-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joonho Ahn, Dong-Wook Lee, Jaesung Choi, Mo-Yeol Kang, Who is the most precarious among the nonstandard workers? A comparative study of unmet medical needs among standard workers and subtypes of nonstandard workers, Journal of Occupational Health, Volume 65, Issue 1, January/December 2023, e12414, https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12414

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Nonstandard workers might have a relatively higher risk of unmet medical needs than standard workers. This study subdivided nonstandard workers to investigate the effects of nonstandard employment on unmet medical needs.

We used the Korea Health Panel 2011–2018 data. The independent variable, employment contract, was defined using the nonstandard form described by the ILO: Temporary workers, Part-time workers, and Temporary agent workers. The analytical method used in this study was a panel logit model that accounted for repeated measured participants. By controlling for time-invariant individual-fixed effects, we investigate the relationship between subdivided nonstandard work and the risk of unmet medical needs with reference to standard work.

The results of the analysis clearly showed that compared with standard workers, temporary agency workers had a significantly higher risk of unmet medical needs (Odds ratio = 1.182, 95% CI = 1.016–1.374). The main cause of this phenomenon was economic reasons in this group.

This study found that temporary agency workers in the general Korean population have a significantly higher risk of unmet healthcare needs. The result of this study implies that financial hardship might be a fundamental health hazard among workers with nonstandard employment.

INTRODUCTION

Since the late 1970s, globalization, neo-liberalism, and deindustrialization have minimized government interference and labor market rules and maximized global-free trade competitiveness. This trend has led to the continuous promotion of a more flexible workforce, both globally and locally, which eventually destabilizes employment. Unfortunately, unstable employment conditions are associated with low wages, poor working conditions, and weakened worker rights, leading to worsening health.1 Workers with precarious employment have a high risk of accidents at work2; a high frequency of harmful health behaviors, such as excessive drinking or smoking; and a lack of health care for prevention.3 Therefore, nonstandard workers might have a relatively higher risk of unmet medical needs than standard workers.

Access to affordable health services of decent quality is a key social determinant of health for all and a critical component of the approach to advancing health equity.4 Unmet medical need is defined as follows: “the subject does not receive healthcare services even when the subject wants or determines to need.” It is an important indicator for evaluating accessibility to healthcare services.5

Given the increase in precarious employment and the interest in social determinants of health, recent studies have attempted to investigate the level of accessibility to medical services that might affect workers’ health levels by determining the size and status of unmet medical needs. According to a study conducted in Sweden, exposure to precarious employment in 1999/2000 was associated with unmet needs for health care in 2010 (odds ratio [OR], 1.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51–2.11).6 Similarly, Lee et al. reported that although 9.2% of standard workers experienced unmet medical needs for economic reasons, 26.5% of temporary workers and 45.5% of daily workers experienced unmet medical needs for economic reasons, indicating that the more unstable the employment status, the higher the risk of unmet medical needs.7 The main reason for this phenomenon may be that social protection systems, such as paid sick leave, and unemployment insurance for workers with precarious employment, are not sufficiently established. Therefore, despite poor health conditions, there is no other option to select unemployment and income loss or leave medical needs unmet.

Thus, employment instability is a critical factor affecting unmet medical needs. However, in previous studies, only a simple classification of employment status was used, without analyzing the complex and diverse dimensions of precarious employment. The International Labor Organization (ILO) report addresses four types of nonstandard employment: (1) temporary employment, (2) part-time work, (3) temporary agency work and other forms of employment involving multiple parties, and (4) disguised employment relationships and dependent self-employment.8 As there are different characteristics across types of nonstandard employment, it seems that there are more vulnerable groups among them.

However, no studies have identified the risk of unmet medical needs by comparing the different aspects of nonstandard employment proposed by the ILO. Thus, this study subdivided nonstandard workers to investigate the effects of nonstandard employment on unmet medical needs. Moreover, since previous studies reported that unmet medical care shows different patterns according to gender,9 a gender-stratified analysis was performed for the association between nonstandard employment and unmet medical needs.

