-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Robert Dichiera, Duke Yim, Transient Osteoporosis of the Hip: A Case Report of a U.S. Soldier, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages e2816–e2818, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usac284

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Transient osteoporosis of the hip is described as an uncommon, self-limiting condition that typically affects middle-aged men and pregnant women in their third trimester. Transient osteoporosis most commonly affects the hip, but cases have been described in the knee, ankle, and foot. Symptoms include pain, limited range of motion, and antalgic gait. A greater level of awareness of transient osteoporosis of the hip as a differential diagnosis for hip pain will obviate unnecessary, inefficient, or unproductive interventions and treatments. Transient osteoporosis of the hip is a self-limiting disease process that requires only symptomatic treatment such as basic analgesia, physical therapy, and activity modification. On average, recovery is seen within 6-12 months.

INTRODUCTION

Transient osteoporosis of the hip (TOH) is described as an uncommon, self-limiting condition that typically affects middle-aged men and pregnant women in their third trimester. Transient osteoporosis most commonly affects the hip, but cases have been described in the knee, ankle, and foot. Symptoms include pain, limited range of motion (ROM), and antalgic gait, with expected complete resolution of symptoms after 6-12 months. The purpose of this case study is to bring awareness of TOH as a differential diagnosis of hip pain in a military population. To date, there has not been a case of TOH in a soldier described in the literature.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

A 47-year-old active duty male presented to the orthopedic clinic for the evaluation of his bilateral hip pain, left greater than right. The patient reported intermittent bilateral hip pain with no specific mechanism of injury or trauma. The patient stated that 3 months before this encounter he developed similar symptoms of left hip pain deep to the inguinal region that increased with all movements of the lower extremity, especially with lateral/abduction maneuvers. The pain radiated to the right hip and inguinal region and was described as 5/10 that increased to 9/10 with lateral/abduction maneuvers, especially while seated. There had been minimal resolution of symptoms over the last 2 months. He reported that “being still” transiently alleviated the pain.

Before this encounter, he had been evaluated by his primary care provider, as well as general surgery clinic, who ruled out inguinal hernia as the cause of significant inguinal pain. The patient was placed on crutches in a non-weight-bearing status on the left lower extremity. He was prescribed morphine extended release twice a day as needed for pain as well as Percocet for breakthrough pain by his primary care provider. He had no history of rheumatoid arthritis, human immunodeficiency virus, cancer, alcoholism, or illicit drug use. Past medical history, past surgical history, family history, and social history were non-contributory. He reported that he was a social alcohol drinker and a social cigar smoker.

The patient’s interview was notable for his inability to relax or get into a comfortable position because of significant bilateral hip pain. Examination of the lower extremities was limited secondary to bilateral hip pain with no neurologic deficits. Pertinent findings were pain with log roll and Stinchfield testing. The ROM was limited secondary to pain.

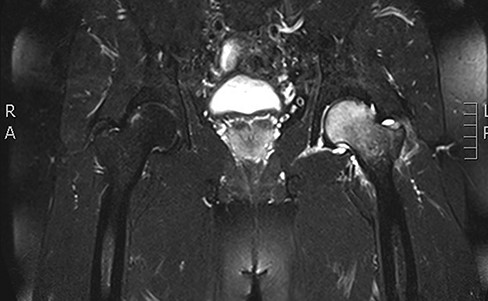

X-ray of the pelvis and hips demonstrated no acute fractures, dislocations, or evidence of avascular necrosis. Previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bilateral hips demonstrated no ligamentous or labral pathology bilaterally. There was evidence of significant bone marrow edema in the femoral heads, left greater than right, with no evidence of osteonecrosis (Fig. 1).

Coronal T2 sequence demonstrating significant bone marrow edema of the left femoral head with evidence of bone.

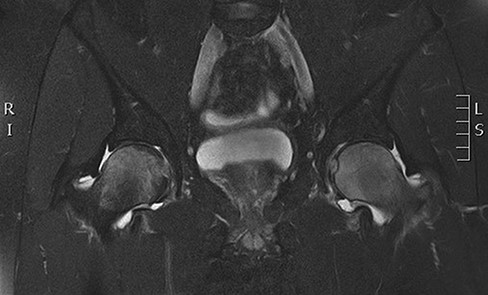

MRI of the bilateral hips obtained during this encounter again demonstrated no evidence of ligamentous or labral pathology bilaterally. A comparison of the MRI from 1 month earlier demonstrated resolving bone marrow edema of the left femoral head and neck, but interval increased bone marrow edema of the right femoral head consistent with the patient’s subjective symptomology. And again, no evidence is suggestive of avascular necrosis (Fig. 2). The encounter concluded with treatment recommendations of activity modification (i.e., physical profile), physical therapy referral for basic ROM and strengthening rehabilitation, continued crutch use for symptom relief, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The patient was encouraged to discontinue the narcotics previously prescribed by his primary care provider.

