-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Juliana Rodrigues, Lilian Cuppari, Katrina L Campbell, Carla Maria Avesani, Nutritional assessment of elderly patients on dialysis: pitfalls and potentials for practice, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 32, Issue 11, November 2017, Pages 1780–1789, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfw471

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The chronic kidney disease (CKD) population is aging. Currently a high percentage of patients treated on dialysis are older than 65 years. As patients get older, several conditions contribute to the development of malnutrition, namely protein energy wasting (PEW), which may be compounded by nutritional disturbances associated with CKD and from the dialysis procedure. Therefore, elderly patients on dialysis are vulnerable to the development of PEW and awareness of the identification and subsequent management of nutritional status is of importance. In clinical practice, the nutritional assessment of patients on dialysis usually includes methods to assess PEW, such as the subjective global assessment, the malnutrition inflammation score, and anthropometric and laboratory parameters. Studies investigating measures of nutritional status specifically tailored to the elderly on dialysis are scarce. Therefore, the same methods and cutoffs used for the general adult population on dialysis are applied to the elderly. Considering this scenario, the aim of this review is to discuss specific considerations for nutritional assessment of elderly patients on dialysis addressing specific shortcomings on the interpretation of markers, in addition to providing clinical practice guidance to assess the nutritional status of elderly patients on dialysis.

INTRODUCTION

Life expectancy has markedly increased over the last century. In 2010, an estimated 524 million people were aged ≥65 years, representing 8% of the world’s population. By 2050, this number is expected to nearly triple to about 1.5 billion, representing 16% of the world population [1]. The demographic of the world aging has a direct impact on the development of noncommunicable diseases, including chronic kidney disease (CKD). The influence of aging on the loss of renal function was shown in a study including individuals aged 70 years and older, in which the prevalence of CKD stages 3, 4 and 5 increased with age, regardless of the coexistence of diabetes and hypertension [2]. The deterioration of renal function in the elderly is caused by the natural process of aging and by the coexistence with other age-related chronic diseases and comorbid conditions that enhance the risk for the loss of renal function [3]. In fact, the latest report from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) 2014 [4] showed that the prevalence of individuals aged 60 years and older with CKD (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) not on dialysis increased from 19.1% to 25.1% from 1988 to 1994 and from 1999 to 2004, respectively, with a slight decrease to 22.7%, from 2007 to 2012. Similarly, the incidence of older individuals starting dialysis in European countries is higher than that of younger ones [5]. Further, with the worldwide increase in life expectancy, a rise in the contingent of elder individuals with CKD is expected.

Senescence is a biological process that leads to a progressive deterioration of structure and function of all organs chronologically, in addition to various age-related disorders. Collectively, it might lead to changes in body composition, which prevails as one of the first alterations related to aging. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown a significant reduction in muscle mass with an increase and redistribution of total body fat with advancing age [6–8]. These age-related changes are of interest especially to elderly patients on dialysis, due to the disturbances from the chronic loss of kidney function and to the dialysis treatment. Moreover, a systematic review focusing on elderly on dialysis showed that impairment of cognitive function, mood, performance status or activities of daily living, mobility (including falls), social environment and poor nutritional status at dialysis initiation were related to poor outcome [9]. Altogether, elderly on dialysis require special attention particularly about their health condition. However, despite the fact that the subject of aging in CKD has gained attention in recent years [3, 10], the guidelines on CKD [11–13] do not explicitly focus on the care of elderly on dialysis. Considering the above, the aim of this review is to critically discuss the nutritional assessment of elderly patients on dialysis and to address specific shortcomings in the methods and on the interpretation of markers used to assess the nutritional status of elderly patients on dialysis. This paper complements a previous review addressing the impact of aging on PEW in patients on dialysis [10].

WHY NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF ELDERLY PATIENTS ON DIALYSIS NEEDS SPECIAL ATTENTION?

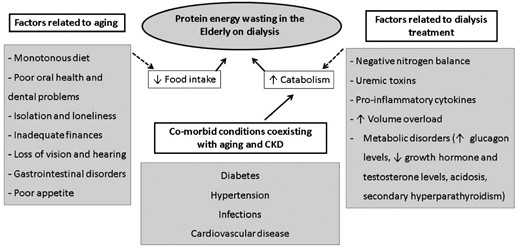

Elderly individuals are prone to the development of malnutrition due to a multifactorial health problem that occurs with aging, which consists of clinical, social and economic aspects, often referred as the ‘nine ds’: dentition, dysgeusia, dysphagia, diarrhea, depression, disease, dementia, dysfunction and drugs [14]. CKD and dialysis treatment can also predispose to malnutrition, named as protein energy wasting (PEW) by the group of experts of the International Society of Renal Nutrition and Metabolism (ISRNM), to reflect the multifaceted etiology [13]. The factors leading to PEW in elderly patients on dialysis were recently described by Johansson and colleagues [10], as summarized in Figure 1, and encompass insufficient food intake and increased protein catabolism related to the aging process, to the disease and to the dialysis treatment. Bearing that in mind, the prevalence of PEW in elderly CKD patients, particularly those under dialysis therapy, is higher when compared with younger patients [15–19]. Moreover, cross-sectional studies have shown a direct association between the prevalence of PEW and age [15, 17, 18]. Finally, a recent study from our group including chronic hemodialysis (CHD) patients older than 60 years showed more than half of the studied sample (58%) had PEW when nutritional status was evaluated by subjective global assessment (SGA) [20]. Considering the high vulnerability of elderly on dialysis to develop PEW and other nutritional-related disorders, the assessment of nutritional status acknowledging the particularities of ageing is of high importance and should be considered by dietitians dealing with this subset of patients.

Common factors related to aging and to dialysis treatment, leading to protein energy wasting.

