-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kapil Goel, Arunima Sen, Prakasini Satapathy, Pawan Kumar, Arun Kumar Aggarwal, Ranjit Sah, Bijaya Kumar Padhi, Human rabies control in the era of post-COVID-19: a call for action, Journal of Travel Medicine, 2023;, taad009, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taad009

Close - Share Icon Share

Human rabies control in the era of post-COVID-19: a call for action

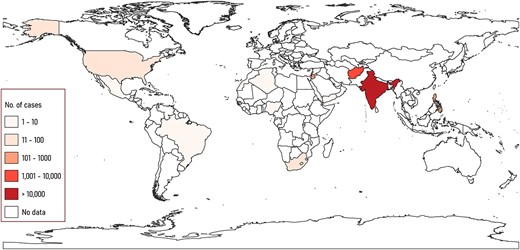

Following the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been a sharp increase in rabies cases and deaths worldwide (Figure 1)1–3 Human rabies cases have resurfaced after 44 years in Brazil, four years in Bhutan, and a long time in Lebanon.4 In 2022, various countries, such as Afghanistan, Jordan, Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka and the USA, witnessed deaths caused by rabies (Table 1). India also reported a substantial number of deaths due to the disease in the same year.3,5 The number of dog bite cases has also increased with reports of a more aggressive nature of stray dogs after the pandemic,6,7 Pet dog abandonment, decreased human–dog contact, and starvation of street dogs during lockdown has added to the stray dog menace. Multiple disruptions in Rabies control occurred during the pandemic, significantly affecting lower income countries.7 Along with limited access to post-exposure treatment due to the closure of dedicated bite centres, there were delays in human and dog vaccine procurement due to international shortages. In Yemen, a scarcity of vaccines was reported even in private hospitals.7 In Zambia, where the vaccine was manufactured locally, production was stopped due to financial constraints.6 Rabies control activities such as mass dog vaccination and animal birth control took a backseat due to budget cuts. Very few countries carried out the process without hindrance.

Choropleth map showing global outbreak of dog-bite cases between January and October 2022, as reported at ProMED news (https://isid.org). The map was created using QGIS 3.26.3. The base layer map was used from the ArcGIS Hub.

Disease epidemiology

Zoonotic viral disease is endemic in most developing countries. Every year, dog-mediated rabies kills an estimated 59 000 individuals costing 8.6 billion US$ per year as per the World Health Organization (WHO). Most cases are from Asia and Africa, disproportionately affecting the poor and vulnerable communities. Around 40% of deaths occur among children under 15 years of age. An increase in animal-bite cases and related deaths have been reported worldwide. The disease is re-emerging in some areas where rabies has not been reported in a long time. In India, the disease is widespread in all the states and union territories (UTs), except in Lakshadweep, Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The actual burden of Rabies in India is unknown. According to WHO, an estimated 35% of rabies deaths occur in India annually. However, the number varies significantly from the 6644 clinically suspected rabies cases and deaths reported by the National Rabies Control Program in the last ten years. The incubation period of the zoonotic disease generally varies between two to three months; it could be shorter or longer, depending upon the location of virus entry and the viral load. Transmission occurs after being bitten or scratched by a rabid animal. While dogs are still responsible for most outbreaks, bat bites are also a concern. It is rare but possible to get infected from non-bite exposures if human mucosa or fresh skin wounds come into direct contact with the saliva of infected animals. The initial symptoms of the disease include fever, pain and paraesthesia at the wound site. As the disease progresses, brain and spinal cord inflammation develops, characterized by behavioural abnormalities, hallucinations, delirium, hydrophobia (fear of water) and insomnia, eventually resulting in death. The disease has two forms, furious rabies, in which death occurs after a few days, and paralytic disease, which has a less dramatic, more prolonged course.

| Country . | Deaths . |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 10 |

| Algeria | 1 |

| Brazil | 5 |

| India | 63 |

| Israel | 0 |

| Jordan | 1 |

| Lebanon | 2 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 |

| Nepal | 1 |

| Nigeria | 0 |

| Philippines | 222 |

| South Africa | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 12 |

| Tunisia | 0 |

| USA | 0 |

| Yemen | 2 |

| Country . | Deaths . |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 10 |

| Algeria | 1 |

| Brazil | 5 |

| India | 63 |

| Israel | 0 |

| Jordan | 1 |

| Lebanon | 2 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 |

| Nepal | 1 |

| Nigeria | 0 |

| Philippines | 222 |

| South Africa | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 12 |

| Tunisia | 0 |

| USA | 0 |

| Yemen | 2 |

Source: ProMED, Outbreak News Today https://promedmail.org/in-the-news/

| Country . | Deaths . |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 10 |

| Algeria | 1 |

| Brazil | 5 |

| India | 63 |

| Israel | 0 |

| Jordan | 1 |

| Lebanon | 2 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 |

| Nepal | 1 |

| Nigeria | 0 |

| Philippines | 222 |

| South Africa | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 12 |

| Tunisia | 0 |

| USA | 0 |

| Yemen | 2 |

| Country . | Deaths . |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 10 |

| Algeria | 1 |

| Brazil | 5 |

| India | 63 |

| Israel | 0 |

| Jordan | 1 |

| Lebanon | 2 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 |

| Nepal | 1 |

| Nigeria | 0 |

| Philippines | 222 |

| South Africa | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 12 |

| Tunisia | 0 |

| USA | 0 |

| Yemen | 2 |

Source: ProMED, Outbreak News Today https://promedmail.org/in-the-news/

Prevention and control

Although highly lethal, rabies is preventable. The ‘One Health’ approach conceptualizes that human and animal health is interconnected with each other and their shared environment.8 It focuses on collaborative problem solving through intersectoral coordination at the local, national, and global levels. India and many other countries have adopted this model to work toward disease elimination. The core strategies include tackling the disease at its source through mass dog vaccination programs, increasing access to affordable post-exposure prophylaxis and biologicals, improved rabies awareness and education, and strong human and canine rabies surveillance.

