-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sergio España-Cueto, Inés Oliveira-Souto, Fernando Salvador, Lidia Goterris, Begoña Treviño, Adrián Sánchez-Montalvá, Núria Serre-Delcor, Elena Sulleiro, Virginia Rodríguez, Maria Luisa Aznar, Pau Bosch-Nicolau, Juan Espinosa-Pereiro, Diana Pou, Israel Molina, Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome following a diagnosis of traveller’s diarrhoea: a comprehensive characterization of clinical and laboratory parameters, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 30, Issue 6, August 2023, taad030, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taad030

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Prolonged or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms may persist after acute traveller’s diarrhoea (TD), even after adequate treatment of the primary cause. This study aims to describe the epidemiological, clinical and microbiological characteristics of patients with post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) after returning from tropical or subtropical areas.

We conducted a retrospective study of patients presenting between 2009 and 2018 at the International Health referral centre in Barcelona with persistent gastrointestinal symptoms following a diagnosis of TD. PI-IBS was defined as the presence of persistent or recurrent gastrointestinal manifestations for at least 6 months after the diagnosis of TD, a negative stool culture for bacterial pathogens and a negative ova and parasite exam after targeted treatment. Epidemiological, clinical and microbiological variables were collected.

We identified 669 travellers with a diagnosis of TD. Sixty-eight (10.2%) of these travellers, mean age 33 years and 36 (52.9%) women, developed PI-IBS. The most frequently visited geographical areas were Latin America (29.4%) and the Middle East (17.6%), with a median trip duration of 30 days (IQR 14–96). A microbiological diagnosis of TD was made in 32 of these 68 (47%) patients, 24 (75%) of whom had a parasitic infection, Giardia duodenalis being the most commonly detected parasite (n = 20, 83.3%). The symptoms persisted for a mean of 15 months after diagnosis and treatment of TD. The multivariate analysis revealed that parasitic infections were independent risk factors for PI-IBS (OR 3.0, 95%CI 1.2–7.8). Pre-travel counselling reduced the risk of PI-IBS (OR 0.4, 95%CI 0.2–0.9).

In our cohort, almost 10% of patients with travellers’ diarrhoea developed persistent symptoms compatible with PI-IBS. Parasitic infections, mainly giardiasis, seem to be associated with PI-IBS.

Introduction

Traveller’s diarrhoea (TD) is one of the commonest travel-related illnesses, affecting around 10–40% of people travelling to low- and middle-income countries.1 TD is normally associated with a benign outcome; however, in some cases, prolonged or recurrent functional gastrointestinal disorders may persist after infection clearance.2,3

Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) is characterized by prolonged abdominal pain or discomfort accompanied by diarrhoea and/or constipation as well as dietary intolerances after acute infection.3,4 PI-IBS has been described following extraintestinal infections (e.g. respiratory or urinary tract infections), but gastrointestinal infections, including TD, seem to have a higher risk of developing PI-IBS.5,6

The occurrence of PI-IBS after acute gastroenteritis (AGE) has been demonstrated in several studies.7–9 A recent meta-analysis reported a PI-IBS incidence ranging from 3% to 30% after a TD episode10; other studies with long-term follow-up reported that PI-IBS could persist in >50% of cases after 6 years.11 Different factors have been associated with PI-IBS occurrence: host characteristics (age and sex), AGE severity or the microbiological aetiology of the previous gastrointestinal disorder. One of the highest PI-IBS incidences (36% at 2 years) was described after an outbreak in Walkerton (Ontario, Canada), where a double infection with Campylobacter jejuni and Escherichia coli O157:H7 was detected.12 Chronic fatigue has also been well described as a persistent symptom after AGE, specifically after Giardia duodenalis infection.13–15

This study aims to describe the epidemiological, clinical and microbiological characteristics of adult patients presenting PI-IBS following a prior diagnosis of TD. We also evaluated possible risk factors associated with PI-IBS.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study performed at the International Health Unit Vall d’Hebron-Drassanes of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, a tertiary hospital included in the International Health Programme of the Catalan Health Institute (PROSICS Barcelona, Spain); it is a reference centre for International Health pathology in the region. Patients who fulfilled PI-IBS criteria were included among the cohort of patients with TD aged 18 years or older diagnosed between January 2009 and January 2018. The characteristics of the cohort of patients with TD after returning from an international trip were described elsewhere.16

PI-IBS was defined as chronic and recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort (at least once per week) for at least 6 months, meeting two Rome IV criteria (related to defecation, associated with a change in stool frequency and/or associated with a change in stool form).17,18 Rome IV criteria were taken into account as they had already been established when this study was designed and performed.19–21 However, there would have been differences in PI-IBS prevalence if Rome III criteria had been used, as Rome IV criteria are more restrictive.

Firstly, the general registry of the Unit was consulted, providing information regarding adult patients presenting TD from 2009 and 2018. Next, we selected those patients who developed symptoms suggestive of PI-IBS within 6 months after returning from international travel. The inclusion criteria were: age 18 years or older, PI-IBS onset within 6 months following a TD diagnosis and no history of underlying gastrointestinal disease prior to international travel.

