-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mette Bøymo Kaarbø, Kristine Grimen Danielsen, Gro Killi Haugstad, Anne Lise Ording Helgesen, Slawomir Wojniusz, The Tampon Test as a Primary Outcome Measure in Provoked Vestibulodynia: A Mixed Methods Study, The Journal of Sexual Medicine, Volume 18, Issue 6, June 2021, Pages 1083–1091, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.03.010

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) is characterized by severe pain, often induced by penetrative sex. This may lead to women abstaining from sexual intercourse, hence the recording of pain intensity levels in PVD research is often challenging. The standardized tampon test was designed as an alternative outcome measure to sexual intercourse pain and has frequently been used in clinical studies.

The aim of this mixed methods study is to evaluate the tampon test as a primary outcome measure for an upcoming randomized clinical trial for women with PVD.

An explanatory sequential design was applied, integrating quantitative and qualitative methods. In phase one, pain intensity levels were evaluated with the tampon test amongst 10 women, aged 18-33, with PVD. The test was repeated on day 1, 7 and 14. Pain intensity was rated on the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), (0-10), 10 being worst possible pain. In phase two, the participants’ experiences with the test were explored with semi-structured interviews using a descriptive and inductive qualitative design. All participants were recruited from the Vulva Clinic, Oslo University Hospital, Norway.

The tampon test data and interviews were brought together to see how the interviews could refine and help to explain the quantitative findings.

The tampon test data demonstrated large intra- and inter-individual variability. Median tampon pain intensity was 4.5 (min=1.7; max=10; Q1=2.5; Q3=6). Many experienced the test as an inadequate representation of pain during intercourse as it was less painful, different in nature and conducted in an entirely different context. Four participants had a mean score of four or lower on the NRS, whilst concurrently reporting high levels of pain during sexual intercourse.

The findings indicate that the tampon test may underestimate severity of pain among some women with PVD. Participants with low pain scores would be excluded from studies where the tampon test is part of the trial eligibility criteria, even though severe pain was experienced during sexual intercourse. Large intra-individual variability in pain scores also reduces the test’s ability to register clinical meaningful changes and hence necessitates repeated measurements per assessment time point.

Although the tampon test has many advantages, this study indicates several potential problems with the application of the test as a primary outcome measure in PVD. In our opinion the test is most useful as a secondary outcome, preferably undertaken repeatedly in order to increase precision of the pain estimation.

INTRODUCTION

Pain is a highly subjective phenomenon, modulated by social context, previous experience of pain, as well as psychological and biological factors. Due to its multifaceted and subjective nature estimating pain in a reliable and valid way is difficult, both in clinical practice and in research. This is especially the case in provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) which is a prevalent, but undertreated long lasting vulvar pain condition, representing the most common cause of painful intercourse.1,2

In PVD research, pain measurements are particularly challenging since pain is experienced upon provocation in a specific context, such as during sexual intercourse. In addition, some women may not engage in penetrative intercourse due to the lack of a partner, fear of pain, or previous medical recommendations.3 Consequently, using intercourse pain as a primary outcome measure may be a challenge for recruitment, but also for data analysis and generalization of results.4 An alternative method is to use the vulvalgesiometer or the tampon test as an outcome measure. The vulvalgesiometer standardizes the amount of pressure applied to the vestibule to quantify levels of sensitivity and is used primarily in research.5 The tampon test on the other hand is self-administered. Pain is rated on the 11-point Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) from zero to 10, on the total tampon insertion and removal experience. The tampon test has previously been evaluated to be reliable and to have good construct validity and responsiveness for women with PVD 4. The test has been used as a primary outcome measure in various clinical trials for vulvodynia ranging from case studies,6 case series,7 to several randomized clinical trials (RCTs).8-12 Furthermore, the tampon test has been used as part of the trial inclusion process, where an average pain level of four, or greater, on the NRS has been required to fulfil the eligibility criteria.9,10,13,14 Nevertheless, it is unknown if pain experienced during this test is proportional to, or representative, for the pain experienced during intercourse, or if such inclusion criteria may deprive some women with PVD from study participation. PVD women’s experiences with the tampon test has, to our knowledge, not been previously studied. The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the tampon test as a primary outcome measure in preparation for an upcoming RCT.