Coronal T2 sequence demonstrating bone marrow edema of the left femoral head with evidence of worsening bone.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At the 2-month follow-up (approximately 5 months from the start of symptoms), the patient reported improving hip pain with occasional crutch use. He reported intermittent pain of the bilateral hips which he now quantified as 1/10 with aggravating activities such as walking long distances or standing long periods. Otherwise, his pain had decreased significantly and he had not required routine narcotics for pain relief as his symptoms were managed with naproxen.

The physical exam demonstrated improvement in active ROM. The patient did endorse minimal pain with log roll and Stinchfield examination bilaterally. Gait was non-antalgic.

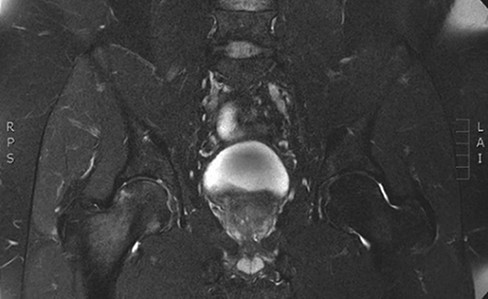

X-ray of the pelvis demonstrated an increase in osseous mineralization of the left femoral head and neck compared to previous films. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated near complete resolution of bone marrow edema of the left proximal femoral head with the overall improvement of the right femoral head marrow edema. There was interval worsening of marrow edema of the right femoral neck (Fig. 3).

Coronal T2 sequence demonstrating near complete resolution of bone marrow edema of the left proximal femoral head.

At approximately the 6-month follow-up (9 months from the start of symptoms), the patient was pain-free with only one occasion of hip pain since the last orthopedic clinic visit. Physical exam demonstrated continued improvement to include reduced symptoms with hip and active ROM.

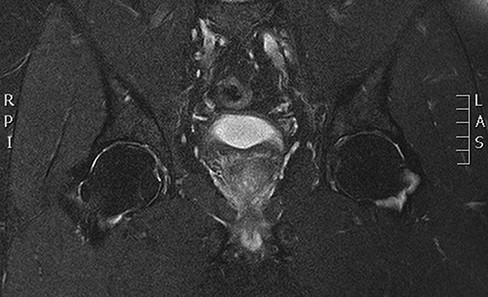

MRI of the bilateral hips obtained demonstrated interval resolution of previously seen bilateral femoral head and neck bone marrow edema. Normal bone marrow signals were now present bilaterally (Fig. 4).

Coronal T2 sequence of the bilateral hips approximately 9 months Status post initial complaint demonstrating interval resolution of previously seen bilateral femoral head and neck bone marrow edema.

DISCUSSION

Transient osteoporosis of the hip is described as an uncommon, self-limiting condition that typically affects middle-aged men and pregnant women in their third trimester.1–3 The condition was first described by Dr. Curtiss and Kincaid in 1959.1 Transient osteoporosis most commonly affects the hip, but cases have been described in the knee, ankle, and foot.4 Symptoms include pain, limited ROM, and antalgic gait. Although TOH is described as uncommon, an increasing number of case reports regarding TOH are available. A search utilizing PubMed resulted in nearly 400 articles, including close to 200 case reports.

The etiology of TOH remains elusive. Several theories exist to include compression of the obturator nerve, reflex sympathetic dystrophy/complex regional pain syndrome, viral infection, and deficiencies in bone metabolism such as Vitamin D.2,4–6 Hip pain has a very broad differential to include femoral acetabular impingement syndrome, labral pathology, stress and insufficiency fractures, infective and inflammatory arthritis, and avascular necrosis as seen in military recruits.7,11–13 A good history and focused physical exam along with appropriate imaging are required to make the proper diagnosis. Laboratory testing does not contribute to the diagnosis of TOH and conventional radiographs can be normal in early stages of TOH. Although computed tomography can be employed, it lacks the sensitivity to detect abnormalities in TOH.4,6 Bone marrow edema can be symptomatic or asymptomatic, is primarily identified on MRI, and is useful in the identification of several pathologies such as osteomyelitis, osteonecrosis, microfracture, and osteoarthritis. Evaluation using MRI is the most sensitive and predictable test for early diagnosis of TOH.2,4,8,9

TOH is divided into three phases.7–10 In the first stage, the initial symptoms consist of hip pain that may radiate to the groin, buttocks, or thigh. Pain is increased with axial loading, and ROM is limited with bone marrow edema developing on MRI. In the second stage, no abnormalities may be seen on conventional radiographs, but demineralization of the head, neck, and intertrochanteric region of the femur occurs and is visible on MRI. These findings can develop as soon as 48 hours after symptoms begin. The third stage consists of complete resolution of symptoms clinically and radiographically.7–10

The aim of this case study is to increase awareness of the prevalence and diagnosis of TOH for medical providers who serve our military population. As mentioned earlier, the differential diagnosis for hip pain includes multiple internal and external factors. A greater level of awareness of TOH will obviate unnecessary, inefficient, or unproductive interventions such as unsuitable imaging, lab test, specialty clinic referrals, and non-prudent use of narcotic prescriptions. Transient osteoporosis of the hip is a self-limiting disease process that requires only symptomatic treatment such as basic analgesia, physical therapy, and activity modification. On average, recovery is seen within 6-12 months.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, the DoD, or the U.S. Government.