Data were collected from all patients: epidemiological (age, sex, duration of the trip associated with the TD, geographical area visited), clinical (clinical symptoms, duration of symptoms, treatment received) and microbiological results. TD with a definite aetiology was that in which one or more microbiological tests were positive. Related to this, some parasites and protists of uncertain pathogenicity (Blastocystis spp. or Dientamoeba fragilis) were not considered to cause the TD, even if no other cause for the diarrhoea was found.22,23

Additionally, patients who developed symptoms suggestive of PI-IBS were contacted by telephone (up to three times) between June and July 2022 and, after consenting verbally, were asked about the evolution of their symptoms after the TD diagnosis, treatment received and how this condition affected their quality of life. The disease severity was classified as slight (tolerable, not distressing and does not interfere with planned activities), moderate (distressing or interferes with planned activities) or severe (incapacitating or completely prevents planned activities) according to the literature.24

Moreover, all respondents answered a standardized and validated questionnaire to assess the risk of developing PI-IBS during the TD episode. This tool consists of nine items (Table 1) that are assessed with close-ended questions.25 In order to minimize variations, a single researcher conducted all telephone interviews.

| RISK FACTOR . | CATEGORY . | POINTS . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤60 years | 6 |

| >60 years | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 0 |

| Female | 9 | |

| REPORTED SYMPTOMS DURING ACUTE ILLNESS | ||

| Duration of diarrhoea (days) | ≤7 days | 0 |

| >7 days | 7 | |

| Maximum number of loose stools per day during acute illness | ≤6>6 | 08 |

| Bloody stools | None | 0 |

| Yes | 4 | |

| Abdominal cramps | None | 0 |

| Yes | 32 | |

| Fever | None | 0 |

| Yes | 5 | |

| Weight loss > 4.5 Kg | None | 0 |

| Yes | 8 | |

| SELF-REPORTED PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDER | ||

| Anxiety, Depression | None | 0 |

| Pre-infection | 1 | |

| Post-infection | 10 | |

| Total | /90 | |

| RISK FACTOR . | CATEGORY . | POINTS . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤60 years | 6 |

| >60 years | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 0 |

| Female | 9 | |

| REPORTED SYMPTOMS DURING ACUTE ILLNESS | ||

| Duration of diarrhoea (days) | ≤7 days | 0 |

| >7 days | 7 | |

| Maximum number of loose stools per day during acute illness | ≤6>6 | 08 |

| Bloody stools | None | 0 |

| Yes | 4 | |

| Abdominal cramps | None | 0 |

| Yes | 32 | |

| Fever | None | 0 |

| Yes | 5 | |

| Weight loss > 4.5 Kg | None | 0 |

| Yes | 8 | |

| SELF-REPORTED PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDER | ||

| Anxiety, Depression | None | 0 |

| Pre-infection | 1 | |

| Post-infection | 10 | |

| Total | /90 | |

| RISK FACTOR . | CATEGORY . | POINTS . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤60 years | 6 |

| >60 years | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 0 |

| Female | 9 | |

| REPORTED SYMPTOMS DURING ACUTE ILLNESS | ||

| Duration of diarrhoea (days) | ≤7 days | 0 |

| >7 days | 7 | |

| Maximum number of loose stools per day during acute illness | ≤6>6 | 08 |

| Bloody stools | None | 0 |

| Yes | 4 | |

| Abdominal cramps | None | 0 |

| Yes | 32 | |

| Fever | None | 0 |

| Yes | 5 | |

| Weight loss > 4.5 Kg | None | 0 |

| Yes | 8 | |

| SELF-REPORTED PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDER | ||

| Anxiety, Depression | None | 0 |

| Pre-infection | 1 | |

| Post-infection | 10 | |

| Total | /90 | |

| RISK FACTOR . | CATEGORY . | POINTS . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤60 years | 6 |

| >60 years | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 0 |

| Female | 9 | |

| REPORTED SYMPTOMS DURING ACUTE ILLNESS | ||

| Duration of diarrhoea (days) | ≤7 days | 0 |

| >7 days | 7 | |

| Maximum number of loose stools per day during acute illness | ≤6>6 | 08 |

| Bloody stools | None | 0 |

| Yes | 4 | |

| Abdominal cramps | None | 0 |

| Yes | 32 | |

| Fever | None | 0 |

| Yes | 5 | |

| Weight loss > 4.5 Kg | None | 0 |

| Yes | 8 | |

| SELF-REPORTED PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDER | ||

| Anxiety, Depression | None | 0 |

| Pre-infection | 1 | |

| Post-infection | 10 | |

| Total | /90 | |

Categorical data were presented as absolute numbers and proportions, and continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) depending on the distribution. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate the normal distribution of variables. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate, was used to compare the distribution of categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis compared the characteristics of TD patients with and without persistent symptoms to identify factors associated with PI-IBS. Quantitative variables were transformed into dichotomous variables taking into account the median value. Variables entered the model if P < 0.25 upon univariate analysis. Results were considered statistically significant if the 2-tailed P-value was <0.05. SPSS software for Windows (15.0 Version, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Vall d’Hebrón University Hospital (Barcelona, Spain) (PR(AG)191/2022). Procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013.