Sarcopenia and frailty

In addition to PEW, sarcopenia is a common condition in elderly individuals. Recent consensuses in this field defined sarcopenia as the loss of muscle mass and muscle function that occurs with aging with multiple contributing factors, including the coexistence of chronic diseases with advanced organ failure and catabolic conditions [21–24]. As the dialysis treatment leads to a condition of increased protein catabolism [25] and is strongly associated with a sedentary lifestyle [26], patients under dialysis therapy are at risk for developing sarcopenia regardless of the aging process. Since the publication of the sarcopenia consensuses from geriatric societies [21–24], there has been increasing interest in the investigation of its prevalence in the CKD population [27–30]. Kim et al. [29], by applying the definition of sarcopenia from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia for Older People (EWGSOP) in CHD patients aged 50 years and older, observed that 37% of men and 29% of women were sarcopenic. In agreement, Isoyama et al. [28], by applying the same definition, found that 20% of the patients were sarcopenic (mean ± standard deviation age 53.6 ±13 years). Subsequently, a study from our group [27] including patients on CHD aged 60 years and older found a wide prevalence of sarcopenia. When applying the EWGSOP criterion for sarcopenia (i.e. lean body mass assessed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and skinfold thicknesses (SKF) two standard deviations below the mean of young adults and handgrip strength <10th percentile), the prevalence of sarcopenia varied from 3.9% to 30.6%, while by other definitions (low muscle mass defined as below the 20th percentile and handgrip strength below the 10th percentile), it varied from 20.6% to 31.4%. The main issue of sarcopenia in patients on dialysis relies on its association with lower physical activity and with higher mortality risk [28]. In addition, some studies in dialyzed patients have shown that the decreased muscle strength, a criterion to screen for sarcopenia, is associated with worse quality of life, reduced ability to perform daily life activities and high mortality rates [31–33]. Altogether these findings indicate that sarcopenia is a prevalent condition in this segment of patients, which compromises quality of life and leads to higher mortality rates. Until thresholds to screen for low muscle mass, low muscle strength and function are not developed for elderly patients on dialysis, the thresholds suggested for non-CKD elderly proposed by the EWGSOP can be an option to screen for sarcopenia (Table 1).

Methods, measurements and thresholds for the diagnosis of sarcopenia, as suggested by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia for older people [22]

| . | Method . | Measurement . | Threshold . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle mass | DXA | Skeletal muscle mass index (appendicular muscle mass/height2) | Men [34]: 7.26 kg/m2 |

| Women [34]: 5.5 kg/m2 | |||

| BIA | Skeletal muscle mass using BIA-predicted absolute muscle mass equation [35] | Men [36]:

| |

Women [36]:

| |||

| Muscle function | Handgrip strength | Muscle strength | Handgrip [37] |

| Men: <30 kg strength | |||

| Women: <20 kg strength | |||

| Gait speed | Physical performance | <0.8 m/s [37] |

| . | Method . | Measurement . | Threshold . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle mass | DXA | Skeletal muscle mass index (appendicular muscle mass/height2) | Men [34]: 7.26 kg/m2 |

| Women [34]: 5.5 kg/m2 | |||

| BIA | Skeletal muscle mass using BIA-predicted absolute muscle mass equation [35] | Men [36]:

| |

Women [36]:

| |||

| Muscle function | Handgrip strength | Muscle strength | Handgrip [37] |

| Men: <30 kg strength | |||

| Women: <20 kg strength | |||

| Gait speed | Physical performance | <0.8 m/s [37] |

Methods, measurements and thresholds for the diagnosis of sarcopenia, as suggested by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia for older people [22]

| . | Method . | Measurement . | Threshold . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle mass | DXA | Skeletal muscle mass index (appendicular muscle mass/height2) | Men [34]: 7.26 kg/m2 |

| Women [34]: 5.5 kg/m2 | |||

| BIA | Skeletal muscle mass using BIA-predicted absolute muscle mass equation [35] | Men [36]:

| |

Women [36]:

| |||

| Muscle function | Handgrip strength | Muscle strength | Handgrip [37] |

| Men: <30 kg strength | |||

| Women: <20 kg strength | |||

| Gait speed | Physical performance | <0.8 m/s [37] |

| . | Method . | Measurement . | Threshold . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle mass | DXA | Skeletal muscle mass index (appendicular muscle mass/height2) | Men [34]: 7.26 kg/m2 |

| Women [34]: 5.5 kg/m2 | |||

| BIA | Skeletal muscle mass using BIA-predicted absolute muscle mass equation [35] | Men [36]:

| |

Women [36]:

| |||

| Muscle function | Handgrip strength | Muscle strength | Handgrip [37] |

| Men: <30 kg strength | |||

| Women: <20 kg strength | |||

| Gait speed | Physical performance | <0.8 m/s [37] |

Frailty is also an age-related condition often observed in dialyzed patients [38]. It is defined as a syndrome resulting from cumulative deterioration in multiple physiologic systems, leading to impaired homeostatic reserve and decreased capacity to withstand stress [39]. The operational diagnosis of frailty varies, but in the nephrology community the ‘frailty phenotype’ proposed by Fried et al. [40] has been well accepted and includes three of five criterion: weight loss, exhaustion, low physical activity, weak grip strength and slow gait speed. Since the frailty phenotype and sarcopenia share two common criteria, both conditions are inter-related. However, while sarcopenia is a nutrition disturbance, frailty is a condition of disability. Finally, considering the comorbid state of elders on dialysis, it is important to implement methods in the routine practice that account for the identification of PEW, sarcopenia and frailty to plan for adequate therapeutic interventions.

HOW TO ASSESS THE NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF ELDERLY PATIENTS ON DIALYSIS?

The assessment of nutritional status remains one of the main challenges for those working with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. The current nutrition guidelines on dialysis and the ISRNM recommend a range of measurements (Table 2) to improve the precision of the nutritional assessment and the diagnosis of PEW [11–13]. Although most of these measurements are common to young and older adults on dialysis, the interpretation of some can be improved if age-related consequences are also considered, as detailed below.

Recommended measurements for monitoring nutritional status of chronic hemodialysis (CHD) patients from the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQI), European Best Practice Guidelines (EBPG) on Nutrition and the International Society in Renal Nutrition and Metabolism (ISRNM)

| National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQI) [11] . |

|---|

| Measurements that should be performed routinely in all patients: Predialysis serum albumin, % of usual postdialysis body weight and nPNA, % of standard body weight, SGA |

| Measures that can be useful to confirm or extend the data obtained from the previous measures: predialysis or stabilized serum prealbumin, skinfold thickness, mid-arm muscle area, circumference, DXA |

| Clinically useful measures, which, if low, might suggest the need for a more rigorous examination of protein-energy nutritional status: predialysis or stabilized serum: creatinine, urea nitrogen, cholesterol; and creatinine index |

| EBPG on Nutrition [12] |

| Malnutrition should be diagnosed by a number of assessment tools including: dietary assessment, BMI, SGA, anthropometry, nPNA, serum albumin and serum prealbumin, serum cholesterol and technical investigations of body composition (BIA, DXA, near infrared reactance) |

