-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Wayne R Lawrence, Neal D Freedman, Jennifer K McGee-Avila, Lee Mason, Yingxi Chen, Aldenise P Ewing, Meredith S Shiels, Severe housing cost burden and premature mortality from cancer, JNCI Cancer Spectrum, Volume 8, Issue 3, June 2024, pkae011, https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkae011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Unaffordable housing has been associated with poor health. We investigated the relationship between severe housing cost burden and premature cancer mortality (death before 65 years of age) overall and by Medicaid expansion status. County-level severe housing cost burden was measured by the percentage of households that spend 50% or more of their income on housing. States were classified on the basis of Medicaid expansion status (expanded, late-expanded, nonexpanded). Mortality-adjusted rate ratios were estimated by cancer type across severe housing cost burden quintiles. Compared with the lowest quintile of severe housing cost burden, counties in the highest quintile had a 5% greater cancer mortality rate (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.05, 95% confidence interval = 1.01 to 1.08). Within each severe housing cost burden quintile, cancer mortality rates were greater in states that did not expand Medicaid, though this association was significant only in the fourth quintile (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.08, 95% confidence interval = 1.03 to 1.13). Our findings demonstrate that counties with greater severe housing cost burden had higher premature cancer death rates, and rates are potentially greater in non–Medicaid-expanded states than Medicaid-expanded states.

In the United States, housing costs have increased at a faster pace than median income, disproportionally affecting low-income households (1-3). Nationwide, more than 10% of households are considered to have severe housing cost burden, meaning that they spend at least half of their income on housing (2). The unprecedented growth of the population experiencing unaffordable housing is a major public health concern as prior studies have linked this to lower health-care utilization, a greater numbers of emergency department visits, and worsening overall health (1,4). This situation is potentially attributed to the cost-cutting trade-offs between medical care and housing needs among those spending a large proportion of their income on housing.

Prior studies have suggested that Medicaid expansion mitigates financial strain by reducing the cost of medical care and increasing access to preventive care and in this way may influence cancer mortality (5-8). In Medicaid-expanded states, prior studies have suggested that cancers are more likely to be diagnosed at earlier stages, that patients with cancer have longer survival, and that a lower proportion of the population experience financial toxicity (5-7,9). The impact of Medicaid expansion and severe housing cost burden, however, on premature mortality from cancer remains poorly understood.

In this ecological study, we investigated nationally the association of severe housing cost burden with premature mortality from cancer across US counties and whether this association differs by state Medicaid expansion status. We further examined the association between Medicaid expansion status and premature cancer mortality by severe housing cost burden quintile.

Demographic characteristics and mortality rates for all cancers combined and cancer sites with the highest death rates were ascertained from national death certificate data from the National Center for Health Statistics from January 2016 to December 2020 (Supplementary Table 1, available online) (10,11). Our analyses were restricted to people aged 25 to 64 years to focus on premature death from cancer. The National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board waived approval and informed consent because the study used publicly available, deidentified data.

Our measure of county-level severe housing cost burden, obtained from the 2016-2020 American Community Survey, consisted of the percentage of households that spent 50% or more of their household income on housing (12). Severe housing cost burden was categorized by quintile (1 = lowest, 5 = highest), where higher quintiles included counties with a larger percentage of the population that experienced severe housing cost burden.

The county-level percentage of the non-White population was obtained from the 2020 American Community Survey. County-level median gross rent and the percentage of the population below 150% of the federal poverty level was calculated from the American Community Survey. The percentage of the population below 150% of the federal poverty level was based on the ratio of income to poverty level in the past 12 months. County metropolitan status was based on the Rural-Urban Continuum Codes developed by the US Department of Agriculture and grouped as nonmetropolitan counties and metropolitan counties (13). We further categorized states according to their Medicaid expansion status. Medicaid-expanded states were defined as states that implemented the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion on or before January 1, 2014 (25 states) (Supplementary Table 2, available online). Late expansion states were defined as states that expanded Medicaid between January 2, 2014, and December 31, 2020 (12 states). Remaining states were defined as non–Medicaid expanded (14 states).