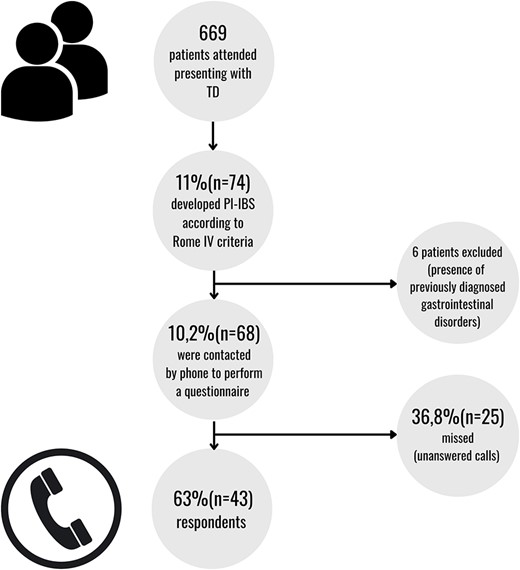

Stepwise approach for the follow-up of patients presenting with PI-IBS

Results

Between January 2009 and January 2018, 669 patients with a diagnosis of TD were attended, of which 74 (11.1%) developed PI-IBS within 6 months after returning from international travel. Six patients were excluded due to a previous diagnosis of gastrointestinal disorders; thus, 68 (10.2%) patients were included in this study (see Figure 1). Thirty-six of the 68 (52.9%) were women, the mean age was 33 (SD 10.6) years and no one had an immunodeficiency disorder.

Regarding prior travel and the initial TD diagnosis (Table 2), tourism was the main purpose of travelling (n = 45; 66.2%) followed by ‘Visiting Friends and Relatives’ (VFR; n = 11; 16.2%). The geographical areas most frequently visited were Latin America (n = 20; 29.4%) and the Middle East (n = 12; 17.6%) (Supplementary material), and the median duration of the trip was 30 (IQR 14–96) days. Regarding clinical manifestations during the acute episode, the median duration of symptoms was 30 (IQR 12–120) days, with a mean number of bowel movements per day of 6 (SD 3.8). Symptoms started during travel in 49 of the 68 cases (72.1%), the most frequent accompanying symptoms being abdominal pain (67.6%), fever (41.2%) and dysentery (32.4%).

| . | n = 68 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 32 (47.1%) |

| Female | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Mean age (in years) | 33 (SD 10.6) | |

| Purpose of the travel | Tourism | 45 (66.2%) |

| VFR | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Work | 7 (10.3%) | |

| Cooperation | 5 (7.4%) | |

| Geographical areas visited | Latin America | 20 (29.4%) |

| Middle East | 12 (17.6%) | |

| Oceania and South-East Asia | 12 (17.6) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 7 (10.3) | |

| North Africa | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Median duration of the trip (in days) | 30 (IQRS 14–96) | |

| Median duration of symptoms (in days) | 30 (IQR 12–120) | |

| Mean number of bowel movements per day | 6 (SD 3.9) | |

| Symptoms onset | During the trip | 49 (72.1%) |

| After the trip | 19 (27,9%) | |

| Clinical picture | Abdominal pain | 46 (32.4%) |

| Fever | 28 (41.2%) | |

| Dysentery | 22 (32.4%) | |

| Nausea | 20 (29.4%) | |

| Vomiting | 14 (20.6%) | |

| Aetiology | Parasitic infection | 24 (35.3%) |

| Bacterial infection | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Mixed infection | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Unknown | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Parasites and protists detected | Giardia duodenalis | 20 (29.4%) |

| Blastocystis spp. | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Bacteria detected | Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli | 3 (4.4%) |

| Enteroinvasive E. coli | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Enterotoxigenic E. coli | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Shigella spp. | 2 (2.9%) | |

| . | n = 68 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 32 (47.1%) |

| Female | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Mean age (in years) | 33 (SD 10.6) | |

| Purpose of the travel | Tourism | 45 (66.2%) |

| VFR | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Work | 7 (10.3%) | |

| Cooperation | 5 (7.4%) | |

| Geographical areas visited | Latin America | 20 (29.4%) |

| Middle East | 12 (17.6%) | |

| Oceania and South-East Asia | 12 (17.6) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 7 (10.3) | |

| North Africa | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Median duration of the trip (in days) | 30 (IQRS 14–96) | |

| Median duration of symptoms (in days) | 30 (IQR 12–120) | |

| Mean number of bowel movements per day | 6 (SD 3.9) | |

| Symptoms onset | During the trip | 49 (72.1%) |

| After the trip | 19 (27,9%) | |

| Clinical picture | Abdominal pain | 46 (32.4%) |

| Fever | 28 (41.2%) | |

| Dysentery | 22 (32.4%) | |

| Nausea | 20 (29.4%) | |

| Vomiting | 14 (20.6%) | |

| Aetiology | Parasitic infection | 24 (35.3%) |

| Bacterial infection | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Mixed infection | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Unknown | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Parasites and protists detected | Giardia duodenalis | 20 (29.4%) |

| Blastocystis spp. | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Bacteria detected | Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli | 3 (4.4%) |

| Enteroinvasive E. coli | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Enterotoxigenic E. coli | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Shigella spp. | 2 (2.9%) | |

| . | n = 68 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 32 (47.1%) |

| Female | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Mean age (in years) | 33 (SD 10.6) | |

| Purpose of the travel | Tourism | 45 (66.2%) |

| VFR | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Work | 7 (10.3%) | |

| Cooperation | 5 (7.4%) | |

| Geographical areas visited | Latin America | 20 (29.4%) |

| Middle East | 12 (17.6%) | |

| Oceania and South-East Asia | 12 (17.6) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 7 (10.3) | |

| North Africa | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Median duration of the trip (in days) | 30 (IQRS 14–96) | |

