-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Diane Chen, Elaine Shen, Victoria D Kolbuck, Afiya Sajwani, Courtney Finlayson, Elisa J Gordon, Co-design and usability of an interactive web-based fertility decision aid for transgender youth and young adults, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 50, Issue 1, January 2025, Pages 40–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsae032

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To develop a patient- and family-centered Aid For Fertility-Related Medical Decisions (AFFRMED) interactive website targeted for transgender and nonbinary (TNB) youth/young adults and their parents to facilitate shared decision-making about fertility preservation interventions through user-centered participatory design.

TNB youth/young adults interested in or currently receiving pubertal suppression or gender-affirming hormone treatment and parents of eligible TNB youth/young adults were recruited to participate in a series of iterative human-centered co-design sessions to develop an initial AFFRMED prototype. Subsequently, TNB youth/young adults and parents of TNB youth/young adults were recruited for usability testing interviews, involving measures of usability (i.e., After Scenario Questionnaire, Net Promotor Score, System Usability Scale).

Twenty-seven participants completed 18 iterative co-design sessions and provided feedback on 10 versions of AFFRMED (16 TNB youth/young adults and 11 parents). Nine TNB youth/young adults and six parents completed individual usability testing interviews. Overall, participants rated AFFRMED highly on measures of acceptability, appropriateness, usability, and satisfaction. However, scores varied by treatment cohort, with TNB youth interested in or currently receiving pubertal suppression treatment reporting the lowest usability scores.

We co-created a youth- and family-centered fertility decision aid prototype that provides education and decision support in an online, interactive format. Future directions include testing the efficacy of the decision aid in improving fertility and fertility preservation knowledge, decisional self-efficacy, and decision satisfaction.

Gender-affirming medical interventions (i.e., pubertal suppression; gender-affirming hormones) are considered a standard-of-care treatment for gender dysphoria among transgender and nonbinary (TNB) youth and young adults (Coleman et al., 2022; Hembree et al., 2017). These treatments are effective in reducing gender dysphoria and improving psychosocial outcomes (Achille et al., 2020; Allen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2023; Costa et al., 2015; de Vries et al., 2014; Kuper et al., 2020; van der Miesen et al., 2020). However, pubertal suppression treatment and gender-affirming hormones (GAH; testosterone or estrogen) have implications for fertility (Finlayson et al., 2016; Moravek et al., 2020; Nahata et al., 2019).

Pubertal suppression is achieved using gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRHa), which prevent oocyte maturation and sperm production by suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (Finlayson et al., 2016). This process is reversible; if GnRHa is discontinued, endogenous puberty will progress allowing for oocyte maturation and spermatogenesis. However, the majority of TNB youth who receive pubertal suppression treatment later initiate GAH (Brik et al., 2020). Exogenous testosterone and estrogen have been linked to changes in ovarian histology and impaired spermatogenesis, respectively. However, the implications of these changes on birth rates, and the reversibility of these changes if GAH are discontinued, are not clear (Moravek et al., 2020; Nahata et al., 2019). Given the potential for these treatments to negatively affect fertility, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (Coleman et al., 2022), the Endocrine Society (Hembree et al., 2017), and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2015) recommend that TNB youth/young adults are counseled about the potential impairing effects of gender-affirming medical treatment on fertility and the availability of fertility preservation options such as oocyte and sperm cryopreservation.

Despite these recommendations, and reported practice patterns suggesting TNB youth are being routinely counseled about fertility (Chen et al., 2019a), few TNB youth pursue fertility preservation interventions. Across three studies, fewer than 5% of TNB youth completed oocyte or sperm cryopreservation prior to initiating GAH (Chen et al., 2017; Nahata et al., 2017; Wakefield et al., 2019). These fertility preservation rates among TNB youth are significantly lower than the 24%–36% of TNB youth reporting a desire for future biogenetic children (Chen et al., 2018; Persky et al., 2020; Strang et al., 2018). Many factors affect TNB youths’ decision-making about fertility preservation interventions, including future parenthood desires, individual experiences of gender dysphoria, family values around biogenetic parenthood, and financial considerations (Chen et al., 2019b). Research suggests that fertility preservation counseling that is deemed inadequate by TNB youth negatively impacts fertility decision-making and decision-making satisfaction (Chen et al., 2019b).

Fertility counseling for TNB youth is complex for a variety of reasons. First, research on the effects of gender-affirming medical interventions on fertility is limited and conflicting (Nahata et al., 2019). There are no data on the duration or dose of GAH exposure that leads to negative fertility outcomes, and no conclusive evidence exists that GAH permanently impairs fertility among those who initiate GAH after pubertal maturity in the absence of past GnRHa treatment. Second, pediatric fertility preservation options and assisted reproductive technologies are rapidly evolving and particularly complicated for peripubertal youth pursuing GnRHa who typically have not progressed sufficiently through endogenous puberty to pursue non-experimental fertility preservation interventions (Finlayson et al., 2016). Third, youth must consider their parenting desires and intentions during a developmental stage in which family planning is not developmentally normative (Chen & Nahata, 2021). Fourth, TNB minors require parental consent for both GAH and fertility preservation interventions, which introduces complications when youth and parents disagree about whether to pursue fertility preservation interventions (e.g., parents withholding consent for GAH unless youth complete fertility preservation) (Chen et al., 2019b). This highlights the need for fertility counseling to effectively target both TNB youth and their parents. Last, impaired fertility typically affects future quality of life rather than current functioning (Canada & Schover, 2012; Nilsson et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2015). These complexities are further compounded by pediatric transgender health providers’ perceptions that they need more education and training to effectively counsel their patients about fertility and fertility preservation (Tishelman et al., 2019).