METHODS

Study participants

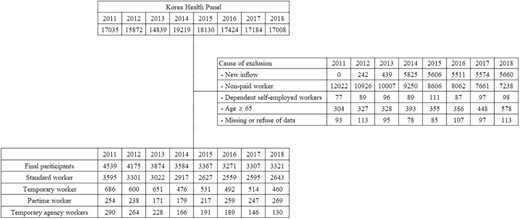

We used the Korea Health Panel (KHP) data collected by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs and National Health Insurance Service. The KHP is the first medical panel survey in Korea that surveys the same 7000–8000 households annually on their medical use behaviors and medical expenses.10 It is a nationally representative survey conducted through stratified, multi-stage cluster sampling (nationally approved statistics no. 920012). KHP data were released from 2008 to 2018, but information on unmet medical needs was continuously surveyed from 2011; therefore, we used the 2011–2018 data. The KHP has a new inflow due to birth, adoption, and marriage, and large-sized new inflows occur as new households were included in the participants to compensate for the continuous dropout in 2012. However, new inflows were excluded from this study (Figure 1). Among them, we excluded nonpaid workers, those with missing or refusing occupational information, and those receiving hospital treatment. Additionally, this analysis focused mainly on employees; therefore, independent and self-employed workers were also excluded. The final number of participants ranged from 4539 in 2011 to 3321 in 2018.

Variable measurement

The independent variable, employment contract, was defined using the nonstandard form described by the ILO.8 Employment contracts were defined using the answers to the following three questions: “Did you work full-time or part-time?” “Does your job have a fixed contract period?” and “Which of the following is your current employment relationship?” Part-time workers were classified on the basis of their responses. Participants with fixed contract periods were defined as temporary workers. Answers to the question about current employment relationships included direct contract and temporary agency workers. According to this answer, temporary agent workers were defined. Finally, workers with nonfixed-term contracts, full-time work, and direct contract employment were defined as standard workers.

The dependent variable was an unmet medical need, which was evaluated using the following question: “In the past year, have you ever needed to receive treatment or an examination (excluding dental treatment and examination) at a hospital but did not get it?” If the answer was “Yes, I did not receive it at least once,” it was considered an unmet medical need.

Variables related to sociodemographic characteristics included gender, age, educational level, and health status. Educational level was divided into “high school or below” and “college or above.” Because subjective health perception has been universally used as a proxy for actual health status, health status variables were defined using subjective health perception variables.11 When asked “How your health in general is,” the participant who responded “very good,” “good,” or “normal” was considered to have good health status. Conversely, the participant who responded “bad” or “very bad” was considered to have poor health status.12 Occupations were classified into three main categories according to the Korean Standard Classification of Occupations: office workers (managers, professionals, and related workers and clerks), service and sales workers (service workers and sales workers), and manual workers (craft and related trade, equipment, machine operating and assembling, and elementary workers).13

Statistical analyses

The general characteristics of the study participants were summarized using employment contracts. The main analysis was performed in two ways. In the primary analysis, we identified the risk of each of the three nonstandard worker groups compared with that of the standard worker group (temporary worker vs. standard worker, part-time worker vs. standard worker, temporary agency worker vs. standard worker). As a supplementary analysis, each of the three nonstandard workers was compared with each group using opposite concepts (temporary vs. permanent, part-time vs. full-time, temporary agency worker vs. direct contract workers). This study used a panel logit model with fixed effects. A panel logit model is a statistical model used when the dependent variable is a binary variable in longitudinal or panel data. This model is commonly used in panel data analyses, in which entities, such as individuals, households, or firms, have data measured repeatedly over a certain period. Unobservable individual effects and occupational agents can cause endogeneity problems, but these can be mitigated using panel data.14 Time-invariant individual effects were controlled through a panel analysis to identify the association between unmet medical needs and the employment contract. Additionally, the fixed effects model considers individual differences and mitigates the healthy worker effect.15