| Median duration of symptoms (in days) | 30 (IQR 12–120) | |

| Mean number of bowel movements per day | 6 (SD 3.9) | |

| Symptoms onset | During the trip | 49 (72.1%) |

| After the trip | 19 (27,9%) | |

| Clinical picture | Abdominal pain | 46 (32.4%) |

| Fever | 28 (41.2%) | |

| Dysentery | 22 (32.4%) | |

| Nausea | 20 (29.4%) | |

| Vomiting | 14 (20.6%) | |

| Aetiology | Parasitic infection | 24 (35.3%) |

| Bacterial infection | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Mixed infection | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Unknown | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Parasites and protists detected | Giardia duodenalis | 20 (29.4%) |

| Blastocystis spp. | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Bacteria detected | Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli | 3 (4.4%) |

| Enteroinvasive E. coli | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Enterotoxigenic E. coli | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Shigella spp. | 2 (2.9%) | |

| . | n = 68 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 32 (47.1%) |

| Female | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Mean age (in years) | 33 (SD 10.6) | |

| Purpose of the travel | Tourism | 45 (66.2%) |

| VFR | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Work | 7 (10.3%) | |

| Cooperation | 5 (7.4%) | |

| Geographical areas visited | Latin America | 20 (29.4%) |

| Middle East | 12 (17.6%) | |

| Oceania and South-East Asia | 12 (17.6) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 7 (10.3) | |

| North Africa | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (16.2%) | |

| Median duration of the trip (in days) | 30 (IQRS 14–96) | |

| Median duration of symptoms (in days) | 30 (IQR 12–120) | |

| Mean number of bowel movements per day | 6 (SD 3.9) | |

| Symptoms onset | During the trip | 49 (72.1%) |

| After the trip | 19 (27,9%) | |

| Clinical picture | Abdominal pain | 46 (32.4%) |

| Fever | 28 (41.2%) | |

| Dysentery | 22 (32.4%) | |

| Nausea | 20 (29.4%) | |

| Vomiting | 14 (20.6%) | |

| Aetiology | Parasitic infection | 24 (35.3%) |

| Bacterial infection | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Mixed infection | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Unknown | 36 (52.9%) | |

| Parasites and protists detected | Giardia duodenalis | 20 (29.4%) |

| Blastocystis spp. | 6 (8.8%) | |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Bacteria detected | Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli | 3 (4.4%) |

| Enteroinvasive E. coli | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Enterotoxigenic E. coli | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Shigella spp. | 2 (2.9%) | |

In 32 of the 68 (47.1%) patients, an infectious cause of the diarrhoea was detected; 75% (n = 24) were parasitic infections, 18.8% (n = 6) bacterial infections and 6.3% (n = 2) mixed infections. Giardia duodenalis was the most frequently detected parasitic infection (n = 20, 83.3%), followed by Entamoeba histolytica (n = 2, 2.9%). Other frequently detected parasites and protists with an uncertain pathogenic role were Blastocystis spp. (n = 6; 8.8%) and D. fragilis (n = 3; 4.4%). The main bacteria related to TD were enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) (n = 3; 4.4%) and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) (n = 3; 4.4%), followed by enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) (n = 2; 2.9%) and Shigella spp. (n = 2; 2.9%). As regards concomitant infections, both cases detected had G. duodenalis, one co-infected with Shigella spp. and the other with enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC). In 17 out of 68 cases (25%), empirical antibiotic treatment prior to the etiological diagnosis of TD was prescribed. The most commonly used empirical treatment was ciprofloxacin (n = 6; 35.3%) and metronidazole (n = 4; 23.5%). Subsequently, in 44 out of 68 cases (64.7%), targeted antibiotic therapy based on microbiological results was prescribed: tinidazole (n = 20; 45.5%), tinidazole followed by paromomycin sulfate (n = 5; 11.4%), ciprofloxacin (n = 11; 25%), metronidazole (n = 5; 11.4%), amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (n = 2; 4.5%), and albendazole (n = 1; 2.3%). In 7 out of 68 (10.3%) patients without any parasitic or bacterial infection detected, no specific treatment was required due to the early resolution of the symptoms.

Between June and July 2022, 43 of the 68 patients were contacted by telephone and consented to participate in the survey by responding a structured questionnaire. The response rate was 63% (n = 43). The remaining patients (36.8%; n = 25) were missed or could not be reached by telephone (up to three calls). The results are presented in Table 3. The referred mean time of persisting symptoms after TD diagnosis was 15 (SD 13) months. The main symptoms described after the acute TD episode were: a change in the frequency and/or consistency of bowel movements (n = 12; 27.9%), intermittent abdominal pain (n = 11; 25.6%) and flatulence (n = 7; 16.3%). Thirty-one of the 43 patients (72.1%) reported receiving some chronic treatment during the TD episode, mostly antiacids (n = 28; 65.1%) and anxiolytics (n = 4; 9.3%). Most subjects (n = 41; 95.3%), reported an impairment in daily life activities due to their clinical digestive symptoms, this impairment being slight in 11 out of 43 participants (25.6%), moderate in 18 (41.9%) and severe in 12 (27.9%). Seventeen subjects (39.5%) were referred to a gastroenterologist and 20 (46.5%) had an endoscopic examination, 35% of which showed some abnormality: gastritis (n = 2; 10%), ulcerative colitis (n = 2; 10%), diverticulosis (n = 1; 5%), polyposis (n = 1; 5%) and haemorrhoids (n = 1; 5%). An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging was performed in one case revealing severe abdominal endometriosis. Twenty-eight patients (65.1%) followed specific counselling or symptomatic treatment, most via a low-fat diet (n = 21; 75%) or probiotics (n = 9; 32.1%). Of the 43 patients contacted, 17 (39.5%) also referred to persistent fatigue with a mean duration of 6 (SD 13) months after the TD diagnosis.

