1) | NA |

| +Age, sex | 3.816 (0.892–16.313) | 3.39 (1) | 6.26 (3) | 0.066 |

| +Diabetes, hypertension | 4.750 (1.118–20.173) | 4.67 (1) | 14.74 (5) | 0.031 |

| +BMI | 4.150 (1.034–16.658) | 4.16 (1) | 19.85 (6) | 0.041 |

| +Family history of KD | 4.378 (1.053–18.197) | 4.31 (1) | 20.51 (7) | 0.038 |

| +ACR >30 mg/g | 5.191 (1.111–24.258) | 4.59 (1) | 32.03 (8) | 0.032 |

Any other self-reported occupation was used as reference group. Age was modelled as a continuous variable. Diabetes and hypertension were defined as a previous medical diagnosis. BMI was modelled as a continuous variable.

Reported P-values correspond to the likelihood ratio test comparing the model with and without agriculture as a covariate, thus effectively assessing the goodness of fit of the tested covariate (i.e. agriculture) for the logistic regression model.

ORs for having eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for those working in agriculture and effect of adjustment

| Covariate . | OR (95% CI) . | χ2 (df) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture . | Model . | P-valuea . | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.695 (1.060–6.851) | 4.01 (1) | 4.01 (1) | NA |

| +Age, sex | 3.816 (0.892–16.313) | 3.39 (1) | 6.26 (3) | 0.066 |

| +Diabetes, hypertension | 4.750 (1.118–20.173) | 4.67 (1) | 14.74 (5) | 0.031 |

| +BMI | 4.150 (1.034–16.658) | 4.16 (1) | 19.85 (6) | 0.041 |

| +Family history of KD | 4.378 (1.053–18.197) | 4.31 (1) | 20.51 (7) | 0.038 |

| +ACR >30 mg/g | 5.191 (1.111–24.258) | 4.59 (1) | 32.03 (8) | 0.032 |

| Covariate . | OR (95% CI) . | χ2 (df) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture . | Model . | P-valuea . | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.695 (1.060–6.851) | 4.01 (1) | 4.01 (1) | NA |

| +Age, sex | 3.816 (0.892–16.313) | 3.39 (1) | 6.26 (3) | 0.066 |

| +Diabetes, hypertension | 4.750 (1.118–20.173) | 4.67 (1) | 14.74 (5) | 0.031 |

| +BMI | 4.150 (1.034–16.658) | 4.16 (1) | 19.85 (6) | 0.041 |

| +Family history of KD | 4.378 (1.053–18.197) | 4.31 (1) | 20.51 (7) | 0.038 |

| +ACR >30 mg/g | 5.191 (1.111–24.258) | 4.59 (1) | 32.03 (8) | 0.032 |

Any other self-reported occupation was used as reference group. Age was modelled as a continuous variable. Diabetes and hypertension were defined as a previous medical diagnosis. BMI was modelled as a continuous variable.

Reported P-values correspond to the likelihood ratio test comparing the model with and without agriculture as a covariate, thus effectively assessing the goodness of fit of the tested covariate (i.e. agriculture) for the logistic regression model.

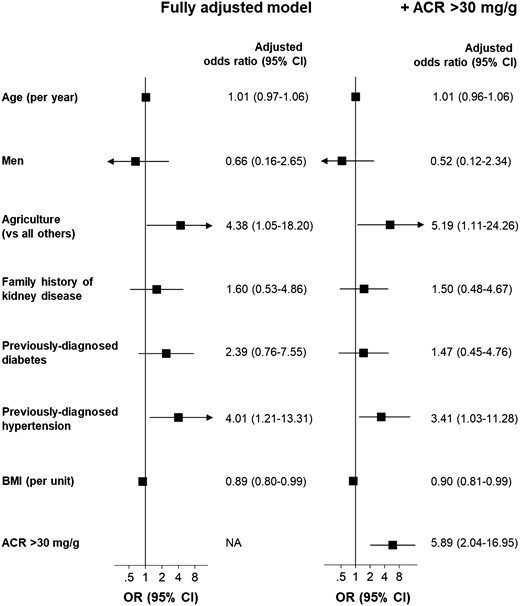

As Figure 2 shows, in this population, working in agriculture and having an ACR >30 mg/g were associated with a 5-fold higher odds of having low eGFR. Additionally, those with hypertension had more than treble the odds of having low eGFR. In contrast, BMI was inversely associated with having lower eGFR, with an OR of 0.90 (95% CI 0.81–0.99) per BMI unit. Previously diagnosed diabetes and family history of KD were positively associated with having low eGFR but were not statistically significant. Further adjustment for ACR did not qualitatively change the results, although the strength of associations of previously diagnosed hypertension and diabetes with having low eGFR was somewhat attenuated.