METHODS

Study Design

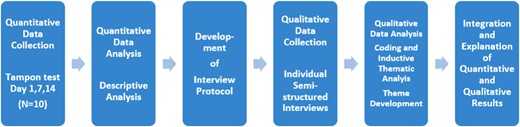

The data presented here are part of a preliminary study for an upcoming RCT. This coming trial will assess the effectiveness of a multimodal physiotherapy intervention versus treatment as usual in provoked localized vestibulodynia (ProLoVe project). In this mixed methods study we applied an explanatory sequential design (Figure 1). Tampon test data was collected first and these findings were subsequently used to guide the development of the interview protocol. In the final stages, tampon test data and interview findings were brought together to see how qualitative findings could help to explain the quantitative findings.15

A diagram of the quantitative and qualitative phase and the procedures used in this explanatory sequential mixed methods study design. (Figure 1 is available in color online at www.jsm.jsexmed.org.)

Participants

Ten women with confirmed PVD were recruited from the Vulva Clinic, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, at Oslo University Hospital, Norway. Participant’s eligibility assessment was based on a comprehensive gynecologic examination and medical history, using a standardized protocol for PVD diagnosis.16 Patients were invited to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) pain experienced during intercourse, pressure applied to the vulvar vestibule or usage of tampon; 2) aged between 18 and 35 and 3) fluent in the Norwegian language. Exclusion criteria included the presence of active infection or dermatologic lesion in the vulvar region. The same sample was used in the quantitative and qualitative phase of the study.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in South East Norway (2018/1036), and registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04208204 (NCT04208204). Data was collected in 2019.

At the Vulva Clinic, all eligible patients were verbally informed about the study and received an information leaflet. Those interested in study participation contacted the primary investigator, who invited them to a meeting at Oslo Metropolitan University for further information about the study. Eighteen patients were found eligible for participation between February and May 2019. Ten out of 18 patients contacted the primary investigator, agreed to take part in the study and signed informed consent after the meeting.

Data Collection

All the quantitative data were collected via electronic forms and then transferred directly in a secured manner to the Services for Sensitive Data (TSD), at the University of Oslo. The interviews were recorded and encrypted with a Dictaphone app developed by the university, called “nettskjema-diktafon”. This again insured immediate and direct transfer of the files to the TSD research server. After decryption, the interviewer transcribed the interviews verbatim.

The Tampon Test

The tampon test was chosen as the primary outcome measure based on recommendations for self-report outcome measures in vulvodynia clinical trials.17 This self-administered pain eliciting method measures degree of pain intensity during tampon insertion and removal. In this study, all participants were provided with the original Regular TampaxTM Tampons, supplied in standard cardboard applicator for insertion, which is the same type of tampon used in the validity study.4 This specific type of tampon is no longer available in Norway and was therefore ordered from the Internet. At the first meeting detailed instructions about how to undertake and record the tampon test were given, as described by Foster et al (2009).4 The test was undertaken in the evening on day 1, 7 and 14, a similar procedure to the Foster study, as a part of the baseline assessment. Day 1 was defined as the first day the participant performed the tampon test. The participants were instructed to insert and immediately remove the tampon, and then record the degree of pain on the NRS, based on the entire experience. The participants were instructed not to lubricate the tampon or use pain relief (i.e. topical lidocaine) prior to insertion. In addition, participants recorded whether they were menstruating during the time of the test. The tampon test together with other validated pain measures such as the Female Sexual Function Index 18 and pain intensity (NRS) during intercourse in the past four weeks were assessed at baseline, post-treatment and at the eight months follow-up.

Qualitative Interviews

As part of this preliminary study all participants received multimodal physiotherapy for PVD, after the completion of baseline assessment. The time frame for the intervention varied from two months up to four months. Towards the end of the treatment period (11.4 treatments on average), all participants were interviewed individually face to face. During the planning phase it was decided to interview every participant since the study would only include ten in total. After the quantitative data collection, baseline data was analyzed, discussed by the research team and used in the development of the semi-structured interview guide. The interviewer was provided with the participant’s tampon test scores prior to the conduction of each interview.

