-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sílvia Roure, Xavier Vallès, Olga Pérez-Quílez, Israel López-Muñoz, Anna Chamorro, Elena Abad, Lluís Valerio, Laura Soldevila, Ester Gorriz, Dolores Herena, Elia Fernández Pedregal, Sergio España, Cristina Serra, Raquel Cera, Ana Maria Rodríguez, Lorena Serrano, Gemma Falguera, Alaa H A Hegazy, Gema Fernández-Rivas, Carmen Miralles, Carmen Conde, Juan José Montero-Alia, Jose Miranda-Sánchez, Josep M Llibre, Mar Isnard, Josep Maria Bonet, Oriol Estrada, Núria Prat, Bonaventura Clotet, The Schisto-Stop study group, Female genitourinary schistosomiasis-related symptoms in long-term sub-Saharan African migrants in Europe: a prospective population-based study, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 31, Issue 6, August 2024, taae035, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taae035

Close - Share Icon Share

Main text

Schistosomiasis can involve the genital tract in up to 75% of women with urinary Schistosoma haematobium infection in endemic countries, a phenomenon known as female genital schistosomiasis (FGS).1,2 It is characterized by an amalgamation of gynaecological signs and symptoms, mainly including menstrual disturbances and vulvovaginal discomfort. The observation of eggs in the genitourinary tract or the characteristic lesions at colposcopy examination is not the rule.1,2 The burden of FGS in African migrant women in non-endemic countries, carrying long-term or chronic S. haematobium infections, is unknown.

We performed a prospective, community-based, cross-sectional study in two municipalities of the Northern Metropolitan area of Barcelona (Spain), with a high prevalence of migrant population. We explored the presence of standardized genitourinary-related clinical signs and symptoms3 among migrant women from Sub-Saharan Africa (mainly West Africa), associated to a positive Schistosoma test [Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and/or Immunochromatography (ICT) and/or microscopic urine examination]. Clinical data were collected through the revision of electronic health records and a one-to-one pre-tested individual questionnaire, including a list of genitourinary signs and symptoms for which no aetiological diagnosis had been determined. Data were analysed using Stata vs. 15 and R vs. 3.3.2. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol (Badalona, Spain) and the Jordi Gol Foundation, with certification number 22/063-P.

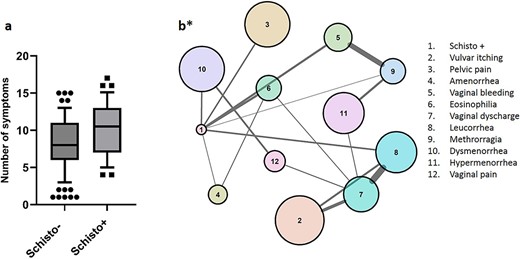

Between April and November 2022, we enrolled 134 eligible women, with a mean age 40.5 (SD = 9.4) years, and a median time since migration to European Union (EU) of 14 years (Inter-quartile range 9–19). The most frequent countries of origin were Senegal (63; 47.0%) and Gambia (32; 23.9%). Among them, 38 (28.4%) had a positive schistosomiasis test: 10 with positive ELISA alone (7.5%), 14 with an ICT positive alone (10.4%) and 13 both positive (9.7%). S. haematobium eggs were observed in urine microscopy in only one (0.8%) woman who had a negative serology. The prevalence of history of signs/symptoms associated with a Schistosomiasis positive serology was: 78.9% for dysmenorrhea [odds ratio (OR) vs women with a negative serology = 2.64; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.1–6.3], 73.7% for leucorrhoea (OR = 3.42; 95% CI:1.4–8.4), 65.8% for vaginal discharge (OR = 2.53; 95% CI:1.2–5.6), 47.4% for amenorrhea (OR = 3.91; 95% CI:1.7–8.9) and 55.3% for history of eosinophilia (OR = 4.28; 95% CI:1.9–9.6). The median of signs/symptoms was 11 vs 8 in women with positive vs negative serology, respectively (P = 0.009; Figure 1a). Symptoms tended to present associated in clusters (Figure 1b), led by vaginal bleeding or discharge, leucorrhoea, vaginal pain and menstrual abnormalities. Infertility, defined as having had an episode of more than 6 months without getting pregnant with conception interest and not using any contraceptive methods, was common among women with a positive serology (55.4%). The direct questionnaire identified significantly more signs/symptoms than the electronic medical record review. Furthermore, data about colposcopy examination were available for only seven women. Of these seven, five had abnormal macroscopic findings compatible with FGS according to the WHO guidelines.4

Box plot of number of genitourinary and reproductive symptoms stratified by positive and negative Schistosoma serology (a) and network analysis results (b*). *Every clinical item is a node. The size of the node correlates with the number of individuals with the given condition. An edge between nodes (variables) indicates a statistically significant association between them. The thickness of the edges indicates the strength of the association, which correlates with the number of times that both items appear together in the data set. A more central situation of the node indicates a higher centrality score, which can be interpreted as a higher influence (higher density of connections) over the network. Note that the working case definition, which included serology and clinical based criteria, should not be considered a diagnostic for FGS which cannot be performed with the lack of reliable microbiological identification of parasites

These results suggest that sub-Saharan African migrant women with a positive Schistosoma serology unexpectedly present a profuse history of gynaecological and urinary unexplained complaints, despite living for years/decades in a non-endemic European country. These results indicate that chronic or long-lasting genitourinary schistosomiasis may be an underestimated condition in non-endemic countries, with a significant negative impact on sexual and reproductive health of migrant women. Some particular findings deserve to be highlighted, like the significant association between Schistosoma positive test and amenorrhea, which might correspond to late stages of the inflammatory processes, as described in the Asherman syndrome, a rare condition characterized due to chronic inflammatory processes of the uterine mucosa.5 Whether these women have chronic persistent infection or just long-term sequelae of currently inactive infections is unknown.

