-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tsuyoshi Shirai, Jun Suzuki, Shimpei Kuniyoshi, Yuito Tanno, Hiroshi Fujii, Granulomatosis with polyangiitis following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination, Modern Rheumatology Case Reports, Volume 7, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 127–129, https://doi.org/10.1093/mrcr/rxac016

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

We report the first case of proteinase 3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) with predominant ears, nose, and throat manifestations following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination. A 63-year-old woman presented with aural fullness 3 days after vaccination. She presented with progressive rhinosinusitis and otitis media leading to profound hearing loss within 3 weeks. Clinical imaging revealed soft-tissue shadows in the paranasal sinuses with multiple pulmonary nodules, and histopathology was consistent with a diagnosis of GPA. It is crucial to be wary of the possibility of GPA in patients who received COVID-19 vaccines due to its rapid disease progression.

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has significantly influenced our lives. Vaccination is one of the cornerstones critical to control COVID-19. The safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines have been globally accepted. However, cases of autoimmune diseases including giant cell arteritis following COVID-19 vaccination have been described [1, 2]. Among antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAVs), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) presents with characteristic symptoms in the ears, nose, and throat (ENT). To the best of our knowledge, only two cases of AAV following COVID-19 vaccination have been described, presenting with necrotising glomerulonephritis [3, 4]. Here, we report the first case of proteinase 3 (PR3)-ANCA-positive GPA with predominant ENT manifestations following COVID-19 vaccination (Pfizer-BioNTech).

Case report

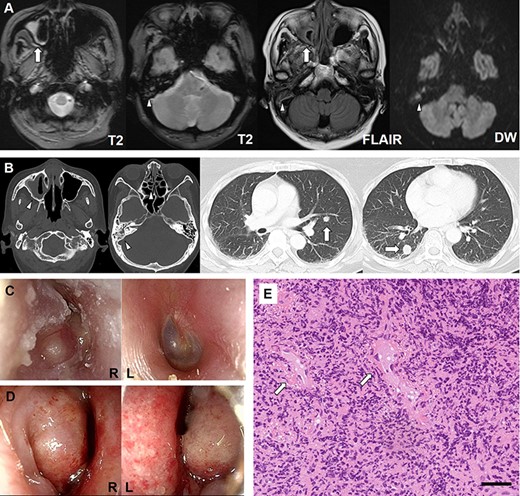

An otherwise healthy 63-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for severe vertigo and hearing loss 22 days after receiving the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. She underwent a medical checkup 3 months ago, and her chest X-ray was normal at that time. Three days after vaccination, she presented with mild fever, right aural fullness, and bilateral nasal congestion. She was diagnosed with rhinosinusitis and otitis media. However, treatment with antibiotics for 2 weeks did not improve her condition. On the day of admission, she experienced severe vertigo and headache, which prompted consult to the previous hospital. Magnetic resonance imaging showed oedematous thickening of the maxillary sinus and mastoid cells (Figure 1(a)). Computed tomography (CT) revealed soft-tissue shadows in the paranasal sinuses with multiple pulmonary nodules (Figure 1(b)), consistent with the previous diagnosis of right otitis media, mastoiditis, and maxillary sinusitis. However, based on these findings, GPA was suspected, which prompted a referral to our hospital for further evaluation. On admission, the patient was conscious with a slightly elevated body temperature (37.1°C). Otolaryngologic examination revealed unidirectional horizontal spontaneous nystagmus to the left and bulging tympanic membrane with purulent effusion in the right ear (Figure 1(c)). Rhinoscopy showed bilateral nasal mucosal swelling and erosion (Figure 1(d)). Pulmonary examination was unremarkable.

Imaging, clinical, and histopathologic findings. (a) Magnetic resonance imaging shows oedematous thickening of the maxillary sinus (arrows) and mastoid cells (arrowheads). (b) Computed tomography reveals soft-tissue shadows in the paranasal sinuses (arrowheads) and multiple nodules in the lungs (arrows). (c) Otoscopy demonstrates a bulging tympanic membrane with purulent effusion in the right ear. (d) Rhinoscopy shows swelling and erosion of the bilateral nasal mucosa. (e). Histopathologic examination of the nasal mucosa reveals vascular fibrin deposition (arrows) and granulation tissue with intensive infiltration of inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils. Black bar indicates 50 μm.

Blood tests showed elevated white cell count (12,800 cells/µl). Laboratory examinations revealed increased C-reactive protein levels (14.32 mg/dl) and normal renal function. Urinalysis was unremarkable. Serologic tests demonstrated elevated PR3-ANCA levels (259 U/ml; normal, <3.5 U/ml) with negative myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA. Pure tone audiometry revealed right profound hearing loss with bone conduction threshold deterioration. Histopathologic examination of the nasal mucosa revealed fibrin deposition in the small vessels and granulation tissue with intensive infiltration of inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils (Figure 1(e)). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of GPA. Although evaluations for lung nodules were planned, vertigo worsened severely the day after admission, with high fever and elevation of inflammatory markers, which prompted us to initiate immunosuppression. Because of concerns of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection after the use of rituximab, she was treated with prednisolone (60 mg/day) and intravenous cyclophosphamide (500 mg), which improved her conditions. The follow-up CT revealed regression of lung nodules, supporting the idea that they were inflammatory in nature.

Discussion

Six cases of AAV following COVID-19 have been described previously [5]. All patients were diagnosed with necrotising glomerulonephritis, and the positivity for MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA was half and half. Moreover, two cases of AAV after COVID-19 vaccination have been reported, presenting with glomerulonephritis. The first patient experienced PR3-ANCA-positive glomerulonephritis following inoculation with Moderna vaccine [3]. In contrast, the second case was diagnosed with MPO-ANCA-positive crescentic necrotising glomerulonephritis after Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination [4]. Cases of AAV have also been reported following influenza vaccinations [6]. Although drug-induced AAV is usually associated with MPO-ANCA, no predilection for ANCA type exists in AAV associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination.

Unlike other cases, our patient presented with progressive rhinosinusitis and otitis media leading to profound hearing loss within 3 weeks. The presence of hearing loss with bone conduction threshold deterioration and vertigo with unidirectional spontaneous nystagmus suggested severe inner ear damage. Moreover, the presence of pulmonary nodules indicated the systemic progression of GPA. Although PR3-ANCA-positive GPA is less common in Japan, this study described a case of PR3-ANCA-positive GPA 3 days after COVID-19 vaccination (Pfizer-BioNTech) in a Japanese patient presenting with typical upper and lower respiratory manifestations. Although it is difficult to demonstrate a causal relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and GPA, it is crucial to be wary of the possibility of GPA in patients who received COVID-19 vaccines due to its rapid disease progression. It is not certain whether spontaneous improvement could be expected in AAVs following vaccination, and appropriate treatments should be performed without delay.

Development of AAVs has been observed after both SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination [3–5]. This evidence suggests that the immune response against SARS-CoV-2, messenger RNA vaccines, and adjuvants could trigger the onset of AAVs, especially in individuals that have a predisposition to AAVs. Since it is possible that patients who developed AAVs following COVID-19 vaccination are also at high risk for developing AAVs following SARS-CoV-2 infection, the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination would outweigh the risks in the era of the pandemic. On the other hand, re-administration of a vaccine should be carefully considered in such cases. This study highlights the importance of evaluating patients for ENT symptoms after COVID-19 vaccination.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Department of Hematology & Rheumatology, Tohoku University, for their helpful inputs.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: 21K08469) for T.S.

Patient consent

Written informed consent for the publication of this case report was obtained from the patient.

Ethical approval

This work was approved by Ethics committee of the Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number 23185).