A phenomenological worldview informed the qualitative approach, where the aim was to explore and give voice to the subjects’ perspectives and lived experiences. 19 A descriptive and inductive qualitative design was chosen, seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the physiotherapy intervention and the tampon test.20 For the purpose of this paper only the qualitative findings related to the women’s experiences with the tampon test will be presented. The second author of this article, a female physiotherapist experienced with qualitative interviews, conducted the interviews and was not involved in the delivery of the treatment. The interviews took place in the physiotherapy outpatient clinic at Oslo Metropolitan University, each interview lasting between 60 to 90 minutes. A semi-structured interview guide was used to ensure each area of interest was addressed during the interviews, while at the same time encouraging the women to speak freely about their experiences.19 The interviewer introduced the topic of the tampon test with an open-ended question, asking the participants to share their experiences with the test as a measure of their vulvar pain. To elicit rich descriptions, the interviewer tried to follow up salient cues and themes in the participants’ answers, inviting them to elaborate, provide examples, or to clarify where appropriate. The interviewer was on the lookout for variations, different angles, and conflicting viewpoints, to promote a nuanced data material. 19 The final two interviews added little new information to the analysis, and we therefore consider that data saturation was reached at this point.

Mixed Methods Data Analysis

The quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed separately. First, an individual mean pain intensity score was calculated from the tampon test measurements. Intra-individual variability in pain intensity scores was calculated as a median spread difference between the highest and the lowest pain intensity score. The descriptive data has been presented as frequencies and median scores. Estimation of pain intensity with the tampon test is presented as median (min; max; Q1; Q3) scores and for all the other measures data are presented as median (Q1; Q3).

In the second qualitative phase an inductive thematic analysis was performed by the interviewer.20 Attentive reading and re-reading of the transcripts helped to discern central aspects in the women’s experiences and initial codes were identified. Taking care to include both common and diverging experiences, these initial codes were then reworked into a thematic map (included in supplementary materials Appendix A). This map consisted of themes and subthemes seeking to represent the main topics identified in the interviews. The first and second author independently reviewed the map for validity against the dataset and refined the themes and subthemes until agreement between the authors was reached. The findings are presented as analytical summaries and illustrative quotes for each of the main themes.

In the last stage, quantitative and qualitative data analysis were integrated in a joint display to illustrate both the tampon test data and qualitative interviews. This also showed how the qualitative data helped to explain the quantitative data (included in supplementary materials Appendix B).

RESULTS

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1 . Ten nulliparous women with PVD, median age 21 (18 to 33), took part in the study. Two women had sexual intercourse in the last four weeks, prior to the tampon test. Seven of the women reported different comorbidities including jaw pain, muscle pain and twitching, anal pain, endometriosis, headache, migraine, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome and alopecia areata. At baseline, four subjects were on oral contraceptives; one on cerazette, one on marvelon and two on oralcon. In terms of concurrent drug use all participants reported to have tried topical lidocaine. At baseline, six patients used topical lidocaine on a weekly to daily basis. In addition, one participant was on systemic treatment with amitriptyline, another on levothyroxine and one on diclofenac.

| Characteristics . | Participants n = 10 . |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 21 (20; 26) |

| Pain duration (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 7 (3; 8) |

| Primary PVD | 7 |

| Relationship category | |

| Married/common law | 2 |

| In a relationship | 2 |

| Single | 6 |

| Childbirth | 0 |

| Intercourse past 4 weeks | 2 |

| Education category | |

| High school student | 1 |

| Undergraduate student | 7 |

| Completed bachelor’s degree | 2 |

| Work category | |

| Student | 9 |

| Part time work | 5 |

| Full time work | 1 |

| Unemployed | 0 |

| Participants with comorbidities | 7 |

| BMI, median (Q1; Q3) | 23 (20; 23) |

| Characteristics . | Participants n = 10 . |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 21 (20; 26) |

| Pain duration (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 7 (3; 8) |