The long-term residence in Spain of our study sample (median of 14 years) shows that the diagnosis or suspicion of genitourinary schistosomiasis can be very often overlooked or delayed among African migrant females in non-endemic countries. This in turn may have contributed to the development of long-term lesions, frequently associated to fibrotic lesions. The low awareness of clinicians about schistosomiasis in non-endemic countries, the barriers to access to health care among migrant populations in Europe6 and the stigma surrounding sexual and reproductive health among African women seem the main contributors of this delayed diagnosis. African women constitute a double vulnerable population both as women and as migrants. Finally, current guidelines in Europe consider schistosomiasis screening uniquely among recent migrants (<5 years) arrived from endemic countries.7

The diagnosis of chronic FGS remains a major challenge, because there is currently no widely available, sensitive and non-invasive standard method for the microbiological confirmation of active infection. We could actually confirm the presence of urine eggs in just a single serology-negative case. Serology tests probably lack sensitivity and specificity towards chronic schistosomiasis infection, especially among long-term exposed individuals.8 Furthermore, chronic schistosomiasis manifestations might be rather driven by the secondary inflammatory and fibrotic sequelae, with limited utility of microbiology-based tests. Overall, this supports the use of a combination of serology and/or clinical-based criteria for the screening of signs and symptoms related to genital involvement of schistosomiasis infection in women, with the use of an on-site-directed questionnaire which showed higher sensitivity in our study sample.

Finally, the treatment of chronic schistosomiasis has not been fully ascertained. The dosage and duration of praziquantel are unknown,9,10 and evolving fibrotic lesions should be refractory to it. However, given the high tolerability and safety of this gold-standard drug, an empiric treatment course in exposed serology-positive women with clinically compatible and unexplained genitourinary signs and symptoms could be worthwhile.

In conclusion, genital involvement of chronic schistosomiasis among African migrant women deserves more attention in non-endemic regions with substantial pockets of migrant populations. Future research is urgently needed on the development of a gold standard diagnostic, the determination of the treatment regimen, the true characterization of chronic FGS and their prevalence and to leverage of barriers to diagnosis of this condition among women.

CRediT author contributions

Sílvia Roure (Investigation [lead], Methodology [equal], Project administration [equal], Supervision [equal], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Xavier Vallès (Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Olga Pérez-Quílez (Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Israel López-Muñoz (Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Anna Chamorro (Data curation [equal], Methodology [equal], Supervision [equal], Validation [equal]), Elena Abad (Data curation [equal], Methodology [equal], Supervision [equal], Validation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Lluís Valerio (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal] Laura Soldevila (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Ester Gorriz (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Dolores Herena (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]) Elia Fernández Pedregal (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Sergio España (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Cristina Serra (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Raquel Cera (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Ana Maria Rodríguez (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Lorena Serrano (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Gemma Falguera (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Alaa H.A. Hegazy (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Gema Fernández-Rivas (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Carmen Miralles (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Carmen Conde (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Juan José Montero Alia (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]) Jose Miranda-Sánchez (Investigation [equal], Resources [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Josep M. Llibre (Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Mar Isnard (Project administration [equal], Resources [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Josep Maria Bonet (Project administration [equal], Resources [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Oriol Estrada (Funding acquisition [equal], Resources [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Núria Prat (Funding acquisition [equal], Resources [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]) and Bonaventura Clotet (Funding acquisition [equal], Resources [equal], Supervision [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal])

Funding

The study was funded by the Fundació Lluita contra les Infeccions (Badalona, Spain).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jordi Aceiton, Marcos Montoro and Esteve Muntada for their assistance on graph’s design.

Author contributions

Sílvia Roure, Xavier Vallès and Olga Pérez-Quílez contributed in the conception and study design. Sílvia Roure, Olga Pérez-Quílez, Israel López-Muñoz, Anna Chamorro, Elena Abad, Lluís Valerio, Laura Soldevila, Ester Gorriz, Dolores Herena, Elia Fernández Pedregal, Sergio España, Cristina Serra, Raquel Cera, Ana Maria Rodríguez, Lorena Serrano, Gemma Falguera, Alaa H.A. Hegazy, Gema Fernández-Rivas, Carmen Miralles, Carmen Conde, Juan José Montero Alia, Jose Miranda-Sánchez, Mar Isnard, Josep Maria Bonet, Oriol Estrada, Núria Prat, Bonaventura Clotet and remaining Study Group member were involved in the field work and data collection. Elena Abad and Anna Chamorro were responsible of data curation. Alaa H.A. Hegazy and Gema Fernández-Rivas were responsible of laboratory procedures. Sílvia Roure, iol Estrada, Núria Prat and Bonaventura Clotet were responsible of resources management and general supervision of the work. Xavier Vallès was responsible of data analysis. Sílvia Roure, Xavier Vallès and Josep M. Llibre write the first draft of the article which was subsequently revised and approved by all co-authors.

Conflict interest

None declared.

References

WHO.

Author notes

Schisto-Stop study group: Montserrat Riera, BSc, Núria Rovira, BSc, Mayra Segura, BSc, Susana Escoda, BSc, Janeth Karin Villalaz-Gonzales, BSc, Maria Jesús Delgado, BSc, Iciar Ferre-García, BSc, Sandra Santamaria, BSc, Marilen Matero, BSc.