Digital health technologies, such as web-based patient education and decision support tools, have strong potential for augmenting standard-of-care counseling and addressing service gaps attributable to time, staffing constraints, and provider knowledge and comfort in providing fertility counseling for TNB youth and their families (Ren et al., 2015). Digital decision aids are evidence-based educational tools designed to address individual values and preferences in the context of shared healthcare decision-making (Lopez-Olivo & Suarez-Almazor, 2019). Decision aids allow for both standardized and tailored patient education, and the flexibility and confidentiality of addressing a sensitive topic like fertility and reproductive health in a more comfortable setting, outside of a traditional face-to-face healthcare encounter. The context of discussing fertility is particularly important for TNB youth and young adults, who routinely face barriers to accessing culturally competent care due to insufficient clinician knowledge, experience, and sensitivity (Oransky et al., 2019; Romanelli & Lindsey, 2020), and perceived stigma or overt discrimination from nonaffirming clinicians (Gridley et al., 2016; Romanelli & Lindsey, 2020). In addition, research suggests decision aids increase patient knowledge and reduce decisional conflict without increasing anxiety (O'Connor et al., 2009). Furthermore, a digital decision aid is highly scalable for broad dissemination beyond embedding the tool within the current workflows of gender health programs. Disseminating a digital fertility decision aid direct-to-consumer in the public domain can help address disparities in health care knowledge and utilization among TNB youth, as well as the public health imperative to “meet people where they are at,” as we know that TNB youth seek information, support, and resources online at higher rates than do they offline (McInroy et al., 2019).

Informed by the Ottawa Decision Aid Framework (Legare et al., 2006) and the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (Volk et al., 2013), and consistent with the Accelerated Creation-to-Sustainment framework for digital health intervention development (Mohr et al., 2017), we employed user-centered participatory design to develop a patient- and family-centered Aid For Fertility-Related Medical Decisions (AFFRMED) interactive website targeted for TNB youth and their parents. In this article, we describe our digital decision aid development process and final functional web-based AFFRMED decision aid ready for efficacy evaluation.

Methods

Decision aid development overview

Methods for creating prototypes and conducting co-design sessions were adapted from principles using human-centered design (Brown, 2008). Human-centered design is a problem-solving framework, often used in the fields of technology, business, and increasingly healthcare, that uses a creative approach involving co-creation with intended users throughout the entire design process. Human-centered design is an iterative process that entails multiple cycles of prototype development, testing with users, and incorporating user feedback before a refined product is piloted in its native environment (Brown, 2008). Our human-centered design methods involved four sequential phases. Phase 1 comprised concept and wireframe development informed by our preliminary research with TNB youth, their parents, and multidisciplinary gender health and reproductive medicine providers (Chen et al., 2019a, 2019b; Kolbuck et al., 2020; Quain et al., 2021; Sajwani et al., 2022; Tishelman et al., 2019), as well as an interactive workshop with gender-inclusive sexual health education experts. Phase 2 involved conducting multiple co-design sessions with users to develop a low-fidelity prototype. Phase 3 entailed conducting multiple usability testing interviews to create a high-fidelity semi-functional web prototype. Both Phase 2 co-design sessions and Phase 3 usability testing interviews involved multiple iterations of prototyping, testing, and incorporating feedback from users. Phase 4 consisted of pilot testing the preliminary efficacy of AFFRMED. This paper focuses on Phases 1–3.

Intended audience and decision support needs

AFFRMED was designed to support fertility decision-making among TNB youth and young adults considering gender-affirming medical interventions that may impair fertility, as well as their parents, given the need for parental consent for minors to access both gender-affirming and fertility preservation interventions. Content domains and learning objectives for AFFRMED were informed by a decisional needs assessment of TNB youth and young adults and their parents (Chen et al., 2019b; Quain et al., 2021; Sajwani et al., 2022), and finalized through a Delphi consensus study with 80 multidisciplinary experts in pediatric transgender health, reproductive medicine, and/or fertility preservation (Kolbuck et al., 2020). The research team drafted content that aligned with the five key educational domains (human reproduction, gender-affirming treatments and their known/unknown effects on fertility, fertility preservation interventions, benefits and risks of fertility preservation interventions, and additional choices related to family building) and 25 learning objectives that reached expert consensus for inclusion and were identified as priorities for the decision aid. Content readability was evaluated with the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Test Tool (Flesch, 1948), and effort was made to reduce reading levels when possible. Some relevant medical terminology such as “testosterone” was not changeable; thus, the overall reading level remained higher than desired, informing the decision to have options for audio narration of text throughout the decision aid.

Design

Decision aid illustrations used minimalist design principles and gender-neutral color palettes (e.g., green and yellow to represent ovarian and testicular function, respectively). Early development of wireframes for AFFRMED incorporated common web app components, including a home screen, a toolbar for navigation between chapters, and arrows to navigate between pages within each chapter. Early concepts of AFFRMED with basic wireframes, illustrations, and content domains were presented in an informal design workshop to research and program staff within the Potocsnak Family Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (Lurie Children’s). This group specializes in delivering gender-inclusive sexual health education for youth in kindergarten through high school and works with TNB youth and young adults in the context of research. Several members of this group also self-identified as TNB individuals. Staff provided guidance regarding gender inclusivity for the early design of visual assets and provided feedback on the developmental appropriateness of language. Based on this feedback, a low-fidelity prototype designed in Keynote—a presentation program that allows fast, iterative prototyping and simple animations—was developed for design sessions with intended users.

AFFRMED testing and refinement occurred across two phases: a co-design session phase and a usability testing interview phase. During the co-design session phase, participants were invited to provide feedback on a low-fidelity prototype of AFFRMED focusing on content and visual asset design. In between each prototype version, a gestalt majority consensus (among AFFRMED study team members and users) regarding content and design features was reached and incorporated into the next version for testing. After 10 iterative versions tested during co-design sessions, users and researchers reached majority consensus for the next phase of testing and the low-fidelity prototype was used to develop a high-fidelity semi-functional web prototype. This high-fidelity prototype was tested during usability testing interviews to assess navigation, accessibility, and functionality. Usability testing interviews also involved iterative testing of three versions of the prototype.

