-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Masako Hayashibara, Hiroshi Hagino, Ikuta Hayashi, Keita Nagira, Yuta Takasu, Daichi Mukunoki, Hideki Nagashima, A case of septic arthritis of the elbow joint in rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed by arthroscopic synovectomy, Modern Rheumatology Case Reports, Volume 7, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 24–27, https://doi.org/10.1093/mrcr/rxac048

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

We report a case of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) septic arthritis of the elbow detected by arthroscopic synovectomy in an 81-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who was initially diagnosed with a rheumatoid arthritis flare-up. The patient was administered abatacept, an antirheumatic biological agent, as the synovial fluid culture was negative. Destruction of the joint progressed despite medication, and the patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy. MRSA was detected in the culture of the synovium that was collected intraoperatively, and septic arthritis was diagnosed. The infection subsided with anti-MRSA antibiotics, but the patient continued to experience moderate pain and limited motion. In RA patients, it might be difficult to differentiate minor findings from infection. Arthroscopic synovectomy is one of the selectable procedures that should be actively considered when infection is suspected.

Introduction

Septic arthritis (SA) affects 12 in 100,000 people per year, and SA of the elbow is rare, accounting for 6–9% of cases [1–3]. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a risk factor for SA, including immunosuppressive therapy and joint deformities [4–7]. Because RA itself is an inflammatory disease, it can be difficult to differentiate from infection [8, 9]. We report a case of SA of the elbow in an RA patient who experienced progressive joint destruction because of a delay in diagnosis arising from the difficulty in differentiating between infection and RA flare-up.

Case presentation

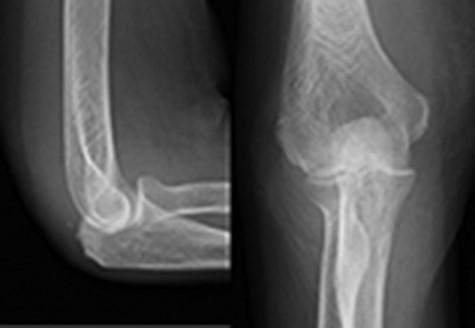

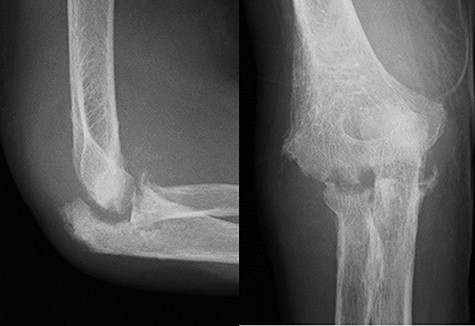

An 81-year-old woman was treated for RA over 4 years; her disease was controlled with 200 mg of bucillamine per day and 1 mg of betamethasone per day, and the disease activity was low. Six milligrams of methotrexate per week was added 2 years ago because of poor disease control; however, it was discontinued due to side effects. The patient was previously treated for exertional angina pectoris and chronic heart failure. The patient presented with a 2-month history of worsening joint pain and swelling in her right elbow. Blood tests showed9000/mm3 level of white blood cell (WBC) count, 96.0 mg/l level of C-reactive protein (CRP), and 338 ng/ml level of matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3). The previous physician had reported that the aspirated joint fluid from the right elbow was slightly cloudy and the culture was negative. Because the previous therapy was ineffective, she was referred to our department. A clinical examination showed localised warmth, slight erythema, and tenderness over the elbow as well as slight swelling of the right wrist. The range of motion of her right elbow was severely restricted to 50°−110° and 30°−60° of rotation with crepitus and pain; the wrist motion was not restricted. An X-ray examination revealed a joint space narrowing of Larsen grade II (Figure 1). The blood tests were as follows: WBC count, 10,300/mm3 (78% neutrophils); CRP, 65.7 mg/l; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), 92 mm/h; MMP-3, 155 ng/ml; rheumatoid factor, 10.4 IU/ml; and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, 19.4 U/ml. The Disease Activity Score-28 for Rheumatoid Arthritis with Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (DAS 28-ESR) was 5.68 with high activity, and the Health Assessment Questionnaire score was 1.625. Infection was suspected; however, the culture of the aspirated fluid of the right elbow was negative again. The CRP level decreased to 7.5 mg/l 4 weeks later, and abatacept (ABT) was added to the patient’s treatment for a suspected RA flare-up. Two months later, the patient complained of an elbow pain flare-up. The laboratory data at this time were as follows: WBC count, 6400/mm3; CRP, 17.4 mg/l; ESR, 46 mm/h; MMP-3, 87 ng/ml; and procalcitonin level, 0.04 ng/ml. The movement of the elbow was more restricted. X-ray examination showed progressive joint destruction (Figure 2), and magnetic resonance imaging showed joint effusion, bone marrow oedema, and synovial hyperplasia (Figure 3). The small amount of aspirated fluid was bloody, and the synovial fluid culture was negative once again. ABT administration was discontinued. The patient underwent arthroscopic debridement and synovectomy under general anaesthesia for the diagnosis and treatment of suspected infection. During the procedure, no intra-articular pus accumulation was detected; however, generalised villous synovial growth (Figure 4) and joint destruction were observed. Although the synovial fluid culture was negative, the culture of the synovial tissue collected during the synovectomy produced methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with SA.

