-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

John J Fraser, Andrew J MacGregor, Kenneth M Fechner, Michael R Galarneau, Factors Associated With Neuromusculoskeletal Injury and Disability in Navy and Marine Corps Personnel, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages e2049–e2057, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usac386

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Neuromusculoskeletal injuries (NMSKI) are very common in the military, which contribute to short- and long-term disability.

Population-level NMSKI, limited duty (LIMDU), and long-term disability episode counts in the U.S. Navy (USN) and U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) from December 2016 to August 2021 were extracted from the Musculoskeletal Naval Epidemiological Surveillance Tool. The incidence of NMSKI, LIMDU, and long-term disability was calculated. A hurdle negative binomial regression evaluated the association of body region, sex, age, rank, age by rank, and service branch on NMSKI, LIMDU, and long-term disability incidence.

From December 2016 to August 2021, there were 2,004,196 NMSKI episodes (USN: 3,285/1,000 Sailors; USMC: 4,418/1,000 Marines), 16,791 LIMDU episodes (USN: 32/1,000 Sailors; USMC: 29/1,000 Marines), and 2,783 long-term disability episodes (USN: 5/1,000 Sailors; USMC: 5/1,000 Marines). There was a large-magnitude protective effect on NMSKI during the pandemic (relative risk, USN: 0.70; USMC: 0.75). Low back and ankle-foot were the most common, primarily affecting female personnel, aged 25-44 years, senior enlisted, in the USMC. Shoulder, arm, pelvis-hip, and knee conditions had the greatest rates of disability, with female sex, enlisted ranks, aged 18-24 years, and service in the USMC having the most salient risk factors.

Body region, sex, age, rank, and branch were the salient factors for NMSKI. The significant protective effect during the pandemic was likely a function of reduced physical exposure and limited access to nonurgent care. Geographically accessible specialized care, aligned with communities with the greatest risk, is needed for timely NMSKI prevention, assessment, and treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Neuromusculoskeletal injuries (NMSKI) are very common in military personnel, which degrade the capability of the armed forces to meet mission objectives that contribute to national security.1 In best cases, these conditions preclude physical activity and limit the ability of a service member to function in their occupational specialties for only a limited period. More frequently, body system impairments and symptoms (such as pain) preclude function for protracted periods, which substantially affects the quality of life, increases health care costs, and degrades mission readiness.2 The association between military activity and injury is likely bidirectional since fluctuations in geopolitics and operational requirements influence the type and volume of exposure, environmental factors, and intrinsic factors associated with NMSKI in military service members.1

There are multiple factors associated with NMSKI, including sex, occupation, age, rank, and the period of study. These factors, in addition to the suspected latent factors such as care-seeking behaviors, access to care, and the mode and duration of exposure, plausibly drive these outcomes in the military.1 This likely includes periods of reduced operational demand,3–6 something that occurred during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic as the U.S. Military shifted to a health protection posture required to mitigate the spread of this respiratory illness. A decline in NMSKI over time was observed in recent studies of the military, a finding that was attributed to the change in geopolitics, decline in combat operations, return to peacetime operations, and decreased exposure to hazards incurred during training and operations.3–6 This supposition can now be assessed in a more recent study epoch, where training and non-essential operations were halted to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.7

While military personnel frequently experience rapid recovery and return to occupational duties following NMSKI, others have protracted periods of activity limitation that preclude participation in the organizational mission.2 This is especially problematic considering the associated costs and implications for national security.1,2 An assessment of the factors that may be associated with NMSKI outcomes, short-term limited duty (LIMDU), and long-term disability (medical attrition) would allow for greater precision for targeted prevention, optimization of health care delivery models, and identification of factors that may contribute to protracted care and long-term disablement. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the effects of sex, age, rank, service branch, and body region on the incidence of NMSKI, LIMDU, and long-term disability in the Department of the Navy (DoN), specifically members serving in the U.S. Navy (USN) and U.S. Marine Corps (USMC). A secondary aim was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of NMSKI.

METHODS

A population-based epidemiological retrospective cohort study of all military members in the DoN was performed to assess body region, sex, age, rank, and service branch on the incidence of NMSKI, LIMDU, and long-term disability following these injuries from December 2016 to August 2021. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement was used to guide reporting.

Neuromusculoskeletal injury episodes, LIMDU, and long-term disability (operationally defined by Disability Evaluation System [DES] referral) counts were extracted from the Musculoskeletal Naval Epidemiological Surveillance Tool (MSK NEST; Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Falls Church, VA, USA). This surveillance tool leverages existing validated databases, such as the Military Health System Data Repository, LIMDU Sailor and Marine Readiness Tracker System, DES, and Defense Manpower Data Center Reporting System to report injury burden. Neuromusculoskeletal injury episodes within the MSK NEST were derived from health care encounters in the Military Health System Data Repository and defined using the Army Public Health Center’s Taxonomy for Musculoskeletal Injuries based on an ICD-10 classification.8 Individuals with repeat visits for the same diagnosis in a single care episode were only counted once. The MSK NEST provides aggregated count data for NMSKI episodes by body region and de-identified patient characteristics that included sex; age range (18-24, 25-34, 35-44, and ≥45 years); rank (junior enlisted [E1-E5], senior enlisted [E6-E9], junior officers [O1-O3], and senior officers [O4-O10]); and service branch (USN and USMC) for all active and reserve personnel in the DoN. The database does not include any personally identifiable health information.