Participant recruitment

Eligible participants included TNB youth ages 8–14 years who were considering or actively treated with GnRHa, youth and young adults ages 13–24 years who were considering or actively treated with GAH, and parents of youth in each cohort. We recruited potential participants from a subspecialty gender health clinic in Chicago, Illinois, and via community-wide advertisement (e.g., study flyers at LGBTQ-serving community-based organizations) in the Chicagoland area. Eligibility criteria and consent procedures for both co-design sessions and usability testing interviews were identical.

Interested potential participants were screened for eligibility, and eligible participants provided informed consent and parents provided permission for minors to participate. Participants were invited to a virtual co-design session or usability testing interview via a secure video platform with screen-sharing and remote-control capabilities. No identifying information was shared through this video platform. All study procedures were approved by Lurie Children’s Institutional Review Board (IRB#: 2018-2263). Data are available upon request.

Procedures

Co-design sessions

Co-design sessions were conducted with individual participants, youth and parent dyads, small groups with multiple youth together, and small groups with multiple parents together between June and August 2020. Participants were provided options for co-design session configuration to offer flexibility. Co-design sessions were conducted by moderators (E.S., V.D.K., A.S.) who followed a semi-structured interview guide (see online supplementary material). Each session began with an overview of the decision aid. Next, moderators presented decision aid pages in sequential format and asked participants to use a think-aloud framework to provide feedback. Participants indicated where they wanted the researcher to navigate on the screen and were asked what they thought would happen if a certain button or visual asset (e.g., graphic such as the notepad visual graphic) was clicked on. Participants read and interacted with a passage and were asked to state their understanding of the text, what they liked about the presentation format, and what they wished could be changed or modified. Participants also utilized the “annotate” feature of the video platform to draw out ideas or circle features about which they were giving feedback. Upon concluding each design session, participants were asked to list 1–2 key takeaways of new information learned, comment on the tone and inclusivity of AFFRMED, and relay whether they would use AFFRMED.

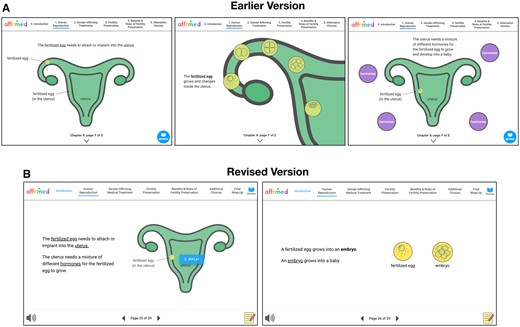

The lead moderator (E.S.) annotated notes on paper prototypes, while additional study team members took in-depth notes including verbatim quotations from participants. Immediately following co-design sessions, field notes were compiled into a Word document and moderators rapidly organized participant feedback into broad categories aligning with interview guide prompts. These content areas included: presentation of content, visual aesthetics, ease of use, overall impressions of the decision aid, tone of decision aid, and areas for improvement. Between each co-design session, the moderators and the PI (D.C.) met to discuss participant feedback and determine whether changes were necessary prior to the next co-design session as indicated by gestalt majority consensus. Prototypes were modified incorporating feedback regarding content, language, and visual assets, and tested again with new participants in an iterative fashion. Thus, later participants interacted with more refined versions of the decision aid than earlier participants did. If participants voiced confusion about specific design choices (e.g., the image of the fertilized egg evolved to depict cell division), we tested different versions of design elements in subsequent sessions (see Figure 1). Given that we had only one contact per study participant, participants did not have an opportunity to review and possibly correct raw data. Co-design sessions lasted approximately 90 min and were audio recorded as backup to field notes.

Creating iterations based on participant feedback. (A) In the earlier version, participants noted the fertilized egg did not stand out due to the green on green color. Participants also voiced confusion regarding the explanations and visuals depicting development of the fertilized egg. (B) In the revised version, the color of the fertilized egg was made brighter to be more noticeable. Concepts regarding the anatomy and physiology of fertilization were simplified which reduced confusion in the revised version.

Usability testing interviews

Individuals who did not participate in co-design sessions were recruited for usability testing interviews conducted between February and March 2021. Participants navigated through AFFRMED via the screen-sharing and remote screen control features of the video platform used for the study visits, and the research staff elicited their thoughts about the website design and functionality. Specifically, participants were asked to navigate between website chapters and pages and complete certain tasks, such as finding the glossary or how to use the notepad feature. Participants were asked what their overall opinions were about using AFFRMED, including what they felt would improve the experience of using the website. The first seven participants completed usability testing interviews using the first version of the semi-functional prototype, the next six participants used the second version, and the last two participants used the third version. Consistent with design sessions, we proceeded with testing subsequent versions after a gestalt majority consensus regarding content and design features was reached among study participants. Participants completed measures of usability and satisfaction after using AFFRMED. Usability testing interviews lasted approximately 45–60 min.

Measures

Demographics

Demographics were collected from both co-design session and usability testing interview participants. Youth, young adult, and parent participants self-reported their designated sex at birth, gender identity, race/ethnicity, age, and highest completed education level. Parent participants also reported their child’s designated sex at birth, gender identity, race/ethnicity, age, and highest completed education level.

After Scenario Questionnaire

The After Scenario Questionnaire (ASQ) is a 3-item measure of satisfaction with ease of completion, time commitment, and adequacy of available support information. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale and averaged (Lewis, 1995). Possible scores ranged from 1 to 7; lower scores reflect greater satisfaction.

Net Promoter Score

The Net Promoter Score (NPS) is a single item assessing the likelihood that users would recommend AFFRMED to a friend on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all likely” to “Extremely likely” (Adams et al., 2022). Responses were categorized into three groups: “Detractors” (ratings 0–6), “Passives” (ratings 7–8), and “Promoters” (ratings 9–10). The total NPS was obtained by subtracting the percentage of Detractors from the percentage of Promoters, with scores ranging from −100 (all Detractors) to +100 (all Promoters). Average scores above 50 are considered acceptable by industry standards (Reichheld, 2003). Health-related studies assessing patient-reported outcomes report average scores between 44 and 83 (Busby et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2014; Stirling et al., 2019).