Odds of having eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and effect of further adjustment for albuminuria. For each variable, the estimated ORs are adjusted for the other shown covariates. Exclusions and conventions are as in Table 1. The eGFR was estimated using Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula and derived from SCr and the ACR was estimated using a semi-quantitative point-of-care device from a random urinary sample. Working in agriculture was not associated with having ACR >30 mg/g (see the Supplementary data, Tables S4 and S5). Unadjusted ORs are available in the Supplementary data, Table S3.

DISCUSSION

We describe the first epidemiological report of kidney function in a middle-aged population (aged 20–60 years) of a possible CKDu hotspot in the Tierra Blanca region, within Mexico. We found that the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of decreased kidney function, defined as a low eGFR (≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2), was 3.5%. Being an agricultural worker was the occupation associated with the highest prevalence of low eGFR (8.8% adjusted prevalence), with almost 1 in every 11 self-reported agricultural workers having low eGFR. In this population, working in agriculture is a factor independently associated with more than a 5-fold risk of having low eGFR [OR 5.2 (1.1–24.3), P = 0.032], after adjustment for age, sex, previously diagnosed diabetes and hypertension, BMI, family history of KD and ACR. Additionally, a quarter of the population (25%) had probable CKD defined as either low eGFR or an ACR >30 mg/g, mostly driven by moderately (30–300 mg/g) and severely (>30 mg/g) increased albuminuria.

Even though our population was very young, our prevalence estimates were substantially higher than in other populations. Reports from the US Renal Data System 2018 for years 2013–16 [19] showed a prevalence of eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2 of 0.4% and 2.8% for ages 20–39 and 40–59 years, respectively, which contrasts with our considerably higher findings of 3.5% in adults aged 20–60 years [1.9% and 4.4% for ages 20–39 and 40–60 years, respectively (Supplementary data, Table S2)]. Furthermore, the prevalence of all CKD (equally defined and measured as our definition of probable CKD) in adults aged >20 years was reportedly at 14.8% in the US population as a whole and 12.6% in the Mexican American population, which are substantially lower than our finding of 25%. Importantly, our study collected data from a population with a high prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and overweight and obesity, all well-known risk factors and causes of KD. However, only half of the cases with low eGFR from our study have an identifiable probable cause of KD, such as diabetes, hypertension or nephrolithiasis. This figure might be an overestimation of cases with an attributable cause, as we had no means of ascertaining if those cases were indeed of diabetic, hypertensive or obstructive nephropathy. Additionally, a family history of KD was reported in 18% of our population and in more than a quarter of the participants with low eGFR. These numbers are significantly higher than what has been reported in other cohorts, where the prevalence of family history varies between 4% and 11% [20, 21]. Even though these highly elevated numbers might partially reflect the awareness of and concern about KD within the sampled population, it is possible that the observed increased prevalence of family history of renal pathologies is due to both socioeconomic and genetic components that cluster in specific families who have become vulnerable and at increased risk of developing CKD. Moreover, assuming the working conditions generating heat stress and dehydration cycles are indeed a cause of KD, it is possible that an overlap between these exposures and traditional risk factors interact and synergistically affect kidney function, thus effectively making of the population of Tierra Blanca—which has a high burden of diabetes, hypertension and adiposity—one at extremely high risk of CKD.

The environmental and working conditions of the Tierra Blanca communities where the study was conducted are very similar to those described CKDu hotspots within regions in Central America. The most outstanding risk factors in patients with CKDu in these regions are thought to be heat stress, cycles of repeated dehydration and extreme labour, although a causal link between these exposures and KD has not yet been established. Isolated episodes of these risk factors, however, can induce acute kidney injury (AKI), and this last condition is in itself an independent risk factor for developing CKD [22, 23]. In fact, SCr levels increase over the work shift in sugar cane workers suggesting episodes of subclinical AKI. More recent reports that included Hispanic (a majority of which were Mexican) agricultural workers in California and Florida have shown that up to a third of the sugar cane workers develop criteria for AKI during a single day-long shift [24, 25]. The risk factors described above are reportedly frequent amongst agricultural workers in Tierra Blanca, but the precise extent to which these working conditions are present and their relationship with kidney function in this population has not been recorded yet. The data from our study, however, underscore the need of exploring this phenomenon further, particularly amongst agricultural workers.