| ISRNM [13] |

| Potential tools (including those still in development) for the clinical diagnosis of PEW in individuals with CKD. At least three out of the four listed categories (and at least one test in each of the selected category) must be satisfied for the diagnosis of kidney disease-related PEW: serum chemistry: serum albumin, serum prealbumin (transthyretin) and serum cholesterol |

| Body mass: BMI, unintentional weight loss and total body fat percentage |

| Muscle mass: muscle mass (reduced muscle mass over time), reduced mid-arm muscle circumference area, creatinine appearance |

| Dietary intake: unintentional low dietary protein and energy intake |

| National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQI) [11] . |

|---|

| Measurements that should be performed routinely in all patients: Predialysis serum albumin, % of usual postdialysis body weight and nPNA, % of standard body weight, SGA |

| Measures that can be useful to confirm or extend the data obtained from the previous measures: predialysis or stabilized serum prealbumin, skinfold thickness, mid-arm muscle area, circumference, DXA |

| Clinically useful measures, which, if low, might suggest the need for a more rigorous examination of protein-energy nutritional status: predialysis or stabilized serum: creatinine, urea nitrogen, cholesterol; and creatinine index |

| EBPG on Nutrition [12] |

| Malnutrition should be diagnosed by a number of assessment tools including: dietary assessment, BMI, SGA, anthropometry, nPNA, serum albumin and serum prealbumin, serum cholesterol and technical investigations of body composition (BIA, DXA, near infrared reactance) |

| ISRNM [13] |

| Potential tools (including those still in development) for the clinical diagnosis of PEW in individuals with CKD. At least three out of the four listed categories (and at least one test in each of the selected category) must be satisfied for the diagnosis of kidney disease-related PEW: serum chemistry: serum albumin, serum prealbumin (transthyretin) and serum cholesterol |

| Body mass: BMI, unintentional weight loss and total body fat percentage |

| Muscle mass: muscle mass (reduced muscle mass over time), reduced mid-arm muscle circumference area, creatinine appearance |

| Dietary intake: unintentional low dietary protein and energy intake |

nPNA, normalized protein equivalent of nitrogen appearance.

Recommended measurements for monitoring nutritional status of chronic hemodialysis (CHD) patients from the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQI), European Best Practice Guidelines (EBPG) on Nutrition and the International Society in Renal Nutrition and Metabolism (ISRNM)

| National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQI) [11] . |

|---|

| Measurements that should be performed routinely in all patients: Predialysis serum albumin, % of usual postdialysis body weight and nPNA, % of standard body weight, SGA |

| Measures that can be useful to confirm or extend the data obtained from the previous measures: predialysis or stabilized serum prealbumin, skinfold thickness, mid-arm muscle area, circumference, DXA |

| Clinically useful measures, which, if low, might suggest the need for a more rigorous examination of protein-energy nutritional status: predialysis or stabilized serum: creatinine, urea nitrogen, cholesterol; and creatinine index |

| EBPG on Nutrition [12] |

| Malnutrition should be diagnosed by a number of assessment tools including: dietary assessment, BMI, SGA, anthropometry, nPNA, serum albumin and serum prealbumin, serum cholesterol and technical investigations of body composition (BIA, DXA, near infrared reactance) |

| ISRNM [13] |

| Potential tools (including those still in development) for the clinical diagnosis of PEW in individuals with CKD. At least three out of the four listed categories (and at least one test in each of the selected category) must be satisfied for the diagnosis of kidney disease-related PEW: serum chemistry: serum albumin, serum prealbumin (transthyretin) and serum cholesterol |

| Body mass: BMI, unintentional weight loss and total body fat percentage |

| Muscle mass: muscle mass (reduced muscle mass over time), reduced mid-arm muscle circumference area, creatinine appearance |

| Dietary intake: unintentional low dietary protein and energy intake |

| National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQI) [11] . |

|---|

| Measurements that should be performed routinely in all patients: Predialysis serum albumin, % of usual postdialysis body weight and nPNA, % of standard body weight, SGA |

| Measures that can be useful to confirm or extend the data obtained from the previous measures: predialysis or stabilized serum prealbumin, skinfold thickness, mid-arm muscle area, circumference, DXA |

| Clinically useful measures, which, if low, might suggest the need for a more rigorous examination of protein-energy nutritional status: predialysis or stabilized serum: creatinine, urea nitrogen, cholesterol; and creatinine index |

| EBPG on Nutrition [12] |

| Malnutrition should be diagnosed by a number of assessment tools including: dietary assessment, BMI, SGA, anthropometry, nPNA, serum albumin and serum prealbumin, serum cholesterol and technical investigations of body composition (BIA, DXA, near infrared reactance) |

| ISRNM [13] |

| Potential tools (including those still in development) for the clinical diagnosis of PEW in individuals with CKD. At least three out of the four listed categories (and at least one test in each of the selected category) must be satisfied for the diagnosis of kidney disease-related PEW: serum chemistry: serum albumin, serum prealbumin (transthyretin) and serum cholesterol |

| Body mass: BMI, unintentional weight loss and total body fat percentage |

| Muscle mass: muscle mass (reduced muscle mass over time), reduced mid-arm muscle circumference area, creatinine appearance |

| Dietary intake: unintentional low dietary protein and energy intake |

nPNA, normalized protein equivalent of nitrogen appearance.

Of special interest, conditions related to aging should be incorporated in the form of the nutritional assessment of elderly patients on dialysis (Table 3). It encompasses poor dentition, maladapted dental prostheses and problems in chewing, besides social and clinical aspects that also interfere with food intake, such as low economic income, living alone, limitations to acquiring and preparing food, the presence of comorbidities and the use of medication. Also of importance particularly to elderly individuals is the assessment of unintentional weight loss, which is part of screening tools for the assessment of nutritional status [SGA, malnutrition inflammation score (MIS) and mini nutritional assessment (MNA)]. Unintentional weight loss in the elderly can be attributed to several factors related to aging and mostly by the presence of anorexia and catabolic diseases, which may lead to loss of muscle mass and development of PEW, sarcopenia and frailty [40]. In CKD, the implication of weight changes over a period of 6 months was investigated by Cabezas-Rodriguez et al. [45] in a study including 20 European countries. The authors showed that patients who lost weight had an increased risk of mortality when compared with those who did not. In addition, when analyzing by age stratum, those older than 65 years who lost body weight had a higher risk of death than the younger ones [45]. Collectively, these results indicate that early prevention and identification of weight loss are crucial to improve the overall nutritional status, as well as to diminish the mortality risk.