| Primary PVD | 7 |

| Relationship category | |

| Married/common law | 2 |

| In a relationship | 2 |

| Single | 6 |

| Childbirth | 0 |

| Intercourse past 4 weeks | 2 |

| Education category | |

| High school student | 1 |

| Undergraduate student | 7 |

| Completed bachelor’s degree | 2 |

| Work category | |

| Student | 9 |

| Part time work | 5 |

| Full time work | 1 |

| Unemployed | 0 |

| Participants with comorbidities | 7 |

| BMI, median (Q1; Q3) | 23 (20; 23) |

| Characteristics . | Participants n = 10 . |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 21 (20; 26) |

| Pain duration (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 7 (3; 8) |

| Primary PVD | 7 |

| Relationship category | |

| Married/common law | 2 |

| In a relationship | 2 |

| Single | 6 |

| Childbirth | 0 |

| Intercourse past 4 weeks | 2 |

| Education category | |

| High school student | 1 |

| Undergraduate student | 7 |

| Completed bachelor’s degree | 2 |

| Work category | |

| Student | 9 |

| Part time work | 5 |

| Full time work | 1 |

| Unemployed | 0 |

| Participants with comorbidities | 7 |

| BMI, median (Q1; Q3) | 23 (20; 23) |

| Characteristics . | Participants n = 10 . |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 21 (20; 26) |

| Pain duration (yrs.), median (Q1; Q3) | 7 (3; 8) |

| Primary PVD | 7 |

| Relationship category | |

| Married/common law | 2 |

| In a relationship | 2 |

| Single | 6 |

| Childbirth | 0 |

| Intercourse past 4 weeks | 2 |

| Education category | |

| High school student | 1 |

| Undergraduate student | 7 |

| Completed bachelor’s degree | 2 |

| Work category | |

| Student | 9 |

| Part time work | 5 |

| Full time work | 1 |

| Unemployed | 0 |

| Participants with comorbidities | 7 |

| BMI, median (Q1; Q3) | 23 (20; 23) |

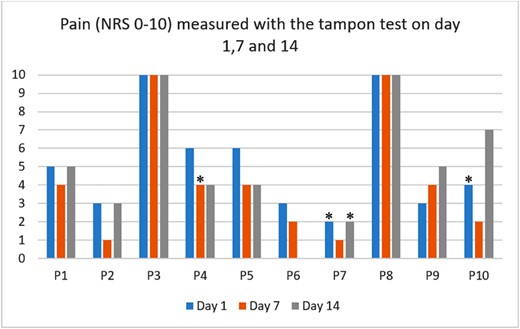

Individual pain intensity scores are presented in Figure 2 . At baseline, the median pain intensity measured with the tampon test was 4.5 (min=1.7; max=10; Q1=2.5; Q3=6). Post treatment median pain intensity was 2 (min=0; max=7, Q1=1.5; Q3=4.2) and at the eight months follow up it was 3.5 (min=0.7; max=8; Q1=1.8; Q3=4.5). At baseline and post-treatment, the median spread difference in pain intensity between the highest and the lowest scores were two points, and at the eight months follow-up it was one point. At baseline, the maximum spread difference on the NRS was five and the minimum was zero (Figure 2). Post treatment and at the eight months follow-up the maximum spread difference was four and the minimum was zero.

Individual pain intensity measured in 10 participants with the tampon test on day 1, 7 and 14 with the Numeric Rating Scale, where zero is no pain and 10 worst possible pain. One participant (P6) did not complete tampon test on day 14. P = participant. * = menstruation. (Figure 2 is available in color online at www.jsm.jsexmed.org.)

Two participants reported to have had intercourse in the last four weeks prior to baseline assessment, rating their pain intensity levels during intercourse on the NRS. P2 scored 10 on the NRS during intercourse whereas the mean NRS tampon test score was 2.3. P5 scored seven on the NRS during intercourse while the mean NRS tampon test score was 4.7.

Qualitative Findings

Four main themes were conceptualized through the qualitative analytical process, representing central aspects of the participants’ experiences with the tampon test: 1) pain sensation and pain intensity, 2) fluctuating pain intensity, 3) unfamiliar tampons and 4) the significance of context.