Age-adjusted cancer death rates by severe housing cost burden were calculated. All rates were age standardized in 5-year age groups to the 2000 US population. Age-standardized death rates from 2016 to 2020 were used to compare cancer death rates by cancer site. Additionally, we calculated mortality-adjusted rate ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of each quintile group compared with the first quintile group, with multilevel linear mixed modeling clustered at the state level, weighted by county population, and adjusted for county demographic characteristics. We further calculated mortality-adjusted rate ratios comparing non–Medicaid-expanded states to Medicaid-expanded states (referent) by severe housing cost burden quintile. P for trend was calculated by modeling severe housing cost burden quintiles as a continuous variable. Regression analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), and statistical significance was set at a P value less than .05.

A total of 3123 counties with reported cancer deaths were categorized into severe housing cost burden quintiles. Larger concentrations of severe housing cost burden were clustered in more metropolitan counties, and premature cancer mortality rates were clustered in the Appalachian and southern region (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Age-adjusted premature mortality rates from all cancers combined were 88.1, 93.6, 96.6, 95.2, and 92.1 per 100 000 population for the first to the fifth severe housing cost burden quintile (P < .001 for trend) (Supplementary Figure 2, available online).

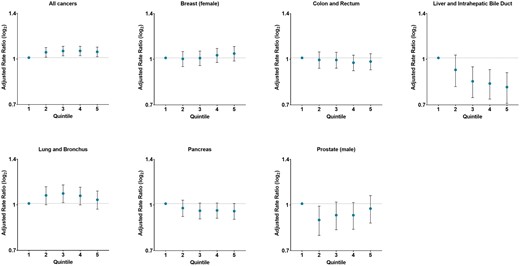

Compared with counties in the lowest severe housing cost burden quintile, counties in the highest quintile had a 5% higher overall cancer mortality rate (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.08; P = .02 for trend) (Figure 1). Similar results were observed for breast cancer, though results were not statistically significant (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.98 to 1.09; P = .02 for trend). Additionally, the adjusted rate ratio for liver cancer was 20% lower for the highest severe housing core burden quintile compared with the lowest quintile (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.71 to 0.89; P < .001 for trend). No clear patterns were observed for the other cancer sites. In analysis by state Medicaid expansion status, there were largely no differences in results, though compared with the first quintile, rates were higher for all other severe housing cost burden quintiles, though most confidence intervals overlapped the null (Supplementary Table 3, available online).

Adjusted premature cancer mortality rate ratios by quintile of severe housing cost burden and cancer site in US counties, 2016-2020. Adjusted for metropolitan status, proportion 150% below the federal poverty level, proportion of the population with non-Hispanic White race alone, and median gross rent. Note that the first quintile was used as the reference group. As quintiles increase, so does the percentage county households with severe housing cost burden.

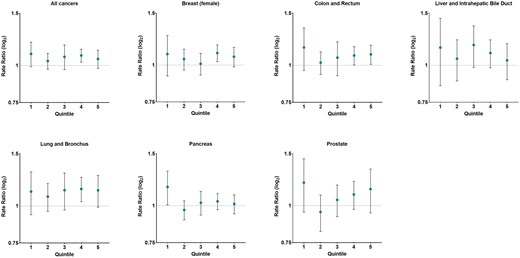

Within each quintile, cancer mortality rates were greater in states that did not expand Medicaid, though this association was significant only in the fourth quintile (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.13) (Figure 2). Similar results were observed for breast cancer and lung cancer, where rates were 10% (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.17) and 14% (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.25) higher for the fourth severe housing cost burden quintile among non–Medicaid-expanded states compared with expanded states. Additionally, compared with Medicaid-expanded states, the highest colorectal cancer mortality rates were observed in the fifth quintile (mortality-adjusted rate ratio = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.17) among nonexpanded states.