| Method . | Aim . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive tools | ||

| SGA and MIS | Diagnosis of PEW | The physical examination, present in SGA and MIS, requires special attention when performed in the elderly. Be aware that the elderly often show increased body fat in the trunk, even though muscle mass is decreased. In addition, elderly patients often show more skin, which should not be confounded with fat or muscle, mainly around arms and below the eyes. Adding specific questions related to aging (see questions placed at the end of this table) is of importance. Both instruments require training to diminish intra- and inter-individual variation. |

| MNA | Screening and diagnosis of PEW | Developed for non-CKD elderly. The short-MNA is a screening tool, while the full-MNA has an indicator score of malnutrition. The full-MNA performed better than the short-MNA form in PD patients [41]. There are not many studies applying the MNA in elderly patients on dialysis. |

| Anthropometrya | ||

| Skinfold thicknesses | Fat mass assessment | When pinching the skinfold, one should be careful not to cofound the excess of skin normally present in the elderly with fat. |

| Calf circumference | Muscle mass assessment | One should be alert for the presence of clinical edema in the legs, a condition that will mislead the interpretation of this measurement. This measurement has been well accepted for the assessment of low muscle mass in non-CKD elderly [42]. |

| Knee height | Stature measurement | It is of importance to correct for the difference in stature that occurs with aging. It is suggested to be used when using an index, such as BMI, as well in equations, such as for estimating basal metabolic rate, often used to calculate the energy needs. |

| BIA and BIS | Muscle mass assessment | By using specific equations well accepted for sarcopenia assessment, skeletal muscle mass can be estimated [35]. The assessment of lean body mass by BIA from equations not validated to dialyzed patients can lead to misleading interpretation. The estimation of lean body mass by BIS, on the other hand, has shown better agreement with reference methods in dialyzed patients. Studies testing the usefulness of BIS in elderly patients on dialysis are needed. Measurements should be performed after the hemodialysis session or with an empty cavity for PD patients to diminish the influence of hydration status [43]. |

| Handgrip strength | Muscle strength assessment | Assessment of muscle function. Well accepted as a criterion for the diagnosis of sarcopenia and frailty. |

| Dietary intake | ||

| 24-h food recall, food registries and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire | Estimative of energy, protein, electrolytes and vitamins intake | Memory loss and blurred vision, conditions often observed in elderly, can compromise evaluation by retrospective methods (24-h food record and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire). Information provided by the patient’s accompanier, including frequency of meals, portion size, food preferences and aversions, allergies and food consistency are important to complement the food intake assessment of elderly. |

| PNA | Protein intake | Under a catabolic condition (inflammation, infection and concurrent comorbidities), the PNA will be higher than the actual protein intake. It does not provide information on the quality of the protein and food habits. Therefore, the usual methods for the assessment of dietary intake should not be replaced for PNA. |

| General questions related to aging to be incorporated in the nutritional assessment form | Complement the nutritional assessment of elderly | Questions related to dentition, maladapted dental proteases, problems in chewing, social and clinical condition (low economic income, living alone, limitations to acquiring and preparing food), presence of comorbidities and use of medications that interfere with nutrients absorption should be included in the nutritional assessment forms of elderly on dialysis. Unintentional weight loss over a period of 3–6 months is commonly assessed in non-CKD elderly and is highly correlated with higher mortality rates [44]. |

| Serum albumin and pre-albumin | Mortality prognostic factor | Concentration of serum albumin can be affected by high volume overload, inflammatory process, comorbidities and by malnutrition. The inverse relationship of serum albumin and poor outcome has been described in several papers in the CKD field, but not in the elderly on dialysis. Studies on elderly non-CKD showed that serum albumin tends to be lower than that in younger individuals. |

| Method . | Aim . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive tools | ||

| SGA and MIS | Diagnosis of PEW | The physical examination, present in SGA and MIS, requires special attention when performed in the elderly. Be aware that the elderly often show increased body fat in the trunk, even though muscle mass is decreased. In addition, elderly patients often show more skin, which should not be confounded with fat or muscle, mainly around arms and below the eyes. Adding specific questions related to aging (see questions placed at the end of this table) is of importance. Both instruments require training to diminish intra- and inter-individual variation. |

| MNA | Screening and diagnosis of PEW | Developed for non-CKD elderly. The short-MNA is a screening tool, while the full-MNA has an indicator score of malnutrition. The full-MNA performed better than the short-MNA form in PD patients [41]. There are not many studies applying the MNA in elderly patients on dialysis. |

| Anthropometrya | ||

| Skinfold thicknesses | Fat mass assessment | When pinching the skinfold, one should be careful not to cofound the excess of skin normally present in the elderly with fat. |

| Calf circumference | Muscle mass assessment | One should be alert for the presence of clinical edema in the legs, a condition that will mislead the interpretation of this measurement. This measurement has been well accepted for the assessment of low muscle mass in non-CKD elderly [42]. |

| Knee height | Stature measurement | It is of importance to correct for the difference in stature that occurs with aging. It is suggested to be used when using an index, such as BMI, as well in equations, such as for estimating basal metabolic rate, often used to calculate the energy needs. |

| BIA and BIS | Muscle mass assessment | By using specific equations well accepted for sarcopenia assessment, skeletal muscle mass can be estimated [35]. The assessment of lean body mass by BIA from equations not validated to dialyzed patients can lead to misleading interpretation. The estimation of lean body mass by BIS, on the other hand, has shown better agreement with reference methods in dialyzed patients. Studies testing the usefulness of BIS in elderly patients on dialysis are needed. Measurements should be performed after the hemodialysis session or with an empty cavity for PD patients to diminish the influence of hydration status [43]. |

| Handgrip strength | Muscle strength assessment | Assessment of muscle function. Well accepted as a criterion for the diagnosis of sarcopenia and frailty. |

| Dietary intake | ||

| 24-h food recall, food registries and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire | Estimative of energy, protein, electrolytes and vitamins intake | Memory loss and blurred vision, conditions often observed in elderly, can compromise evaluation by retrospective methods (24-h food record and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire). Information provided by the patient’s accompanier, including frequency of meals, portion size, food preferences and aversions, allergies and food consistency are important to complement the food intake assessment of elderly. |

| PNA | Protein intake | Under a catabolic condition (inflammation, infection and concurrent comorbidities), the PNA will be higher than the actual protein intake. It does not provide information on the quality of the protein and food habits. Therefore, the usual methods for the assessment of dietary intake should not be replaced for PNA. |

| General questions related to aging to be incorporated in the nutritional assessment form | Complement the nutritional assessment of elderly | Questions related to dentition, maladapted dental proteases, problems in chewing, social and clinical condition (low economic income, living alone, limitations to acquiring and preparing food), presence of comorbidities and use of medications that interfere with nutrients absorption should be included in the nutritional assessment forms of elderly on dialysis. Unintentional weight loss over a period of 3–6 months is commonly assessed in non-CKD elderly and is highly correlated with higher mortality rates [44]. |

| Serum albumin and pre-albumin | Mortality prognostic factor | Concentration of serum albumin can be affected by high volume overload, inflammatory process, comorbidities and by malnutrition. The inverse relationship of serum albumin and poor outcome has been described in several papers in the CKD field, but not in the elderly on dialysis. Studies on elderly non-CKD showed that serum albumin tends to be lower than that in younger individuals. |