To select variables for adjustment, a directed acyclic graph (DAG) was used in the model with DAGitty to draw causal diagrams.16 The adjustment variables proposed using DAGitty were age, gender, and educational level (Figure S1). In addition, the risk of unmet medical needs for specific reasons among workers who experienced unmet medical needs was evaluated. In the group with unmet medical needs, the analysis was performed using various specific reasons for unmet medical needs as outcomes. In the sensitivity analysis, the population who answered “I never needed treatment or examination” was excluded. Data were analyzed using the SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.). The two-tailed P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participants’ characteristics

Table S1 shows the characteristics of the participants in 2011–2018 according to employment contracts. Standard workers were the most common, whereas temporary workers were the most common nonstandard workers. Among standard workers, the proportion of men was higher than that of women, whereas among nonstandard workers (temporary, part-time, and temporary agency workers), the proportion of women was lower than that of men. The average age of standard workers was higher than that of nonstandard workers. The proportion of standard workers with a poor health status was higher than that of nonstandard workers. Among standard workers, office workers were the most common, and manual workers were the most common among temporary and temporary agency workers.

Association between employment contracts and unmet medical needs

As the primary analysis, the risks of unmet medical needs of three nonstandard workers (temporary, part-time, and temporary agency workers) were estimated and compared with standard workers (Table 1). When standard workers were the reference group, only temporary agency workers among nonstandard workers showed a significant increase in the risk of unmet medical needs (adjusted OR, 1.173; 95% CI, 1.004–1.369). Table S2 presents the stratified analysis according to gender. The male subgroup showed a significant increase in risk, whereas this was not observed in females. Compared with standard workers, temporary agency workers had a higher risk of unmet medical needs, particularly among males (adjusted OR, 1.408; 95% CI, 1.136–1.745).

Crude OR and adjusted OR of unmet medical needs in accordance with employment contracts.

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Standard worker | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary worker | 1.084 (0.979–1.200) | 1.005 (0.906–1.115) |

| Part-time workers | 1.099 (0.949–1.273) | 0.976 (0.841–1.132) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.325 (1.143–1.536)* | 1.182 (1.016–1.374)* |

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Standard worker | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary worker | 1.084 (0.979–1.200) | 1.005 (0.906–1.115) |

| Part-time workers | 1.099 (0.949–1.273) | 0.976 (0.841–1.132) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.325 (1.143–1.536)* | 1.182 (1.016–1.374)* |

Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using a panel logit model with fixed effects after adjusting for gender, age, and educational levels.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant results.

Crude OR and adjusted OR of unmet medical needs in accordance with employment contracts.

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Standard worker | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary worker | 1.084 (0.979–1.200) | 1.005 (0.906–1.115) |

| Part-time workers | 1.099 (0.949–1.273) | 0.976 (0.841–1.132) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.325 (1.143–1.536)* | 1.182 (1.016–1.374)* |

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Standard worker | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary worker | 1.084 (0.979–1.200) | 1.005 (0.906–1.115) |

| Part-time workers | 1.099 (0.949–1.273) | 0.976 (0.841–1.132) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.325 (1.143–1.536)* | 1.182 (1.016–1.374)* |

Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using a panel logit model with fixed effects after adjusting for gender, age, and educational levels.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant results.

As a secondary analysis, the risk of unmet medical needs of the three nonstandard workers, compared with each group with opposite concepts, was identified (Table 2). Temporary agency workers had a significantly higher risk of unmet medical needs compared with direct contract workers (adjusted OR, 1.215; 95% CI, 1.045–1.413). The gender-stratified analysis is presented in Table S2. According to the findings, a significant increase in risk was observed in the male subgroup, whereas there was no such increase observed in females. The risk of unmet medical needs was higher among male temporary agency workers than among male nontemporary agency workers (adjusted OR, 1.376; 95% CI, 1.115–1.690; Table S3). Similarly, the risk of unmet medical needs was higher among female temporary agency workers than among female nontemporary agency workers (adjusted OR, 1.109; 95% CI, 0.904–1.360).

Risk for unmet medical needs of the three nonstandard workers was compared with every three groups with opposite concepts.