Our study has several strengths, including that it is the first population-based report of a potential CKDu hotspot of major research interest in Mexico and that it was conducted according to the ‘Kidney Early Evaluation Program’ (‘KEEP’) protocol quality standards, which include collecting data directly from the participants by trained health professionals and measuring kidney function tests with appropriate assays such as standardized SCr and ACR. These procedures underpin the generalizability of our findings and facilitate comparisons with other national and international reports. Our study also has limitations. First, it was conducted in the general population and therefore hypertension and diabetes could have accounted for a proportion of the low eGFR prevalence; however, as mentioned above, almost half of the cases did not have any traditional risk factors. Furthermore, working in agriculture was not associated with having an elevated ACR, which is traditionally considered an early biomarker of diabetic nephropathy (Supplementary data, Tables S4 and S5), and further adjustment for ACR did not attenuate the association found between working in agriculture and low eGFR (Figure 2). These findings suggest that the association found between occupation and low eGFR appears not to be confounded by diabetes. Secondly, we did not have a repeated albuminuria or SCr determination for CKD confirmation; however, a longitudinal follow-up of the KEEP Mexico study reported that the percentage of participants who were confirmed as having CKD 1 year after their first screening was 40% for those with CKD Stage 1 at baseline, 52% for those with CKD Stage 2, 67% for those with CKD Stage 3 and 100% for those with CKD Stages 4 and 5. Moreover, the cumulative incidence of CKD at 1 year was 14% amongst those who tested negative in the first screening [26]. In addition, it has been suggested that confirmation of the CKD diagnosis on prevalence studies settled in low- and middle-income countries may not be necessary [27]. Finally, due to logistics constraints, data collection took place mostly during weekdays—Tuesday to Sunday—during working hours. This is likely to be the main underlying reason for men, and agricultural workers, to have been underrepresented in our sample. Therefore, we may have missed cases of individuals with decreased kidney function in these groups. This means, if anything, that our estimates could be an underestimation of the true prevalence. Carrying out a prospective study measuring baseline kidney biomarkers on agricultural workers from Tierra Blanca (preferably amongst disease-free individuals without diabetes and hypertension) and reassessing kidney function after a sensible period (e.g. a harvesting season) would allow further assessments on the incidence of KD, more detailed exposures (e.g. agrochemicals) and working practices in this population.

In conclusion, data from our work in Tierra Blanca suggest that there is a high prevalence of decreased kidney function, particularly in agricultural workers. Further work in this area is needed to confirm and expand our findings.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ndt online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge all the personnel from the Ministry of Health of the State of Veracruz who was involved in the logistics and data collection of the study.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the Ministry of Health of the State of Veracruz and the Research Department from the National Heart Institute ‘Ignacio Chávez’.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. D.A.-R., X.R. and A.V. designed the analysis plan in collaboration with all other co-authors. D.A.-R., A.R.-C. and A.V. conducted the data analysis. All authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data for the work; helped drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A.E., A.R.-C., A.V., D.A.-R., G.T.O., M.M., N.O. and X.R. report non-financial support from the Ministry of Health of the State of Veracrúz, Mexico, during the conduct of the study. R.J.J. reports other sources of funding from Colorado Research Partners, LLC, other from XORTX Therapeutics, personal fees from Horizon Pharma and other from the University of Colorado, outside the submitted work. L.S.-L. reports grants from DANONE RESEARCH and grants from LA ISLA FOUNDATION, outside the submitted work. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract form in the World Congress of Nephrology 2017 in Mexico City. D.A.-R. was affiliated to the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Universidad Panamericana, Mexico, when the present study was conceived and designed, and during data collection and preliminary analyses. The main analyses as well as the interpretation of data and the drafting of the work were done after D.A.-R. moved to the Nuffield Department of Population Health as a DPhil student.

(See related article by Rigothier et al. Chronic kidney disease of unknown origin in agricultural communities: beyond tropical mist? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021; 36: 961–962)

REFERENCES

Versiones. Tierra Blanca, foco rojo por casos de insuficiencia renal: IMSS | Versiones. https://www.versiones.com.mx/tierra-blanca-foco-rojo-por-casos-de-insuficiencia-renal-imss/ (4 March 2018, date last accessed)

United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases,

- hypertension

- body mass index procedure

- kidney diseases

- diabetes mellitus

- renal function

- albumins

- kidney failure, chronic

- creatinine

- agriculture

- biometry

- internship and residency

- mexico

- middle-aged adult

- creatinine tests, serum

- medical residencies

- community

- glomerular filtration rate, estimated

- causality

- albuminuria

- missing data

Comments