All anthropometric measures require training to diminish intra- and inter-individual variation. Measurements should be performed after the hemodialysis session when the patient is closer to the dry body weight.

| Method . | Aim . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive tools | ||

| SGA and MIS | Diagnosis of PEW | The physical examination, present in SGA and MIS, requires special attention when performed in the elderly. Be aware that the elderly often show increased body fat in the trunk, even though muscle mass is decreased. In addition, elderly patients often show more skin, which should not be confounded with fat or muscle, mainly around arms and below the eyes. Adding specific questions related to aging (see questions placed at the end of this table) is of importance. Both instruments require training to diminish intra- and inter-individual variation. |

| MNA | Screening and diagnosis of PEW | Developed for non-CKD elderly. The short-MNA is a screening tool, while the full-MNA has an indicator score of malnutrition. The full-MNA performed better than the short-MNA form in PD patients [41]. There are not many studies applying the MNA in elderly patients on dialysis. |

| Anthropometrya | ||

| Skinfold thicknesses | Fat mass assessment | When pinching the skinfold, one should be careful not to cofound the excess of skin normally present in the elderly with fat. |

| Calf circumference | Muscle mass assessment | One should be alert for the presence of clinical edema in the legs, a condition that will mislead the interpretation of this measurement. This measurement has been well accepted for the assessment of low muscle mass in non-CKD elderly [42]. |

| Knee height | Stature measurement | It is of importance to correct for the difference in stature that occurs with aging. It is suggested to be used when using an index, such as BMI, as well in equations, such as for estimating basal metabolic rate, often used to calculate the energy needs. |

| BIA and BIS | Muscle mass assessment | By using specific equations well accepted for sarcopenia assessment, skeletal muscle mass can be estimated [35]. The assessment of lean body mass by BIA from equations not validated to dialyzed patients can lead to misleading interpretation. The estimation of lean body mass by BIS, on the other hand, has shown better agreement with reference methods in dialyzed patients. Studies testing the usefulness of BIS in elderly patients on dialysis are needed. Measurements should be performed after the hemodialysis session or with an empty cavity for PD patients to diminish the influence of hydration status [43]. |

| Handgrip strength | Muscle strength assessment | Assessment of muscle function. Well accepted as a criterion for the diagnosis of sarcopenia and frailty. |

| Dietary intake | ||

| 24-h food recall, food registries and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire | Estimative of energy, protein, electrolytes and vitamins intake | Memory loss and blurred vision, conditions often observed in elderly, can compromise evaluation by retrospective methods (24-h food record and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire). Information provided by the patient’s accompanier, including frequency of meals, portion size, food preferences and aversions, allergies and food consistency are important to complement the food intake assessment of elderly. |

| PNA | Protein intake | Under a catabolic condition (inflammation, infection and concurrent comorbidities), the PNA will be higher than the actual protein intake. It does not provide information on the quality of the protein and food habits. Therefore, the usual methods for the assessment of dietary intake should not be replaced for PNA. |

| General questions related to aging to be incorporated in the nutritional assessment form | Complement the nutritional assessment of elderly | Questions related to dentition, maladapted dental proteases, problems in chewing, social and clinical condition (low economic income, living alone, limitations to acquiring and preparing food), presence of comorbidities and use of medications that interfere with nutrients absorption should be included in the nutritional assessment forms of elderly on dialysis. Unintentional weight loss over a period of 3–6 months is commonly assessed in non-CKD elderly and is highly correlated with higher mortality rates [44]. |

| Serum albumin and pre-albumin | Mortality prognostic factor | Concentration of serum albumin can be affected by high volume overload, inflammatory process, comorbidities and by malnutrition. The inverse relationship of serum albumin and poor outcome has been described in several papers in the CKD field, but not in the elderly on dialysis. Studies on elderly non-CKD showed that serum albumin tends to be lower than that in younger individuals. |

| Method . | Aim . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive tools | ||

| SGA and MIS | Diagnosis of PEW | The physical examination, present in SGA and MIS, requires special attention when performed in the elderly. Be aware that the elderly often show increased body fat in the trunk, even though muscle mass is decreased. In addition, elderly patients often show more skin, which should not be confounded with fat or muscle, mainly around arms and below the eyes. Adding specific questions related to aging (see questions placed at the end of this table) is of importance. Both instruments require training to diminish intra- and inter-individual variation. |

| MNA | Screening and diagnosis of PEW | Developed for non-CKD elderly. The short-MNA is a screening tool, while the full-MNA has an indicator score of malnutrition. The full-MNA performed better than the short-MNA form in PD patients [41]. There are not many studies applying the MNA in elderly patients on dialysis. |

| Anthropometrya | ||

| Skinfold thicknesses | Fat mass assessment | When pinching the skinfold, one should be careful not to cofound the excess of skin normally present in the elderly with fat. |

| Calf circumference | Muscle mass assessment | One should be alert for the presence of clinical edema in the legs, a condition that will mislead the interpretation of this measurement. This measurement has been well accepted for the assessment of low muscle mass in non-CKD elderly [42]. |

| Knee height | Stature measurement | It is of importance to correct for the difference in stature that occurs with aging. It is suggested to be used when using an index, such as BMI, as well in equations, such as for estimating basal metabolic rate, often used to calculate the energy needs. |

| BIA and BIS | Muscle mass assessment | By using specific equations well accepted for sarcopenia assessment, skeletal muscle mass can be estimated [35]. The assessment of lean body mass by BIA from equations not validated to dialyzed patients can lead to misleading interpretation. The estimation of lean body mass by BIS, on the other hand, has shown better agreement with reference methods in dialyzed patients. Studies testing the usefulness of BIS in elderly patients on dialysis are needed. Measurements should be performed after the hemodialysis session or with an empty cavity for PD patients to diminish the influence of hydration status [43]. |