System Usability Scale

The System Usability Scale (SUS) is a 10-item measure (e.g., “I felt very confident using the decision aid”; “I thought there was too much inconsistency in this decision aid”) rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.” (Brooke, 1996). Possible SUS scores ranged from 0-100, with a score of 68 or higher considered to be “above average” usability.

Analyses

Quantitative analyses were conducted in SPSS version 28. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics and measures of usability and satisfaction. Field notes documenting participant feedback from co-design sessions were grouped by a priori content areas using a general deductive approach immediately following each session by moderators (E.S., V.D.K., A.S.) and discussed with the PI (D.C.) during weekly meetings to determine whether changes were necessary prior to the next co-design session.

Results

Co-design sessions

Participants

Eighteen co-design sessions were conducted with 27 participants who provided feedback on a total of 10 iterative versions of AFFRMED. Youth participants ranged in age from 10 to 24 years, M(SD) = 17.06 (4.58), and parent participants ranged in age from 36 to 53 years, M(SD) = 46.5 (6.35). Table 1 presents additional demographic characteristics. Twelve youth/young adults interested in or actively taking GAH, four youth interested in or actively taking GnRHa, four parents of youth interested in or actively taking GAH, and seven parents of youth interested in or actively taking GnRHa participated.

| Youth/young adults . | Parents . | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Co-design sessions | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (25.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| GAH cohort | 12 (75.0) | 4 (36.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 11 (68.8) | 9 (81.8) |

| Male | 5 (31.3) | 2 (18.2) |

| Gendera | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 10 (62.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 1 (6.3) | 9 (81.8) |

| Nonbinary/genderqueer | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| Not sure | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 10 (62.5) | 8 (72.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 2 (12.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Asian | 4 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 4th grade | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| 5th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 7th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (54.5) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.5) |

| Usability testing | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| GAH cohort | 5 (55.6) | 2 (33.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 5 (55.6) | 6 (100) |

| Male | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Gender | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 3 (33.3) | 6 (100) |

| Gender fluid | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other (i.e., “enby and queer”) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 3 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Asian | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Black or African American | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Multiracial | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 1st grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 3rd grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 6th grade | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 1 (11.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 0 (0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Youth/young adults . | Parents . | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Co-design sessions | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (25.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| GAH cohort | 12 (75.0) | 4 (36.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 11 (68.8) | 9 (81.8) |

| Male | 5 (31.3) | 2 (18.2) |

| Gendera | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 10 (62.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 1 (6.3) | 9 (81.8) |

| Nonbinary/genderqueer | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| Not sure | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 10 (62.5) | 8 (72.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 2 (12.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Asian | 4 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 4th grade | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| 5th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 7th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (54.5) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.5) |

| Usability testing | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| GAH cohort | 5 (55.6) | 2 (33.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 5 (55.6) | 6 (100) |

| Male | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Gender | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 3 (33.3) | 6 (100) |

| Gender fluid | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other (i.e., “enby and queer”) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 3 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Asian | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Black or African American | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Multiracial | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 1st grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 3rd grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 6th grade | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 1 (11.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 0 (0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) |

Note. GAH = gender-affirming hormones.

Participants were given the following options for gender identity: (1) boy/man; (2) girl/woman; (3) trans boy/trans man; (4) trans girl/trans woman; (5) nonbinary; (6) gender fluid; (7) genderqueer; (8) not sure; (9) other. We collapsed the responses into the categories listed in the table based on the options selected. All parents reported cisgender identities.

| Youth/young adults . | Parents . | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Co-design sessions | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (25.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| GAH cohort | 12 (75.0) | 4 (36.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 11 (68.8) | 9 (81.8) |

| Male | 5 (31.3) | 2 (18.2) |

| Gendera | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 10 (62.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 1 (6.3) | 9 (81.8) |

| Nonbinary/genderqueer | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| Not sure | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 10 (62.5) | 8 (72.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 2 (12.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Asian | 4 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 4th grade | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| 5th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 7th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (54.5) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.5) |

| Usability testing | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| GAH cohort | 5 (55.6) | 2 (33.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 5 (55.6) | 6 (100) |

| Male | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Gender | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 3 (33.3) | 6 (100) |

| Gender fluid | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other (i.e., “enby and queer”) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 3 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Asian | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Black or African American | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Multiracial | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 1st grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 3rd grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 6th grade | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 1 (11.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 0 (0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Youth/young adults . | Parents . | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Co-design sessions | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (25.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| GAH cohort | 12 (75.0) | 4 (36.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 11 (68.8) | 9 (81.8) |

| Male | 5 (31.3) | 2 (18.2) |

| Gendera | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 10 (62.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 1 (6.3) | 9 (81.8) |

| Nonbinary/genderqueer | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| Not sure | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 10 (62.5) | 8 (72.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 2 (12.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Asian | 4 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 4th grade | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| 5th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 7th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (54.5) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.5) |

| Usability testing | ||

| Cohort | ||

| Blocker cohort | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| GAH cohort | 5 (55.6) | 2 (33.3) |

| Designated sex at birth | ||

| Female | 5 (55.6) | 6 (100) |

| Male | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Gender | ||

| Boy/man/trans boy/trans man | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) |

| Girl/woman/trans girl/trans woman | 3 (33.3) | 6 (100) |

| Gender fluid | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other (i.e., “enby and queer”) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Latinx/e White | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) |

| Latinx/e White | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Latinx/e non-White | 3 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Asian | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Black or African American | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Multiracial | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Highest completed education | ||

| 1st grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 3rd grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 6th grade | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| 8th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| 10th grade | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate, GED | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| Some college or technical degree | 1 (11.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 0 (0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) |

Note. GAH = gender-affirming hormones.

Participants were given the following options for gender identity: (1) boy/man; (2) girl/woman; (3) trans boy/trans man; (4) trans girl/trans woman; (5) nonbinary; (6) gender fluid; (7) genderqueer; (8) not sure; (9) other. We collapsed the responses into the categories listed in the table based on the options selected. All parents reported cisgender identities.