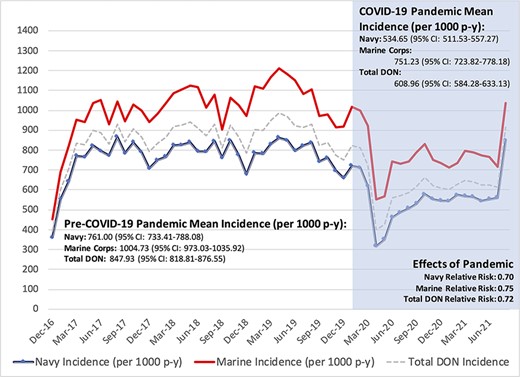

Since military end strength fluctuates annually because of attrition and recruitment of replacements,9 the population at risk was a dynamic cohort. The cumulative incidence of NMSKI was calculated and normalized to the subpopulation at risk (with consideration to sex, service branch, and rank) during the 4.75-year study epoch. Rates of LIMDU and long-term disability were calculated per 1,000 episode-years for each subpopulation. In the evaluation of the effects of COVID-19, the mean NMSKI incidence was calculated for the pre-pandemic epoch (December 2016 to March 2020) and during the pandemic (April 2020 to August 2021). Relative risk (RR) and 95% CI were calculated to assess the effects of the pandemic epoch.

A multivariable negative binomial regression was performed to evaluate the association of body region, sex, age, rank, age by rank, and service branch on the incidence of NMSKI episodes, LIMDU, and long-term disability. Because of overdispersion of the data, a negative binomial model was employed over a Poisson model.10 Since there were excess zeros noted in the data, with many demographic categories not having any reported outcomes of interest (especially among the smaller subpopulations), the assessment of convergence between the unadjusted and adjusted (hurdle) negative binomial regression models was performed. In the hurdle negative binomial regression model, a logistic link is employed to remove demographic categories that contributed no episodes of injury, LIMDU, or DES from the final count model. By doing so, excess zeros that contribute to skewed point estimates, standard errors, and overdispersion are parsed in the truncated regression model.10 Results of the hurdle negative binomial regression model are reported using calculations of the predictors regressed on count data (count model assessing the rate of the outcome), as well as a linked logistic regression (zero model that assessed the probability within demographic categories of not having the outcome). Both unadjusted and adjusted models are reported in the Supplementary material. The regression analyses were performed using the “MASS” (version 7.3-54) and “PSCL” (version 1.5) packages on R (version 3.5.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Ankle-foot injuries served as the reference in the assessment of body region. Female military personnel were selected as the reference group in the assessment of sex. The age range of 18-24 years was selected as the reference for age. Junior enlisted personnel served the reference group for rank because of the greater disease and non-battle injuries in this group compared to commissioned officers.11 Finally, the USMC was the reference group for service branch. The level of significance was P < .05 for all analyses. Statistical significance was evaluated using the convergence of RR CIs that did not cross 1.00 and the P-value reported in the regression analyses.

RESULTS

The incidence of NMSKI, NMSKI-related LIMDU, and long-term disability stratified by body region, sex, age, rank, and service branch in the USN, USMC, and DoN is reported in Supplementary Tables S1-S3. From December 2016 to August 2021, there were 2,004,196 episodes of NMSKI (USN: 3,285 episodes/1,000 Sailors; USMC: 4,418 episodes/1,000 Marines), 16,791 cases of LIMDU (USN: 32/1,000 Sailors; USMC: 29/1,000 Marines), and 2,783 cases of long-term disability (USN: 5/1,000 Sailors; USMC: 5/1,000 Marines) in the DoN. Figure 1 details the incidence of the NMSKI in the USN, USMC, and the total DoN during pre-pandemic and pandemic epochs. The pre-pandemic rate of NMSKI was 761.00 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 733.41-788.08) in the USN; 1,004.73 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 973.03-1,035.92) in the USMC; and 847.93 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 818.81-876.55) in the total DoN. During the pandemic, the rate decreased to 534.65 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 511.53-557.27) in the USN; 751.23 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 723.82-778.18) in the USMC; and 608.96 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 584.28-633.13) in the DoN, an indication of a large-magnitude protective effect (RR, USN: 0.70; USMC: 0.75; DoN: 0.72). A large inflection in the NMSKI rate was also noted in August 2021 during the final month of the study.

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on episodic neuromuscular injury incidence in the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps.

NMSKI Factors

Although the incidence of ankle-foot injuries was second to only low back conditions across the DoN (Table I, with the full hurdle model detailed in Supplementary Table S4), there were no significant differences between the rates of these conditions when assessed in the individual branches. Although male Sailors had lower risk of NMSKI compared to their female counterparts, there was no significant difference in rates observed between male and female Marines when controlling for all other factors. When compared to the 18-24-year-old group, there were higher incidence of injury observed in Sailors aged 25-44 years and lower rates in Marines aged ≥45 years. Rank was an important factor, with Navy senior enlisted demonstrating significantly higher rates and Marine junior officers with significantly lower rates of NMSKI episodes than junior enlisted. The interactions of rank by body region and rank by age on injury incidence were either non-significant or had observed singularities and were removed from the final model.