Characteristics of individuals presenting with PI-IBS responding a questionnaire via a follow-up telephone call

| . | n = 43 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean time of remaining symptoms (in months) | 15 (SD 6–18) | |

| Persistent symptoms | Change in the frequency and/or consistency of bowel movements | 12/43 (27.9%) |

| Intermittent abdominal pain | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Flatulence | 7/43 (16.3%) | |

| Concomitant chronic treatment | Yes | 31/43 (72.1%) |

| No | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Impairment in activities of daily living | No | 2/43 (4.7%) |

| Slight | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Moderate | 18/43 (41.9%) | |

| Severe | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Gastroenterologist evaluation | Yes | 17/43 (39.5%) |

| No | 26/43 (60.5%) | |

| Endoscopic examination performed | Yes | 20/43 (46.5%) |

| No | 23/43 (53.5%) | |

| Abnormalities upon endoscopic examination | No abnormalities | 13/20 (65%) |

| Gastritis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Diverticulosis | 1(20) (5%) | |

| Polyposis | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Haemorrhoids | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Specific counselling of symptomatic treatment | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New trips | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New diagnosis of TD after the new trip | Yes | 6/28 (21.4%) |

| No | 22/28 (78.6%) | |

| Risk score for PI-IBS | Low | 10/43 (23.8%) |

| Moderate | 29/43 (69%) | |

| High | 3/43 (7.1%) | |

| . | n = 43 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean time of remaining symptoms (in months) | 15 (SD 6–18) | |

| Persistent symptoms | Change in the frequency and/or consistency of bowel movements | 12/43 (27.9%) |

| Intermittent abdominal pain | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Flatulence | 7/43 (16.3%) | |

| Concomitant chronic treatment | Yes | 31/43 (72.1%) |

| No | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Impairment in activities of daily living | No | 2/43 (4.7%) |

| Slight | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Moderate | 18/43 (41.9%) | |

| Severe | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Gastroenterologist evaluation | Yes | 17/43 (39.5%) |

| No | 26/43 (60.5%) | |

| Endoscopic examination performed | Yes | 20/43 (46.5%) |

| No | 23/43 (53.5%) | |

| Abnormalities upon endoscopic examination | No abnormalities | 13/20 (65%) |

| Gastritis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Diverticulosis | 1(20) (5%) | |

| Polyposis | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Haemorrhoids | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Specific counselling of symptomatic treatment | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New trips | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New diagnosis of TD after the new trip | Yes | 6/28 (21.4%) |

| No | 22/28 (78.6%) | |

| Risk score for PI-IBS | Low | 10/43 (23.8%) |

| Moderate | 29/43 (69%) | |

| High | 3/43 (7.1%) | |

Characteristics of individuals presenting with PI-IBS responding a questionnaire via a follow-up telephone call

| . | n = 43 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean time of remaining symptoms (in months) | 15 (SD 6–18) | |

| Persistent symptoms | Change in the frequency and/or consistency of bowel movements | 12/43 (27.9%) |

| Intermittent abdominal pain | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Flatulence | 7/43 (16.3%) | |

| Concomitant chronic treatment | Yes | 31/43 (72.1%) |

| No | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Impairment in activities of daily living | No | 2/43 (4.7%) |

| Slight | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Moderate | 18/43 (41.9%) | |

| Severe | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Gastroenterologist evaluation | Yes | 17/43 (39.5%) |

| No | 26/43 (60.5%) | |

| Endoscopic examination performed | Yes | 20/43 (46.5%) |

| No | 23/43 (53.5%) | |

| Abnormalities upon endoscopic examination | No abnormalities | 13/20 (65%) |

| Gastritis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Diverticulosis | 1(20) (5%) | |

| Polyposis | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Haemorrhoids | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Specific counselling of symptomatic treatment | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New trips | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New diagnosis of TD after the new trip | Yes | 6/28 (21.4%) |

| No | 22/28 (78.6%) | |

| Risk score for PI-IBS | Low | 10/43 (23.8%) |

| Moderate | 29/43 (69%) | |

| High | 3/43 (7.1%) | |

| . | n = 43 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean time of remaining symptoms (in months) | 15 (SD 6–18) | |

| Persistent symptoms | Change in the frequency and/or consistency of bowel movements | 12/43 (27.9%) |

| Intermittent abdominal pain | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Flatulence | 7/43 (16.3%) | |

| Concomitant chronic treatment | Yes | 31/43 (72.1%) |

| No | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Impairment in activities of daily living | No | 2/43 (4.7%) |

| Slight | 11/43 (25.6%) | |

| Moderate | 18/43 (41.9%) | |

| Severe | 12/43 (27.9%) | |

| Gastroenterologist evaluation | Yes | 17/43 (39.5%) |

| No | 26/43 (60.5%) | |

| Endoscopic examination performed | Yes | 20/43 (46.5%) |

| No | 23/43 (53.5%) | |

| Abnormalities upon endoscopic examination | No abnormalities | 13/20 (65%) |

| Gastritis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2/20 (10%) | |

| Diverticulosis | 1(20) (5%) | |

| Polyposis | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Haemorrhoids | 1/20 (5%) | |