| Handgrip strength | Muscle strength assessment | Assessment of muscle function. Well accepted as a criterion for the diagnosis of sarcopenia and frailty. |

| Dietary intake | ||

| 24-h food recall, food registries and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire | Estimative of energy, protein, electrolytes and vitamins intake | Memory loss and blurred vision, conditions often observed in elderly, can compromise evaluation by retrospective methods (24-h food record and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire). Information provided by the patient’s accompanier, including frequency of meals, portion size, food preferences and aversions, allergies and food consistency are important to complement the food intake assessment of elderly. |

| PNA | Protein intake | Under a catabolic condition (inflammation, infection and concurrent comorbidities), the PNA will be higher than the actual protein intake. It does not provide information on the quality of the protein and food habits. Therefore, the usual methods for the assessment of dietary intake should not be replaced for PNA. |

| General questions related to aging to be incorporated in the nutritional assessment form | Complement the nutritional assessment of elderly | Questions related to dentition, maladapted dental proteases, problems in chewing, social and clinical condition (low economic income, living alone, limitations to acquiring and preparing food), presence of comorbidities and use of medications that interfere with nutrients absorption should be included in the nutritional assessment forms of elderly on dialysis. Unintentional weight loss over a period of 3–6 months is commonly assessed in non-CKD elderly and is highly correlated with higher mortality rates [44]. |

| Serum albumin and pre-albumin | Mortality prognostic factor | Concentration of serum albumin can be affected by high volume overload, inflammatory process, comorbidities and by malnutrition. The inverse relationship of serum albumin and poor outcome has been described in several papers in the CKD field, but not in the elderly on dialysis. Studies on elderly non-CKD showed that serum albumin tends to be lower than that in younger individuals. |

All anthropometric measures require training to diminish intra- and inter-individual variation. Measurements should be performed after the hemodialysis session when the patient is closer to the dry body weight.

Body mass index

Among the measurements listed in Table 2, body mass index (BMI) is particularly contested when applied in the elderly [46]. BMI is used in clinical practice due to its ease of measurement and strong association with markers of body fatness in the general adult population [47]. However, its interpretation to assess nutrition status is compromised by the inability to assess the distribution of body composition, and particular to the elderly are the change in height that occurs with aging [48]. For ESRD patients, differentiating body fat from lean mass and volume overload are important issues that compromise the use of BMI. In addition, the increase in body fat percentage with concomitant decrease in muscle mass that occurs with aging can lead to the misclassification of non-obese when nutritional status is assessed by BMI [49]. Under this rationale, our group has recently tested the performance of the BMI thresholds proposed by the WHO (>30 kg/m2) and by the Nutrition Screening Initiative (NSI) (>27 kg/m2) to diagnose obesity in elderly patients on CHD. The NSI is a national collaborative effort committed to the identification and treatment of nutritional problems in older persons that proposed a checklist, including BMI thresholds different from that of WHO, to increase awareness to detect nutritional risk among older people in different settings [50]. Our study showed that taking body fat percentage as a reference to diagnose obesity, the WHO-BMI thresholds underestimated obesity in men, while the NSI-BMI thresholds tended to overestimate obesity in men and women [51]. Moreover, both thresholds had low-to-moderate agreement for the assessment of obesity using the sum of skinfold thicknesses and waist circumference as markers of body fatness.

In addition to the assessment of body fatness, the WHO proposed a BMI <18.5 kg/m2 to the general population to discriminate for low body weight [47]. This low BMI may be relevant for the elderly, at least those aged from 60 to 69 years, but whether different cutoffs are more appropriate in individuals 70 years or older is uncertain [52]. In the general CKD population, regardless of the age stratum, a higher threshold of BMI (<23 kg/m2) has been recommended to screen for PEW in conjunction with other nutritional markers [12, 13]. However, whether this value can discriminate for PEW in CKD patients it is still a matter of debate [53, 54]. In summary, although BMI is suitable for clinical practice, its value as marker of nutritional status (for both PEW and obesity) in CKD is uncertain, particularly when applied to elderly individuals. Hence, measurements of body fat suitable for clinical practice (i.e. skinfold thicknesses and waist circumference) are suggested to avoid spurious interpretation of BMI to assess the nutritional status in elderly on dialysis. In addition, methods that enable assessment of the presence of PEW are desirable.

Comprehensive tools for the assessment of PEW

SGA, MIS and MNA are methods able to assess for PEW, providing a comprehensive assessment also of the degree of malnutrition. SGA involves evaluation of subjective and objective aspects of nutritional status, including a structured medical history and physical examination to provide a global nutrition status rating. It is a simple and inexpensive tool that can be applied by trained healthcare professionals. The MIS is comprised of 10 components, building on the SGA with a score, and an additional three items (serum albumin, iron binding capacity and BMI). SGA and MIS have been largely applied in clinical studies including CKD patients [17, 18, 20, 55, 56] and are recommended by the current guidelines on nutrition to identify PEW in patients on dialysis [11, 12]. MNA, on the other hand, is originally designed for the elderly non-CKD population. It is comprised of a screening section (six questions), known as MNA-short form, which can be further complemented by 11 questions in order to gain a malnutrition indicator score scale (full-MNA form) [57].

Comparative studies of the various assessment tools have been conducted in the CKD population; however, there is a paucity of these studies focused solely on the elderly. The ability of the full- and short-form MNA to assess PEW in adult dialyzed patients was investigated [58, 41]. Brzosko et al. [58] aiming to validate the full-MNA in adults (55 ± 11 years) on peritoneal dialysis found that MNA was highly correlated with MIS (r = –0.85, P < 0.01, ANOVA, P < 0.01). Another study that investigated the convergent validity in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients with risk of PEW observed that the full-MNA, followed by the MNA-short form, performed better than SGA in differentiating patients with PEW [41]. However, most of the studies included patients with a wide age range (18 years and older) impairing the assessment of the ability of these methods to screen for PEW in elders on dialysis. With that in mind, Santin et al. [20] assessed the performance of SGA, MIS and MNA-short form in elderly patients on CHD (≥60 years) by evaluating their concurrent and predictive validity. The authors observed that the elderly patients identified as having PEW by SGA, MIS and MNA-short form had worse objective nutritional parameters (anthropometrics measurements, phase angle and serum albumin) than those identified as well nourished [20], indicating good concurrent validity. In addition, it was also reported that elderly patients with PEW had higher mortality risk using all three tools, suggesting a good predictive validity as well [20]. Moreover, these findings indicate that similar to what has been observed in adults on dialysis, SGA and MIS performed well for the diagnosis of PEW in elderly patients on CHD. However, these methods are highly reliant upon the observer’s skills and training. This is especially pertinent for the elderly when performing the physical examination, as they often show increased body fatness, mainly in the trunk, which makes it more difficult to detect low muscle mass. Therefore, it is desirable that the observer develops specific skills when performing the physical examination of body fat and muscle mass in elders. The assessment of body composition can be of particular interest for elders on dialysis to complement the assessment by SGA, MIS or MNA.

