-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Francesco Biolzi, Ryan Dinnen, Bonamico Jacobs, Tyler Doty, Colleen Barkley, Keith Lynn Jackson, K Aaron Shaw, The Subcapital Femoral Neck Stress Fracture: A Novel Subtype of Compression-sided Stress Fracture—A Report of Three Cases, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages e2819–e2822, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usac304

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Femoral neck stress fractures (FNSFs) are increasingly common, particularly in military training. The usual mode of classifying these injuries is based on the involvement of the compression or tension side of the femoral neck; however, this may oversimplify and fail to address factors such as the orientation of the fracture line. We present a novel subtype of a compression-sided FNSF affecting the subcapital femoral neck and report the treatment outcomes in a military trainee population. A retrospective analysis of patients with a subcapital, compression-sided FNSF was identified from a single U.S. Army basic trainee installation. Radiographic evaluation as well as treatment outcomes associated with the ability to complete military training were reported. A total of three patients with a subcapital compression-sided FNSF were identified in a military trainee population, accounting for 10% of all FNSFs that developed over a 3-month period. Of these individuals, one was treated operatively while the other two were treated non-operatively. Overall, one patient was able to return to and successfully complete military training.

INTRODUCTION

Military trainees and high-impact athletes are populations at particular risk for femoral neck stress fracture (FNSF).1–5 Knapik et al.6 identified the incidence of FNSF in military trainees at 19/1,000 males and 80/1,000 females. Current treatment recommendations for compression-sided FNSF, classically characterized by an oblique fracture line extending from the inferior cortex, focus on the extent of fracture involvement based on the percentage of the femoral neck width.7

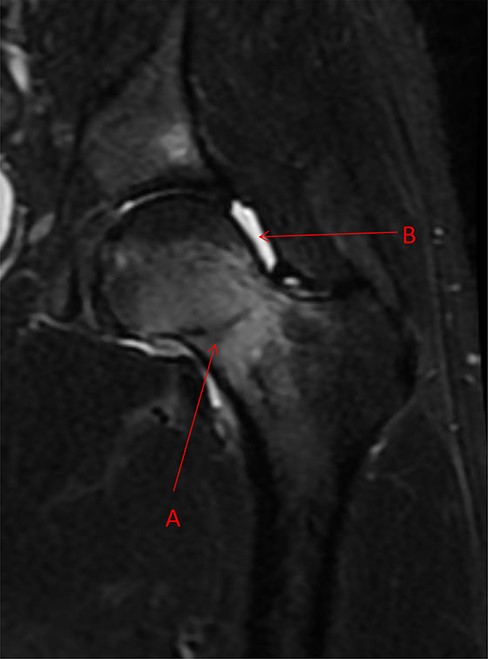

We have recently identified a unique subtype of compression-sided FNSF occurring in the subcapital region that propagates in a horizontal orientation (Fig. 1) in Army trainees. The unique characteristics of these fractures have implications on service members’ (SMs) treatment and return to duty, and to the authors’ knowledge, they have not been previously reported. The purpose of this study is to review cases of this subcapital FNSF treated over a 3-month period at a basic combat training (BCT) installation.

Coronal STIR magnetic resonance imaging image demonstrating femoral neck stress fracture beginning at the subcapital region of femoral neck at the femoral head and neck junction and propagating in a horizontal orientation toward the superior femoral neck (Arrow A). There is an associated hip effusion present (Arrow B).

To qualify terminology, U.S. Army Medical Command (MEDCOM)’s Bone stress injury (BSI) policy (as of 2018) stated that “bone stress injury,” BSI, or “stress reaction” may be used interchangeably for lower grade (grades 1–3) BSI; whereas “stress fracture” may be used interchangeably for grade 4 BSI.

METHODS

This project was deemed exempt from institutional review board review. A retrospective review of FNSF sustained at a single BCT installation was conducted between June 1, 2019, and August 31, 2019. Thirty-one femoral neck stress injuries (FNSI) requiring cessation of training were identified with three characterized as subcapital FNSFs.

All trainees participated in a structured physical therapy (PT) protocol including weight-bearing modification, removal from military training, and gradual progression of strengthening/gait training as their pain resolved. Return to training was allowed when there was painless weight-bearing (including running and jumping), symmetric functional movement, and the ability to perform all components of military training activities without dysfunction.