Co-design session feedback

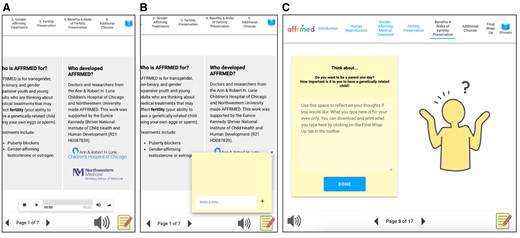

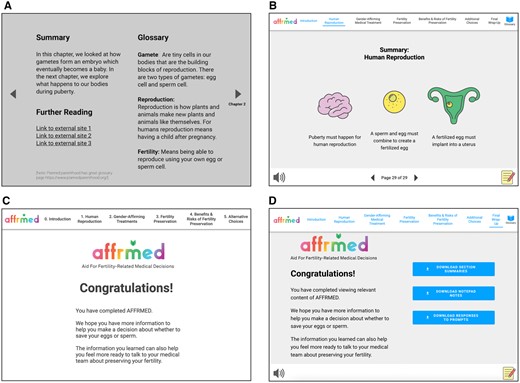

Several design elements resulted from co-creation with and feedback from participants during co-design sessions (Figure 2). These included a notepad feature, an audio button launching text narration (voiceover work completed by a TNB young adult), and a decision-making prompt. Figure 3 illustrates the progression from initial to final prototype, highlighting key features described above. Participants lauded AFFRMED’s use of terminology to describe human anatomy without using gendered terms. The content was perceived as accessible to youth and young adults of various ages, and design elements and imagery aided in multimodal learning. Participants also acknowledged the decision aid’s neutral stance regarding the pursuit of fertility preservation interventions. Overall, TNB youth/young adults and their parents found AFFRMED to be approachable and appreciated the informative and friendly tone.

Design elements suggested by participants. (A) An audio button for listening to text. In the final prototype, audio was recorded by one of the participants. (B) A notepad feature at the bottom right hand corner gives users a space to jot down questions as they progress throughout the learning modules. (C) A decision-making prompt where users can reflect on their thoughts regarding the process of fertility preservation.

Showing the evolution of AFFRMED. (A) and (B) shows the evolution of individual chapter summaries. (C) and (D) show the evolution of the final wrap-up page. As shown in (D), in the final version, users can download chapter summaries along with notes and questions they have jotted down at the very end of the module. Such chapter summaries and notes can be emailed or saved onto users’ computers.

Participants also identified areas for improvement, some of which are limited by the current state of the science. For instance, among TNB youth/young adults, more concrete guidance was desired regarding how long someone would need to temporarily discontinue GAH to pursue fertility preservation if they had already started GAH and the specific dose or duration of time on GAH that would permanently impair fertility. Among parents, more specific and technical information was desired about how long side effects of ovarian stimulation may be observed. A parent of a younger GnRHa cohort youth also expressed concern that the decision aid content, despite attempts to simplify language, may still be overwhelming to a child. Further qualitative data supporting the overall positive response with further suggestions regarding the content and design of AFFRMED are depicted in Table 2. Final design elements, imagery, and chapter summaries are highlighted in online supplementary Table S3.

Co-design sessions: representative illustrative quotations about AFFRMED by parents and youth/young adults.

| Content area . | Quote(s) . |

|---|---|

| Presentation of content | “This is great. Maybe this could be something I go through with my kid. Or could go through it separately but then talk about it.” (Parent of 11-year-old trans girl) |

| “One thing I appreciate is that it helps me talk to my kid about anatomy without using gender. This does a great job of doing that. This isn’t natural language to me so it’s helpful to have this as a guide.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “Growing up, we didn’t even cover the basics of puberty in school. So this is good for people who didn’t get that information. It is a difficult topic that is hard to depict. But if you’re deciding to look at this decision aid, you know what you’re getting into.” (23-year-old trans man) | |

| Visual aesthetics | “I like that colors and associated body parts are consistent. It helps explain what you are looking at.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I like the pictures. I see some ovaries, a uterus and some testicles.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| “Someone’s taking testosterone and growing a beard. His voice got deeper, and his ovaries are decreasing.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| Ease of use | “When you have pictures that are more realistic, there’s a tendency to glaze over that. This is like, I’m friendly, happy. I like that for a kid who’s 7 or 8 or exploring about this, they’re getting hit with sex education which is so dry so this is more conducive to any kid. Even as adult I’m attracted to more animated images.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) |

| “I really like it. Having a way to have info presented nicely, not just scouring the internet and it’s right here and interactive and audiovisual, will make a big a difference.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| Overall impression | “Overall it wasn’t pushing you to do fertility preservation. It was neutral and unbiased. It presented the two options and what could come out of each option.” (Parent of 13-year-old trans boy) |

| “I like that you show the different options for having children other than biologically having them and show the pros and cons of adopting and fostering. You also clarified that this decision is difficult and that it is ok whatever decision you make and okay to change your mind.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| “I can see this being offered to me during my first few clinic appointments.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| Tone of decision aid | “The tone was gender-friendly, serious but approachable and friendly.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I really like the tone. You have done an amazing job of getting a lot of info into simple, user-friendly language. This isn’t easy content to bring to that level concreteness. Great work.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “The tone is informative and friendly, a tone of allyship.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| “The tone was definitely not biased. If you do not want to have children or pursue fertility preservation, that’s ok.” (14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| Areas for improvement | “I’d want to know other side effects [of ovarian stimulation hormone shots], and how long that would last. It’s not just 2 weeks and you go back to whatever. When could they resume cross hormones?” (Parent of 12-year-old boy) |