BODY COMPOSITION ASSESSMENT

Aging per se implies in a series of changes on body composition, which includes the increase of body fat mass, decrease of lean body mass and bone mineral density, and fat infiltration in muscle [59]. Moreover, there is an important redistribution of body fat, with a higher concentration in the abdominal region [8, 59]. Therefore, a periodical assessment of body composition, including the evaluation of body fat, lean mass and body fat distribution, is of importance.

Methods to assess body composition encompass those with higher applicability for clinical practice, as well as those with higher precision and more suitable for research. The methods with higher precision include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), DXA, total body potassium and neutron activation analysis—total body nitrogen. In addition to the advantage of their high precision, DXA, CT and MRI allow the assessment of bone mineral content, and lean and fat tissue separately by body segment and DXA also assesses total body composition. Moreover, CT and MRI can further the body composition assessment by describing skeletal muscle, fat infiltration in the muscle, subcutaneous fat and visceral fat (the last one depending on the body slice assessed).

Considering the age-related changes in body composition, the assessment by these techniques can add important information for descriptive purposes and interventional studies related to diet and exercise, as well as for survival analysis. In fact, Fukasawa et al. [60] demonstrated that lower thigh muscle area (assessed by CT) in elderly on CHD was associated with higher cardiovascular mortality, although no such association was found with thigh fat, abdominal muscle and fat mass levels, hypothesizing that interventional studies focusing the muscle mass of lower extremities are important to improve clinical outcomes. However, due to the high cost and exposition of radiation (DXA and CT), these imaging methods are not available for clinical practice purposes. To this end, the assessment of skinfold thickness at four sites (triceps, biceps, subscapular and iliac crest) and BIA stand as alternatives to evaluate body composition based on the two-compartment model (estimation of fat and fat-free mass) [39]. However, both methods are subject to estimative errors due to the reliance on equations not validated for a specific subset of patients, particularly for use in the elderly.

Errors in the estimation of body fat from skinfolds relate to the reference populations used to develop the conversion equations. For instance, the equations from Durnin and Womersley [61] applied to assess body density from the sum of skinfold thicknesses are based on a group of individuals aged between 16 and 72 years old, and the sample size for individuals older than 50 years old was small (n = 61/481; 13%). The Siri equation applied to assess body fat percentage from the body density [62] was developed from a database including young individuals. In addition, this procedure is based on the assumption that there is a linear association between total fat, subcutaneous fat and body density. Nevertheless, the correlation between the subcutaneous and total body fat decreases with age resulting from the redistribution of the fat mass from the extremity to the visceral areas and due to the replacement of muscle tissue to intramuscular fat [48]. Therefore, body density can be overestimated and body fat underestimated in the elderly population aged >75 years.

Even acknowledging the limitations of the assessment of body composition by skinfold thickness and BIA for patients aged >75 years, these methods are still a plausible alternative, until methods that gather characteristics with higher precision and suitable for clinical practice are available. Potential anthropometric measurements that require further testing in patients on dialysis that have been largely applied in elderly non-CKD include the knee height to estimate height and the calf circumference as surrogate of muscle mass. Knee height is of interest to correct for the reduction on the measured height that occurs with aging [63, 64]. Such correction is of importance because height is used in equations to estimate the body composition and to calculate the BMI and the resting metabolic rate, often used to estimate energy needs. Calf circumference is another potential tool to be assessed in the elderly on dialysis, as long as there is no clinical edema. Landi et al. [65] observed that frailty severity, physical performance and functional status improved significantly as calf circumference increased in non-CKD elderly persons aged ≥80 years. In addition, frail subjects presented a lower calf circumference when compared with non-frail subjects (30.4 ± 6.2 versus 33.3 ± 4.1, respectively; P < 0.001). In accordance, a study by Rolland et al. [42] of elderly women older than 69 years observed that individuals with calf circumference <31 cm had clinical signs of sarcopenia, disability and self-reported low physical functioning independently of age, comorbidity, obesity, income, health behavior and visual impairment. Therefore, the use of calf circumference and the knee height in elderly patients on dialysis can add information about the health status of these patients and also allow a more accurate assessment of the nutritional status and body composition.

Regarding BIA, there are several bioimpedance techniques that are classified as single or multi-frequency electrical current and as whole-body or segmental. Similar to the previous method, BIA manufacturers rely on equations that are not validated in populations with similar biological and clinical characteristics, and estimative errors can be observed. Thus, when extrapolating these equations to different populations, especially for the elderly on dialysis, one should search for equations based on a population with similar biological and clinical characteristics. In addition, fluid overload, a condition often observed in dialyzed patients, can lead to errors in the assessment of body composition by BIA. Of note, the single-frequency BIA models have been often replaced by bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy (BIS) (with electrical current raging from 5 to 1000 KHz), due to its higher precision for the assessment of the extracellular and total body water in dialyzed patients [66, 67], which can reduce the inaccuracy on the estimation of lean and fat mass. It is important that the assessment of body composition by BIA and BIS should be performed after the dialysis session on CHD patients or with an empty cavity on PD patients in order to minimize errors [39]. We are not aware of studies testing the use of BIA in elderly patients on dialysis.

A further concern regarding the evaluation of body composition of elderly individuals refers to the thresholds used to classify individuals as well nourished, malnourished or obese. Tables used to classify the nutritional status of elderly individuals including different nationalities are scarce, mostly representing the elderly from developed countries, which is not representative of a global portion of elderly individuals worldwide. In addition, the normality tables available from Frisancho do not include the oldest elders aged ≥75 years [68]. Hence, longitudinal measurements in the same patient may provide useful information on trends of body composition changes in order to minimize the errors coming from the lack of normality tables appropriate for older patients on dialysis.

