-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thane A Militz, Lawrence Scheele, Richard D Braley, An observation confirming the geographic distribution of Noah’s giant clam Tridacna noae includes the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, Journal of Molluscan Studies, Volume 91, Issue 2, June 2025, eyaf011, https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eyaf011

Close - Share Icon Share

The known diversity of giant clams (Bivalvia: Tridacninae) has expanded considerably in recent years with descriptions of new species and resurrection of previously synonymized names. Among the recent taxonomic changes, resurrection of Tridacna noae (Röding, 1798) as a valid species distinct from T. maxima (Röding, 1798) has been of widespread significance (Su et al., 2014). Past inadvertent confusion between these two taxa meant that prior population assessments and demographic parameters for giant clams were possibly erroneous in areas of sympatry (Borsa et al., 2015). To effectively assess population trends for these iconic and ecologically significant taxa, an accurate understanding about the geographic distribution of T. noae has become critical (Neo & Li, 2024).

Since the resurrection of T. noae, observations of this taxon have been made across the Indo-Pacific region (Fig. 1). The presumed geographic distribution of T. noae now ranges from the Ryukyus Archipelago to Kiritimati in the north and from Western Australia to the Cook Islands in the south, extending westwards into the South China Sea and East Indian Ocean at lower latitudes (Morejohn et al., 2023). Within this range, however, several areas known to host giant clams have yet to report T. noae as present. Perhaps most conspicuous has been an absence of observations from the east coast of Australia where the world’s most extensive coral reef system, the Great Barrier Reef, covers a vast area (c. 348,000 km2) within the distributional limits of this species.

Presumed geographic distribution of Tridacna noae is indicated by the shaded polygon. Circles indicating visual observations and triangles indicating genetically validated observations are redrawn from Morejohn et al. (2023). Our visual observation of T. noae from the Great Barrier Reef of Australia is indicated in red. Inset shows the location of this observation within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park at Alma Bay (MNP-19-1093), Magnetic Island.

Designated a World Heritage Area, most (c. 99%) of the Great Barrier Reef is today managed as the multiuse Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP), which recognizes giant clams as protected species in need of special management provisions (for further information, see the Great Barrier Reef Park Regulations 1983, compilation no. 53). Knowledge pertaining to giant clams within the GBRMP, however, largely derives from studies completed when T. noae was still synonymized with T. maxima. These studies recognized six species of giant clams within the GBRMP, including Hippopus hippopus (Linnaeus, 1758); T. crocea Lamarck, 1819; T. derasa (Röding, 1798); T. gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); T. maxima; and T. squamosa Lamarck, 1819 (Lucas, 1994). Discovery of an additional species, such as T. noae, would signal that a review of past research on giant clams within the GBRMP is necessary to ensure that current management provisions remain appropriate for their conservation.

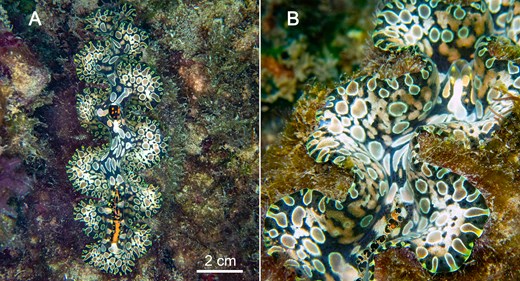

Here, we report on a recent in situ observation of T. noae at Alma Bay (MNP-19-1093), Magnetic Island, that now confirms the geographic distribution of this species includes the Great Barrier Reef of Australia (Fig. 1). Observation of an individual occurred opportunistically in January 2024 while compiling a field guide to the marine life of Magnetic Island (Scheele, 2025). The clam was sighted at a depth of 3.2 m with its siphonal mantle exposed and ventral hinge anchored in a reef flat composed of hard substrates covered in epilithic algal matrix and 20–50% live coral coverage. Phenotypically, this clam was typical of T. noae seen in neighbouring populations to the north, in Papua New Guinea (Militz, Kinch & Southgate, 2015), and the east, in New Caledonia (Borsa et al., 2015). Siphonal mantle morphology showed sparse and discontinuous eyes along its edge, and several layers of ocellate spots with a thin, white margin (Fig. 2). While not all T. noae exhibit these traits (Johnson et al., 2016), molecular analyses corroborate that these traits remain diagnostic of T. noae when present (Su et al., 2014; Borsa et al., 2015; Marra-Biggs et al., 2022; Morejohn et al., 2023).

Photographs of Tridacna noae within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park at Alma Bay (MNP-19-1093), Magnetic Island, taken in January 2024. A. Dorsal view of siphonal mantle. B. Close-up of siphonal mantle reveals traits used to identify this species in situ: sparsely arranged eyes and several layers of ocellate spots with a thin, white margin. Image credit: L. Scheele.

Discovery of T. noae at Alma Bay, Magnetic Island, affirms that a review of past population assessments and demographic parameters for giant clams within the GBRMP is now required. The high prevalence of T. noae in neighbouring populations (Borsa et al., 2015; Militz et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2016), and elsewhere where surveys have been carried out (e.g. Neo et al., 2018), highlights the possibility that past research on giant clams within the GBRMP might have been compromised due to inadvertent taxonomic confusion. Considering the life history of giant clams (Lucas, 1994), it seems unlikely that this species would be restricted to Magnetic Island, and a contiguous distribution along the east coast of Australia is anticipated. Since surveys for T. noae within the GBRMP have yet to occur (Braley, 2023), confirmation that the geographic distribution of this species includes the Great Barrier Reef is a much-needed first step towards ensuring inclusion of T. noae in future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Professor Paul C. Southgate and Dr Nittya S.M. Simard for support in the preparation of this article. Photographs of Tridacna noae within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park at Alma Bay (MNP-19-1093), Magnetic Island, were taken in compliance with the Reef Authority’s Photography, Filming and Sound Recording Activity Assessment Guidelines (document no. 100432) and relevant legislation.

FUNDING

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.