Results of the Hurdle Negative Binomial Regression Assessing Body Region, Sex, Age, Rank, and Service Branch on Risk of Neuromusculoskeletal Injury Episodes (Adjusted for Zero Inflation) in USN and U.S. Marine Corps Personnel

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Region | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Arm | 1.10 | 0.52 | 2.32 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.33 |

| Elbow | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Knee | 0.60 | 0.34 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 1.23 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 1.04 |

| Leg | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| Low back | 1.52 | 0.88 | 2.62 | 1.63 | 0.95 | 2.80 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 2.45 |

| Mid back | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| Neck | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.11 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.96 |

| Pelvis-hip | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| Shoulder | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 1.11 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.94 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

| Other | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.40 |

| Sex | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Males | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.35 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| Age range (years) | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| 25-34 | 2.01 | 1.25 | 3.24 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 2.05 | 1.57 | 1.08 | 2.28 |

| 35-44 | 1.97 | 1.18 | 3.30 | 1.48 | 0.94 | 2.32 | 1.66 | 1.11 | 2.50 |

| ≥45 | 1.13 | 0.65 | 1.94 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.06 |

| Rank | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Senior enlisted | 4.66 | 2.75 | 7.91 | 1.53 | 0.96 | 2.43 | 2.64 | 1.74 | 4.01 |

| Junior officers | 0.57 | 0.32 | 1.01 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.58 |

| Senior officers | 1.54 | 0.83 | 2.87 | 1.08 | 0.63 | 1.88 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 1.58 |

| Branch | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,011 on 39 df | 1,141 on 39 df | 2,284 on 41 df | ||||||

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Region | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Arm | 1.10 | 0.52 | 2.32 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.33 |

| Elbow | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Knee | 0.60 | 0.34 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 1.23 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 1.04 |

| Leg | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| Low back | 1.52 | 0.88 | 2.62 | 1.63 | 0.95 | 2.80 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 2.45 |

| Mid back | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| Neck | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.11 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.96 |

| Pelvis-hip | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| Shoulder | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 1.11 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.94 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

| Other | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.40 |

| Sex | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Males | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.35 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| Age range (years) | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| 25-34 | 2.01 | 1.25 | 3.24 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 2.05 | 1.57 | 1.08 | 2.28 |

| 35-44 | 1.97 | 1.18 | 3.30 | 1.48 | 0.94 | 2.32 | 1.66 | 1.11 | 2.50 |

| ≥45 | 1.13 | 0.65 | 1.94 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.06 |

| Rank | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Senior enlisted | 4.66 | 2.75 | 7.91 | 1.53 | 0.96 | 2.43 | 2.64 | 1.74 | 4.01 |

| Junior officers | 0.57 | 0.32 | 1.01 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.58 |

| Senior officers | 1.54 | 0.83 | 2.87 | 1.08 | 0.63 | 1.88 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 1.58 |

| Branch | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,011 on 39 df | 1,141 on 39 df | 2,284 on 41 df | ||||||

Abbreviations: RR: relative risk; USN: U.S. Navy. Bolded figures depict statistical significance (P < .05). Reference: body region (ankle-foot), sex (female), age (18-24 years), rank (junior enlisted), and branch (U.S. Marine Corps).

Results of the Hurdle Negative Binomial Regression Assessing Body Region, Sex, Age, Rank, and Service Branch on Risk of Neuromusculoskeletal Injury Episodes (Adjusted for Zero Inflation) in USN and U.S. Marine Corps Personnel

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Region | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Arm | 1.10 | 0.52 | 2.32 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.33 |

| Elbow | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Knee | 0.60 | 0.34 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 1.23 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 1.04 |

| Leg | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| Low back | 1.52 | 0.88 | 2.62 | 1.63 | 0.95 | 2.80 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 2.45 |

| Mid back | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| Neck | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.11 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.96 |

| Pelvis-hip | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| Shoulder | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 1.11 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.94 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

| Other | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.40 |

| Sex | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Males | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.35 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| Age range (years) | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| 25-34 | 2.01 | 1.25 | 3.24 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 2.05 | 1.57 | 1.08 | 2.28 |

| 35-44 | 1.97 | 1.18 | 3.30 | 1.48 | 0.94 | 2.32 | 1.66 | 1.11 | 2.50 |

| ≥45 | 1.13 | 0.65 | 1.94 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.06 |

| Rank | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Senior enlisted | 4.66 | 2.75 | 7.91 | 1.53 | 0.96 | 2.43 | 2.64 | 1.74 | 4.01 |

| Junior officers | 0.57 | 0.32 | 1.01 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.58 |

| Senior officers | 1.54 | 0.83 | 2.87 | 1.08 | 0.63 | 1.88 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 1.58 |

| Branch | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,011 on 39 df | 1,141 on 39 df | 2,284 on 41 df | ||||||