| “This is definitely lost on a 7- or 8-year-old. It’s a lot of stuff. Great for a parent who wants to know all the steps but for a kid it’s overwhelming. The language is still trying to be simplistic but this is all…a kid would be overwhelmed.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I have questions about if the amount of time on gender-affirming hormones might affect the procedure [for fertility preservation]. Like if taking for a few years, would it be possible to preserve?” (20-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I would have questions about stopping hormones [to pursue fertility preservation] … The idea of losing progress and hormone levels returning to levels when starting hormones… How long would someone have to stop if they were preserving fertility?” (20-year-old genderqueer person) |

| Content area . | Quote(s) . |

|---|---|

| Presentation of content | “This is great. Maybe this could be something I go through with my kid. Or could go through it separately but then talk about it.” (Parent of 11-year-old trans girl) |

| “One thing I appreciate is that it helps me talk to my kid about anatomy without using gender. This does a great job of doing that. This isn’t natural language to me so it’s helpful to have this as a guide.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “Growing up, we didn’t even cover the basics of puberty in school. So this is good for people who didn’t get that information. It is a difficult topic that is hard to depict. But if you’re deciding to look at this decision aid, you know what you’re getting into.” (23-year-old trans man) | |

| Visual aesthetics | “I like that colors and associated body parts are consistent. It helps explain what you are looking at.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I like the pictures. I see some ovaries, a uterus and some testicles.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| “Someone’s taking testosterone and growing a beard. His voice got deeper, and his ovaries are decreasing.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| Ease of use | “When you have pictures that are more realistic, there’s a tendency to glaze over that. This is like, I’m friendly, happy. I like that for a kid who’s 7 or 8 or exploring about this, they’re getting hit with sex education which is so dry so this is more conducive to any kid. Even as adult I’m attracted to more animated images.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) |

| “I really like it. Having a way to have info presented nicely, not just scouring the internet and it’s right here and interactive and audiovisual, will make a big a difference.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| Overall impression | “Overall it wasn’t pushing you to do fertility preservation. It was neutral and unbiased. It presented the two options and what could come out of each option.” (Parent of 13-year-old trans boy) |

| “I like that you show the different options for having children other than biologically having them and show the pros and cons of adopting and fostering. You also clarified that this decision is difficult and that it is ok whatever decision you make and okay to change your mind.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| “I can see this being offered to me during my first few clinic appointments.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| Tone of decision aid | “The tone was gender-friendly, serious but approachable and friendly.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I really like the tone. You have done an amazing job of getting a lot of info into simple, user-friendly language. This isn’t easy content to bring to that level concreteness. Great work.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “The tone is informative and friendly, a tone of allyship.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| “The tone was definitely not biased. If you do not want to have children or pursue fertility preservation, that’s ok.” (14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| Areas for improvement | “I’d want to know other side effects [of ovarian stimulation hormone shots], and how long that would last. It’s not just 2 weeks and you go back to whatever. When could they resume cross hormones?” (Parent of 12-year-old boy) |

| “This is definitely lost on a 7- or 8-year-old. It’s a lot of stuff. Great for a parent who wants to know all the steps but for a kid it’s overwhelming. The language is still trying to be simplistic but this is all…a kid would be overwhelmed.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I have questions about if the amount of time on gender-affirming hormones might affect the procedure [for fertility preservation]. Like if taking for a few years, would it be possible to preserve?” (20-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I would have questions about stopping hormones [to pursue fertility preservation] … The idea of losing progress and hormone levels returning to levels when starting hormones… How long would someone have to stop if they were preserving fertility?” (20-year-old genderqueer person) |

Note. For gender descriptors, we used terms self-reported by participants.

Co-design sessions: representative illustrative quotations about AFFRMED by parents and youth/young adults.

| Content area . | Quote(s) . |

|---|---|

| Presentation of content | “This is great. Maybe this could be something I go through with my kid. Or could go through it separately but then talk about it.” (Parent of 11-year-old trans girl) |

| “One thing I appreciate is that it helps me talk to my kid about anatomy without using gender. This does a great job of doing that. This isn’t natural language to me so it’s helpful to have this as a guide.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “Growing up, we didn’t even cover the basics of puberty in school. So this is good for people who didn’t get that information. It is a difficult topic that is hard to depict. But if you’re deciding to look at this decision aid, you know what you’re getting into.” (23-year-old trans man) | |

| Visual aesthetics | “I like that colors and associated body parts are consistent. It helps explain what you are looking at.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I like the pictures. I see some ovaries, a uterus and some testicles.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| “Someone’s taking testosterone and growing a beard. His voice got deeper, and his ovaries are decreasing.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| Ease of use | “When you have pictures that are more realistic, there’s a tendency to glaze over that. This is like, I’m friendly, happy. I like that for a kid who’s 7 or 8 or exploring about this, they’re getting hit with sex education which is so dry so this is more conducive to any kid. Even as adult I’m attracted to more animated images.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) |

| “I really like it. Having a way to have info presented nicely, not just scouring the internet and it’s right here and interactive and audiovisual, will make a big a difference.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| Overall impression | “Overall it wasn’t pushing you to do fertility preservation. It was neutral and unbiased. It presented the two options and what could come out of each option.” (Parent of 13-year-old trans boy) |

| “I like that you show the different options for having children other than biologically having them and show the pros and cons of adopting and fostering. You also clarified that this decision is difficult and that it is ok whatever decision you make and okay to change your mind.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| “I can see this being offered to me during my first few clinic appointments.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| Tone of decision aid | “The tone was gender-friendly, serious but approachable and friendly.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I really like the tone. You have done an amazing job of getting a lot of info into simple, user-friendly language. This isn’t easy content to bring to that level concreteness. Great work.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “The tone is informative and friendly, a tone of allyship.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| “The tone was definitely not biased. If you do not want to have children or pursue fertility preservation, that’s ok.” (14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| Areas for improvement | “I’d want to know other side effects [of ovarian stimulation hormone shots], and how long that would last. It’s not just 2 weeks and you go back to whatever. When could they resume cross hormones?” (Parent of 12-year-old boy) |