X-ray revealed a joint space narrowing of Larsen grade II at initial visit.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed joint effusion, bone marrow oedema, and synovial hyperplasia at white arrow.

Arthroscopic findings showed generalised villous growth in her right elbow.

The patient was treated with linezolid, an anti-MRSA drug, for 5 days post-surgery. The treatment was then switched to daptomycin due to renal dysfunction. Ten days later, she administered ceftriaxone sodium for 6 days due to a urinary tract infection. It was switched from daptomycin to 250 mg per day of levofloxacin with oral intake 3 weeks after surgery, since CRP improved to 2.0 mg/l and was continued until 3 months. 6 weeks post operatively systemic arthritis appeared and CRP level increased to 50 mg/l, although both clinical and laboratory findings improved her right elbow. We diagnosed an RA flare-up, and 10 mg per day of corticosteroid was administered. Since laboratory data subsequently improved, the dose of corticosteroid was decreased to 5 mg per day and there was no recurrence of infection. Two years after synovectomy, the patient reported moderate pain of 45 mm per 100 mm on the visual analogue scale and a restricted motion to 50°−110° and 30°−60° of rotation. The patient had residual functional impairment, Disease Activity Score-28 was 3.45 with moderate activity, and Health Assessment Questionnaire score was 2.0. The patient declined to undergo functional reconstruction.

Discussion

Bacterial SA is a serious health issue that is associated with considerable morbidity [2, 5, 10]. SA of the elbow is rare in adults, as compared with SA of the knee, hip, or shoulder joint [1–3]. According to a previous study, the risk factors for SA were RA, osteoarthritis, joint prosthesis, low socioeconomic status, intravenous drug abuse, alcoholism, diabetes, previous intra-articular corticosteroid injection, and cutaneous ulcers [4, 5, 11]. SA is also associated with a compromised immune system comorbidity and previous joint disease (osteoarthritis and RA, among others) [2, 10, 12–16]. The chronic synovitis and the abnormal joint structure that are characteristic of RA provide favourable conditions for bacterial survival and growth [11]. Kaandrop [4] showed that skin infection is an important risk factor for SA and that all patients with SA caused by skin infections had RA. Morris [16] reported that the risk of SA may be high in patients with RA because skin integrity is compromised because of deformations, nodules, and medication-induced atrophy. In this case, mild joint destruction of the right elbow was observed at the onset of symptoms, and corticosteroids and a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) were administered over a long period.

Typically, SA has an acute onset with severe joint pain, accompanied by swelling and erythema at the affected joint and systemic manifestations of infection, including fever and elevated WBC count, CRP, and ESR. However, a previous study reported normal body temperature and WBC count in 29% and 30% of patients with SA, respectively. Thus, these measurements alone are unreliable for diagnosis [17]. Moon [18] demonstrated subtle findings and inconclusive laboratory results in some patients. In patients with RA, the onset of SA can be more insidious and is often mistaken for an RA flare-up. Furthermore, the presentation may be more subtle in patients taking immunosuppressants (glucocorticoids, DMARDs, and biologics) [19]. Positive synovial fluid cultures have been previously reported in 82–95% of patients with SA of the shoulder and elbow [20]. The efficacy of blood cell counts in joint fluid (i.e. WBCs > 50,000 /mm3 and neutrophil counts > 90%) for differentiating SA has also been reported [17]. However, RA is an inflammatory disease and is thus difficult to differentiate from SA based on the characteristics of joint fluid [20].