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Permanent workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary workers | 1.089 (0.942–1.258) | 0.993 (0.859–1.148) |

| Full-time workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Part-time workers | 1.070 (0.966–1.184) | 0.998 (0.901–1.106) |

| Direct contract workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.334 (1.154–1.543)* | 1.226 (1.058–1.420)* |

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Permanent workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary workers | 1.089 (0.942–1.258) | 0.993 (0.859–1.148) |

| Full-time workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Part-time workers | 1.070 (0.966–1.184) | 0.998 (0.901–1.106) |

| Direct contract workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.334 (1.154–1.543)* | 1.226 (1.058–1.420)* |

Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using a panel logit model with fixed effects after adjusting for gender, age, and educational levels.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant results.

Risk for unmet medical needs of the three nonstandard workers was compared with every three groups with opposite concepts.

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Permanent workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary workers | 1.089 (0.942–1.258) | 0.993 (0.859–1.148) |

| Full-time workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Part-time workers | 1.070 (0.966–1.184) | 0.998 (0.901–1.106) |

| Direct contract workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.334 (1.154–1.543)* | 1.226 (1.058–1.420)* |

| . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Permanent workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary workers | 1.089 (0.942–1.258) | 0.993 (0.859–1.148) |

| Full-time workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Part-time workers | 1.070 (0.966–1.184) | 0.998 (0.901–1.106) |

| Direct contract workers | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Temporary agency workers | 1.334 (1.154–1.543)* | 1.226 (1.058–1.420)* |

Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using a panel logit model with fixed effects after adjusting for gender, age, and educational levels.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant results.

Additionally, the specific reasons for the unmet medical needs were analyzed as outcomes in the group with unmet medical needs (Table 3). Significantly increased risks of economic reasons were found for all nonstandard workers, whereas significantly decreased risks of insufficient time were found for all nonstandard workers. Among the three nonstandard workers, the risk of economic reasons was the greatest among temporary workers (adjusted OR, 1.753; 95% CI, 1.280–2.400), whereas the risk of insufficient time was the smallest (adjusted OR, 0.476; 95% CI, 0.361–0.628) among part-time workers.

Risk of unmet medical needs by specific reason among the workers experienced unmet medical needs.

| Specific reasons for unmet medical needs . | Temporary workersa (vs. Permanent workers) . | Part-time workersa (vs. Full-time workers) . | Temporary agency workersa (vs. Direct contract workers) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic reasons | 1.416 (1.130–1.776)* | 1.753 (1.280–2.400)* | 1.643 (1.200–2.251)* |

| Mild symptom | 0.970 (0.794–1.186) | 1.359 (1.020–1.811)* | 1.120 (0.839–1.496) |

| Insufficient time | 0.833 (0.695–0.997)* | 0.476 (0.361–0.628)* | 0.705 (0.541–0.918)* |

| Othersb | 0.958 (0.654–1.405) | 1.517 (0.941–2.445) | 0.326 (0.132–0.803)* |

| Specific reasons for unmet medical needs . | Temporary workersa (vs. Permanent workers) . | Part-time workersa (vs. Full-time workers) . | Temporary agency workersa (vs. Direct contract workers) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic reasons | 1.416 (1.130–1.776)* | 1.753 (1.280–2.400)* | 1.643 (1.200–2.251)* |

| Mild symptom | 0.970 (0.794–1.186) | 1.359 (1.020–1.811)* | 1.120 (0.839–1.496) |

| Insufficient time | 0.833 (0.695–0.997)* | 0.476 (0.361–0.628)* | 0.705 (0.541–0.918)* |

| Othersb | 0.958 (0.654–1.405) | 1.517 (0.941–2.445) | 0.326 (0.132–0.803)* |

Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using a panel logit model with fixed effects after adjusting for gender, age, and educational levels.

Others: distance from medical institutions, discomfort in movement, no one can take care of their child, lack of information, difficulty in doctor appointments.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant results.