| “This is definitely lost on a 7- or 8-year-old. It’s a lot of stuff. Great for a parent who wants to know all the steps but for a kid it’s overwhelming. The language is still trying to be simplistic but this is all…a kid would be overwhelmed.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I have questions about if the amount of time on gender-affirming hormones might affect the procedure [for fertility preservation]. Like if taking for a few years, would it be possible to preserve?” (20-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I would have questions about stopping hormones [to pursue fertility preservation] … The idea of losing progress and hormone levels returning to levels when starting hormones… How long would someone have to stop if they were preserving fertility?” (20-year-old genderqueer person) |

| Content area . | Quote(s) . |

|---|---|

| Presentation of content | “This is great. Maybe this could be something I go through with my kid. Or could go through it separately but then talk about it.” (Parent of 11-year-old trans girl) |

| “One thing I appreciate is that it helps me talk to my kid about anatomy without using gender. This does a great job of doing that. This isn’t natural language to me so it’s helpful to have this as a guide.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “Growing up, we didn’t even cover the basics of puberty in school. So this is good for people who didn’t get that information. It is a difficult topic that is hard to depict. But if you’re deciding to look at this decision aid, you know what you’re getting into.” (23-year-old trans man) | |

| Visual aesthetics | “I like that colors and associated body parts are consistent. It helps explain what you are looking at.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I like the pictures. I see some ovaries, a uterus and some testicles.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| “Someone’s taking testosterone and growing a beard. His voice got deeper, and his ovaries are decreasing.” (10-year-old trans boy) | |

| Ease of use | “When you have pictures that are more realistic, there’s a tendency to glaze over that. This is like, I’m friendly, happy. I like that for a kid who’s 7 or 8 or exploring about this, they’re getting hit with sex education which is so dry so this is more conducive to any kid. Even as adult I’m attracted to more animated images.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) |

| “I really like it. Having a way to have info presented nicely, not just scouring the internet and it’s right here and interactive and audiovisual, will make a big a difference.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| Overall impression | “Overall it wasn’t pushing you to do fertility preservation. It was neutral and unbiased. It presented the two options and what could come out of each option.” (Parent of 13-year-old trans boy) |

| “I like that you show the different options for having children other than biologically having them and show the pros and cons of adopting and fostering. You also clarified that this decision is difficult and that it is ok whatever decision you make and okay to change your mind.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| “I can see this being offered to me during my first few clinic appointments.” (16-year-old boy) | |

| Tone of decision aid | “The tone was gender-friendly, serious but approachable and friendly.” (Parent of 16-year-old boy) |

| “I really like the tone. You have done an amazing job of getting a lot of info into simple, user-friendly language. This isn’t easy content to bring to that level concreteness. Great work.” (Parent of 10-year-old child) | |

| “The tone is informative and friendly, a tone of allyship.” (21-year-old trans woman) | |

| “The tone was definitely not biased. If you do not want to have children or pursue fertility preservation, that’s ok.” (14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| Areas for improvement | “I’d want to know other side effects [of ovarian stimulation hormone shots], and how long that would last. It’s not just 2 weeks and you go back to whatever. When could they resume cross hormones?” (Parent of 12-year-old boy) |

| “This is definitely lost on a 7- or 8-year-old. It’s a lot of stuff. Great for a parent who wants to know all the steps but for a kid it’s overwhelming. The language is still trying to be simplistic but this is all…a kid would be overwhelmed.” (Parent of 14-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I have questions about if the amount of time on gender-affirming hormones might affect the procedure [for fertility preservation]. Like if taking for a few years, would it be possible to preserve?” (20-year-old nonbinary person) | |

| “I would have questions about stopping hormones [to pursue fertility preservation] … The idea of losing progress and hormone levels returning to levels when starting hormones… How long would someone have to stop if they were preserving fertility?” (20-year-old genderqueer person) |

Note. For gender descriptors, we used terms self-reported by participants.

Usability testing interviews

Participants

Nine youth/young adults and six parents completed individual usability testing interviews. Youth/young adult participants ranged in age from 8 to 23 years, M(SD) = 14.89 (5.06). Parent participants ranged in age from 35 to 52 years, M(SD) = 43.67 (7.50). Table 1 presents demographic information. Five youth/young adults interested in or actively taking GAH, four youth interested in or actively taking GnRHa, two parents of youth/young adults interested in or actively taking GAH, and four parents of youth interested in or actively taking GnRHa participated.

Measures of acceptability, appropriateness, usability, and satisfaction

Mean ASQ scores for youth/young adult participants across treatment cohorts was 3.39 (SD = 2.60), and for parents was 1.94 (SD = 1.16). ASQ scores for youth in the GnRHa cohort [M(SD) = 4.88 (1.78)] were higher than for youth/young adults in the GAH cohort [M(SD) = 2.20 (2.68)], indicating lower satisfaction among GnRHa cohort youth. ASQ scores among parents of youth in the GnRHa cohort [M(SD) = 1.75 (0.96)] were lower than for parents of youth/young adults in the GAH cohort [M(SD) = 2.33 (1.89), indicating higher satisfaction among parents of youth in the GnRHa cohort. Parents reported greater satisfaction with the ease of completing AFFRMED tasks, the amount of time needed to complete tasks, and the support information available while completing AFFRMED tasks compared to youth/young adults.

Mean NPS score for youth/young adult participants was 55.6, and for parents was 66.6, indicating a high likelihood that all participants would recommend AFFRMED to others. Among youth/young adults, 77.8% of responses were in the “Promoter” category, and 22.2% were in the “Detractor” category. Among parents, 83.3% of responses were “Promoters” and 16.7% were in the “Detractor” category. No participant scores fell within the “Passive” category. When examining NPS scores by treatment cohort, the mean score among youth in the GnRHa cohort was 0, and among youth/young adults in the GAH cohort was 100. The mean NPS score among parents of youth in the GnRHa was 50, and among parents of youth/young adults in the GAH cohort was 100. Across the 15 usability testing participants, only 3 were “Detractors” (2 GnRHa cohort youth and 1 parent of a GnRHa cohort youth).