Mass vaccination programmes

Focusing solely on animal bite victims has no impact on the burden of rabies in the canine population, leaving other community members vulnerable to the disease. Immunization of 70% of dogs can stop rabies transmission in high-risk areas. In regions where the number of free-roaming dogs is high, capturing dogs can require advanced strategies such as using specialized tools, net-catching or oral bait handouts. Oral rabies vaccination (ORV) of dogs in combination with parenteral approaches makes it possible to intensively vaccinate dog populations in a short time that would otherwise be unreachable.9 Utilizing smartphone applications to geographically direct vaccination teams at the community level can significantly speed the virus elimination by improving vaccine coverage and reducing pockets of the unvaccinated population.

Increasing access to affordable post-exposure prophylaxis and biologicals

The timely delivery of the intervention is almost 100% effective in preventing deaths. However, the post-exposure prophylaxis (wound treatment) is not available in many endemic areas.7 Most deaths from rabies occur due to inappropriate treatment following exposure to an infected animal. Deep wounds in areas rich in nerve supply, multiple wounds, and bites on the head or neck facilitate virus entry. Wound management is an essential aspect of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). The rabies virus is present in high concentrations in the rabid animal’s saliva; hence, the wound must be cleaned using soap and water for at least 15 minutes to decrease the viral load. Improper wound management, failure to seek prompt treatment, and unavailability of biologics at the health centre provide ample time for the virus to spread. Not following the proper protocol, improper vaccine/immunoglobulin administration, and missed wounds may lead to rabies despite vaccination. Cases of low-quality or counterfeit vaccines have also been reported. Every animal bite should be considered a potentially rabid animal bite, and treatment should begin immediately per the standard operating procedure. Three-visit PEP rather than four-visit PEP, intradermal vaccinations rather than intramuscular vaccines, and administration of RIG solely to the wound are more cost-effective.

Surveillance: human and canine rabies

Human rabies surveillance involves monitoring animal bite and rabies cases in the community, reporting suspected and confirmed rabies deaths, and evaluating anti-rabies vaccine and serum coverage. The ability to detect and diagnose canine rabies must be improved to understand the scope, track the results of dog vaccination campaigns and remove rabid animals. A GIS-enabled electronic monitoring system, rabies hotline and dedicated reporting portal are particularly effective in eliciting reports of suspected rabies cases from the public, animal welfare and health sectors,10,11

Awareness and education

To reduce mortality among humans, communities must be actively involved. Education initiatives in schools that aim to raise awareness about rabies among youngsters are effective. When schools were closed during the lockdown, rabies awareness campaigns were hampered, and when public events moved online, they could not reach the most marginalized communities.2,6

Imported rabies

Asia has the highest animal exposure among travellers, with India among the top five countries. In 12 years, the number of travellers seeking PEP was 22 and 12 times higher than those who contracted hepatitis A or typhoid.2 Exacerbating the potential risk of rabies, less than one in five travellers with possible exposure practiced proper first aid, and many delayed PEP until they were back.2 Imported rabies in travellers and pets have been reported in non-endemic countries.12 While increasing rabies awareness among travellers will help them avoid rabies exposures and educate them regarding PEP, for a subset of travellers at high risk of exposure, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) eliminates the need for rabies immunoglobulin and reduces the PEP vaccine schedule to two vaccine booster doses instead of four.13 The simplified two doses PrEP regimen further eases its use in last-minute travellers.13 International opinions regarding which travellers should receive PrEP vary tremendously. The evidence-based risk scoring system,10 and the country classification database based on the burden of rabies, the capacity to monitor and the accessibility of biologicals11 will help clinicians in deciding the need for PrEP among travellers and prevent cross-border importation of canine rabies.

Conclusion

Rabies outbreaks are being reported from all over the world, including countries such as Afghanistan, India, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, the Philippines and South Africa. Countries need to develop specific action plans to be considered ‘rabies free’ according to ‘Zero by 30: The Global Strategic Plan to Prevent Human Deaths from Dog-Transmitted Rabies by 2030’. Neglecting the disease and then taking extreme measures like mass killing dogs and other animals is not the solution. Although it is a notifiable disease, rabies in the animal and human populations remains underreported. Quality canine and human rabies data through systemic data collection are required to evaluate national rabies control programs. Countries must actively participate in generating rabies surveillance data at an international level to assess progress toward achieving the global goal. The recent spike in rabies cases in India and other countries highlights the need to tackle the disease through a ‘one health approach’. The human and animal health sectors must collaborate to eliminate the disease through effective resource management and the timely provision of high-quality post-exposure prophylaxis including wound management. Rabies will continue to threaten humans if the infection exists among animals, especially dogs.

Funding

None.

Authors’ contribution

P.S., K.G. and B.K.P. conceptualized the study. A.S. and P.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. P.K. curated the data and prepared the choropleth map using GIS. A.K.A. and R.S. provided critical comments and edited the first draft. All authors reviewed subsequent versions and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in https://isid.org/.

References

Author notes

Kapil Goel, Arunima Sen and Prakasini Satapathy Contributed equally as the first author