DIETARY INTAKE

Of importance for the assessment of nutritional status is the evaluation of food intake. Twenty-four-hour food recall, food records and the semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire have been traditionally applied to estimate the energy, protein, electrolytes and vitamins intakes in CKD and ESRD patients. However, when applied in a group of elderly patients, these methods are subject to limitations related to aging (e.g. memory loss and blurred vision), which can compromise evaluation by retrospective methods (24-h food record and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire) and fulfilling the food record form [69]. To account for these age-related limitations, the patient’s accompanying person is often required to provide additional information related to the food history, including frequency of meals, portion size, food preferences and aversions, allergies and food consistency.

The protein equivalent of total nitrogen appearance (PNA), previously known as protein catabolic rate, can be a useful method to estimate the protein intake. It is based on the concept that nitrogen arising from the degraded protein is excreted as either urea or non-urea nitrogen [70]. Because urea is the main end-product of amino acid degradation, the urea appearance rate (or net urea production rate) parallels the protein intake. The urea nitrogen appearance rate is measured from the urea excreted in the urine plus the urea that is accumulated in body water. Patients on dialysis without diuresis have the urea nitrogen appearance estimated from the pool of urea nitrogen generated in the interdialysis period by using estimated equations [70]. The PNA has the advantage of not depending on the patient’s information and therefore can be useful in the elderly to correct for some of the age-related limitations of methods of food intake assessment. However, if the patient is under a catabolic condition (inflammation, infection and concurrent comorbidities), the urea nitrogen production will be higher than the actual protein intake and will not reflect the usual intake [71]. Hence, the use of PNA does not exclude a detailed assessment of the patient’s intake of protein, energy and other nutrients by the traditional methods that assess dietary intake.

SERUM PROTEINS

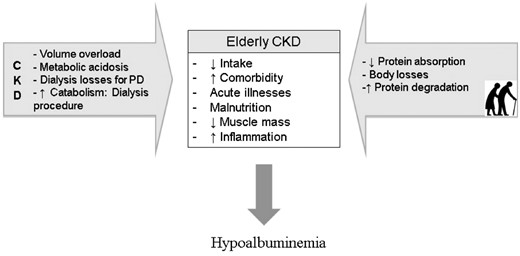

Serum albumin and pre-albumin (transthyretin, which is a preferred term) concentration, like all body proteins, is the result of simultaneous physiologic process of synthesis and catabolism. In CKD, hypoalbuminemia is a frequent finding [72], but little is known about serum albumin or pre-albumin of elderly on dialysis. Similar to non-CKD individuals, CKD patients present analogous factors regulating the hepatic synthesis and catabolism of serum albumin, which includes compromised protein intake and nutrient absorption, raised serum concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines, alterations in the volume of distribution (including hemodilution), protein degradation, body losses, comorbidities, malnutrition, sarcopenia and aging [73, 74]. In patients on dialysis, metabolic acidosis, inflammation and the losses incurred through the dialysis procedure are three of the main factors leading to hypoalbuminemia [75] (Figure 2). The influence of aging as a factor regulating serum albumin has not been investigated yet. We found two studies that compared the nutritional status of young (<65 years) versus elderly (≥65 years) CHD patients [16, 19]. Although both studies applied similar eligibility criteria, excluding patients with acute illnesses and infections, the results were contradictory. Although Çelik et al. [16] found that serum albumin was significantly lower in the elderly than in the young group, Lee et al. [19] found similar albumin levels between both groups. Of note, both studies failed to find a significant association between age and serum albumin. Although merely speculative, the hydration status might partially explain the contradictory results, since in the study that failed to find differences in the serum albumin between older versus younger patients, the hydration status showed a higher ratio of extracellular water to total body water in the elderly group [19]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the overall health and clinical status is likely to regulate albumin levels in addition to age.

Suggested factors leading to hypoalbuminemia in elderly, in CKD patients and in both, elderly with CKD.

As is well known, longitudinal studies on dialysis patients revealed a strong and inverse association between the serum albumin concentration and the risk of subsequent morbidity and mortality [76]. These findings indicate that serum albumin is an important prognostic indicator, although a unique sample of serum albumin has low sensitivity and specificity for the assessment of nutritional status. Of interest is the serum albumin change over time. In a study including elderly patients on CHD aged 75 years and older it was shown that a decrease or increase of 0.1 g/dL in serum albumin over 1 year was associated with poor survival, when compared with patients whose serum albumin had not changed over 1 year and had baseline values above 3.8 g/dL. Although this was an observational study, it can be used to encourage nephrologists to stabilize serum albumin above 3.8 g/dL in the elderly [77].

Like serum albumin, prealbumin (or transthyretin) has been used to predict poor outcomes in dialyzed patients. Although, little is known about the use of this marker in elderly patients on dialysis, Mittman et al. [78] in a 10-year prognostic study showed that advancing age was associated with lower prealbumin, whereas high levels of others chemical markers (albumin, creatinine, cholesterol, predialysis blood urea nitrogen) was positively associated with prealbumin. Moreover, low prealbumin concentration (<30 mg/dL) was associated with lower 10 year cumulative survival in CHD and PD patients and for each 1 mg/dL increase in serum prealbumin a 9% and 5% higher survival rate was observed in CHD and PD patients, respectively [78].

CONCLUSION

The growing number of elderly individuals starting dialysis makes it urgent to develop clinical practice guidelines for multicomorbidity elders, such as those under dialysis. Since the most important organizations that develop guidelines toward the health care of CKD patients have not worked on a guideline focusing on the elderly, this review addressed the tools of nutrition assessment directed to aged patients on dialysis.

The nutritional assessment of elderly individuals on dialysis requires attention to aspects related to aging, as the misdiagnosis of PEW in this subset of patients is likely to predispose to sarcopenia, frailty, worse quality of life and higher mortality rates. The development of protocols directed to elderly patients on dialysis including methods that enable the assessment of nutritional status should be developed and tested in clinical practice to assess the response to nutritional interventions. Until a systematic approach to identifying elderly patients on dialysis with PEW is available, it is prudent to use the nutritional assessment tools such as SGA or MIS to diagnose for PEW and complement them with objective measurements, such as calf circumference and ideally body composition assessment, and using knee height as the estimate of true height to apply in equations.

The investigation of specific aspects related to aging listed in Table 3 should be incorporated in the practice of dietitians dealing with this subset of patients. Routine assessment with periodicity varying from 3 to 6 months is advisable to plan for early intervention and to monitor nutritional changes over time. In addition, it is important to test whether the methods and cutoffs commonly applied in adult patients on dialysis are valid in elderly patients. As this segment of the population is growing, research is necessary to improve the screening and assessment of PEW, as well as to prospectively follow the nutritional status of elderly patients on dialysis.

FUNDING

J.R. is supported with grants from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Comments