Theme 1: Pain Sensation and Pain Intensity

The analysis suggests that overall, the pain sensation and intensity experienced during the test was not comparable to intercourse pain. It was noted, however, that for P1 and P5, pain sensation and location was the same as experienced during intercourse. Although both reported that the test was less painful than intercourse, and the testing context entirely different, these women felt it to be both relevant and useful. P2, P4, P6, P7, P8 and P10 on the other hand reported that the pain sensation experienced during the test was different to pain during intercourse, as expressed by P10: “For me, it was not the same feeling. Or it wasn’t the same pain.” Intercourse pain was described as more complex, intense and extensive. P6 described how the pain during the test was comparable to intercourse pain in some ways, but different at the same time. To her the intercourse pain was much worse and more widespread: “I experience some of the same pain, only a lot worse and at several different sites.”

Some key differences between a tampon and a penis were emphasized as important distinctions influencing the character and intensity of the pain sensation. The tampon was described as smaller, softer and more bendable than a penis, as expressed by P10: “It [the tampon] is smaller. And it is paper, so it’s bendable in a way (laughs). So no, it’s not the same.” Several pointed out that because of the smaller size and the more pliable nature of the tampon, it was possible to avoid the painful area: P4: “I don’t know if it [the test] is really relevant for me… because it is such an old type of Tampax. And it is not the same putting such a small thing in, which doesn’t touch anything. So you see, it doesn’t touch much of the area. It does hurt, but it is not the same pain as if you were having sex…”.

Because of its smaller size, the tampon also felt less intimidating. P2 reflects on the differences in psychological impact this might have had, where the tampon was experienced as a lot less threatening than a penis. Several participants also pointed out that the tampon is inserted once only, whereas a penis will move in and out repeatedly, causing significantly more friction and pain: P2: “No the tampon test is not comparable to painful intercourse, it is something completely different. I think it is completely different having something in there all the time than something that goes in and out, because there is more friction.” Although there is a dynamic aspect of the pain perception with the test, pain is short-lived, as expressed by P3: “And it is really painful to put it in, but once it is inside it no longer hurts. So it’s kind of short-lived.”

P7 expressed frustration over the test as she felt it did not manage to capture her pain. To her, using tampons had never been an issue and she felt that the test did not allow her to demonstrate her pain: “I felt the test failed to show how much pain I am in. Because putting a tampon in has never really been a problem for me. (…) The pain is there, but this test does not show it.” This made her question if she had come to the right place for help, or indeed, if she even had a “real” problem at all. Including P7, four of the participants were already using tampons before entering the study (P1, P2, P6, and P7). To them using a tampon was associated with no or little pain and therefore not considered an issue. Sexual intercourse, however, was a major issue for all 10 participants.

Theme 2: Fluctuating Pain Intensity

P2, P4, P5, P8 and P10 reported large fluctuations and rapid changes in their day-to-day vulvar pain intensity levels. P2: “It varies a bit because all days are different”. These fluctuations could be dramatic and frustrating, causing the women to question their own progress, as expressed by P4: “It varies a lot from day to day. One day I can think ‘Oh my god, it doesn’t hurt at all’, while the next day I can feel like I am back to scratch”. P8 had similar experiences: “I don’t know how others experience it, but for me the pain can vary a lot from one day to the next. So, I’m not sure that it [the test] will give a good indication of whether I have improved or not.” Consequently, she questioned what use this test held in informing the study of her recovery process.

For P2, P8 and P10, pain intensity would depend on where they were in their menstrual cycle: P10: “Sometimes it (the tampon test) hurt a lot, and then sometimes when I had my period it didn’t hurt so much”. While receiving multimodal physiotherapy, P8 discovered that inserting a tampon during her period was particularly easy. Increased lubrication during menstruation was viewed as a contributing factor.