Risk of unmet medical needs by specific reason among the workers experienced unmet medical needs.

| Specific reasons for unmet medical needs . | Temporary workersa (vs. Permanent workers) . | Part-time workersa (vs. Full-time workers) . | Temporary agency workersa (vs. Direct contract workers) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic reasons | 1.416 (1.130–1.776)* | 1.753 (1.280–2.400)* | 1.643 (1.200–2.251)* |

| Mild symptom | 0.970 (0.794–1.186) | 1.359 (1.020–1.811)* | 1.120 (0.839–1.496) |

| Insufficient time | 0.833 (0.695–0.997)* | 0.476 (0.361–0.628)* | 0.705 (0.541–0.918)* |

| Othersb | 0.958 (0.654–1.405) | 1.517 (0.941–2.445) | 0.326 (0.132–0.803)* |

| Specific reasons for unmet medical needs . | Temporary workersa (vs. Permanent workers) . | Part-time workersa (vs. Full-time workers) . | Temporary agency workersa (vs. Direct contract workers) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic reasons | 1.416 (1.130–1.776)* | 1.753 (1.280–2.400)* | 1.643 (1.200–2.251)* |

| Mild symptom | 0.970 (0.794–1.186) | 1.359 (1.020–1.811)* | 1.120 (0.839–1.496) |

| Insufficient time | 0.833 (0.695–0.997)* | 0.476 (0.361–0.628)* | 0.705 (0.541–0.918)* |

| Othersb | 0.958 (0.654–1.405) | 1.517 (0.941–2.445) | 0.326 (0.132–0.803)* |

Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using a panel logit model with fixed effects after adjusting for gender, age, and educational levels.

Others: distance from medical institutions, discomfort in movement, no one can take care of their child, lack of information, difficulty in doctor appointments.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant results.

Significantly increased risk of mild symptoms (adjusted OR, 1.359; 95% CI, 1.020–1.811) was observed in part-time workers only. For sensitivity analysis, the same analyses were performed except for the population who answered “I have never needed treatment or examination,” and the results were similar to those of the overall population (Table S4).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the risk of unmet medical needs for nonstandard workers was examined and divided into three aspects. A significant difference was shown only between “Standard workers” and “Temporary agency workers,” and the differences between standard workers and the other nonstandard workers were not significant.

This result builds upon past evidence highlighting inequalities in the experience of unmet medical needs depending on employment type.17 For instance, Ha et al. reported that standard workers had a 13.3% chance of experiencing unmet medical needs, whereas nonstandard workers had an unmet medical needs experience rate of 20.7%, indicating that nonstandard workers experience more unmet medical needs than standard workers.18

An analysis of the specific reasons revealed that the main cause of unmet medical care was economic among all nonstandard workers. In particular, the ratio of unmet medical care needs for economic reasons was relatively large for temporary agency workers, and the gap was relatively small among temporary workers. In the case of part-time workers, the gap in unmet medical care due to a lack of time was significantly larger compared with that of full-time workers, offsetting the gap due to economic reasons, and mild symptoms were more prevalent among them. Temporary workers also had a small gap due to unmet medical care and lack of time, partially offsetting the gap for economic reasons. However, temporary agency workers had a large gap in unmet medical care for economic reasons, but the offset of the effect due to lack of time was small. Therefore, when looking collectively at the risk of unmet medical needs, a statistically significant increase in risk was observed only for temporary agency workers.

Workers with unstable employment have low control over labor, find it difficult to claim their rights, and are excluded from social protection.19 South Korea is one of the few Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries that do not implement an injury and illness allowance system. Some standard workers can use paid leave provided by a company for 15–25 days annually, but several unstable workers, such as daily workers, special employees, and small business owners, have little paid leave. Therefore, unpaid leave should be used if workers need to be treated for illness or injury as an occasion arises.20 This means that unstable workers have to give up their daily earnings to use medical services; thus unstable workers who “live on a daily basis” delay or give up medical service use because they have to take the risk of unemployment and economic losses. As suggested by previous studies, medical insurance coverage has an important effect on the accessibility of medical services, especially among vulnerable groups.21 The medical system in South Korea is based on universal health coverage and compulsory medical insurance, but this can be an obstacle to receiving medical treatment because it has a personal copay for insurance services and a personal burden on noninsurance services.22 Inpatients pay 20% of the cost of covered services, but the cost-sharing of covered services ranges from 30% to 60% for outpatients.23 Given these points, high self-paying medical expenses inevitably act as a barrier to the use of medical services by unstable workers with a relatively low income. Therefore, medical insurance coverage should be strengthened to increase the accessibility of medical services for unstable workers. By lowering the personal burden when using medical services, unstable workers with low incomes would be able to use sufficient medical services and prevent unmet medical needs due to economic burdens.