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Region | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Arm | 1.10 | 0.52 | 2.32 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.33 |

| Elbow | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Knee | 0.60 | 0.34 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 1.23 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 1.04 |

| Leg | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| Low back | 1.52 | 0.88 | 2.62 | 1.63 | 0.95 | 2.80 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 2.45 |

| Mid back | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| Neck | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.11 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.96 |

| Pelvis-hip | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| Shoulder | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 1.11 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.94 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

| Other | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.40 |

| Sex | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Males | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.35 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| Age range (years) | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| 25-34 | 2.01 | 1.25 | 3.24 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 2.05 | 1.57 | 1.08 | 2.28 |

| 35-44 | 1.97 | 1.18 | 3.30 | 1.48 | 0.94 | 2.32 | 1.66 | 1.11 | 2.50 |

| ≥45 | 1.13 | 0.65 | 1.94 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.06 |

| Rank | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Senior enlisted | 4.66 | 2.75 | 7.91 | 1.53 | 0.96 | 2.43 | 2.64 | 1.74 | 4.01 |

| Junior officers | 0.57 | 0.32 | 1.01 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.58 |

| Senior officers | 1.54 | 0.83 | 2.87 | 1.08 | 0.63 | 1.88 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 1.58 |

| Branch | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,011 on 39 df | 1,141 on 39 df | 2,284 on 41 df | ||||||

Abbreviations: RR: relative risk; USN: U.S. Navy. Bolded figures depict statistical significance (P < .05). Reference: body region (ankle-foot), sex (female), age (18-24 years), rank (junior enlisted), and branch (U.S. Marine Corps).

Factors of NMSKI-Related LIMDU and Long-Term Disability

Table II details the assessment of LIMDU in the USN, USMC, and total DoN (complete results of the hurdle model are detailed in Supplementary Table S5). The rates of LIMDU were significantly higher in knee, pelvis-hip, and shoulder conditions and lower in the mid back compared to ankle-foot conditions in the USN and USMC. Only Marines had lower rates of LIMDU because of neck, wrist-hand, and other conditions compared to ankle-foot conditions. The rate of NMSKI-related LIMDU was significantly lower in male Marines compared to their female counterparts and in Sailors aged ≥25 years and Marines aged ≥35 years compared to personnel aged 18-24 years. All junior enlisted had significantly higher rates of LIMDU compared to all other ranks.

Results of the Hurdle Negative Binomial Regression Assessing Body Region, Sex, Age, Rank, and Service Branch on Risk of Neuromusculoskeletal Injury-Related Episodes of Limited Duty (Adjusted for Zero Inflation) in USN and U.S. Marine Corps Personnel

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 9.61 | 4.99 | 18.49 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 1.29 | 4.48 | 2.89 | 6.94 |

| Elbow | 0.77 | 0.45 | 1.32 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 1.10 |

| Knee | 2.71 | 1.74 | 4.22 | 2.20 | 1.56 | 3.11 | 2.46 | 1.80 | 3.35 |

| Leg | 1.05 | 0.63 | 1.72 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.35 |

| Low back | 1.17 | 0.76 | 1.82 | 1.24 | 0.89 | 1.72 | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.61 |

| Mid back | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.60 |

| Neck | 0.93 | 0.59 | 1.45 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 1.05 |

| Pelvis-hip | 2.96 | 1.89 | 4.62 | 2.82 | 1.99 | 3.98 | 2.87 | 2.10 | 3.92 |

| Shoulder | 2.09 | 1.35 | 3.26 | 2.29 | 1.63 | 3.20 | 2.17 | 1.60 | 2.95 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.96 | 0.60 | 1.55 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.08 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.52 | 1.57 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.87 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.05 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| 35-44 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.88 |

| ≥45 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.56 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.07 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| Junior officers | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.61 |

| Senior officers | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.44 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,649 on 39 df | 1,466 on 39 df | 3,179 on 41 df | ||||||

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 9.61 | 4.99 | 18.49 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 1.29 | 4.48 | 2.89 | 6.94 |

| Elbow | 0.77 | 0.45 | 1.32 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 1.10 |

| Knee | 2.71 | 1.74 | 4.22 | 2.20 | 1.56 | 3.11 | 2.46 | 1.80 | 3.35 |

| Leg | 1.05 | 0.63 | 1.72 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.35 |

| Low back | 1.17 | 0.76 | 1.82 | 1.24 | 0.89 | 1.72 | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.61 |

| Mid back | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.60 |

| Neck | 0.93 | 0.59 | 1.45 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 1.05 |

| Pelvis-hip | 2.96 | 1.89 | 4.62 | 2.82 | 1.99 | 3.98 | 2.87 | 2.10 | 3.92 |

| Shoulder | 2.09 | 1.35 | 3.26 | 2.29 | 1.63 | 3.20 | 2.17 | 1.60 | 2.95 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.96 | 0.60 | 1.55 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.08 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.52 | 1.57 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.87 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.05 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| 35-44 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.88 |

| ≥45 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.56 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.07 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| Junior officers | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.61 |

| Senior officers | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.44 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,649 on 39 df | 1,466 on 39 df | 3,179 on 41 df | ||||||

Abbreviations: RR: relative risk; USN: U.S. Navy. Bolded figures depict statistical significance (P < .05). Reference: body region (ankle-foot), sex (female), age (18-24 years), rank (junior enlisted), and branch (U.S. Marine Corps).