Case 1

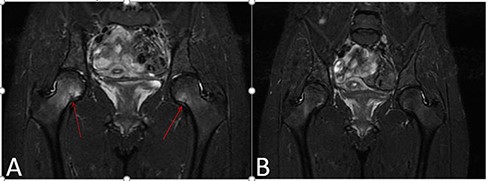

A 19-year-old female SM in week 7 of BCT presented with a 5-day history of progressive bilateral hip pain. She had no traumatic history and reportedly did not exercise regularly prior to BCT. Her pain was aggravated with weight-bearing and relieved with rest. Radiographs were negative for a fracture, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated bilateral subcapital FNSFs, with fracture lines involving 30% on the right and 25% on the left (Fig. 2A). Given the fracture extent, she was indicated for non-operative management, provided crutches, and allowed to weight bear as tolerated.

Case 1. (A) Coronal Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) magnetic resonance imaging sequence of bilateral hips demonstrating a bilateral subcapital femoral neck stress fracture involving approximately 30% of the femoral neck width on the right and 25% on the left. (B) Follow-up coronal STIR magnetic resonance imaging sequence obtained 4 weeks later after a period of activity modification, demonstrating healing of the aforementioned femoral neck stress fractures.

Five weeks after the initial MRI, a follow-up MRI demonstrated healing of her FNSFs, decreasing to 10% bilaterally (Fig. 2B). Her pain had resolved, and she progressed to full weight-bearing with limited physical activity. Two months following her initial presentation, she remained pain-free but had elected to undergo discharge from the Army.

Case 2

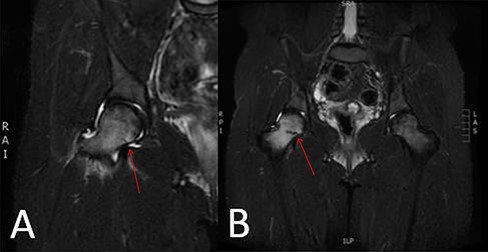

A 18-year-old female SM in week 3 of BCT presented with a 3-day history of severe right hip pain that began during a run. She reported that pain worsened with ambulation and lessened with rest. She demonstrated pain with hip range of motion, particularly with abduction and external rotation. She was provided crutches and counseled to weight bear as tolerated while refraining from impact activities. A bone scan was obtained prior to MRI because access to MRI imaging was not available within 24 hours and demonstrated focal uptake at the subcapital region of the right femoral neck. Subsequent MRI demonstrated a subcapital FNSF involving 26% of the femoral neck with an associated hip effusion (Fig. 3A). Given the fracture extent, she continued on non-operative management.

Case 2. (A) Initial coronal STIR magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating focal bone marrow edema in the right subcapital femoral neck region with a compression-sided fracture line extending approximately 26% across the femoral neck with an associated hip effusion. (B) Coronal STIR magnetic resonance imaging sequence obtained 9 days later due to the presence of initial hip effusion, demonstrating progression of the femoral neck stress fracture involving approximately 66.7% of the right femoral neck width with increased surrounding diffuse marrow edema.

Repeat MRI 2 weeks later demonstrated fracture progression to 66.7% of the femoral neck (Fig. 3B). Her pain had significantly decreased (Visual Analog Scale 2/10) with a resolution of pain with activities and was continued on non-surgical care. However, given the rapid onset of her fracture early in BCT, in combination with her fracture progression, she was recommended for a medical discharge from the Army. At her discharge appointment, she continued to report 2–4/10 pain, primarily with prolonged standing, but had improved significantly overall.

Case 3

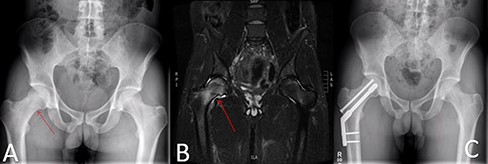

A 22-year-old male SM in week 4 of BCT presented for right hip pain for the previous week. He was sprinting and felt a pull in his groin, resulting in consistent hip pain. Physical activity exacerbated the pain and was only mildly relieved by rest. He was tender over the right groin and had limited right hip motion due to pain. Radiographs demonstrated a linear area of increased radio-density in the subcapital region of the femoral neck (Fig. 4A). He was then placed on crutches and an urgent MRI was obtained, showing a subcapital FNSF involving 84% of the femoral neck (Fig. 4B). Given the extent of the fracture line, surgical intervention was indicated, and the patient underwent stabilization with an integrated screw-plate construct and an independent, derotational screw (Fig. 4C). Postoperatively, the patient was restricted from weight-bearing to the right lower extremity.