| Specific counselling of symptomatic treatment | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New trips | Yes | 28/43 (65.1%) |

| No | 15/43 (34.9%) | |

| New diagnosis of TD after the new trip | Yes | 6/28 (21.4%) |

| No | 22/28 (78.6%) | |

| Risk score for PI-IBS | Low | 10/43 (23.8%) |

| Moderate | 29/43 (69%) | |

| High | 3/43 (7.1%) | |

Twenty-eight (65.1%) of the subjects reported new trips to tropical or subtropical areas after presenting symptoms; six (21.4%) were diagnosed with TD again after one of these trips. Regarding the risk of developing PI-IBS at the time of diagnosis of AGE, 32 of the 43 (76.1%) participants presented a moderate-high risk according to the questionnaire performed at the time of the telephone interview.

In terms of factors associated with the development of PI-IBS, the multivariate analysis revealed that parasitic infections were independent risk factors for PI-IBS (OR 3.0, 95%CI 1.2–7.8). On the other hand, pre-travel counselling reduced the risk of PI-IBS (OR 0.4, 95%CI 0.2–0.9) (Table 4).

| . | Patients with post-infectious syndrome (n = 68) . | Patients without post-infectious syndrome (n = 567) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis P-value, (OR, 95%CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male Age > 35 years old Latin American destination Duration of trip > 23 days Pre-travel advice Duration of TD > 15 days Number of bowel movements > 6 Presence of dysentery Presence of fever Parasitic aetiology | 36/68 (52.9%) 29/68 (42.6%) 20/57 (35.1%) 38/68 (55.9%) 26/68 (38.2%) 37/51 (72.5%) 17/44 (38.6%) 22/68 (32.3%) 28/68 (41.2%) 20/27 (74.1%) | 336/567 (59.3%) 248/567 (43.7%) 147/505 (29.1%) 278/560 (49.6%) 292/567 (51.5%) 218/460 (47.4%) 118/315 (37.5%) 144/567 (25.4%) 258/567 (45.5%) 122/224 (54.5%) | 0.318 0.864 0.349 0.331 0.039 <0.001 0.880 0.217 0.498 0.052 | 0.049 (OR 0.4, 95%CI 0.2–0.9) 0.557 (OR 0.7, 95%CI 0.3–1.8) 0.447 (OR 1.4, 95%CI 0.6–3.4) 0.022 (OR 3.0, 95%CI 1.2–7.8) |

| . | Patients with post-infectious syndrome (n = 68) . | Patients without post-infectious syndrome (n = 567) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis P-value, (OR, 95%CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male Age > 35 years old Latin American destination Duration of trip > 23 days Pre-travel advice Duration of TD > 15 days Number of bowel movements > 6 Presence of dysentery Presence of fever Parasitic aetiology | 36/68 (52.9%) 29/68 (42.6%) 20/57 (35.1%) 38/68 (55.9%) 26/68 (38.2%) 37/51 (72.5%) 17/44 (38.6%) 22/68 (32.3%) 28/68 (41.2%) 20/27 (74.1%) | 336/567 (59.3%) 248/567 (43.7%) 147/505 (29.1%) 278/560 (49.6%) 292/567 (51.5%) 218/460 (47.4%) 118/315 (37.5%) 144/567 (25.4%) 258/567 (45.5%) 122/224 (54.5%) | 0.318 0.864 0.349 0.331 0.039 <0.001 0.880 0.217 0.498 0.052 | 0.049 (OR 0.4, 95%CI 0.2–0.9) 0.557 (OR 0.7, 95%CI 0.3–1.8) 0.447 (OR 1.4, 95%CI 0.6–3.4) 0.022 (OR 3.0, 95%CI 1.2–7.8) |

| . | Patients with post-infectious syndrome (n = 68) . | Patients without post-infectious syndrome (n = 567) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis P-value, (OR, 95%CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male Age > 35 years old Latin American destination Duration of trip > 23 days Pre-travel advice Duration of TD > 15 days Number of bowel movements > 6 Presence of dysentery Presence of fever Parasitic aetiology | 36/68 (52.9%) 29/68 (42.6%) 20/57 (35.1%) 38/68 (55.9%) 26/68 (38.2%) 37/51 (72.5%) 17/44 (38.6%) 22/68 (32.3%) 28/68 (41.2%) 20/27 (74.1%) | 336/567 (59.3%) 248/567 (43.7%) 147/505 (29.1%) 278/560 (49.6%) 292/567 (51.5%) 218/460 (47.4%) 118/315 (37.5%) 144/567 (25.4%) 258/567 (45.5%) 122/224 (54.5%) | 0.318 0.864 0.349 0.331 0.039 <0.001 0.880 0.217 0.498 0.052 | 0.049 (OR 0.4, 95%CI 0.2–0.9) 0.557 (OR 0.7, 95%CI 0.3–1.8) 0.447 (OR 1.4, 95%CI 0.6–3.4) 0.022 (OR 3.0, 95%CI 1.2–7.8) |