Results of the Hurdle Negative Binomial Regression Assessing Body Region, Sex, Age, Rank, and Service Branch on Risk of Neuromusculoskeletal Injury-Related Episodes of Limited Duty (Adjusted for Zero Inflation) in USN and U.S. Marine Corps Personnel

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 9.61 | 4.99 | 18.49 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 1.29 | 4.48 | 2.89 | 6.94 |

| Elbow | 0.77 | 0.45 | 1.32 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 1.10 |

| Knee | 2.71 | 1.74 | 4.22 | 2.20 | 1.56 | 3.11 | 2.46 | 1.80 | 3.35 |

| Leg | 1.05 | 0.63 | 1.72 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.35 |

| Low back | 1.17 | 0.76 | 1.82 | 1.24 | 0.89 | 1.72 | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.61 |

| Mid back | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.60 |

| Neck | 0.93 | 0.59 | 1.45 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 1.05 |

| Pelvis-hip | 2.96 | 1.89 | 4.62 | 2.82 | 1.99 | 3.98 | 2.87 | 2.10 | 3.92 |

| Shoulder | 2.09 | 1.35 | 3.26 | 2.29 | 1.63 | 3.20 | 2.17 | 1.60 | 2.95 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.96 | 0.60 | 1.55 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.08 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.52 | 1.57 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.87 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.05 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| 35-44 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.88 |

| ≥45 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.56 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.07 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| Junior officers | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.61 |

| Senior officers | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.44 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,649 on 39 df | 1,466 on 39 df | 3,179 on 41 df | ||||||

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 9.61 | 4.99 | 18.49 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 1.29 | 4.48 | 2.89 | 6.94 |

| Elbow | 0.77 | 0.45 | 1.32 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 1.10 |

| Knee | 2.71 | 1.74 | 4.22 | 2.20 | 1.56 | 3.11 | 2.46 | 1.80 | 3.35 |

| Leg | 1.05 | 0.63 | 1.72 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.35 |

| Low back | 1.17 | 0.76 | 1.82 | 1.24 | 0.89 | 1.72 | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.61 |

| Mid back | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.60 |

| Neck | 0.93 | 0.59 | 1.45 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 1.05 |

| Pelvis-hip | 2.96 | 1.89 | 4.62 | 2.82 | 1.99 | 3.98 | 2.87 | 2.10 | 3.92 |

| Shoulder | 2.09 | 1.35 | 3.26 | 2.29 | 1.63 | 3.20 | 2.17 | 1.60 | 2.95 |

| Wrist and hand | 0.96 | 0.60 | 1.55 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.08 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.52 | 1.57 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.87 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.05 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| 35-44 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.88 |

| ≥45 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.56 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.07 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| Junior officers | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.61 |

| Senior officers | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.44 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 1,649 on 39 df | 1,466 on 39 df | 3,179 on 41 df | ||||||

Abbreviations: RR: relative risk; USN: U.S. Navy. Bolded figures depict statistical significance (P < .05). Reference: body region (ankle-foot), sex (female), age (18-24 years), rank (junior enlisted), and branch (U.S. Marine Corps).

Table III details the assessment of body region, sex, age, rank, and service branch on long-term disability (complete results, including the zero model of the hurdle negative binomial regression, are detailed in Supplementary Table S6). Sailors with arm, elbow, or knee conditions; Navy junior enlisted; and DoN personnel with pelvis-hip and shoulder conditions had the greatest incidence of long-term disability, with Marines having neck conditions and Sailors aged ≥45 years having the lowest rates of long-term disability. When the results of the hurdle model were compared to the standard negative binomial regression in the assessment of adjusted injury risk, the zero-adjusted model outperformed the non-adjusted model in each of the outcomes assessed (Supplementary Tables S7-S9).

Results of the Hurdle Negative Binomial Regression Assessing Body Region, Sex, Age, Rank, and Service Branch on Risk of Neuromusculoskeletal Injury-Related Episodes of Long-Term Disability (Adjusted for Zero Inflation) in USN and U.S. Marine Corps Personnel

