-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Eiichiro Sando, Konosuke Morimoto, Shinji Narukawa, Katsumi Nakata, COVID-19 outbreak on the Costa Atlantica cruise ship: use of a remote health monitoring system, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 2, March 2021, taaa163, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa163

Close - Share Icon Share

The second outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on a cruise ship in Japan occurred on the Costa Atlantica, which was at anchor in Nagasaki for repairs.1 No passengers were aboard. We considered disembarking all 624 crew members and then monitoring their health status because isolation is difficult inside the ship owing to the demands of essential work. In addition, the medical resources onboard the ship were limited: the ship’s doctor and two nurses were insufficient to monitor the symptoms of all the crew members. However, there were no available accommodations for the crew members. Each non-essential crew member had to be isolated in a passenger cabin, and we decided to provide support from outside the ship to minimize the chance of infection in medical support staff. Therefore, a remote health monitoring system was needed.

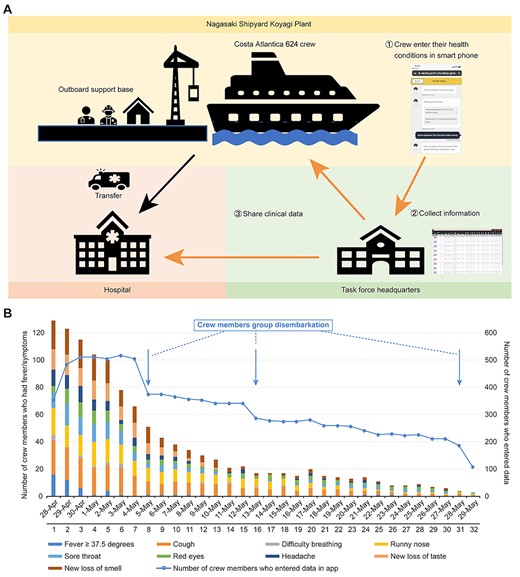

Using a smartphone, each crew member entered their health status into a browser-based system, including their age, sex, underlying diseases, smoking history, height and weight; the system was accessed by scanning a 2D bar code. In addition, we requested that the crew members self-report their body temperature and any symptoms, such as coughing, difficulty breathing, runny nose, sore throat, red eyes, headache and new loss of taste/smell, each day. We considered a body temperature ≥37.5°C to be a fever. We collected the information shared with the ship’s medical centre and the supporting medical staff twice a day (Figure 1A) and used it to help the ship’s doctor examine patients, perform computed tomography scans and triage crew members needing transportation to a hospital.

Remote health monitoring in Nagasaki. (A) Health monitoring system; and

(B) number of crew members who had symptoms. (A) shows the remote health monitoring system, which was accessed via a smartphone. Crew members reported their own health status via smartphone. The information was collected in the task force headquarters and shared with the ship medical centre and medical support staff twice per day. (B) shows a combined bar and line graph. The first axis for the bar graph shows the cumulative number of crew members who reported each symptom, including a fever ≥37.5°C. The second axis for the line graph shows the changes in the number of crew members who entered the data. Some crew members disembarked in groups. The crew members were disembarked sequentially, with priority given to those who were negative for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 by loop-mediated isothermal amplification/polymerase chain reaction and symptom free.

Excluding one nurse who boarded the ship on 26 April, the remaining 623 crew members were tested for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 by loop-mediated isothermal amplification or polymerase chain reaction from 21–25 April, and 148 were positive. One additional COVID-19 case was confirmed on 3 May. A total of 95.2% (594/624) of the crew entered their health data at least once, and an average of 83.2% of the crew reported their symptoms each day from 28 April to 29 May. Of these, 23.7% (141/594) of the crew complained of any of the relevant symptoms, including fever. In the early phase of monitoring, the most commonly reported symptom was a cough, followed by a runny nose and a new loss of smell (Figure 1B). The actual number of crew members who reported any symptoms decreased from 78 on 28 April to 29 on 5 May and 13 on 12 May, as shown in the daily cumulative number of affected crew members in the figure. Twice per day, we discussed with the medical staff about the crew members’ health statuses and the need for transportation of crew members to the hospital. We transferred 11 crew members to the hospital without delay, including six COVID-19 patients with pneumonia, and no crew members died.

In contrast to the first COVID-19 outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan,2 we monitored all crew members’ health statuses remotely without the disembarkation of asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 patients. This remote monitoring allowed us to minimize the activity of support staff onboard the ship and prevented their infection. The early detection of infection outbreaks by monitoring is crucial, and this remote monitoring system would also be useful in other settings, including nursing care facilities and home care situations.

Authors’ Contributions

E.S. contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, figures and writing of the manuscript. S.N. contributed to the system development, data collection, data analysis and writing of the manuscript. K.M. and K.N. contributed to supervising the study and writing the manuscript.

Funding

The browser-based system was jointly developed by Fujitsu Limited and E.S., who is not a member of the Nagasaki Prefecture Government, and was provided free of charge to Nagasaki Prefecture by Fujitsu Limited.

Conflict of Interest

S.N. is an employee of Fujitsu Limited. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest. E.S. received no rewards from Fujitsu Limited.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the support team members and all the staff and crew members of the Costa Atlantica. The support team members included Yuzo Kurose and Yuka Mori from Fujitsu Limited; Takeshi Tanaka, Masato Tashiro, Koichi Izumikawa, Hayato Takayama, Nobuyuki Kawachi, Haruka Maeda, Ikkoh Yasuda and Michiko Toizumi from Nagasaki University; Rie Fujita and Maiko Hasegawa from Nagasaki Prefectural Government; Katsuaki Motomura from Nagasaki City Public Health Center; Yuzo Arima, Tomoe Shimada and Motoi Suzuki from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases; and Yoshitaka Kohayagawa from the National Hospital Organization.