| . | Patients with post-infectious syndrome (n = 68) . | Patients without post-infectious syndrome (n = 567) . | Univariate analysis (P-value) . | Multivariate analysis P-value, (OR, 95%CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male Age > 35 years old Latin American destination Duration of trip > 23 days Pre-travel advice Duration of TD > 15 days Number of bowel movements > 6 Presence of dysentery Presence of fever Parasitic aetiology | 36/68 (52.9%) 29/68 (42.6%) 20/57 (35.1%) 38/68 (55.9%) 26/68 (38.2%) 37/51 (72.5%) 17/44 (38.6%) 22/68 (32.3%) 28/68 (41.2%) 20/27 (74.1%) | 336/567 (59.3%) 248/567 (43.7%) 147/505 (29.1%) 278/560 (49.6%) 292/567 (51.5%) 218/460 (47.4%) 118/315 (37.5%) 144/567 (25.4%) 258/567 (45.5%) 122/224 (54.5%) | 0.318 0.864 0.349 0.331 0.039 <0.001 0.880 0.217 0.498 0.052 | 0.049 (OR 0.4, 95%CI 0.2–0.9) 0.557 (OR 0.7, 95%CI 0.3–1.8) 0.447 (OR 1.4, 95%CI 0.6–3.4) 0.022 (OR 3.0, 95%CI 1.2–7.8) |

Discussion

In our cohort of patients with a diagnosis of TD, the occurrence of PI-IBS was 10%, which is in line with previous studies.10 Herein, we describe 68 adult patients with PI-IBS, most of them young women, who presented prolonged symptomatology during the acute TD episode, with symptoms suggestive of PI-IBS persisting for more than 6 months and fulfilling two Rome IV criteria. Along this line, it is important to remark that there are differences in PI-IBS prevalence between the Rome III and Rome IV criteria as changes in Rome IV criteria made them more restrictive, excluding some of the individuals diagnosed with IBS by Rome III. Moreover, the prevalence rates for PI-IBS are much lower with Rome IV; however, disease severity is higher in patients diagnosed via Rome IV than via Rome III.19–21,26 There were two major changes in Rome IV criteria: the removal of the term ‘discomfort’ replaced by ‘pain or discomfort’ and the change of symptom frequency for pain from two/three times per month (Rome III) to at least weekly (Rome IV).26 The present study was designed and performed after 2016, when the Rome IV criteria had already been established, so the impact in terms of prevalence comparing studies performed before 2016 could be lower.

PI-IBS may be preceded by bacterial,11,27 parasite-induced gastroenteritis4,15 or even a viral infection, including norovirus and rotavirus.28,29 In this context, TD and PI-IBS are generally infectious in origin, but pathogens could not be identified in up to 50% of TD cases. It is possible that some of these pathogens were misdiagnosed due to low diagnostic sensitivity and inadequate investigations.30,31 SARS-CoV-2 could also cause gastrointestinal symptoms and diarrhoea in some travellers, although it seems to be less frequent with the more recent viral variants. In rare situations, diseases of uncertain aetiology that are presumed to be infectious can cause gastrointestinal disorders in travellers, including Brainerd’s diarrhoea and tropical sprue. Other causes classified as non-infectious include colorectal cancer, non-biological contaminants in food and water, drugs or laxative overuse.32 In our cohort, parasitic infection was the most frequently detected aetiology within the group with a TD diagnosis, and the rate of detection could be higher as molecular methods for protozoa detection in stool have recently been introduced.33 Among them, G. duodenalis was the most commonly identified parasite, in accordance with previous studies reporting prolonged post-infectious gastrointestinal manifestations.4,34

Giardia duodenalis is a non-invasive microorganism and there is limited information about its disease-causing mechanisms and physiopathology.35 This parasite has a worldwide distribution, although more prevalent in warm climates, and usually infects the upper small intestine causing acute diarrhoea in 280 million people every year. Most patients experience acute symptoms such as diarrhoea, nausea, abdominal pain or vomiting, which usually resolve within 7–10 days after onset. Others patients, such as immunocompromised hosts, may suffer from a long-lasting disease that becomes very difficult to manage;36 however, in our cohort, there were no immunosuppressed travellers diagnosed with PI-IBS. Giardia infections can even be found in medium-to-high-income countries such as Spain, but this could be an exceptional situation.37

Recommended first-line therapy for giardiasis includes nitroimidazole antiprotozoal agents such as tinidazole or metronidazole; however, a growing number of nitroimidazole-refractory giardiasis are being reported and an effective second-line treatment strategy has yet to be determined.38 In our study, and similar to some Giardia outbreaks described in a non-endemic area, all patients referred long-term symptoms after the parasite was cleared,39 the most frequently referred symptoms being changes in stool consistency and the number of stool movements per day, intermittent abdominal pain and flatulence. Similarly, fatigue was also reported to persist after acute infection in almost half of the patients but, as described in other studies, it disappeared along with the other symptoms.4

The general pathophysiology of PI-IBS is only partially understood and different factors have been considered relevant. The main research focuses on alterations in gastrointestinal motility, apart from microbiological identifications.40 Alterations in gut permeability and chronic bowel inflammation due to post-infectious neuroplastic changes have been described as the most important mechanisms of PI-IBS, although its development is most likely to be multifactorial.40,41 Other mechanisms explored so far include disorders of the gut-brain axis, diet, genetic factors, changes in the intestinal microbiota, mucosal inflammation and also alterations in intestinal permeability or brain function.41 As antiacids and anxiolytics were commonly prescribed prior to the PI-IBS diagnosis in our cohort, it is important to highlight the controversial association with an increased risk of TD of gastric acid-suppressing drugs, histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors.42 At the same time, stress, life experiences, abnormalities in immune response or serotonin metabolism, and patients with anxiety disorders could also be at increased risk of PI-IBS after AGE.43

Complementary studies performed in our cohort showed an alternative cause of the persisting gastrointestinal symptoms in some patients, highlighting ulcerative colitis. This fact stresses the importance of performing a complete diagnostic approach in all suspected cases of PI-IBS to rule out other life-threatening and manageable gastrointestinal diseases.