Adjusted premature cancer mortality rate ratios by quintile of severe housing cost burden and state Medicaid expansion status in US counties, 2016-2020. Adjusted for metropolitan status, proportion 150% below the federal poverty level, proportion of the population with non-Hispanic White race alone, and median gross rent. Note that Medicaid-expanded states were used as the reference group. Late Medicaid-expanded states were excluded. As quintiles increase so did the percentage of county households with severe housing cost burden.

In this analysis, counties in the highest quintile of people experiencing severe housing cost burden had higher premature mortality for all cancers combined. Additionally, though the association between severe housing cost burden and premature cancer mortality did not differ by Medicaid expansion status, the association between non–Medicaid-expansion status and premature cancer mortality for screen-detectable cancers was statistically significant elevated in counties with higher severe housing cost burden.

Interestingly, we observed that compared with the lowest severe housing cost burden quintile, there was an incremental decrease in premature mortality for liver cancer as the severe housing cost burden quintile increased. A potential explanation is that counties with a larger percentage of the population experiencing severe housing cost burden are largely in more urban, where accessibility to cancer specialists is greater.

Our findings suggest that counties experiencing severe housing cost burden would benefit from Medicaid expansion. Evidence from previous research has shown that compared with Medicaid-expanded states, nonexpanded states have disproportionately greater rate of hospital closure and patients with cancer experiencing financial toxicity, an independent predictor of cancer mortality (5,6,8,14). Consequently, individuals experiencing severe housing cost burden in non–Medicaid-expanded states are more likely to ration or postpone treatment and, among those in less urban areas, to travel further distance to receive cancer-related care (1,5-7). We observed that compared with Medicaid-expanded states, nonexpanded states had a greater risk of premature mortality from screen-detectable cancers (breast, colorectal, lung) among those in higher severe housing cost burden quintiles. Prior studies have documented that in Medicaid-expanded states, screen-detectable cancers are diagnosed at earlier stages than in nonexpanded states (5,6). Therefore, individuals experiencing severe housing cost burden in non–Medicaid-expanded states may be more likely to delay seeking evaluation when symptoms appear and have limited access to quality cancer care, thereby contributing to poorer outcomes.

The main limitation of this study was the inability to establish causality or the direction of association because of the study design. Severe housing cost burden is a broad measure of housing affordability and does not account for availability and quality of housing as well as other socioenvironmental contextual factors. Additionally, mortality rates were not adjusted for cancer risk factors (eg, cigarette smoking). Moreover, the ecological study design did not allow for causal inferences at the individual level.

In summary, premature mortality from all cancers combined was greater in counties with the highest percentage of households experiencing severe housing cost burden. Importantly, our findings showed that premature mortality from screen-detectable cancers were largely higher in non–Medicaid-expanded states in counties with a higher fraction of severe housing cost burden households. These findings illustrate that counties with high housing costs may benefit from Medicaid expansion, potentially reducing barriers in accessing quality cancer care. Future research is needed to confirm our findings using individual-level data to inform policy development centered on provision of affordable housing and expanding health-care coverage to all people.

Data availability

All data in this study are publicly available to researchers.

Author contributions

Wayne R. Lawrence, DrPH, MPH (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Neal D. Freedman, PhD (Data curation; Project administration; Supervision), Jennifer McGee-Avila, PhD (Data curation; Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Lee Mason, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Yingxi Chen, MD, PhD (Conceptualization; Data curation; Software; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Aldenise P. Ewing, PhD (Conceptualization; Resources; Validation; Writing—review & editing), Meredith S. Shiels, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute.

Conflicts of interest

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Role of the funder: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclaimer: The information presented by the authors are their own, and this material should not be interpreted as representing the official viewpoint of the US Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Cancer Institute.