However, the risk of unmet medical needs due to lack of time shows a different direction. This phenomenon is attributable to the relatively longer working hours of standard workers compared with nonstandard workers. In fact, the average total actual working hours (including overtime hours) is 179.8 h for standard workers, but it is 114 h for nonstandard workers, showing a difference of approximately 65.8 h per month in 2020.24 Because of this relatively long working hours, the probability of unmet medical needs due to lack of time is higher for standard workers than for nonstandard workers.

The OR of unmet medical needs in female temporary agency workers was lower than that among males. Gender differences observed in the current study are similar to those in a previous study.9 Women may have a smaller effect size than men because they are forced to drop out of the labor market more easily when working conditions become unfavorable, as suggested by previous studies.25 Under these conditions, the possibility of a selection bias should be considered. Moreover, female workers are more frequently exposed to second household duties than male workers in Korea. Therefore, female workers with standard working contracts may have more unmet medical needs due to housework than male workers, leading to the attenuation of the OR in our study.

This study presents empirical evidence of unstable workers’ compromised accessibility to medical services in Korea. In previous studies, employment instability was classified as one, but this study considers the multifaceted properties of nonstandard employment using the definition proposed by the ILO. The main strength of this study is that it is a representative population-based prospective study. Our panel data analysis follows the same individual who collects comprehensive health-related data over 8 years. This allowed us to focus on within-person changes in the experience of unmet medical needs as employment status changed while controlling for unobserved time-invariant characteristics. Failure to control for time-invariant individual characteristics can bias the estimation of results if there are correlations between observed covariates and unobserved factors. This is in marked contrast to the majority of previous studies, which are mostly based on cross-sectional data in this area.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, the experience of unmet medical needs can be considered subjective because they were defined using the respondents’ self-reported answers. However, in several situations, subjective unmet medical needs are as important as clinical evaluations because individuals usually perceive their own medical needs better than health professionals do. Studies using subjective and objective methods have tended to show consistent results.26 As a result, subjective unmet medical needs are the most common measure used in public health studies27 and were therefore considered appropriate for this study. Second, although the severity of the disease may affect the accessibility of medical services, the severity of the disease when using medical care was not included as a variable in this study’s model owing to a lack of information. In addition, this study could not sufficiently consider occupational factors, such as the health management system in the company and job control in the workplace, which might affect the association between employment status and unmet medical needs. Third, these results were obtained from South Korea, limiting the generalisability of our findings to other populations with different medical systems and cultural backgrounds that influence the level of unmet medical needs. Therefore, our results should be carefully considered when generalizing them to other countries.

CONCLUSION

This study found that temporary agency workers in the general Korean population have a significantly higher risk of unmet medical needs. They may be one of the most vulnerable groups in society with unmet medical needs and who are at exceptionally high risk. Access to healthcare services is a key social determinant of health, employment, and working conditions, and healthcare system-level factors should be considered to improve healthcare access. For example, nonstandard workers’ wages need to be increased to a level similar to that of standard workers if the nature of the work and contribution to production are similar, such as raising the minimum wage. Moreover, the government should implement a universal sick allowance system for all workers to prevent unmet medical needs for economic reasons.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mo-Yeol Kang and Joonho Ahn conceived and designed the study. Joonho Ahn analyzed the data. All authors were involved in interpreting the results and discussion. Joonho Ahn and Mo-Yeol Kang drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed, approved, and agreed to submit the final version of the manuscript for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to express appreciation to the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) because of its offering the raw data of the Korea Health Panel Study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022R1F1A1066498).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Korea Health Panel data are available at https://www.khp.re.kr:444/eng/main.do.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was exempted from The Catholic University of Korea Catholic Medical Center, Seoul Saint Mary’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (Board Exemption Number: KC22ZISI0348) because this study used secondary data, excluding confidential information.