The ideal approach for patients with PI-IBS proposed in the literature emphasizes obtaining new samples for stool cultures for bacterial pathogens, ova and parasites to investigate antibiotic resistance and confirm whether the infection has been cleared, as in most PI-IBS cases, stool cultures after treatment remain negative. Blood count and C-reactive protein are also important to monitor the systemic impact of the disorder.44 However, PI-IBS may present as a spectrum of manifestations, not always completely fitting within the frame of the Rome IV criteria. The data obtained in our study highlight the importance of creating new protocols for a thorough investigation of other causes with similar clinical manifestations, as described in the literature.45 In this way, the diagnosis behind persistent symptoms in our cohort was consistent with the differential diagnosis suggested by some authors, including acquired primary hypolactasia, gastroenteritis, bile acid malabsorption, inflammatory bowel disease or lymphocytic colitis but also alterations in the thyroid gland and celiac disease.33,46,47 From a social perspective, almost all participants in our structured survey reported great physical and psychological stress. Previous research has shown a significant impairment of health-related quality of life, work productivity, daily activities and the emotional well-being of patients suffering from PI-IBS.48 In fact, in the present study, more than a quarter of patients referred to a significant impact on their quality of life. In addition, although our survey was not designed to capture economic data, PI-IBS may involve high indirect costs for patients.49

In this study, more than three-quarters of the patients presented with a moderate-high risk of developing PI-IBS at the time of TD diagnosis according to the questionnaire for AGE.25 At the same time, receiving pre-travel counselling proved to be a protective factor; a thorough pre-travel evaluation to provide appropriate guidance and information is critical to protect travellers. Not many vaccines are currently licenced for TD prevention and those against ETEC, Shigella spp. and C. jejuni are under development. Only a cholera vaccine, which provides a short immunization against ETEC, can be found in Canada and Europe.50 According to these results, the application of a structured questionnaire to stratify patients according to their risk of developing PI-IBS and promoting the importance of a pre-travel visit might be a great tool for the prevention and control of this disorder. Similarly, a longer follow up of those patients presenting moderate or high risk according to the questionnaire should be considered. Pre-travel counselling includes all types of information to ensure health and safety despite the risks that travellers might be exposed to, including hand hygiene recommendations and food and water precautions to reduce the risk of TD. This counselling is consequently one of the most important preventive actions, although a lack of perceived risk by travellers can be the major barrier to seeking and adhering to travel-related recommendations.51 All these findings suggest the current need for therapists to effectively prevent, diagnose, treat and alleviate the considerable burden of this frequent condition.24,52

This study has some limitations, most of them derived from its retrospective nature. Most of the information was retrieved from medical records, and different physicians were involved. The International Health Unit Vall d’Hebron-Drassanes is a referral centre and a selection bias could also arise in this context, as severe TD might be the only cases attending the unit. Moreover, not all patients could be contacted by telephone to collect the remaining information for follow-up and, for those who answered the telephone call, memory bias could also be an important factor as it increases along with the time between the interview and the initial event.

In summary, PI-IBS is a relatively common complication of TD. It could be up to three times more frequent after parasitic TD. While the epidemiology and natural history of PI-IBS have been well characterized, to date, knowledge of its pathophysiology as well as the most important associated factors remains limited. Furthermore, the use of standardized tools to evaluate the risk of persistent symptoms may help clinicians offer a tailored follow-up for patients with TD. More information regarding PI-IBS and further investigation into risk factors will have an impact on improving action protocols for action and prevention, reducing morbidity and improving its evolution.

Funding

A.S.-M. is supported by a Juan Rodés (JR18/00022) postdoctoral fellowship from ISCIII. The other authors did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributions

S.E.C., F.S., I.O. and I.M. conceived the study, collected the data, performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; L.G., E.S. and V.R. performed the laboratory tests; B.T., A.S.M., N.S.D., M.L.A., P.B.N., J.E.P. and D.P. collected the data; all authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT author Statement

Sergio España-Cueto (Conceptualization-Equal, Data curation-Equal, Formal analysis-Equal, Writing—original draft-Equal), Ines Oliveira (Conceptualization-Equal, Data curation-Equal, Formal analysis-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Writing—original draft-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Fernando Salvador (Conceptualization-Equal, Data curation-Equal, Formal analysis-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Writing—original draft-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Lidia Goterris (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Begoña Treviño (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Adrian Sanchez (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Núria Serre-Delcor (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Elena Sulleiro (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Virginia Rodríguez (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Maria Luisa Aznar (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Pau Bosch-Nicolau (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Juan Espinosa-Pereiro (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal), Diana Pou (Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal) and Israel Molina (Conceptualization-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Writing—review & editing-Equal)

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.