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 20.04 | 7.16 | 56.09 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.96 | 14.27 | 5.88 | 34.61 |

| Elbow | 4.56 | 1.44 | 14.43 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 0.88 | 3.80 |

| Knee | 2.57 | 1.31 | 5.04 | 1.72 | 0.97 | 3.03 | 2.10 | 1.26 | 3.50 |

| Leg | 1.26 | 0.59 | 2.69 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 1.71 |

| Low back | 1.42 | 0.74 | 2.70 | 1.36 | 0.78 | 2.37 | 1.35 | 0.83 | 2.20 |

| Mid back | 1.68 | 0.69 | 4.10 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 0.53 | 1.73 |

| Neck | 1.55 | 0.79 | 3.06 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 1.23 | 1.04 | 0.61 | 1.74 |

| Pelvis-hip | 5.26 | 2.67 | 10.38 | 2.95 | 1.65 | 5.26 | 3.89 | 2.32 | 6.53 |

| Shoulder | 2.24 | 1.12 | 4.44 | 2.75 | 1.54 | 4.93 | 2.67 | 1.58 | 4.51 |

| Wrist and hand | 1.97 | 0.94 | 4.10 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 1.29 | 1.47 | 0.83 | 2.60 |

| Other | 1.57 | 0.69 | 3.54 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 1.86 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.73 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.73 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 0.80 | 1.46 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 1.10 |

| 35-44 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 1.43 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 1.27 |

| ≥45 | 1.34 | 0.62 | 2.91 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 1.36 | 0.67 | 2.76 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 1.11 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.67 |

| Junior officers | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.56 | 1.84 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| Senior officers | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 1.12 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.87 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 857 on 39 Df | 767 on 39 Df | 1,679 on 41 Df | ||||||

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 20.04 | 7.16 | 56.09 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.96 | 14.27 | 5.88 | 34.61 |

| Elbow | 4.56 | 1.44 | 14.43 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 0.88 | 3.80 |

| Knee | 2.57 | 1.31 | 5.04 | 1.72 | 0.97 | 3.03 | 2.10 | 1.26 | 3.50 |

| Leg | 1.26 | 0.59 | 2.69 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 1.71 |

| Low back | 1.42 | 0.74 | 2.70 | 1.36 | 0.78 | 2.37 | 1.35 | 0.83 | 2.20 |

| Mid back | 1.68 | 0.69 | 4.10 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 0.53 | 1.73 |

| Neck | 1.55 | 0.79 | 3.06 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 1.23 | 1.04 | 0.61 | 1.74 |

| Pelvis-hip | 5.26 | 2.67 | 10.38 | 2.95 | 1.65 | 5.26 | 3.89 | 2.32 | 6.53 |

| Shoulder | 2.24 | 1.12 | 4.44 | 2.75 | 1.54 | 4.93 | 2.67 | 1.58 | 4.51 |

| Wrist and hand | 1.97 | 0.94 | 4.10 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 1.29 | 1.47 | 0.83 | 2.60 |

| Other | 1.57 | 0.69 | 3.54 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 1.86 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.73 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.73 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 0.80 | 1.46 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 1.10 |

| 35-44 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 1.43 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 1.27 |

| ≥45 | 1.34 | 0.62 | 2.91 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 1.36 | 0.67 | 2.76 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 1.11 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.67 |

| Junior officers | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.56 | 1.84 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| Senior officers | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 1.12 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.87 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 857 on 39 Df | 767 on 39 Df | 1,679 on 41 Df | ||||||

Abbreviations: RR: relative risk; USN: U.S. Navy. Bolded figures depict statistical significance (P < .05); Reference: body region (ankle-foot), sex (female), age (18-24 years), rank (junior enlisted), and branch (U.S. Marine Corps).

Results of the Hurdle Negative Binomial Regression Assessing Body Region, Sex, Age, Rank, and Service Branch on Risk of Neuromusculoskeletal Injury-Related Episodes of Long-Term Disability (Adjusted for Zero Inflation) in USN and U.S. Marine Corps Personnel

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 20.04 | 7.16 | 56.09 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.96 | 14.27 | 5.88 | 34.61 |

| Elbow | 4.56 | 1.44 | 14.43 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 0.88 | 3.80 |

| Knee | 2.57 | 1.31 | 5.04 | 1.72 | 0.97 | 3.03 | 2.10 | 1.26 | 3.50 |

| Leg | 1.26 | 0.59 | 2.69 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 1.71 |

| Low back | 1.42 | 0.74 | 2.70 | 1.36 | 0.78 | 2.37 | 1.35 | 0.83 | 2.20 |

| Mid back | 1.68 | 0.69 | 4.10 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 0.53 | 1.73 |

| Neck | 1.55 | 0.79 | 3.06 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 1.23 | 1.04 | 0.61 | 1.74 |

| Pelvis-hip | 5.26 | 2.67 | 10.38 | 2.95 | 1.65 | 5.26 | 3.89 | 2.32 | 6.53 |

| Shoulder | 2.24 | 1.12 | 4.44 | 2.75 | 1.54 | 4.93 | 2.67 | 1.58 | 4.51 |

| Wrist and hand | 1.97 | 0.94 | 4.10 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 1.29 | 1.47 | 0.83 | 2.60 |

| Other | 1.57 | 0.69 | 3.54 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 1.86 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.73 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.73 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 0.80 | 1.46 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 1.10 |

| 35-44 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 1.43 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 1.27 |

| ≥45 | 1.34 | 0.62 | 2.91 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 1.36 | 0.67 | 2.76 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 1.11 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.67 |

| Junior officers | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.56 | 1.84 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| Senior officers | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 1.12 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.87 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 857 on 39 Df | 767 on 39 Df | 1,679 on 41 Df | ||||||

| . | USN . | U.S. Marine Corps . | Total . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | . | 95% CI . | |||

| . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . | RR . | LL . | UL . |

| Body region | |||||||||

| Arm | 20.04 | 7.16 | 56.09 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.96 | 14.27 | 5.88 | 34.61 |

| Elbow | 4.56 | 1.44 | 14.43 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 0.88 | 3.80 |

| Knee | 2.57 | 1.31 | 5.04 | 1.72 | 0.97 | 3.03 | 2.10 | 1.26 | 3.50 |

| Leg | 1.26 | 0.59 | 2.69 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 1.71 |

| Low back | 1.42 | 0.74 | 2.70 | 1.36 | 0.78 | 2.37 | 1.35 | 0.83 | 2.20 |

| Mid back | 1.68 | 0.69 | 4.10 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 0.53 | 1.73 |

| Neck | 1.55 | 0.79 | 3.06 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 1.23 | 1.04 | 0.61 | 1.74 |

| Pelvis-hip | 5.26 | 2.67 | 10.38 | 2.95 | 1.65 | 5.26 | 3.89 | 2.32 | 6.53 |

| Shoulder | 2.24 | 1.12 | 4.44 | 2.75 | 1.54 | 4.93 | 2.67 | 1.58 | 4.51 |

| Wrist and hand | 1.97 | 0.94 | 4.10 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 1.29 | 1.47 | 0.83 | 2.60 |

| Other | 1.57 | 0.69 | 3.54 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 1.86 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 0.73 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.73 |

| Age range (years) | |||||||||

| 25-34 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 0.80 | 1.46 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 1.10 |

| 35-44 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 1.43 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 1.27 |

| ≥45 | 1.34 | 0.62 | 2.91 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 1.36 | 0.67 | 2.76 |

| Rank | |||||||||

| Senior enlisted | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 1.11 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.67 |

| Junior officers | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.56 | 1.84 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| Senior officers | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 1.12 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.87 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| USN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| Negative log-likelihood | 857 on 39 Df | 767 on 39 Df | 1,679 on 41 Df | ||||||

Abbreviations: RR: relative risk; USN: U.S. Navy. Bolded figures depict statistical significance (P < .05); Reference: body region (ankle-foot), sex (female), age (18-24 years), rank (junior enlisted), and branch (U.S. Marine Corps).

DISCUSSION

The primary findings of this study were that during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a significant protective effect for NMSKI that was likely a function of reduced physical exposure and limited access to nonurgent care. In the broader assessment of body region, sex, age, rank, and service branch on burden between 2016 and 2021, low back and ankle-foot were the most common of all NMSKI in the DoN, primarily affecting female personnel, service members aged 25-44 years, senior enlisted, and Marines. Among the cases of LIMDU and long-term disability, female enlisted Marines, service members aged 18-24 years, and those with shoulder, arm, pelvis-hip, and knee conditions demonstrated the greatest risk. This is the first study to the authors’ knowledge to investigate the effects of the pandemic on NMSKI in the military, as well as the burden of NMSKI-related LIMDU and disability across the USN and USMC.

NMSKI Burden

The protective effect observed during the COVID-19 pandemic is likely attributable to a shift in operations to only mission-critical tasks since infectious disease prophylaxis was prioritized for force health protection. Medical operations similarly pivoted to urgent and emergent care, with the capability to provide and document routine care in the electronic health record substantially curtailed. As such, reduced exposure to potentially injurious activities during military operations, combined with reduced routine health care utilization and documentation for NMSKI during the pandemic, is likely responsible for the reduction in reported NMSKI incidence. A similar phenomenon has been observed in NMSKI-related emergency department visits and surgical procedures in civilian hospitals.12 The rapid increase in incidence in the latter months of the study epoch corresponds with a period of resumption of regular operations, including preparation for the fall physical readiness assessment required by the USN and USMC in 2021.

The findings of increased risk of NMSKI in female service members are consistent with recent studies assessing sex within military occupation and across service branches.3–5,13 Occupational exposures differ between enlisted and officer personnel, with the former typically employed in vocational/technical fields and the latter responsible for the administration and supervision of their subordinates. This may explain the lower NMSKI risk in the officer staff. Even within the enlisted ranks, exposures change as more senior personnel assume supervisory and administrative roles. However, the substantially higher injury risk in senior enlisted personnel can be explained. It is highly conceivable that enlisted personnel who did not seek care for NMSKI earlier in their career may experience persistent symptoms, impairments, and activity limitation from chronic injury,1 conditions that require documentation for post-retirement, service-connected disability compensation. It is also plausible that social determinants of care-seeking, such as stigma, social pressures, and access to NMSKI care improved as members advanced in rank. Differences in service cultures between the USN and USMC may influence care-seeking determinants (e.g., mission over self; perceptions of weakness or NMSKI as self-limiting).1 In addition, differences in access to care (geographic and time-based barriers) and exposure based on the specific mission requirements (with vastly different occupational demands and hazards) may also explain why the USMC had a significantly larger risk compared to the USN.1 These suppositions warrant future investigation.