Case 3. (A) Anterior/Posterior pelvis radiograph demonstrating an area of sclerosis of the right compression side of the femur in the subcapital region. (B) Coronal STIR magnetic resonance imaging image demonstrating a subcapital femoral neck stress fracture extending approximately 84% of the femoral neck width with an associated femoral neck effusion. (C) Postoperative image demonstrating dynamic hip screw.

After 30 days of convalescence, the patient initiated PT. Three months following surgery, he remained pain-free and physical activity was advanced. After successfully completing functional rehabilitation therapy, he returned to BCT 4 months following surgery, graduating from BCT 6 months following his surgery. After 1 year, he remained in active military service. His right hip remained asymptomatic, and he was tolerating military activity without pain/limitations.

DISCUSSION

Through a review of all FNSI experienced at a single installation, this atypical subcapital FNSF pattern accounted for approximately 10% of all FNSI. Of the three SMs treated, only one SM, treated operatively, was able to return to graduate from the BCT and remain in active military service. This specific pattern has not been previously described in the literature to the knowledge of the authors, despite accounting for a sizable proportion of our patient population, and has direct implications on injury evaluation and treatment.

Lower extremity bone stress injuries are relatively common in the U.S. Military, with 31,758 SMs’ experiencing one between 2009 and 2012.5 Of those, approximately 9% involved FNSF. FNSFs are of significant concern given the potential for progressing to a complete and/or displaced fracture without appropriate intervention. As such, rapid identification of FNSF is crucial to maintaining the functionality required for active military status.

There are two predominant subtypes of FNSF, tension, and compression-sided.8 Tension-sided FNSFs are considered high-risk injuries for fracture completion and possible displacement and are typically considered an indication for prophylactic stabilization. Conversely, compression-sided affects the inferior femoral neck and is considered more stable. Shin and Gillingham9 were the first to propose a classification system delineating compression-sided FNSF by the fracture extent defined as the fracture line relative to the maximal femoral neck width. In their institutional protocol, FNSFs involving >50% of the femoral neck width were characterized as high-risk injuries and treated with prophylactic stabilization.

Awareness of this unique subcapital FNSF is important for several reasons related to the location and orientation of the fracture. As demonstrated in the provided cases, these injuries originate from the subcapital region and traverse the femoral neck in a horizontal orientation compared to typical stress fractures involving the femoral neck. Previous studies have demonstrated that vertically oriented injuries of the femoral neck, or stress fractures classified as higher Pauwels grade injuries, are more likely to undergo subsequent displacement.10 This unique fracture orientation provided compressive forces across the stress fracture site and affected a location of primarily trabecular bone, both being beneficial components to fracture healing. Anecdotally, these have been noted to have a more favorable prognosis for successful non-surgical intervention, despite fracture lines surpassing the proposed 50% threshold value (case 2).

CONCLUSION

Through this case series, we identified a unique FNSF subtype involving the subcapital region. Given the unique, more horizontal orientation of the fracture, more accurate assessment of the fracture extent may not follow the typical measurement standard using the maximal femoral neck width and may require a modified measurement method. The more stable orientation of this fracture provides a favorable prognosis for non-surgical management; however, surgical intervention remains recommended for tension-sided fractures or compression-sided fractures spanning greater than 50% of the diameter of the femoral neck.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are no acknowledgements.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE

Not applicable.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

F.B.: lead author, data analysis, manuscript preparation, and submission POC.

B.J.: data analysis, references, and editor.

A.S.: study design, IRB approval, and editor.

K.L.J.: editor and data interpretation.

T.D.: case collection.

R.D.: case collection and manuscript preparation.

C.B.: access to PT protocols and data collection.

INSTITUTIONAL CLEARANCE

Institutional clearance approved or does not apply.

REFERENCES

Author notes

The views expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government, the DoD, or the Department of the Army.