Theme 3: Unfamiliar Tampons

Most women were unaccustomed to the test tampon. The Original Regular Tampax tampon was unfamiliar (P3, P5 and P6) and was described as old-fashioned (P4). The test tampons were described by P3 and P5 as more difficult than the ones they were used to, especially the cardboard sleeve: P3: “I think those tampons are a lot harder to insert than OB [common tampon brand used in Norway], because they are so unfamiliar, I am unsure how to use them. This cardboard sleeve, how are you supposed to… It is much easier to use your own fingers on the tampon itself.” Inserting the tampon with the cardboard sleeve gave a sense of less control and less physical sensation. Another woman described how she had to practice using the tampons prior to the test: P5: “I thought those tampons were a bit difficult to figure out. I spent a really long time trying to understand how to do it (laughs). I had to practice first, but I think I found out how they work (laughs).” One woman however, who was initially very skeptical to the test, found it surprisingly easy and thought it was due to a different brand: P9: “And it went surprisingly well. I was shocked. Because the tampon just slid right in and I thought ‘what is happening?’ (…) And I wonder if it might have had something to do with the brand, because I have normally used OB during my periods. It is not the same, so that might be the reason.”

Theme 4: The Significance of Context

Another aspect complicating the comparison of pain is the fact that inserting a tampon and having sexual intercourse represents two very different situations. Contextual and interpersonal factors, such as perceived levels of control, wanting to perform for a partner or to safeguard a partner’s feelings, were reported as important aspects. P2, P6, P8 emphasized that it was possible to experience more control whilst inserting a tampon compared to intercourse. Inserting a tampon can be done in the comfort of your own home and alone. If it sits in a painful position it is possible to remove it and place it in a more comfortable one. P2 emphasized that perceived control made a big impact on the way she experienced pain differently in these two situations. She described how a tampon could be maneuvered in a more predictable manner, whereas a penis to a larger extent is beyond her control. P2: “A tampon stays in a fixed position, while during intercourse the penis moves and can touch several places in the vagina. Because sometimes when I insert a tampon I realize, wow, this was painful, I then take it out and try again. But you can’t predict that if you have intercourse because you do not control it in a way”. P6 described how being in control during tampon insertion allowed her to adjust the angles and positions to minimize the tampon’s contact with the painful areas. This, and the fact that using a tampon seemed a less menacing everyday event, made it easier for her to relax in the situation: P6: “I am able to get a tampon in if I’m standing or something. But the body is totally different when you are having sex – how you are lying or sitting… The angles are different (laughs). (…) And you are less tense too, in a way. You are just inserting a tampon, which is something you do all the time.”

P8 also considered the aspect of control to be an important difference between inserting a tampon and having sex. At home, by herself, in a safe, calm and comfortable setting, she finds it easier to relax her body and consciously let go of tensions in her pelvic floor as she tries to insert the tampon. Sexual intercourse is very different situation as it involves an interpersonal dimension. Whereas a tampon is an inanimate object without preferences and expectations, sexual intercourse is very much a dyadic activity. You are with another person and taking into account his feelings. P8 described how she would accept and force her way through significantly higher levels of pain during intercourse than she would inserting a tampon. She jokingly, but importantly, pointed out that she does not feel the same pressure to “perform” for the tampon: P8: “In a way it is a different type of pain. Or… I often find that the tampon is not necessarily as painful as intercourse. During intercourse, I have to perform more because there is another person involved. Whilst the tampon is a thing, I do not care much about its feelings (laughs).”

Mixed Methods Results

The findings were achieved by employing a mixed methods approach. The joint display table is included in the supplementary material, Appendix B, to illustrate how the qualitative results can help to provide an explanation and deeper understanding of the quantitative findings.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate the tampon test as a possible primary outcome measure in PVD to be used in an upcoming RCT. The tampon test data demonstrated large intra- and inter-individual variability. In addition, four of the women had a NRS score that was equal to, or below four, which in some previous studies have been used as an exclusion criterion. These findings informed the set-up of the following qualitative phase exploring the women’s experiences with the tampon test. In the following section, we discuss these mixed methods findings within three main topics: 1) pain intensity with the tampon test 2) variability in the tampon test data and 3) pain sensation and experience during the tampon test.