The first step in treating monoarthritis is to determine the presence of acute inflammation based on blood data and the culture and characteristics of joint fluid. Infection is diagnosed if blood or joint fluid cultures are positive [21]. If the inflammatory reaction is mild and it is challenging to differentiate between RA and other joint diseases based on the joint fluid characteristics alone, joint fluid culture must be used as a reference for diagnosis. In this case, the initial diagnosis was an RA flare-up because joint fluid cultures were negative at both the time of examination by the previous doctor and the time of referral to our clinic.

Laboratory findings and symptoms of SA are less severe in patients with RA compared with those of non-RA patients, and the cell counts in the joint fluid are lower in patients with RA compared with non-RA patients [4, 19]. Further, Ampula had noted that symptoms may be less severe in patients on immunosuppressive drugs.

Additionally, because staphylococci form biofilms, mild cases with a subacute or chronic course may have less bacterial leakage into the joint fluid, leading to negative cultures. We mistook the condition of the patient for an RA flare-up because of mild elevations in WBC and CRP levels, the lack of fever, and repeated negative aspirated fluid cultures.

ABT has robust anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, which can pose a risk of infection [22, 23]. The pain worsening after ABT administration in this patient might associate that the infection was caused by ABT administration. However, the elbow pain worsened 1 month after ABT administration, the progression of joint destruction 1 month later was very strong, and no changes in the characteristics of the arthrocentesis fluid were observed before and after ABT administration. Therefore, it was concluded that the infection had occurred before the administration of ABT.

Although both T-helper (Th) cells (CD4+ T cells) and cytotoxic T cells (CD8+ T cells) are found in inflamed synovium, CD4+ T cells are much more abundant. Furthermore, CD4+ cell depletion significantly ameliorates the course of SA in mice, whereas CD8+ T cell depletion does not affect the course of SA compared with control mice [24]. CD4+ T cells likely contribute to the pathogenesis of S. aureus SA because they produce proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-α and interferon-gamma via activated macrophages [24]. ABT is a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4-Ig that inhibits the full activation of T cells and may cause CD4+ T cell depletion. In this case, ABT may have temporarily decreased the inflammatory response.

Arthroscopic procedures have recently come into favour for the treatment of various elbow disorders [25–27]. The advantages of arthroscopic procedures compared with open techniques include a more thorough inspection of the elbow joint, minimal morbidity, and a shorter rehabilitation time. However, the disadvantage of arthroscopic procedures is nerve injuries, as an inflamed synovium, thin fragile capsule, and diffuse synovitis alter the nerve anatomy [27, 28]. Although aspirated fluid cultures are negative, synovial tissue cultures taken intraoperatively may be positive. Moon et al. reported positive cultures of intraoperative tissue samples in 7 of 10 cases [18]. In our case, the intraoperative synovium samples obtained during the arthroscopic procedure were positive for MRSA, and the diagnosis of SA was confirmed. Arthroscopic debridement of infected tissue may be insufficient when joint destruction has occurred. However, arthroscopic debridement is minimally invasive, and it is an option for diagnosis and treatment when the diagnosis is uncertain. In this case, even if the joint fluid culture was negative at the time of initial diagnosis, synovial membrane sampling under arthroscopic synovectomy may have prevented the progression of joint destruction.

We report a case of SA of the elbow in a patient with RA. The diagnosis and treatment were delayed because an RA flare-up was initially misdiagnosed. In systemic joint diseases such as RA, SA should be considered when inflammation is detected in a single joint, even if clinical findings are subtle. Arthroscopic debridement is a minimally invasive procedure, which can be used for both diagnosis and treatment, even if the diagnosis is not confirmed.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient consent

The patient and her family provided written informed consent for publication of her data.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.