LIMDU and Long-Term Disability

Short-term LIMDU and long-term disability were most common in conditions of the shoulder, arm, pelvis-hip, and knee. Impairments in these regions can limit an individual’s ability to push, pull, lift, kneel, squat, and negotiate terrain, ladders, and stairs during occupational tasks. They also affect a service member’s ability to perform the annual physical fitness assessments used in the USN and USMC.14,15 These assessments encompass a timed running event (USN: 2.4 km, USMC: 4.8 km), a timed plank event (USN and USMC) or crunches (USMC), and an upper extremity endurance event (maximum push-ups [USN and USMC] or pull-ups [USMC] in 2 minutes).14,15 Since the performance of the biannual physical fitness assessment is a requirement in both the USN and USMC,14,15 it is not uncommon for clinicians to use performance on these tasks as criteria when making return to duty determination. Interestingly, service members frequently have low confidence in their ability to perform occupational and physical readiness requirements following NMSKI, with persistent pain and reinjury common in personnel returned to full duty.16 The associations between neuromusculoskeletal impairment, perceptual and psychological factors, pain, and physical activity in personnel with injuries warrant further exploration.

Female sex, junior enlisted, service members aged 18-24 years, and Marines demonstrated the greatest risk of short-term LIMDU and long-term disability. Female sex has been found to be a salient factor for activity limitations and disability in veterans, but not active duty personnel, in a study of data derived from the U.S. Census.17 This divergence may be attributed to changing roles of female personnel, with the current study epoch occurring following a policy change that opened all military occupations to women.18 Higher disability in younger, junior enlisted members is likely a function of occupation-related physical demand. Senior enlisted and officer staff members are often able to continue performing administrative duty requirements while resting, rehabilitating, and recovering from NMSKI, whereas more junior personnel with highly physical occupations often cannot. The lower rates of disability in older, more senior personnel are also likely attributed to the retirement benefit. In these groups, personnel are either emotionally or financially vested in the system (especially when they have more than 10 years of service toward the 20-year retirement) but are too young to retire. It is also plausible that the probability of experiencing a disabling condition following NMSKI that would preclude continued military service is substantially reduced because of lower exposure in the more senior personnel.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. First, this study relied on deidentified, aggregated data provided in the NEST database. Although this allowed us to ascertain the population-level burden of NMSKI incidence, short-term LIMDU, and long-term disability, the lack of individual-level data precluded the assessment of comorbidities and other intrinsic factors that may have contributed to the outcomes under study. The NEST database only provided data from the USN and USMC, which precluded assessment of the other branches of the U.S. military and a comparison of service-related differences. Since this study relied on encounters in the electronic health record, the true burden of NMSKI (to include injuries that were self-managed) is likely much greater than that reported in this study. Lastly, the ability to evaluate the post-pandemic NMSKI burden was limited based on data availability and timing of this study. Empirical evaluation of these outcomes during the post-pandemic period is certainly warranted in future studies.

Clinical Practice and Policy Implications

From a medical planning perspective, the allocation of geographically accessible specialized care and resources needed for the timely prevention, assessment, and treatment of NMSKI should be aligned with communities that have the greatest risk.1 This evidence helps to prioritize the allocation of staffing and supplies needed to address the populations with the greatest risk of injury, short-term LIMDU, and long-term disability in order to optimize readiness. Although global pandemics are infrequent and only occur once every few generations, the release of biological agents by nations and non-state actors is a persistent threat to the readiness of the armed forces. It is paramount that military leadership considers the physical and operational readiness of personnel during periods of restricted movement and reduced social interaction (e.g., pandemics).

CONCLUSION

There was a significant protective effect during the COVID-19 pandemic that was likely a function of reduced physical exposure and access to nonurgent care. In the broader assessment, injuries to the low back and ankle-foot were the most common of all NMSKI in the DoN, affecting a higher proportion of female personnel, those aged 25-44 years, senior enlisted, and members of the USMC. Among the cases of LIMDU and long-term disability, conditions of the shoulder and arm in the upper quarter and pelvis-hip and knee in the lower quarter had the greatest burden, with personnel who were female, enlisted, aged 18-24 years, and serving in the USMC having the greatest risk.

Patient and Public Involvement

The results of this study were provided to the Office of the Medical Officer of the Marine Corps and to the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Neuromusculoskeletal Clinical Community for dissemination and translation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None declared.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at Military Medicine online.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

CDR Fraser reports grants from Defense Health Agency, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, and the Office of Naval Research, outside of the submitted work. In addition, CDR Fraser has a patent pending for an Adaptive and Variable Stiffness Ankle Brace, U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 63254,474.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be available on request.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

Not applicable.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD (HUMAN SUBJECTS)

The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center’s Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center, Institutional Review Board protocol number NHRC.2022.0201.NHSR.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC)

Not applicable.

INSTITUTIONAL CLEARANCE

Institutional clearance approved.

INDIVIDUAL AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

J.J.F. contributed to the design, data acquisition, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final product.

REFERENCES

Author notes

The study was archived as a preprint on medRxiv and is available at doi: 10.1101/2022.06.09.22276233

The authors are military service members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of our official duties. Title 17 of U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17 of U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, DoD, or the U.S. Government.