Pain Intensity With the Tampon Test

Pain experienced during sexual intercourse is the main reason for women with PVD to seek treatment. In order to evaluate the effect of treatment it is important to utilize an outcome measure that is sensitive enough to pick up change following treatment. In this study, the median pain intensity score was 4.5 (Q1=2.5; Q3=6).which was similar to the findings in the validity study by Foster et al (2009), reporting a mean NRS of 4.6 ± 2.7.4 Other studies have reported higher mean tampon test scores, between 6.4 and 6.8.8,13 In all the above mentioned studies however, participants with a baseline score equal to four or lower were not included in the trials. In the current study four women had a mean pain intensity score of four or below on the tampon test. During the interviews, P1, P2, P6 and P7 reported that they normally use sanitary tampons. Interestingly three of these women (P1, P6 and P7) had an average pain score equal to four, or below. All 10 participants reported however, that sexual intercourse was a major challenge. These findings indicate that the tampon test might be a poor proxy for intercourse pain, especially for those with a low tampon test score. The test may underestimate the amount of pain some women experience during intercourse to a degree that it may lead to an exclusion of them from clinical studies. In comparing tampon test pain with intercourse pain, the latter was described as much worse, more intense and widespread. Foster et al. (2009) described similar findings, where some women reported a much higher level of intercourse pain compared to tampon test pain.4 It is possible however, that the tampon test can function better as a proxy for intercourse pain in women with high pain scores on the test.

P3 and P8 scored maximum pain intensity at each measurement point. P3 described how the Tampax tampon was difficult to understand how to use and both women found it impossible to insert, due to severe pain. P8 also described how she was not prepared to push herself and endure pain, in the same way she would during intercourse. She further described intercourse pain to be worse than tampon insertion, albeit she scored maximum on the tampon test. This can point to a possible ceiling effect and the test’s inability to capture all relevant dimensions of the pain experience. Overall, these experiences highlight the complexity of pain, in her case the possible existence of a strong interpersonal pressure to perform during intercourse, despite severe pain. Several previous studies have found that women continue to have penetrative intercourse, despite pain, and avoid telling their partner.21-23 Reasons for this phenomenon are described in the literature, but it is beyond the scope of this paper.

Variability in the Tampon Test Data

In the quantitative phase we found large variability in the tampon test scores, both intra- and inter-individually. A possible explanation for this variability could be the fluctuating and rapid change in the pain intensity levels experienced in daily life by several women. In addition, the interviewees described various factors that could have had an influence on pain intensity in the testing situation, such as fear of pain, the inability to relax, the extent of control, the type of tampon and cyclic hormonal changes. It is not possible however, to establish to what degree these factors contributed to day-to-day variability in experienced pain levels. It may be possible to reduce the variability in the tampon test data in future trials by selecting a test tampon familiar to the women, whilst giving clear instructions on how and when the test should be undertaken. Keeping a record of factors, such as menstruation, is important to investigate the potential influence of the menstrual cycle on pain during the tampon test. The most important aspect however, is to ensure that several repeated measurements are undertaken within a definite period, in order to provide an average pain intensity score.

Pain Sensation and Experience During the Tampon Test

Overall, the pain sensation and experience during the tampon test was not comparable to intercourse pain. Several women reported that the sensory aspect of pain experienced during the test was different to pain during intercourse. The tampon was smaller, softer and more pliable compared to a penis. Furthermore, the test was short-lived as once the tampon was inserted, the pain was gone. Intercourse however, involved repeated friction and movement over time, which possibly could have contributed to a more painful experience. The psychosocial context and setting was also described as entirely different. The psychological impact of experiencing the tampon as less threatening than a penis was reflected upon. Fear-avoidance variables, such as pain catastrophizing and pain related fear, have been shown to be associated with pain intensity in women with PVD.24-26 Hence, for some women the tampon test may pose as less threatening, because during tampon insertion the women inflict pain on themselves, rather than pain being inflicted upon them by their partner. Three women also reported to perceive more control in the test situation, compared to intercourse, which again could have had an effect on the pain experience.

In summary, most participants did not experience the tampon test as an adequate representation of intercourse pain. The test was less intense, different in nature and conducted in entirely different context. This is in line with Rosen et al.’s (2020) argument that the tampon and the context in which it is applied does not equate to the real life experience of pain during penetrative intercourse.27 In using the tampon test as a proxy for painful sexual activity, it may provide us with incomplete and insufficient estimates due to the lack of sexual context and sexual arousal in the testing situation. Nevertheless, not all women shared this opinion; P1 and P5 described how pain sensation and location was the same. Although the context was entirely different and pain intensity less with the test, they still found it to be both relevant and useful.