The overall mean SUS score among youth/young adult participants was 75.00 (SD = 20.77), and among parent participants was 83.75 (SD = 19.80). Both groups (i.e., youth/young adults and parents) reported mean SUS scores higher than the average SUS score of 68 (Brooke, 1996; Hyzy et al., 2022). Youth in the GnRHa cohort had a lower mean SUS score: M(SD) = 58.13 (20.55), compared to youth/young adults in the GAH cohort: M(SD) = 88.50 (5.76). Similarly, parents of GnRHa cohort youth had lower mean SUS scores: M(SD) = 76.88 (21.54), compared to parents of GAH cohort youth: M(SD) = 97.50 (0.00). One youth participant skipped a single item on the measure. There were no significant differences between mean SUS scores when using imputation methods to address missing data versus dropping the case, so we reported results with imputation for parsimony.

Discussion

This study describes the iterative process of engaging end users in co-designing and co-developing a web-based fertility-related decision aid targeted at TNB youth and young adults and their parents. Overall, TNB youth/young adults and their parents found AFFRMED to be informative, accessible, and relevant in the context of decision-making about gender-affirming medical treatment that has the potential to impair long-term fertility. Decision aid acceptability, usability, and satisfaction were strong across youth/young adult and parent participants, although some variability across treatment cohorts was observed.

A common strength of AFFRMED identified by youth, young adults, and parents was the accessibility of reliable information in one resource. Participants in all co-design sessions reported learning something new and/or expressed interest in using this decision aid in their own medical decision-making processes. With respect to AFFRMED content, participants appreciated the use of non-gendered language to provide education about human anatomy, reproduction, and fertility preservation. Parents noted that the decision aid provided a model for having ongoing discussions with their younger children about a complex topic using affirming language. The neutral stance regarding the pursuit of fertility preservation interventions was also highlighted as critical for a tool intended to facilitate patient education and shared decision-making. Indeed, previous research has reported negative experiences among TNB youth/young adults who felt pressured by parents or healthcare providers to pursue fertility preservation interventions (Chen et al., 2019b).

GAH cohort youth/young adults and parents of GAH cohort youth/young adults endorsed the highest ratings across metrics of perceived usability and satisfaction with AFFRMED, as well as the overall likelihood of recommending AFFRMED to a friend. In contrast, GnRHa cohort youth and parents of GnRHa cohort youth identified the most opportunities for improvement. It is possible that the skewed sample with respect to treatment cohort among TNB youth/young adults from the initial co-design sessions—4 GnRHa cohort youth vs. 12 GAH cohort youth/young adults participated—may have contributed to these patterns of findings. In addition, the lower bound for the age of participants in the co-design sessions was 10 years, compared to 8 years for usability testing interviews, which also may have contributed to lower usability ratings among GnRHa cohort youth. It is also possible that the GnRHa cohort youths’ chronologically younger age and less developmental maturity relative to GAH cohort youth/young adults resulted in more difficulty comprehending and weighing complex treatment decisions. This interpretation is consistent with clinicians working with TNB youth who regularly identify youths’ developmental stage as a barrier to fertility counseling and fertility preservation decision-making (Tishelman et al., 2019).

Digital decision aids offer opportunities to augment clinician-delivered fertility counseling and have the potential to address service gaps related to limited face-to-face time and documented provider-level barriers related to knowledge and comfort counseling TNB youth about fertility (Chen et al., 2019a; Tishelman et al., 2019). Utilizing human-centered design strategies in intervention development and involving end users as co-creators in healthcare innovation increases the likelihood for implementation uptake and scalability. We co-designed AFFRMED with TNB youth/young adults and their parents, which is now ready for efficacy testing. Key next steps include testing AFFRMED’s effect on fertility-related knowledge and decisional self-efficacy, which are hypothesized mechanisms for improving decision satisfaction.

This study has strengths. It is the first to engage TNB youth/young adults and their parents as end users in human-centered design to co-create an educational and decision support tool to facilitate complex medical decisions about fertility and fertility preservation. We contend the significance of using human-centered design in behavioral health research is the potential for making innovation more equitable and shedding light on the historical power difference between “researchers” and “participants.” By enabling end users to be co-creators in healthcare innovations, individuals who are directly impacted by the intervention can play an active role in the design process, thereby designing for implementation from the outset. Furthermore, the study design enabled us to qualitatively and quantitatively assess perceptions of AFFRMED. The study also engaged a large number of TNB youth/young adults and their parents to inform decision aid content and navigability to ensure a patient-centered website.

This study has limitations. We recruited locally from our subspecialty gender health clinic, and thus, the demographic characteristics of our sample, while consistent with clinic demographics, are not representative of the broader population of TNB youth in the United States (Herman et al., 2022). Specifically, TNB youth/young adults were disproportionally designated female at birth across co-design sessions and usability testing interviews and non-Latinx/e White for co-design sessions. Parents were highly educated; all but one parent participant across design sessions and usability testing interviews had earned either a college or advanced degree. Parent participants were also mostly designated female at birth. Thus, it is not clear whether perceptions of usability would hold for parents with less formal educational histories or for fathers.

AFFRMED is a patient-centered interactive website about fertility and fertility preservation targeted to TNB youth/young adults and their parents to support informed treatment decision-making. Future research should evaluate whether the use of AFFRMED can effectively increase fertility and fertility preservation knowledge, and self-efficacy in the context of fertility decision-making, and enhance informed decision-making.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at Journal of Pediatric Psychology (https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/jpepsy/)

Author contributions

Diane Chen (Conceptualization [lead], Formal analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [lead], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [lead], Supervision [lead], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Elaine Shen (Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Visualization [lead], Writing—original draft-Supporting, Writing—review & editing [equal]), Victoria D. Kolbuck (Data curation [lead], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Writing—original draft-Supporting, Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Afiya Sajwani (Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Courtney Finlayson (Conceptualization [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), and Elisa J. Gordon (Conceptualization [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Supervision [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting])

Funding

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number R21 HD097459).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.