Clinical Implications

The tampon test has several clear advantages; it is easy to undertake by the individual participant without the involvement of health care professionals and it is inexpensive and easy to repeat within a specified period. In addition, the usage of tampons mimic a periodic activity, which for some patients might be a partial goal of the therapy.

Despite its advantages, it is questionable whether the tampon test is an adequate primary outcome measure in PVD trials. A particular problem seems to be its inability to reproduce high enough pain intensity among some of the PVD patients, who concurrently report high levels of pain during sexual intercourse. This can lead to the exclusion of these particular patients from further clinical studies. Furthermore, this can diminish the sensitivity of the test in terms of registering clinically meaningful changes in the patient’s condition. An additional challenge is the large intra-individual variability found in test scores on different test days. Consequently, it necessitates several measurements per assessment time point in order to increase precision in the estimation of an overall pain intensity. The fact that for the majority of patients the test was not an instrument that represented their main problem adequately, i.e. pain during intercourse, is an issue we believe that should be taken into account. If the main assessment instrument seems irrelevant to the study participants, it may negatively influence their engagement and compliance.

Nevertheless, we would argue that the tampon test could serve well as a secondary outcome for measuring pain intensity in women with PVD. In contrast to memory-based self-report questionnaires, the tampon test provides a real time estimate of pain intensity in the vulvar vestibule. The usage of several different types of pain outcome measurements in clinical studies is in line with current IMPPACT guidelines28 and vulvodynia research recommendations27, as it provides a more comprehensive picture of the pain experience.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

To our best knowledge, this is the first study investigating women’s experiences with the tampon test in a sample of women with PVD. A strength of this study was how these experiences could be directly linked to the quantitative data, as all participants were interviewed. Nevertheless, although appropriate for a feasibility study, a limitation in this study was the small sample size in the quantitative phase, hence the quantitative findings should therefore be interpreted with caution. The findings are therefore not generalizable to a larger population.

CONCLUSION

To our best knowledge this is the first study investigating women’s experiences with the tampon test in PVD. The experiences with the test could be directly linked to the tampon test data, as all participants in this study were interviewed. This study suggests that despite its merits, the tampon test by itself may be suboptimal as a primary outcome measure in PVD research. As a proxy for pain intensity during sexual intercourse, the tampon test may underestimate levels of pain intensity among some participants with PVD. This could lead to exclusion of these participants from clinical studies, or decrease the test’s ability to register meaningful clinical changes. The majority of participants perceive the test as an irrelevant measure of their problem. For future clinical trials, we therefore recommend a primary outcome measure that is capable of capturing the multidimensionality of PVD, such as the Female Sexual Function Index18. Nevertheless, the tampon test may be important as a secondary outcome providing a real time estimation of vestibular pain intensity. The test should be undertaken repeatedly, in order to increase precision of the pain estimation.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

Category 1 (a) Conception and Design Gro Killi Haugstad; Anne Lise Ording Helgesen; Slawomir Wojniusz. (b) Acquisition of Data Mette Bøymo Kaarbø; Kristine Grimen Danielsen; Anne Lise Ording Helgesen; Slawomir Wojniusz (c) Analysis and Interpretation of Data Mette Bøymo Kaarbø; Kristine Grimen Danielsen Category 2 (a) Drafting the Article Mette Bøymo Kaarbø (b) Revising the Article for Intellectual Content Mette Bøymo Kaarbø; Kristine Grimen Danielsen; Gro Killi Haugstad; Anne Lise Ording Helgesen; Slawomir Wojniusz Category 3 (a) Final Approval of the Completed Article Mette Bøymo Kaarbø; Kristine Grimen Danielsen; Gro Killi Haugstad; Anne Lise Ording Helgesen; Slawomir Wojniusz.

Funding

Funding from Oslo Metropolitan University and the Norwegian Fund for Post-Graduate Training in Physiotherapy.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.03.010.

Trial registration: This study is registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04208204 (NCT04208204).

REFERENCES

Author notes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.